3

Save the Planet—One Page at a Time!

Books have played a key role in widening the circle of human concern to include the natural world and the environment. But what inspired their authors? For some of them at least, it seems that it was not so much dry facts or even direct experiences as imaginary tales in which nature was just one character in a compelling human narrative. Such books can range all the way from grand literary monuments to humble children’s stories.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring is a true example of a book that has changed the way people see the natural world. Indeed, it is considered one of the most influential green polemics ever written. It asks hard questions about whether and why humans have the right to control nature, to decide who lives or dies, or to poison and destroy nonhuman life. And, in many ways, its author seems to have been always destined to be interested in nature and the environment. Nevertheless, it turns out that the precise direction her interests took, and her success in communicating her passion, owe a lot to Moby Dick, written a good century earlier by New York–born Herman Melville.

The debt that Carson’s writing owes in stylistic and emotional terms to Melville is amply reflected by the fact that her first three books, Under the Sea Wind (1941), The Sea around Us (1951), and The Edge of the Sea (1955) were all, well, about the sea! This from someone born and brought up in inland United States, 350 miles distant from the Atlantic Ocean. Like Moby Dick, all these were gripping accounts of the interaction of human and marine life in the open seas. In these first books, Carson wrote about how islands were formed, how currents change and merge, how temperature affects sea life, and how erosion impacts not just shorelines but also salinity, fish populations, and tiny micro-organisms, embracing a larger environmental ethic including all of nature’s interactive and interdependent systems. Carson applies a cool, scientific eye to such questions.

On the surface, though, Melville’s novel is a very different kind of writing. It is supposed to be sailor Ishmael’s account of the obsessive quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship Pequod, to exact revenge on Moby Dick, the giant white sperm whale that on the ship’s previous voyage bit off Captain Ahab’s leg at the knee. The New Yorker says of it, “Moby Dick is not a novel. It’s barely a book at all. It’s more an act of transference, of ideas and evocations hung around the vast and unknowable shape of the whale, an extended musing on the strange meeting of human history and natural history” (Philip Hoare, “What Moby Dick Means to Me,” November 3, 2011).

MOBY DICK

AUTHOR: HERMAN MELVILLE

PUBLISHED: 1851

(ORIGINALLY UNDER THE TITLE THE WHALE AND SOMETIMES HYPHENATED TOO)

Moby Dick is considered one of America’s greatest literary works. It is the story of one man, Captain Ahab’s, quest for revenge on a whale that on a previous voyage bit off his leg at the knee. Among the characters of the boat called the Pequod are First Mate Ishmael and his friend Queequeg, the latter of whom falls ill, prompting a coffin to be built in anticipation of his demise. Later on in the story, the coffin becomes a lifeboat for Ishmael. (An image we might, slightly irrelevantly, note that Hergé, creator of Tintin, plays with evocatively in his tale “The Cigars of the Pharaoh.”)

Without spoiling the plot, it is fair to say that Moby Dick is eventually tracked down, and a great fight ensues in which the whale is victorious, the ship is destroyed, and everyone is killed—except Ishmael. (Well, maybe I have spoiled it a little.)

The enduring appeal of the book lies in two quite different elements. The first is a rich narrative style in which multiple threads are intertwined, including religion, human psychology, and ethics. But the second element is much more direct and practical: the descriptions of nature and the sea. Melville himself had firsthand experience of whaling, having spent time aboard a whaling vessel called the Acushnet. He also conducted detailed research for his book, reading about, among other things, the real-life drama of a whaling vessel called the Essex that in 1820 was attacked by a sperm whale thousands of miles off the coast of South America. The Essex sank, and the twenty-man crew was forced to make for shore—suffering dehydration, starvation, and exposure on the open ocean—in the ship’s whaleboats. Soon after they made landfall, the survivors resorted to eating the bodies of the crewmen who had already died. When that proved insufficient, members of the crew drew lots to determine whom they would sacrifice so that the others could live!

That was an influence on the author, though not on the tale itself, which is essentially focused on the life-and-death struggle of the crew of the Pequod and the slow but inexorable turning of the wheels of fate.

What does a grand story about human obsession and revenge have to do with the science of pesticide use? On the face of it, nothing at all, and the link has been downplayed by Carson’s biographers. Nonetheless, I am sure that one tale did lead to a world-changing other. It is in the emotional content that the debt to Moby Dick lies. This says a little bit about how books work and how one book can lead to another—and a whole lot more about the subtle ways in which our lives can be influenced by them.

On May 27, 1907, Rachel Louise Carson was born on a sixty-five-acre farm on a hill just up the Allegheny River from Pittsburgh. Her father was an insurance salesperson, but her mother seems to have had the greater influence on her life. A former schoolteacher (and before that a singer), she gently instilled in her daughter a passion for nature and the outdoors, aided by Anna Botsford Comstock’s Handbook of Nature Study, the surrounding lush woods and waterways all of which combined to become her classroom. She once wrote in The Saturday Review of Literature that she had taught her daughter “as a tiny child joy in the out-of-doors and the lore of birds, insects, and residents of streams and ponds.”

