CHAPTER TEN

Managing Employees, Programs, and Organizational Units

How can you ensure that managers and employees focus their attention on strategic goals and objectives and that top management's priorities are driven down through the management layers to the workforce at the operating level? To what extent can you use performance measures to help direct and control the work of people in the agency so as to channel their energy and efforts toward accomplishing important organizational goals? What tools or approaches can facilitate strategic management of programs with an eye toward performance? What kinds of performance management systems are used in public and nonprofit organizations, and what kinds of performance measures can support them?

Organizational performance and management constitutes a holistic approach that requires a degree of aggregation. In practice, though, organizations consist of various parts and components. These may be structural divisions, such as organizational departments or agencies, or programmatic divisions that require the cascading of measures. Cascading means translating the organization-wide measures to the program level, support units or departments, and then to teams or individuals. Cascading should result in alignment across all levels of the organization. The organization alignment should be clearly visible through linking strategic goals, performance measures, and initiatives. Scorecards, discussed in chapter 8 of this book, are used to improve accountability through objective and performance measure ownership, and desired employee behaviors are incentivized with recognition and rewards. Alignment of performance measurement among these various levels, as well as linkages among them throughout the measurement process, will strengthen organizational integration and support stronger overall performance.

The performance of the organization as a whole depends on the performance of each individual, each program, and each operational division. Disaggregating performance management to these levels can be challenging. This chapter examines the use of performance measurement in an organization's most important components: its human resources, programs, and the strategic management of organizational divisions.

Performance Management Systems

In order for an agency to function effectively, managers, employees, programs, and organizational units must direct their work toward meeting targets and accomplishing objectives that are consistent with higher-level goals and objectives, top management priorities, strategic initiatives, and the agency's mission. This can be accomplished by setting more specific goals and objectives, developing operational plans and providing the wherewithal, monitoring progress and evaluating results, and taking appropriate follow-up actions that are aligned with overall organizational goals. In chapter 1, we presented a performance management framework that includes strategic planning, budgeting, management (or implementation) and evaluation, all supported by performance measurement. All of the organization's endeavors should be guided by the strategic plan, or more specifically by the strategic goals and objectives identified in that plan.

The term performance management refers to large-scale processes for managing the work of people and organizational units so as to maximize their effectiveness and improve organizational performance. In chapter 1, we indicated that performance management refers to the strategic daily use of performance information by managers to correct problems before they manifest in performance deficiencies. The principal role of a performance management system is to collect performance data across the organization (including all programs and divisions), and analyze and report these data, thereby ensuring that they reach users with discretion to act at key decision junctures to maintain the organization's alignment with its strategic imperatives.

Various approaches are available to facilitate performance management within the organization, whether a public agency, a local government, or a nonprofit organization. We explore a few such systems in this chapter to provide the flavor of current practice and to highlight some of the challenges posed by implementing such systems. Systems of this nature are constantly evolving, so our review is a cross-sectional snapshot of the current state of practice.

In the way of organization-wide, systematic approaches, the most common examples are Management by Objectives types of systems, which are focused directly on individual managers and employees, as well as large-scale government-wide or department-wide programs such as CompStat in New York City and CitiStat-type programs such as in Baltimore and other midsized US cities. At the federal level, we find the Program Assessment Rating Tool used by Office of Management and Budget during the George W. Bush administration to offer one systematic approach to monitoring performance, comparing performance across units, and directing performance information into the decision process via budget proposals. (Since we discuss this program in chapter 1, we do not repeat it here.) Performance monitoring systems, which focus more generally on programs or organizations, are also considered to be performance management systems (Swiss, 1991), though they are the least sophisticated of the group.

In addition to these centralized and integrated systems, there are other approaches and tools available to managers that have influenced the quest for improved performance in policymaking, planning, and implementation. Two such tools introduced in this chapter are evidence-based practice and program evaluation.

We now turn our attention to a variety of systems that facilitate the integration of performance management with the day-to-day management of personnel, programs, and organizational units. The chapter begins by introducing and comparing Management by Objectives (MBO) and performance monitoring systems as approaches to encouraging a strategic performance orientation throughout the organization.

Management by Objectives

MBO systems have been used in the private sector for over fifty years as a way of clarifying expectations for individuals' work and evaluating their performance accordingly. Peter Drucker believed that the system was useful in the private sector but would lack success in the public sector. Others, such as Joseph Wholey, disagreed and extended the model's use to the public sector by incorporating information sharing with stakeholders (Aristigueta, 2002).

MBO was introduced in the federal government by the Nixon administration and has become widespread in state and local government over the past four decades (Poister and Streib, 1995). Generally it has been found to be effective in boosting employee productivity and channeling individual efforts toward the achievement of organizational goals because it is based on three essential elements of sound personnel management: goal setting, participative decision making, and objective feedback (Rodgers & Hunter, 1992). Although the term Management by Objectives has not been in vogue for quite some time, MBO-type systems are in fact prevalent in the public sector, usually under other names.

MBO systems are tied to personnel appraisal processes and thus usually operate on annual cycles, although in some cases they may operate on a six-month or quarterly basis. In theory, at least, the process has four steps:

- In negotiation with their supervisors, individual managers or employees set personal-level objectives in order to clarify shared expectations regarding their performance for the next year.

- Subordinates and their supervisors develop action plans to identify a workable approach to achieving each of these objectives. At the same time, supervisors commit the necessary resources to ensure that these plans can be implemented.

- Supervisors and subordinates monitor progress toward implementing plans and realizing objectives on an ongoing basis, and midcourse adjustments in strategy, resources, implementation procedures, or even the objectives themselves are made if necessary.

- At the end of the year, the supervisor conducts the individual's annual performance appraisal, based at least in part on the accomplishment of the specified objectives. Salary increases and other decisions follow from this, and individual development plans may also be devised, if necessary.

