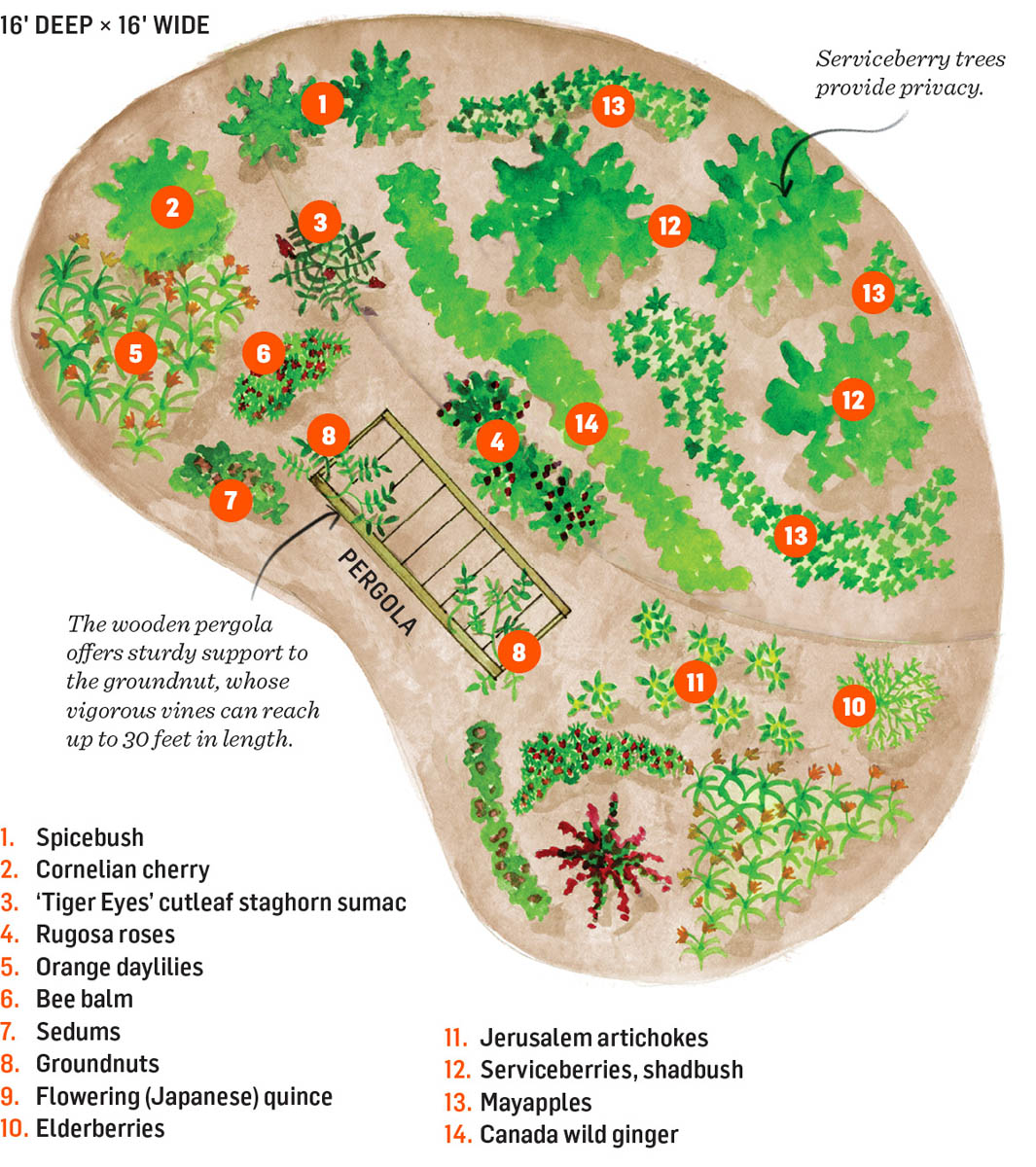

Ellen Zachos’s Forager’s Garden

A forager’s garden may seem rather contradictory, since foraging involves hunting for wild food plants, but Ellen Zachos points out that many forage-able plants also make excellent, low-maintenance garden plants. Her kidney-shaped bed combines native selections with nonnatives to make foraging at home a snap!

- Provides fruits, tubers, berries, and buds to forage on

- Uses low-maintenance and drought-tolerant plants

- The large, kidney-shaped bed is intensively planted and has a pergola for vigorous groundnuts

Foraging for wild edibles is becoming a popular pursuit for many who appreciate the range of edible plants found in the natural world. Those who don’t have the opportunity to forage in the wild, or who don’t live near desirable plant populations, can grow many of those delicious and unusual edibles in their gardens. Although not all of the plants included in Ellen’s design are native to North America, all have edible parts and make excellent garden plants. When foraging in the wild or selecting wild plants for your edible garden, there are two important considerations. First, if you’re not sure what plants or plant parts are edible, always refer to a comprehensive field guide or talk to an expert before you taste. Second, always obtain the permission of the landowner before you begin collecting.

Unique and delicious flavors. Ellen’s plan for a forager’s garden is based on the planting in her backyard, where she grows a range of wild plants, as well as cultivated varieties of wild plants, in a kidney-shaped garden. Her bed measures approximately 16 by 16 feet and is densely planted with trees, shrubs, and perennials grown for their fruits, flowers or buds, tubers, leaves, and stolons. “These are plants that I’ve enjoyed foraging for in the wild,” she notes. “They have unique tastes that are unlike anything you’ve ever tried before, and if they weren’t delicious, I wouldn’t grow them.”

