Chapter 6

LOOK FOR THE “BIG EASY” (SKILL 5)

Our days are full of choices. Decisions – what, where, or when to eat, among others – face us every day. What to wear, where to go, what purchase is next, what color to paint the room, what flower to plant are just some of our many choices that seem simple to make. Some choices are more complex: What school should my child attend, should I take a job in another state, how do I invest for the best return, should I run for political office? All of these are questions we could encounter.

Individual choices are up to each of us. We decide what is best for ourselves. We may ask for input, but we in the end the choice is ours. But especially when we are part of a group and must make a choice, we look for ways that will be are fair to all involved and will meet the goals that the group has set for itself.

In Chapter 5, you learned about combining assets into opportunities. Assets can be combined to create a limitless set of opportunities, for all practical purposes. This is good news, but we can't do everything at once. To develop and implement an effective strategy, we must move at least one of our ideas to action. The reason is simple: our resources are limited. Often teams can get stuck at this point by ruminating about choices and what should come first. The fifth skill an agile leader needs involves efficiently sorting through many options to identify one that has the best chance of success.

DECISION‐MAKING METHODOLOGIES

You've probably used many different methods to deal with this challenge; here's a rundown of some of the most common. The first is consensus, in which everyone agrees to support a particular decision. The assumption is that this is in the best interest of the whole. The selected option may not be the favorite of each person but is the one the group as a whole will support. A dictionary might define consensus (at its best) as a sense of unity around a belief or proposed action. Consensus can be hard to achieve; groups that insist on it for philosophical reasons may find themselves taking a very long time trying to reach it. A modification of the consensus method takes into account that you may have one vocal individual who insists on their choice, while everyone else has coalesced around a different choice. This alternative is calledconsensus minus one. Everyone must agree, except one person. If that one person cannot convince another, we move ahead. But if at least two people do not agree with the majority, the group cannot yet move forward. The assumption behind this method is that if two people oppose a choice, there's probably some good reason. More conversation needs to take place.

Alternatively, you could vote, and let the majority's choice carry the day. This has the advantage of being straightforward. However, if the vote is close, you run the risk of continually being dragged back into a discussion about whether the choice was really the right one. A variation of the majority vote method (particularly if you are choosing among a large number of options) is to give each person a number of votes; each person can allocate as many of their votes as they want to any particular choice. One common way to do this is “sticky dot” voting, in which you give each person a number of small colored adhesive dots to use to cast their votes on a large piece of paper listing the options, and they can divide their dots among choices as they'd like. The items with the most votes (dots) rise to the top for more discussion and then a decision.

Majority choice voting has a significant shortcoming: each person is (generally) using one criterion to make their choice. They're thinking to themselves things like:

- That one would be quick.

- This wouldn't cost very much; let's choose it.

- That idea would be the most popular with our customers.

This shortcoming hides two deeper problems: first, there's been no discussion about what the criterion is or should be. The second is that if the challenge is really an adaptive one, thinking about things in light of only one factor is probably too simplistic. Some groups recognize this problem, and set up a very elaborate rating system in which every idea is evaluated using several criteria. Then all the ratings are totaled, sometimes weighted so that one or more criteria count more than others, and a “winner” is announced. This seems scientific enough, but in our experience, it's more trouble than it's worth. It can take the rest of the meeting, or even longer, just to set up the rating system (there are exceptions: in our work with NASA's life scientists, a complex rating system was unavoidable. There were a number of different factors, such as crew time on the International Space Station, budget burn rates, and the extent of the existing scientific knowledge base that participants had to consider).

All of these approaches to decision‐making have merit in particular circumstances. In choosing one of these, you are ensuring that decisions are made in a fair and transparent way – that is, there are no “backroom deals.” When the group considers the process fair, trust grows. As it does, the group's performance will improve.

Think back on a time when your enthusiasm for a project lagged and you may discover that the root cause was a lack of trust in the fairness of the process. People may not initially support a chosen idea, but if the process is fair their support can be earned. This fairness rule in selecting between options is key to the speed and success of implementation. When working with a group of people, especially when they do not report to each other but want to accomplish a difficult task together, building an open and fair process takes time and careful consideration of each person's views. In the long run this preparation work assures enthusiasm and desire for success by the team members implementing the agreed‐upon task.

In hierarchical organizations where the decisions are made above and then implemented below, there is less personal commitment to execution. The “back room” made the decision so your ownership is low (and the level of office gossip may be high!). The worst situation occurs when a team takes pains to make a careful decision, and their recommendations are seemingly ignored. To truly collaborate, as we saw in Chapter 1, trust has to be high. It takes time to build trust, and it pays dividends to be very careful in the beginning. As trust levels grow, speed increases. So, here's the paradox: if you want your organization to be fast and agile, go slowly at first. This is even more important for complex challenges in which there is a high level of ambiguity. How you choose among options has a tremendous impact on that level of trust.

