CHAPTER ELEVEN

Performance Management in Grant and Contract Programs

In November 2013, President Barack Obama and his administration suffered an embarrassing blow in public opinion as his signature health care law, the Affordable Care Act, took effect. On October 1, the administration had just launched HealthCare.gov, the key Internet portal through which consumers could seek and purchase health insurance, to a host of debacles resulting from poor or incomplete system design and a lack of beta testing. The first few days were so bad—only six individuals nationwide actually purchased health insurance through HealthCare.gov on the first day—that the site had to be pulled down for extended maintenance, while the administration called in a blue-ribbon team of expert programmers and engineers from the top technology companies in the United States (Google, Red Hat, and Oracle) to help right the ship (FoxNews.com, 2013).

The contract with CGI Federal, a Canadian company filled with executives tied to a score of other botched government projects (Burke, 2013), was to build the web portal for HealthCare.gov. CGI Federal was confident six weeks prior to launch that the site would be fully functional in time for launch, but one week before launch in the “final ‘pre-flight checklist’…41 of 91 separate functions that CGI was responsible for finishing by the launch were still not working” (Goldstein & Eiperlin, 2013). It was estimated that the number of lines of code that needed to be rewritten for the site to properly function could be in the millions. In the fallout from the HealthCare.gov debacle, CGI Federal immediately began to shift blame to other contractors and to the federal government (Morgan & Cornwell, 2013). In the aftermath of the launch, it came to light that CGI Federal had been the contractor for Canada's national gun registry, a project plagued by cost overruns, delays, privacy breaches, and dysfunction. Canada spent $2 billion on a list that still doesn't work after years of effort (Miller, 2013).

Why did this project fail so miserably? What steps could be taken to limit the risks of failure? How can performance measurement and management help to ensure accountability when relying on external providers for public services? These are the questions this chapter addresses.

Government Versus Governance: Challenges of the Transition to Third-Party Implementation

Over the past three decades, a movement has been afoot to shift production of public goods and services from government to the private sector, including nonprofit and for-profit firms. The New Public Management movement prioritized privatization of production to achieve greater efficiency and effectiveness. While government continues to provide such public goods and services, production has shifted outward. Frederickson and Frederickson (2006) referred to this as the “hollowing out of the state” and reflected on the host of implementation challenges it poses. Contracting out allows the government to enjoy cost savings through economy of scale and increased efficiency. Moreover, the trend has enjoyed bipartisan support, though it was largely promulgated by Republicans as a mechanism that was thought to make government more efficient through the adoption of businesslike public management approaches.

Contracting out is one example of a broader pattern of evolving government service delivery approaches that move away from single agency provision toward provision through grant making, contracting, networks, partnerships, collaboratives, and other multiagency forms of service delivery. Public agencies are increasingly working with private for-profit and nonprofit organizations as well as other agencies across multiple levels of government to deliver services in a more efficient and more effective manner. Public managers face new accountability challenges in this environment, particularly because the linkages that characterized control and controllability in traditional bureaucratic models were hierarchical and direct, whereas controllability is increasingly weakened through vertical relationships and indirect service provision involving multiple principals. Naturally, when multiple partners are engaged in any enterprise, even the delivery of contract goods and services, performance becomes more difficult to monitor and performance management more challenging to implement and maintain.

This chapter explores the application of performance measurement and management in the context of indirect service delivery, particularly in the context of grant making and contracting out. In the provision of public goods and services, it has become customary for governments to rely on external producers to deliver services they provide. This occurs in various forms, such as partnerships, including public-private partnerships, collaboration, grant making, and contracting out. But one common feature of such arrangements is their reliance on contractual agreements to specify the terms of the relationship, including the nature of products or services to be provided.

Outsourcing and privatization occur at all levels of government. As an article in Governing related, “The search for financial salvation is sweeping the country as local governments grapple with waning sales and property tax revenues” (Nichols, 2010). But contracting out services is no panacea. Nichols (2010) identifies a few concerns that limit the effectiveness of contracting out public services:

- Agencies don't have metrics in place to prove in advance that outsourcing a service will save money.

- Poorly conceived contracts can create cost increases beyond the costs of in-house services.

- Poor contract oversight can leave a government vulnerable to corruption and profiteering.

Nichols concludes that “the privatization of public services can erode accountability and transparency, and drive governments deeper into debt.”

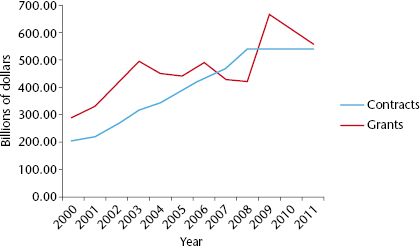

If we reflect on the extent to which this shift toward indirect service provision has occurred, a few numbers are worthy of consideration. Figure 11.1 reveals the level of US federal contract and grant spending by year. It highlights trends in both federal grant and contract spending over the past decade. Most notable in these trends is the fairly steady increase in both, the spike in grant spending as a result of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) following 2008, and a tapering off of spending in both categories as a result of fiscal restraint brought on by the pressures of debt limits, sequestration, and fiscal stress.

With the transfer of production comes the transfer of control and accountability, the central concern of this chapter. How does one maintain control or hold contractors accountable when they are not directly answerable to policymakers? One of the strongest arguments against contracting out government services is the failure of private producers to embrace broader public values in the delivery of services. Another is the inability to control firms and organizations not directly in the control of government hierarchy. In particular, political principals lose control over program administration, and thus outcomes, because the linkages of control are weaker in contracted governance than in internal production. Government officials are unable to influence private producers in the same way they can government officials because they are not in their direct employ.

This chapter provides a glimpse into the role that performance management plays in grant and contract administration from both the grantor and grantee perspectives. We first distinguish grant making from contracting, then explore the purpose of performance management to both parties (purchaser and producer) in such contractual arrangements. We raise a number of special considerations that influence the use of performance management in contracted governance. Finally, we conclude with a look at problems that public and nonprofit professionals attempting to use performance management in grant making or grant administration settings are likely to encounter. Throughout the chapter there is an emphasis on both the grantor/contractor and the grantee/contractee in the relationship. When general concepts are introduced, we adopt the terms purchaser and producer instead of terms specific to grants or contracts to indicate the relationship. The goals of each party are potentially different, leading to the sort of tension that has been frequently observed when performance requirements have been imposed in grant and contract settings.

