2

Roll the Dice

“Try everything and see what works” has long been the philosophy behind both Larry Page and Sergey Brin’s “hopeful monsters” strategy at Google and Richard Branson’s business experiments at Virgin. All three entrepreneurs illustrate a philosophy that could be called Darwinism, but, if so, that’s only one strand of it.

Take Google. As an Internet search company, it works at a fundamentally different pace from other industries. Web software changes continuously. You don’t plan it rigidly; you let it evolve day by day in response to customer behavior. The faster and more flexibly things evolve, the more successful your products will be. That’s the “hopeful” part.

The flip side with this approach, though, is that no one really knows where Google is going—or what its ultimate effects will be. Will Google destroy libraries, films, or books? That’s the “monster” part of random evolution. Add to which, there is indubitably another side of Google: a taste for killing things. Fortunately, so far, it’s mainly been the company’s own products! Even so, killing a product is usually considered a shameful thing for a business. It disappoints customers, and it looks like an admission of failure. So most companies downplay any change of plan as merely a change of emphasis or a readjustment. Google, however, does the exact opposite. It trumpets to the world that it’s terminating products. Turning off Google Reader or Google Desktop is an accomplishment to be proud of!

Michael Mace, author of the business strategies book Map the Future and former director of worldwide customer and competitive analysis at Apple, says that Google doesn’t seem to respond to the rules and logic used by the rest of the business world. It passes up what look like obvious opportunities, invests heavily in things that look like black holes, and proudly announces product cancelations that the rest of us would view as an embarrassment.

Yet, if Google is seen as a kind of ongoing autonomous experiment, the cancelations are just as exciting, and certainly as informative, as the successes. The downside with such try-outs, as Doctor Frankenstein found, is that they have a nasty habit of ending up in chaos, even dangerously out of control. We must hope that Page and Brin’s creation retains some memory of its mysteriously dismantled founding credo: don’t be evil.

Any talk of corporations conducting autonomous experiments brings to mind the highly successful entrepreneur Richard Branson. On the surface, he has little in common with the Google founders. Branson is from an earlier, groovier generation and started out in the music biz. Today, however, his companies, under the brand name Virgin, range from insurance to space flight. And for decades he has enthusiastically applied to his businesses the same spirit of “try everything and see what works” that permeates Silicon Valley start-ups.

Richard Branson is now a billionaire who lives on a tropical island, but I remember him starting out as a British hippy with a couple of grubby record shops, including one in my hometown of Brighton, busy making his name promoting trendy punk bands and selling vinyl records.

Where the Google founders are academic high-fliers who seem to relax by designing 3-D printers in Lego (no, really! Page did this), Branson is refreshingly populist. Not for him sweeping scientific theories like Darwinism. Instead, Branson claims to have been directly influenced by a cult 1971 classic called Dice Man by Luke Rhinehart—actually a pseudonym for George Powers Cockcroft, a reclusive figure who says that he admires Zen philosophies. Selling more than two million copies, the book offers a refreshingly subversive way to deal with the complexity of modern life: “let the dice decide.”

DICE MAN

AUTHOR: LUKE RHINEHART (AKA GEORGE POWERS COCKROFT)

PUBLISHED: 1971

Dice Man tells the story of a psychiatrist who, feeling bored and unfulfilled, begins making life decisions based on the casting of dice. He creates lists of six possible actions for himself and then “lets the roll of the dice decide.” The outcomes he gambles with are not sophisticated stuff, and along the way he breaks lots of taboos, including committing murder, breaking psychiatric patients out of hospitals, and causing all kinds of chaos. The novel became a cult classic for its subversive approach to life in general and antipsychiatry sentiments in particular. At the same time, due to its central message as well as its treatment of crime and sexuality, it was considered controversial. On its initial publication, the cover bore the confident strapline, “Few novels can change your life. This one will.”

The key point of the text—and it must be remembered it is only a fictional story and not really an alternative life strategy being presented—is that while some of the actions he lets the dice decide are merely whimsical and eccentric, others go against his own sense of morality, not to mention the law. At the end of the tale, Rhinehart is finally forced to choose between his promise to obey the dice and the rules of both society and his own conscience.

Many people have called the book out as dreadful, and mainstream reviewers shunned it. And yet, especially with outright criminality removed, the idea is intriguing. Indeed, the germ of the book came from a course Crockcroft led while teaching psychology at a US college. One class focused on freedom and the ideas of the philosophers Nietzsche and Sartre, and he challenged the students to consider whether the ultimate freedom was to get away from actions dictated by force of habit or simple causality and instead make all their decisions by casting dice. He was so struck by the response that he decided to write the book.

Older and wiser now, Cockcroft stresses the value of considering the range of possibilities that exist before each act (the roll of the dice requires you to think of only six possible outcomes), and he links his youthful folly to wider debates in business science where an element of chance is introduced to enhance creativity.

Tip: If you are tempted to try this, make sure none of the outcomes you consider are too rash or really outside the bounds of acceptability. Shouting out a snatch of song on the hour, as Branson already did, may already be on the very edge of tolerable!

