CHAPTER 5: THE PILOTS OF 161 SQUADRON

The men who flew the Lysanders (‘A’ Flight) of 161 Squadron were a select few. At any given time, they would number no more than five and, throughout the years between October 1940 and August 1944, when the moonlit operations were run from Tangmere, only thirty-five pilots were involved in total. It meant, of course, that they were a close-knit team, living at close quarters, particularly during the moon periods at Tangmere and learning off one another’s experiences, both good and bad. Each must have felt a sense of utter loneliness every time they set off into the night to pick their way across a dark and hostile terrain towards their unmarked target. Even when an operation involved two or three Lysanders at a time, they could not follow a leader but had to find their way on their own.

Hugh Verity, who commanded the Lysander flight for the whole of 1943, its busiest year, had flown thirty-six missions in that time. He later wrote,

The end of my tour of operations released the tension on the spring which I had kept more tightly wound up than I had realized. I suddenly collapsed and was good for nothing but staying in bed for the best part of a week. A medical check-up revealed that I was totally exhausted. From 6 to 16 November we laid on operations on eight nights out of eleven. I had myself flown on five of these nights and been responsible until pilots were safely landed and debriefed on all eight. Apart from the nervous tension — which one did not notice at the time — this routine left us all very short of ordinary sleep.

It was a strange way to fight a war. Apart from the pistol each pilot carried for self-defence, there was no means of combat. Half of every month was

spent completely free from danger in rural Bedfordshire, training agents and visiting home and loved ones while waiting for the next moon period. The other half, by contrast, was a fortnight of intense anticipation by day followed by a night of either high adventure or frustrating anti-climax when bad weather intervened.

Life on the ground at Tangmere was spent mainly at what was known as ‘The Cottage’. Standing opposite the main gates of the RAF station behind a tall hedge, it was a seventeenth-century dwelling which had been extended considerably over the years. Apart from its kitchen where the establishment’s two flight sergeant security minders doubled as cooks, preparing mixed grills and sumptuous breakfasts for returning pilots and agents, there were two other rooms downstairs. One was for dining and the other was the operations and crew room. In it was a large map of France with the areas defended by flak marked in red. As well as a table and a map chest, an assortment of armchairs was arranged around the coal fire. The only real clue to the clandestine role of the cottage’s inhabitants was a green ‘scrambler’ phone positioned next to the standard black one.

Upstairs, there were some six bedrooms, all with as many beds as there was space for. It was not only the pilots these had to accommodate before and after operations, but SOE agents and all other passengers except those chaperoned by the SIS, who were lodged at Bignor Manor. There was generally a happy, casual atmosphere about the place and, when operations were cancelled, impromptu parties involving the Lysander ground crew members and anyone else in the know were often arranged.

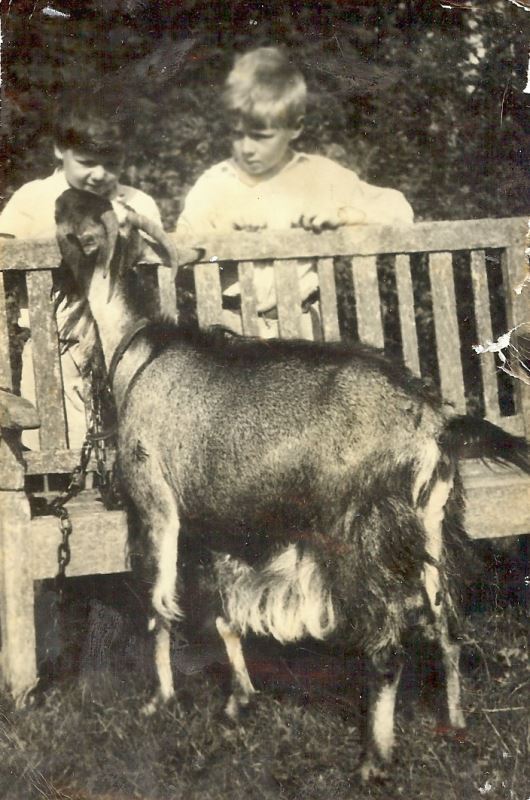

The exuberance of these young pilots, most in their early twenties, occasionally bubbled over beyond the confines of the cottage. They would sometimes take their planes up on days of cancelled operations and swoop low over Bignor Manor, terrifying both Barbara Bertram and her goat, Caroline. At one stage, an order appeared in the flight headquarters forbidding any low flying over Bignor until Caroline was delivered of the kid she was expecting. Caroline, a celebrity among both agents and pilots, was later immortalized when her name was used for one of the pick-up operations. All week prior to the operation, the BBC had solemnly announced news of Caroline: ‘Caroline has a new hat’. ‘Caroline is well’. ‘Caroline went for a walk’. Finally there came: ‘Caroline has a blue dress’ — blue being the associated word telling the French landing party that the mission was on for that night.