Distinguishing Contracts from Grants

In the grand scheme of things, contracts and grants are not that different. Both are mechanisms that government uses to facilitate the provision of public goods and services it does not directly produce. A grant is essentially a contractual obligation wherein one party agrees to produce or provide a good or service and another agrees to pay for those services. We distinguish between a grant and a contract in the following manner: a contract is used when the product or service to be provided is clearly defined and readily available off the shelf in the marketplace. Performance in contracts can often be clearly measured through outputs such as airplanes delivered. A grant is used when a problem exists but no clear identifiable solutions are available. Here the emphasis of performance—the goals of the program—is on activities that will take place and their intended outcomes. In a contract, the emphasis is on the output to be delivered; in a grant, the emphasis is on the process—the activities that will take place—and the expected outcomes to be generated.

A contract is almost always more constraining than a grant because grants require flexibility in implementation to address various uncertainties in the implementing environment, the subjects of the service, or the activities to be undertaken. Contracts are consequently negotiated on a price per unit basis, whereas grants offer fixed spending for a proposed set of activities to maximize the desired outcomes for the available funding. Grant applications are consequently far more descriptive with respect to the activities to take place, whereas contracts offer little description of those activities, focusing instead on the characteristics, timing, and price of the outputs to be delivered. In the end, the differences between the two forms of government spending are minimal because both parties are obligated through their acceptance of a contractual document.

A second meaningful distinction between contracts and grants is the role of the principal in each case. In a contract setting, the principal is making an outright payment for a good or service with no financial obligation from the agent. In grant settings, however, the exchange of goods or resources is often viewed as assistance and involves financial commitment and participation from both the principal and the agent, and sometimes multiple principals and agents in more complex programs that characterize cooperative endeavors across agencies on a single project.

One cannot engage in a thorough discussion of grants without considering federalism, and one cannot engage a discussion of contracting out without some mention of intersectoral management. Grants are one of many policy mechanisms at the disposal of governments, and they are effective tools when funding and expertise are mismatched. In other words, higher-level governments (usually federal but sometimes states) have broader tax bases and access to financial resources. But need may be local, and problems may require local knowledge and expertise that are available only at the local government level. Grants offer a mechanism through which federal policy goals may be carried out in a distributed fashion across numerous local governments across the country. Over time, dependence on federal funding has grown, leading to overreliance by local recipients on federal funds and a loss of local policy control as federal priorities are pursued rather than local ones. These relationships have enabled the federal government to increase in power relative to state and local counterparts over time. Federalism refers to the relationship between the federal government and the sovereign states; the term intergovernmental relations extends the discussion to include local governments as well.

Contracting goods and services necessitates working across sectors, that is, with organizations in the public sector, the private for-profit sector, and the nonprofit sector interchangeably from setting to setting. This promotes a host of challenges, not the least of which is the potential for goal multiplicity and, potentially, goal incongruence. The for-profit sector will be concerned primarily with profit as a motivating goal. Nonprofit organizations will likely be focused on institutional goals, such as budget and staffing needs, but they will certainly be driven by mission-oriented strategic goals with respect to programming. Public sector organizations share these concerns, but they must also adhere to broader democratic and nonmission-based goals such as transparency. In addition, contracting loosens the bonds of hierarchy and increases the potential for information asymmetry, both of which require the development of new mechanisms to provide for accountability.

As the federal government has transitioned from a producer to a contractor, its capacity and function have also changed. Rather than experts with high levels of program-related expertise, government agencies are now staffed with experts in accounting and contract management; essentially they are administrative experts rather than program experts. Consequently they demonstrate considerable administrative capacity amid declining substantive capacity. To the extent such substantive capacity has declined on the part of principals in grant relationships, they are forced to rely more directly on traditional mechanisms of accountability such as audit and evaluation. They exercise close control on the disbursement of funds or the transfer of funds across budget line items. They follow protocols for technical and financial reporting and freeze accounts when reports are late or incomplete to ensure compliance. As administrative experts, they are disconnected from the program and activities; there is a weak bond of professional accountability because of the lack of program expertise; shared professional norms with program implementers do not reinforce program goals.

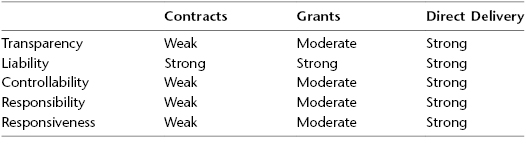

When technical program expertise exists at the agent level but not the principal level, there is potential for information asymmetry, which allows agents to use greater discretion in program implementation. To summarize, the transition from involved participant to sterile administrator has implications for the dimension of accountability that is emphasized. If we think in terms of the five dimensions of accountability posed by Koppell (2005), we see that grant making and contracting are quite different from direct government service delivery (table 11.1). Notably, direct service delivery offers stronger accountability in each of the five dimensions than does indirect delivery through grants or contracts.

Table 11.1 Accountability Relationships under Different Delivery Mechanisms

Performance Measurement and Management in Grants and Contracts

The idea of performance contracting is not new. And over time, the performance requirements of contracts for standard services have become increasingly specific, addressing not only outputs but processes and not only quantity but quality. One example we find is in state highway contracts. Having dealt with projects that suffer considerable delays, states began to improve contracts to incentivize timely completion. To do so, they included performance clauses that focus on the timing of completion relative to the projected completion date. Where favor may be given to a contractor that promises to complete the project more quickly during the bid process, contractors face a moral hazard to promise more than they can deliver during the proposal process. Imposing penalties for delays in the contract helps to alleviate this problem. Likewise, adding performance bonuses for early completion minimizes disruption to the transportation system where projects can be completed ahead of schedule.

