36

Crude Oil: Deep Water Horizon and the Spill

2010

Time is pressing in the Gulf of Mexico. After a blowout at the Deepwater Horizon oil rig, a catastrophe unfolds—the biggest spill of all time. About 780 million liters of crude oil flow into the sea. Within weeks BP loses half its stock-market value.

“This well did not want to be drilled . . . it just seemed like we were messing with Mother Nature.”

—Daniel Barron, survivor of the Deepwater Horizon disaster

“I would like my life back.”

—Tony Hayward, CEO of BP

Deepwater Horizon was one of the world’s most advanced deepwater rigs. Installed in 2001, it was 121 meters long, 78 meters wide, and 23 meters high and cost 350 million USD. In April 2010, the giant lay about 40 miles off the coast of Louisiana in the Gulf of Mexico. Since February, the platform had been busy in the Mississippi Canyon Block 252, drilling in the Macondo reservoir about 4,000 meters below sea level.

April 20, 2010, promised to be a successful day, because the drill hole identified as API Well No. 60-817-44169 was about to be completed. The well would be sealed and prepared for production by a production platform. Every day counted because platform operators like Transocean charged oil companies on a daily basis. And in this case, BP was already concerned because Deepwater Horizon had been behind schedule for 43 days. The delays had already cost the big oil company more than 20 million USD.

Twenty years after the Exxon Valdez oil spill, an even bigger environmental catastrophe was looming on the horizon.

The Exxon Valdez—A Past Catastrophe

Shortly after midnight on March 24, 1989, the most severe environmental disaster in the history of the United States occurred. The 300-meter-long oil tanker Exxon Valdez was on its way from the oil-loading station of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, in the port city of Valdez, Alaska, when it collided with Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound. The accident caused a spill of almost 40,000 tons of crude oil. Around 2,000 km of coastline were contaminated, and hundreds of thousands of fish, seabirds, and marine animals died. Captain Joseph Hazelwood was drunk in his room at the time of the accident, and third officer Gregory Cousins had the bridge.

Despite an extensive cleanup, the ecosystem remains severely disturbed three decades later.

That morning, four BP managers arrived by helicopter to monitor the completion of the drilling. Only a few hours before, experts from the oil services company Halliburton had cemented the drill hole closed, but employees of Schlumberger, who were about to test the cement seal, were sent back to shore by the BP managers before they had accomplished their task.

Deepwater Horizon drilled for black gold in the Gulf of Mexico on behalf of BP.

To accelerate completion of the work, BP urged rapid replacement of the drilling mud in the well with seawater to prepare for early production. This decision precipitated an argument between BP and the Transocean managers, who considered that step premature. Unlike seawater, drilling mud holds back rising gas and oil. However, the managers of BP prevailed, and the work began.

The decision would prove disastrous. The hole had a leak, and drilling mud and gas bubbles began to spill out. The cement plug also appeared to be leaking. Work continued into the night, until suddenly a sharp hiss of methane was heard and a fountain of mud shot out of the derrick, signaling a blowout.

As the methane ignited, a huge column of flame rose into the sky. Suddenly the entire derrick was on fire, and four workers on the drilling deck were dead.

The alarm sensors designed to warn of fire and a concentration of toxic or exploding gases had been turned off to keep workers from being disturbed by false alarms in the middle of the night. Now, below deck, it was chaos. Workers, some of them barely awake and dressed in little more than a life jacket, were jumping off the platform into the water, trying to save themselves. But with the Deepwater Horizon in flames, the oil on the water’s surface had caught fire as well. Chaos also reigned in the rig’s two lifeboats.

Around 11 pm, the Damon B. Bankston, an 80-meter-long supply ship, rescued the survivors. Eleven people had died in the explosion. Two days later, the oil platform sank in the Gulf of Mexico.

The demise of the platform marked the beginning of the biggest environmental disaster in the history of the United States, an event that would provide the plot for a Hollywood blockbuster movie, starring Mark Wahlberg, in 2016.

The Macondo drilling ended in disaster. In the largest oil spill in the United States, nearly 780 million liters of crude oil ran out, and the market value of BP fell by half.

When fire broke out on the deck of the Deepwater Horizon, engineer Christopher Pleasant pressed the emergency button for the blowout preventer (BOP), a series of shut-off valves mounted directly above the well bore to interrupt the flow of oil into it. Like huge pliers, the massive shear jaw of the BOP was supposed to cap and close the well in case of disaster. The automatic emergency system was activated, but nothing happened.

A commission of inquiry later found that the Deepwater Horizon blowout preventer was poorly maintained, the hydraulic system was leaking, and the safety instructions had not been properly maintained. In addition, the ring valve of the device had been damaged weeks before. Not only was the blowout preventer in poor condition, as early as September 2009, BP had reported almost 400 defects on the rig to Transocean. However, maintenance had been delayed, and more than 26 systems were in poor condition. There were even problems with the ballast system.

