35

Copper: King of the Congo

2010

The copper belt of the Congo is rich in natural resources, but countless despots have looted the land. Now Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC) is reaching out to Africa, and oligarchs from Kazakhstan aren’t shy about dealing with shady businessmen or the corrupt regime of President Joseph Kabila.

“The West exploited Africa and now it wants to save it. We have been living with this hypocrisy for too long. Africa can only be saved by Africans.”

—Joseph Kabila, President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

“We bought an asset from the Democratic Republic of Congo that was for sale.”

—Sir Richard Sykes, ENRC

On Friday, August 20, 2010, investors in the city of London listened closely as Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC), a 12 billion USD, London-listed Kazakh mining company, took over the majority stake in Camrose Resources, which held the Kolwezi mining licenses recently expropriated by the government of the Congo. The previous owner of the extremely lucrative licenses? The Canadian mining company First Quantum Minerals. This was explosive news!

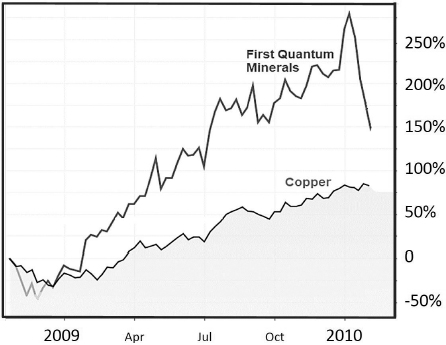

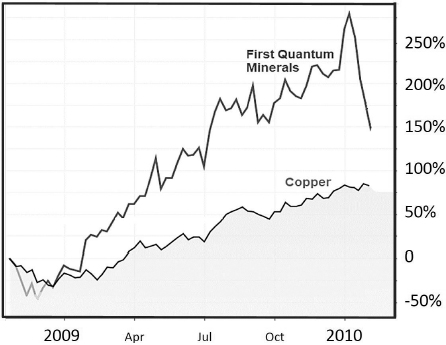

All of a sudden, after decades of colonialism, dictatorship, and warfare, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) was once again the focus of media attention and the international mining industry. The Congo, one of the poorest countries in the world, nevertheless has an immense wealth of natural resources. The African copper belt stretches from the Congolese mining province of Katanga to northern Zambia. Here lies around 10 percent of the world’s copper reserves. And in 2010, copper was scarcer and more expensive than ever before: Based on its 52-week low, the price of the metal had increased that year alone by 50 percent. For the first time, copper traded above 9,000 USD per metric ton on the London Metal Exchange (LME).

An Introduction to the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly Zaire, is the third-largest country in Africa, after Sudan and Algeria. Neighboring countries—the (formerly French) Republic of the Congo, the Central African Republic, Sudan, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Tanzania, and Angola—are all much smaller. With its wealth of natural resources, such as cobalt, diamonds, copper, gold, and other rare minerals, the Congo is a prime example of the “resource curse” thesis: The 70 million inhabitants of the Democratic Republic of the Congo are among the world’s poorest. Only Zimbabwe has a lower per capita GDP.

The Congo, whose capital is Kinshasa, gained independence from Belgium in 1960 under President Kasavubu and the popular Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. A period of instability and military intervention followed, beginning in 1965, under the long dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko, during which Mobutu and the elite of the country (now called Zaire) systematically looted the wealth of the nation.

The system collapsed in 1997, when Mobutu was ousted by Laurent-Désiré Kabila. In January 2001, L.-D. Kabila was murdered by one of his bodyguards under unclear circumstances, and the presidency passed to his son, Joseph Kabila. The latter stayed in power until the end of 2018. In January 2019, opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi was declared the fifth president of Congo-Kinshasa since its independence of Belgian colonial supremacy.

Despite the official end of the second Congo war in July 2003 (the first took place in 1997–1998), conflicts still persisted in the country up until today. In the course of this “African World War,” which involved eight African states and 25 armed groups, more than 5 million people died. It was the bloodiest armed conflict since World War II.

The Kamoto Mine near the town of Kolwezi is in the heart of the Congo’s mining district, where more than 3 million tons of copper and more than 300,000 tons of cobalt are believed to be in the ground. The current market value of copper reserves alone exceeds 30 billion USD. When the mine was still in operation, the machines of state-owned mining company Gécamines, once the largest company in Africa, moved about 10,000 tons of rock each day. In September 1990, however, the central part of the mine collapsed, burying many miners. The operation came to a standstill. Under the Mobutu dictatorship, reinvestments were neglected, and the largest mines fell into decay. In the late 1990s, Gécamines sold most of its projects to international mining corporations.

Figure 34. Copper and share price of First Quantum Minerals, 2009–2010. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

Beginning in 2007, the Congolese government undertook a review of more than 60 foreign mining agreements in order to increase state involvement and ownership in the mining sector. Since then, the revision of mining licenses has created multiple sources of conflict.

The government was aiming for at least 35 percent government ownership in future mining projects. In addition, newer regulations called for a signing bonus of 1 percent of the project value, a 2.5 percent license fee on the gross income, and a stipulation that the mine would go into production within two years.

The value of the mineral reserves of the African copper belt between the DRC and Zambia exceeded the GDP of half the African continent.