With respect to quality control, states routinely drill random core samples from newly constructed road projects to verify the composition, quality, and thickness of various layers of pavement that have been applied. Where roads and bridges have been specifically engineered, states must verify conformity with design in order to ensure public safety. For projects of this nature, it is now commonplace for contractual obligations to extend beyond the direct outputs to be delivered to also include secondary, or nonmission-based, aspects such as public safety. In other words, aspects of process are also managed, such as the use of safety mechanisms to protect both motorists and workers. Concrete barriers, signage, and barrels add to the cost of delivering the new road surface, but they are necessary to ensure safety, and failure to meet these process-based requirements could result in termination of a contract.

Grants are entirely different. In order to truly understand performance measurement within grant management, it is necessary to understand the differences in types of grants available. Grant types run a wide gamut from those in which the use of funds is highly constrained to those where the use of funds is subject to recipient discretion. Government grants were once characterized as categorical or noncategorical, where categorical grants were limited to use for particular functions and noncategorical grants were unrestricted in their use (Hall, 2010). Noncategorical grants, such as general revenue sharing, are a thing of the past. The most common categorical grant types include formula, block, and categorical, or project, grants. Over time grants have become more restrictive in general, buckling under the weight of considerable conditions, some of which are tied to the grant purpose and some of which focus on nonmission-based aspects of the recipient's work.

Formula grants offer the greatest flexibility in spending, as they support broad or general purposes. One example is federal funding to support public schools. Funds are allocated using a formula based on the number of students and student attendance; these funds support general operation of the school—personnel, equipment, capital, supplies, and so on. There are restrictions on the use of funds, but the recipient school has wide discretion in using them.

Block grants, like formula grants, have traditionally offered discretion to recipients within a categorical spending area. For example, in the category of community development, the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program has become one of the most widely known federal block grant programs. It makes available lump sums to states and entitlement cities, the use of which must simply be tied to a list of allowable project types and uses.

Finally, categorical project grants are the most restrictive of grant types. These grants fund a specific project for a specific period of time, and the use of funds is limited to the activities described in the proposal. Project grants might be used, for example, to build a senior citizens center or to rehabilitate a public housing development. They are used to develop sites for economic development projects or to fund vocational training programs in areas of targeted need. Project grants cover various activities across the gamut of federal agencies. They range from small technical assistance programs with $25,000 limits to massive projects in excess of $1 million. Project grants are tightly monitored to ensure compliance with the proposed activity and are the most restrictive grant type used. Over time most grant funding has shifted away from less restrictive forms toward project grant funding.

The differences highlighted so far typically characterize government grant types. When we look at foundation or corporate giving programs, there are similar distinctions. Categorical project grants characterize most of the funds awarded by foundations, especially to the extent they are competitive awards. That is, foundations have a strong interest in the outcomes to be delivered, and they work closely with grantees during implementation not only to ensure compliance but to offer substantive program assistance and participate in the learning process. These programs are closely monitored through reporting and audit just like their government counterparts. Some foundation giving and most corporate giving, however, is granted for general support of the organization with no strings attached, making it more like the noncategorical grant form. Such support comes with few strings attached and usually no monitoring or performance assessment. There is no longer a governmental counterpart to this type of assistance, though it would be similar in nature to general revenue sharing where funds were awarded with no restrictions on use.

Hall (2010) characterizes conditionality as an inverse relationship where increasing grantor conditions reduce local discretion. As a result, the efficacy of performance measurement and management will depend on the underlying purpose of the program. If federal (grantor) intent is to provide greater implementing flexibility for grantees, then performance measures must be flexible, or they might even be process-oriented measures that could capture the degree to which flexibility or discretion is preserved. These conditions, or strings, typically come in the form of matching requirements and restrictions on expenditure. Hall (2010) thus characterizes grant types on a spectrum ranging from unconditional to conditional and notes that the trend of conditionality is increasing in federal programs.

The method of allocation distinguishes among the grant forms as well. Formula grants are awarded on the basis of predetermined criteria on a formula basis, as are entitlement block grants. Project grants are awarded on a competitive basis. More and more grants take the competitive method of allocation and increasing conditions, consistent with greater targeting of effort to meet clearly defined goals.

While performance measurement may seem more straightforward in categorical or block grant programs, it also can play a role in formula grant programs. In fact, performance measurement can be central to the allocation of formula-based resources. It is often performance that justifies a recipient to qualify for assistance and that sets the amount of assistance. So without performance measurement, the formula would not function at all.

Let's consider one brief example: the Federal Transit Administration's Small Transit Intensive Cities (STIC) program, which makes grants to public transit systems in small urban areas that meet or exceed targets on selected performance measures. Those targets are established by taking the average performance of transit systems in larger urban areas on selected measures. STIC uses six performance targets: passenger-miles per vehicle-revenue-mile, passenger-miles per vehicle revenue hour, vehicle-revenue-miles per capita, vehicle revenue hours per capita, passenger-miles per capita, and passenger trips per capita. Notice that these indicators are all ratios, and they are all relative, so that if a shock occurs to the economy that has an adverse impact on ridership in large cities, the targets automatically compensate. Four of these measures heavily emphasize ridership, and the other two take service levels into account.

These differences are important to any consideration of performance management for two reasons. First, it is difficult to prescribe performance measures when the use of funds is itself neither restricted nor known, nor tied to specific outputs or outcomes. It violates the SMART principle for indicators—specific, measureable, ambitious, realistic, and time-bound—to adopt general measures. Second, performance measurement itself must conform to the purpose of the program. It is not realistic or necessary to assess specific performance outputs or outcomes for a program that is intended to preserve local spending discretion. Nonetheless, calls for accountability, and the adoption of government-wide performance management systems like the Government Performance and Results Act or the Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART) have imposed square peg solutions on the round hole of these more discretionary grant types. These have been met with implementation difficulty, frustration from recipients and grant program managers, and criticism of programs by political elites. The experience of CDBG offers a telling example of this trend (Hall & Handley, 2011).

