Chapter 12

TEN SKILLS. GOT IT. NOW WHAT?

In the past ten chapters, we introduced you to ten different skills. You can use any of these skills with the groups, teams, and organizations you're a part of and that are facing complex challenges. They take practice to master, but you will immediately see productivity gains. Fewer wasted hours in meetings. Less confusion over direction. More excitement and engagement in the work that you do.

Each of these skills stands on its own. Give some forethought, for example, to the strategic conversations you need to have. Take some time to make sure these conversations take place in both a safe place and safe space. This alone can be transformational; we've seen how that first skill, applied and reinforced, begins to change a tide of bad conversational habits. When people feel safe, they are more open to revealing and sharing their assets.

The second skill holds equal potential. Over and over, we've heard from groups that just talking about what the questionshould be – not even trying to answer it yet – has completely changed the conversations they are having. They've gone from having to beg people to attend meetings to having to train more leaders, because so many people want to be part of a group that is daring to dream a new dream.

Here's another example. If you're faced with several opportunities but have only enough time or money resources to do one, pull out the Big Easy matrix. You'll find that the two dimensions of this matrix help you find a good balance point between impact and ease of implementation. In 1772, Benjamin Franklin, writing to his friend, the eminent British scientist Joseph Priestly, explained how he made difficult decisions between two choices. He divided a piece of paper by drawing a line down the middle. On one side he listed “pro” reasons. On the other side he listed “con” reasons. He also attached weights to different reasons. He then compared his pro list to his con list to reach a decision. You can think of the Big Easy as a continuation of this tradition: using commonsense tools to make complex decisions. The Big Easy is a simple way to make your strategic intuition explicit and visible, either individually or in a group.

At this point we want to pause for a moment. As we near the end of this book, we might owe you a bit of an apology. We say “might” because whether an apology is needed depends on the expectations you had when you picked up this book. We thought long and hard about the title and the perspective from which we wrote the book. We eventually settled on the perspective of “leadership.” But we do not mean leadership in the traditional sense of the inspired individual sitting on top of the organization.

If you picked up this book thinking you would get insight on ten skills you can master to be the agile leader for your company, team, committee, or organization, then we do apologize. Why? Because you won't be able to completely master all ten. There will likely be one or two for which you are already very well‐suited; these are in your DNA or you've mastered them through years of experience. Several of the others you'll probably be able to develop to some level of expertise. At least a few, however, will probably always feel like writing with your nondominant hand – legible, but not effortless. Among the five of us who wrote this book, we each have different strengths: for example, Janyce is a master at developing appreciative questions. Ed's great at drawing undiscovered assets out of people.

If the title of the book were “Ten Skills for the Agile Leader,” we really would owe you an apology and maybe even your money back. Fortunately, we didn't use that phrasing. Instead, we promised ten skills for agile leadership and the leadership we have in mind rests with the collective, not the individual. Our focus is not on the individual leader but, rather, on leadership as a shared characteristic of a group or a team. Elsewhere in the book, we've used the phrase “distributed leadership” or “shared leadership.”

Shared leadership is defined as leadership that is carried out by the team as a whole rather than solely by a single designated individual. As we pointed out in Chapter 9, there is a growing body of research that points to shared leadership in teams and organizations as being positively associated with team effectiveness and productivity; and, that the relationship between shared leadership and effectiveness is even stronger when the team's work is highly complex. For some of us, that is a counterintuitive notion, because complexity can feel like chaos and in the midst of chaos we feel better when someone stands up and shouts, “I'm in charge.”