As a child, Rachel loved reading, and she began writing stories (often involving animals) at age eight. Her first foray into publishing, at the tender age of ten, was with a story printed in Saint Nicholas magazine, a monthly that included among its contributors authors Louisa May Alcott, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Mark Twain, Laura E. Richards, and Joel Chandler Harris.

An early favorite seam of reading was Beatrix Potter’s tales of rabbit families, but these were later followed by the novels of Gene Stratton-Porter, herself an early nature campaigner, especially on behalf of birds, while in her teen years the sea was a common thread brought alive in the novels of Herman Melville, Joseph Conrad, and Robert Louis Stevenson.

At college, Carson originally opted to study English, but with the encouragement of biology professor Mary Scott Skinker (and this despite the fact that career opportunities for women in the sciences were extremely rare at that time), she soon switched to biology, eventually earning a master’s degree in zoology. Despite initial concerns that, in her new field, she would have to give up writing, Carson discovered that the new focus actually gave her “something to write about” (as Linda Lear notes in her autobiography Rachel Carson [1997, 80], referencing correspondence by Carson. Indeed, Lear uses the phrase as the title for the fourth chapter in the autobiography).

Carson might have continued working toward a doctorate, but in 1934, at the height of the Great Depression in the United States, she was forced to abandon her studies in order to seek a full-time teaching position to help support her family. And then, in 1935, her father died suddenly, leaving the family in financial straits and Carson solely responsible for the care of her aging mother. It was thus more out of need than desire that she took what was originally supposed to be a very temporary position with the US Bureau of Fisheries, writing radio copy for a series of weekly educational broadcasts about water life entitled Romance under the Waters. However, it would turn out to be a very fortuitous posting.

Her supervisor, Elmer Higgins, was an enthusiastic audience and thought the first pamphlet she wrote for them was more suitable for a magazine, saying, generously, that it was “too good” for the original purpose! He advised her to offer it to Atlantic Monthly instead, who in due course published it as “Undersea,” a vivid narrative of a journey along the ocean floor.

One of the readers of Atlantic Monthly was an editor at the publishing house Simon & Schuster, who promptly contacted Carson and asked if she could expand the essay into a book. This became in due course Under the Sea Wind (1941), which received excellent reviews even if it sold only modestly. In the meantime, Carson’s article writing expanded with features in Sun Magazine, Nature, and Collier’s.

And so, by 1948, Carson was working on material for a second book, a life history of the ocean. Chapters were serialized in various publications, including The New Yorker, and it was eventually published as The Sea around Us by Oxford University Press. Now Carson’s writing really took off. The book shot on to the New York Times best-seller list, where it remained for eighty-six weeks. It was serialized in abridged form by Reader’s Digest, and it won both the 1952 National Book Award for Nonfiction and the John Burroughs Medal. The Sea’s success led to the republication of Under the Sea Wind, which also became a best seller.

Carson herself became a minor celebrity and was inundated with demands to give talks and answer fan mail while she worked to convert the book into a documentary. This too was very successful, but Carson was unhappy at the editing of her work to make it suitable for the screen and from then on refused to sell film rights to her work. Nonetheless, unloved or not, the documentary proceeded to win the 1953 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Thus it was with the ground laid already that Carson turned her attention toward what would in due course be her legacy issue: the mass production and government-sponsored spraying of pesticides.

The result was that by the early years of the 1960s, Carson had already become famous for a series of books announcing that the natural world was under threat. Silent Spring in particular (the last book published in her lifetime) is a searing indictment of the threat to the natural ecological balance through such things as the overuse of pesticides and became one of the icons of the green movement in the United States in the 1960s.