The CDBG program is a longstanding federal block grant program situated within the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The funding source has become a mainstay for state and local governments to support their community and economic development goals because of the considerable spending flexibility the grant offers. During the George W. Bush administration's tenure, PART was used to assess the extent to which almost one thousand federal programs were meeting their strategic goals. CDBG earned a PART rating of “Results Not Demonstrated,” ultimately leading President Bush to issue a major legislative proposal to reorganize eighteen of the federal government's economic development programs, including CDBG, into one larger program (to be called the Strengthening America's Communities Initiative). The new program would consolidate these programs within the Economic Development Administration at a significantly lower total budget. The proposal was met with resistance from Congress and never passed, in large part due to widespread dissent from state and local government officials who relied heavily on the flexible funding to support their own local objectives.

In 2006 PART reported that CDBG contained inadequacies, including an unclear program purpose; an inability to address the specific stated problem of revitalizing distressed urban communities; a lack of targeting efforts to reach intended beneficiaries; a lack of long-term goals and performance measures to focus on outcomes; inadequate collection of grantee data in a timely, credible, and uniform manner; and an inability to provide public access to these data in a transparent manner (Center for Effective Government, 2006).

HUD nonetheless began to force CDBG to comply with the strategic planning and performance assessment goals of PART, reining in grant recipients by requiring them to demonstrate the connection of each funded local project to federally determined strategic goals. Hall and Handley (2011) characterize CDBG's history with performance measurement and reporting as ineffective and riddled with problems. Their research reports the problems encountered with the most recent implementation of performance measurement in CDBG. They find that local officials found the new requirements to be unworkable and to create an unnecessary administrative burden.

There are multiple lessons to be gleaned from this example. As Hall and Handley (2011) note, “A program with such diverse recipients and such broad functional areas provides a lesson for more effective implementation of future performance measurement initiatives” (p. 445). First, it is possible to measure the performance of grant programs, but the flexible design and discretion inherent in block grant programs preclude strict enforcement of grantor goals. Second, when grantor goals are contractually or administratively enforced, the net effect is reduced discretion for grantees, which may defeat the original purpose of the flexible program design. And finally, should that occur, the reduced flexibility may result in reduced grantee demand for grantor funding for the stated purposes as they lead grantee efforts further and further away from local priorities and toward grantor priorities. In particular, Hall and Handley found that local CDBG administrators who reported that the new CDBG regulations limited their city's CDBG mission were found to have significantly decreased satisfaction with performance measurement.

Hall and Handley (2011) also found that CDBG programs that received training or technical assistance on performance measurement from HUD, those with stronger relationships with HUD regional offices, and those receiving monitoring visits had increased satisfaction with the performance measurement effort. The light at the end of the tunnel is simple: even with flexible programs, where focus has traditionally been on activities and outputs rather than outcomes, the application of a clear process supported with training and development of performance measurement capacity can lead to successful implementation of performance measurement. The net effect of such a shift is greater responsiveness to federal program goals and stronger accountability in this dimension. Still of concern, however, is the problem associated with grantor/grantee goal incongruity in such programs. With strong performance measurement in place, grant recipients will be forced to conform closely to grantor goals or make the difficult choice to forgo funding. As Hall and Handley (2011) conclude, “Local administrators' lack of satisfaction may derive not just from the performance measures, but from the tension the measures create by increasing administrators' awareness that they are agents of local and federal principals with incongruent goals” (p. 463).

Contract Performance Management

Problems with procurement from third parties can result from two sources. One is weak or nonexistent procurement policies, including contract management. For example, contracts require sound practices to ensure accountability and prohibit waste or fraud. The first element of successful procurement is competition, which is generally attained through competitive bidding. The second is the elimination of bias, often established by identifying the criteria on which the award will be granted in advance and by blinding the identity of the bidders during the evaluation process. Third, it is necessary to clearly specify the goods or services to be solicited. Qualitative differences in products could lead to lower contract bids with less effective outcomes when the deliverables are not clear and consistent. Fourth, a clear basis of payment should be established in advance so as to ensure that payment is made only if deliverables are produced according to the agreement in both quantity and quality and in terms of timing. And a fifth premise of effective procurement is that production be monitored to validate quality control on an ongoing basis.

When we consider the opportunities for performance management with respect to indirect services like contracts, there are some clear parallels with direct service delivery but also some clear challenges. First, consider the simplicity of the logic model in contractual circumstances. Inputs are known insofar as procured services are within the available annual budget appropriation. Specification of contractual deliverables is actually identifying outputs. As contracting practices advance and partnerships become more elaborate and long term in nature, it is possible to move beyond simple outputs toward outcomes in some fields of practice. For example, when a state cabinet for families and children contracts for the management of services for individuals with developmental disabilities, the outcome of interest is providing for their health, economic security, and, insofar as possible, a high quality of life for individuals in the state's care. Attending to outcome performance is better aligned with program interests in this case than output performance because it provides greater flexibility to the contractors to determine and provide for individual needs and limits the incentive to game the system by generating unnecessary outputs, such as medical visits or behavioral evaluations.

In contract settings, the activities portion of the logic model may be handled in a few ways. If the process matters to outcome quality, activities may be specified in some detail in the contract. Highway contracts are a good example of this because they must fulfill engineering designs and standards to ensure public safety. At the other extreme, the purchaser may simply opt not to specify processes, choosing instead to leave strategy up to the producer. And in the way of a middle ground, the purchaser may choose to place limitations on strategy by prohibiting certain practices or limiting practice to a range of options.

The program goals and objectives must be established in advance with contracted goods and services because they are elements of the contract terms. But it is all too easy to set aside the obligation to monitor contract performance. In other words, if responsibility for producing public goods and services is exported, in whole or in part, to private firms or partner organizations, it is easy to assume that the responsibility for performance is transferred to the producer. That approach is naive, however, because producers are often motivated by profit or other goals rather than the public goals of equity, fairness, efficiency, and effectiveness. Performance monitoring is essential for in-house services, and so equal care should be taken with externally procured goods and services. It is necessary to examine the progress that producers are making with contracts they have been awarded to identify problems early on and endeavor to correct them before they evolve into more significant debacles.

