27

Wheat and the “Millennium Drought” in Australia

2007

After seven lean years for Australia’s agricultural sector, a Millennium Drought drives the price of wheat internationally from record to record. Thousands of Australian farmers expect a total failure of their harvest. Is this a preview of the effects of global climate change?

“This is more typical of a 1 in a 1000-year drought, or possibly even drier, than it is of a 1 in a 100-year event.”

—David Dreverman, Head of the Murray-Darling Basin Authority

The Aboriginal term uamby means “where the waters meet,” except that on the Uamby farm, 50 kilometers northwest of the Australian wine-making and sheep-breeding city of Mudgee, no more water was flowing. The year 2006 was one of the hottest since weather records began on this continent and also one with the least rainfall.

Though the extreme drought had already affected the farm severely, it was only the beginning of the worst summer months—which fall between December and March in Australia. Water reserves were running low, and the animals could no longer find food. The pastures were bare and parched, necessitating purchases of water and food. Of the original 4,800 sheep on the farm, only 2,800 were left; the remainder had to be sold for 5 USD per animal, though the owners had expected about 40 USD.

The World’s Wheat

With an annual production of just under 600 million tons, various wheat varieties, together with corn and rice, are among the most widely cultivated cereals in the world. Wheat accounts for around one-fifth of the world’s calorie needs. It’s an important food for livestock and is also used to produce biofuels like ethanol. The average yield per hectare is just under 3 tons worldwide (1 hectare = 10,000 square meters, comparable to a soccer field). Large parts of the harvest are consumed by the producer countries themselves, so that only about 100 million tons of the total amount produced reach the world market—a factor that can affect price fluctuations in times of shortages.

More than 400,000 people were working in Australia’s agriculture sector, one of the country’s most important industries, and the situation was dire. At the beginning of 2007, due to the adverse circumstances, a farmer was taking his own life every four days. At the beginning of the next year, more than 70 percent of the agricultural land, about 320 million hectares, was affected by lack of rain and high temperatures.

The “granary” of Australia, the Murray-Darling Basin, produces 40 percent of the country’s wheat.

The situation was especially tense in the Murray-Darling Basin. The river system spans thousands of kilometers, an area about the size of France and Spain combined, supplying some 15 percent of Australia’s water. Officially, the rivers supplied around 50 percent less water in 2007 than the previous year, and 2006 itself had been a record low-water year. The basin is considered the granary of Australia, because this area alone grows 40 percent of the food on the continent. Meanwhile, small towns like Dimboola, about 330 kilometers from Melbourne, in the Australian wheat belt, were becoming ghost towns.

For the international market, Australia’s role as the second-largest exporter of wheat was of particular importance. In “normal” times, Australia exports 25 million tons every year. But normal times had not existed in Australia for seven years, making the drought the country’s longest. The year 2006 was the third-driest year since records began in 1900, and the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE) was estimating the 2006–2007 winter harvest at just 26 million metric tons, 36 percent less than the previous year. Even so, 2007 proved to be hotter, and experts began talking about a Millennium Drought. Australian prime minister John Howard declared it “the worst drought in living memory.” The direct cause was the phenomenon known as El Niño—a rise in Pacific Ocean temperature that affects weather patterns, and a phenomenon whose frequency and intensity has increased significantly through global climate change, according to environmental and weather experts.

El Niño Acts Up

El Niño (“the boy” in Spanish, referring to the Christ Child, since El Niño usually occurs around Christmastime) describes a weather phenomenon in which the sea surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific rises, wind systems over the Pacific change, and as a result, the cold Humboldt current west of South America weakens. A layer of warm water travels through the tropical East Pacific from Southeast Asia to South America, and water temperatures off Australia and Indonesia drop. The result is a change in global weather patterns: There are usually heavy rains on the South and North American West Coasts and drought, crop failures, and bush fires in Australia, India, and Southeast Asia.

In contrast, La Niña (“the girl”) is an exceptionally cold current in the equatorial Pacific, whose effects are excessive rain in Indonesia and drought in Peru.

