8

Make a Huge Profit—and Then Share It

Most of the books here so far have been either fiction or broad-brush factual works, particularly philosophical ones. The readers I’ve described seem to have chanced upon ideas in them that either captivated or inspired them and sent them off on a new line of thinking.

But of course there’s another kind of reader who has a pretty precise idea already of what they want, and this kind looks through the library shelves for books on precisely that. They’re not in search of new ideas as such but rather are looking for facts, methods, and details. If fictional works attract the gushing reviews in the Sunday papers, the grand prizes, and the excited media chatter, it is in more workmanlike volumes in reference libraries that many readers first found a crucial guide, a fellow spirit that would channel their intuitions and shape their destiny.

The American stock market guru Warren Buffett is just such a case in point. Here is a man who seems to have always had a pretty precise idea of what he wanted to do and achieve in life (essentially following in his father’s footsteps) and, as a young man, had already taken certain career steps to effect that. Yet of all the people I looked at while researching this book, Buffett is the one to most firmly declare that books shaped his life.

We already saw a little bit of this conviction in the introduction, where I recalled him pointing at a pile of books in his office and offering as advice to entrepreneurs of all kinds that they read “500 pages like this every day.” Five hundred pages! This directive turns books into a kind of raw material that might be dug out of the ground and sold on the stock exchanges that Buffett’s life revolves around. Plus, to me, it’s absurd to imagine that plowing through pages and pages of texts chosen like this will give you anything other than tired eyes and maybe a headache. But of course that’s not what Buffett is really urging. I think that he is more likely saying that time invested (and “investments” is the word that defines this man) in reading is well spent because books are like brain multipliers. It might take you a decade to match an author for background knowledge in their chosen field; how much smarter to just read their books and let them share their insights.

NONFICTION FAVORITES OF CEOS

Warren Buffett’s advice to anyone who wants to become a successful entrepreneur can be summed up in three words: read a lot. And here are the favorite books of three such businesspeople who seem to think the same thing.

First of all, consider Narayana Murthy, the Indian cofounder of Infosys, who has been listed as one of the twelve greatest entrepreneurs of our time by Fortune magazine. (Infosys is a global brand specializing in cutting-edge digital services.) Murthy has never shied away from sharing his love for reading. Like Buffett, his favorite book is a practical guide directly relevant to his work—in his case, Jon M. Huntsman’s story of how he built a $12 billion company from scratch. The book is called Winners Never Cheat Even in Difficult Times, and its core message is that although it can sometimes seem tempting to take shortcuts to get to the top, it is always best to build your company with integrity, and doubly so when times get tough.

Then there’s Bill Gates, cofounder of Microsoft and one of Buffett’s personal friends. Indeed, Gates shares with Buffett many things, the most superficial being that he is fabulously rich, but a second being that he is a dedicated philanthropist who seeks to use his wealth for the benefit of humankind. The third similarity is a real love of books. As discussed in the introduction, Gates recommends many authors from different genres, but it seems that in his own case it is really a business book that is his preferred beach read, Business Adventures: Twelve Classic Tales from the World of Wall Street written by John Brooks. The book, which is also one of Buffett’s favorites, seeks to explain why some businesses, like Xerox and General Electric, are successful and why others, like Ford’s Edsel venture, fail. If these twelve tales are given a new spin by the publisher, some reviewers nonetheless saw them as being rather dated tales of corporate life in America.

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg has spoken time and again, though to my mind less convincingly than Gates or Buffett, of his love for books. Perhaps that’s because Zuckerberg names Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty as his favorite book. This joint effort by Armenian American economist Daron Acemoglu and British political scientist James Robinson uses institutional economics, development economics, and economic history to understand why nations develop differently, with some succeeding in the accumulation of power and prosperity and others failing along the way. Zuckerberg, rather sanctimoniously, credits this book with helping him better understand the origins of global poverty.

Warren Edward Buffett (born August 30, 1930; he’s a Virgo, the sign astrologers consider a “natural” fit for investments!) is an American tycoon with a net worth of nearly $90 billion, making him the third-wealthiest person in the world. Buffett is the second of three children and the only son of Congressman Howard Buffett, who was himself an investor with a small private firm. Buffett displayed an interest in business and markets at a young age. How young? When he was just seven, he borrowed a book called One Thousand Ways to Make $1000 from the Omaha Public Library.

Entrepreneurial ventures punctuated much of Buffett’s early childhood years: selling chewing gum, Coca-Cola bottles, golf balls, and magazines door to door. On his first income tax return in 1944, Buffett claimed a thirty-five-dollar deduction for the use of his bicycle and watch on his paper route. In 1945, as a high school sophomore, Buffett and a friend spent twenty-five dollars to purchase a used pinball machine, which they placed in the local barber shop. Within months, they owned several machines in three different barber shops across Omaha. The business was sold later in the year for $1,200.

In high school, he invested in a business his father owned and purchased a forty-acre farm worked by a tenant farmer. He bought the land when he was fourteen years old with $1,200 of his savings. By the time Buffett had finished college, he had already saved up the equivalent of $100,000 today. He might even have become the richest person in the world if he hadn’t also turned out to be splendidly disinterested in money for himself, favoring instead numerous philanthropic ventures.

And so Buffett’s interest in the world of business and investing was well established even as a teenager. In fact, he would have preferred to skip university in order to focus on his business ventures; he only enrolled at university at his father’s insistence. After a spell at Pennsylvania, he transferred to Nebraska, from where he graduated at only nineteen years of age. It was at this point that he happened across a newly published book called The Intelligent Investor by one Benjamin Graham. Buffett liked the book so much he says he read it about half a dozen times. What is more, seeing that Graham taught at the Business School of Columbia University, he made a beeline there to continue his studies after all. In due course, he would not only complete a master of science in economics at Colombia but also develop an investment philosophy rooted in Graham’s ideas.

