4

Search for Life’s Purpose

Abelief in taking control of your life is at the heart of the philosophy known as existentialism. That’s a long word and a rather off-putting one. But the key point about the philosophy is that it is concerned with essences and one essence in particular: the search for meaning in our own lives. We exist, yes. But to what ends, for what purpose? Sure enough, books and writing played a key role in shaping both Steve Jobs’s and Evelyn Berezin’s answers to that big question.

Let’s start with Jobs; one of my favorite quotes of his beautifully sums up the Apple supremo’s approach to life: “Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.”

That’s taken from his commencement speech for students at Stanford in 2005, when Jobs had already been diagnosed with cancer and was in a reflective mood, which is not to say that Jobs wasn’t always pretty reflective. Indeed, a full eleven years earlier, in a PBS program entitled One Last Thing, the title itself being an echo of his catchphrase at the hotly awaited Apple product launches, Jobs can be found saying something similar:

When you grow up, you tend to get told that the world is the way it is and your life is just to live your life inside the world, try to have a nice family, have fun, save a little money. That’s a very limited life. Life can be much broader, once you discover one simple fact, and that is that everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it. That’s maybe the most important thing. It’s to shake off this erroneous notion that life is there and you’re just going to live in it, versus embrace it, change it, improve it, make your mark upon it.

This older and wiser Jobs is here drawing on some very personal life experiences as well as one book in particular that profoundly influenced his thinking. As to the life experiences, though, way back in 1985, a young Steve Jobs in a shiny silk shirt and an oversize bow tie gave some big clues to David Sheff in a profile for Playboy magazine. For example, Jobs told Sheff, “When you’re a carpenter making a beautiful chest of drawers, you’re not going to use a piece of plywood on the back, even though it faces the wall and nobody will ever see it. You’ll know it’s there, so you’re going to use a beautiful piece of wood on the back. For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through.”

Why should something people will probably never see matter? But for existentialists it’s a no-brainer. The carpenter must be guided by their own values, and every aspect of the object they create has to be true to its function. For Jobs, as those working with him later found out all too well, what most people might think is “okay” is not good enough.

There’s no doubt that Steve Jobs was quite an imposing figure. But before Jobs became the visionary founder of Apple, he was just a pretty ordinary, middle-class kid growing up in California, being raised by his adoptive parents, Paul and Clara Jobs. His new dad was a kind of engineer, or more precisely a machinist for a company that made lasers. According to Steve’s fond account, he was “a genius with his hands” who was often tinkering in the garage. And he seems to have passed on to his adoptive son some key ideas, including ones about product design and the pursuit of perfection—ideas that would later be at the heart of the young Jobs’s success with Apple. Though less often noted, it is probably true that Clara, who was an accountant and may have contributed to Steve’s skills at raising seed capital for his ideas, also contributed her parental influence.

Walter Isaacson, author of probably the most detailed biography of Jobs, recounts a lesson from Paul that was particularly influential. It seemed that the young Steve once helped his father build a fence around their family home in Mountain View. While working, Paul told the boy, “You’ve got to make the back of the fence, that nobody will see, just as good looking as the front of the fence. Even though nobody will see it, you will know, and that will show that you’re dedicated to making something perfect.”

The story illustrates that long before Jobs read any philosophy, existentialist ideas had clearly struck with the result that, years later, as the CEO of Apple, Jobs insisted that every element of the Macintosh computer be beautiful, including the bits nobody would ever see, like the circuit boards inside.

But back to school. The young Steve Jobs hated it. Lessons bored him painfully, and he reacted by engaging in acts of disobedience and defiance. He was expelled from the third grade and then, in junior high school, one day he simply refused to go back. Fortunately for him, his adoptive parents decided to try to make a fresh start in another California town. They moved to Los Altos, California, near the heart of Silicon Valley.

Steve Jobs has a curious habit of being in the right place at the right time. After the move to Silicon Valley, ideas began to flow around the young teenager—not at school, not at college, but in the neighborhood’s garages. Many of his new neighbors were engineers who gathered in garage workshops after work and on weekends to talk and tinker with projects. One key player who lived just across the street was Steve Wozniak, whose father was an engineer at Hewlett Packard. “Woz” would become Jobs’s inseparable “other.”

Jobs explained years later that participating in these informal garage workshops gave him the realization that technology was the result of human creation, not “magical things that just appeared in one’s environment.” If there’s ever a stage play of the Steve Jobs story, for sure one dramatic scene will be set in the interior of a garage.

So it was that when he was just twelve or thirteen, at an age when most boys would be pleased to work out how to mend a battery light for their bicycle, Jobs could be found trying to build a digital frequency counter, which is a device to measure the oscillations in an electrical circuit and extremely cutting-edge stuff—not the kind of thing you can get in a local hardware store. That being so, he ended up needing some help, at which point, Jobs thought to pick up the phone and call Bill Hewlett, the CEO of Hewlett Packard, then one of the world’s most advanced technology companies. HP was a “local company,” a Californian company, and sure enough Jobs found Bill’s number listed in the Palo Alto phone book. As Jobs related it to Sheff, “He answered the phone and he was real nice. He chatted with me for, like, 20 minutes. He didn’t know me at all, but he ended up giving me some parts and he got me a job that summer working at Hewlett-Packard on the line, assembling frequency counters. Assembling may be too strong. I was putting in screws. It didn’t matter; I was in heaven.”

On his own account too, Steve’s summer job at Hewlett Packard was a key experience—yet it came about in this quite extraordinary way. After all, why did Steve want a frequency counter? No one else seems to have noted it, but such things are useful for hacking phone networks. This brings us back to Woz, Steve’s lifelong friend and vital collaborator. In fact, Wozniak was significantly older than Steve, at about eighteen, and he was, as Jobs put it in the Playbox interview, “the first person I met who knew more electronics than I did.” The two became good friends; they shared not just an interest in electronics but also a sense of humor. They pulled “all kinds of pranks” together, usually rather silly ones, like making a huge flag with a rude “up yours” symbol on it to unfurl in the middle of a school graduation, and one time they made something that looked and sounded like a bomb and brought it to the school cafeteria. Ah, innocent times—boys can’t play pranks like that now!

