39

Rare Earth Mania: Neodymium, Dysprosium, and Lanthanum

2011

China squeezes the supply of rare earths, and high-tech industries in the United States, Japan, and Europe ring the alarm bell. But the Chinese monopoly can’t be broken quickly. And the resulting sharp rise in rare earth prices lures investors from around the globe.

“The Middle East has oil. China has rare earths.”

—Deng Xiaoping, 1992

In 2013, geologist Don Bubar bought 4,000 hectares of land in the wilderness of Canada for less than half a million USD, hoping that in a few years the area would be worth billions. Bubar and his company, Avalon Resources, planned to develop a mine for rare earths and to start production by 2015. Gold fever had seized the mining industry. Almost 300 companies worldwide were exploring for rare earths and other exotic metals like lithium, indium, or gallium. Investors were happy to spend their money on these projects, because the supply of rare earths is limited, demand was high, and prices were soaring, reflected in press headlines almost every day.

Rare earths have become indispensable for modern high-tech applications—in computers, mobile phones, or flat screens, for example, and the growth of regenerative energy can’t be achieved without rare earths in electric/hybrid cars or in wind power plants. But these metals have been at the center of a trade conflict between the main producer, China, and the industrialized countries, a situation that has been worsening over the past few years.

What Are Rare Earths?

Rare earths consist of 17 metals: scandium, yttrium, and the lanthanides group of lanthanum, cerium, dysprosium, europium, erbium, gadolinium, holmium, lutetium, neodymium, praseodymium, promethium, samarium, terbium, thulium, and ytterbium. In most deposits, light rare earths (cerium, lanthanum, neodymium, and praseodymium) are found in large quantities, while the occurrence of heavy rare earths (yttrium, terbium, and dysprosium among others) is considerably lower.

One of the most extensively used metals is neodymium, which is indispensable for the production of permanent magnets, that is, magnets that do not discharge. Neodymium is used in mobile phones and computers, wind turbines, and electric/hybrid cars. Each megawatt of power from a wind generator requires between 600 and 1,000 kg of permanent magnets made of iron-boron-neodymium alloys. Moreover, in every wind turbine, there are several hundred kilos of neodymium and dysprosium.

Lanthanum is also used in many high-tech applications. For example, about one kg of neodymium is needed for the hybrid engine of a Toyota Prius, but the batteries contain about 15 kg of lanthanum. The German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources expects the demand for rare earths to rise to 200,000 metric tons a year. At current prices, this means a market size of 2 billion USD. Compared to other metal markets, such as that for copper, with an annual production volume of almost 20 million metric tons and a market value of almost 140 billion USD, rare earths are a tiny but profitable segment.

China has dictated world market prices of rare earths, since its production accounts for about 97 percent of the global volume of 120,000 tons per year. China also has almost 40 percent of the world’s reserves, while other significant reserves are located in Russia, the United States, Australia, and India.

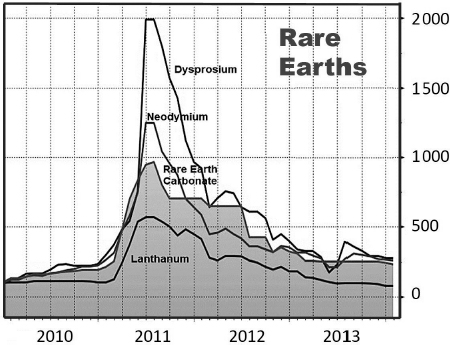

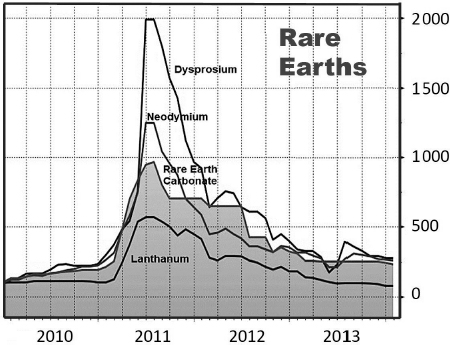

Similar to OPEC’s actions during the oil crises of the 1970s, China has been manipulating exports for years, and the United States, Japan, and Europe have all complained about export restrictions and high export duties. In 2005, exports were around 65,000 metric tons per year, but the volume has shrunk dramatically since then. As a result, prices for rare earths rose sharply from 2005 to 2008, and there was another price push in the third quarter of 2009. For the first half of 2011, the Chinese government announced exports of just 14,500 metric tons, and prices rose again. A kilogram of neodymium in May 2011 cost almost 300 USD, compared to just 40 USD 12 months earlier.