To better understand why shared leadership is effective in accomplishing complex work we go to the work of psychologist W. Ross Ashby. He wrote extensively about something called the Law of Requisite Variety. It is an idea so closely associated with him that it is sometimes referred to as “Ashby's Law.” Ashby pointed out that a complex environment is one that has a lot of variety, or a lot of variables. That's what makes it complex. Ashby said that any attempt to deal that complexity must have an equal, or requisite, amount of variety. Ashby's law has been stated and validated as a law of cybernetics (the science of communications and control systems). But if we dig a little deeper, Ashby's insight opens the door to an interesting and important understanding of why diversity matters when we work with complex systems and messy challenges. It's why shared leadership has become so important. Most of the time, a single leader will simply not have enough variety of experiences, skills, and expertise to manage their way through a complex situation.

In his book The Difference, Scott Page guides us further down this path of considering how our diverse qualities as individuals contribute to a group's functioning. By diversity, Page is not thinking about our identity – the external manifestations of diversity that we see in racial, ethnic, or gender differences. He refers instead to cognitive diversity, the different ways in which each of us sees the world. It's our internal differences, our cognitive skills, that matter. These other categories of diversity matter as well, but a group that looks diverse on the outside could still be thinking quite similarly on the inside.

Think about this point for a moment. With the complex challenges we face, we are dealing with large networks that we cannot see from a single viewpoint. Think of climate change, or a company trying to accelerate innovation, or gun violence in a poor neighborhood. While we can see certain manifestations of these challenges, we cannot see the underlying human systems that produce what we perceive. Our economy, our communities, our organizations: they all consist of shifting human networks embedded in other networks. Page is pointing out that we need a diverse set of cognitive skills, if we are to have any hope of understanding, designing, and guiding these networks.

It's one thing to accept that we need this kind of diversity, but quite another to figure out how to use the concept to make teams more effective. At the Purdue Agile Strategy Lab we are using a powerful team diagnostic tool developed by our partner Human Insight in The Netherlands. With this tool (called the AEM‐Cube®), we are learning how to assemble cognitively and strategically diverse teams. We are understanding why some people are really good at Skills 3, 4, and 5 and not so good at Skills 8, 9, and 10 (or vice versa). By engaging the full spectrum of our diversity, we can find the path toward more resilient, sustainable, and prosperous organizations and communities.

If you've paid attention to the stories we've told throughout this book, you'll notice that these were not primarily stories of individuals but of groups of people. In writing the book, we went back and visited with the people that were involved in each of those stories – even though one or more of us had been involved in the work at the time, we wanted to hear what had happened since as well as their reflections after some time had passed. When we asked them about their efforts, they didn't tell us stories of individual “champions” or stand‐out individuals; they told stories of shared leadership. Even when they're queried about their work and someone directly asks something like, “Who's the leader of this effort?” the answer usually includes several people, or even “We all are.”

Looking back, we have described ten skills that you can use to build and strengthen collaborative efforts. You can practice and share each of them:

- Building a safe space for deep and focused conversations.

- Using an appreciative question to frame your conversation.

- Identifying the assets at your disposal, including the hidden ones.

- Linking and leveraging your assets to create new opportunities.

- Identifying a big opportunity where you can generate momentum.

- Rewriting your opportunity as a strategic outcome with measurable characteristics.

- Defining a small starting project to start moving toward your outcome.

- Creating a short‐term action plan in which everyone takes a small step.

- Meeting every 30 days to review progress, adjust, and plan for the next 30 days.

- Nudging, connecting, and promoting to reinforce your new habits of collaboration.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER: STRATEGIC DOING

While each of the individual skills is a powerful tool, these skills also work together within an elegantly coherent framework. We have learned how to build complex collaborations following the simple ideas we have shared. To understand this point, think of a flock of geese or starlings. Their complex, unfolding formations emerge from each bird following a small set of simple rules. The same is true for human collaborations. Complex collaborations emerge when we follow a small set of simple rules. These rules – really, just the implementation of each of the skills –embed a lot of practices that academics have found valuable in a wide range of academic fields including psychology, strategic management, organizational development, cognitive science, behavioral economics, complexity economics, and cultural anthropology.