Nor indeed is it likely that the 1960 hacker generation could reproduce in today’s surveillance state such key parts of the Jobs-Wozniak learning curve as their development of technology for playing the “blue-box business.” This is hacker-speak for electronic devices that emitted particular beeps and whistles at particular frequencies and could allow free longdistance phone calls. Cool! One time the two called the Vatican and pretended that Wozniak was Henry Kissinger; they claimed to have actually persuaded someone there to wake the Pope up in the middle of the night.

In the Sheff profile, Jobs recalls somehow wistfully, “Woz and I are different in most ways, but there are some ways in which we’re the same, and we’re very close in those ways. We’re sort of like two planets in their own orbits that every so often intersect. It wasn’t just computers, either. Woz and I very much liked Bob Dylan’s poetry, and we spent a lot of time thinking about a lot of that stuff. This was California. You could get LSD fresh made from Stanford. You could sleep on the beach at night with your girlfriend. California has a sense of experimentation and a sense of openness—openness to new possibilities.”

By contrast, Jobs also explains that in most companies personal creativity and innovation is discouraged with the result that “great people leave and you end up with mediocrity. . . . I know,” he tells Sheff, because “that’s how Apple was built . . . Apple is built on refugees from other companies. These are the extremely bright individual contributors who were troublemakers at other companies.”

Economics, being a rather conservative affair, has traditionally downplayed the role of the idiosyncratic entrepreneur in business success—and instead focused on abstract, impersonal models. Only a handful of contrarians, such as Joseph Schumpeter and Israel Kirzner, have been left to argue for the importance of the personal element in entrepreneurship. Nevertheless, recently psychologists like Martin Seligman have identified in the entrepreneur’s mindset several key ingredients: autonomy, selfdirectedness, and creative exploration.

So far, so conventional, and few would argue against such ingredients anyway. But Jobs, unlike most computer nerds, went a step further because he always managed to stay a bit “cool.” And to make sense of Jobs, more important than sensible stuff about “self-directedness” is to understand that part of the Apple difference is his interest in Eastern mysticism. This, he told Sheff, “hit the shores at about the same time.” About the same time as what, you may ask? As Bob Dylan. For Jobs, in both sources, “there was a constant flow of intellectual questioning about the truth of life.”

Dylan could be appreciated via open-air concerts or maybe just recordings, but serious mysticism was imbibed via books. Jobs recalls too that when he was briefly a college student at Reed College, an elite liberal arts school in Portland, Oregon, he started doing lots of LSD and reading lots of esoteric texts about spirituality. He says that it was a time when it seemed that everyone was reading Be Here Now or Diet for a Small Planet—two books drawn from a very short list of about ten. “You’d be hard pressed to find those books on too many college campuses today,” he told Sheff. “I’m not saying it’s better or worse; it’s just different—very different.” Referring to a standard text about business practices, he adds, “In Search of Excellence has taken the place of Be Here Now.”

However, during his freshman year at Reed, it was Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Chogyam Trungpa’s Cutting through Spiritual Materialism, and Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi that he first devoured. The last one in particular, a guide to meditation and spirituality that Jobs had first read as a teenager, was a book he came back to and reread many times during his life.

IT was then that Jobs discovered Be Here Now, a guide to meditation and the wonders of psychedelic drugs by Baba Ram Dass, born Richard Alpert. This book advises things like “What we’re seeing ‘out there’ is the projection of where we’re at—the projection of the clingings of our minds” and “My life is a creative act—like a painting, or a concerto.”

“It was profound,” Jobs told Isaacson. “It transformed me and many of my friends.” Notice that word “transformation.” When Geoffrey James, an editor at the website Inc.com, compiled a list of the “12 Books Steve Jobs Wanted You to Read,” what struck him most was that almost all the books were about a single individual overcoming enormous odds and obstacles in order to transform either the world, himself, or both.

For example, Jobs recommends 1984 by George Orwell, the dystopian novel that makes guest appearances in key Apple publicity ads. 1984 is all about one man’s desperate struggle against an all-pervasive state that is committed to controlling people’s thoughts and behaviors. Then there’s that Autobiography of a Yogi, just mentioned. This is a book by one Paramahansa Yogananda, an Indian guru who offers advice drawn from his life experiences, such as, “You may control a mad elephant; You may shut the mouth of the bear and the tiger; Ride the lion and play with the cobra; By alchemy you may learn your livelihood; You may wander through the universe incognito; Make vassals of the gods; be ever youthful; You may walk in water and live in fire; But control of the mind is better and more difficult.”

But, much as Jobs appreciated these books, it was Be Here Now that became his personal bible.

BE HERE NOW

AUTHOR: RAM DASS

PUBLISHED: 1971

Be Here Now, or in slightly longer version Remember, Be Here Now, is a book of new-age philosophy that was written during its author’s journeys in India. The original cover featured a mandala with some esoteric images and the word “Remember” repeated four times.

The book is an account of the personal journey of Richard Alpert, PhD, into Baba Ram Dass, spiritual leader. It is a quasi-philosophical collection of metaphysical, spiritual, and religious aphorisms, accompanied by illustrations that are offered as “the core” of the book, alongside practical advice on yoga and meditation and finally a list of recommended books on spirituality and consciousness. The list is divided into “books to hang out with,” “books to visit with now & then,” and “books it’s useful to have met.”

Don Lattin’s 2010 retrospective on the book titled “The Harvard Psychedelic Club” and subtitled “How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil Killed the Fifties and Ushered in a New Age for America,” notes that Beatle John Lennon, no less, wrote the song “Come Together” as a campaign tune for Leary’s “quixotic” race against Ronald Reagan for governor of California. The actual slogan was “Come together, join the party” and was composed as a thank-you after Leary and his wife, Rosemary, traveled to Montreal for John and Yoko’s “bed-in for peace,” on June 1, 1969. This, you see, is how counterculture works, lubricated by LSD sessions and group acid trips. Don Lattin also notes rather sniffily that Alpert was a man whose spiritual side was balanced by a yearning for porn films and junk food.

Not the least extraordinary thing about the book is that it has remained in print since its initial publication and has sold over two million copies.

