32

Crude Oil: Contango in Texas

2009

The price of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil collapses, unsettling commodity traders around the world. A 10,000-person community in Oklahoma becomes the center of world attention. The concept of “super-contango” is born, and investment banks enter the tanker business.

“Super-Contango is a state in which a forward price of a commodity is higher than the spot price to a greater extent than can be explained by the interest and storage costs that explain the usual state of contango.”

—Moneyterms.co.uk

Cushing is a small town in Oklahoma with fewer than 10,000 residents: There’s a Wal-Mart, some fast-food restaurants, and a few gas stations. Only massive tanks, pipes, and refineries hint that the town is somehow special. In the south of the city is a complex for the strategic oil reserves of the United States, with a capacity of 35 million barrels—one of the largest in the country.

Suddenly, at the beginning of 2009, Cushing—the only delivery location for West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the US benchmark for crude oil—became the focus of the world’s attention. In the oil market, big-time inventory building had begun. And it began on a large scale.

Trading in Crude

Because of the many different types and qualities of crude oil, market participants have agreed to trade in a few local varieties for reference: At the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), this is US West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil, at the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) in London it’s North Sea Brent, and in Singapore the Asian reference is Tapis. Additionally, there is an OPEC basket price, which calculates the average price of seven different types of crude: Sahara Blend (Algeria), Minas (Indonesia), Bonny Light (Nigeria), Arab Light (Saudi Arabia), Dubai (United Arab Emirates), Tia Juana Light (Venezuela), and Isthmus (Mexico). On commodity futures markets, WTI and Brent are the primary references for the price of oil, which is traded in 1,000 barrels per contract under the abbreviations CL (WTI) and CO (Brent) as well as the corresponding contract months (e.g., Z9 for December 2019).

In the wake of the financial market crisis and the deteriorating economic outlook, the price of crude oil had come under massive pressure in the second half of 2008. That summer, crude oil had briefly traded at more than 145 USD for a short time. But then, the price dropped to less than 45 USD. The withdrawal of investment capital (“deleveraging”) also contributed significantly to the price decline. This became obvious through an analysis of the short-term crude oil contracts in which financial investors are typically invested, and which were now much more affected than long-term contracts.

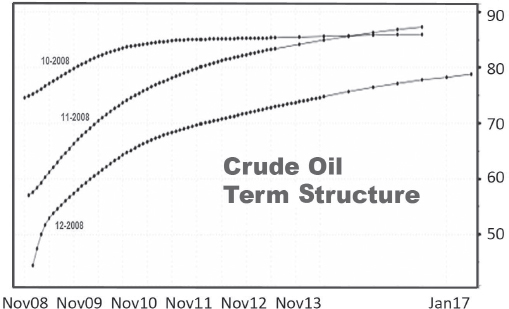

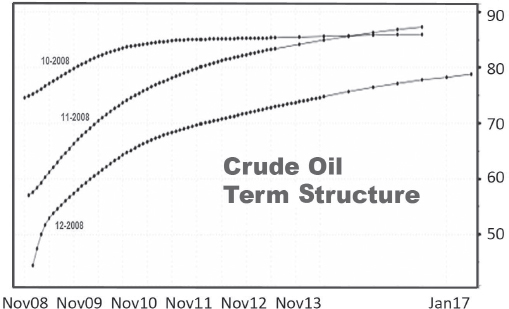

Figure 29. Crude Oil (WTI) Term Structure in USD/barrel, 2008. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

The forward term structure, which tracks the price of future crude oil deliveries over a period of several years, was still nearly flat in summer 2008, but from there, the contango structure of crude oil (WTI) increased. Contango refers to the situation in which spot prices are below the level of futures prices. This could be due to warehousing costs, including insurance and interest, for example, although those can be superseded by the effects of supply and demand.

Between October and December 2008, the contango became extreme. The price decline at the short end of WTI contracts led to a record price difference (the spread)—in excess of 20 USD—between contracts for WTI January 2009 and WTI December 2009. Commodity traders introduced the term “super-contango” to describe what was happening, and commodity analysts called the price distortion of crude oil “absurd.” WTI decoupled completely from other crude oil reference prices such as Brent and, as a barometer for international crude oil markets, was “as useful as a chocolate oven glove,” noted a commodity analyst of Barclays, the British investment bank. What led to this situation? And, more importantly, what were the implications?

Super-contango! Front-end WTI traded as low as 35 USD, while later crude contracts with later dates stayed above 50 USD.

The world’s attention turned to Cushing, the world’s “pipeline crossroads” and the only source of WTI crude oil. Contango favors stockpiling, because instead of a low current price, oil can be sold for more at a later date. The only obstacle is that the owner of the crude needs to have appropriate storage facilities. At Cushing, due to the increasing contango, the storage level of oil was steadily increasing.