Nicky and Tim Bertram with Caroline the goat. (The Bertram Family

)

The pilots who flew the Lysander missions later in the war owed much to two of the pioneers of special duties pick-ups, John (Whippy) Nesbitt-Dufort DSO, Croix de Guerre, and Alan (Sticky) Murphy, DSO, DFC, Croix de Guerre. These two skilful aviators and impressive individuals were anything but the run-of-the-mill caricatures of wartime RAF pilot officers suggested by their schoolboy nicknames and moustachioed looks. Both brought back valuable lessons to the squadron after narrow escapes on enemy soil and one ultimately owed his deliverance from a Gestapo manhunt to the other.

John Nesbitt-Dufort, born in 1912, was brought up in the Home Counties by his grandmother and uncles and aunts after his French father was killed on the Western Front in 1914 and his English mother died a few years later. Passionate about aeroplanes and engines from a very early age, he was accepted as an RAF trainee pilot officer at the earliest permissible age of 17½. Showing above-average aptitude on gaining his wings, he spent his short commission with a fighter squadron, then as an instructor. When war broke out, he had left the RAF and was working with de Havilland, teaching young men destined for military duty to fly Tiger Moths. He soon joined up again and, after a spell of training bomber pilots, then piloting a night-fighter, he was recruited for special duties with 138 Squadron.

He flew five missions during his tour of duty with them between September 1941 and March 1942. The first, the nearly disastrous encounter with a French power cable, convinced his superiors to step up the training for agents in charge of pick-ups in the selection of appropriate landing sites. The second, to a field west of Soissons, near Reims, went without a serious hitch, while the third, to around the same region of France, had to be abandoned when mist obscured the agents’ landing lights. Nesbitt-Dufort returned the following night, however, and brought home one of the SIS’s star Polish agents, Roman Garby-Czerniawski, who was head of the Paris-based network Interallié

. The weather, especially in winter, presented as much danger to the Lysander operations as any German fire power and, when Nesbitt-Dufort set off on his fifth mission in January 1942, it all but got the better of him and his passengers.

Apart from some mercifully inaccurate flak over the French coast, the outward journey and landing in a field near Issoudun went according to plan thanks to clear moonlight over central France. Roger Mitchell, a French agent recruited by Passy to organize pick-ups in France and now on his way back to England with important courier, had done his job of field selection

well. In a matter of minutes, he and his companion, Maurice Duclos, alias Saint-Jacques, were crammed into the Lysander’s rear cockpit and watching the dark French countryside shrinking beneath them. Duclos, Passy’s very first agent, had been on the run in France since the previous August when his Paris-based network had been betrayed by the Luxemburg double agent, André Folmer. Although he had narrowly avoided capture, many of his network were caught and eventually shot while his doting older sister and her niece, with whom he lived, were tortured by the Gestapo and sent to a concentration camp. Duclos had lost all the geniality of the man volunteering for the Free French just eighteen months previously and, as Nesbitt-Dufort was shortly to observe, now ‘displayed a hardness that would have made high-tensile tungsten steel appear like putty.’

The flight back over France at about 7,000 feet was uneventful until, eighty miles south of the French coast, the air started to become turbulent. ‘Suddenly I saw it.’ John Nesbitt-Dufort recalls in his book, Black

Lysander

:

It must have formed up rapidly along the north French coast during the last three hours. ‘It’ was the most wicked-looking and well-defined active cold front I had ever seen. It extended right across my track to the east and west as far as the eye could see and the top of that boiling mass of cumulonimbus clouds, seething upwards like the heavy smoke of some gigantic oil fire, must have risen to well over 30,000 feet — way above the maximum altitude of the Lizzie. From the base of that horror, which was only about 600 feet above the ground, torrential rain fell, while lightning played continually in its black depths.

Seeing that there was no way round either to the west or to the east, Nesbitt-Dufort first opted to descend to 1,000 feet and attempt to fly under the mass of cloud. He soon realized this was a mistake; in the pitch darkness, the rain was forcing his plane ever lower to the ground and his windscreen was white with ice. He made an about turn and emerged again in the clear air, thoroughly shaken up. His next attempt was to fly through the middle of the cloud at about 10,000 feet, relying entirely on his instruments to see him through. Almost immediately, the Lysander began to be tossed around, as he put it, ‘like a leaf in a whirlwind’. Blinded by the continual lightning, his compass unreliable from the amount of static and his air speed indicator iced up and useless, Nesbitt-Dufort fought on at his controls using all the power he could squeeze out of the engine. But the aircraft was losing height.

Opening the cockpit window, he thrust his gloved hand into the slipstream and when he brought it back found it petrified in a clear coating of ice. The same would be happening on all the exterior surfaces of the Lysander, the wings unable to provide the lift needed for the extra weight.