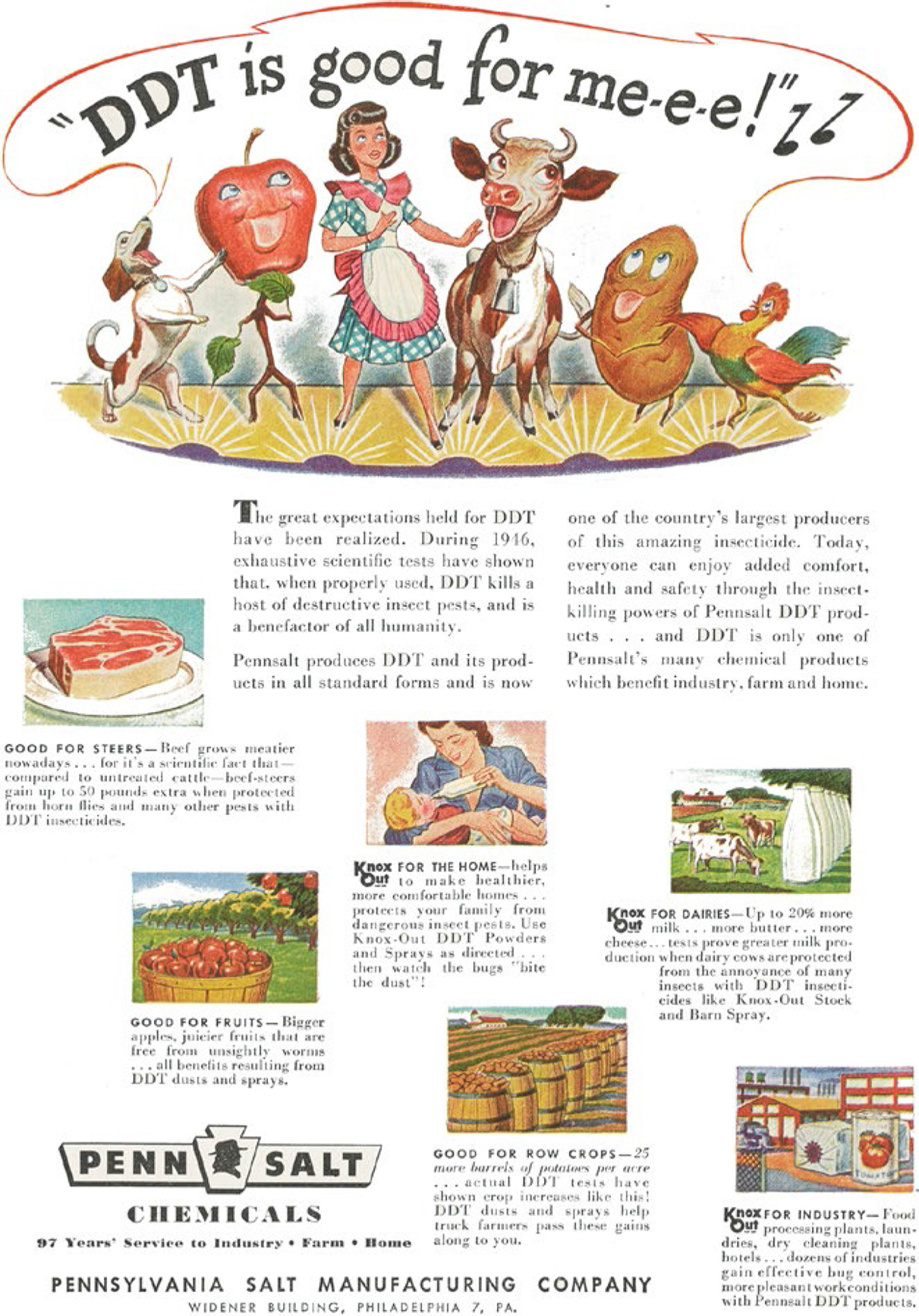

Whereas most writers, up to then, much admired the new age of science, Carson instead described “the chemical barrage” as being as crude a weapon as the caveman’s club, hurled against a fabric of life that was on the one hand delicate and destructible and on the other miraculously tough, resilient, and capable of striking back in unexpected ways.

However, it was only after a CBS Reports TV special, “The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson,” aired on April 3, 1963, that pesticide use really became a major public issue. The program included segments of Carson herself reading from Silent Spring interwoven with interviews with a number of other experts, mostly critics, such as Robert White-Stevens, a former biochemist and assistant director of the Agricultural Research Division of American Cyanamid, who told the public, “If man were to follow the teachings of Miss Carson, we would return to the Dark Ages, and the insects and diseases and vermin would once again inherit the earth.” According to biographer Linda Lear, “In juxtaposition to the wild-eyed, loud-voiced Dr. Robert White-Stevens in white lab coat, Carson appeared anything but the hysterical alarmist that her critics contended.” Reactions from the estimated audience of ten to fifteen million were overwhelmingly positive.

If a million people had already read her book, fifteen million more saw the TV show. Among them was President Kennedy, who announced that the federal agencies were taking a closer look at the problem after being asked about pesticide use during a press conference. It was, all in all, a remarkable journey for a child who had grown up in a rural river town in Springdale, Pennsylvania.

A 1947 advertisement for DDT to control household insect pests. Well into the 1960s, when Rachel Carson’s book was published, most writers much admired the new age of science. Carson instead described “the chemical barrage” as being as crude a weapon as the caveman’s club. (Wikipedia Commons, “DDT Is Good for Me-e-e!,” July 30, 1947. Science History Institute, Philadelphia. https://digital.sciencehistory.org/works/1831ck18w.)

In some ways, it was the careful research behind Silent Spring that made her words carry weight, but it was also true that the book, published by Houghton Mifflin on September 27, 1962, arrived at exactly the right time in history, just as a new idealistic generation started to see science not only as a savior but also as a threat. Silent Spring, in particular, marked a turning point in the understanding of the interconnections between human activities and their environmental consequences.

Carson’s position in the book is that chemicals play a sinister but littlerecognized role, similar to that of nuclear radiation—in changing the very nature of life. She attributed the recent decline in bird populations—in her words, the “silencing of birds”—to pesticide overuse. This is where the title comes from; it was initially just the title for the chapter on birds. The year 1959 brought the “Great Cranberry Scandal”: when it was discovered that three consecutive harvests of US cranberries contained increasingly high levels of the herbicide aminotriazole. Since this was known to cause cancer in laboratory rats, the sale of all cranberry products was halted.