Figure 30. Price spread of crude oil January (CLF9) and December 2009 (CLZ9) in USD/barrel. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

In January, oil inventories counted more than 33 million barrels (1 barrel equals 159 liters), and the remaining capacity literally was disappearing like ice in sunshine. The super-contango led to “super-storage,” because every holder of crude oil futures without the appropriate capacity had to sell crude oil, if needed, regardless of price. At its low, US crude oil was trading below 35 USD.

It’s hard to know whether the super-contango was merely an expression of the short-term oversupply of the crude oil market due to the economic slowdown, or whether this was the effect of disinvestment of index and hedge fund capital in the forward contracts. In any case, the steepness of the crude oil forward curve continued to increase.

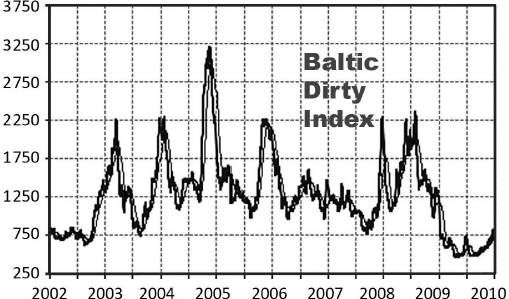

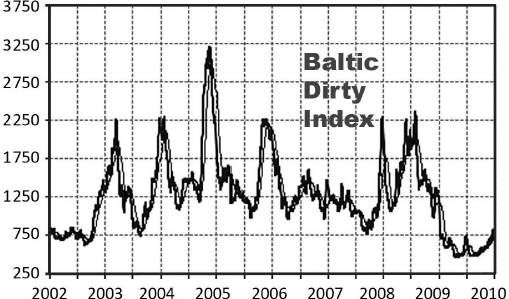

Figure 31. Baltic Dirty Tanker Index, 2002–2010. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

An additional factor, apart from the price differences, distinguished this situation from past events: The economic slowdown and the effects of the credit crunch had put international freight rates under extreme pressure. At the beginning of 2009, freight rates for oil tankers were around 85 percent below their highs in summer 2008.

The crude oil super-contango, combined with low freight rates, provided a lucrative business for investment banks.

For a short while early in 2009, the price difference between a current crude oil contract and a December 2009 contract exceeded 30 percent. The combination of super-contango and the low crude oil tanker freight rates opened up a new field not only for crude oil traders but also for investment banks, since it was possible to store crude oil in oil tankers on the high seas.

With sufficient inventories, it made no sense to sell oil at prices below 40 USD, if you could sell above 55 USD risk-free through a futures contract. January crude oil prices were trading 20 USD below December contracts, while the cost of storage aboard on a supertanker in January 2009 averaged around 90 US cents a barrel. Assuming that transportation, insurance, and financing were secured, there was an opportunity for immense profit for oil companies and traders.

Tanker Talk

The Baltic Exchange is a global marketplace for shipbrokers, shipowners, and charterers. The various indices of the stock exchange offer an important overview of freight rates differentiated according to cargo types, ship sizes, and shipping routes. The Baltic Clean Tanker Index tracks tankers carrying clean cargo, such as oil products (petrol, diesel, fuel oil, or kerosene); the Baltic Dirty Tanker Index is for tankers that carry cargo such as crude oil. In 2009, freight rates for bulk carriers—summarized in the Baltic Dry Index—had fallen by 94 percent since the previous summer, due to the economic slowdown and the credit crunch during the international financial crisis. In comparison, the freight rates for tankers lost a little less. Freight rates for crude oil fell by around 85 percent.

Tanker lease periods between three and nine months were particularly sought after.

In February 2009, Frontline, the world’s largest owner of supertankers, reported that 25 tankers had been chartered, and there were still open inquiries about 10 more ships. Any tanker that held less than 2 million barrels of oil was not statistically recorded, but industry experts estimated that there were as many as 80 million barrels on the water at the time, more than twice as much oil as was in official storage in Cushing. The profitable business had also taken on a new dimension. The new customers were no longer BP or Exxon, but Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Citibank, Barclays, and Deutsche Bank.

Ship brokers around the globe were surprised by the extent of storage inquiries. After all, 35 supertankers accounted for roughly 10 percent of crude oil tanker capacity worldwide. Due to additional demand, tanker freight rates recovered slightly from their lows. However, the floating inventories prevented a significant spike in oil prices during the year, despite any improvement in underlying economic data. After a nearly 75 percent drop in crude oil prices in just one year, the supply surplus of floating stock unsettled the market. For 2008, the International Energy Agency (IEA) reported a decline in oil demand for the first time since 1983.

Key Takeaways

•Cushing, a small town in Oklahoma, is the pipeline capital of the world—the only delivery point for WTI, the most important benchmark for crude oil.

•In the summer of 2008, crude oil was trading above 145 USD. But then the price collapsed to less than 45 USD, and WTI switched from backwardation into a deep contango. A super-contango was born.

•In combination with low freight rates due to the economic crisis, the oil super-contango provided a lucrative business for investment banks, which could physically buy oil, store it in supertankers, and sell it on futures exchanges, locking in a secure profit.

•The super-contango led to a massive supply glut in crude oil for a number of years.