Then the engine, its carburettor choking with ice, began to splutter and, down to 7,000 feet, the aircraft was tumbling, virtually out of control. Nesbitt-Dufort got on the intercom to his two passengers — whom he had tried unsuccessfully to rouse earlier in the flight — and told them, in no uncertain terms, that they should prepare to bail out. There was no reply from them and he soon realized to his horror that they had failed to don their helmets for the flight so were unable to receive the command. They had, in fact, also failed to fit their parachutes but with no visual communication between a Lysander pilot and his passengers, Nesbitt-Dufort would not have known this. All he did know was that if his ‘Joes’ were sitting tight, he would have to do the same. At 5,000 feet, he pointed the nose downwards in an attempt to gain speed to have enough control to turn the plane through 180 degrees in a desperate attempt to retreat from the storm. At any moment, he expected the wings to come off in the turbulence but, to his astonished relief, with the altimeter reading 900 feet, he broke cloud. The engine,

although still extremely weak at first, picked up enough for him to fly on for an hour until, very short of fuel, he put down in a field. The field, unfortunately, had an unseen ditch running across it which caught the Lysander’s undercarriage, tipping it onto the propeller and throwing pilot and passengers violently forward. Much later in his life, an x-ray revealed scars from a triple whiplash fracture, but at the time he assumed that he had simply cricked his neck.

Although he knew he must have landed somewhere in central France, Nesbitt-Dufort had no idea where. As for his passengers, they were asking where the car was to take them to London and expressed exasperated disappointment when told where they had fetched up. It took some explaining by their pilot to convince them how fortunate they were to still be breathing. They would later learn just how fortunate; that same night, thirty-six British bombers failed to return from a mission, nearly all their losses due to the effect of icing in the storm.

John Nesbitt-Dufort’s abandoned Lysander is inspected by officials after he was forced to land in central France after encountering nearly fatal weather conditions on a return trip to England with two agents aboard in January 1942. The plane hit a ditch on landing but the pilot and passengers escaped capture and made it back to Britain a few weeks later. (The Bertram Family

)

Orders were to destroy an abandoned plane in France but, despite three attempts, it would not catch fire, mainly because all the fuel had been used up. The next priority was to put distance between them and the Lysander and discover where they were. They made off across muddy fields and through undergrowth in the darkness and freezing rain which had now reached them, until they came upon a road and a signpost on which they could just make out the words St Florent. The three men crouched in a hedge while Nesbitt-Dufort pulled his RAF-issue survival kit from his hip pocket. Amongst its contents of Benzedrine, a compass, matches, a water purifying kit, chocolate and Horlicks tablets, he was looking for a tissue-paper map of France. By the light of Mitchell’s torch, he fumbled with its folds until, spread out before them, they found themselves peering at a detailed map of Germany. There was also some German currency enclosed. After a moment’s silence, Mitchell and Nesbitt-Dufort could only laugh at this administrative howler. Duclos, however, was far from amused and eyed the Englishman with profound suspicion.

However, Duclos believed he now knew roughly where they were, about a twenty-mile walk from Issoudun, the town close to which they had taken off several hours earlier. They continued their long cross-country trudge towards the town until, still five miles from their destination, Nesbitt-Dufort, close to collapse following his seven-hour ordeal at the controls of the Lysander, insisted on getting some sleep in an empty shepherd’s shed. While Mitchell

kept watch, Duclos went on to find help. At Issoudun, he had brazenly walked into the station bar and shaken hands with everyone present, using the secret cagoulard

means of identification. A number of the railwaymen there were Freemasons and, mistaking his sign as a Masonic one, immediately offered to help him. Duclos returned to the shepherd’s hut with a man and his motor car and three sets of railway track workers’ overalls as disguises. The fugitives were deposited at a level crossing on the outskirts of Issoudun and shambled, in character, along the track towards the station. It had been the station master, M. Combeau, who had organized their cover and it was into his small trackside house into which they now disappeared where, for the next five weeks, the three men would be kept in hiding.

The station master, his wife and fourteen-year-old daughter shared their house and meagre rations with extraordinary hospitality and goodwill, considering the risk they were running. They received news that the Gestapo had arrested the newly arrived priest at the village close to where the Lysander had crash-landed, believing that he was actually the English pilot in disguise. Nesbitt-Dufort, who could not follow the French conversation of his fellow fugitives and their hosts, was not told of this development until news came that the curé

had convinced his captors of his innocence. They had been concerned that their English friend would have given himself up to save the priest and exposed them all under torture. The release of the priest meant a renewed effort to find the real pilot and passengers and the station master’s house was thoroughly searched with the fortunate exception of a tiny basement where the three men hid behind some plate-layers’ tools. German hackles must have been further raised when the man they hired to salvage the abandoned Lysander contrived to get its tail wheel caught in the tracks as it was hauled across a level crossing, suspiciously close to the pulverizing arrival of an express train.