As it says in Silent Spring, “The sprays, dusts and aerosols are now applied almost universally to farms, gardens, forests and homes—nonselective chemicals that have the power to kill every insect, the good and the bad, to still the song of birds and the leaping of fish in the streams—to coat the leaves with a deadly film and to linger on in soil—all this, though the intended target may be only a few weeds or insects.”

SILENT SPRING

AUTHOR: RACHEL CARSON

PUBLISHED: 1962

Silent Spring opens with a dark fable of an imaginary town in the American heartland in which a blight has fallen upon the land, turning hillsides that formerly teemed with wildlife into silent landscapes of “brown and withered vegetation, as though swept through by fire.” There is only one clue as to what might have happened: “the residue of a white powder that had fallen from the sky like snow a few weeks before.”

In the chapters that follow, the book weaves together carefully researched evidence on the effects of pesticides with more colorful and literary descriptions. The tale of Clear Lake, north San Francisco, for example: Once a popular fishing spot, noted for the western or “swan” grebe, whose nest floated on the lake’s surface, it had been repeatedly sprayed with DDT and various other chemicals to reduce the numbers of gnats. After three applications of insecticide, the gnats were still there but the grebe were dying. Autopsies showed that fatty tissue in the birds contained levels of the insecticide many times higher than had ever been sprayed. What had happened is that the insecticide had concentrated a thousandfold as it rose up the food chain. The plankton absorbed and concentrated the initial dose, then the fish ate the plankton, and finally the birds ate the fish, with the level of the pesticide multiplying many times over at each stage.

On land too, Carson pointed out that the practice of planting large monocultures created the conditions for insect explosions and unraveled nature’s own systems of checks and balances. She gave the simple example of Dutch Elm disease, which spread through the United States and Canada largely because town planners liked to line streets with a single varietal of tree. And she put the problem into a wider economic context too, saying that “pest control” was doubly misguided as the most pressing problem for agriculture in the United States at the time was that it was producing too much food, resulting in surpluses that had been created at public expense via government subsidies that also had to be dealt with at public expense. In the United States, pesticides were a solution in search of a problem.

The chemical industry responded to Carson’s call for careful use of insecticides by denouncing the idea of a world without any chemicals—and sought their own emotionally charged examples in response, such as the plight of children dying from mosquito-borne illnesses in African villages. Ironically, though, the critics spread Carson’s message and created interest in her book without actually persuading key figures in authority.

Carson’s main argument was that pesticides have such disastrous effects on the environment that they should really be called biocides—poisons whose effects are rarely limited to the target pests. Most of Silent Spring is devoted to describing their deleterious effects on natural ecosystems, but later chapters also detail cases of human poisoning, cancer, and other illnesses attributed to the chemicals.

This was all in the context of a postwar world in which scientists were considered infallible, chemicals were our friends, and certainly the government’s guiding light was the health and safety of its citizens. It was uncontroversial that regulation of insecticide use was the responsibility of the Department of Agriculture—a department otherwise busy encouraging and funding exactly that . Back then, the Environmental Protection Agency did not yet exist, much less campaign groups like Greenpeace.So when Carson warned of a world in which birds had disappeared and “the spring was silent,” she gave a voice to those who previously had none.

Serialization of Silent Spring began in The New Yorker, in the June 16, 1962, issue—the first nonfiction book to ever be featured in the magazine. Carson and the others involved with the publication braced for fierce criticism. It was not long in coming.

Barely had the second installment appeared than Louis McLean, the general counsel of Velsicol chemical company (exclusive manufacturer of chlordane and heptachlor) wrote to say it would sue if The New Yorker printed the next installment. The magazine went ahead anyway. Soon after, widening the attack to oppose publication of the book itself, McLean stated that “sinister influences” and “natural food faddists” were seeking to create the impression that “all businesses are grasping and immoral” and to reduce American agriculture to “east-curtain parity,” meaning the level of the communist countries of Eastern Europe. Many conservative politicians of the period firmly believed that environmentalists were a kind of Trojan horse movement employed by the feared communist regimes of the Soviet sphere.

One of the main manufacturers of DDT (Dupont) was also among the first to react, compiling an extensive report on the book’s press coverage and estimated impact on public opinion as well as joining with other companies to produce a number of brochures and articles of their own promoting and defending pesticide use.

Two chemists associated with the company American Cyanamid, Robert White-Stevens (mentioned above) and Thomas Jukes, were among the most aggressive critics, especially of Carson’s analysis of DDT. They attacked Carson’s scientific credentials, because her training was in marine biology rather than biochemistry, as well as her personal character. White-Stevens labeled her “a fanatic defender of the cult of the balance of nature.” The snidest attack of all came from Ezra Taft Benso, a former secretary of agriculture who would later become prophet of the Mormon Church. He wondered why “a spinster with no children” should be so concerned about genetics before immediately offering his own answer: because she was a communist.

Yet the attacks failed. Indeed, they only made Carson more influential.