THE INTELLIGENT INVESTOR

AUTHOR: BENJAMIN GRAHAM

PUBLISHED: 1949

Buffett learned the art of investing from a number of books by Benjamin Graham, but first and most importantly, he came across The Intelligent Investor. The book came out in 1949 and soon became a standard reference work on value investing—an approach Graham developed while teaching at Columbia Business School in the late 1920s.

At the heart of the book is the allegory of Mr. Market, an obliging fellow who turns up every day at the shareholder’s door, offering to buy or sell his shares at a different price. Often, the price quoted by Mr. Market seems plausible, but sometimes it is ridiculous. The investor is free to either agree with his quoted price and trade with him or ignore him completely. Mr. Market doesn’t mind being ignored, though, and will be back the following day to quote another price.

The point of this anecdote is that the investor should not regard the whims of Mr. Market as a determining factor in the value of the shares the investor owns. And Buffett freely credits Graham’s book as guiding his own business strategies: first, that smart investors should profit from market folly rather than participate in it, and second, to concentrate on the real-life performance of companies and dividends rather than be too concerned with Mr. Market’s behavior.

Graham’s allegory offers the figure of Mr. Market as someone who is irascible and moody. Indeed, the more manic-depressive he is, the greater the spread between price and value, and therefore the greater the investment opportunities he offers. In his book The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America (1997), Buffett reintroduces Mr. Market, emphasizing how valuable he finds the allegory for disciplined investing. Another debt to Graham that Buffett is quick to acknowledge is in the margin-of-safety principle. This practical piece of wisdom holds that one should not invest unless there is a good reason to believe that the price being paid is substantially lower than the value being delivered.

Since the work was published in 1949, Graham has revised it several times, the last time being in the early 1970s for the fourth revised edition, which features a preface and several appendices by Buffett himself. (Any editions produced since 1976 are necessarily without Graham’s input as he died that year.)

Buffett unambiguously credits the book as his big inspiration. In an interview, he said of it, “It not only changed my investment philosophy, it really changed my whole life . . . I’d have been a different person in a different place if I hadn’t seen that book,” adding, “It was Ben’s ideas that sent me down the right path.”

Soon after (with a segue to study economics at the New York Institute of Finance), Buffett set up several business investment companies, including one with Graham himself. He created Buffett Partnership Ltd. in 1956 (the key “partners” being a company that made maps for the fire insurance industry and another that made windmills), and this firm in turn became Berkshire Hathaway in 1970 after it absorbed a textile manufacturing firm and became a diversified holding company.

Ever since Buffett became the chairperson of Berkshire Hathaway, he has been noted for holding firmly to two principles. The first is pretty much one that anyone might hold to: he says his company only invests in firms that he believes have long-term value and prospects. But the second principle goes much wider and relates to the responsibilities of wealth. The flamboyant lifestyle and baubles of luxury are not for Warren Buffett. Even today, he still lives in a five-bedroom stucco house in Omaha that he bought in 1957 for $31,500. Not for him the gilded palaces or architectural extravagances of other members of the superrich club.

Instead, despite his immense wealth, he concentrates on ways to put his money to good use. This strategy means that Buffett has pledged to give away not a measly 10 percent, as per traditional religious injunctions, but 99 percent of his fortune to philanthropic causes! How do you give away vast sums of money, though, without wasting it? Buffett’s off-the-peg (“ready to wear”) solution is to do so primarily through the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Cynics might note that this is a very unusual charity in that it regularly returns a substantial profit!

Addressing Colombia University’s centennial celebrations (in 2015), Buffett put it like this: “Leaders who use their talents not only to do something for themselves, but for others. Leadership that is creating ideas, creating products, creating whatever it may be that will benefit millions of people.”

In his philanthropy, as in his investing, Buffett follows Graham’s overarching principle that true investing is based on an assessment of the relationship between price and value. Buffett says, “You can gain some insight into the differences between book value and intrinsic value by looking at one form of investment, a college education. Education’s cost is its ‘book value’ and what is clear is that book value is meaningless as an indicator of intrinsic value.”

This is a big idea with political and social ramifications. Buffett warns that strategies that do not employ this comparison of price and value do not amount to investing at all but rather to speculation. A key principle of Buffett’s called the circle of competence principle follows naturally from this and is the third leg of the Graham/Buffett school of intelligent investing. This commonsense rule advises investors to consider investments only in businesses that they are capable of understanding.

Commenting once on why his investment company had bought a large shareholding in the Washington Post newspaper company at a time when such things were being generally shunned by the market, he said, “Most security analysts, media brokers, and media executives would have estimated WPC’s intrinsic business value at $400 to $500 million just as we did. And its $100 million stock market valuation was published daily for all to see. Our advantage was our attitude, that we had learned from Ben Graham, that the key to successful investing was the purchase of shares in good businesses when market prices were at a large discount from underlying business values” (emphasis added).

Likewise, in the annual letter for his company’s investors written in 1987 (starting with a reference to his vice president, Charlie Munger), Buffett follows Graham’s lead, saying,

Whenever Charlie and I buy common stocks for Berkshire’s insurance companies (leaving aside arbitrage purchases, discussed) we approach the transaction as if we were buying into a private business. We look at the economic prospects of the business, the people in charge of running it, and the price we must pay. We do not have in mind any time or price for sale. Indeed, we are willing to hold a stock indefinitely so long as we expect the business to increase in intrinsic value at a satisfactory rate. When investing, we view ourselves as business analysts, not as market analysts, not as macroeconomic analysts, and not even as security analysts.