While Duclos and Mitchell had identification papers and could therefore venture out into the town, Nesbitt-Dufort could never leave the house until, with typical nerve and resourcefulness, Duclos succeeded in stealing a blank carte

d’identité

from the town hall and, by cutting a stamp from a rubber heel, supplied instant fake French citizenship to the Englishman. Meanwhile, Mitchell had taken the considerable risk of a trip to Paris where he hoped, via his Franco-Polish network, to make radio contact with London to let them know that they were still alive and that they needed a plane out. He returned several days later with the news that the RAF would make the unprecedented move of sending a twin-engine plane, powerful enough to

carry the three men plus a Polish General, also on the run, who would join them on the night they were due to go.

A disused airfield close to Issoudun had been identified by Mitchell, photographed by RAF air reconnaissance and okayed by 619 Squadron as suitable for a night landing by an Avro Anson. Finally, on the evening of 1 March, the eagerly anticipated coded BBC message came through and the four men made the arduous journey on foot to the airfield. Nesbitt-Dufort was very concerned, when they got there, that the grass field was barely firm enough to take the weight of this 3½ ton aircraft. The plane eventually came in at 12.30 a.m. and made a good landing but, with all men and luggage on board, the wheels stuck in the mud when the pilot opened the throttles for take-off. Nesbitt-Dufort knew what to do, however, and shouted to his fellow passengers to copy him and bounce up and down. The ploy worked and the Anson began to roll forward and then accelerate.

Once in the air, Nesbitt-Dufort went forward to find out which pilot had pioneered this daring landing in such an unconventional aircraft and was delighted to find his close colleague Sticky Murphy at the controls. He was greeted with the words: ‘John, you old bastard! You stink like the Paris Metro. Get the ruddy undercart up, will you?’

On hearing that Nesbitt-Dufort had survived the dreaded report of ‘missing, believed killed on operations’, Murphy had volunteered to fly the mission. The flight touched down at Tangmere three hours later without further incident, blazing a trail of encouragement for the later twin-engine pick-ups using Hudsons. Four very happy and relieved passengers disembarked from the plane and were quickly immersed in the customary celebratory hospitality at the cottage.

They could have been forgiven for not thinking of it at the time, but they would later ruefully reflect that, contained in the courier that they would have delivered five weeks earlier without their mishap, was intelligence that the battle cruisers Scharnhorst

and Gneisenau

were about to leave Brest for a dash up the Channel. By the time the packages were finally opened and deciphered, the two ships, between 11 and 13 February, had already famously slipped through the Royal Navy’s hands and were moored safely in German waters.

After his safe return to Tangmere, the authorities decided that John Nesbitt-Dufort should be moved from special duties flying. This was no reflection

of his conduct, for which he had already been awarded the Distinguished Service Order, but because they felt that he knew too much about both the SIS and SOE circuits and their agents’ identities in France to risk his capture and torture if things went wrong again over France. The mantle of most experienced pick-up pilot was therefore passed to his friend and saviour, Squadron Leader ‘Sticky’ Murphy.

Murphy, from all accounts, was a cheerful, athletic extrovert whose limpid drawl reminded his fellow officers of the film actor, Leslie Howard. His very first Lysander mission, on the night of 8 December 1941, could easily have been his last. He was to pick up an SOE agent from a disused airfield near the southern Belgian town of Neufchâteau but, when he arrived over the airfield, the familiar ‘L’ of lights was visible but the signal being flashed was not the agreed Morse code letter. Wanting to believe that the agent had simply made a mistake or was even in some kind of distress, Murphy decided to go ahead with the landing. Seconds before touching down, his landing light showed a deep depression in the ground ahead so he opened the throttle and flew round again. This time he chose to land a considerable distance from the flare path and sat waiting with his engine running and his pistol at the ready.

Suddenly out of the darkness came what seemed to be an explosion accompanied by a series of bright flashes. He was being fired at by an advancing company of German soldiers. Instinctively, he thrust the throttle lever forward and the Lysander, apparently in working order, was airborne again after a run-up of less than forty yards. Murphy had been hit by a bullet in the neck and, after he had gained some height and set a course for Tangmere, he pulled out a silk stocking which belonged to his wife and which he always carried as a talisman and wound it round his neck to reduce the bleeding. By the time he could call the tower at Tangmere, his voice had become drowsy from loss of blood. His course had also become erratic but thanks to the control tower’s arduous efforts to keep him awake by reciting the most obscene limericks they could remember, he made it home. The Lysander was found to be peppered with some thirty bullet holes.

Back in Belgium, the agent Captain Jean Cassart was also nursing a bullet wound in the arm. He, his radio operator and another helper had been surprised by the German soldiers just as they were about to switch on the flare path lights. All three had managed to escape into the darkness amid a volley of German bullets. Cassart, hidden beneath the wall of Neufchâteau

cemetery, willed the Lysander pilot not to land as he watched the Germans light the three torches.