We've spent more than 25 years developing this coherent framework, and 10 or so learning how to teach it to others. We have tested it with space scientists at NASA and community leaders in Flint; faculty from many disciplines at more than sixty universities; engineers at a large defense contractor and small technology companies; executives and university administrators. We've worked with workforce, economic, and community development professionals; CEOs and management teams; educators and students; researchers and administrators; and government employees and elected officials.

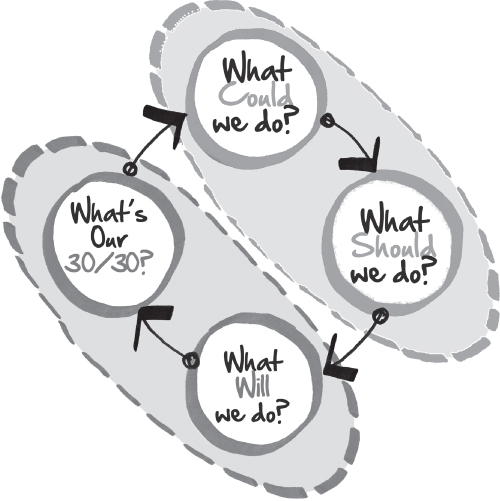

In most situations, we introduce this framework by presenting the challenge as of one of designing collaborative conversations. We tend to think that conversations “just happen,” but when we're facing complex challenges we can't leave it to chance – the conversation needs to be intentionally designed. Collaborative conversations start with what we call the Four Questions, shown in Figure 12.1:

Figure 12.1 The Four Questions of Strategic Doing.

- What could we do? What are all the possible opportunities before us – using only the assets that we already have – that might address our concerns?

- What should we do? We can't do everything; which, out of all the opportunities, should we pursue, and what would success look like?

- What will we do? Where will we start and what are the commitments we are making to each other to begin that project?

- What's our 30/30? When, exactly, are we going to get back together to share what we've done, so that we can learn from our experience, adjust if we need to, and plot out our next set of commitments?

You can probably see how each of the skills fits somewhere in this sequence. Skills 1 and 2 help you set the stage for productive, collaborative conversations. Skills 3 and 4 are the components of “What Could We Do?” – identifying new opportunities that draw on the assets we already have. Skills 5 and 6 make up “What Should We Do?” – picking the right opportunity and exploring it to make sure we are sharing what success looks like to all of us. Skills 7 and 8 become “What Will We Do?” – defining a small project we can do together in a short time frame to test out our idea. And “What's our 30/30?” draws on Skills 9 and 10, in which we make sure to come back together regularly and keep moving forward. As we do, we draw in new people and assets as we go.

As we work through these questions, we may come to a decision point for some reason: we finish our starting project. One of our ideas turns out to be impossible. Someone makes a pool of money available. What now? We start again with the first question, “What Could We Do?” It's a circle, after all.

We started this book by telling you that the set of skills in this book make up Strategic Doing. This is true, but it's when we use the skills in this particular way, asking the Four Questions in an iterative fashion, that Strategic Doing can be the most transformative. It's fundamentally different from traditional strategic planning, which is often a long, drawn‐out process for making investment decisions. Yet, we learned long ago that the more rigid and complex protocols of traditional strategic planning do not work well in a world increasingly driven by networks. We still face these difficult decisions about where to invest our limited time and resources, but we need to make the decisions in a very different fashion.

When we decided that we needed an entirely new discipline of strategy, we had to start with a simple question: What do we mean by strategy? We decided to impose a rigorous definition. As we described in the first chapter, an effective strategy answers two questions: Where we are going? and How we will get there? If we can answer these two questions, we have an effective strategy. Using this rigorous definition, we can quickly see why so many strategic planning efforts fail. They do not adequately answer these questions in a way that inspires engagement.