Steve Jobs even credited this book with getting him to try the hallucinogenic drug LSD, and no wonder as a central theme of the book is how during “a period of experimentation,” Alpert/Baba Ram Dass peeled away each layer of his identity, disassociating from himself as a professor, a social cosmopolite, and lastly, as a physical being. As the book description enthuses, “Fear turned into exaltation upon the realization that at his truest, he was just his inner-self: a luminous being that he could trust indefinitely and love infinitely.”

A key passage runs: “The cosmic humor is that if you desire to move mountains and you continue to purify yourself, ultimately you will arrive at the place where you are able to move mountains. But in order to arrive at this position of power, you will have had to give up being he-who-wanted-to-move-mountains so that you can be he-who-put-the-mountain-there-in-the-first-place. The humor is that finally when you have the power to move the mountain, you are the person who placed it there—so there the mountain stays.”

Drugs and existentialism go together like bacon and eggs, or maybe computers and graphics. Over in France, philosophy’s favorite existentialist couple, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who I’ll say a bit more about in a moment, also famously experimented with LSD-type substances. Unfortunately for Sartre, one “bad trip” with mescaline left him with a lifelong fear of crabs, lobsters, and jellyfish, which he would see everywhere, following him in the street, sitting on his desk, even waiting for him in his bedroom. De Beauvoir only says she smoked a little marijuana in New York, and the main effect she found was that it upset her throat. But put aside practical matters: the thread running through all these experiments is a search for your real self. This is the heart of Be Here Now, and Ram Dass sums up the existentialist message very well when he writes, “Only when I know who I am will I know what is possible.” No wonder that the book has been described as a “countercultural bible.”

What qualifies someone to write such a thing? Nothing too formal. In the case of Ram Dass, while he was still plain old Richard Alpert, he had worked for a while at Harvard University conducting research on psychedelic drugs—that is, until he was rather abruptly dismissed for, ahem, “breaking university rules.” Let’s not go into that. Anyway, it was shortly after this that he went to India, met another American spiritual seeker called Kermit Michael Riggs (I’m not making this up), and renamed himself “Ram Dass,” which means “servant of God.”

The deeper the Self-realization of a man, the more he influences the whole universe by his subtle spiritual vibrations, and the less he himself is affected by the phenomenal flux.

“Why be elated by material profit?” Father replied. “The one who pursues a goal of even-mindedness is neither jubilant with gain nor depressed by loss. He knows that man arrives penniless in this world, and departs without a single rupee.”

The same sentiment reappears, unmistakably, in the Stanford Commencement Address, delivered by Jobs not, of course, in the capacity of an academic professor or even religious guru but instead—better!—as a fabulously successful CEO: “Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven’t found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle. As with all matters of the heart, you’ll know when you find it. And, like any great relationship, it just gets better and better as the years roll on. So keep looking until you find it. Don’t settle.”

Following his own early departure from academia (in fact, his “alternative reading list” is about all that Steve got out of college), Jobs decided, like many young people before and since, that he wanted to travel the world. However, the young Steve realized he had to make some money first. So, on his own account, he opened up the paper, saw a job advert that said, yes, “Have fun and make money,” and called. It was Atari. “I had never had a job before other than the one when I was a kid. By some stroke of luck, they called me up the next day and hired me.”

In this way, his unerring feel for the “right time, and right place” skill got Jobs his first “real job” too. Atari was just starting up then, and Jobs was employee number forty. It was a very small company that made Pong (based on tennis) and a couple of less successful games. His first project was helping a guy named Don work on a basketball game project, which was a disaster. Then there was a baseball game, and somebody else was working on a hockey game. They flopped too. But now Jobs thought that he could see why. The programmers hadn’t managed to penetrate to the essence of what made the sports compelling in the first place. As he put it later in that revealing interview with Sheff, a special quality of the original video game, Pong, was that it “captured the principles of gravity, angular momentum and things like that, to where each game obeyed those underlying principles, and yet every game was different—sort of like life. That’s the simplest example. And what computer programming can do is to capture the underlying principles, the underlying essence, and then facilitate thousands of experiences based on that perception of the underlying principles.”

Anyway, while at Atari, Jobs was allowed to work at the firm in the evenings, and he used to let Woz in, largely to play the early computer games. His boss, the CEO, Nolan Bushnell, knew about this but considered it a good arrangement because “Woz was a savant, no question about it” and in this way he got “two Steves for the price of one” to build his arcade game.

One project that particularly attracted Woz was called Gran Trak. It was the first car racing game with an actual steering wheel to drive it, and Woz soon became something of a Gran Track addict. He would play it all night long while Steve was wrestling with code, but if Steve came up against a stumbling block on a project, he would get Woz to “take a break from his road rally for ten minutes” and come and help. In this informal process lay the seeds of the technical collaboration that created the Apple I computer.

So what if some Californian dudes were going to make a new kind of computer? But remember that this was a time long before computers were consumer goods, long before things like iPhones could even be dreamed of. The Apple I was just a printed circuit board. There was no case; you had to buy your own keyboard. There wasn’t even a power supply, as no transformer was included.

Even so, the big step of manufacturing and selling them to make money was serious stuff. It required Jobs to sell his VW bus and Woz his Hewlett Packard calculator to finance the initial batch of Apple Is. A friend who owned one of the first computer stores provided their only retail outlet. They sold only about 150 of the very first Apple I computers—ever—but even so, as Jobs told Playboy, “We made about $95,000 and I started to see it as a business besides something to do.”

And Jobs was now interested in the mysteries of how to build a company. The two Steves’ next venture, the Apple II, was a game changer, aimed at people who didn’t have to be hardware hobbyists but instead just wanted to play with a computer. The first year, 1976, they sold three or four thousand—representing about $200,000—all while the factory was literally still the garage. And a year later they had about $7 million in sales. As Jobs says, the interest and sales were “phenomenal”! In 1978, they sold $17 million worth. In 1979, $47 million. By 1980, it was $117 million, and a year later, $335 million. In 1982, it was half a billion dollars. A year later, they had a billion-dollar company.