In conjunction with a new grassroots environmental movement, Silent Spring spurred a reversal in national policy with the creation of the US Environmental Protection Agency, tasked with identifying and evaluating the “environmental impacts” of government policies. When the EPA officially opened its doors on December 2, 1970, it had a budget of $1.4 billion and 5,800 employees, many of whom “had an enormous sense of purpose and excitement,” as the first EPA administrator, Bill Ruckelshaus, put it as part of an oral history interview with Chuck Elkins. In the same interview, Ruckelshaus paid tribute to Carson’s role, saying, “I would say in 1962, things changed significantly when Rachel Carson wrote her book entitled Silent Spring, because this introduced a new element into the public consciousness about pollution because she identified the fact that invisible pollutants—in this case, pesticides—might be having damaging and maybe even permanent effects on the environment, particularly on the survivability of species. And so this brought into the environmental movement a whole other set of people with different concerns and different demands that the government ought to be doing something.”

Part of Carson’s effectiveness was in fighting science with science. After all, she began the four-year project of what would become Silent Spring by gathering examples of environmental damage attributed to DDT. She pulled together already-existing data from many areas and synthesized the information to create the first coherent account of the effects persistent chemicals had on the environment.

But another part, and probably the more important part, was that she had a knack for taking dry facts and translating them into lyrical prose that enchanted the public. It was this aspect that enabled Silent Spring to launch a revolution in attitudes at all levels of society, from schoolchildren to government and industrial leaders. Carson’s power lay in her scientific knowledge combined with poetic writing, which was far more effective than earlier calls to use modern technology responsibly that were made by people with only a superficial understanding of their topic.

Carson had been concerned about the use of synthetic pesticides, many of which had been developed through the military funding of science after World War II, since the mid-1940s; however, it was really the US federal government’s 1957 gypsy moth eradication program that prompted her to switch her research to focus on the issue. The gypsy moth program involved aerial spraying of DDT and other pesticides—mixed with fuel oil! Since the program mandated the spraying of private land, landowners on Long Island were able to file a lawsuit opposing the practice, and although they were ultimately unsuccessful in the suit, the fact that the Supreme Court granted the petitioners the right to gain injunctions against potential environmental damage in the future created the basis for later successful environmental actions.

In Silent Spring, Carson recounts the story of this campaign along with nearly a dozen other real-life horror stories concerning the misuse of chemical pesticides. One chapter, for example, entitled “Indiscriminately from the Skies,” details the American government’s disastrous 1957 campaign of chemical warfare on fire ants. The South American invaders, unintentionally introduced in the early 1920s, were certainly a nuisance, with their painful sting and large mounds, but on its own assessment the government had previously deemed them neither a pest nor a serious threat to agriculture. However, with the advent of new methods of chemical pest control, that all changed. Suddenly the fire ants had to die!

Enormous quantities of chemical poisons were injudiciously applied to twenty million acres of farmland in an effort to eradicate what the government now insisted was a threat to livestock, despite their earlier assertions to the contrary. The losses to wildlife—and the livestock that the spraying was supposed to protect—were widespread, disastrous, and easily attributed to the spraying program, even as the government continued to deny any connection. Carson contended that the “pest eradication” program was nothing more than an ill-disguised, poorly conceived public relations campaign to sell pesticides.

As her research progressed, Carson found a sizeable community of scientists who were documenting the physiological and environmental effects of pesticides. She also took advantage of her personal connections with many government scientists, who supplied her with confidential information. From reading the scientific literature and interviewing scientists, she realized that there were two scientific camps: those who dismissed the possible dangers barring absolutely conclusive proof and those who were minded more to the “precautionary principle” and ready to consider alternatives such as biological pest control.

The result of all this, as Mark Hamilton Lytle has put it in his biography The Gentle Subversive: Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, and the Rise of the Environmental Movement, was that Carson “quite self-consciously decided to write a book calling into question the paradigm of scientific progress that defined post-war American culture,” the overriding theme of which is the powerful—and often adverse—effect humans have on the natural world.

This is where Melville’s tale of whale hunting comes back in. It has well been noted that, in Doug McLean’s phrase, a “great herd of readers profess devotion to Herman Melville’s classic Moby Dick, but novelists especially seem to love saying they love it.” On The Top Ten, a website that lists authors’ favorite books, Moby Dick is cited more often than not (and by writers as dissimilar as John Irving and Robert Coover, Bret Easton Ellis, and Joyce Carol Oates). But, as McLean notes wryly, perhaps they all love a different Moby Dick. Because, at various times, it’s been called a whaling yarn, a theodicy, a Shakespeare-styled political tragedy, an anatomy, a queer confessional, and an environmentalist epic; and perhaps because this novel seems to hold all the world, all these readings are compatible and true. For Rachel Carson, the book seems to have inspired in two ways: first, in the insights it offers into marine life, and second, for the very different insights it offers into human motivations and psychology.

However, to understand the book’s influence on Carson, a few key passages will suffice. First of all, consider one of the central characters, Flask, the third mate of the whaling ship, and his motivations. Flask, we are told, is a native of Tisbury, in Martha’s Vineyard.

A short, stout, ruddy young fellow, very pugnacious concerning whales, who somehow seemed to think that the great leviathans had personally and hereditarily affronted him; and therefore it was a sort of point of honor with him, to destroy them whenever encountered. So utterly lost was he to all sense of reverence for the many marvels of their majestic bulk and mystic ways; and so dead to anything like an apprehension of any possible danger from encountering them; that in his poor opinion, the wondrous whale was but a species of magnified mouse, or at least water-rat, requiring only a little circumvention and some small application of time and trouble in order to kill and boil.