We designed the four questions of Strategic Doing to guide groups in filling that gap. The first two questions of Strategic Doing – What could we do? and What should we do? – give us the destination. They answer “Where are we going?” The second two questions of Strategic Doing – What will we do? And What's our 30/30?—provide us with a pathway, answering “How will we get there?” In traditional strategic planning, these questions are revisited at long intervals – at best, every year; more often, every 5 or 10 years. In contrast, in Strategic Doing we see that strategy emerges from a shared discipline of asking and answering these simple but not easy questions over and over. In this way, as we accumulate learning by doing, we refine our strategy. We build trust, and we design what's next. In the world of collaboration and networks, strategy becomes more like software development. Continuous iteration and improvement moves us forward to where we want to go.

Most of the case studies earlier in the book are of groups that used a comprehensive Strategic Doing approach – we've just focused in on one particular aspect of their story to illustrate the skill highlighted in that chapter. To explain more about how the approach works, let's turn our attention to some of the ways you can use Strategic Doing: as an individual, with a small group, or in a large initiative. We've also included a few more examples of our work which illustrate how a comprehensive Strategic Doing approach plays out.

USING STRATEGIC DOING AS AN INDIVIDUAL

The four questions of Strategic Doing provide you with a convenient template to design a collaborative conversation. One of our colleagues puts a map of the Strategic Doing cycle on the back of her office door. As she talks to colleagues on the phone, she refers to that list. “If we're not answering one of those questions,” she says, “then this isn't a strategic conversation. We are not working on our collaboration.” It helps her refocus her calls on doing meaningful work together rather than just having a “check‐in.”

Scott has another application, one that any parent of a teenager will appreciate. One day he asked his son an appreciative question: “What would it look like if your room was clean almost all of the time?” Caught off‐guard by the question, his son replied, “Well, you wouldn't tell me I couldn't go somewhere because my room wasn't clean.” (There's a measurable outcome!). Now Scott and his son can use that question to explore “What could we do?” It's not as if the room is suddenly always immaculate, but Strategic Doing has allowed him to have a different kind of conversation with his son, one that is hopefully much more productive.

Ed tells another story. Traveling to Stuttgart, Germany, Ed was exploring a collaboration with a German research institute, Fraunhofer IAO. He was able to arrange a two‐hour meeting with two of the principals in a research team on innovation. Ed was interested in exploring potential collaborations between Purdue and Fraunhofer IAO in innovation. He didn't tell them he was using Strategic Doing, but in his own mind, Ed was using the Four Questions to organize the conversation. During the meeting, he divided the time and made sure to get through all four questions. He moved the conversation along by asking these questions. On the airplane home, he drafted a strategic action plan that identified twelve potential opportunities, focused on two opportunities to start, and set forth both a starting project and an action plan. This strategic action plan has served as the foundation for a partnership that continues to strengthen each year.

Peter Drucker, the famed management scholar, said, “The important and difficult job is never to find the right answers, it is to find the right question.” Leadership in networks mostly involves guiding conversations by asking questions. Strategic Doing provides a powerful set of simple questions, so you can design and lead your own collaborative conversations.

USING STRATEGIC DOING IN A SMALL GROUP

If you're part of a task force, committee, or work team, you can use Strategic Doing to guide your work by using the skills sequentially. Think about a safe place, decide what the framing question is, and start your work together by talking about what assets you have. That's Skills 1–3. The rest follow in turn, with the caveat that Skill 10 is one that is ongoing, throughout the group's work.

A participant in one of our Strategic Doing workshops came to us afterward and asked, “Could I use this approach in my synagogue?” Indeed, several participants have used Strategic Doing with their churches and other faith communities. Facing a relatively large problem with relatively few resources is a common challenge for these groups. Designing conversations with Strategic Doing opens the door to more creative, horizontal thinking within the group.