In spite of his eventual capture and incarceration in Germany, Cassart made a miraculous escape while being tried in a Berlin courtroom and eventually made it back to England and survived the war. Sticky Murphy was sadly not so fortunate. He recovered from his neck wound and went on to fly five more wholly successful special duties missions. These included one that airlifted Gilbert Renault from a snow-covered field near St Saëns, between Dieppe and Rouen in the occupied zone, and the Anson pick-up of the following March. He was posted elsewhere in June 1942 and, having reached the rank of wing commander at the age of 27, his luck finally failed him when piloting a Mosquito on bomber support in December 1944. His plane was hit by flak over the Netherlands and crashed near Zwolle, killing himself and his navigator.

Guy Lockhart, having risen meteorically from the rank of flight sergeant to that of squadron leader in less than three years, succeeded Sticky Murphy as commander of the Lysander special duties flight in June 1942. By then, he had already completed four pick-up missions from Tangmere (including the successful Operation Baccarat II described in Chapter 1), and had previously served with distinction as a Spitfire pilot. He had had more than the fleeting acquaintance with occupied France enjoyed by most Lysander pilots, having been shot down in his Spitfire the previous July, some twenty miles inland from Boulogne. Like Nesbitt-Dufort, he experienced the hospitality and bravery of those working under cover for the allied cause, being spirited first to Marseilles in the free zone, then on to the Pyrenean border where he was led across the mountains into Spain with a party of other fugitive British airmen. Lockhart was arrested in Spain and spent some weeks in the nationalist concentration camp at Miranda del Ebro before his release and repatriation in October 1941.

As flight commander, Lockhart continued to do his share of the work, successfully navigating his Lysander to an old airfield in the Auvergne, east of the town of Ussel and close to the limit of the aircraft’s range. Here, he collected Léon Faye of Fourcade’s Alliance

network. A few days later, on 31 August 1942, he set off again, this time for a field among the vineyards of Burgundy. Christian Pineau’s story, later in this book, will reveal the near disastrous touchdown.

By this time, 161 Squadron had six Lysanders at its disposal, plus one in reserve, to meet the increasing demand for pick-ups in France. The web of

intelligence agents and resistance cells was continually growing along with the need to ferry key individuals in and out of Britain for high-level briefings, for training or simply to provide sanctuary from the Gestapo. Whereas in the early days there may have been one or two operations during every moon period, by the end of 1942, this had increased to as many as twenty if the weather was favourable. A string of individuals of appropriate skill and character were now drafted in to fly the missions.

They ranged widely in age and experience. The tall, laconic, jazz-loving 19-year-old Peter Vaughan-Fowler had applied and been selected after the signal asking for volunteers had omitted the word ‘night’ in its intended specification of ‘at least 250 hours of night flying experience’. He had less than 250 hours in total under his belt but proved to be a very fast learner, completing twenty-six missions without mishap before his eventual re-deployment as a Mosquito pilot.

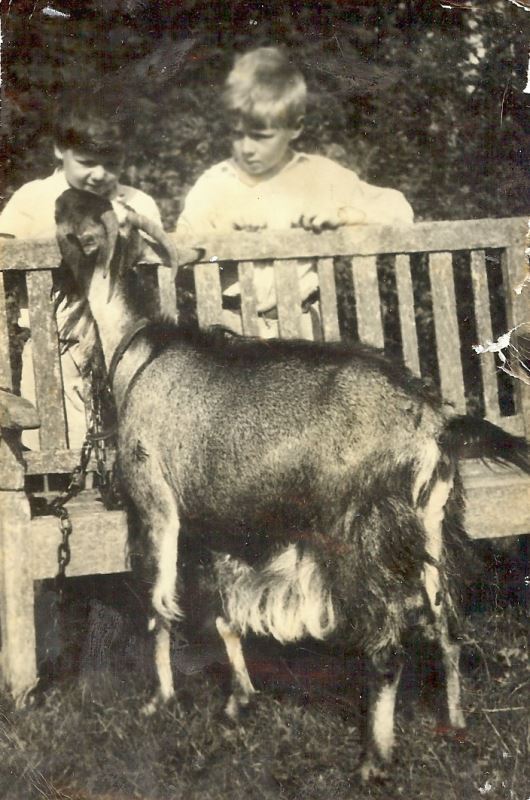

Pilots of 161 Squadron in summer 1943, (l to r), Robin Hooper, Jimmy McCairns, Peter Vaughan-Fowler, Hugh Verity, Frank (Bunny) Rymills and Stephen Hankey. (The Bertram Family

)

On the other hand, John Bridger, older than the other pilots and a man of few words, was a highly seasoned recruit with 4,000 hours of flying already behind him. He, too, ended his time with the squadron unscathed after a dozen sorties, although only his handling skill saved him on one occasion in April 1943. His Lysander overran the plateau designated for his landing south of Clermont-Ferrand and, in his desperate attempt to become airborne again, he hit the crest of the ridge beyond, destroying one of the tyres of his undercarriage and flying through high tension cables between two pylons. Recovering his vision from the blinding flash this had caused, he brought his plane round again and made a successful landing. In order to take off from the field on an even keel, he punctured his one good tyre with several shots from his pistol. His eventual landing back at Tangmere was uneventful in spite of the punctured tyres, except that seven metres of thick copper wire could be seen trailing behind him as he touched down on the tarmac.