The crux of the dice strategy is deciding how much power you give them. In the novel, Cockcroft actually allows the technique to decide such things as who to marry! As the book puts it, “Once you hand over your life to the dice, anything can happen.” In real life too, Branson has admitted openly that the book influenced his decision making, particularly in the early days of his Virgin Records label.

In an interview with the main British TV magazine, nostalgically called The Radio Times, Branson has said, “I was very much under the influence of the Dice Man books . . . It’s where you compile lists of actions and, after throwing the dice, have to adhere to whatever number you’ve placed by that particular instruction.”

By way of an example, Branson recalls what happened when he used the technique while on a trip from the UK to Finland to see a pop group called Wigwam just prior to the release of their LP. “I had made this list of things to do and threw the dice, which told me that for all that day I had to scream loudly on the hour every hour for twelve hours.” Yes, you read it right. Branson created some pretty weird options for himself.

“So there I am at the Wigwam gig and the band are playing not the loudest song in their set. I can see the hour coming up, thinking, you know, oh, please finish the song so my shriek can be lost in the applause.” According to a Press Association report, when Branson was asked if the crowd managed to drown out his screams, he admitted, “Not a hope. I had to just bellow it out. Dreadful for everyone, really. . . . I had to do it again during their encore.”

If this just sounds like a media personality trying to be a bit wacky, the reality of Branson’s life really has been to let randomness decide events. For example, he only came up with the name for his chart hits music series “Now That’s What I Call Music!” because he spotted a sign with those words in a bric-a-brac shop. What’s more, he was in the shop not to buy bric-a-brac (which would have been logical) but to woo the girl who worked there. She later became his wife. It seems that another lucky roll of the dice, metaphorical if not actual, came in 1992 when Branson’s business empire was creaking under the strain of maintaining his airline, Virgin Atlantic. He decided to sell off his profitable music industry operation, Virgin Records, to EMI to provide a cash lifeline, gambling his core asset on what looked like a risky new venture.

Branson goes further into the nature of this kind of gamble at length in his autobiography, The Virgin Way: Everything I Know about Leadership. He starts by stating that luck is one of the most misunderstood and underappreciated factors in life. He insists that luck is really about taking risks. “Those people and businesses that are generally considered fortunate or luckier than others are usually also the ones that are prepared to take the greatest risks and, by association, are also prepared to fall flat on their faces every so often.”

Today, Branson, as the founder of the Virgin Group, has an estimated net worth of $5 billion. But he surely took a risk when he dropped out of school (plus, it was a pretty posh school) at the age of fifteen to produce a magazine to campaign against the Vietnam War instead. No money in that, but it did lead to his first moneymaking scheme: Student magazine. He managed to get some big-name interviews but wasn’t focused on turning a profit.

After that, Branson pivoted into very different territory—music. He rolled the dice (metaphorically) and launched a mail-order record business. It started as a way to make the magazine pay, but it soon grew into the profitable music and entertainment business called Virgin Records. Hole in one!

Branson offers the example of a golfer doing this, saying that he once watched a golfer chip out of a deep greenside bunker in the final round of the British Open golf championship. The shot was too high, but the ball just clipped the top of the flagpole and dropped right into the hole. The TV commentator exclaimed, “Oh my goodness, what a lucky shot!”

According to Branson, the golfer was not so much lucky as he was reaping the rewards of thousands of hours spent practicing how to get a golf ball out of a bunker and onto the green. The shot illustrated the old saying “The harder I practice, the luckier I get.”

Certainly, over the years (like that golfer) Branson has often been accused of being lucky in business, but he insists that he’s entitled to some credit because “a lot of very hard work has played a major part in any luck that has come my way.” It does seem that sometimes he has just been fortunate, the early success of Virgin Records being the classic example. The company turned an almost immediate profit in the UK, but in the music business you need a presence in the United States to really succeed. Branson kept encountering closed doors there though. One time, he had a meeting with the legendary head of Atlantic Records, Ahmet Ertegun, during which he hoped to persuade him to take on Virgin’s first-ever album release, Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells. The record had already become a huge hit in the UK, but no one seemed very interested in the United States. Indeed, Ertegun insisted that an all-instrumental album like Tubular Bells would not sell in North America.

There was certainly nothing charmed about that meeting, but while Ertegun just happened to be playing the album in his office (and still trying to figure out what all the fuss in Britain was about) in walked movie director William Friedkin in search of some backing music for his new movie.

Even as Ertegun moved to turn the music off, Friedkin heard a snatch of Tubular Bells and instantly loved it. The result was that Branson got a US deal with Atlantic that included the use of his band’s music in one of the 1970s’ biggest blockbuster movies: The Exorcist. Thus Tubular Bells was introduced to a generation of young people and a global audience.

Now Branson says that you could call the success of Tubular Bells luck if you want, but he had worked hard at trying to win over Ertegun. Branson’s efforts were vital to getting the record into Ertegun’s office in the first place.

Or consider another time that Branson rolled the metaphorical dice that came when his flight from some Caribbean island to Puerto Rico was canceled. It seemed that he was going to miss an important meeting. Not willing to miss a rendezvous with a new female acquaintance, Branson simply found a chartered jet and put up a sign: “$29 per ticket.” He quickly sold out the plane’s other seats, made it to Puerto Rico, and discovered a taste for running an airline.