Flask is driven by a violent grudge against whales, a passion that keeps him on edge—but also prevents him from understanding how glorious and magnificent whales can be. Exactly the same attitude and folly govern human interaction with “the pests” of nature in Carson’s account. At the same time, it is the poetic quality of Moby Dick that seems to have transmitted itself to Carson and in turn made Silent Spring such a powerful plea on behalf of the environment. Melville talks of “the blending cadence of waves with thoughts” and of the ocean as a deep, blue, bottomless soul, pervading mankind and nature, and of “every strange, halfseen, gliding, beautiful thing” that flickers unseen through the depths, like so many elusive thoughts.

Indeed, contemplating the ocean depths, even Ishmael feels himself to be united to all of creation in a transcendent moment—reminiscent of the sentiments of American Romanticism in the mid-nineteenth-century writings of Henry Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. (Thoreau’s Journal was another of Carson’s favorite reads.)

One of Carson’s key themes is that science presents only a partial picture of nature. A passage in Melville makes a similar point:

The natural aptitude of the French for seizing the picturesqueness of things seems to be peculiarly evinced in what paintings and engravings they have of their whaling scenes. With not one tenth of England’s experience in the fishery, and not the thousandth part of that of the Americans, they have nevertheless furnished both nations with the only finished sketches at all capable of conveying the real spirit of the whale hunt. For the most part, the English and American whale draughtsmen seem entirely content with presenting the mechanical outline of things, such as the vacant profile of the whale; which, so far as picturesqueness of effect is concerned, is about tantamount to sketching the profile of a pyramid.

Above all, it is the link between whales and man that Melville makes that seems to inspire Carson’s own work. Because, in both the novel and the factual account, the truest picture of nature is the one that emerges through describing humanity’s relationship with it. Many years later, when CBS Reports presented “The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson,” Carson can be found saying, “We still talk in terms of conquest. We still haven’t become mature enough to think of ourselves as only a tiny part of a vast and incredible universe. Man’s attitude toward nature is today critically important simply because we have now acquired a fateful power to alter and destroy nature. . . . But man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself.”

At the end of Moby Dick, there is a scene in which the sight of the nowkilled and butchered whales seems to echo Silent Spring’s fear of a world to come in which man’s indiscriminate use of chemicals leads to a similar but land-based death of nature:

When I stand among these mighty Leviathan skeletons, skulls, tusks, jaws, ribs, and vertebrae, all characterized by partial resemblances to the existing breeds of sea-monsters; but at the same time bearing on the other hand similar affinities to the annihilated antichronical Leviathans, their incalculable seniors; I am, by a flood, borne back to that wondrous period, ere time itself can be said to have begun; for time began with man. Here Saturn’s grey chaos rolls over me, and I obtain dim, shuddering glimpses into those Polar eternities; when wedged bastions of ice pressed hard upon what are now the Tropics; and in all the 25,000 miles of this world’s circumference, not an inhabitable hand’s breadth of land was visible. Then the whole world was the whale’s; and, king of creation, he left his wake along the present lines of the Andes and the Himmalehs. Who can show a pedigree like Leviathan? Ahab’s harpoon had shed older blood than the Pharaoh’s. Methuselah seems a school-boy. I look round to shake hands with Shem. I am horror-struck at this antemosaic, unsourced existence of the unspeakable terrors of the whale, which, having been before all time, must needs exist after all humane ages are over.

Carson once remarked to her friends that while it was clear where her love of nature had originally come from, there was something of a mystery about where her love of writing originated. Surely Moby Dick fills that gap. However, for her readers, it is her ability to offer them a way to see the world from new perspectives that matters. And this is exactly the gift that another highly influential environmentalist, Frans Lanting, offers too, in his books that combine text with images.

Recall that Carson once explained that in writing Under the Sea Wind, in particular, she chose to tell her story from the point of view of the fish and other creatures whose world she wished to enter and explore. As biographer Mark Hamilton Lytle puts it, quoting a section of her correspondence with a friend, “their world must be portrayed as it looks and feels to them—and the narrator must not come into the story or appear to express an opinion.” This was to avoid “human bias” and also to inject power and immediacy. The same aim and ambition reappears even more emphatically in the writing and photography of Lanting.

Today, Lanting is considered one of the great photographers of our time. His work appears in books, magazines, and exhibitions around the world but perhaps most notably in National Geographic magazine. Born in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, he earned a master’s degree in economics before moving to the United States to study environmental planning. It was soon after this that he began photographing the natural world, documenting wildlife from the Amazon to Antarctica “through images that convey a passion for nature and a sense of wonder and concern about our living planet,” as his website puts it. Lanting also recalls “living with albatrosses” on an island in the Atlantic Ocean and how at such times he “shrank in size and learned to see the world through other eyes.”