Thus, the MBO process is designed to clarify organizational expectations for individuals' performance, motivate them to work toward accomplishing appropriate objectives, and enable them to do so effectively. For an example, we can look at an action plan developed for a deputy manager in a medium-sized local jurisdiction aimed at increasing traffic safety on city streets. The plan is associated with the following MBO objective: “To reduce the number of vehicular accidents on city streets by a minimum of 15 percent below 2015 levels, at no increase in departmental operating budgets.” (Note that the objective is stated as a SMART objective, as discussed in chapter 4.) The following list, adapted from Morrisey (1976), outlines the action plan, which serves as a blueprint for undertaking a project aimed at achieving the stated objective:

Sample Action Plan

- Determine the locations of highest incidence, and select those with the highest potential for improvement.

- Set up an ad hoc committee (to include representatives of local citizens, traffic engineers, city planning staff, and police officers) to analyze and recommend alternative corrective actions, including education, increased surveillance, traffic control equipment, and possible rerouting of traffic.

- Establish an information-motivation plan for police officers.

- Inform the city council, city manager, other related departments, and the media about plans and progress.

- Test the proposed plan in selected locations.

- Implement the plan on a citywide basis.

- Establish a monitoring system.

- Evaluate initial results and modify implementation the plan accordingly after three months.

For this effort to be successful, it will be the responsibility of the city manager, the direct supervisor, to ensure the requisite resources in terms of cooperation from the participating departments.

Performance measures play a role at two stages in this MBO example. First, the action plan calls for establishing a monitoring system and using the data to evaluate initial results after three months. This monitoring system, which in all likelihood will draw on existing traffic enforcement reporting systems, will also be used after the close of the year to determine whether the expected 15 percent reduction in vehicular accidents has been accomplished. These data may be broken out by various types of accidents (e.g., single vehicle, multiple vehicle, vehicle-pedestrian) to gain a clearer understanding of the impact of this MBO initiative.

Alternatively, breaking the accident data out by contributing factors—such as mechanical failures, driver impairment, road conditions, or weather conditions—would probably be useful in targeting strategies as well as tracking results. In addition, depending on the kinds of interventions developed in this project, it may be helpful to track measures regarding patrol hours, traffic citations, seat belt checks, safety courses, traffic engineering projects, and so forth to provide further insight into the success or failure of this initiative. Thus, performance measurement plays an integral role in the MBO process.

There are several concerns with using a system like this to link individual performance to organizational goals. Let's consider a couple of the primary criticisms. First, employees will be reluctant to have their compensation tied to organizational or program performance when they perceive that such performance is beyond their control or influence. In the example, for example, driver actions and behavior is the direct cause of the accidents, and some traffic enforcement officers may have difficulty accepting responsibility for actions they do not directly control.

Some organizational goals may be subject to environmental factors beyond the control of any individual or the entire organization. For example, a major ice storm might strike with little warning, stranding motorists and leading to a considerable increase in accidents. To the extent weather patterns vary from year to year or quarter to quarter, the data may make it appear that performance was bad. In these cases, it will be necessary to construct a measurement system that controls for adverse events, perhaps by eliminating them from the performance score, or by indexing performance against that of neighboring cities to eliminate the performance reduction attributable to the adverse event. There are also low-incidence events that make MBO challenging. If we look to the field of public health, for example, one goal might be to prevent disease outbreaks. Such outbreaks are rare, and the likelihood that they would strike a given state or county in a given year are extremely low. Again, the agency takes responsibility for public health, but employees do not directly control the processes that lead to the outbreak, such as food contamination at its source in another state.

Bernard Marr (2009) indicates that implementing pay-for-performance systems in government, the public sector, and nonprofit organizations may be difficult or impossible. He also cautions that most systems that purport to reward individual-level performance actually measure completion of tasks without assessing the quality of that performance or whether it facilitated organizational performance. It may not be a good idea to base individual rewards on organizational performance for these reasons, but also because during years of fiscal cutback or restraint, there is little to no reward to allocate across employees.

Overall, MBO offers the potential to link organizational goals to individual evaluation. It is best to be able to identify individual-level performance objectives that logically map to the overall organization-level objectives. When that is done, individuals are able to take ownership of their actions as well as organizational performance. Care should be taken to develop systems that are fair, and it is essential that input from employees and managers forms the basis of a dialogue about what will be measured, how, and when, as well as how measures will translate into individual recognition, rewards, or penalties (when necessary).

Performance Monitoring Systems

At one level, performance monitoring is what this whole book is about: tracking key sets of performance measures over time to gauge progress and evaluate the results of public and nonprofit programs and activities. More specifically, performance monitoring systems constitute performance management systems designed to direct and control organizational entities, again by clarifying expectations and evaluating results based on agreed-on objective measures. Unlike MBO systems, performance monitoring systems do not focus so directly on the performance of individual managers and employees.

Although both MBO and performance monitoring systems seek to enhance performance through establishing clear goals and objective feedback, there are some key differences between these two approaches, as summarized in table 10.1 (adapted from Swiss, 1991).

Table 10.1 Key Characteristics of Pure MBO and Performance Monitoring Systems

| Dimension | MBO Systems | Performance Monitoring Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Principal Focus | Individual managers and employees | Programs or organizational units |

| Orientation | Usually projects | Ongoing programs or continuing operations |

| Goal Setting | Face-to-face negotiations | Often unilateral, based on past performance |

| Performance Measures | Outputs and immediate outcomes, along with quality and productivity | Outcomes emphasized, along with quality and customer service |

| Changes in Measures | Frequent changes as objectives change | Usually continuing measures with only rare changes |

| Data Collection and Monitoring | Done by individual managers; reviewed with supervisors | Done by staff and distributed in regular reports |

The most crucial difference between these systems is in their respective focus: whereas MBO systems focus attention directly on the performance of individual managers and employees, performance monitoring systems formally address the performance of programs or organizational units. Thus, MBO is a much more personalized process, bringing incentives to bear directly on individuals, whereas with performance monitoring processes, the incentives tend to be spread more diffusely over organizational entities. In terms of the overall management framework, MBO systems are usually rooted in personnel systems, whereas performance monitoring is usually carried out as part of strategic management, program management, or operations management. And these systems are often centralized in agencies such as the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) at the federal level, or state budget offices.