Frank ‘Bunny’ Rymills, a veteran of twenty-six bombing raids and twenty-four clandestine parachute drops, was still only 21 when he joined the Lysander flight. On the ground, he was inseparable from his cocker spaniel, Henry. A former student of architecture and an avid beekeeper, Rymills was also a skilled poacher, the mentality for which must have suited the nocturnal stealth and daring required of a Lysander pick-up pilot. He only spent six months with the squadron, but still carried out twelve operations, ferrying some thirty agents in or out of France.

On one occasion, in June 1943, Rymills forgot to switch off his radio transmitter while communicating with his two female passengers, Cecily Lefort and Noor Inayat Khan, as they flew over the French coast on their way to a landing site near Angers. Possibly to calm their nerves, he was pointing out how beautiful it looked in the summer moonlight and identifying towns and other landmarks to them. This was a double Lysander operation and it was with considerable horror that James McCairns, his fellow pilot, endured more than thirty minutes of this running commentary over his headphones, knowing that the Germans would be listening to every word. Rymills’ indiscretion would not affect the safe completion of the mission, and all four outward bound agents (McCairns was carrying Charles Skepper and Diana Rowden) were successfully spirited away to take up the various assignments they had been given by the Special Operations Executive. Tragically, not one of this quartet would make it back to Britain. All were eventually caught and tortured by the Gestapo; Cecily Lefort never returned from Ravensbrück concentration camp, Noor

Inayat Khan was executed at Dachau, Diana Rowden at Natzweiler and Charles Skepper also died in Germany from the injuries inflicted by his captors.

James McCairns, or ‘Mac’ as he was known, had joined the Lysander flight in the autumn of 1942. Still only 23, he had flown a Spitfire as a sergeant-pilot in Douglas Bader’s renowned 616 Squadron. McCairns’ service alongside the legendary pilot that he so greatly admired was cut short in July 1941 when he was shot down, wounded and captured by the Germans. By the following January, he had recovered sufficiently to make a successful escape from his prisoner-of-war camp in Germany and had reached Belgium. Thanks to the Belgian underground and MI9’s escape organization in Europe, McCairns was smuggled to Gibraltar and returned to the UK. During his concealment in Belgium, he had heard about the black Lysander operations and at one point was expecting this to be his way out of occupied Europe. Back in service with the RAF, he became determined to repay those who had helped him escape by volunteering as a pick-up pilot.

As a non-commissioned pilot with limited flying hours due to his incarceration, his application was scrutinized closely by the Tempsford commander, Mouse Fielden. However, the understanding he had gained of how the Resistance worked while he was on the run stood him in good stead and he was taken on. The decision was undoubtedly vindicated as McCairns went on to complete twenty-five successful pick-ups and earned the Distinguished Flying Cross and Military Medal, even though his second operation on 22 November 1942 led to his being temporarily suspended. It was a double Lysander mission with Peter Vaughan-Fowler and, as with all double missions, there was a strict rule that either both planes should land at the target or neither. Furthermore, Vaughan-Fowler, as the senior pilot, should land and take off first.

It was quite a short trip to the east of the Seine, between Rouen and Paris, but there was low cloud and patchy fog over France and the landing site was difficult to locate. The two pilots lost sight of each other as they searched for the agent’s signal and radio contact was fitful. McCairns mistakenly thought that Vaughan-Fowler’s brief and indistinct message that he was setting course for home meant that he had landed successfully and exchanged his passengers. Therefore, when he spotted the correct signal, he brought his plane down and was disconcerted to hear from the reception party that the other Lysander had never put down. Five people were waiting on the ground for their flight to England and the decision was taken to cram four of them into the Lysander cockpit — the first time such a number had been carried. Amid

all the recriminations McCairns encountered on his return to Tangmere for having unintentionally disobeyed orders, he was able to take some comfort in the fact that the four he had rescued were Max Petit, an important operator in Gilbert Renault’s network whose cover had just been blown, his wife and their two young sons. In fact, although he did not know it at the time, the Gestapo arrived to arrest the family only one day after their airlift to safety.

The man responsible for disciplining McCairns was the newly appointed commander of 619 Squadron, Wing Commander Percy Pickard. ‘Pick’, as he was universally known, was 27 and already a highly distinguished figure in the RAF and seemed a good ten years older to his contemporaries. He had earned the DFC, the DSO and a bar flying bombers and had led the famous parachute raid on the German radar station at Bruneval on the French coast near Le Havre in February 1942 (about which more will be told in Gilbert Renault’s story in the next chapter). He went on to become the first RAF officer to win a second bar to the DSO in 1943 as a result of his work as a Lysander and Hudson special duties pilot. Pickard’s face was also well known outside the RAF because he had appeared as the pilot of ‘F’ for Freddie, a Wellington bomber featured in an Oscar-winning 1941 documentary, Target

for

Tonight

. He was a tall, heavily-built man with very fair hair and a pointed nose. He was seldom seen out of his cockpit without his pipe and his Old English sheepdog, Ming.