This, of course, is the cue for Mr. Market to come in.

Ben Graham, my friend and teacher, long ago described the mental attitude toward market fluctuations that I believe to be most conducive to investment success. He said that you should imagine market quotations as coming from a remarkably accommodating fellow named Mr. Market who is your partner in a private business. Without fail, Mr. Market appears daily and names a price at which he will either buy your interest or sell you his. Even though the business that the two of you own may have economic characteristics that are stable, Mr. Market’s quotations will be anything but. For, sad to say, the poor fellow has incurable emotional problems. At times he feels euphoric and can see only the favorable factors affecting the business. When in that mood, he names a very high buy-sell price because he fears that you will snap up his interest and rob him of imminent gains.

But sometimes Mr. Market gets depressed and can see nothing but trouble ahead for both the business and the world. Investors should seek to insulate themselves from “the super-contagious emotions that swirl about the marketplace,” and, Buffett says, remember Graham’s dictum that in the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run it is a weighing machine. Or we might paraphrase to say that in the short run it is guided by opinions, in the long run by facts.

Such was certainly the case with the global subprime crisis of 2008 that ripped through the United States like a whirlwind, forcing tens of thousands of homeowners and firms to the wall and leaving whole national economies worldwide in tatters. For Buffett, it illustrated what happens when people invest hopefully in things they don’t actually understand. “Charlie and I are of one mind in how we feel about derivatives and the trading activities that go with them: we view them as time bombs, both for the parties that deal in them and the economic system.”

The problem, Buffett says, is that essentially such instruments call for money to change hands at some future date, with the amount to be determined by one or more reference items, such as interest rates, stock prices, or currency values. However, events such as the subprime crisis of 2007–2009 showed that many CEOs (or former CEOs) at major financial institutions were “simply incapable” of managing huge, complex books of derivatives. “Include Charlie and me in this hapless group,” Buffett acknowledges ruefully, adding that it took five years and more than $400 million in losses to “close up shop” on the complex web of 23,218 derivatives contracts with 884 counterparties that they ended up with after purchasing General Re (General Reinsurance Corporation) in 1998.1

Buffett’s other tips for investors are to beware weak accounting, to distrust unintelligible footnotes as indicative of untrustworthy management, and finally to be suspicious of companies that trumpet earnings projections and growth expectations. Instead of such things, Buffett says what needs to be reported is plain vanilla data that helps financially literate readers answer straightforward questions about how a company is actually doing and what is likely to be its competition in the future.

Judging the future, Buffett quickly acknowledges, is itself a dangerous game and “an expensive distraction for many investors and businessmen.” During the darkest days of the subprime crisis, for example, in an op-ed for the New York Times, he wrote that if you imagined how the world must have looked to people in the 1960s, no one would have predicted or foresaw the enormity of the Vietnam War, wage and price controls, two oil shocks, the resignation of a president, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a one-day drop in the Dow of 508 points, or Treasury bill yields fluctuating between 2.8 and 17.4 percent. The point being, he added, that a completely different and equally unpredictable set of major shocks was sure to occur for us in the next thirty years. “We should neither try to predict these nor to profit from them. If we can identify businesses similar to those we have purchased in the past, external surprises will have little effect on our long-term results.”

It is because future gazing is so prone to error that Buffett and his company avoid making predictions and tell their managers to do the same. They think it is a bad managerial habit that too often results in faulty reports.

Buffett just gives a simple set of commands to his CEOs: run your business as if you are its sole owner, it is the only asset you hold, and you can’t sell or merge it for a hundred years. Short-term results matter, of course, but his investment company’s approach avoids any pressure to achieve them at the expense of strengthening long-term competitive advantages. Buffett warns against friendly salespeople promising that their special portfolios of high-yield high-risk bonds can produce greater returns than more humdrum portfolios of safer bonds offering lower returns. As part of his skepticism of elaborate and complex schemes, he even recommends—boringly—that investors simply invest their money in an index fund that doesn’t require them to select anything because it simply tracks mainstream stocks. In this way, the smart investor can simply ignore the excited gesticulations of Graham’s imaginary Mr. Market. Buffett’s tip to investors, following as ever Graham’s book, is that their goal should simply be to purchase at a rational price a small stake in an easily understandable business with good prospects not for the next day or week but for five, ten, or even twenty years on. Oh, and if you aren’t willing to own a stock for ten years, he says, don’t even think about owning it for ten minutes.

In fact, in his own quiet way, Buffett is a champion of the public or, let us say, the small shareholder, against the investing elite, CEOs, and bosses. Indeed, surveying the wreckage of the subprime disaster, he commented unambiguously, “It has not been shareholders who have botched the operations of some of our country’s largest financial institutions. Yet they have borne the burden. The CEOs and directors of the failed companies, however, have largely gone unscathed. It is the behavior of these CEOs and directors that needs to be changed: If their institutions and the country are harmed by their recklessness, they should pay a heavy price—one not reimbursable by the companies.”

It is for this reason that Buffett, unlike many CEOs who desire their company’s stock to trade at the highest possible prices in the market, prefers Berkshire stock to trade at or around its intrinsic value (calculated by considering underlying fundamentals)—neither materially higher nor lower.