Based on the principle of participative goal setting, MBO objectives are usually negotiated in face-to-face meetings between pairs of supervisors and subordinates, often cascading from the executive level down to first-line supervisors, whereas higher-level management may set targets for performance monitoring systems unilaterally. In addition, whereas performance monitoring systems are usually oriented to ongoing programs, service delivery, or operations, MBO systems often focus on a changing mix of projects or specific one-time initiatives. Thus, MBO and performance monitoring represent two different approaches to performance management. It should be understood, however, that such pure versions of these systems are not always found in practice and that elements of these two approaches are often combined in hybrid systems.

Measures for Performance Management Systems

Measurement is a particularly interesting phenomenon with respect to the concept of performance management because the measures are intended to have an impact on behavior and results. Although researchers are usually interested in nonreactive measures, performance measures have a more overt purpose in monitoring systems. Performance measures are designed to track performance, and in performance management systems, they are used to provide feedback on performance in real time. For both MBO and performance monitoring systems, this feedback—usually in conjunction with targets or specific objectives—is designed to focus managers' and employees' efforts and to motivate them to work “harder and smarter” to accomplish organizational objectives. These systems are predicated on the idea that people's intentions, decisions, behavior, and performance will be influenced by the performance data and how they are used.

Both approaches are usually considered to be outcome oriented, but because MBO systems are so directly focused on the job performance of individuals, they often emphasize output measures as opposed to true effectiveness measures. Managers in public and nonprofit organizations often resist the idea of being held personally accountable for real outcomes because they have relatively little control over them. Thus, MBO systems often use output measures, and perhaps some immediate outcome measures, along with quality indicators and productivity measures over which managers typically have more control. Performance monitoring systems, in contrast, because they are less personalized, often emphasize real outcomes along with efficiency, productivity, and quality indicators and, especially, measures of customer satisfaction.

One basic difference between these two approaches to measurement is that because MBO systems are often project oriented, with a varying mix of initiatives in the pipeline at any one time, the measures used to evaluate a manager's performance tend to change frequently over time. In contrast, performance monitoring systems tend to focus on ongoing programs, service delivery systems, and operations, and therefore the measures used to track performance are fairly constant, allowing trend analysis over time. Finally, the measures used to assess individuals' performance in MBO systems are usually observed or collected by those individuals themselves and reported to their supervisors for the purpose of performance appraisal, whereas performance monitoring data are usually collected by other staff who are assigned to maintain the system and report out the data.

MBO Measures

The measures used to evaluate performance in MBO systems address different kinds of issues because those systems often specify a variety of objectives. During any given MBO cycle, an individual manager is likely to be working on a mix of objectives, some of which may well call for improving the performance of ongoing programs or operations, and in fact the appropriate measures for these kinds of objectives may well be supplied by ongoing performance monitoring systems. In addition, though, managers often specify objectives that focus on problem solving, troubleshooting particular issues, implementing new projects, undertaking special initiatives, or engaging in self-development activities intended to strengthen work-related knowledge and skills. For the most part, the measures defined to evaluate performance on these kinds of objectives will be substantively different from those tracking ongoing programs or activities, and they are likely to be shorter-term indicators that will be replaced by others in subsequent MBO cycles.

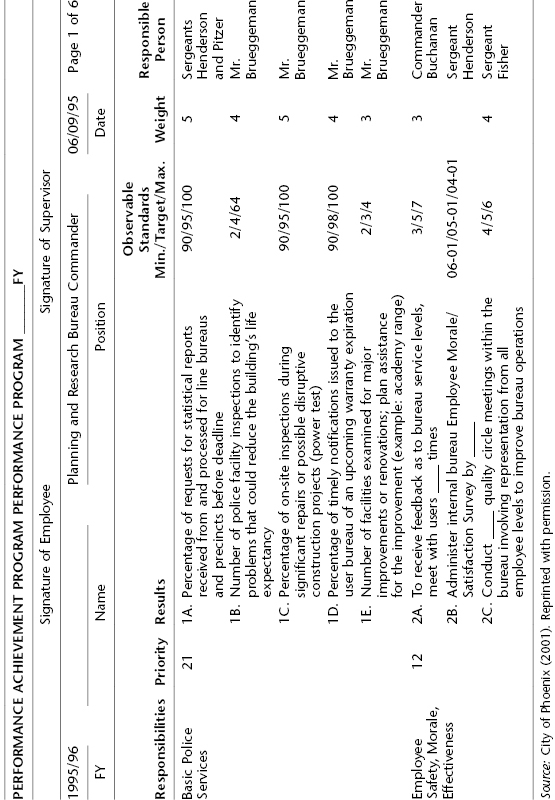

In some cases, MBO systems focus largely on ongoing responsibilities and employ continuous measures to track the performance of individual managers. For example, table 10.2 shows the first page of numerous specific objectives established for one fiscal year for the commander of the Planning and Research Bureau of the Phoenix, Arizona, police department. The objectives are clustered in different areas of responsibility and are weighted by their relative importance. This example is also notable for its specification of maximum attainment, target levels, and minimum acceptable levels of performance. With respect to the first objective, regarding the processing of certain statistical reports, for instance, the target level is to process 95 percent of these reports before the deadline, the minimum level is set at 90 percent, and the maximum is 100 percent.

Table 10.2 Performance Achievement Program: City of Phoenix

Most of the measures in this particular example are expressed as percentages or raw numbers. They are fairly typical performance indicators calibrated in scale variables that can be evaluated against target levels, and most of them can probably be tracked as going up or down over time because they concern ongoing responsibilities of this particular officer. However, one of these objectives, concerning the administration of an internal employee survey within the department, sets alternative dates as targets, and the indicator is operationalized as a discrete measure of whether a given target date is attained. It is also interesting to note that all the objectives in this example relate to outputs or quality indicators, not to outcomes or effectiveness measures.

Individual and Programmatic Performance Management

Performance measures are often essential to the effectiveness of performance management systems designed to direct and control the work of people in an organization and to focus their attention and efforts on higher-level goals and objectives. Governmental and nonprofit agencies use both MBO-type performance management systems and performance monitoring systems to do this. Monitoring systems are essentially measurement systems that focus on the performance of agencies, divisions, work units, or programs, whereas MBO-type systems focus on the performance of individual managers and, in some cases, individual employees. MBO systems often make use of data drawn from performance monitoring systems, but they may also use a number of other discrete one-time indicators of success that are not monitored on an ongoing basis.