That’s the business story, and it is a wonderful tale in itself. But behind the business success lies that existential aesthetic. One of the best questions that David Sheff puts to Jobs is what does he think is “the difference between the people who have insanely great ideas and the people who pull off those insanely great ideas”? Jobs replies by comparing the Apple approach with that of IBM, saying, “How come the Mac group produced Mac and the people at IBM produced the PCjr? We think the Mac will sell zillions, but we didn’t build Mac for anybody else. We built it for ourselves. We were the group of people who were going to judge whether it was great or not. We weren’t going to go out and do market research. We just wanted to build the best thing we could build” (emphasis added).

Here is existentialism applied to manufacturing. Designing computers based on market research is like being a waiter taking orders in a French bar. That was not going to be Jobs’s approach. Because for Jobs, every product has its own essence, its own rationale, and all other considerations are secondary. It’s a daring line to follow in a competitive marketplace. But Jobs made the approach work in two world-beating companies—both at Apple and again at his film animation company, Pixar. Jobs gives a very clear account of his commitment, to use another key existentialist term, toward “thinking differently” when (again in the Playboy interview) he recalls a classic tale about Bell Telephones:

A hundred years ago, if somebody had asked Alexander Graham Bell, “What are you going to be able to do with a telephone?” he wouldn’t have been able to tell him the ways the telephone would affect the world. He didn’t know that people would use the telephone to call up and find out what movies were playing that night or to order some groceries or call a relative on the other side of the globe. But remember that first the public telegraph was inaugurated, in 1844. It was an amazing breakthrough in communications. You could actually send messages from New York to San Francisco in an afternoon. People talked about putting a telegraph on every desk in America to improve productivity. But it wouldn’t have worked. It required that people learn this whole sequence of strange incantations, Morse code, dots and dashes, to use the telegraph. It took about 40 hours to learn. The majority of people would never learn how to use it. So, fortunately, in the 1870s, Bell filed the patents for the telephone. It performed basically the same function as the telegraph, but people already knew how to use it. Also, the neatest thing about it was that besides allowing you to communicate with just words, it allowed you to sing. [Emphasis added again.]

“Allows you to sing” is a phrase that Jobs would often drop into descriptions of his computers. People often misinterpret the reference. However, in the 1985 interview, he is very clear about what he means:

It allowed you to intone your words with meaning beyond the simple linguistics. And we’re in the same situation today. Some people are saying that we ought to put an IBM PC on every desk in America to improve productivity. It won’t work. The special incantations you have to learn this time are “slash q-zs” and things like that. The manual for WordStar, the most popular word-processing program, is 400 pages thick. To write a novel, you have to read a novel—one that reads like a mystery to most people. They’re not going to learn slash q-z any more than they’re going to learn Morse code. That is what Macintosh is all about. It’s the first “telephone” of our industry. And, besides that, the neatest thing about it, to me, is that the Macintosh lets you sing the way the telephone did. You don’t simply communicate words, you have special print styles and the ability to draw and add pictures to express yourself.

For Jobs, great businesses are built up out of the bricks of intellectual playfulness, research, experimentation, analysis, and judgment. But of all of these, it’s intellectual playfulness that is the most important. As one venture capitalist once put it, “Money does not get the ideas flowing. It’s ideas that get the money flowing.”

Jobs managed to “get the ideas flowing” because he eschewed unthinking acceptance of the views of others, what the right-wing novelist and many CEOs’ favorite philosopher Ayn Rand called “second-handedness.” Instead, Jobs embraced “first-handedness,” or independent thinking with a Platonic orientation not toward others’ opinions but toward reality, or at least “reality” as you see it. “Don’t be trapped by dogma—which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice,” he advises. In true existentialist style, he continues, “To [do] something really well, you have to get it. You have to really grok what it’s all about. It takes a passionate commitment to really thoroughly understand something, chew it up, not just quickly swallow it. Most people don’t take the time to do that.”

Or put short: think different. He then adds, “I think one of the potentials of the computer is to somehow . . . capture the fundamental, underlying principles of an experience.”

In a YouTube short called “Steve Jobs Philosophy on Life,” he says,

Life can be much broader, once you discover one simple fact, and that is that everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it, you can build your own things that other people can use. And the minute that you understand that you can poke life and actually something will, you know if you push in, something will pop out the other side, that you can change it, you can mold it. That’s maybe the most important thing. It’s to shake off this erroneous notion that life is there and you’re just gonna live in it, versus embrace it, change it, improve it, make your mark upon it. . . . Once you learn that, you’ll never be the same again.

The quest to identify the key working principles of life and then apply them to work in your own way is a profoundly philosophical, existentialist project. So let’s say a bit more about the philosophy itself.

Existentialism is a philosophy of action, an “ethic of action and selfcommitment,” as one of its best-known exponents, Jean-Paul Sartre, said in 1946, just after passing World War II eating boiled turnips in Paris and writing philosophy.

Actually, Sartre emphasizes what is not over what is, the latter being a rather humdrum sort of affair consisting of the kind of things that scientists, and no doubt computer programmers, examine, while the “what is not” is really much more interesting. He sums up his view (if “sums up” is ever an appropriate term in existentialist writing) thus: “The Nature of consciousness simultaneously is to be what is not and not to be what it is.” And hence we come back to our own natures, our own “essences.” We exist, yes, but how do we define ourselves? Or, in one of the movement’s catchphrases, “existence precedes essence.”

It is here that Sartre’s most celebrated example, that of a waiter (or “server”), comes in:

His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid. He comes toward the patrons with a step a little too quick. He bends forward a little too eagerly; his voice, his eyes express an interest a little too solicitous for the order of the customer. Finally there he returns, trying to imitate in his walk the inflexible stiffness of some kind of automaton while carrying his tray with the recklessness of a tight-rope walker by putting it in a perpetually unstable, perpetually broken equilibrium which he perpetually re-estab-lishes by a light movement of the hand and arm. (Being and Nothingness, 1943)

Sartre seems to have had a prejudice against waiters, in fact. He saw them in the same sour light that Plato saw actors, as somehow presenting a fake, false face to the world. His example belies the very function of a waiter and dismisses them with a lofty disdain that really has more to do with his privileged roots than any real philosophy. And yet, as a metaphor, it can be allowed. The waiter is performing a role that is not “authentically” theirs. When they say that the chicken fricassee is excellent today, we cannot be entirely sure whether that is really their opinion at all.