THE 2×2 MATRIX

We recommend an alternative way to make these kinds of decisions: the 2×2 matrix. The matrix preserves the fair and transparent advantage of the other methods discussed earlier. It also allows you to consider two criteria at the same time.

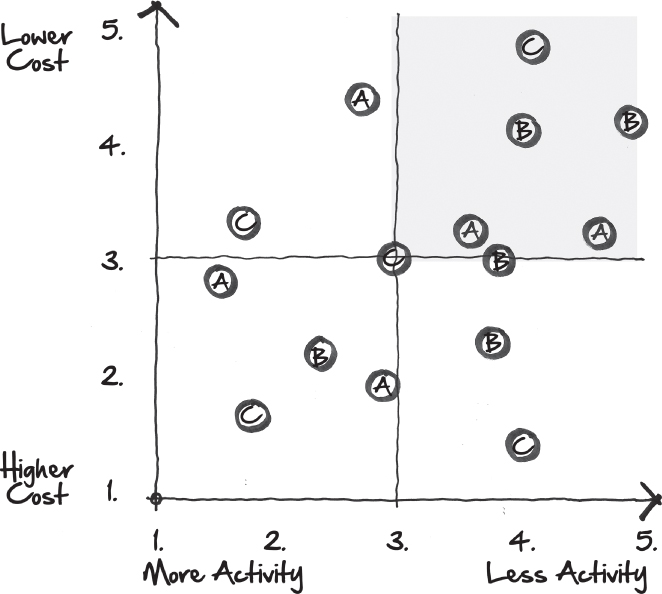

An example of a 2×2 matrix is shown in Figure 6.1. In this example, the decision to be made is where to locate a new school. The school board has identified three possible sites (A, B, and C). The criteria are the cost of construction (the sites are on different kinds of terrain) and the level of activity that would surround the new school (some are in neighborhoods, others are in more congested areas of the city; all things being equal, the board would like to site the school in a quieter area). Each of the five members of the school board makes their own evaluation of those factors and chooses a spot on the matrix for each location (so, there are 5 × 3 = 15 dots on the matrix). It wasn't obvious to the board what the right choice would be since there wasn't one site that was clearly both the quietest and the cheapest, but the matrix helps them visualize that there is, in fact, one choice that is probably optimal – Site B.

Figure 6.1 A 2×2 matrix.

2×2 modeling is used in countless disciplines, because while it seems simple, it helps draw out more sophisticated thinking from a group. Having to consider two criteria at the same time forces people to see “both/and” potential, rather than “either/or.” You naturally ask, “what if,” to generate alternative views. It is a flexible and potent tool.

Using the Matrix

To use this tool, there is a very important decision to make: Which two criteria should be considered?

You could use any two criteria you decide are best‐suited to your challenge, but we suggest two in particular: impact and ease of implementation (that's why we call it the Big Easy). You are looking for the opportunity that has the largest impact and is the easiest to implement. This sometimes seems counterintuitive to people. But stay with us.

Why these two criteria? Our experience is that selecting a first opportunity is critical to building the bonds of trust needed to move to the larger projects that will be needed for addressing complex challenges. You want people to be excited about what they are doing, and early success will keep them engaged for the long haul, drawing others in so that bigger opportunities are more achievable. As people build success by translating ideas into action, they are also building trust. As they are building trust, they are building the capacity to do more and more complex work together. Focusing on the Big Easy provides the right balance of a place to start.

The “Big” in the Big Easy inspires people and engages them emotionally. The “Easy” means that there are practical steps that can be taken now to move toward this opportunity. Taken together, these two dimensions ensure that the group has avoided two common risks: (1) selecting an idea that is very difficult to do and becoming discouraged, or (2) selecting something that is easy but inconsequential that no one will really care about.

If a team is working together for the first time, the chosen opportunity may indeed seem small and mundane. For example, we worked with a citywide group of citizens and leaders that was concerned that their community was on the decline. A major concern was a deteriorating downtown area – as in most cities, retail had moved out to the suburbs leaving an empty feel on Main Street. After a one‐day off‐site meeting about revitalizing the downtown, the team returned with a beautification project for planters in downtown. The reaction from those that had not been part of the session: “That's it?! All day to decide to build planters?” In reality, the planters were just the first step together, so the team could move to larger opportunities that involved deeper commitments. The group went on to revitalize their ailing downtown and found many ways to work together that would not have been possible before.

As this example shows, even though the Big Easy may seem quite small, resist the urge to go big. We've seen countless first projects like those planters – small efforts that attract attention that in turn attract more support. People generally want to join successful efforts, and that brings a wider range of skills and resources to the project. The network for the opportunity expands and larger, more complex work can be accomplished. People who once thought nothing could happen to improve a neighborhood, downtown, business, or organization notice the trend and want to lend their support to the project.