If you wonder whether all this stuff about ignoring Mr. Market seems a bit too obvious to really be an inspirational insight, Buffett notes that he is really quite a radical departure from standard economic thinking, in which “efficient market theory” (often abbreviated to EMT) became highly fashionable indeed, “almost holy scripture,” in academic circles during the 1970s. Buffett explains, “Essentially, it said that analyzing stocks was useless because all public information about them was appropriately reflected in their prices. In other words, the market always knew everything. As a corollary, the professors who taught EMT said that someone throwing darts at the stock tables could select a stock portfolio having prospects just as good as one selected by the brightest, most hardworking security analyst.”

To which Buffett says plainly, “We disagree,” and warns again against the academics who like to define investment risk by employing vast databases and statistical skills. The bottom line is whether EMT (the idea that markets know best) or the Mr. Market model (the idea that they don’t) is right. As to that, Buffett’s reading of Graham’s little book insisting the latter seems to have been a very good investment. Here is Buffett summing up his investment company again: “Our net worth has increased from $48 million to $157 billion during the last four decades. No other corporation has come to building its financial strength in this unrelenting way. . . . That’s what allowed us to invest $15.6 billion in 25 days of panic following the Lehman bankruptcy in 2008.”

Another socially progressive aspect of Buffett is that he prefers productive investments to merely profitable ones. This is a core idea in Adam Smith’s pioneering work on early economic theory, Wealth of Nations, where Smith describes the flow of cash in the economy as a great wheel of circulation and warns that simply buying gold and putting it in the ground deprives the economy of its lifeblood. As Buffett says,

Today the world’s gold stock is about 170,000 metric tons. If all of this gold were melded together, it would form a cube of about 68 feet per side. (Picture it fitting comfortably within a baseball infield.) At $1,750 per ounce—gold’s price as I write this—its value would be $9.6 trillion. Let’s now create a pile B costing an equal amount. For that, we could buy all U.S. cropland (400 million acres with output of about $200 billion annually), plus 16 Exxon Mobils (the world’s most profitable company, one earning more than $40 billion annually). After these purchases, we would have about $1 trillion left over for walking-around money (no sense feeling strapped after this buying binge). Can you imagine an investor with $9.6 trillion selecting pile A over pile B? My own preference is investment in productive assets, whether businesses, farms, or real estate.

Buffett’s notion of what is “productive” is quite generous, as over the years he has invested in media companies like ABC and in The Coca-Cola Company, things that Adam Smith would have run a mile from. Nonetheless, the fizzy drink company has turned out to be one of his most lucrative investments—at least up to 1998, when it peaked at eighty-six dollars a share. But then, knowing when a good thing has had its day is always the investor’s challenge. Buffett discussed the difficulties of knowing when to sell in the company’s 2004 annual report: “That may seem easy to do when one looks through an always-clean, rear-view mirror. Unfortunately, however, it’s the windshield through which investors must peer, and that glass is invariably fogged.” Likewise, in June 2010, Buffett defended the credit-rating agencies for their role in the US financial crisis, claiming, “Very, very few people could appreciate the bubble. That’s the nature of bubbles—they’re mass delusions.”

During the subprime crisis of 2007–2009, Buffett ran into criticism because he called the downturn “poetic justice,” but he was also purposefully scolding himself. His own company suffered a 77 percent drop in earnings in the third quarter of 2008, and several of his later deals suffered large losses.

One time, during a presentation to Georgetown University students in Washington, DC, in late September 2013, Buffett compared the US Federal Reserve to a hedge fund and stated that the bank was generating between $80 and $90 billion a year in revenue for the US government. Buffett also advocated further on the issue of wealth equality in society: “We have learned to turn out lots of goods and services, but we haven’t learned as well how to have everybody share in the bounty. The obligation of a society as prosperous as ours is to figure out how nobody gets left too far behind.”

In December 2006, it was reported that Buffett did not carry a mobile phone, did not have a computer at his desk, and drove his own automobile, a Cadillac DTS. In 2013, he had an old Nokia flip phone and had sent one email in his entire life. In contrast to that, at the 2018 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting, he said he uses Google as his preferred search engine. However, Buffett is not entirely frugal. As well as that modest stucco house in Omaha bought in the 1950s, he also owns a $4 million house in Laguna Beach, California. Oh, and he spent nearly $6.7 million of Berkshire’s funds on a private jet wryly named The Indefensible.

Buffett has written several times that in a market economy, the rich earn outsized rewards for their talents. His own children will not inherit a significant proportion of his wealth. Instead, he says, “I want to give my kids just enough so that they would feel that they could do anything, but not so much that they would feel like doing nothing.”

Buffett has stated that he only paid 19 percent of his income for 2006 ($48.1 million) in total federal taxes (due to their source as dividends and capital gains), while his employees paid 33 percent of theirs, despite making much less money. “How can this be fair?” Buffett asked, regarding how little he pays in taxes compared to his employees. “There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.”

Buffett favors the inheritance tax, saying that repealing it would be like “choosing the 2020 Olympic team by picking the eldest sons of the goldmedal winners in the 2000 Olympics.” In 2007, he testified before the Senate and urged them to preserve the estate tax so as to avoid a plutocracy. A final ethical conviction of Buffett’s is that he insists that government should not be in the business of gambling, or legalizing casinos, activities he calls taxes on ignorance.

All of this paints a picture of an all-too-rare creature—someone who has managed to retain their principles even while becoming rich enough to be tempted to ignore them. This aspect of Buffett has caused some sniping from the sidelines. In an article called “The Church of Warren Buffett: Faith and Fundamentals in Omaha,” for example, published by the liberal-leaning Harper’s Magazine in 2010, Matthias Schwartz describes Buffett as a man who “sits alone in a room, on the fourteenth floor of a gray building.”