Elsewhere, Sartre’s existentialism emphasizes the use of imagination, which is the purest form of freedom available to us. In a tome called Critique of Dialectical Reason, Sartre offers by way of example workers engaged in monotonous tasks yet having sexual fantasies, thus demonstrating the power and counterfactual freedom of the imagination. Sartre was no businessperson; indeed, he rather looked down on “all that” or adopted a radical political stance on public ownership.

Of course, most Apple employees humbly employed in the factories have no chance to use much imagination, but at Apple’s Californian HQ, and even more clearly at Pixar, imagination was put center stage. No wonder Jobs once described being fired from Apple as “the best thing that could have happened because the heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again . . . it freed me to be creative again.”

It was in 1986, shortly after he was forced out of Apple Computer in a boardroom battle over management policy, that Steve Jobs bought the small computer manufacturer named Pixar from George Lucas, the director of Star Wars. By 1990, he was supporting the company out of his own pocket as project after project died. “We should have failed,” Alvy Ray Smith, a cofounder of Pixar, says in David Price’s The Pixar Touch. “But it seemed to me that Steve would just not suffer a defeat. He couldn’t sustain it.” The survival of Pixar, and its subsequent rise, is a revealing case study in Jobs’s approach to innovation. Although his background was in computer hardware, he helped transform Pixar into one of the most successful studios in the history of cinema.

In November 2000, Jobs purchased an abandoned Del Monte canning factory to be Pixar’s base. The original architectural plan called for three buildings: separate offices for the computer scientists, the animators, and the Pixar executives. Logical. Jobs immediately scrapped it. Instead of three buildings, there was going to be a single vast space with an airy atrium at its center. “The philosophy behind this design is that it’s good to put the most important function at the heart of the building,” Catmull says. “Well, what’s our most important function? It’s the interaction of our employees. That’s why Steve put a big empty space there. He wanted to create an open area for people to always be talking to each other.”

Jobs realized, however, that it wasn’t enough to simply create a space; he needed to make people go there to force computer geeks and cartoonists to mix. In typical fashion, Jobs saw this as a design problem. He began with the mailboxes, which he shifted to the atrium. Then he moved the meeting rooms to the center of the building, followed by the cafeteria, the coffee bar, and the gift shop.

For years, though, Pixar’s model of digitally animated movies lost money and was kept afloat primarily because Jobs believed in it and continued to fund it. Indeed, it seemed he simply couldn’t stomach admitting failure. But, long after all sensible accountants would have pulled the plug, the magic worked. Following the 1995 release of Toy Story, every film Pixar created and released has been a commercial success, with an average international gross of more than $550 million per film.

Later on, the creativity regained at Pixar also led to a remarkable rebirth at Apple when Jobs returned to the by then ailing company. Soon, the iPhone, iTunes, and iPad all became remarkable commercial successes. And all the time Jobs followed his laid-back variety of existentialist philosophy:

Don’t take it all too seriously. If you want to live your life in a creative way, as an artist, you have to not look back too much. You have to be willing to take whatever you’ve done and whoever you were and throw them away. What are we, anyway? Most of what we think we are is just a collection of likes and dislikes, habits, patterns.

At the core of what we are is our values, and what decisions and actions we make reflect those values.

As you are growing and changing, the more the outside world tries to reinforce an image of you that it thinks you are, the harder it is to continue to be an artist, which is why a lot of times, artists have to go, “Bye. I have to go. I’m going crazy and I’m getting out of here.”

Introducing the iPad 2 in March 2011, Jobs summarized his strategy this way: “It is in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough—it’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our heart sing.”

The existentialist refusal to be pigeonholed into being either “a scientist” or “an artist” allowed Jobs to make Apple’s technology beautiful. Revealingly, Jobs’s biography notes that even after he dropped out of Reed College during his freshman year, he continued to take classes in calligraphy: “I learned about serif and sans-serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating. None of this had even a hope of practical application in my life. But ten years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me.”

It’s said that Jobs even had the engineers’ names engraved inside each one. Why? Because “real artists sign their work.” Contrast all this with the West Coast Computer Fair in April 1981. There, Adam Osborne released what he described as the first truly portable personal computer. It had only a five-inch screen and hardly any memory, but it worked after a fashion. Osborne announced, “Adequacy is sufficient. All else is superfluous.” Jobs was appalled at this and for days told everyone he met that Osborne was a guy who just didn’t “get it.” “He’s not making art, he’s making shit.”

It is revealing that even as a millionaire, Steve’s house had almost no furniture in it—just a picture of Einstein, whom he admired greatly, a Tiffany lamp, a chair, and a bed. He didn’t believe in having lots of things around, and he was incredibly careful in what he selected. When he returned to Apple in 1997, he took a company with 350 products and in two years reduced them to just ten. But then Jobs, talking about change and obsolescence, once said, “I think death is the most wonderful invention of life.”

Speaking about life and death, which existentialists invariably come back to, there’s a very revealing story about Jobs that also helps explain why he was so extraordinarily successful in turning Apple into one of the world’s most iconic companies. One time he challenged an engineer called Larry Kenyon as to why the operating system took so long to boot up. (We’ve all stared aimlessly at blank screens wondering much the same thing.) Kenyon started a long, technical explanation that Jobs brusquely cut off. “Larry, if it could save a person’s life, would you find a way to shave ten seconds off the boot time?” Kenyon conceded that he might, hardly expecting much to follow from that concession.

And now here comes the impressive bit. Jobs went over to the whiteboard in the engineer’s office, grabbed a marker, and showed that since there were at least five million people who used Macintosh computers, if it took ten seconds extra to turn them on every day, then the amount of time being lost was equivalent to one hundred lifetimes—per year! A few weeks later, Larry Kenyon had found a way to save not a mere ten seconds but nearly half a minute off the boot-up time.

Of course, Steve didn’t really think that computers that were slow to boot cost lives. After all, people could be rearranging their paper clips or something while the cursor was spinning. In fact, his concern was not practical at all. He wasn’t interested in the current limitations of the technology or in winning a race with competing computers—far less in making a lot of money. Instead, his goal was to do something the best way imaginable.