Because MBO systems set up personal-level goals for individuals, managers and staff working in these systems often tend to resist including real outcome measures because the outcomes may be largely beyond their control. Because managers are generally considered to have more control over the quantity and quality of services produced, as well as over internal operating efficiency and productivity, MBO systems often emphasize measures of output, efficiency, quality, and productivity more than outcome measures. Because performance monitoring systems are less personalized, they are more likely to emphasize true effectiveness measures.

MBO systems and performance monitoring systems are both intended to have a direct impact on the performance of managers, employees, organizational divisions, and work units. However, for this to work in practice, the performance measures must be perceived as legitimate. This means that to some degree at least, managers and employees need to understand the measures, agree that they are appropriate, and have confidence in the reliability of the performance data that will be used to assess their performance. Thus, building ownership of the measures through participation in the process of designing them, or “selling” them in a convincing manner after the fact, is of critical importance. It is also essential that the integrity of the data be maintained so that participants in the process know that the results are fair.

Individual Targets and Actual Performance: Community Disaster Education Program

Some MBO-type performance management systems prorate targets over the course of a year and then track progress on a quarterly or monthly basis. For example, local chapters of the American Red Cross conduct community disaster education (CDE) programs through arrangements with public and private schools in their service areas, primarily using volunteer instructors. In one local chapter, which uses an MBO approach, the director of this program has a number of individual objectives she is expected to achieve during the fiscal year, including such items as the following:

- Launch professional development training for teachers in CDE.

- Institute Red Cross safe-schools training packages in schools.

- Initiate a new CDE training program, and recruit five volunteer instructors.

- Upgrade the CDE curriculum.

- Launch the Masters of Disaster curriculum kits.

- Train twenty-two thousand youth in CDE.

- Continue to develop and implement program outcome measures.

Most of these objectives are stated in general terms, and there is not a clear indication of precisely what will constitute success in accomplishing them. Only two of them have established target levels, but others could be reformulated as SMART (specific, measurable, ambitious, realistic, and time-bound) objectives. Performance on others will be determined based on periodic reviews of progress in activity intended to realize the objectives; in the director's annual performance evaluation, judgments will have to be made by her supervisor regarding whether she accomplished certain of these objectives. Thus, it is not surprising that one of the director's objectives is to “continue to develop and implement program outcome measures.”

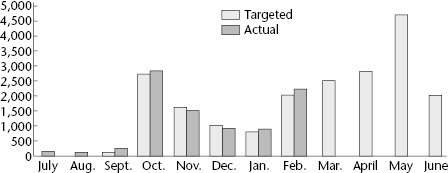

In contrast, the objective to train twenty-two thousand youth in CDE programs can be monitored directly. As shown in figure 10.1, the overall number of youth targeted to receive this training has been prorated over the course of the twelve-month fiscal year, based in part on seasonal patterns in this activity in prior years, as well as on the director's understanding of the feasibility of training particular numbers of youth in different months. Thus, this outcome measure can be tracked on a monthly basis and compared against the monthly targets in order to track her progress in reaching the target. Although the director has fallen slightly short of the targets in November and December, overall she is running slightly ahead of the targets over the first eight months of the fiscal year. However, the targets for March through June appear to be quite ambitious, so it remains to be seen whether the overall target of twenty-two thousand youth trained will be met by the end of the fiscal year.

Measures for Monitoring Systems

For the most part, performance monitoring systems track measures that pertain to ongoing programs, service delivery systems, and activities at regular intervals of time. Whereas MBO systems often include a mix of continuous measures along with discrete indicators of one-time efforts (e.g., the satisfactory completion of a particular project), performance monitoring systems focus exclusively on measures of recurring phenomena, such as the number of lane-miles of highway resurfaced per week or the percentage of clients placed in competitive employment each month. Whereas MBO-type performance management systems typically draw on information from performance measurement systems as well as a number of other sources, performance monitoring systems actually constitute measurement systems.

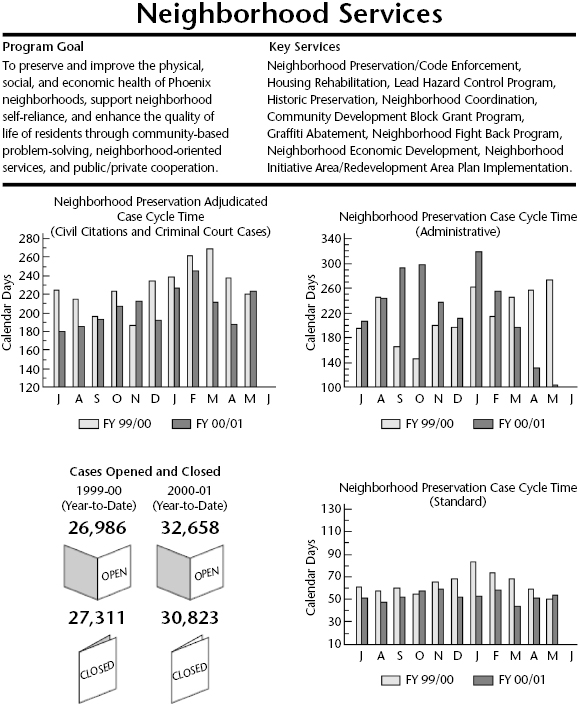

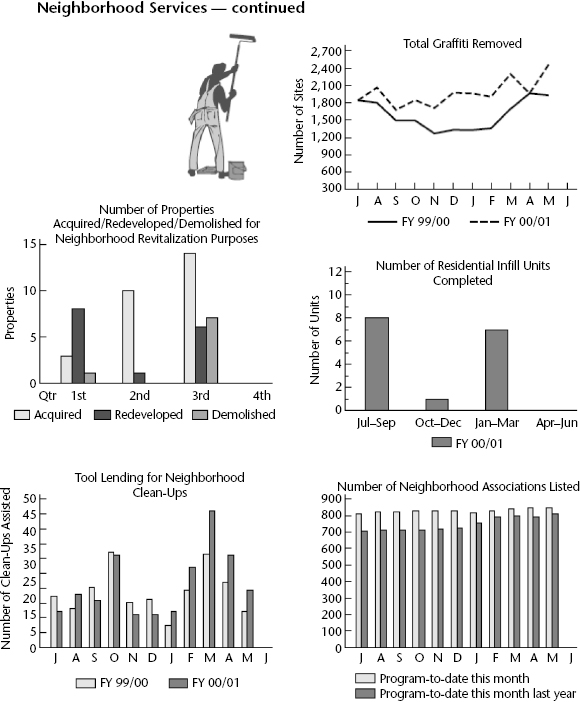

For example, cities like Phoenix use monitoring systems to track the performance of each operating department and major program: community and economic development, fire protection, housing, human services, parks and recreation, police, and public transit—on a variety of indicators on a monthly basis. Each month, the performance data are presented in the City Manager's Executive Report, which states the overall goal of each department, identifies the key services provided, and affords data on a variety of performance indicators, most often displayed graphically and emphasizing comparisons over time.