“The man is the richest in the world,” Schwartz continues, more poetically than precisely, “except for certain years when he is the second richest.” If he wanted to, he could hire ten thousand people to do nothing but paint his picture every day for the rest of his life, Schwartz recalls is the example Buffett once gave of how much his money could buy, if what he wanted was money to spend. Of course he doesn’t do this because, as Schwartz says, I think both unkindly and inaccurately, “the man would rather stay in his room and watch his heap of money grow.” Thus he visits the same restaurant and orders the same steak. He goes home to the same house. He plays bridge on the Internet. Every other week he rides the elevator down to the basement of the gray building, where, in a tiny barbershop, he receives the same haircut.

Yet all the time, Schwartz says, Buffett is “living proof” that you can get rich without employing dubious means or borrowed money. He closes his piece by saying that the Buffett method is simply to sit in a room and think, but here too I think he is seriously off base, not least because, as we’ve seen, Buffett’s method, as the man himself makes plain to anyone who will listen, is actually to sit in his room and read.

As an investment guru, Warren Buffett is a unique case. It’s not really necessary to compare him to anyone else except, perhaps, in the sense of being a great philanthropist—a category there are regrettably few competitors in anyway. But there is one other fabulously rich businessperson whose life story echoes Buffett’s and who certainly believed in putting his wealth to good use, and this is the oil magnate John D. Rockefeller. At his peak, at the start of the twentieth century, Rockefeller’s net worth was around 1.5 percent of the entire economic output of the United States! Call it around $300 billion today. In his lifetime, Rockefeller donated more than $500 million (hundreds of billions of dollars in today’s money) to various philanthropic causes. He funded scientific pioneering of vaccines for meningitis and yellow fever. He set up the schools of public health at Harvard and Johns Hopkins universities to lead the case for public sanitation and supported international efforts to tackle scourges like hookworm and malaria. And he vigorously made the case for providing nationwide public education, without distinction of sex, race, or creed.

With his money Rockefeller created two great research universities, helped the American South out of chronic poverty, educated legions of African Americans, and dramatically improved health around the globe. It is not surprising that his biographer Ron Chernow concluded that Rockefeller “must rank as the greatest philanthropist in American history.”

Doing good works is not exactly straightforward either. Initially Rockefeller, as he noted later in his 1909 memoirs, distributed money in a “haphazard fashion, giving here and there as appeals presented themselves.” But by the early 1880s he was receiving thousands of letters a month, and most were “requests of money for personal use, with no other title to consideration than that the writer would be gratified to have it.”

The need to put his charity on a more methodical, indeed a businesslike, footing became crucial. At this point, a book seems to have helped guide his thinking. Extracts from the Diary and Correspondence of the Late Amos Lawrence describes the life of a cotton baron who had made his fortune in New England in the early nineteenth century and devoted his later years to giving it all away again. Upon Lawrence’s death in 1852 in Boston, his fortune was estimated at $8 million, or about $250 million in today’s dollars.

If Warren Buffett consumes books at the rate of two a day, Rockefeller seems to have barely managed that many in a decade. There are pointers to his interest in only a handful of texts, including those by Artemus Ward, Mark Twain, and Ella Wheeler Wilcox—apart, that is, from the Bible, a book he even led close readings of in his church community. On the other hand, the few books he read seem to have exerted all the stronger an influence, and none less crucial than William Lawrence’s summary of his millionaire father’s life.

One point the account makes, which surely spoke to Rockefeller as a loyal servant of the Baptist Church, was that Lawrence considered the Christian banner to cover many denominations and directed his charities to build up institutions under the influence of a wide range of sects “differing from that under which he himself was classed.”

The end result was that Lawrence was “renowned in his generation for a munificence more than princely.” He was “one of those rare men in whom the desire to relieve distress assumes the form of a masterpassion”; his benevolence was as “unsectarian as his general habits,” and “he stood ready to assist a beneficent design in every party, but would be the creature of none.” Lawrence gave not only largely but also wisely. The detailed accounts he kept of his work were not for ostentation, far less “the gratification of vanity,” but to make the most “of every pound he gave. With him, his givings were made a matter of business, as Cowper says, in an elegy he wrote upon him: ‘Thou hadst an industry in doing good, Restless as his who toils and sweats for food.’”

Books, themselves largely but not exclusively religious texts, were a key part of Lawrence’s charitable giving, both to colleges and individuals, and his son notes warmly that old and young, rich and poor shared equally in his distributions, and he rarely allowed an occasion to pass unimproved “when he thought an influence could be exerted by the gift of an appropriate volume.”

In his biography of Rockefeller, John Thomas Flynn says that the youthful Rockefeller was fascinated in particular by the book’s description of how Lawrence would instruct his secretary to bring him several hundred dollars in crisp one-, five-, and ten-dollar bills, adding that although he was not well enough to go out, he expected to have “some visits from my friends.” As to this, Flynn says that the “sober-faced boy [Rockefeller] thought ‘how nice that was’ and how, when he was rich, he would like to be able to give out nice, crisp bills.” Flynn says that although neither as a boy nor a man an avid reader, Rockefeller remembered this book and often spoke of it. Lawrence’s edited diary recounts how he converted several rooms in his house to coordinate the charitable giving process and how he first of all identified libraries and academic institutions, a children’s hospital in Boston, and the completion of the Bunker Hill Monument (where Lawrence’s father had fought during the Revolutionary War) as priorities. He also gave to many good causes on a smaller scale and took delight in giving people books from a bundle he kept in his carriage as he drove!