Jobs was convinced that for an object to be truly great, it had to be completely “authentic,” meaning true to its own origins and purpose. He abhorred the idea of compromises and “compatibility.” It is said that he even designed the original Macintosh computers to have no cursor arrow keys—partly as a way of forcing people to use the mouse to click and point and partly to oblige software designers to use a more visual approach in the design of their programs. But user choice didn’t come into it. The right approach would be forced on them whatever their inclinations.

And part of the deal was that market share was thrown away in order to produce Macs running the Mac operating system and Mac programs. Because anything else, as ZDNet’s founder, Dan Farber, put it to Jobs’s biographer, Isaacson, would have been like inviting the local decorator to add some brush strokes to a Picasso painting. Okay, that’s an analogy, but the fact that Jobs really saw the world like this is borne out by the time he took a team from Apple to see an exhibit of Tiffany glass in San Francisco. For Jobs, the exhibition was important as it showed that something mass-produced could also be great art. Great art? Computers? But yes: “Here’s to the crazy ones . . . because they change the world.”

Most CEOs aren’t crazy at all, though. They’re very careful types who start with a hardheaded strategy and then at most adapt it in the light of any highfalutin, quasi-philosophical comments received. Not so Apple’s visionary, Steve Jobs. He started off with a philosophy of life melded from personal experiences and a countercultural bible rooted in existentialism and then shaped his business strategy around that. Actually, to me, it still seems remarkable that something as precise and, well, technical as a computer interface could have its roots in a hippy philosophy. But maybe the weirdness of this is made more understandable when you recall the case of another great computer pioneer who was working just a decade earlier also in the United States. This is Evelyn Berezin, who found inspiration in the alternative universes of science fiction and “amazing” stories, and her own is pretty “amazing” too.

The first Apple was launched into the world in 1978. However, it was only able to do so because a decade earlier, which in computer terms is ancient history, Evelyn Berezin (pronounced “bear-a-zen”) had not only set up the Redactron Corporation, a tech start-up on Long Island that was the first company exclusively engaged in manufacturing computerized typewriters, but also invented new kinds of technology able to control them.

Berezin was every bit as much of a pioneer as Jobs and Wozniak. At a time when computers were in their infancy and few women were involved in their development, her machines were bulky, slow, and noisy, but they could edit, delete, and cut and paste text. To some offices, particularly those producing standard letters with small amounts of individual content, Redactron word processors arrived “like a trunk of magic tricks” as the New York Times put it in its 2018 tribute to Berezin.

Redactron enthusiastically christened its computer “the Data Secretary.” Early versions looked like an upright black refrigerator; input and output were both via an IBM Selectric Typewriter with a rattling golf ball printhead, and there was as yet not even a rudimentary screen for words to trickle across. And yet underneath the bland, office equipment surface was something quite revolutionary: thirteen semiconductor chips, some of which Berezin had herself designed, and a system of programmable logic patiently waiting to deliver its word-processing functions.

During the early 1970s, Redactron sold some ten thousand machines for $8,000 each. If you think that’s a bit steep for a word processor, bear in mind that in today’s money it is actually about $53,312—and four cents. No wonder her chief competitor, International Business Machines (IBM), didn’t sell its devices but instead only rented them out. However, beyond that, IBM machines relied on electronic relays and tapes, not semiconductor chips, and so were barely in the same technological era. By 1975, Redactron had made $20 million from its word processor, or again, about seven times that at today’s prices. Certainly, this was an extraordinary achievement, and doubly so, for the child of a family of barely literate refugee parents.

Of course, “Big Blue” (IBM) soon caught up technologically and later in the decade swamped the market, pursued by a herd of new brands, like Osborne, Wang, Tandy, and Kaypro. However, as the Times put it, for a few heady years, “Ms. Berezin was a lioness of the young tech industry, featured in magazine and news articles as an adventurous do-it-herself polymath with the logical mind of an engineer, the curiosity of an inventor and the entrepreneurial skills of a C.E.O.”

Her pioneering work included designing logic boards and inventing new kinds of computer-to-computer communication, vital groundwork for the later Internet age. “Why is this woman not famous?” the British writer and entrepreneur Gwyn Headley asked in a 2010 blog post for a site called Fotolibrarian. “Without Ms. Berezin,” he continued enthusiastically, “there would be no Bill Gates, no Steve Jobs, no internet, no word processors, no spreadsheets; nothing that remotely connects business with the 21st century.”

Actually, that’s overstating Berezin’s role and significance and misunderstanding the collective nature of the advance of computers. Yet, curiously, in as much as technological breakthroughs depend on particular individuals, the same should be said of a cluster of science-fiction writers, because without their short stories in a pulp magazine called Astounding Science-Fiction, Evelyn Berezin would never have been tempted to become a computer scientist, there would have been no Redactron, and the arrival of the modern computer would have taken substantially longer.

I say that because even if today her name is not familiar to many, nonetheless Evelyn Berezin is truly one of a tiny group of people who made the modern world, and in her case it seems clear that she was inspired to take her then unheard of career path by reading science-fiction stories in a magazine.

In fact, many of the most famous names of the genre explored cutting-edge scientific ideas in short stories as well as later on in full-length novels, these being published in the 1930s and onward. One such was Georgiy Gamov (also known as plain George Gamow), a respected physicist who had moved from Russia to the West, where he became involved in the development of quantum theory alongside iconic figures like Niels Bohr and Ernest Rutherford. Gamov also became one of the most ardent proselytizers for the now standard but then controversial theory of the universe’s origins, known as the Big Bang theory, in opposition to the then widely accepted steady-state universe theory. This had been popularized by his friend and fellow keen science-fiction writer Fred Hoyle, whose own book The Black Cloud (1957) is considered something of a sci-fi classic.