What do you do if you discover such a thing? (My ten-year-old has such a taste too.) Well, what Branson did was to ring up Boeing the next day and ask to borrow a plane with the option to return it if in a year things hadn’t worked out. It sounds like a pretty hopeful, not to say hopeless, approach, but here’s where it seems that luck once again came in. Although Branson didn’t know it, Boeing, in fact, had their own agenda in the UK, and it suited them to have a low-cost rival challenging British Airways’ then monopoly.

“I got lucky,” Branson writes. “Right place. Right time.”

Indeed, plans that work can seem like lucky guesses—like rolling the luck dice or spinning the roulette wheel—but Branson says that he has often covered so many options that he is bound to get lucky sometimes. No wonder he says his company slogan is “Screw it, just do it.” Branson runs hundreds of different businesses under the Virgin brand, and, of course, his approach has also brought its own share of wrong turns and miscalculations. Here are a few examples of failures where his luck seemed to desert him:

●Soft drinks. Remember Virgin Cola? The drink was too similar to “the real thing” to make any impact—Branson let it go to the wall.

●Motor sales. Hello and goodbye to Virgin Cars, intended to change the way cars were bought. It too sunk without a trace.

●Online music. Ditto for Virgin Digital, Branson’s attempt to rival Apple’s iTunes. It struggled and consumed a lot of cash before disappearing in 2007.

Actually, during the initial test flight of Virgin’s first and then only plane, Branson’s dice seemed unlucky as a flock of birds flew into the engine of the rented Boeing 747, causing extensive damage. The cost of repairs to jumbo jets is enormous; the company couldn’t borrow money for repairs without being certified, and the airline couldn’t get certified to start carrying passengers without a working plane!

Branson had to gamble the resources of his other companies to get the repairs done. But his airline got the certification it needed, and Virgin’s inaugural flight from Gatwick to Newark was a success. Mind you, when Branson, as the wealthy owner of Virgin Atlantic Airways, was asked how to become a millionaire, he had a quick answer: “There’s really nothing to it. Start as a billionaire and then buy an airline.”

A curious tale Branson told James Altucher during a podcast takes on the nature of chance. When Branson’s children were eighteen and twenty-one, he took them to a casino and gave them $200 each to play with. The point was not to give them a taste for gambling but rather to teach them, on the contrary, that gambling was a mug’s game and that the only way to make money in a casino is to be the owner. Sure enough, after half an hour they had lost all their money and went to have a reflective drink together. However, as they were doing this, a cheer went up from one of the gambling tables and someone came over and told them that one of their chips had actually just come up as a huge winner! Branson insisted his children didn’t misread the lesson though: he redistributed all the winning tokens to the other players and left the casino.

THE STRANGER

AUTHOR: ALBERT CAMUS

PUBLISHED: 1942

The French writer Albert Camus wrote a celebrated first novel called The Stranger (or sometimes The Outsider), which parallels Luke Rhinehart’s book in several ways. In his book, Camus too tries to reveal the absurd, random character of the universe by creating a character, Meursault, who (like Branson) has rather abruptly discontinued his education and is now working as a clerk with a shipping company. Meursault follows none of the normal assumptions about life and is without social ambition let alone belief in any religious or rational meaning in the universe. In Camus’s tale, a series of chance events leads Meursault to eventually commit murder and be condemned to death.

In real life, by contrast, Branson’s interest in randomness and challenging social conventions seems to have served him well. Or perhaps we might just say, the real-life Branson, like the Google founders, seems to have been fortunate in certain key rolls of the dice.

Mathematicians know that the outcomes of dice only appear to be random; over time they can be precisely computed. This was at the heart of Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin’s scientific approach to trying everything.

Take their core idea of making a new kind of Internet search engine based on the number of links Web pages have. This wasn’t originally arrived at as part of a business strategy but rather arose in a more happenstance, random way that both Darwin and Rhinehart would have liked. While a doctoral student at Stanford University in California, Page came up with multiple competing projects across various areas and then asked his supervisor, Terry Winograd, to help select a winner. More or less on the spur of the moment, Winograd said that the one described as something to do with the link structure of the Web “seems like a really good idea.”

From this small exchange, Page, along with his friend Brin, developed a search algorithm approach called PageRank. It was Brin who had the idea that information on the Web could be ordered in a hierarchy by link popularity. At its simplest, this means that a Web page is ranked higher the more links there are to it. Page and Brin were always aware, though, of the quality issue implied by the endless generation of new pages on the Web, usually effortlessly created without any editorial control or standards, or as Page put it in an early account, “The reason that PageRank is interesting is that there are many cases where simple citation counting does not correspond to our commonsense notion of importance.”

An academic paper (coauthored by Rajeev Motwani and Terry Winograd) described PageRank and also sketched out an initial prototype of the Google search engine. Shortly after, Google Inc., the company behind the search engine, was founded.

PAGERANK

An early step in the Google project was a paper entitled “The PageRank Citation Ranking: Bringing Order to the Web.” Published by Brin and Page in 1998, its solution to the problem of dodgy links and measuring quality on the Web is set out, dautingly, like this: “Let A be a square matrix with the rows and columns corresponding to web pages. Let Au;v =1/Nu if there is an edge from u to v and Au;v=0 if not. If we treat R as a vector over web pages, then we have R=cAR. So R is an eigenvector of A with eigen value c. In fact, we want the dominant eigenvector of A. It may be computed by repeatedly applying A to any non-degenerate start vector.”