Within the Purdue Agile Strategy Lab, Ed, Scott, and Liz use Strategic Doing to adjust the lab's strategy weekly. Instead of 30/30s we use 7/7s, because our environment is continuously shifting. We keep our central framing question in the back of our minds: “Imagine that the Purdue Agile Strategy Lab transformed the way strategy and collaboration are taught in universities across the globe. What would that look like?” We continuously look for the Big Easy opportunities that can help us answer that question. These opportunities are highly visible engagements that can serve as learning opportunities to everyone involved. We look for a local university partner, so we can replicate, scale, and sustain our work. When new opportunities pop up to fit our Big Easy criteria, we quickly make adjustments.

Here is a good example. Not long ago, we got a call from Yo‐Yo Ma's office. A world‐renowned cellist, Yo‐Yo is deeply interested in moving arts and cultural education to the center of conversations in our communities. Yo‐Yo had heard about our work in Strategic Doing, and he wanted to know if we could help design and guide a workshop for civic leaders in Youngstown, Ohio. The trick involved timing. Yo‐Yo's performance in Ohio was only a week out. Could we move that fast? We jumped at the opportunity. In our 7/7 meeting, we quickly made adjustments to enable us to seize the opportunity while keeping our other priorities on track.

Here's another example: we use Strategic Doing on Strategic Doing. The development of this new discipline is guided by a core team of about ten people, drawn from all over the United States. Each has been using the discipline for at least several years, and as a group we are committed to seeing it grow. Three times a year, we meet someplace for 1.5 days. During these work sessions, we organize our agenda using the four questions. One of us serves as a guide to keep us on track and aligned. Indeed, this book represents a Big Easy opportunity that emerged from one of our strategy sessions. For years, people have been pressing Ed to write a book on Strategic Doing, and for years he has deflected. The reason: until we had enough people who could teach people the ten skills of Strategic Doing and support them in using them, what was the point of writing a book? We now have a sufficiently large group of universities engaged with us to offer Strategic Doing training at least once a month somewhere in the world. Equally important, we have a large group of people with enough deep experience to both support the growth of Strategic Doing and to write a book.

USING STRATEGIC DOING WITH A LARGE INITIATIVE

In a larger context, Strategic Doing can be the new “operating system” for organizational or ecosystem transformation. It can (over time) help establish new, more productive patterns of thinking and behavior within an organization or community.

We gave you a window into a project Liz was part of in Chapter 8: an initiative to transform the undergraduate engineering experience at fifty universities. We focused on starting projects in that chapter, but the teams used Strategic Doing to manage their work more generally, starting with coming up with a framing question for their work.

As we discussed earlier, by the end of the three‐year timeframe, these 50 teams had launched more than 500 collaborative projects. Their projects included new courses and certificates, new university policies to give students more incentives to create new products, new “makerspaces,” even whole new university centers. In following up with the teams, Liz uncovered an even more important insight. The most productive teams consistently used (on average) eight of the ten skills of Strategic Doing. The least productive teams reported consistently using only two rules (again, on average). Although our research was not set up to examine causation (universities are complex places with many dynamics at work) we do see a strong correlation. We are continuing this line of research through our lab at Purdue. Our hypothesis is that following the Strategic Doing discipline makes teams and organizations more productive, and over time makes major transformations possible.

In another community, civic leaders in Rockford, Illinois, led by Rena Cotsones at Northern Illinois University (NIU), have used Strategic Doing to strengthen their aerospace companies. This critical sector of the Rockford economy is threatened by a looming shortage of engineering talent. In collaboration with industry partners and the local community college, NIU created a community‐based, industry‐integrated workforce development solution to address the demand for engineers. Rockford area students can now earn bachelor's degrees in mechanical engineering and applied manufacturing technology without traveling to NIU's main campus 40 miles away in DeKalb. Third and fourth year NIU courses are taught by NIU professors on the Rock Valley (Community) College (RVC) campus. Students have paid internships with area companies and are mentored by local NIU and RVC alumni.