Actually, Gamov’s stories, featuring Mr. Tompkins, such as Mr. Tompkins in Wonderland (1939) and Mr. Tompkins Explores the Atom (1944), are rather less celebrated yet still explore the wonders of science, including relativistic effects like that which would astonish the young Evelyn Berezin. The first lines of Mr. Tompkins in Wonderland run,

It was a bank holiday, and Mr. Tompkins, the little clerk of a big city bank, slept late and had a leisurely breakfast. Trying to plan his day, he first thought about going to some afternoon movie and, opening the morning paper, turned to the entertainment page. But none of the films looked attractive to him. He detested all this Hollywood stuff, with infinite romances between popular stars. If only there were at least one film with some real adventure, something unusual and maybe even fantastic about it. But there was none. Unexpectedly, his eye fell on a little notice in the corner of the page. The local university was announcing a series of lectures on the problems of modern physics, and this afternoon’s lecture was to be about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. Well, that might be something!

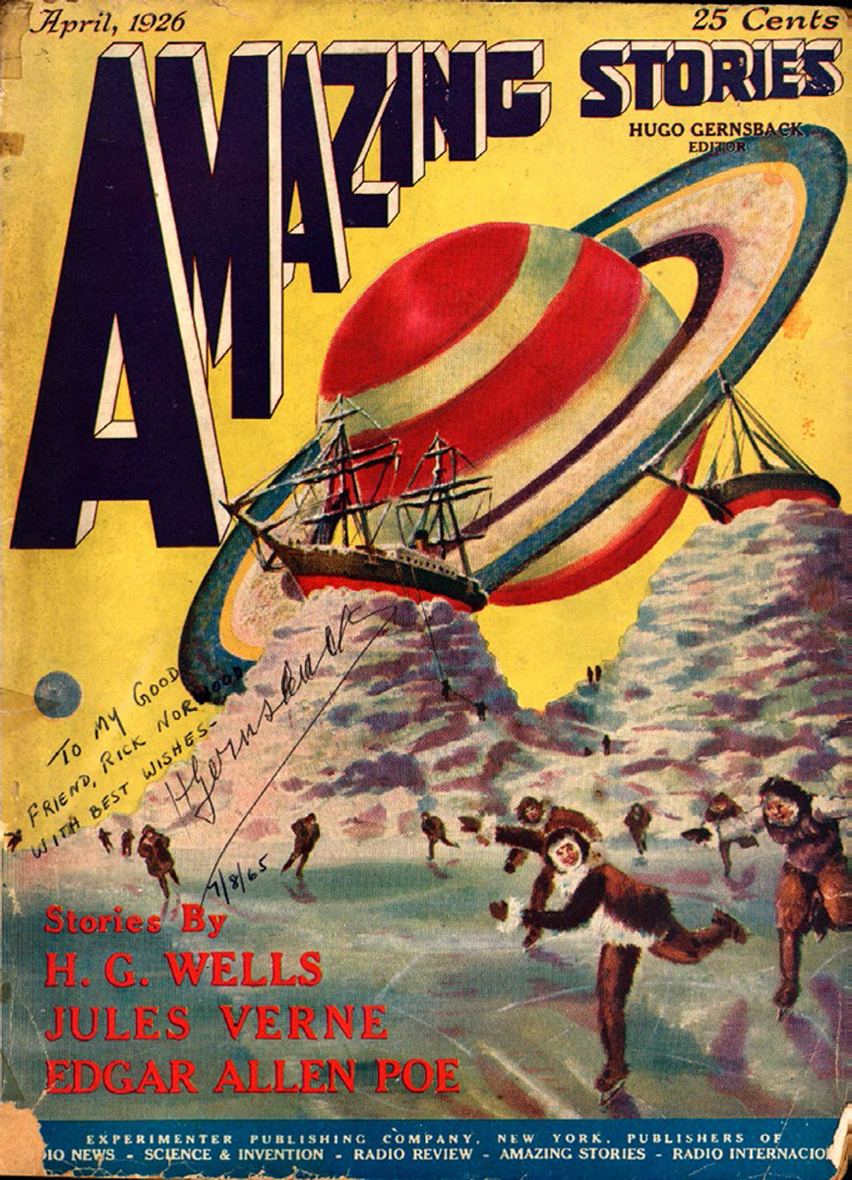

First issue of Amazing Stories, cover art by Frank R. Paul. This copy was autographed by Gernsback, the publisher. (Amazing Stories, Vol. 1, No. 1. Gernsback, Hugo, “Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming.” Internet Archive. Experimenter Publishing Co., April 1, 1926. https://archive.org/details/AmazingStoriesVolume01Number01/mode/2up.)

To which might be said, don’t besiege the bookshops; there’s plenty of copies to go round. Nonetheless, James Watson, one of the scientists who helped pin down the hidden workings of life via his discoveries of the famous double-helix structure of DNA, pays tribute to the great importance of Gamow’s insightful contributions to many scientific debates in his autobiographical book Genes, Girls, and Gamow: After the Double Helix (2001)—insights perhaps like that in The Creation of the Universe (1952), where Gamow says, “It took less than an hour to make the atoms, a few hundred million years to make the stars and planets, but five billion years to make man!”

ASTOUNDING SCIENCE-FICTION

AUTHOR: VARIOUS

PUBLISHED: SINCE 1930

Astounding was a magazine launched in 1926 by inventor-writer Hugo Gernsback’s Experimenter Publishing. It was published under various titles, including Astounding Science-Fiction and Astounding Stories of Super-Science, and by providing an outlet for a new breed of writers is credited with spawning an entirely new genre in the publishing industry. Over the years, many of the most famous names of science fiction appeared in its columns.

A. E. van Vogt’s classic work Rogue Ship (1965) includes elements from a short story originally published in Astounding Science-Fiction featuring the kinds of relativistic effects that intrigued Berezin. In the book, a spaceship manages to exceed the speed of light. It returns to Earth on a collision course, but instead of being smashed to smithereens on impact, it burrows into the ground, barrels straight through, and reemerges unscathed! This, all thanks to those relativistic effects. The ship’s owner, who had sent it on its way six years earlier, forces his way inside the spaceship, where he finds time slowed down to a near standstill and everything, people included, severely compressed in the direction of travel.

“Certainly, science fiction requires you, in Steve Jobs’ phrase, to ‘think different.’”