What is an eigenvector? Glad you asked. “In linear algebra, an eigenvector or characteristic vector of a linear transformation is a non-zero vector that only changes by a scalar factor when that linear transformation is applied to it.” Here’s the point: Google’s success derives in large part from a fiendishly clever mathematical algorithm that ranks the importance of Web pages.

But before you begin to feel that all this is just too complicated and mathsy for ordinary folks like us, note that in practice Google often answers queries by directing users to the Wikipedia page containing the search term in its title. That’s not got anything to do with links, let alone eigenvectors, but is simply a quick solution to getting reasonably well-structured answers to simple queries. In other words, it’s a practical fix that implies the complicated math-driven method fails. It’s not particularly clever, let alone elegant—but it works.

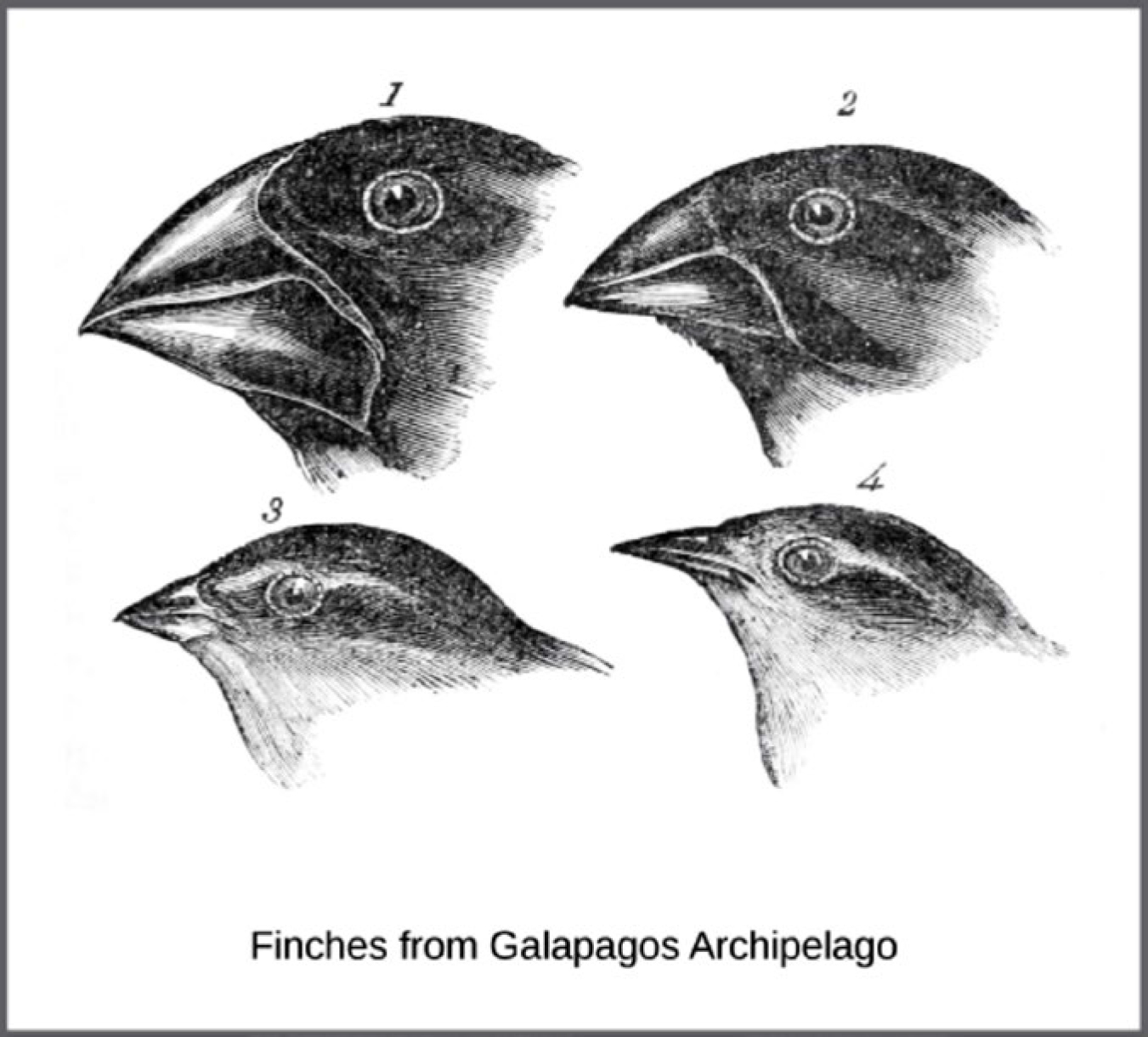

The big idea, then, behind Google emerged by chance from a swirl of scholarly (not business) debate. Even the name Google itself emerged from events with a random, not to say Darwinian, flavor. When I say “Darwinian,” I mean an approach that is free and open at the outset but then systematically reduces itself to a sole possibility. Before natural selection can act to favor a feature, you need to have a range of traits to select from, a range provided by the ways in which individual animals (whether humans, giraffes, or finches, as shown on the next page) are different from each other. Likewise, sometimes unexpectedly interesting results can be obtained by adding a random word to a search query. Try it sometime! More generally, working off-topic words and themes into your thinking is one way to prompt new insights and discovery.