He clearly also believed in taking some home comforts with him on operations. In January 1943, he was returning from a field near Issoudun with the former French ambassador to Turkey, René Massigli, and André Manuel, Passy’s right-hand-man in the Free French intelligence service, on board. To his great concern, he could not recognize where he was as he crossed the French coastline. Trusting his compass, he carried on across the Channel but as his fuel gauge continued to fall, there was no sign of land ahead. At last, with the needle on empty, a rugged coastline appeared: it was the southernmost tip of Cornwall. Fortunately, there was fortunately an RAF airfield at Predannack, near Lizard Point, and he made it down without a drop of fuel left in the reserve tank. It transpired that the Lysander’s compass had been affected by a metallic object in one of Pickard’s flying boots. It might have been the bayonet he carried there or it could have been the stainless steel whisky flask he had shoved into the top of his boot after a fortifying swig.

As well as doing his fair share of Lysander pick-ups, Pickard was the man to demonstrate the suitability of the larger Hudson for moonlit landings in France. He developed the technique of bringing the aircraft in to land at

a speed much slower than the 75 knots recommended in the pilot’s handbook and needing only 350 yards to pull up on landing. He then flew 619 Squadron’s first successful Hudson mission in February 1943, bringing seven agents back from a field south-east of Arles in the Midi. It was only a year later when, as the leader of a Mosquito squadron, he was part of the daring Operation Jericho, a bombing raid on Amiens prison to free resistance fighters condemned to death by the Gestapo. Although the raid succeeded, Pickard was caught from behind by a German fighter plane as he left the scene, his tail was severed and he and his navigator died as the plane turned turtle and crashed to the ground. He left a wife, Dorothy, and a one-year-old son.

Pickard’s new Mosquito command and the posting of Peter Vaughan-Fowler to fly in the same squadron, together with other impending departures, meant that replacements were required for Lysander special duties in the later months of 1943. They came in the shape of four men, Jim McBride, Robin Hooper, Jimmy Bathgate and Stephen Hankey. Jim McBride, a tall, muscular but shy man was a product of Strathallan School in Scotland and St Catherine’s College, Cambridge, who left university to join the RAF in 1940. His flying experience had been with Wellington bombers over much of Europe. Robin Hooper, an Oxford graduate, who had learnt to fly with the university air squadron, had entered the Foreign Office before the war but had persuaded his masters to let him pursue active service with the RAF when hostilities began. He had already been carrying out special duties with 138 Squadron, parachuting agents and supplies as a Halifax pilot.

Jimmy Bathgate was a small, fair-haired New Zealander, an accomplished pilot and a scrupulously careful navigator. In ten missions between September and December 1943, he carried twenty-seven passengers in and out of France. On the night of 10 December, he set out from Tangmere on a double Lysander operation with Capitaine Claudius Four on board, an important co-ordinator of the Resistance in central France. Jim McBride was flying the other aircraft and their target was a field near Laon, to the north of Reims. The weather was very poor and it was no surprise to the ground crew at Tangmere when McBride reported a failed mission on his return. To their mounting concern and ultimate dismay, there was no second Lysander home that night. No one knew what had happened and it was only six months later that news came out of France that Bathgate’s plane had been shot down near a German night-fighter base at Juvincourt on the Laon to

Reims road. Both he and his outward bound passenger had been killed.

It was after sombre events such as Bathgate’s failure to get home that pilots of the squadron looked to the most flamboyant of their number, Stephen Hankey, to lift them from their gloom. If his patrician demeanour gave the brief impression of a Bertie Wooster, it was soon dispelled by his sharp and outrageous wit and a resourcefulness which would not allow the strictures of his and his fellow pilots’ military life get in the way of their well-being. ‘Any bloody fool can be uncomfortable’, he would say as he organized, against all regulations, to install his wife and two young daughters in a cottage close to Tangmere. He had made a similar arrangement at the beginning of the war, finding a flat in Paris for his wife so that he could make frequent visits from his posting with one of the army co-operation Lysander squadrons which took such a battering over northern France prior to Dunkirk.

Hankey felt very much at home at Tangmere, having been brought up as the youngest son of a distinguished Sussex family in a large country house, Binderton, on the other side of Chichester from the aerodrome. Barbara Bertram, a long-standing friend of the family and nine years Stephen’s senior, had watched him growing up and was delighted to welcome him, along with the other Lysander pilots, to her impromptu parties at Bignor Manor. The Hankey family had, in fact, vacated Binderton House during the war and loaned it to their friends Anthony Eden and his wife Beatrice, who used it as a retreat from the exigencies of a wartime Foreign Office. On one occasion, Hankey invited the Edens over to tea at the Cottage in Tangmere. After he had given him a guided tour of their establishment and introduced the pilots, Eden confessed that he had no idea that ‘all this’ was going on. As he was Foreign Secretary, everyone roared with laughter.