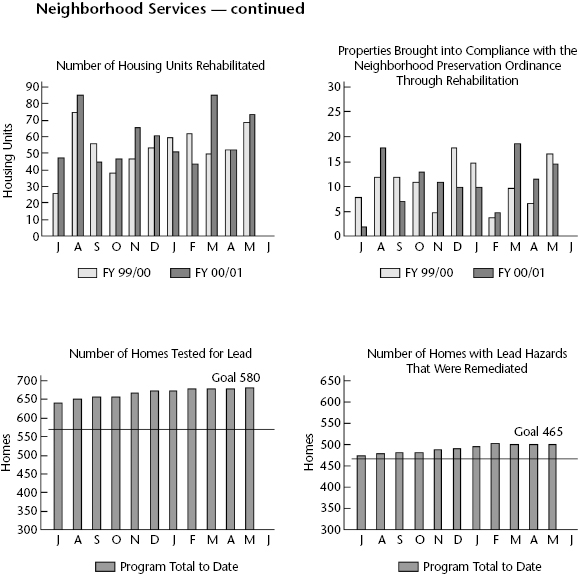

Figure 10.2 presents excerpts of the performance data for Phoenix's neighborhood services program, taken from a sample edition of the City Manager's Executive Report. All of these measures are presented on a rolling twelve-month basis (with May therefore the most recent month with data available); the report also shows data from the previous year to provide more of a baseline and to facilitate comparing the current month's performance against the same month in the prior year, which is particularly relevant for measures that exhibit significant seasonal variation, such as the number of neighborhood cleanup efforts assisted.

As we might expect, many of these indicators tracked on a monthly basis are output measures, such as the number of residential infill units completed or the number of properties acquired, redeveloped, or demolished for revitalization purposes. Others focus on service quality, such as the cycle time for adjudicating or administering neighborhood preservation cases in terms of average calendar days. A couple of outcome measures are also incorporated into this portion of the report. For instance, whereas the number of housing units rehabilitated is an output measure, the number of properties brought into compliance with the neighborhood preservation ordinance is an outcome indicator. Similarly, whereas the number of homes tested for lead is an output indicator, the number of homes with lead hazards that were remediated is a measure of outcome.

Performance Monitoring: The Compass

Many public agencies use performance monitoring systems as management tools. The Compass system of the New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department (NMSH&TD) constitutes a prototypical case in point. The Compass incorporates seventeen customer-focused results, and there is at least one performance measure for each result, with a total of eighty-three measures at present. Whenever possible, the measures have been chosen on the basis of available data in order to minimize the additional burden of data collection as well as to facilitate the analysis of trends back over time with archival data. However, as weaknesses in some of the indicators have become apparent, the measures have been revised to be more useful.

The seventeen results tracked by the Compass range from a stable contract letting schedule, adequate funding and prudent management of resources, and timely completion of projects, through smooth roads, access to divided highways, and safe transportation systems, to less traffic congestion and air pollution, increased transportation alternatives, and economic benefits to the state. Each result has an assigned “result driver,” a higher-level manager who is responsible for managing that function and improving performance in that area. Each individual performance measure also has a measurement driver, assisted in some cases by a measurement team, who is responsible for maintaining the integrity of the data.

The Compass was initiated in 1996, and for four years, it constituted the department's strategic agenda. NMSH&TD has since developed a formal strategic plan; the bureaus and other operating units develop supportive action plans, all tied to Compass results and measures. However, the top management team still considers the Compass the main driving force in the department. Thus, a group of one hundred or so departmental managers—the executive team, division directors, district engineers, and middle-management “trailblazers”—meet quarterly to review the Compass. They conduct a detailed analysis of all eighty-three performance measures to assess how well each area is performing, identify problems and emerging issues, and discuss how to improve performance in various areas. NMSH&TD officials credit their use of the performance measures monitored by the Compass with significant improvements in traffic safety and decreases in traffic congestion and deficient highways over the past five years.

Compstat, CitiStat, and Similar Performance Management Systems

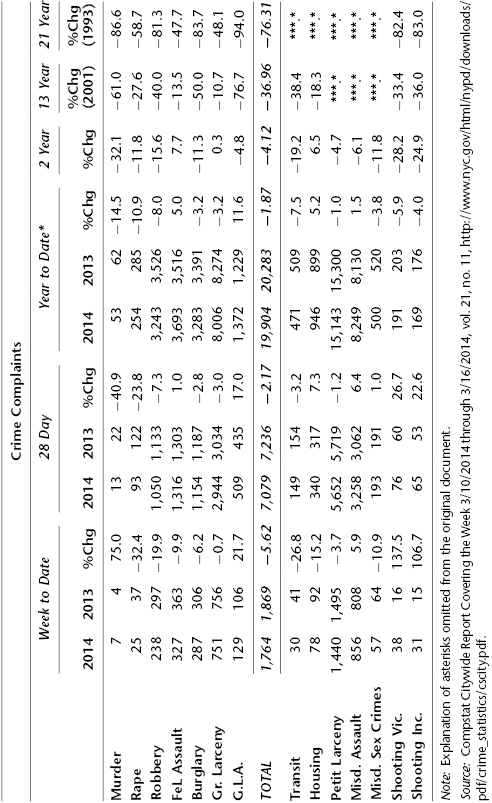

There has been a growing trend among local governments to pay closer attention to performance at the department, unit, or program level. New York City Police commissioner William J. Bratton adopted CompStat (Comparative Statistics) as a department-wide accountability system to monitor, map, and measure crime at the precinct level to identify particular problems; weekly meetings between police department executives and precinct commanders provide forums in which problems are discussed and strategies and approaches to problem solving are presented and adopted. Table 10.3 offers an excerpt from a weekly citywide CompStat report that reveals crimes by type and trends over time. Precinct-level reports offer similar comparisons.