If college drop-out and lifelong hippy Steve Jobs makes an unlikely candidate for a twentieth-century computer scientist, Berezin’s background isn’t the obvious one either. Her parents were refugees from Russia who arrived and settled in New York at the start of the twentieth century as part of a Jewish exodus. Evelyn would be born in poverty in the Bronx in 1925, with two brothers, seven and five years older respectively. Her father was a furrier, and neither parent could read or write English, nor were they much better in any other languages. He worked thirteen hours a day, six days a week, which was the standard experience of workers of the time.

At her junior school, called rather grimly Public School 6, Evelyn had to walk in a line determined by height. Every week included a test. School 6 was not a place where creativity was encouraged. However, being hardworking and precocious, by age fifteen she had progressed to a newly opened high school called Christopher Columbus. This school was as exciting and innovative as the previous one was dull and traditional. And it was here that her interest in science and things technical grew to become her lifelong passion. The United States was still in the grip of the Great Depression, and jobs were hard to find; in this new school, her math teacher had a PhD from Princeton, and her physics teacher had a PhD from Chicago. And they were both young. The teachers were close to the students and set up laboratories for students to freely try things out. Evelyn would stay after school experimenting as if in a deluxe toy shop. For her, schools and the local library were the best places to be, as she recalled later.

But the spark that set her on the path that in due course would lead her to invent the first word processor and design the first digital booking system—which never crashed, not once—came not from school but from those short stories of science fiction.

When Evelyn was very young, she had read things like fairy tales, but she became fascinated by the alternative universes she discovered when her elder brother started buying a magazine called Astounding Science. Talking about her early influences as part of an oral history project on computers, she said, “I was fascinated by it, I thought it was marvelous. I used to steal them from him all the time. It was really the thing that got me interested in this.”

In an extended interview on March 10, 2014, recorded in New York at her home, she went on to explain to the researcher Gardner Hendrie how, when she was only seven, she “started looking at these things” and how much of an impression they had made. “I wanted to study physics from the time I read about in Astounding Science.” This was all the more remarkable as, at the time she was studying, girls just weren’t supposed to do science. Indeed, she was often obliged to study other things.

One incident she describes is revealing. She went up to her science teacher in junior high and asked him about something she had read in the magazine. The question was about how when something goes very fast, near the speed of light, the object shrinks in size in the direction of travel. The teacher had said, “Oh no, that’s impossible, they’re making it up.” As she recalled to Hendrie, “And I never forgot that, because I believed him.”

Now, although “length contraction,” as it is known, is a fairly well-established element of relativity theory, which dates from the early years of the twentieth century, perhaps the teacher can be forgiven this assumption, partly because the magazine was originally titled Astounding Stories of Super-Science, before being shortened to the dodgy sounding Astounding Stories and finally becoming Astounding Science-Fiction in 1938 under its new editor, George Campbell. However, Berezin’s remembering it as Astounding Science is understandable. Campbell asked his writers to write stories that felt as though they could have been published as factual science stories in a magazine of the future; he also included regular nonfiction pieces with the goal of stimulating ideas. Berezin again: “In one of these Astounding Science articles, a lot of which used real physics—they were imaginative and all things but they actually had real science in them.”

For SF aficionados, the period beginning with Campbell’s editorship of Astounding is the golden age, and certainly the magazine had immense influence on the genre. Within two years, alongside pieces by established authors like L. Ron Hubbard, Clifford Simak, Jack Williamson, L. Sprague de Camp, Henry Kuttner, and C. L. Moore, all regulars in either Astounding or its sister magazine, Unknown, Campbell had published stories by new writers who would become iconic figures in the genre, including Lester del Rey, Theodore Sturgeon, Isaac Asimov, A. E. van Vogt, and Robert Heinlein. For these, publication in the magazine was a literary launchpad, just as for readers, like the young Berezin, their ideas were lifelong inspirations.

It is no coincidence that Asimov, Heinlein, and de Camp were all trained scientists and engineers because Campbell’s cultivation of this new genre of writing emphasized scientific accuracy—sometimes even over literary style. And if her first teacher had poured cold water on the stories, more support came for the pulp science magazine when she moved up to high school and asked the physics teacher there about the same scientific claims. Now she found out that this first science teacher had told her something wrong indeed, “really wrong,” as she still put it even so many years later.

Actually, to be fair to the offending teacher, although it was Einstein’s work that was in those days popularizing the idea of relativistic effects, the Astounding article was specifically talking about the theories of George Fitzgerald, offered as part of a nineteenth-century debate about the speed of light and whether or not it traveled through an invisible ether. So maybe “really wrong” is a bit unkind to the school’s science teacher, who was presumably trying to arbitrate on this older scientific debate.

Either way, though, it did reveal to the young Evelyn the extraordinary access to cutting-edge ideas that the written word, in this case a two-dime magazine, can bring. “I was just dumbstruck by the idea that a teacher can be wrong,” she recalled to Hendrie seventy years later.

Anyway, we shouldn’t come down too hard on teachers because if one almost put Berezin off her destiny as a computer scientist, it was another who directly encouraged and even facilitated it. A very practical reason why she managed to follow her unlikely dream was that one day her high school teacher turned up at her home and told her about an opportunity at a new company called International Printing Ink. As her teacher explained that day, the company had its own research labs and would finance her future studies. Actually, part of the reason that the opportunity arose was because, at this time, the opening years of World War II, Evelyn Berezin’s being female was actually an advantage as young men were subject to the call up for the army.

Other times, though, being female worked against her. Applying for a job to design a new computer system for the New York Stock Exchange, a job that she may well have been the only person in the country capable of implementing, she was turned down on the grounds that the work would have required her to mix with the traders on the floor and thus to have been exposed to “bad language.” Of course this patronizing attitude really concealed a determination to protect a male bastion from infiltration by the fair sex. Talking to Hendrie for the history project, Berezin offers a characteristically wry footnote to that unfair decision, describing how the job that she eventually ended up taking involved supervising an early computer constructed out of hundreds if not thousands of vacuum tubes, technology that generated at the best of times enormous amounts of surplus heat. In the summer the building she worked in with her male engineering team reached temperatures of 100º Fahrenheit, and the men were in the habit of stripping down to nothing but a sort of apron that prominently displayed their buttocks. Her job required her to mix with them as if nothing was remarkable in the slightest. Which is, of course, exactly what she did.