To this end, it is important that an agency adheres to the SMART approach to identifying performance measures: specific, measurable, ambitious, realistic, and time-bound. Measures used to track contract performance should be tied directly to the program goals and objectives and should be readily observable and quantifiable. A monitoring plan should be in place to ensure that performance is tracked in a meaningful time frame and at an appropriate level of detail or aggregation. This information, of course, should be reported to appropriate managers, personnel, and stakeholders in a timely manner so that it can influence program management decisions. The issue with respect to measuring performance that is taking place in another organization is transparency. There has always been an information asymmetry between principals and agents within hierarchical organizations, and the same is true in contractual relationships. The producer, as the agent, has information that will be difficult for the purchaser to discern. The expectation of transparency will be lessened to the extent that efforts occur within private organizations.

In terms of responsible contract management, it is important to recognize that there are multiple forms of contracts designed to accommodate different needs. A competitive contract is used when there are multiple suppliers that can generate price competition. In some cases, time is of the essence, and so contracts may be let with fewer safeguards in place, preferring rather to use local suppliers that can act quickly. For example, when a mudslide closes an interstate highway, bottlenecking commerce and travel, a highway department might issue a noncompetitive contract to local firms to clear away the spoils and shore up the disrupted area. In other cases, there is a call for open-ended contracts where the deliverables are not clearly specified. For example, technical assistance may be needed, and so consulting contracts may be let for a specified number of hours at a particular rate to address problems not yet identified. And finally, there are some situations where the complexity of the problem itself limits the pool of potential bidders, often resulting in no-bid contracts.

In 2005 the US Army Corps of Engineers sought to issue a contract to repair the ailing Wolf Creek Dam that impounds Lake Cumberland in southern Kentucky. The dam was deemed at high risk of failure, which would have brought significant long-term economic distress to the region, not to mention the potential downstream flood damage in Nashville, Tennessee, situated on the Cumberland River. A global solicitation ultimately resulted in a $594 million contract issued to a partnership between two European firms (Treviicos-Soletanche, JV) formed explicitly to respond to the revised request for proposal, and construction began in March 2006 (US Army Corps of Engineers, 2013). In this case, the contract was awarded on the basis of expertise, not cost (Mardis, 2008).

In the way of perspective, “federal agencies awarded $115.2 billion in no-bid contracts in fiscal 2012, an 8.9 percent increase from $105.8 billion in 2009, even as total contract spending decreased by 5 percent during the period” (Hickey, 2013). Ironically, this jump followed President Barack Obama's 2009 promise that his administration would reduce “wasteful” and “inefficient” no-bid contracts and “dramatically reform the way we do business on contracts across the entire government” (Hickey, 2013).

The manner in which performance is tracked during contract implementation can range in sophistication from inputs to outcomes. This, of course, corresponds to similar observations in direct service delivery where better measures are outcome oriented. The simplest mechanism for tracking progress also reveals the least information about progress toward goals. The focus on inputs—often measured as dollars paid or the proportion of the total contract amount expended—is such an ineffective measure. A contractor can bill for services provided, leading to the impression that progress is being made, while in fact the work may be of poor quality or not in keeping with the expectations of the contract. In the Corps of Engineers example, such a performance measure would be indicated by the running total of funds expended or the proportion of the total contract amount expended to date. Again, this sort of measure provides opportunity for gaming and does not clearly identify key outcomes of interest.

Performance measures could relate to outputs as well such as personnel-hours of work completed or cubic yards of concrete poured. But these also fail to reflect the true outcome: the stability and safety of the dam. Performance could be tracked by identifying key milestones—objectives that represent significant achievement toward project completion. In other words, they provide information with meaning rather than just data. In the case of the dam rehabilitation, this might include phases of the project, such as preparation of the work platform; grouting work in the porous, cavernous rock beneath the structure; drilling of the secant piles; and pouring concrete for the final barrier wall. And finally, outcome measures could be used, such as readings from instruments designed to detect material shift within the structure, reductions in which would reveal improved safety. This is all to say that measurement in contract settings can be as simplistic or sophisticated as in direct service delivery, and better performance measures will provide better information to decision makers.

Ultimately the characteristic of contracting that permits increased accountability is the ability to tie payments to performance objectives. These instruments have become increasingly complex over time, for example, assessing penalties for substandard services or products, penalties for late delivery, and even bonuses and incentives for early completion. Performance contracts, though, require commitment to measurement and capacity to observe and measure the key elements of production and product quality.

Performance contracts have become commonplace in the public sector across levels of government and functions. In Hawaii, the legislature authorized the use of performance contracts to collect delinquent taxes in 1996. The following summarizes the requirements:

A contract under which compensation to the vendor shall be computed according to performance standards established by the department. Any performance-based contract entered into by the department for such purpose shall provide:

- For the payment of fees based on a contractually specified amount of the increase in the amount of taxes, interests, and penalties collected and attributable to the implementation of automated tax systems; or

- For the payment of fees on a fixed-fee contract basis to be paid from the increase in the amount of taxes, interest, and penalties collected and attributable to the implementation of automated tax systems. (Auditor of the State of Hawaii, 2010, p. 8)

As an example of how important contract provisions and management can be to agency performance, consider the following excerpt from the Hawaii Auditor's Report, demonstrating the breakdown of the requirements (the contractor is the same firm contracted to develop HealthCare.Gov):

In this environment of discord, the department modified the Delinquent Tax Collections Initiatives contract. We found that this 2009 modification was crafted independently by a former deputy director with no formal IT background or training. It removed the obligation of the vendor to complete the 2008 contract's 22 initiatives as well as a constraint limiting payment to the vendor to $9.8 million for work on the 2008 contract. Instead, the 2009 modification allowed the vendor to receive the remaining compensation of $15.2 million from new collections without first completing deliverables from the 2008 contract. In addition, the modification also deleted contract provisions that removed the department's ability to hold the vendor accountable for defects and system integration problems. (Auditor of the State of Hawaii, 2010)

This example reveals how lax contract management resulted in weak accountability on the part of vendors providing delinquent tax collection. It shows as well the importance of establishing clear performance measures and a clear performance measurement framework, and monitoring performance on an ongoing basis, even in contracted programs where service providers are contractually bound. Failure to monitor and provide oversight is a recipe for poor performance results.

