8

Soybeans: Hide and Seek in New Jersey

1963

Soybean oil fuels the US credit crisis of 1963. The attempt to corner the market for soybeans ends in chaos, drives many firms into bankruptcy, and causes a loss of 150 million USD (1.2 billion USD in today’s prices). Among the victims are American Express, Bank of America, and Chase Manhattan.

“You have caused terrific loss to many of your fellow Americans!”

US federal judge Reynier Wortendyke

At first glance, it seemed like a plot for a Hollywood movie: Workers deceived warehouse inspectors using oil tanks filled with water to hide one of the largest credit frauds in US history. It was all part of an attempt to corner the soybean market, a fragile house of cards whose collapse caused a loss of more than 150 million USD (the equivalent of about 1.2 billion USD today) and whose effects rippled throughout corporate America.

At the center of the debacle were Allied Crude Vegetable Oil, a New Jersey company, and its owner Anthony (“Tino”) De Angelis. In the end the unraveling of the scheme was analogous to the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in 2008: On a November evening in 1963, a group of employees of the Wall Street brokerage firm Ira Haupt & Co., including managing partner Morton Kamerman, sat in a conference room and spoke on the phone with Anthony De Angelis. As the conversation heated up, De Angelis accused Kamerman of ruining his company. Kamerman was not responsible for his firm’s commodity trading, but he was aware that De Angelis was one of his biggest customers. The Haupt & Co. partners were desperately looking for someone willing to buy soybean oil in large quantities, but they had no success. The next morning Kamerman understood a lot more about his company’s commodity business. However, the knowledge went hand in hand with the fact that Haupt & Co. was bankrupt due to the insolvency of Allied Crude.

Some Background About Soybeans

Soybeans, which are predominantly crushed for soybean oil and soybean meal, are produced and exported mainly by the United States “Corn Belt” (Illinois and Iowa), Brazil, and Argentina. Together these countries account for about 80 percent of the world’s soybean harvest of around 215 million metric tons. In most of the world’s production, the oil is extracted first, and the residual mass is used primarily as a feedstock. Soybeans, soybean meal, and soybean oil are traded on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) with the symbol S, SM, and BO and the respective contract month (for example, S F0 = Soybean January 2020).

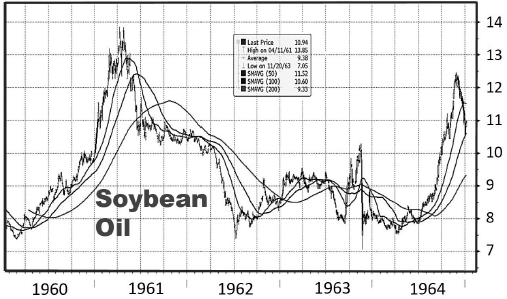

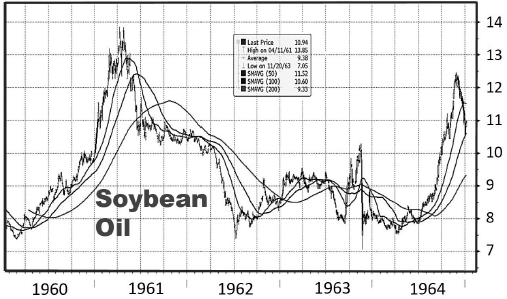

Figure 3. Prices for soybean oil, 1960 – 1964, in US cents/lb, Chicago Board of Trade. Data: Bloomberg, 2019.

Anthony De Angelis had founded Allied Crude Vegetable Oil in 1955 to buy subsidized soybeans from the government, process them for soybean oil, and sell the product abroad. Born in 1915, he was the son of Italian immigrants and grew up in the Bronx in New York. As a commodity trader, he dealt in cotton and soybeans, and between 1958 and 1962, he built a refinery in Bayonne, New Jersey, and leased 139 oil tanks, many as high as a five-story building. American Express Warehousing, a subsidiary of American Express, was paid by Allied Crude for storage, inspection, and certification of the oil volume. In 1962 De Angelis was responsible for about three-quarters of the total soybean and cottonseed oils in the United States. But in order to finance the rapid growth of the company in a highly competitive industry, he increased leverage by taking more and more credit, which was largely collateralized by the oil he produced.