Hankey’s flying career had only begun after a short spell in the army which had marked him with a broken nose sustained while boxing at Sandhurst and which sometimes gave him agonizing sinus pain when at the controls of a plane. After trying his hand as a salesman of Delahaye sports cars in London, he joined the RAF and, following his traumatic tour of duty in France, was sent to the Middle East to train allied aircrew cadets. Each button on his RAF tunic was from a different air force as a memento of this work. At 28, he came to 619 Squadron older than most newcomers and with very little night flying experience. He trained hard, however, to come up to the standard of his fellow pilots and flew his first mission, a successful pick-up to the west of Paris, on September 14, 1943

.

The man whose memoirs we have to thank for so much of this information about the Lysander moonlight flight is Hugh Verity who, having qualified as one of its pilots in November 1942, simultaneously became its commanding officer at the tender age of 24. The son of an Anglican clergyman, educated at Cheltenham and Queen’s College, Oxford, where he read French and Spanish and learned to fly with the university air squadron, he joined the RAF when war was declared in 1939. By the time he volunteered for the special duties squadron, he had flown bombers with coastal command and spent a year as a night-fighter pilot. These postings had not been enough to convince him he had yet quelled the demons of physical cowardice that had beset him on the rugby fields of Cheltenham and he was determined to prove his courage in the lonely night skies over enemy territory.

Although his book, We

Landed

by

Moonlight

, never makes it obvious, it is easy to deduce that this calm, courteous and competent airman commanded great respect from the unconventional group of pilots for whom he was responsible. He flew more missions than any of them during his time in charge and made as many life-long admirers among the French Resistance men and women as he did among his RAF peers. His book makes it very clear how important the bond was between the Lysander and Hudson pilots and the agents responsible for their reception on French soil. The chances were that the pilot and agent in charge of a landing would know each other well because they had trained together in England. Warm greetings took place up at the pilot’s cockpit in the brief minutes of a passenger exchange and generous black market gifts of wine and perfume were thrust into the pilot’s hand.

Hugh Verity had established a particularly strong relationship with one of the SOE’s most trusted and frequently called-upon agents, Henri Déricourt. Déricourt, himself a skilled aviator, had come to Britain in 1942 via Spain and Gibraltar thanks to the MI9 escape network and hoped to secure a job flying for BOAC. The MI5 vetting process for newly arrived foreigners channelled him towards the SOE, however, who took him on in spite of a somewhat equivocal report on his credentials. The Frenchman clearly had great charm and easily convinced Maurice Buckmaster, head of the SOE’s F Section, to give him responsibility for organizing their agents’ arrivals and departures in France. Déricourt’s beguiling nature was such that Hugh Verity was moved to write to his wife at the end of their pick-up training together to say, ‘I have a very good friend called Henri. I have given

him your telephone number and told him that you would do whatever you could to help him, no matter when. Don’t forget, Darling, even if he rings up after several years, to think of him as an old friend of mine. You will find him very nice.’

It is now widely believed that Déricourt was a traitor. His trial in Paris in 1948 failed to convict him and this was partly because his SOE masters seemed so reluctant either to believe in or admit to his duplicity. None of them gave evidence against him and one, Nicholas Bodington, appeared in his defence. German records have nevertheless shown him to be in the pay of the Sicherheitsdienst

, the SS security service, and one of its officers had borne witness to his dealings with them. An even darker theory that Déricourt was a triple agent, secretly working for the SIS who were happy to sacrifice agents of the SOE to the Gestapo as they had been fed false information about where and when the allied invasion was planned, has yet to be convincingly proved.

The sense of betrayal must have been doubly bitter for Hugh Verity; not only because of his fondness for the man but also because he discovered that, on each of the eighteen occasions that Déricourt had led the reception committee for Lysander pick-ups, he and the other pilots had been delivering brave men and women to their near-certain capture, torture and death. The lucrative deal that Déricourt struck with the Germans meant that, while the planes were allowed to land and take off unscathed, he would supply details of every incoming and outgoing flight and individual on board. (The quartet flown out by Rymills and McCairns in June 1943 were probably victims of his treachery). He also made copies of all the messages due to be flown back to London and passed them on to the Germans.

The safe passage granted the unwitting Lysander pilots on some of their flights made them no less courageous. They understood very well the kind of fate that might await them if they were caught on enemy soil, especially as the war lengthened and stories got back about the Gestapo’s methods of extracting information. It was only by sheer good fortune and by the bravery of those who sheltered them that every pick-up pilot stranded in France evaded capture and eventually made it home. By the end of the Lysander special duties into France in 1944, five more pilots besides Jimmy Bathgate would lose their lives, however — victims either of bad weather or enemy fire. Compared with other RAF wartime operations, the ratio of such losses to successful missions was remarkably favourable and testament to the skill and daring of the men who flew them.