In the case of Hawaii's delinquent tax collection contracts, significant changes occurred in 2009 that weakened accountability and performance (Auditor of the State of Hawaii, 2010). Under 2008 contract initiatives, performance (and payment) was assessed according to the completion of specific initiatives—activities—that were expected to lead, according to the program logic, to the desired outcomes. These twenty-two initiatives included, for example, automated address updates, risk modeling, a virtual call center and automation of collection calls, and collections business process improvements (Auditor of the State of Hawaii, 2010). But rather than improving, the system took a turn for the worse the following year.

A stronger system would have emphasized performance levels and institutionalized monitoring receipts of delinquent taxes. In this case, vendor performance could have been assessed using simple outcomes like the dollar value of delinquent taxes collected, the proportion of delinquent tax dollars collected, or breakouts of either measure by groups (such as business versus personal or residents versus nonresidents). Other measures might have focused on the number or proportion of delinquent accounts brought into compliance. Examining these data over time would have provided a ready check on the extent to which the contracted vendor was generating the desired outcomes and allowed time to make amendments or corrections.

Purpose of Performance Measurement in Grant and Contract Management

One guiding principle in performance measurement in grant or contract settings is that the parameters of the system will be determined primarily by whether one is the purchaser or the producer. Furthermore, purchasers' and producers' perceptions of the system will be colored by whether the system was developed internally in a bottom-up fashion or imposed externally or in a top-down fashion. The purpose will vary along this dimension, and so will the measures and processes established. External interests will focus on accountability, but the dimension emphasized may be controllability rather than responsiveness. Internal interests will likely focus on responsiveness and performance improvement. It is important to think along these differences as we examine performance management in grant and contract management settings.

The role of performance management in government has a number of possible dimensions. Behn (2003) identified eight, with an emphasis on improvement. In contracted settings, however, the contract or grant is negotiated in advance. The end results are specified, as is the time line for completion, and the role of government managers becomes one of oversight and enforcement. If the prescribed outputs are not delivered, payment is withheld. As such, there is no consideration on the part of either party for delivering more than has been negotiated in a contract setting. Program officers overseeing grant projects face similar dilemmas. Their role is one of oversight and enforcement of the proposed time line of activities. Outcomes are not guaranteed, so their focus is on implementation and ensuring consistency with the process described in the proposal, not with the traditional forms of accountability expected in public performance management. When the time is up, either the contract or grant has been fulfilled or it has not.

We can argue, then, that the purpose of performance management in grant and contract programs is one of ensuring conformity with the written agreements that set them into motion. The obligations of performance measurement will be weightier under grant management than under simple contracting. Grant making and contracting has been viewed as a top-down enterprise, and emphasis on performance management is naturally on the funding entity. However, in the case of contracting and grant making, it is now necessary to reflect on the role of not only the funder but also the recipient. The vast majority of grants are made from the federal government to state and local governments that may be operating their own performance management systems independent of any federal requirements. Likewise, nonprofit agencies have shown increased acuity in the use of performance measurement to demonstrate their effectiveness. Where these organizations are recipients of grants or contracts, they may find a meaningful role to play in measuring performance, and they may also find that the expectations of the funder do not align with their existing systems, processes, or structures.

Public managers in contracts may be obligated to ensure quality control, and report on quality, with the expectation that any substandard products or services will not be reimbursed. Public managers in grant programs, though, may be obligated to track and monitor performance on inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts. This stems in part from the desire to identify programs that work and may be systematized over time into formal programs.

Performance-Based Grant Management

Recent trends in federal grant administration reveal a heightened focus on performance-based grant management. In light of the performance emphasis that pervades federal administration, this should not come as a great surprise. Two examples reveal the extent to which performance measurement has become central to the administration of grant funding programs in the United States. First, we explore the significant change brought about with implementation of the ARRA. Second, we explore the unique case of the US Centers for Disease Control's (CDC) National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP).

The ARRA heralded a new approach to accountability in grant administration. The funding mechanism itself is not unique, especially considering that the funds were funneled through existing grant programs that Congress had previously authorized. ARRA was nevertheless unique in two ways. First, its sheer magnitude causes it to stand out amid the crowd of funding programs. Second, program implementation came with a strict concern for accountability brought about through three distinct mechanisms: performance measurement requirements that extend not just to grantees but to all subgrantees or contractors receiving funding from the program, clear goal orientation focused on jobs created or saved, and transparency through reporting of key funding and performance statistics for all awards, searchable by geography, program, or recipient. The web portal created for this program (www.Recovery.gov) did not use unique approaches but recombined them in a more effective manner that brought heightened attention to performance throughout the process (Hall & Jennings, 2011). It is interesting, though, that the intensive performance measurement and reporting focus was limited to the simple outputs and outcomes all awards had in common, while performance on the traditional mission-oriented focus of the programs went untracked, at least by the centralized repository.