Lanting’s work has been commissioned frequently by National Geographic, and assignments have ranged from the bonobos of the Congo to incredible images of penguins as part of a circumnavigation by sailboat of South Georgia Island in the sub-Antarctic. In a remote part of the world, he spends weeks on platform towers to obtain rare tree-canopy views of rainbow-colored macaws, frogs in flight, and orangutans swinging on vines. He has lived for months with seabirds on isolated atolls in the Pacific Ocean, tracked lions through the African night, and camped among giant tortoises inside a volcano in the Galápagos.

Lanting is quite open about the fact that, in all of this, he was deeply influenced by a book. So, as an environmentalist, was he too, perhaps, inspired by an epic tale of the struggle between Man and nature like Melville’s? Not at all; that is not how books work. Influences are much more individual and unique. In his case, he takes as his ideal the tale of a child who becomes so close to a flock of geese that he is accepted as one of them. This is Lanting’s arena, poised somewhere between the worlds of man and nature, an ambassador from one to the other.

The children’s classic The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, published in 1906 by Selma Lagerlöf, is so famous in Scandinavia that everyone knows the plot, although it’s a long book and few have read it. (Of course, not being read didn’t stop Lagerlöf becoming a Nobel Prize winner for her writing!) The short version, though, is that Nils, a good-for-nothing kid in late-nineteenth-century Skåne, angers the local tomte (a kind of elf or leprechaun), who magically transforms him into another tomte. Fortunately, Nils, now the size of a thumb, is adopted by a flock of geese who take him to their summer nesting grounds in Lapland. On the way, they travel all around Sweden, which for Swedish children is near enough to the whole world. In any case, as Lanting says, the geography is always firmly in the

In the introduction to his book Eye to Eye (1997), Lanting says,

During my youth in Holland I read a children’s book that made a deep impression on me . . . The Wonderful Adventures of Nils . . . tells the story of a boy who shrinks to the size of an elf, climbs on the back of a barnyard goose and joins a flock of wild geese migrating north. For a year Nils travels with the geese who introduce him to Eagle, Raven, Bear and other animals. He learns to see the world through their eyes. But when Nils finally returns to his family’s farm and regains his former size, he loses his standing amongst the animals. The geese, suddenly afraid of their companion, take off—but not until after they plead with him to become an advocate for their needs.

And he continues,

As sentimental as it may be, this children’s story has resonated with me, and even today it reflects some of my basic beliefs and aspirations as a naturalist. I have spent much of the past two decades in the company of animals, trying to understand and interpret their ways. The conditions under which I work are often a far cry from Nils’ intimacy with his wild geese. Long lenses, remotely controlled cameras, and other complicated contraptions—plus a great reserve of patience—are often prerequisites to overcoming the distance most animals like to keep from the camera.

Being tiny, of course, is an essential part of all young children’s experiences, as are Nils’s immediate worries in his new state: “Where would he get food and who would give him shelter, and who would make his bed?” It seems matters must turn even worse when he is accidentally borne away from home by the farm gander intent on following the wild geese to Lapland. There are echoes here to other fairy tales, notably Tom Thumb, and at one point Nils even reenacts the story of the Pied Piper when he saves a town’s grain stores by leading the rats away with a tiny pipe.

THE WONDERFUL ADVENTURES OF NILS

AUTHOR: SELMA LAGERLÖF

PUBLISHED: 1906

Perhaps it slightly spoils the book to discover that it was originally commissioned by the Swedish National Teachers’ Society as a geography textbook. But maybe the dusty origin inspired the author to greater imaginative heights, because Lagerlöf’s book is poetical and never allows the moralistic undercurrent to crush Nils’s naughty spirit as a child. Actually, Nils Holgersson starts the book as a very naughty boy: he locks his parents in the shed, trips up his mother as she is carrying milk, and is cruel to the animals on the farm. His comeuppance arrives at age fourteen on the day he traps a tomte, or house elf, and is shrunk as part of a lesson in what it is like to be tiny.

Reviewing the book for The Guardian, Philip Womack calls it “grand, beautiful, exciting and poignant,” offering one of the tales within the tale as particular evidence. This is an episode in which Nils wanders the streets of Vineta, a fine city where everyone dresses well and appears fabulously wealthy. The residents even offer him the chance to enjoy similar riches—in return for a single coin. Excited, Nils rushes off in search of one, but on his return the city has vanished. A stork then explains to him that what he saw was actually a ghost city that long ago had been drowned for its greed. Spookily, it reappears for just one hour each year, during which period of grace it has the chance to return to life, but only if someone buys something for one coin. Nils, who used to be so selfish and uncaring, is now so sad for the lost city that he bursts into tears. Similarly, at the end of the book, when Nils returns to the farm and his parents plan to eat his goose companions, he remonstrates with them, saying that it would be a real sin to eat a bird that has found its way home. In the manner of the best books, his parents yield and spare the goose.

In fact, what gives the book its spice and enables it to speak directly to children, rather than talk down as so many children’s books and their authors still seem to do, is the way Nils is able to transcend his parents’ limited perspectives and to see things anew. Significantly, when the elf offers to return Nils to full size and humanhood the boy refuses, preferring instead to remain with his animal companions and be wild and free.