Darwin’s big idea, then, the one that changed the way we see the world, was that evolution is a two-step process: random mutation is the raw material creating a range of possibilities, and natural selection is the guiding force that cuts them all down to just one. In a similar way, randomness and order combine in Google’s algorithms.

The website Conservapedia has long noted that Google is a big promoter of Darwin and atheistic science even to the point of giving special recognition to the anniversary of his birthday, which the search engine calls Darwin Day. Now, Conservapedia is an American encyclopedia project written with a narrow political agenda, but on this they are right: if you want to understand the driving philosophy of Google, you can do a lot worse than returning to the ideas of Charles Darwin—in particular, the conviction that life on earth is a kind of vast, random experiment in which only the fastest, strongest, fittest life-forms survive. Nor, in fact, do you have to look too hard to see that the views and ideas of this great English theorist seem to predominate in this twenty-first-century Californian enterprise. The nineteenth-century naturalist whose insights would rapidly spread from botany and biology to influence fields as diverse as politics, sociology, and even art is truly the ghost in the Google machine.

The idea that randomness and order can combine effectively is behind both Darwin’s theory and in Google’s algorithms. This famous image is supposed to illustrate how natural selection led to very different beaks for the finches of the Galapagos. (Darwin, Journal of Researches into the Natural History and Geology of the Countries Visited during the Voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle Round the World, 2nd ed. London: John Murray, 1845. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2010582#page/7/mode/1up.)

That said, whatever the Google philosophy really is, it seems to take second place to practical requirements. Illustrative of this is the fact that, originally, Page and Brin called their search engine BackRub, which has nothing to do with rubbing backs but instead, in their minds, something to do with back links. Would you use a search engine called BackRub? Me neither, especially if I were seeking objective information from an array of similar products. Fortunately, one day in September 1997, Page invited several other graduate students, including Sean Anderson, Tamara Munzner, and Lucas Pereira, to brainstorm better names for the new search technology.

Anderson suggested the word “googolplex,” and Page responded verbally with the shortened form, “googol.” Ten squared (or ten raised to the power of two) is a hundred, and ten cubed (or ten raised to the power of three) is a thousand, but a googol is 10100, ten raised to the power of a hundred. In decimal notation, it is written as the digit 1 followed by one hundred zeroes: 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,

000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.

The computer nerds all liked the idea so much they immediately checked whether it was available as a domain name on the Internet. However, by mistake (chance!), Anderson entered the name as “google.com,” and it was this that was found to be available. Page still liked the name, and within hours he took the step of registering it. The domain name record is dated September 15, 1997: Google’s birthday.

The search engine’s evocative name thus came about by chance. The other elements of Google were much more calculated but at the same time play less of a role in explaining the company’s success. After all, in the mid-1990s, just as Google was coming into existence, other equally smart people were developing search engines. Even the key Google concept of PageRank is influenced by other studies of how academic citations reflect the relative value of papers (notably the research by Eugene Garfield in the 1950s at the University of Pennsylvania) and by the creation of HyperSearch, at the time a revolutionary new kind of search engine, by Massimo Marchiori at the University of Padua.

Nonetheless, the reality that Google is a creature that has always competed in the Internet jungle and had to survive by being bigger and better than everyone else—rather than being actually new and different—is underlined by the fact that today, although the name PageRank is a trademark of Google, and the PageRank process has been patented, the patent is actually assigned to Stanford University, not to Google. However, Google has exclusive license rights on the patent for which, in return, the university received 1.8 million shares. The shares were sold in 2005 for $336 million. Peanuts! All of which goes to emphasize that Page and Brin’s genius does not lie in “invention” but rather in being able to commercialize the technology first—put another way, in being the fastest to adapt.

And so we turn to the book that seems to have had a remarkable influence on the Google founders—even if they’ve never referenced it publicly. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life was originally published way back in 1859 and has never been out of print.

Although Darwin’s book was remarkable for its scientific details, that is not why it had such political impact. Rather, there’s another aspect to Darwin’s theory, which is the conviction that life on earth is perpetually engaged in a zero-sum struggle for existence. And this other, characteristically Darwinian, element that has helped transform Google from a start-up launched in a garage to a colossus with ambitions to become the world’s first media company with revenues of a trillion dollars ($1,000 billion) is less playful. Everyone’s heard tales about Google’s quirky, fun side, including mouthwatering stock options, perks such as free meals and massages, and a daunting and sometimes just plain weird recruitment process. But running through the company’s DNA is also a darker strand: a ruthless killer instinct.

ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES

AUTHOR: CHARLES DARWIN

PUBLISHED: 1859

Rarely has a scholarly work so deeply influenced modern society and thought. The book itself has a curious history. It started as a much longer compendious account of all Darwin’s research into the riddle of life on this planet. Darwin’s idea was originally to organize and record the key points of some 2,500 diary pages and notes made while traveling the world on the ship HMS Beagle. This famous voyage from 1831 to 1836 had taken in the Cape Verde Islands; coastal regions of Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina; and the Galapagos Islands, to name only the most famous destinations. Darwin, we might say, had been busy following the “try everything, no preconceptions” approach. But then chance changed his plans significantly.