China also used its dominance in rare earth production as a political weapon. When Japan detained a Chinese ship captain, China banned rare earth exports to Japan in September 2010.

Figure 38. Rare earth carbonate, neodymium, dysprosium, and lanthanum, 2010–2013. Chinese onshore prices in RMB, indexed 30.12.2009=100. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

Over the past 20 years, industrialized nations have maneuvered themselves into this economic dependency. In the mid-1960s, the United States began producing rare earths in the Mountain Pass Mine, in the Mojave Desert of California. Until the late 1990s, this mine alone covered the world’s demand for these metals. Within the industry, this time period is known as the “Mountain Pass era.”

However, due to environmental constraints and low prices for rare earth metals, the mine closed in 2002. Since the beginning of the 1990s, the Chinese—able to produce the rare earths more cheaply and without worrying about environmental requirements—have begun to flood the world market.

The main Chinese production comes from Mongolia, where only a few kilometers away from the city of Baotou, with its multimillion population, is Bayan Obo, one of the world’s largest open-air mines.

It is estimated that up to 35 million metric tons of rare earths—more than half of total Chinese production—come from Bayan Obo. Another large segment of the Chinese supply derives from the southern provinces, where there are numerous small illegal projects in addition to official government mines. Production has its price, however. Processing rare earths generates large amounts of poisonous residues, which leads to heavy pollution by thorium, uranium, heavy metals, acids, and fluorides. Thus, untreated sewage has turned the nearby 12-kilometer-long drinking-water reservoir at Baotou into a waste dump enriched with chemicals and radioactive thorium.

Bayan Obo in China is the world’s largest mine for rare earth minerals.

Such heavy environmental damages are ironic, since these rare earths are indispensable to the clean energy industry, especially wind turbines and electric/hybrid cars. There’s no short-term, easy way out of the West’s self-inflicted scarcity. Development of an independent production capacity without environmental problems is a very capital-intensive undertaking. Exploration and exploitation of rare earth deposits is somewhat less problematic; despite their name, rare earths are not really scarce. Even the rarest metal in the group is around 200 times more common than gold.

Skyrocketing prices of rare earths have attracted many adventurers.

Skyrocketing prices in 2011 attracted investors and adventurers around the globe, as small mining companies began to search for rare earths and other exotic metals, and investors looked for attractive rare earth deposits to invest in. However, the majority of new rare earth deposits will never be developed or even have the slightest chance to go into production.

The two most promising companies were Molycorp and Lynas. Molycorp, which had an IPO in 2010, planned to reactivate the Mountain Pass Mine, while Lynas aimed to start production at the Mount Weld Mine in Australia in 2011. All other projects were looking at a planning horizon of at least five years. Meanwhile, the absence of a processing infrastructure was an even greater obstacle than the need for capital-intensive funding.

In 2015, Molycorp filed for bankruptcy after facing challenging competition and declining rare earth prices. The company was then reorganized as Neo Performance Materials. Lynas successfully got into production and made a first shipment of concentrate in November 2012. Today it operates a mining and concentration plant at Mount Weld and a refining facility in Kuantan, Malaysia. In September 2018, however, the processing facilities in Malaysia came under government review because of environmental concerns, and shares of Lynas began to tumble.

China will continue to be the dominant source of rare earths, which perfectly fits into the strategic plan issued by Chinese premier Li Keqiang and his cabinet in May 2015: Made in China 2025.

Key Takeaways

•The group of 17 rare earth metals, with exotic names like neodymium, dysprosium, or lanthanum, have become indispensable for modern high-tech applications like wind turbines and e-mobility.

•In 2011, China squeezed the supply of rare earths, using its dominance in rare earth production as a political weapon. Because its production accounts for more than 90 percent of global supply, China has been able to dictate world market prices.

•High-tech industries in the United States, Japan, and Europe sounded the alarm, but it was impossible to break the Chinese monopoly on the supply of rare earths in the short term. As a consequence, rare earth prices increased sharply, an average of 10 times between 2009 and 2011. Prices of neodymium and dysprosium, which are in the highest demand, increased even more drastically. This price spike attracted global investors who were eager to invest in rare earth deposits.