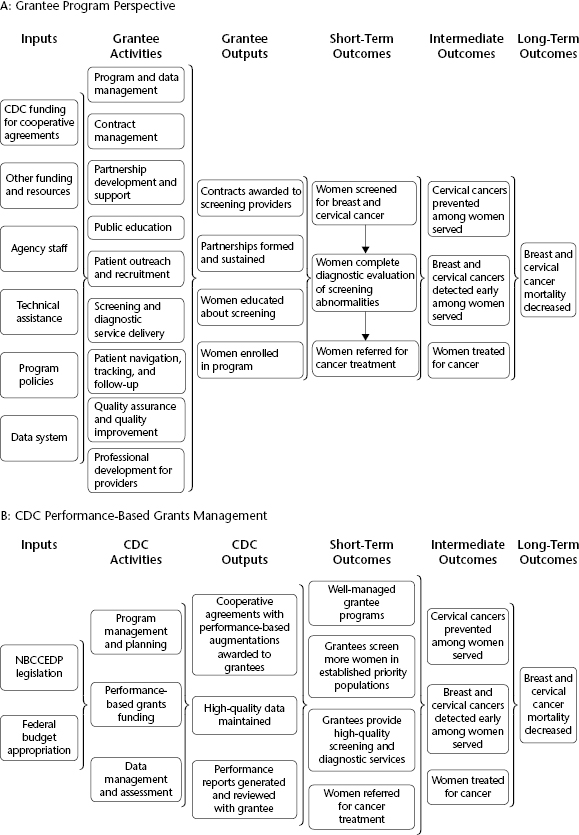

The other example reveals how one program has not only used performance measurement to monitor key program outcome performance but tied performance to the allocation of grants. The CDC's NBCCEDP was created in 1990 to reduce morbidity and mortality due to breast and cervical cancer among medically underserved women. The program provides grant funding to health organizations in sixty-seven states, tribes, and territories; in 2013, nearly $150 million was allocated, with individual grants ranging from about $250,000 to over $8 million. These grantees contract with local health care providers for clinical service delivery and manage program data at the state, tribe, or territory level. Critical outputs for the program include women receiving quality screening and diagnostic services and referrals to treatment. Ample research has shown that these cancers can be prevented or treated more effectively when detected early, which directly links these outputs to the intended program outcomes (reduced morbidity and mortality among the target population) in the program logic model.

In 2005 NBCCEDP adopted a performance-based grant management system. Figure 11.2 presents the program logic from two perspectives—that of the grantee (panel A) and that of the grantor agency perspective (panel B) under this new system. Performance is assessed on twenty-six indicators, of which nine are central to the agency's data review process; these are key performance indicators that represent essential dimensions of performance. Performance information has been collected since the inception of the program, but with the adoption of the performance-based grant management system in 2005, the data were for the first time used to establish targets and linked to grants. As part of the semiannual data review, a summary report of the core measures is prepared and discussed by CDC and the grantee. This is made possible by the consistent grantee pool and stable geography. In other words, the performance measures are comparable over time because there are longstanding grantees serving the same service areas.

Source: US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Used with permission.

In panels A and B in figure 11.2, we see two unique perspectives that reveal the logic of how outcomes are realized. Panel A shows the grantee perspective; grantees are the organizations receiving federal grant funds in exchange for the services they provide or goods they produce. In this case, panel A shows the federal grant funds (received through the cooperative agreements) as inputs. The activities are focused on the substance of the program—delivering services. In panel B, we see program management from the administrative perspective, that is, the point of view of the grant-making agency. Here inputs are the legal constraints within which they must work, and activities are focused on the allocation of grant funds and management of cooperative agreements.

The outputs of the substantive process (panel A) focus on developing partnerships and establishing contracts with providers, and education and enrollment of women in the program for grantees. The outputs focus on administrative matters (panel B) for the grantor: cooperative agreements, data maintenance, and performance reporting drive outputs for the grantor agency. Notice, though, that when it comes to outcomes, the two models converge: both are working toward the same end goals, but their individual agency processes for doing so are unique. By mapping program logic in such a fashion, it becomes easier to understand how organizations bring about their results in a collaborative fashion. Similarities emerge in short-term outcomes, and in this case, the intermediate and long-term outcomes are identical between the two approaches.

Responsibility for performance, then, can be clearly attributed to the grantee and measurement over an extended time period is possible. The grantee's achievement of the established targets constitutes the criteria used to determine incremental changes in the grant amount. The targets are realistic and take measurement difficulties into consideration; the final targets are informed by medical expert opinion, stakeholder input, and the realities of program implementation. Program performance has been high overall, making it difficult to distinguish high performers from low performers within the program. In the case of this program, the implementation of performance-based grant management likely had little effect on overall performance because the targets set were already being met, were unambitious, and funding levels were at rates associated with achievement of the targets (Poister, Pasha, DeGroff, Royalty, & Joseph, 2013).

The challenge of such a performance-based grant management system, as with all other performance budgeting efforts, is that there is a subjective element to the funding allocation process. Objectively, better performance is associated with an expectation of higher funding, but there are certainly situations where this assumption would not be supported in the political arena. For example, when performance is high, the problem may be reduced, leading to a reprioritization of spending toward problems that are seen as needier. Moreover, in cases where performance is lower than expected, it may be the case that insufficient resources were available, calling for an increase in funding. While objective allocation of grants based on performance is a rational approach, it may not be appropriate as the sole allocation criterion in every instance.

Another example of innovative incorporation or performance measurement into grant administration comes from the Office of Rural Health Policy and, more specifically, the Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility (FLEX) program. The FLEX monitoring group team is conducting a performance monitoring effort for the program to assess its impact on rural hospitals and communities and the role of states in achieving program objectives. The core of this initiative is a strong emphasis on the development of logic models that define linkages among resources, outputs, and outcomes and that facilitate the development of strong and meaningful measures of performance that can be tracked over time. Because the program focuses on state rural health plans, it is not strictly possible to establish federal standards for performance that would be appropriate to each state setting. The approach developed here, rather, is to focus on strong performance measurement within states by systematizing a strong performance measurement process that is able to track and report outcomes.

Other examples of performance-based grant management exist, and the incorporation of performance information into the application and funding allocation process is a key way to use performance information in decision making. Building performance targets and other requirements into grant awards is another way. And finally, institutionalizing performance measurement and reporting expectations for grant-funded programs is a key approach to building more performance-oriented grant management. These changes are taking place not only in the public sector through federal grants but also through major nonprofit organizations and foundations. It is not uncommon for foundations to request information on past performance as part of their request for proposals. In one major national example, the United Way recently revised its approach to making local funding decisions by requiring applicants to document their achievement of past strategic targets and setting aside points in the application review process for past success.

Problems and Special Considerations Using Performance Management in Grant Programs

When it comes to grant management, federal requirements have become a point of concern. The list of conditions to which a grantee must agree to adhere is ominous and ever expanding. These conditions are often not directly tied to the strategic program mission, but to other nonmission-based considerations. When it comes to accountability, documenting compliance for these conditions constitutes a significant administrative burden for grantees. Similarly, ensuring compliance with these conditions requires capacity and resources for the grantor agencies as well. Attention to these nonmission-based elements of program performance necessarily adds to the indirect costs of program administration and detracts from the efficiency of program delivery. Similar contractual conditions exist or can be incorporated.