By June 18, 1858, Darwin had finished a quarter of a million words and even had a working title for what he envisaged as a three-volume account: Natural Selection. But that day he received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace, an English socialist who had been collecting botanical specimens in the Malay Archipelago. In his letter, Wallace sketched out a theory very like Darwin’s own!

Fearing that his own work would be overtaken by Wallace’s, Darwin immediately resolved to write a much briefer abstract of his ideas, and it is this shorter and much more readable account that became the book that would change the world.

This instinct (along with extraordinary chutzpah) has led Brin and Page to take on the world’s biggest corporate animals. This is the dark side of the “try everything, no preconceptions” mindset. Sometimes it seems as if Google has never come across an industry it doesn’t want to disrupt. The behemoth has spread its tentacles into an ever-growing array of businesses, including advertising, telecoms, and digital-navigation software. It’s started using drones to deliver medical supplies and even takeaway food to Googlers’ doors. The company’s habit of selling services cheaply or giving them away for free has endeared it to consumers—and outflanked regulators. But the same tactics have enraged competitors, who complain their new rival is out to destroy the economics of entire industries.

One of the biggest potential competitors was Microsoft, sometimes nicknamed the Beast of Redmond (or was the company in reality already less of a dangerous beast and more of a clumping great dinosaur?). In 2003, Brin told the New York Times that he wouldn’t knowingly challenge Microsoft: “We are not putting ourselves in the bull’s-eye as Netscape did,” he said, referencing Netscape’s disastrous battle against Microsoft Explorer to be the world’s choice of Web browser.

And yet only a year later (in the company’s 2004 initial public stock offering), Microsoft was precisely listed as one of three strategic competitors, and in 2006, when Google’s then chairman, Eric Schmidt, was asked who the company’s main rivals were, he listed just two: Yahoo, because, like Google, they had “a targeted advertising network,” and Microsoft, because it had plans to enter the search market. It’s not entirely clear how Yahoo’s cofounders, Jerry Yang and David Filo, felt about being seen as a strategic enemy considering they’d originally lent the Google founders a generous hand to get started. But then, it’s a jungle out there!

Not that that’s how Brin explained the company policy at an executive Q&A for a Google press day: “We just certainly see the history with that particular company, Microsoft, behaving anti-competitively, being a convicted monopoly and not necessarily playing fair in other situations—like Netscape and whatnot,” he said, before adding sanctimoniously, “so I think we want to focus early on and make sure that we at least are looking at the areas where perhaps power can be abused.”

What this meant was that within the company spirit of “trying everything,” Google had soon thrown down the gauntlet on virtually every path that Microsoft was following. As Janet Lowe describes in her book Google Speaks: Secrets of the World’s Greatest Billionaire Entrepreneurs, they opened a recruiting office not far from Microsoft’s office in Redmond, Washington, and made raids on Microsoft’s talent pool. They developed and offered free Google Apps, an online productivity software similar to Microsoft Office. Then came Gmail, also free, and in 2008, Google launched Chrome, the free browser that challenged one of Microsoft’s most lucrative products, Internet Explorer.

“The benefit of free is that you get 100 percent of the market,” Eric Schmidt, Google’s chief executive, explained to Ken Auletta, an American writer, journalist, and media critic for The New Yorker, in an interview. “Free is the right answer.” For Google, perhaps, but for both its competitors and other more humble life-forms, like regional newspapers and authors, free was often unsustainable. For many, as Auletta puts it, “‘free’ became a death certificate.”

WOLVES

If, occasionally, Google helps young start-ups, it can more usually be found clawing to pieces elderly prey. Because, above all, in Darwin’s theory, nature is red in tooth and claw. Animals and organisms compete to survive and prosper. At one point in Origin of Species, Darwin offers, “In order to make it clear how, as I believe, natural selection acts, I must beg permission to give one or two imaginary illustrations. Let us take the case of a wolf which preys on various animals, securing some by craft, some by strength, some by fleetness; and let us suppose that the fleetest prey, a deer for instance, had from any change in the country increased in numbers, or that other prey had decreased in numbers, during the season of the year when the wolf is hardest pressed for food.”

Darwin’s answer is emphatic: “I can under such circumstances see no reason to doubt that the swiftest and slimmest wolves would have the best chance of surviving, and so be preserved or selected.”

Of course, business executives know it’s a rough, tough world. However, Microsoft’s chairperson, Steve Bulmer, wasn’t keen for his company to become someone else’s dinner, let alone just another fossil. He declared in public, unambiguously, “I’m going to f***ing kill Google.”

Yet at the Googleplex, on the surface at least, there was no such passion. Instead, there was only a steady if rather dull fine-tuning of methodologies. There is a revealing conversation with Sergey Brin, back in 2009, explaining how he and Larry Page created a multibillion-dollar business in just a few years. “We’ve been very successful with advertising,” he said. You could say that again! Indeed, Google makes its money by selling advertisements, typically for a handful of cents. The clever bit is it sells vast numbers of them.