EXTRACTS FROM THE DIARY AND CORRESPONDENCE OF THE LATE AMOS LAWRENCE; WITH A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF SOME INCIDENTS OF HIS LIFE

EDITOR: WILLIAM R. LAWRENCE

PUBLISHED: 1856

Three strategies from this book seem to have influenced Rockefeller’s own decision to devote much of his energy not to the task of making money but to giving it away effectively and ethically. The book starts by describing these: the first is that it is not enough for a rich man to leave money to good causes in his will; it is necessary that it be given away in his lifetime. “By his course,” the book says reverentially, “Mr. Lawrence put his money to its true work long before it could have done anything on the principle of accumulation; and to a work, too, to which it never could have been put in any other way. He made it sure, also, that that work should be done; and had the pleasure of seeing its results, and of knowing that through it he became the object of gratitude and affection. So doing, he showed that he stood completely above that tendency to accumulate which seems to form the chief end of most successful business men; and which, unless strongly counteracted, narrows itself into avarice, as old age comes on, almost with the certainty of a natural law.”

The second strategy that made his charitable giving remarkable was “the personal attention and sympathy” with which he directed it.

“He had in his house a room where he kept stores of useful articles for distribution. He made up the bundle; he directed the package. No detail was overlooked. He remembered the children, and designated for each the toy, the book, the elegant gift. He thought of every want, and was ingenious and happy in devising appropriate gifts. In this attention to the minutest token of regard, while, at the same time, he could give away thousands like a prince.”

The importance of this expenditure of his own time lay in the fact that “man does not live by bread alone, but by sympathy and the play of reciprocal affection, and is often more touched by the kindness than by the relief.” Only this care and consideration for others creates the right relationship between the rich and the poor. If, Lawrence says, it is “a great and a good thing for a rich man to set the stream of charity in motion, to employ an agent, to send a check, to found an asylum, to endow a professorship, to open a fountain that shall flow for ages,” it is not the same thing as showing this kind of humanity and personal consideration. And so, his son writes, by Amos Lawrence, “both were done.”

The third very important thing Rockefeller clearly absorbed was that Lawrence’s daily actions were “guided by the most exalted sense of right and wrong; and in his strict sense of justice.” In this way, he demonstrated “the possibility of success, while practicing the highest standard of moral obligation.”

This, then, was the model for John D. Rockefeller when he retired from Standard Oil in 1897. He determined to step up his philanthropy with targeted assistance for his favorite educational, religious, and scientific causes. In 1913, the man who was now the United States’ first billionaire endowed the Rockefeller Foundation, which had the ambitious goal “to promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world.” The foundation contributed to achievements such as development of a yellow fever vaccine and the successful eradication of hookworm disease in the United States.

Despite this, Rockefeller is today often viewed with suspicion, not to say disapproval, as a proponent of social Darwinism who held the belief that the “growth of large business is merely a survival of the fittest.” Business books skip over his philanthropism and study only his careful strategies of anticipating market needs and developing timely new products. Here, like Buffett, he took a down-to-earth approach with one of his sayings being the schoolteacherly advice, “The secret to success is to do the common things uncommonly well.” However, in work matters, Rockefeller seems to have been a particularly ruthless operator.

John D. Rockefeller still ranks as one of the richest men in modern times and one of the great figures of Wall Street. Remarkably, he started life with almost no advantages. His father, William Avery Rockefeller, had to travel the country selling goods while his mother stayed home with the children. At least Rockefeller received a proper, indeed unusually good, education for his time and found work straight after leaving school as a commission house clerk at age sixteen. Within a few years, he left this to form a business partnership with oil driller Maurice Clark. The partnership would later become Rockefeller, Andrews & Flagler, a company focused on new products made in oil refineries rather than discoveries made by drilling.

The thing that distinguished Rockefeller from his competitors was his understanding of risk—something central to Warren Buffett’s success as well. Rockefeller realized that companies looking for oil had the potential for huge profits if they hit a deposit but that they steadily lost money when they didn’t. So Rockefeller focused on the certainty of income from the oil refining business instead. The profits were smaller but more reliable.

Disliking the way oil by-products were discarded during the refining process, Rockefeller invested heavily in research to find ways both to make the refining process more efficient and to find uses for the byproducts—as lubricants, grease, and later as Vaseline, paint, and many other useful products.

By 1890, Rockefeller’s company, Standard Oil of Ohio, was well ahead of the industry and enjoying a high profit margin. And Rockefeller used these profits to buy out competitors. When a competitor did not want to be bought out, Rockefeller used ruthless means of persuasion, including buying up essential materials, such as oil barrels or replacement parts, and causing shortages that crippled smaller companies; orchestrating price wars; and monopolizing essential transport by using his close relationship with the railroad companies.

Many competitors were forced to accept any offer Rockefeller made rather than try to fight against the tide of Standard Oil.

So where did Rockefeller catch the philanthropy bug? References to his idealistic, spiritual side seem to be secondhand and largely unreliable. For example, it is often claimed that under the influence of his mother, a devout Christian, Rockefeller had always tithed one tenth of his income to the local Baptist Church. However, a ledger of his gifts published by himself in 1897 tells an entirely different story.2

In the first year of his earnings, it notes his charitable contributions at a penny in the Sunday School plate every Sunday, far less than 10 percent of his fifty dollars annual income. The next year (1856), again according to his ledger, Rockefeller received a raise in his salary and earned $300. Following this, he made a raise in the Sunday School plate: he gave a dime a week instead of a penny.