The Australian harvest was crucial because the global 2006–2007 wheat harvest, at 598 million metric tons, was also significantly lower than the previous year’s 621 and 628 million tons. The 15 largest producing countries provided about 80 percent of that total. Australia, the second-largest exporter after the United States at the time, accounted for about 16 percent of global wheat exports.

The harvest came at a time of increasing demand, growing prosperity, and robust economic growth. For global wheat consumption, the forecast for this period was 611 million metric tons.

The collapse of Australian wheat production first hit Asia and the Middle East, since these countries traditionally imported grain from Australia. They were now looking for wheat in the United States and Canada. The Europeans were also affected by the heat. In Ukraine, the 2006 crop had shrunk by half.

In February 2008 the price for wheat more than tripled, compared to 2006, to almost 13 USD per bushel.

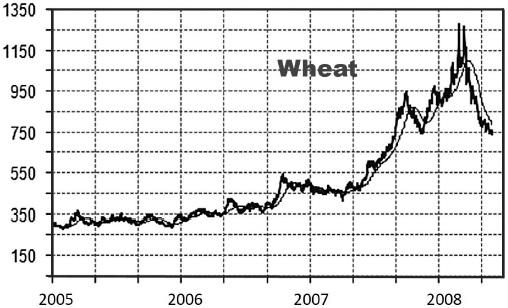

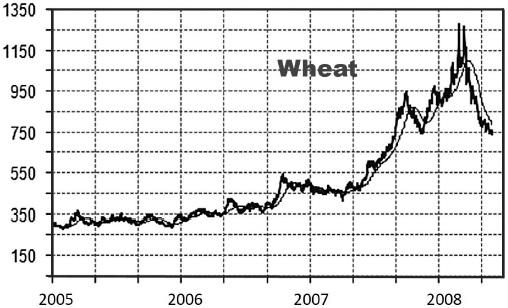

The price of wheat on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) soon began an unprecedented rally. The typical trading band for wheat in the years before 2006 was between 2.50 USD and 4 USD. At the beginning of 2004, however, inventories fell to their lowest levels since 1980. Bad harvests in Europe and China meant that the Middle Kingdom had to import wheat for the fourth year in a row. The price of grains was picking up dynamically.

In October 2006, wheat broke through the 5 USD mark for the first time and remained there. Then, in June 2007, wheat prices rose to 6 USD, climbed to 7 USD in August, 8 USD at the beginning of September, 9 USD at the end of that month, and rose to 9.50 USD at the beginning of October.

Meanwhile, global inventories continued to fall and reached a 26-year low. In addition, in Canada—another major wheat exporter on the world market—grain reserves plunged 29 percent year-on-year at the end of July, while Egypt, Jordan, Japan, and Iraq placed buying orders for large quantities of wheat.

Figure 24. Wheat prices in US cents/bushel, 2005–2008, Chicago Board of Trade. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

After this fast-paced rally, international wheat prices took a breather, but in hindsight that turned out to be just a short break. At the beginning of February 2008, wheat prices broke through the 10 USD barrier, and the price momentum continued. The closing price on February 27, 2008, was 12.80 USD, a dramatic tripling since early 2006!

The devastating drought had caused losses of around 50 percent in the recent Australian harvest. The situation began to relax slightly with the 2007–2008 harvest of 609 million tons, as the rapid increase in wheat prices had proved an incentive for many farmers to plant previously fallow land. A harvest of 688 million tons worldwide was estimated for 2008–2009. By then the unprecedented Australian drought finally had come to an end. However, weather experts painted a bleak picture for the country’s agriculture in the future.

Key Takeaways

•The year 2006 was the third driest in Australia since weather records started in 1900, but 2007 topped it. That year turned out to be the hottest year in history.

•After several lean years, the Millennium Drought caused devastating damages to Australian agriculture. The national wheat harvest dropped by 50 percent, and global grain markets panicked, since Australia was the biggest global exporter of wheat after the United States.

•In October 2006, wheat topped 5 USD for the first time. In summer 2007, the rally in wheat prices intensified. In February 2008, wheat prices broke the psychological barrier of 10 USD and closed the month at 12.80 USD. Prices had tripled since early 2006.

•The Millennium Drought in Australia was caused by El Niño, a weather phenomenon whose strength and frequency could be directly linked to global climate change, according to environmental and weather experts.