Curiously, when they were at Stanford, Page and Brin criticized search engines that had become too “advertising oriented.” And when, for many years, Google listed ten ingredients for corporate success prominently on its website, item one was that placement or ranking in search results is “never sold to anyone.” “These guys were opposed to advertising,” Auletta quotes Ram Shriram, one of Google’s first investors, in his book Googled: The End of the World as We Know It (Penguin, 2009). “They had a purist view of the world.” Presumably the “no preconceptions, try everything” strategy eventually won out over their ideals.

In reality, a “roll the dice and see what works” Darwinian (Bransonian?) approach was always ideally suited to Google’s core business of search advertising. The Internet is so big that you have to use some sort of algorithmic process to organize it, and it takes a vast series of logical experiments to fine-tune search results and the delivery of advertising around them. Within Google’s ecosystem, products like AdSense, which is currently the key driver of the company’s profitability, force businesses to compete for key words and only reward them if they choose the right ones.

Right from the start, Google refused to run with the herd, eschewed taking banner ads, and kept quietly building its own system linked to things people might be looking for. Brin has explained that ads related to searches were originally considered junk content not worth much, while affiliate fees barely paid for the pizza, and so Internet companies had tended to compete for the more lucrative banner ads that sit at the top of pages. Instead, Google ruthlessly upended the whole multibillion-dollar world of advertising. “It required a lot of evolution and a lot of work, but it happened,” Brin said to journalists at the 2009 Google I/O annual conference for developers, adding, “If you give it time to evolve and give people a chance to experiment, much as it took us in search a long time to find the magic answer . . . several generations later, we have what you think of now as AdWords, which works very well” (emphasis added).

Here, indisputably, are the key ingredients of the Google mindset: experimentation, evolution, and testing—this last guided not only by their engineering training but also by the laws of nature themselves. Indeed, the engineering mindset, the Lego-modeler’s mindset, is very different from that of traditional business thinking. You test theories through controlled experiments, and you make decisions based on experimental data. It’s a Darwinian marketplace of ideas in which only the fittest creations survive. Yet there’s always a randomness, an element of chance there.

Darwin himself once said, “I love fools’ experiments. I am always making them,” in which light, he would surely have welcomed Google’s seemingly random investments in businesses like Shweeb, an ecofriendly monorail transport system powered by passengers kicking their legs as if on a bicycle. Daft? Maybe. Google gave the company $1 million. Then there’s Clearwire, a wireless communications network. At the time, Google said Clearwire would “provide wireless consumers with real choices for the software applications, content and handsets that they desire.” Google liked the concept so much it chipped in $500 million. Brave? Yes. Unfortunately, the company shut down in 2015.

And then there is 23andMe, a trendy start-up founded by Anne Wojcicki, health care analyst and wife of Sergey Brin. Indeed, this initiative was supported by a personal loan of $2.9 million from the man himself. 23andMe offers to decode your DNA if you provide a saliva sample and a fistful of money. Google put a shade under $4 million into the project, but the thinking in this case may have been rather less driven by a taste for risky investments and more by a taste for keeping Brin’s cash safe, as one of the first things the company did with its new investment was to promptly pay back his original stake!

That reminds me that, actually, Google is not as indifferent to spending as its enormous wealth might lead you to imagine. According to a Forbes piece on penny-pinching billionaires, David Cheriton, the Stanford professor who introduced Page and Brin to the venture capitalists at Kleiner Perkins and who subsequently became a billionaire, is a man who reuses tea bags. Reuses tea bags! It’s bad enough to use bagged tea in the first place.

To sum up, Darwin’s little book seems to have contributed to Google’s willingness to experiment now and see what works later. However, there’s that other aspect of the company’s philosophy, the one that is Darwinian in a more ruthless sense. This is the conviction that in order for a few to succeed, many must perish. And as we’ll see again and again in this book, it’s also a reminder that it is not only people that are influenced by books; books themselves are too.

Darwin is supposed to have arrived at his insight as a result of observing animals on the Galapagos Islands during the voyage of the Beagle, but the real root seems to have been a famous book, written in 1798, by the English economist Thomas Malthus called An Essay on the Principle of Population. It is here that Malthus, obsessed with the dangers of overpopulation, warns that humanity is locked in a “struggle for existence” in which only the fittest survive and that “it follows that any being, if it vary ever so slightly in a manner profitable to itself . . . will have a better chance of survival, and thus be naturally selected.”

It is known that Darwin read Malthus’s essay, was much impressed by this notion, and merely expanded this theory of struggle among humans to the wider sphere of the plants and animals.

Recall that for many years, Google’s motto was “Don’t be evil” (it changed to “Do the right thing” in 2015), yet, as Michael Mace has noted, time and again, Google has identified a competing technology or idea, targeted it, and then gobbled it up whole. Mace adds that the behavior is a natural outcome of the way the company works. “Page says he’s all about cooperation and I think he means it, but his product teams relentlessly stalk the latest hot start-up. The result is a company that talks like a charitable foundation but acts like a pack of wolves.”