Rockefeller spoke about his first few years’ earnings at the Young Men’s Bible Study Class at Fifth Avenue Baptist Church in 1897. Not once in his message to those young men did he say that he ever tithed his money to the church, nor did he tell the young men that they could be tithing their money to the church.

Here again, there is a popular myth that seeks to explain it. This starts by saying that the businessman met Swami Vivekananda, a charismatic spiritual leader and visionary from India, when he delivered a keynote address to the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago in 1893.

Vivekananda is said to have enhanced Rockefeller’s perception of philanthropy and inspired him to view himself as a channel for sharing his wealth with the world. The guru’s message was that each soul is potentially divine and that the goal of life is to manifest this divinity within by controlling nature, external and internal. This can be achieved through work, worship, mental discipline, or philosophy—that is, by one, or more, or all of these—and in this way enable the soul to become free again. This is the whole of religion. Doctrines, dogmas, rituals, books, temples, and forms are but secondary details.

Vivekananda is even supposed to have admonished Rockefeller for expecting to be consulted about the selection of a new president for Denison University, a college to which he had given many donations. One muchrepeated account, purporting to be of Rockefeller’s first meeting with the Indian mystic, as “told by Madame Emma Calvé to Madame Drinette Verdier,” describes how one day, Rockefeller was “pushed by impulse” to meet the “Hindu monk” who was visiting one of his friends. The account continues,

The butler ushered him into the living room, and, not waiting to be announced, Rockefeller entered into Swamiji’s adjoining study and was much surprised, I presume, to see Swamiji behind his writing table not even lifting his eyes to see who had entered. After a while, as with Calvé, Swamiji told Rockefeller much of his past that was not known to any but himself, and made him understand that the money he had already accumulated was not his, that he was only a channel and that his duty was to do good to the world—that God had given him all his wealth in order that he might have an opportunity to help and do good to people.

Madame Calvé goes on to say that Rockefeller was annoyed that anyone dared to talk to him that way and to tell him what to do. He left the room in irritation, not even saying good-bye! But about a week after, again without being announced, he marched into Swamiji’s study and, finding him there exactly the same as before, threw on his desk a copy of plans to donate an enormous sum of money toward the financing of a public institution.

“Well, there you are,” he said. “You must be satisfied now, and you can thank me for it.”

But it seems Swamiji didn’t even lift his eyes, did not move. Instead, taking the paper, he quietly read it, saying, “It is for you to thank me.” That was all.

A put-down to a man with a monstrous ego? Was this the real reason why, some twenty or so years later, America’s first billionaire endowed the Rockefeller Foundation, with the ambitious goal “to promote the well-being of mankind throughout the world”?

Madame Emma Calvé’s catchy tale appeals to our innate suspicion of other people’s natures. However, the original source seems to have been an article published by one M. L. Burke in a magazine called New Discoveries—along with the caveat that it was, ahem, not authenticated. Naturally, the caveat has been long forgotten, while the story itself has been repeated so many times that it has become part of standard Vivekananda history.

In this, a central part of the Indian guru’s greatness is that he was the one who persuaded Rockefeller to become a philanthropist. However, like much else said about Rockefeller, it is definitely not true. Curiously, it is not so much Rockefeller’s biographers but members of the Vedanta Society of Kansas City, with a particular interest in the study of Vivekananda, who have attempted to reclaim Rockefeller’s reputation and put the facts straight.

First of all, Rockefeller was already documented as a great philanthropist well before 1894. (For example, one of Rockefeller’s donations to the University of Chicago is detailed in the December 28, 1892, Chicago Daily Tribune.) Second, the assumption that Vivekananda gave Rockefeller the idea that “God had given him all his wealth in order that he might have an opportunity to help and do good to people” is incorrect—Rockefeller had long had that conviction. Third, the claimed incident could not have taken place in Chicago in 1894 as Rockefeller’s first visit to the university there would only be in July 1896 on the occasion of the dedication of the Haskell Oriental Museum. A trivial slip in the date for a meeting that did take place? But when Rockefeller really was in Chicago, Vivekananda was far away in Europe. Finally, there are the “psychological” aspects: Madame Calvé’s story offers a conceited and short-tempered Rockefeller, and even Vivekananda himself was not exactly polite. Neither portrayal seems accurate.

So how to explain the appearance of such a story? It turns out that Madame Calvé, the original source, was a theatrical diva in the negative sense of a star always seeking more limelight. It’s a fine piece of fiction, but as we have seen, the checkable details do not match the historical record, and it probably was never intended to become part of such.

Instead, the real moral impetus for Rockefeller’s philanthropic behavior seems to be more straightforward. The book that inspired Rockefeller to donate in today’s money hundreds of billions of dollars to good causes seems to have been . . . the Bible. Never underestimate that book. And as we have seen, the practical text that seems to have helped him to settle on the form his philanthropy should take was Amos Lawrence’s Extracts from the Diary and Correspondence of the Late Amos Lawrence.

Rockefeller is a rare figure in history, not only because of his wealth but also due to his lasting influence on the world in both the oil sector and philanthropy. He is sometimes presented as the antithesis to Henry Ford, who essentially did to the auto industry what Rockefeller did for oil, yet in their lifetimes Ford was applauded while Rockefeller was frowned upon and treated as controversial.