To understand why this happens, think back to our description of different kinds of people in Chapter 1. If you're just starting out, you probably have mostly pioneers around the table. The pragmatists are, for the most part, hanging back to see whether this effort will have staying power and if they can trust the group to treat them and their time well. If you pick an opportunity that is too ambitious and lose steam, you'll never get the pragmatists to join you. Demonstrate success, however, even with a small undertaking and they will be much more likely to throw their lot in with the group.

In some instances, a team's members may already know each other well. However, poor habits may have deflated the team. Perhaps they keep meeting with no decisions and no progress. Perhaps everyone has their own project in mind. Or, worse still, cynicism has eroded the will to do anything at all. The 2×2 matrix can help teams break through old habits and show their opportunities in a new light. It can rejuvenate a team around the potential for change and inspire others to join.

DEALING WITH DOUBTS AND DOUBTERS

This way of choosing a direction may seem quite unscientific. In fact, it depends on the powerful idea of group intuition. When there is a complicated choice to be made, one individual may or may not know exactly how much impact an idea will have, or how easy it will be to pull it off. However, if a group of reasonably well‐informed people all make individual judgments about the two dimensions of impact and ease, the combined weight of all of those judgments will lead the group in the right direction. In our experience, by using a 2×2 matrix to surface a shared strategic intuition, teams gain insights faster, learn faster, and act faster.

The odds are that the opportunity chosen really is your Big Easy. But what if you encounter doubters? Structuring your next steps in the same way that software developers do – taking baby steps to “try out” the Big Easy – is one way to respond to that worry. If the first steps toward your Big Easy opportunity prove that it was a dud, the group can easily go back and focus on another opportunity. This “tryout period” is an important advantage of agile strategy over traditional strategic planning. When months and thousands of dollars have been spent developing a strategic plan, it's very difficult to admit that some of the assumptions were wrong. With agile strategy, a limited amount of time will be “wasted” should the team be heading down what turns out to be a wrong path. Even if the group chooses the wrong opportunity to start, they will likely learn a lot from failure. If they quickly assess what's wrong and move on to another opportunity, chances are they have also strengthened habits of shared learning and candid communication. Facing hard facts together also builds trust. In this way, agile strategy enables you to manage risk in a way that traditional strategic planning never can.

Another common hesitation about using the Big Easy method is that it might appear to be premature to make any decision at all. That is, some members of the group may feel they need more information. But there is a real risk of delaying a decision on which opportunity to pursue. The group can become fixated on infinite fine tuning, ranking and reranking. Looking for more data can simply delay moving ideas into action. Because we are confronting complex, adaptive challenges, we must accept four realities. First, delay – too much talk without action – erodes trust. If getting more information is simply an excuse for not doing anything, the trust in your group will begin to evaporate. Second, it is impossible to have enough information to analyze a complex challenge completely before we begin. Third, we will only really learn about this complex challenge when we begin to do something together. We need to experiment and test our ideas. Fourth, you can be continuously both “generating” and “consuming” data by asking questions as you move forward. As you explore for answers, you will look for more data to guide you. We recommend you choose an opportunity that motivates the group to immediate action.

Sometimes it's tempting to combine opportunities to limit the scope of the choice – it feels safer than picking just one. However, we don't recommend this maneuver – the idea can get muddied and it's hard to tell if it is really a Big Easy. If the people making judgments are reasonably insightful, you can be confident that whatever you choose is probably very good.

Finally, you may find that what you chose as the Big Easy does not fit a progression that is in your (or someone else's) head for how the overall opportunity should come together. A debate may ensue about sequencing various ideas: What should come first? If the assets are in place to launch the Big Easy we recommend you move forward and not worry about the order. Given enthusiasm and desire for success, the team will find that once the first opportunity is accomplished, they can then move to the next opportunity and the order will address itself. Opportunities will connect over time, and the speed of your work will increase as your team grows. You'll also get better at spotting the next opportunity to take on.

PUTTING THE SKILL TO WORK: THE AGILE LEADER AS PRIORITIZER

Using the 2×2 matrix as a way to choose among different options is as simple as drawing a four‐square grid on a piece of paper (if you're working in a group, draw a large matrix on a flip chart). Put one criterion along the bottom, and another along one side. Label the ends of each of these axes – one end is high, another low. Each person votes by indicating where on the matrix they think each idea falls (an easy way to do this is to use sticky dots; assign each idea a different color or put numbers on them). The opportunity that has the most votes in the quadrant that represents high ratings for both criteria is the “winner.”

There are many ways that you can begin using the 2×2 matrix to help you to make choices. An interesting way to explore the idea is to practice finding the Big Easy in your own life. Make a list of projects at your house that you've been wanting to accomplish and evaluate them on the scale of impact and ease, or price and ease, or price and impact.

When you practice the Big Easy, you will find your skills for making choices improving. Agile leaders use these skills to help guide choices about which opportunities make the most sense, even when the environment is a complex one.