One of Page’s key strategic moves for Google illustrates this approach. Anxious to strengthen the company’s position in the sphere of mobile technology, Google bought Motorola Mobility for over $12 billion. The purchase was certainly disastrous for the Motorola workforce, who were slashed from 10,000 to 3,800 (AP, 2014). Despite this, Google continued to hemorrhage money, and shareholders pressured Page and Brin to call off the experiment. On January 29, 2014, Google announced the sale of Motorola Mobility to the Chinese PC maker Lenovo for $2.91 billion. Now, I’m not a math fiend like Brin or Page, but that looks like quite a steep drop in value. Or was it asset stripping? Google did keep bits of Motorola—notably some of their intellectual property. But this is the logic of Darwin: most of Motorola was struggling so had to perish. The successful parts, though, were given a chance to evolve and multiply. As Darwin put it, “A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections—a mere heart of stone.”

And yet, and as I say, quite unabashed, Google prides itself on being a highly principled company pursuing the good of humanity and for many years (up until 2015 when it mysteriously disappeared) it used the motto “Don’t be evil” within its corporate code of conduct. Nonmathematical, nonengineering types misread this. They assume it must mean “don’t do bad things,” but the evolutionary approach doesn’t allow for right and wrong, only for what works. For Google, and nature, “evil” is weakness, and strength and triumph are the only acceptable outcomes.

Reducing morality to self-interest and survival skills has always been controversial, but Darwin himself didn’t shy away. In fact, Darwin openly extended his theory to cover the human race and therefore challenged many social, ethical, and psychological assumptions. While Origin is his most admired work, he wrote others, such as The Descent of Man (1871), which are full of political advice:

With savages, the weak in body or mind are soon eliminated; and those that survive commonly exhibit a vigorous state of health. We civilized men, on the other hand, do our utmost to check the process of elimination. We build asylums for the imbecile, the maimed and the sick; we institute poor-laws; and our medical men exert their utmost skill to save the life of every one to the last moment. There is reason to believe that vaccination has preserved thousands, who from a weak constitution would formerly have succumbed to small-pox. Thus the weak members of civilized societies propagate their kind. No one who has attended to the breeding of domestic animals will doubt that this must be highly injurious to the race of man. It is surprising how soon a want of care, or care wrongly directed, leads to the degeneration of a domestic race; but excepting in the case of man himself, hardly anyone is so ignorant as to allow his worst animals to breed.

Coming back to Google, there’s another revealing story told about the company. In 2001, when Google was only a few years old, Page and Brin decided that the structure had become flabby and unresponsive. They called everyone to a meeting and told them that they were fired. The company was organized instead into small teams that attacked particular projects. (Some were later rehired.) This was, for them, the logical way to ensure that the wolves of Google were the fastest and fleetest.

What about the people’s feelings? As to that, an interview in The New Yorker with Barry Diller, onetime movie mogul, offers a clue. Diller, it seems, was rather put out by what he felt to be the arrogance of the Google founders. He described visiting Page and Brin in the early days of the company and being disconcerted that Page, even as they talked, stared fixedly at the screen of his personal digital assistant (PDA). “It’s one thing if you’re in a room with 20 people and someone is using his P.D.A.,” Diller recalled.

I said to Larry, “Is this boring?”

“No. I’m interested. I always do this,” Page said.

“Well, you can’t do this,” Diller said. “Choose.”

“I’ll do this,” Page said matter-of-factly, not lifting his eyes from his handheld device.

Page, it seems, lives in a parallel universe of machines and not emotions. Likewise, his company, even though it hunts in a technological world where things change very fast and even though the Darwinian philosophy it is built on stresses the danger of failing to adapt fast enough, takes a detached and long-term view. Page himself likes to talk about a fifty-year planning horizon, which sounds mad to most business strategists. Most companies have a planning cycle that doesn’t run to even one year but rather is worked out in pursuit of quarterly goals. Google does just the opposite.

And all the time, the very software that runs Google searches embodies the principles of Darwinian thought. Algorithms compete to satisfy the Internet searchers. Those whose findings meet expectations will flourish, and those that fail must shrink in importance and eventually perish.

How did Darwin’s theory come to have such a hold not only over Google’s scientists but on the way we all think? Part of it, as I say, must be because it is a powerful general theory with social and political dimensions. Origin of Species has had profound implications not only for understandings of biology and nature but also for our views of human societies and morality. Nazism and Marxism both were, in the minds of their founders, Darwin’s theory applied to politics.

And Darwinism explains how simple rules can lead to complex outcomes. How, for example, in living organisms, complexity emerges as the result of simple chemical reactions following certain laws. It is these more complex molecules that build up to become cells and these cells that in turn interact to become specialized organs. Organs interact to form organisms, which interact, communicate, and reproduce on ever higher scales to form, eventually, the universe.

Within Google’s search engine too there are virtual molecules, again guided by rules, which together create a new kind of artificial intelligence that increasingly guides our own thinking and behavior. But what if the search engine itself were really alive in the sense of possessing some kind of consciousness, what then might it be thinking? Surely it would be something like this: “From my early youth I have had the strongest desire to understand or explain whatever I observed. . . . To group all facts under some general laws.”

As a Google search will show you, in a fraction of a second, these are the words of Charles Darwin.