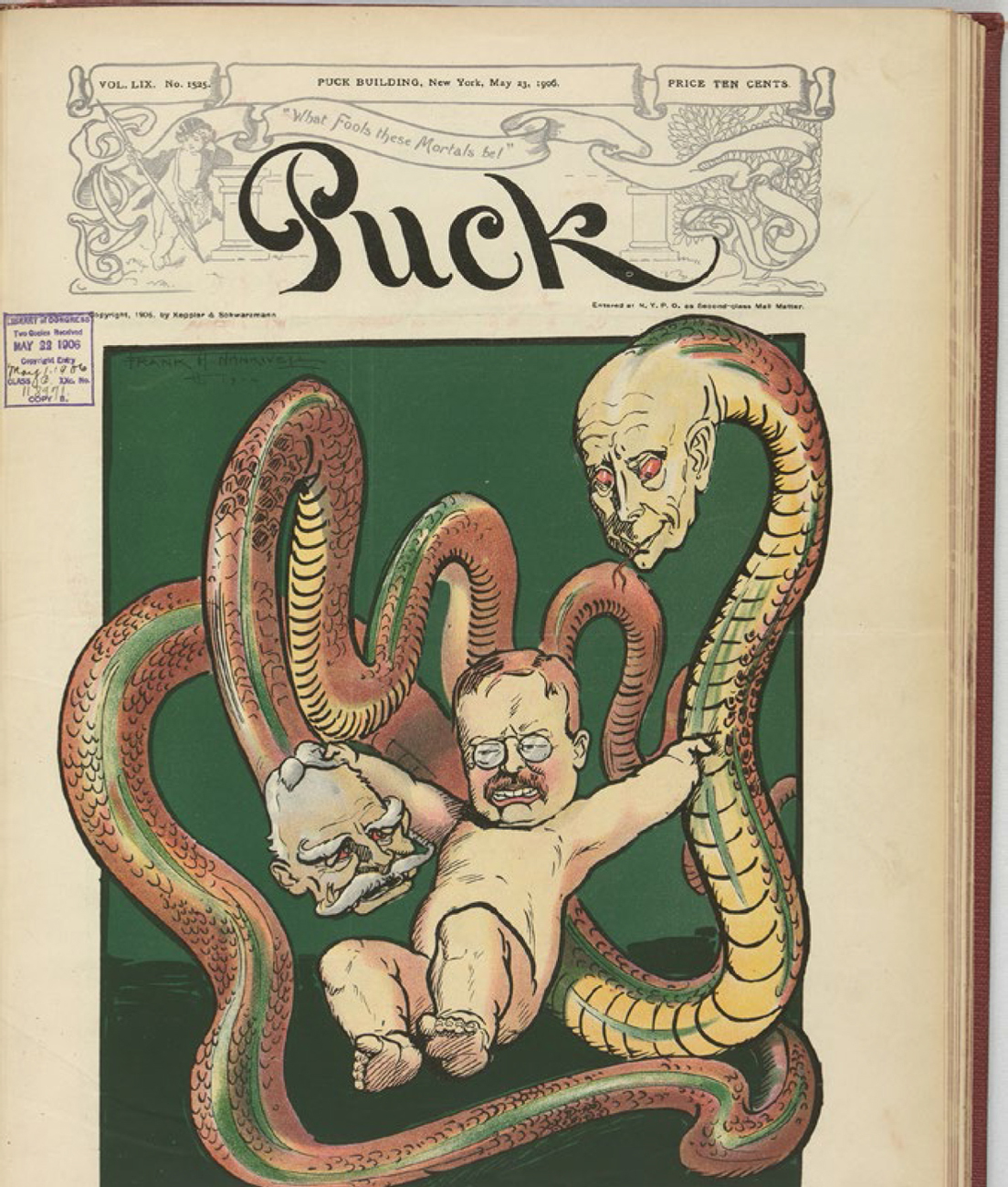

The power of the written word? Despite, by all accounts, being highly scrupulous and despite redefining the limits of philanthropy, Rockefeller has always attracted a hostile press. This cartoon, published in Puck magazine in 1906, depicts him as a dangerous snake, threatening US president Theodore Roosevelt (who the magazine supported). Five years later, Rockefeller’s company, Standard Oil, would be forcibly broken up after the Supreme Court ruled it was an illegal monopoly. (Frank A. Nankivell, Prints and Photographs Online Catalog, Library of Congress, n.d. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011645893/.)

Despite being so tough-minded in business matters, Rockefeller did not stint with his philanthropic efforts. He threw himself behind business and charity with the same vigor. Moreover, his path of building a fortune and then giving it away has become a template for wealthy individuals such as Bill Gates and his eponymous foundation.

Through Rockefeller’s own foundation, more wealth has been dispersed than Rockefeller personally earned during his lifetime. He inspired others like him to give even more. Some people might fault him for how he built his fortune, but his business practices and his philanthropy have ultimately benefited millions of people.

Many of us start life idealistic, with dreams of being a doctor saving lives, entering politics to win change directed at helping others, or maybe saving the environment as a green activist. Few of us actually end up following those dreams, but what Rockefeller illustrates very powerfully is that there are an infinite number of ways to do good in the world, and sometimes the most effective route is not the most direct one. And he obtained that inspiration from William Lawrence’s book about his father.

Notes

1. In financial dealings, every transaction must have a “counterparty” in order for the transaction to go through. Specifically, every buyer of an asset must be paired up with a seller who is willing to sell and vice versa.

2. The ledger is preserved by Colombia University Libraries Preservation Division and can be viewed online at https://archive.org/stream/mrrockefellersle00rock/mrrockefellersle00rock_djvu.txt.