The lesson is that those things that matter can be incorporated into the agreements that govern grant awards and contracts. If performance on mission-oriented strategic goals is important, performance requirements such as targets can be identified from the start, as can performance measurement and reporting expectations. It is equally possible to add a variety of nonmission-based considerations, including requirements to document performance with respect to those goals. Conditions have come under greater scrutiny by applicants, leading many to forgo federal funding to avoid the administrative burden and, ultimately, conformity with federal goals as opposed to local preferences. In many cases, such resistance is symbolic and temporary, such as Texas's refusal to accept federal stimulus funds (Condon, 2009). In others, such as Hillsdale College, federal funds come with conditional expectations that violate the institution's core values (Hillsdale College, 2013). For recipients of grants or contracts that accept the conditions and goals of the grantor or contractor, there is risk of mission creep over time away from those things deemed to be strategically important locally toward values or goals considered to be important by the funding agencies.

In a granted or contracted work environment, there are two levels of management. The purchaser is mostly interested in policy-level matters, whereas the producer is more concerned with day-to-day management. In networked collaborations, there may be multiple participants with further divergent goals and interests. Where multiple principals exist, the potential is strong for multiple goals that often find themselves in conflict. In these settings, it becomes a question of what to measure. The strictest constraint on performance measurement and management is resource availability; it takes time and effort to measure each additional indicator, and as the list of indicators grows, so grows the complexity associated with interpreting performance information. The trade-off becomes whether to develop a parsimonious model that would be useful to guiding implementation and management or an expansive model that incorporates the interests of all involved parties. When goals are not aligned, this effort may exacerbate the underlying conflict. When goals and outcomes are consistent and uniform from place to place, it may be easier to institutionalize measures and indicators from the top down. But collaborative settings are typically unique, precluding such a possibility.

Grant management has typically been about conformity to the process described in the scope of work provided in the application document. Quarterly technical reports are usually required to substantiate progress in implementing the proposed work plan. With many grant programs, particularly those that are categorical and competitive, the grant will have expired before outcomes have been realized. The contractual obligation between grantor and grantee would have been met, with no requirement or expectation to examine or report the extent to which the program actually realized its intended outcomes. In this way, the short time horizon of many grant programs limits the potential for performance measurement and management. Of course, where recipients and funders interact in repeated iterations on different projects, this information can be taken into consideration as a condition for future funding. The net result is a reluctance of agencies to focus on outcome goals in grant programs, preferring to focus on elements of process such as quality control and measures related to activities instead of outcomes.

References

- Auditor of the State of Hawaii. (2010, December). Report 10–11. Management and Financial Audit of Department of Taxation Contracts. http://files.hawaii.gov/auditor/Reports/2010/10–11.pdf

- Behn, R. D. (2003). Why measure performance? Different purposes require different measures. Public Administration Review, 63, 586–606.

- Burke, C. (2013, November 15). Obamacare contractor linked to 20 troubled government projects. Newsmax.com. http://www.newsmax.com/Newsfront/cgi-obamacare-ams-mishandled/2013/11/15/id/536988

- Center for Effective Government. (2006). OMB's 2006 PART performance measurements for community development block grant. Washington, DC. http://www.foreffectivegov.org/node/2436

- Condon, S. (2009, July 16). Texas gov. who refused stimulus funds asks for loan. CBSNews.com. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/texas-gov-who-refused-stimulus-funds-asks-for-loan/

- FoxNews.Com. (2013, November 11). ObamaCare website contractor previously cited over security lapses. http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2013/11/01/obamacare-website-contractor-previously-cited-over-security-lapses/

- Frederickson, D. G., & Frederickson, H. G. (2006). Measuring the performance of the hollow state. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Goldstein, A., & Eiperlin, J. (2013, November 23). HealthCare.gov contractor had high confidence but low success. Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/healthcaregov-contractor-had-high-confidence-but-low-success/2013/11/23/1ab2c2b2–5407–11e3–9fe0-fd2ca728e67c_story.html

- Hall, J. L. (2010). Grant management: Funding for public and nonprofit programs. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

- Hall, J. L., & Handley, D. M. (2011). City adoption of federal performance measurement requirements: Perspectives from community development block grant program administrators. Public Performance and Management Review, 34, 443–467.

- Hall, J. L., & Jennings, E. T. (2011). The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA): A critical examination of accountability and transparency in the Obama administration. Public Performance and Management Review, 35, 202–226.

- Hickey, J. G. (2013, November 14). No-bid contracts mark Obama administration. NewsMax.com. http://www.newsmax.com/Newsfront/Obama-administration-no-bid-contracts/2013/11/13/id/536496

- Hillsdale College. (2013). Financial Scholarships, grants, and loans. http://www.hillsdale.edu/aid/scholarships

- Koppell, J. G. (2005). Pathologies of accountability: ICANN and the challenge of “multiple accountabilities disorder.” Public Administration Review, 65, 94–108.

- Mardis, B. (2008, July 25). Corps: Construction firm selected on merit. Commonwealth Journal. http://www.somerset-kentucky.com/local/x681548612/Corps-Construction-firm-selected-on-merit

- Miller, E. (2013, November 6). How Obamacare contractor bungled Canada's gun registry. Washington Times. www.washingtontimes.com/news/2013/nov/6/miller-before-obamacare-a-record-of-failure/?page=all

- Morgan, D., & Cornwell. S. (2013, October 23) U.S. Contractors shift blame for Healthcare.gov problems. http://news.yahoo.com/cgi-blames-another-contractor-healthcare-gov-bottleneck-211848670—sector.html

- Nichols, R. (2010, December). The pros and cons of privatizing government functions. Governing. http://www.governing.com/topics/mgmt/pros-cons-privatizing-government-functions.html

- Poister, T., Pasha, O. Q., DeGroff, A., Royalty, J., & Joseph, K. (2013). Performance based grants management in the health sector: Evaluating effectiveness in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unpublished paper.

- US Army Corps of Engineers. (2013). Wolf Creek Dam Safety Major Rehabilitation, Ky: Fact Sheet. Washington, DC: US Army Corps of Engineers. http://www.lrn.usace.army.mil/Media/FactSheets/FactSheetArticleView/tabid/6992/Article/6242/wolf-creek-dam-safety-major-rehabilitation-ky.aspx