Table 10.3 Excerpt from Weekly New York City CompStat Report, March 16, 2014

Variations of the CompStat system have been replicated by other New York City departments, as well as departments in other governmental units around the world. Importantly, these systems seek to integrate the broad strategy of an entire organization with the individual units that comprise it. They are effective because they orient management functions around strategic performance goals and focus management attention on spots where performance is falling behind in key performance measures. The system relies heavily on current and reliable performance data to shape daily decisions.

One particularly fascinating model that mirrors the CompStat approach is the City of Seoul, Korea, OASIS system (oasis.seoul.go.kr). OASIS was adopted by the Seoul Metropolitan Government during the administration of former Mayor Oh Se-hoon. OASIS combines e-government, citizen participation, analysis, and action through a multitiered approach intended to garner improved performance through citizen trust in government and increased satisfaction and quality of life. Although it is not formally a performance monitoring system, OASIS takes citizen ideas and suggestions that are clearly related to overall government performance. The system takes in ideas through a web-based portal—as mundane and simple as sidewalk cracks destroying high-heeled shoes—and vets them through online citizen votes and online discussion by bloggers. Ideas that make it through the voting stage and the blogging discussion are then forwarded to the government research think tank for evaluation, including cost-benefit analysis. Certainly performance information is collected and considered during this process to the extent it is available. The result is a recommendation to the mayor.

Recommendations are reviewed during monthly televised sessions where the mayor takes decisive action on the recommendation. Not all ideas are approved, and not all action is taken at the recommended level, but citizens feel that they have a role to play in government, that their voices matter, and the result is a feeling of increased satisfaction and trust.

Systems like this offer a glimpse of the future for performance monitoring systems. They conceptualize performance in a way that goes beyond tracking daily outputs and yearly outcomes to get to the heart of what citizens care about. This system does not replace traditional performance monitoring systems; they are up and running in city departments at a magnitude that would startle most municipal leaders in the United States. Transportation system performance is tracked in real time in a command-center type of environment. Call center performance is tracked on key performance indicators on an ongoing basis, right down to the individual level, and displayed on screens in the call center in real time. But OASIS tackles a dimension of performance that is often overlooked yet is at the very heart of democratic systems: aspects of government services that affect and frustrate citizens daily.

Taking lessons from other large-scale municipal performance management systems, CitiStat provides a citywide statistical performance monitoring framework. CitiStat, the original city “stat” program, was launched in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1999. The program was modeled after CompStat by initiating regular meetings with managers responsible not only for police services but for all municipal functions. While known commonly as CitiStat programs, these approaches are also referred to as “PerformanceStat” systems or approaches (Behn, 2008). The system was designed to foster accountability by requiring agencies to provide CitiStat analysts with performance data. Then, during regular meetings with the mayor's office, each agency is required to identify, acknowledge, and respond to performance at levels below expectation with targeted solutions. In large part, these programs work under the philosophy of the old adage that “the squeaky wheel gets the grease,” meaning that problem spots are warranted attention and smooth-functioning components are left alone so as not to disrupt strong performance.

Central to the success of CitiStat is the formation of a core group of performance-based management analysts charged with monitoring, and continually improving, the quality of services provided by the City of Baltimore. Their charge extends to evaluating policies and procedures used by city departments to deliver services. These analysts examine data and identify areas in need of improvement. Each city agency participates in a strictly structured presentation format; they must be prepared to answer any question that the mayor or a cabinet member raises. The nature of the CitiStat model is such that it emphasizes multiple dimensions of performance simultaneously; hierarchical control, or controllability (Koppell, 2005) is achieved through the regular meetings, and the substantive focus of those meetings on performance addresses the accountability dimension of responsiveness. A quick glance at Baltimore's success with CitiStat explains why the model has been adopted by cities all around the world (http://www.baltimorecity.gov/Government/AgenciesDepartments/CitiStat/LearnaboutCitiStat/Highlights.aspx):

Baltimore CitiStat Performance Results

- Year 1: CitiStat helps the City of Baltimore save $13.2 million, including $6 million in overtime pay.

- Year 3: Overtime is reduced by 40 percent; absenteeism is reduced by 50 percent in some agencies.

- Year 4: CitiStat saves the City of Baltimore over $100 million.

- Year 5: CitiStat receives the Harvard Innovation in Government Award.

- Year 7: CitiStat saves the City of Baltimore $350 million.

- 2014: The CitiStat approach has become institutionalized. The model covers broad multiagency goals such as keeping Baltimore clean. CitiStat has been incorporated into the budgeting process to hold recipients of city funds accountable for their performance. Control and accountability are ensured by employee knowledge that subpar performance levels will be addressed at CitiStat meetings.

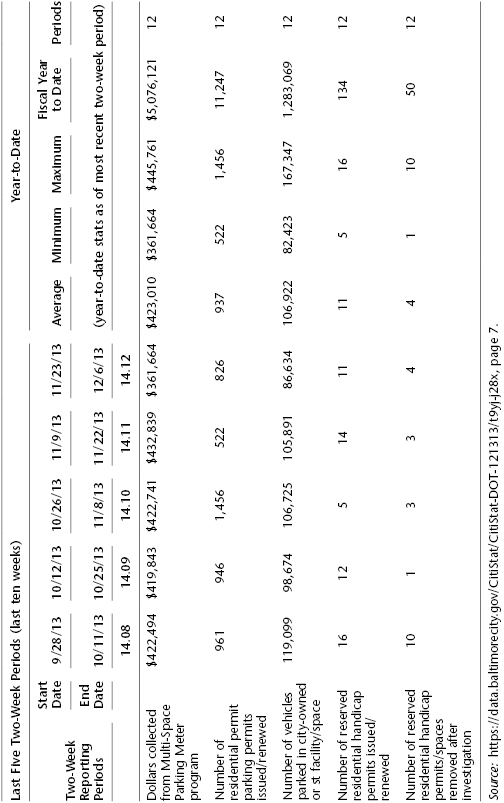

The city is open and transparent about department performance. Reports are made available to the public through an online portal. (Reports are available at https://data.baltimorecity.gov/browse?q=CitiStat&sortBy=relevance.) Table 10.4, from Baltimore's parking management program, offers a simple example of the format of CitiStat reports.