And that is where the fraud began: Allied Crude Vegetable Oil never had as much oil as was necessary to secure its loans. A close investigation by American Express Warehousing would have revealed that De Angelis needed to store more oil than was available in the entire United States, according to the US Department of Agriculture’s monthly data. At its peak, De Angelis’s credit volume represented more than three times the amount of oil that could be stored in the tanks in Bayonne. But De Angelis was American Express’s largest customer. And his employees deceived the inspectors who were sent to check the collateral by pumping oil from tank to tank or filling the tanks mainly with water and only a small amount of oil. In this way the company continued to receive new credit lines.

Instead of expanding operations, however, the company used the credit lines for speculation in soybean futures at Chicago’s commodity exchange. De Angelis placed huge bets on rising prices for soybeans; he had to deposit only about 5 percent of the future purchase sum as a margin. Nevertheless, in his attempt to corner the entire market through further positions, De Angelis needed an even higher credit line.

He was already trading in futures contracts with Wall Street brokers Ira Haupt and J. R. Williston & Beane, and they agreed to further credit against stockpiles of the nonexistent oil. Both institutions were financed on the basis of their warrants by commercial banks Chase Manhattan and Continental Illinois.

By mid-1963, De Angelis had accumulated soybean positions equaling about 120 million USD or 1.2 billion pounds. A tick of only 1 US cent in the price of soybeans meant that De Angelis gained or lost 12 million USD. For a while his trades were profitable. In just six weeks in autumn 1963, the price of soybean oil climbed from 9.20 USD per pound to 10.30 USD. But on November 15 the market collapsed because of Russian plans to buy more US grain and the negative reaction to this. Allied Crude Vegetable Oil collapsed with it.

De Angelis deceived his creditors and caused losses of more than 1 billion USD in today’s prices.

Within four hours soybean oil had fallen to 7.60 USD per pound, and the Chicago Board of Trade called for additional margins from Ira Haupt, which the company was unable to provide because its main customer, De Angelis, was not in a position to do so. Even another 30 million USD borrowed by American and British banks was not enough to rescue Ira Haupt. Williston & Beane was also forced to merge with Walston & Co. because of dwindling equity.

The soybean market tumbled and took Allied Crude down with it.

Allied Crude went into bankruptcy, and as creditors reviewed the company’s tanks more carefully, they confirmed there were just 100 million pounds of soybean oil there instead of 1.8 billion pounds. This difference was worth about 130 million USD.

Affected by the debacle were banks, brokers, oil traders, and warehouses, huge firms like Bank of America, Chase Manhattan, Continental Illinois, Williston & Beane, Bunge Corp., and Harbor Tank Storage Co., to name just a few. The main loser was the parent company of American Express Warehousing: American Express faced legal suits by 43 companies, to the tune of more than 100 million USD. The share price of American Express dropped by more than 50 percent after the fraud hit the news. The scandal, however, received only limited attention, because two days later President Kennedy was shot in Dallas.

For Ira Haupt & Co., liabilities amounted to almost 40 million USD, which they were not able to meet, affecting more than 20,000 brokerage customers. Even worse than these financial claims was the damage to the reputation of the US economy. As for Anthony De Angelis, in 1965 he was sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment for fraud.

Key Takeaways

•In 1963 Anthony (“Tino”) De Angelis and his company Allied Crude Vegetable Oil were at the epicenter of one of the biggest corporate credit crises before the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

•By cheating on inventories and in a bold pattern of fraud, Allied Crude received immense credit lines for its business and heavily speculated on the rise of soybean and soybean oil futures in Chicago. Eventually the market for soybeans crashed in November 1963 and took Allied Crude Vegetable Oil with it.

•Affected by the fraud were several banks, brokers, oil traders, and warehouse companies, including prominent names like American Express, Bank of America, and Chase Manhattan.

•The huge scandal, however, was overshadowed by the assassination of President John F. Kennedy two days later.