In August 2009, after a 2½-year review by the government, Canadian First Quantum Minerals’ Kolwezi license was terminated. The government accused First Quantum of breaching the 2002 mining regulations, though First Quantum denied it. One of the contentious issues was the increase of the Gécamines’ share by 12.5 percent—for zero costs involved.

The situation for the Canadian company was precarious, since it had already invested more than 700 million USD in expanding Kolwezi. Moreover, after First Quantum couldn’t come to an agreement with the Kabila government, the Congolese Supreme Court also revoked the company’s licenses for the Frontier and Lonshi mines in favor of the state mining company Sodimico—another bitter blow to First Quantum.

Sly Foxes

The wealth of natural resources in the Katanga province of the Congo smoldered into a power struggle among the three craftiest businessmen on the continent: George Forrest, Billy Rautenbach, and Dan Gertler. Sixty-seven-year-old Forrest, head of the Forrest Group, had been born in the Congo and was the old man of the Congolese mining industry. In early 2004, a few months after the end of the war in the Congo, Forrest and Kinross Gold entered into a joint-venture agreement with the government over the Kamoto Copper Company (later Katanga Mining).

Rautenbach, founder of Wheels of Africa, the largest transport company in southern Africa, was a friend of Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe. He went after the jewel, Katanga Mining, through the British company Camec. However, after a short takeover battle, the Congolese government announced a review of those mining licenses, and Rautenbach took the hint. He pulled back in September 2007. Rautenbach had previously been the manager of Gécamines but was replaced by Forrest, which accounted for the hostility between the two men.

Meanwhile, Gertler was laughing on the sidelines. Just 30 years old, he closed a joint-venture contract with the government of the Congo in 2004 for the development of KOV (Kamoto-Oliveira Virgule, later the company Nikanor). KOV was the only mine in Katanga with more resources than Kamoto Copper Company. More than 6.7 million metric tons of copper and 650,000 tons of cobalt—twice as much as in Kamoto—were estimated to be in the ground. According to market prices in 2018, the value of these resources alone exceeds half the GDP of Africa.

During the takeover battle for Katanga, Gertler bought shares in that mine through Nikanor. Camec finally lost its bid at the beginning of 2008, and Nikanor and Katanga Mining merged. In addition to his financial resources, Gertler had excellent connections: He is the grandson of the founder of Israel’s diamond exchange, a friend of then-Israeli prime minister Ariel Sharon, and the same age as Congo president Joseph Kabila, whom he considered a close friend.

In January 2010 the newly established Highwinds Properties, owned by Dan Gertler, was awarded the Kolwezi license in a shady deal. A few months later came the bombshell. On August 20, 2010, ENRC confirmed that it had secured the licenses to Kolwezi through its 50.5 percent acquisition of Camrose Resources for 175 million USD. The company said it intended to cooperate with Cerida Global, another Dan Gertler–controlled company. With the acquisition of Camrose, ENRC was also committed to a 400 million USD loan for Highwinds and a loan guarantee of another 155 million USD for Cerida’s debts.

The Kazakh company ENRC aggressively expanded its business in Africa and was not shy about dealing with African despots like Joseph Kabila.

Camrose also offered a majority stake in its subsidiary Africo to ENRC, whose copper and cobalt projects were located near its Camec properties. This was of high strategic importance for the Kazakh company, since ENRC had acquired the Central African Mining and Exploration Company (Camec) for 955 million USD in 2009. This is where Dan Gertler came into play, as Camec was 35 percent owned by the Israeli investor, who quickly unified the three Kazakh oligarchs—Alexander Mashkevitch, Patokh Chodiev, and Alijan Ibragimov—who owned 40 percent of ENRC.

The deals between Camec and Camrose were important milestones for ENRC’s aggressive expansion policy in Africa, along with a 12 percent stake in Northam Platinum in South Africa that ENRC acquired in May 2010. Regardless of pending possible expropriations and a skeptical attitude by many institutional investors, only time would show whether ENRC would have a more favorable outcome in Congo than its Canadian rival, First Quantum.

Sometimes time flies. In November 2013, ENRC delisted its shares from the London stock exchange. The following April, an official investigation into bribery and sanction-busting began in England, and the founding partners decided to take the company private again. In February 2014, news spread that the company needed to sell all its international assets—including the copper mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo—to repay debts. President Kabila, however, stayed in power until the end of 2018.

In January 2019, the opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi was declared the fifth president of Congo-Kinshasa. Leader of the opposition, Martin Fayulu, complained that Kamila, despite officially stepping down from office, would with his associates most likely continue controlling the levers of powers. Presidential elections had been due for more than two years, but elections had been postponed several times despite forceful protests. Since the end of Belgian colonial supremacy in 1960, the country had never seen a peaceful transfer of power.

Key Takeaways

•The African copper belt that runs between the Congo and Zambia holds an incredible wealth of natural resources. In 2010 it became the focus of upheaval when President Kabila revoked the mining license of Canadian firm First Quantum Minerals.

•Copper was now big business, as copper prices traded at record highs of more than 9,000 USD per ton on the London Metal Exchange (LME).

•The Kazakh (but London-listed) resource company Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC) began to massively expand its footprint in Africa. The firm’s leaders were willing to deal with shady businessmen as well as with President Kabila’s corrupt regime.

•In a murky transaction involving Dan Gertler’s Highwinds Properties, the expropriated assets of First Quantum were sold to ENRC. International investors were shocked, and the company went private a couple of years later.