Lanting was also affected by the story within the story. It turns out, according to the introduction, that Lagerlöf’s own original inspiration was a grim tale she was told by her grandmother about an incident that had occurred when the grandmother was herself a little girl. There had been a white gander on the farm, which one spring day took it into its head to fly off with a flock of wild geese who were passing by. The family was of course sure they would never see the white gander again. But many months later, the grandmother was astonished to see that the gander had returned. And he was not alone; during the summer, he had found a mate, a beautiful gray goose, and they were accompanied by half a dozen little goslings. Delighted, Selma’s grandmother led the goose family to the barn, where they could eat from the trough with the other fowl. She closed the door so that they wouldn’t fly off again and ran to tell her stepmother. And so to the awful ending. The stepmother said nothing. She just took out the little knife she used for slaughtering geese, and an hour later there was not one goose left alive in the barn.

For Lanting, this resonates with the moment in the book when Nils is awoken one night by a stork who says that if Nils follows him, the stork will show him something important. They fly to the seashore, where there is a strange city, quite unlike anything one would expect to find on the Swedish coast. Nils goes in through the huge gate and discovers people dressed in rich clothes from a bygone age. No one seems to notice him at first. He finds his way to the merchants’ quarter. People are selling all kinds of precious goods: embroidered silks and satins, gold ornaments, glittering jewels. And now he realizes that the merchants can see him. They are holding out their wares to him, offering all these treasures. Nils tries to make them understand that he could never afford any of it; he is a poor boy. But they persist and using gestures tell him that he can have anything he wants if he can just give them one small copper coin. He searches his pockets over and over again but finds they are empty. In the end, he leaves the city, and when he turns round again it has disappeared. “It is the lost city of the sea traders,” explains the stork. “They were drowned beneath the waves long ago, but once every hundred years they come back for a single night. The legend is that if they can sell a single thing to a mortal, they will be allowed to return to the world; but they never do.” Nils feels his heart is going to break. He could so easily have saved all these good people and their city, but he has failed them.

It seemed to Lanting that both stories expressed the same feeling. If only people had known what was needed to save the doomed merchants and the endangered animals they could have acted in time! If only. . . .

And so Lanting’s work is more than merely passive observation. He has profiled “ecological hot spots” from India to New Zealand and has created awareness of both the majesty and the plight of albatrosses, the threatened extinction of the Asiatic cheetahs of Iran, and the remarkable lives and behavior of chimpanzees in Senegal—research that meshes with Jane Goodall’s by expanding our appreciation of these animals and in the process shedding new light on what it means to be human.

Also in Eye to Eye, Lanting recalls a story of northwestern Native Americans—a culture in which wood carvings of animals are immortalized in totem poles and masks. He explains that one summer, while touring this coastal region, a Kwakiutl elder honored him by sharing a legend that belongs to his people.

He took me to a sacred cave on his island and there, surrounded by the sweet scent of cedars, we sat down and he told me this story:

Once upon a time, he said, all creatures on the face of the earth were one. Even though they looked different on the outside, they all spoke the same language. From time to time they would come together at this cave to celebrate their unity. When they arrived at the entrance, they all took off their skins. Raven shed his feathers, Bear his fur, and Salmon her scales. Inside the cave, they danced. But one day, a human, attracted by the commotion, crawled into the cave and surprised the animals in the act of dancing. Embarrassed by their nakedness they fled, and that was the last time they revealed themselves in this way.

There are similar stories in other traditions too; indeed there are echoes of paradise and Adam and Eve discovering the shame of nakedness here. But for Lanting, what is important here is the “mythical understanding” that underneath their separate identities all animals are one. This, he says, became the guiding principle for all his photographic work. “I aim to get past the feathers, fur and scales. I like to get under the skin. It doesn’t matter whether I am focusing on a three-ton elephant or a tiny tree frog. I want to get up close and face them, eye to eye.”

And thus we better understand now not only the title but the spirit of his book.

Above all, running through all Lanting’s books, is a recognition of our shared animal nature. Lanting says that he seeks to offer a different perspective, to emphasize animals’ own parallel worlds, to show their “full individuality” and also how animals operate as members of their own societies.

For Lanting, wildlife photography was partly an escape and partly a way to seek out animals on their own ground. “What my eyes seek in these encounters is not just the beauty traditionally revered by wildlife photographers. The perfection I seek in my photographic compositions is a means to show the strength and dignity of animals in nature.” His book is his tribute to that.

Lanting’s mission is to use photography to help create leverage for conservation efforts ranging from local initiatives to global campaigns, through his publications, alliances, public appearances, and active support of environmental organizations. He serves as an ambassador for the World Wildlife Fund Netherlands, on the National Council of the World Wildlife Fund USA, as well as on the Leadership Council of Conservation International.

The result is books that are stories as much as collections of images—from Eye to Eye (1997) to LIFE: A Journey through Time (2006) and onward too. “No photographer turns animals into art more completely than Frans Lanting,” says The New Yorker, but perhaps his own words are a more accurate description of his aims and hopes. Lanting says simply that his aim is to “give voice to the natural world.” Books, whether factual or fictional, textual or photographic, are our most powerful way to do that.