Table 10.4 Baltimore CitiStat Report: Parking Management Program

These programs offer examples of what the Center for American Progress refers to as governing by the numbers—a trend in public sector management that focuses management attention on performance in areas of strategic focus or concern (Esty & Rushing, 2007). Central to their success is monitoring of key indicators, analysis and breakout by units, and identification of problems, areas of poor performance, or trends out of sync with expectations. By highlighting problems, such systems are able to reorient management attention to correct deficiencies immediately to limit potential damage.

While a number of cities and large departments have adopted CitiStat-like programs that are similar in form and function, there are important qualitative differences at work in such systems, particularly with respect to management and leadership style. The Baltimore example is very confrontational—almost to the point of the mayor or mayor's executive leadership team taking the part of frustrated citizens demanding improvement. Other cities administer their programs in a more collegial and collaborative fashion, such as that of Providence, Rhode Island.

Like most other performance management systems or approaches, the key to success is to first determine the purpose for which the system is being adopted. The purpose frames the approach and shapes the selection of measures, the frequency of measurement and so on. Behn (2008, p. 202) provides a list of eight steps that leaders of the adopting agency or government need to follow:

- Specify the performance purpose they hope to achieve by using the strategy.

- Determine what performance data will be collected and analyzed.

- Build administrative capacity by allocating staff to be responsible for the analysis function.

- Assemble necessary infrastructure.

- Determine how they will conduct leadership meetings.

- Assemble the necessary operational capacity.

- Create an explicit mechanism to follow up on any problems that have been identified, solutions that have been proposed, and decisions made at those meetings.

- Carefully think through how to adapt features of other PerformanceStat systems to their own purpose and situation.

The importance of purpose should be clear. It shapes every decision about the structure and operation of the system. As with many other policy or program adoptions, replication is often the goal. Managers, mayors, and other leaders see an example like Baltimore and want to adopt the approach. Bardach (2004) tells us that there are three things that can be done with someone else's idea: adopt it (which is akin to replication), adapt it (meaning that key features are preserved but adaptations are made to better suit it to local context and purpose), or be inspired by it (which means that a completely new, and potentially better, approach might be inspired by these systems). Whatever the case, it is almost always easier to adopt but wiser to adapt. Similar issues are experienced in another tool that managers use to manage programs—evidence-based practice.

Evidence-Based Practice

The use of evidence-based practice as an approach to choosing programs, policies, and practices has become commonplace in governance as a way to preemptively ensure performance, and thus accountability. By picking programs that have already been shown to work in other implementing environments, managers limit the level of risk they incur from trying new or untested programs, ensuring greater returns on investment. In the way of program management, evidence-based practice offers managers a tool for selecting high-performing strategies before or during implementation. Following on the lessons of CitiStat, evidence-based practice might be employed when a performance problem is identified during regular monitoring. Managers could use the evidence-based practice approach to select a proposed solution to introduce during monthly management meetings with the mayor. Like most other tools, there are limitations and criticisms to evidence-based practice as well. Among them are the potential to stifle innovation, the homogenization of public services across places, and concerns resulting from disagreement about what constitutes evidence.

As a subset of the field of best practices (Hall & Jennings, 2008), evidence-based practice is subject to the flawed interpretation that it is a mechanism for identifying the best possible way to do something. That it is not. Rather, it examines the available evidence to recommend a strategy or approach—a mechanism, if you will—that brings about the greatest level of some specified outcome. The outcome of choice is subjective, not universally accepted, and remains within the purview of program administrators. One program might emphasize efficiency, for example, while another emphasizes effectiveness. Evidence-based practice could easily lead to different recommended approaches for each of these implementation settings.

Evidence-based practice can be used systematically at the highest levels. For example, in Oregon, the legislature passed a law requiring all agencies to expend their program budgets on evidence-based practices. It can also be used within divisions or programs (where resources are sufficient) as a method of coping with bounded rationality. Much like policy analysis, the use of evidence-based practice requires establishing a set of values and criteria, searching for a set of practices intended to address the stated problem, collecting evidence on the effectiveness of each practice relative to the selected criteria, and adopting the alternative that results in the highest expected outcome, allowing for sensitivity to weighting across the identified criteria. It is an approach for organizing information, and like all other rational approaches, it will be limited by time and resources to continue the search. Most managers will attenuate their search when little new information is emerging.

Jennings and Hall (2012) reveal considerable differences in the extent to which scientific information is weighed among possible sources of information across different areas of public policy practice. This, of course, results partly from a lack of evidence in some fields (such as economic development) that do not present themselves readily for experimental research and partly from differences in opinion about what types of information are important in making policy decisions. For example, in areas where the questions are mostly instrumental—about how to achieve an already agreed-on goal—evidence may be weighted very heavily. In areas where questions are mostly political—about what should be done—values and ideology may dominate the policy debate. Managers can draw on evidence-based practice at all levels of governance from the legislature, where it can be used to influence broad policy action, to programs and departmental divisions where it can influence the adoption of standard operating procedures or approaches to implementing street-level practices that most directly affect citizens on a daily basis.

Let's look more closely at Oregon's case. Senate bill 267, now ORS section 182.525, not only mandates the use of agency resources on evidence-based practices but calls for agency performance assessment in their fulfillment of this requirement and links that performance to subsequent appropriations. Agencies must spend at least 75 percent of state funds received for programs on evidence-based programs. Agencies then submit biennial reports that delineate programs, the percentage of state funds expended on evidence-based programs, the percentage of federal or other funds expended on evidence-based programs, and a description of agency efforts to meet the requirements. The law defines evidence-based programs as those that incorporate significant and relevant practices based on scientifically based research and that are cost effective. It defines scientifically based research as follows:

Scientifically based research means research that obtains reliable and valid knowledge by:

- Employing systematic, empirical methods that draw on observation or experiment

- Involving rigorous data analyses that are adequate to test the stated hypotheses and justify the general conclusions drawn

- Relying on measurements or observational methods that provide reliable and valid data across evaluators and observers, across multiple measurements and observations and across studies by the same or different investigators. (ORS sec. 182.515)

This strict law was implemented incrementally, allowing agencies time to cope with the unfunded mandate. But it does not discuss or offer any interpretation regarding differences in the quality or availability of evidence across fields of practice. Oregon offers an interesting example of a state preemptively institutionalizing high-performance programs.