In recognition of the importance of this initiative, local industry partners launched the “Engineering our Future” fundraising campaign and raised $6 million in nine months to support the program. The president of the lead donor company, Woodward, continues to host weekly Monday morning meetings with the higher education, industry, and community leadership team to ensure the successful operation and growth of the program. Using Strategic Doing, civic leaders in Rockford designed clear pathways from high school to community college to university to career. The initiative won a 2017 award of excellence by the University Economic Development Association.

Here's a final example. On the Space Coast in Florida in 2011, the future was clear – so clear, in fact, that it froze civic leaders. The space shuttle was shutting down, and the region's economy was facing a major transition. Lisa Rice, a workforce development professional, reached out to us with a simple question: “Can Strategic Doing help us?” For more than two years, civic leaders on the Space Coast had been trying to figure out a strategy for the dislocation that would take place when the space shuttle ceased operating. Despite multiple community meetings, they had not come up with any concrete actions. We did not have much time. Lisa's call came within a few months of the shutdown. We quickly organized an open forum. We organized tables around what we thought might be opportunities for the region.

When we opened the door, we saw a large group of people migrate toward one renewable energy table. The gathering got so large, we needed to break that conversation into two tables. Immediately, we saw there was an opportunity to explore how the Space Coast could develop its renewable energy assets. Within the space of a couple of hours, we were able to identify a Big Easy opportunity and define a project to move toward it. Out of that early work a new cluster of clean energy companies has formed on the Space Coast.

In making these large‐scale transformations, we have learned that it does not take a large army of people to start. Our best case for illustrating that point comes with the launch of the Charleston Digital Corridor. We mentioned Charleston when we introduced the brief history of Strategic Doing. Here's more of the backstory about how the Digital Corridor came to be. Ed found his way to Charleston when the Charleston Chamber of Commerce engaged him to develop a strategic action plan for the Chamber. During one of his early trips, Ernest Andrade, a city employee contacted Ed and asked for help. Ernest had an idea, but he was unsure of how to go about implementing it. He thought Charleston could become a dynamic hub for high‐growth digital businesses. In 2001, the idea seemed a bit far‐fetched. Charleston had no major research university, usually an anchor for such an ambitious idea.

During their first meeting, Ed asked Ernest about his assets. He did not have much: he had the enthusiastic support of the mayor (but no new budget), and he had his logo. That was it. He made clear that he did not have money to pay for a consultant. Ed and Ernest agreed to design and launch a strategy using a monthly breakfast meeting as a 30/30. Through these meetings, Ed taught Ernest how to think about building a cluster as a portfolio of collaborative initiatives: developing talent; building supports for entrepreneurs; developing quality, connected places to make Charleston “sticky” for start‐ups; and creating new narratives about the future of Charleston as a digital hub for high growth companies. Ed suggested a starting point, a Big Easy: create a monthly forum to model the behavior of collaboration that could power the Corridor forward. Ernest launched Fridays at the Corridor in 2001, and this regular meetup continues today as a central watering hole for Charleston's entrepreneurs. Today, the Charleston Digital Corridor is an internationally known ecosystem of high growth companies.

FINAL THOUGHTS

We want to finish back where we started: with the ideas in the Strategic Doing credo:

- We believe we have a responsibility to build a prosperous, sustainable future for ourselves and future generations.

- No individual, organization or place can build that future alone.

- Open, honest, focused, and caring collaboration among diverse participants is the path to accomplishing clear, valuable, shared outcomes.

- We believe in doing, not just talking – and in behavior in alignment with our beliefs.

The need for a new approach to the complex challenges in our world has never been greater. We face tremendous challenges in so many areas of our common life that describing them would fill another book and then some.

But what we also know, from our work in countless communities (only a few of which we've been able to tell you about in this book), is that while our political structures may seem permanently paralyzed, there are people in every community ready to roll up their sleeves, join arms with their co‐workers and neighbors and get to work. They're waiting only for new ideas about how to have conversations that will lead to real change. We believe the skills in this book are those new ideas, and we've written it because, as the credo says, we believe in doing, not just talking. We hope you will join us in this adventure.