Because half of Ellen’s garden is shaded by a neighbor’s large oak tree, she has tucked shade-tolerant plants at the back of the bed, leaving the sun lovers near the front. If shade isn’t an issue, this plan will also work in a full-sun location.

Protein-packed groundnut. The serviceberry trees at the back of the garden create a living privacy screen, blocking out undesirable views, while a sturdy wooden pergola at the front of the garden adds vertical interest and support for the vigorous growth of the groundnut, which can grow up to 20 feet long. This native legume was a staple in the diet of Native Americans, who enjoyed the tubers. Like potatoes, groundnut tubers are high in starch, but they’re also incredibly rich in protein, containing about three times as much protein as a regular potato.

While Ellen enjoys foraging for wild edibles, she doesn’t advocate digging up entire plants to bring them back to your kitchen or garden. All of the plants included in her plan are available at nurseries or through mail order. When foraging in the wild for edibles, Ellen offers some advice on harvesting. “A general rule among foragers,” she says, “is to take no more than a third of the crop, to leave some for wildlife and other foragers, and to allow the species to continue to propagate.”

Controlling Tubers

Left to their own devices, Jerusalem artichokes and groundnuts will take over the universe! To control their rampant growth, Ellen advises that about half to one-third of the tubers should be dug up each year in autumn and stored for eating. The rest can be left in the ground for future crops.

Low-maintenance plants. Growing perennial native or cultivated varieties of native plants is also a simple way to enjoy homegrown food with little work and ongoing maintenance. Ellen considers herself a “lazy, lazy gardener,” and she appreciates the drought tolerance and low grooming demands of these plants (no daily deadheading). Her native plant selections come together to form an attractive, low-maintenance, and productive garden that will support the local populations of bees, butterflies, and birds who rely on pollen and nectar from native plants for food.

Ellen’s Garden Plan

1. Spicebush (Lindera benzoin). Grown for its berries. Include 1 male and 1 female plant. “It’s hard to describe the taste of the berries in terms of other tastes; I find it somewhat peppery but also like it in desserts,” says Ellen. “Some people compare it to allspice, and it blends well with the wild ginger stolons in pies and rubs (for meat).”

2. Cornelian cherry. Grown for its fruit, this is not a true cherry but a relative of flowering dogwood. Only one is needed to produce fruit. Many varieties are “too tart for most people to enjoy plain,” but “this fruit has tons of pectin and makes an easy jelly,” notes Ellen.

3. ‘Tiger Eyes’ cutleaf staghorn sumac. Grown for its berries, ‘Tiger Eyes‘ is a better-behaved member of the sumac family, a species well known for vigorous suckering. If you’re worried about this small shrub becoming invasive, plant it in a container. Use the berries to make sumac lemonade or sumac-elderberry jelly.

4. Rugosa roses. Grown for their hips. “Rose hip soup!” laughs Ellen. Three plants are included here to make a nice clump.

5. Orange daylilies. Grown for their unopened buds and tubers. “Sauté the buds in olive oil and garlic — they’re better than green beans!” Ellen says. “The tubers can be roasted like potatoes.” Ellen also says that the young shoots and mature flower petals are edible, but she finds them less remarkable.

6. Bee balm. Grown for its flowers and leaves. Ellen notes that red-flowering cultivars lend eye-catching color to homemade vinegars and that the flowers and leaves of bee balm make excellent substitutes for oregano.

7. Sedums (a low-growing type such as Sedum cauticola [Hylotephium cauticola], S. rupestre, or S. sieboldii). Grown for their leaves. “Add a few leaves to your salad for a succulent crunch,” Ellen suggests.

8. Groundnuts (Apios americana). Grown for their tubers. Two of these plants are trained to trail over the pergola. “The taste is like a dry, nutty potato, and they can be roasted, boiled, or pan-fried,” says Ellen.

9. Flowering (Japanese) quince. Grown for its fruit. “The fruits are too hard and tart to eat plain, but they make an excellent jelly (lots of pectin),” she says. “I also love them for membrillo (a quince paste) and poached in red wine.”

10. Elderberries. Grown for their flowers and fruit. In the garden, Ellen prefers a black foliage cultivar, such as ‘Black Lace’, for its ornamental and edible qualities, using it to make elderflower “champagne” as well as elderberry jelly and wine. She notes that the black foliage cultivars are slightly less productive than their green-leafed counterparts.

11. Jerusalem artichokes. Grown for their tubers. “I like them best very thinly sliced raw in salads, but they’re also tasty baked, boiled, and pureed,” she says.

12. Serviceberries, shadbush. Grown for their berries. Ellen emphasizes that the berries should only be picked when fully ripe and dark purple in color. “If you harvest red or reddish blue fruit, you’ll be disappointed, since the fruit won’t be fully sweet,” she says.

13. Mayapples. Grown for their fruit. “All parts of the mayapple are poisonous except for the ripe fruit, which are yellow and slightly soft to the touch,” says Ellen. “You may read that unripe fruit can be harvested and allowed to ripen on the windowsill, but I don’t recommend it, as the superb, tropical flavor doesn’t fully develop this way.” She adds that if you must pick the fruit before they are fully ripe, make sure they are showing at least some sign of yellow because completely green fruit will never ripen to be delicious.

14. Canada wild ginger. Grown for its underground stolons. “I dig up several clumps in the fall, snip the stolons that connect the clumps, then replant the clumps,” says Ellen. “No harm done to the plants, and the stolons are an unusual and versatile spice.” Use them fresh or dried with apples, pears, and pork.