Program Evaluation

Evidence-based practice is a tool most suited for selecting a practice when the desired end is known or selecting a particular management or implementation strategy within the bounds of bureaucratic discretion. Program evaluation is a management tool used at the conclusion of the performance management cycle to assess program effectiveness and causality. In other words, program evaluation seeks to determine the extent to which the observed effects on selected outcomes are attributable to the program itself. Although performance measurement may be a more cost-effective alternative to program evaluation, particularly for answering the question, “What happened?” it does not allow users to address the deeper question: “Why did these results occur?” Other differences have been documented as well.

Program evaluation has many similarities to performance measurement, but seven key differences have been identified (McDavid, Huse, & Hawthorn, 2013, p. 324):

- Program evaluations are episodic; performance measures are designed and implemented with the intention of providing ongoing monitoring.

- Program evaluations are related to issues posed by stakeholders' (broadly defined) interests in a program. Performance measurement systems are intended to be more general information gathering and dissemination mechanisms.

- Program evaluation requires at least partially customized measures and lines of evidence. Performance measures tend to rely heavily on data gathered through routinized processes.

- Program evaluations are intended to determine the causal attributes of the actual outcomes of a program. Whereas in performance measurement attribution is generally assumed.

- Program evaluation requires targeted resources. Performance measurement is usually part of a program or organizational infrastructure.

- Program managers are not usually included in evaluation. In performance measurement program managers are key players in developing and reporting of results.

- Program evaluation requires a statement of the intended purpose. Use of performance measurement will evolve over time to reflect needs and priorities.

Program evaluation has many similarities to performance measurement but also a number of key differences. In particular, program evaluation focuses on the causality between the program and outcomes of interest. To do this, it relies on evaluation methods and research designs to determine causation, which means greater cost and caution than one finds in routine performance measurement.

There are at least three advantages to integrating program evaluation with performance measurement in a performance management strategy:

- Program evaluation may be used to validate the measures and ensure overall data quality (Aristigueta, 1999).

- The data generated during performance measurement may be useful for the analysis conducted during program evaluation.

- Program evaluation is able to statistically validate the program theory expressed in the logic model.

These tools are widely used approaches to managing people, programs, and organizational units. Reflecting on the performance management model we presented in chapter 1, it should be clear that these approaches will be most effective when they are integrated carefully with the organization's strategic approach to performance management. Efforts to eliminate redundancy should be made, and the tools should be integrated into the overall management strategy rather than added as strictly symbolic layers of reform. This requires understanding the relevant role each tool can play. Whereas evidence-based practice is a tool most suited for selecting a practice when the desired end is known or selecting a particular management or implementation strategy within the bounds of bureaucratic discretion, program evaluation is a management tool that can assist in program performance management after a full implementation cycle by establishing or validating causal relationships. Program evaluation seeks to determine the extent to which the observed effects on selected outcomes are attributable to the program itself.

There are two advantages to integrating program evaluation with performance measurement in a performance management strategy. First, the data generated during performance measurement may be useful for the analysis conducted during program evaluation. Second, program evaluation is able to statistically validate the program theory expressed in the logic model. Understanding these relationships may lead to discoveries that require changing strategies or approaches in order to bring program implementation into conformity with the observed reality. Where program evaluation reveals that reality differs from the hypothetical relationships expressed in the program logic model, the model must be revised, which may alter the selection of performance measures and measurement strategy.

Understanding these relationships may lead to discoveries that require changing strategies or approaches in order to bring program implementation into conformity with the observed reality. Where program evaluation reveals that reality differs from the hypothetical relationships expressed in the program logic model, the model must be revised, which may in turn alter the selection of performance measures and measurement strategy.

References

- Aristigueta, M. (1999). Managing for results in states. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

- Aristigueta, P. (2002). Reinventing government: Managing for results. Public Administration Quarterly, 26, 147–173.

- Bardach, E. (2004). Presidential address—The extrapolation problem: How can we learn from the experience of others? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23, 205–220.

- Behn, R. D. (2008). Designing PerformanceStat: Or what are the key strategic choices that a jurisdiction or agency must make when adapting the CompStat/CitiStat class of performance strategies? Public Performance and Management Review, 32, 206–235.

- City of Phoenix. (2001). City manager's executive report: June 2001. Phoenix: Author.

- Esty, D. C., & Rushing, R. (2007). Governing by the numbers: The promise of data-driven policymaking in the information age. Center for American Progress. http://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/issues/2007/04/pdf/data_driven_policy_report.pdf

- Hall, J. L., & Jennings, E. T. (2008). Taking chances: Evaluating risk as a guide to better use of best practices. Public Administration Review, 68(4), 695–708.

- Jennings, E. T., & Hall, J. L. (2012). Evidence-based practice and the use of information in state agency decision making. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 22, 245–266.

- Koppell, J. G. (2005). Pathologies of accountability: ICANN and the challenge of “multiple accountabilities disorder.” Public Administration Review, 65(1), 94–108.

- Marr, B. (2009). Managing and delivering performance. New York: Routledge.

- McDavid, J. C., Huse, I., & Hawthorn, L. R. L. (2013). Program evaluation and performance measurement: An introduction to practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Morrisey, G. L. (1976). Management by objectives and results in the public sector. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Poister, T. H., & Streib, G. (1995). MBO in municipal government: Variations on a traditional management tool. Public Administration Review, pp. 48–56.

- Rodgers, R., & Hunter, J. E. (1992). A foundation of good management practice in government: Management by objectives. Public Administration Review, pp. 27–39.

- Swiss, J. E. (1991). Public management systems: Monitoring and managing government performance. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.