After the platform sank, an oil slick formed. Approximately 1.5 km by 8 km at first, it expanded to almost 10,000 square kilometers within a few days. Between 5 and 10 million liters of crude oil were flowing out every day, and Louisiana, Florida, Mississippi, and Alabama all declared a state of emergency. According to the US Department of the Interior’s Flow Rate Technical Group (FRTG), the amount of oil that flowed out every 8 to 10 days matched the total amount of oil from the Exxon Valdez disaster. BP estimated that there were around 7 billion liters of crude oil in the source. Thus, it would take another two to four years until the entire amount of oil had oozed into the sea.

Shortly after the platform sank, BP initiated two independently made side-to-side relief wells (called the “bottom-kill method”), but the drilling would have taken about three months. Meanwhile, the capture of the oil with the aid of large steel domes was failing.

The depth of the seabed—around 1,500 meters—complicated the work. At the end of May 2010, several attempts were made to plug the leak with mud and cement (the “top- kill method”), but they, too, were unsuccessful. In the middle of July, BP succeeded in significantly reducing the oil flow with a new sealing attachment—a temporary closure was successful. As a result, on August 6, the leak was finally sealed permanently using a modified variant of the top-kill method (“static-kill”)—pumping in liquid cement through side relief holes. On September 19, five months after the Deepwater Horizon sank, BP declared the well “officially dead.”

It took five months to seal the oil leak.

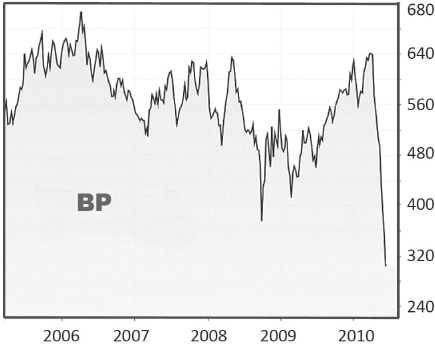

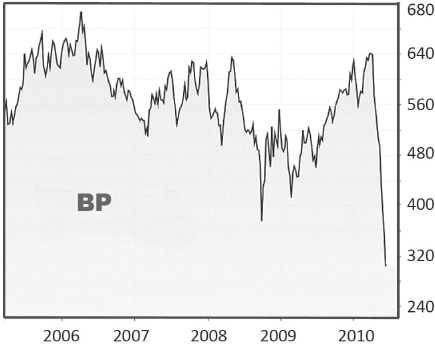

It was estimated that nearly 5 million barrels of oil, around 780 million liters, had run out, and BP’s stock-market value fell by half in the course of the disaster. The company announced that it would divest 10 billion USD worth of assets to defer the cost of the spill.

Figure 35. BP, share price fluctuation during first half of 2010. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

At that point only about 3 billion USD in costs had accumulated. But BP also set up a trust fund of more than 20 billion USD for the future consequences of the catastrophe. Still unanswered is the question of who bears the responsibility for the disaster. Undoubtedly, BP took high risks, applied non-industry-compliant practices to save costs, and, as the principal, bears the financial responsibility. Transocean’s role as operator of the oil platform also needs to be clarified, especially since the platform was in relatively poor condition. For Halliburton, the questions revolve around the doubtful completion of the cement seal of the well, and initial claims have also been made to BP’s partner companies Mitsui and Anadarko.

The disaster heightened public awareness of the risks associated with deepwater drilling, both in the Gulf of Mexico and in planned projects off Brazil and Africa. As a direct result of the catastrophe, the US government passed a deep-sea moratorium, temporarily banning all new deep-sea drillings. Although this was later repealed, no new licenses have been awarded. As a further consequence, President Barack Obama fired the head of the Minerals Management Service, Elizabeth Birnbaum. The agency, now renamed the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement, had grossly and negligently violated its oversight responsibilities.

It is impossible to estimate the economic consequences of the disaster, let alone the environmental consequences, which include not only the direct effects of the oil pollution but also the burning of oil and the use of toxic chemicals like Corexit, which have been used to combat the oil spill. BP said in 2018 that it would take a new charge over the Deepwater Horizon spill after again raising estimates for outstanding claims, lifting total costs to around 65 billion USD. The story of the disaster in the Gulf of Mexico will play out for decades in the future.

Key Takeaways

•At the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico, the Macondo drilling, at about 4,000 meters below sea level, ended in disaster. Nearly 780 million liters of crude oil ran out, and the market value of BP, the oil and gas company in charge, fell by half within weeks.

•The oil spill caused the biggest environmental catastrophe in the history of the United States, far more devastating than the oil spill of the Exxon Valdez 20 years earlier.

•As a consequence, US authorities temporarily froze all deepwater drilling licenses. BP is estimating a price tag of more than 65 billion USD.