CHAPTER 6: THE BIRTH OF AN INTELLIGENCE NETWORK

Gilbert Renault’s Story — Part 1

Barbara Bertram might have found it difficult to believe that the determined and highly prized agent of the Free French and British intelligence services, who had bid her a tense farewell on the doorstep of Bignor Manor in the early spring of 1942, was the same man who, twenty-one months earlier, had found himself so paralysed by indecision at his home in Vannes, Brittany.

Gilbert Renault, alias Rémy, creator of the intelligence network, Confrérie de Notre-Dame

. (Musée de l’Ordre de la Libération

)

Gilbert Renault had faced an excruciating dilemma as the German army forced its way westward towards its coveted prize of the French Atlantic coast in the days leading up to Pétain’s armistice of 22 June 1940. Every ship of the French Navy had been ordered to leave their west coast home port before the invaders reached them and sail either to British or North African waters. Renault had heard rumours that they were taking on board able-bodied civilians prepared to offer themselves for the fight against Germany and the squadron based at nearby Lorient was due to set sail at any moment.

At the outbreak of war the year before, Renault had immediately volunteered for the army but his age had counted against him and he had remained a civilian, pursuing his career as a film producer, having previously worked for a bank and an insurance company. He was a devout catholic and an ardent nationalist, subscribing to Action

Française

, an extremely right-wing daily newspaper that advocated the return of the monarchy and the reinstatement of Roman Catholicism as the state religion. Now, his sense of

outrage at France’s humiliation kindled a fierce desire to flee the French mainland and help perpetuate the fight from an unoccupied shore.

But to do so, this quintessential family man would be abandoning a pregnant wife and four young children to an unknown fate at the hands of the Nazi occupiers. They were not his only responsibility; he was the oldest of nine children and his widowed mother and five of his sisters (the sixth

was married and living in England) would be left without his protection. Of his two brothers, one was serving locally as a marine and the younger, Claude, who was not yet twenty, had resolved to accompany Gilbert should he decide to make an escape.

It was his wife, Edith, who, in spite of her tears, helped Renault to make up his mind by telling him he should go. With two young friends of Claude, also keen to carry on the fight from abroad, the four men set off westward to Lorient in an ancient and temperamental Citroën. German tanks had already reached the outskirts of Vannes, but the Frenchmen’s local knowledge allowed them to circumnavigate the blockade and eventually reach the harbour at Lorient, which was shrouded in black smoke after the fuel depots had been set ablaze by German bombers.

But the Navy squadron had already sailed and it was only by chance that they came upon a trawler, La

Barbue

, which was being loaded with 500 million francs’ worth of bank notes and ledgers, salvaged by the Banque de France ahead of the advancing Germans and destined for Casablanca. The trawler was to provide the first leg of the shipment as far as Le Verdon at the mouth of the Gironde estuary. A sympathetic naval officer they had met on the quay helped them persuade the trawler’s skipper to take the four men with him. There would be a better chance at Le Verdon for them to find a ship bound for England or North Africa.

Although their slow journey down the west coast of France was without incident, they were fortunate. Only a few hours after they had sailed, another trawler, La

Tanche

, weighed down with a crowd of young naval trainees, had attempted to leave Lorient. Twenty minutes out of the harbour she struck a mine, recently laid by the Luftwaffe, and quickly sank. There were only twelve survivors. On the quay at Le Verdon, Renault and his companions witnessed the hasty embarkation of a number of French politicians fleeing to Morocco as well as the British Ambassador and his wife boarding the captain’s barge of a Royal Navy ship, waiting in the estuary to take him home. They were still just one step ahead of the German ground troops although they only narrowly escaped a salvo of bombs dropped on the harbour by the Luftwaffe.

By pure chance, the four men, despairing of finding anyone willing to help them gain a passage to England in spite of the hundreds of ships moored in the mouth of the Gironde, came upon a man digging the flowerbed in his garden as they wandered aimlessly through the small town. He turned out to be the captain of the port, Henri Guégant, and became

determined to help the quartet make their escape. He had been inspired by General Charles de Gaulle’s first BBC broadcast from London two nights previously, on 18 June, and with sadness showed Renault his local paper which had reproduced a vehement disavowal of the general’s words by the French government from their temporary Bordeaux headquarters.

Through the offices of the port captain, the skipper of a Norwegian freighter, the Lista

, was found to be willing to take Renault and the others aboard his ship. That same evening, the fugitives were heading north-west, bound for Falmouth and on a route that would take Renault back past the Gulf of Morbihan, painfully near yet so far from the family he had left only a few days earlier.

At Falmouth, Renault and his companions were corralled with hundreds of other newly arrived refugees from France in a theatre building with scarcely enough space to sit on the floor. While they were waiting to be interviewed by immigration officials, someone passed them a copy of the Sunday

Times

which carried the shocking news that Pétain had accepted Hitler’s armistice terms. Another semi-prison awaited the four men in London where they had been sent, having told the officials they wanted to fight. This was a makeshift recruiting centre for foreigners set up at the Camberwell Institute in Peckham and from which they were forbidden to stray. Days went by with no sign of any call-up for them until Renault discovered a telephone booth and made a forbidden call to Kay Harrison, the London director of Technicolor and a man he knew well through his film production work.

Harrison was able to persuade the authorities that the Renault brothers were no threat to security and arranged for them to be put up in a colleague’s house in Gerrards Cross. From there, they were free to pay a visit to General de Gaulle’s headquarters at St Stephen’s House in Whitehall. This was a day or two after the harrowing news had reached them of the Royal Navy’s 3 July attack on the French fleet in the Algerian harbour of Mers-el-Kebir, in which 1,300 Frenchmen had lost their lives. While the French admiralty had considered their navy still to be an independent fighting force, the British, fearing that its ships would fall into German hands, opened fire when they refused either to hand over or scuttle the fleet.

Both Gilbert and Claude had taken great comfort in de Gaulle’s angry but measured reaction to the news and were all the more determined to swear their allegiance to his cause — and, if at all possible, to the general himself. In the event, they had to content themselves with a meeting with a

recruiting officer, but they were assured that their names were now on the list and the call would come for them in due course.

Waiting for that call was a painful time for Gilbert Renault. He spent long, hot summer days with little to do but lounge on the lawn of his Gerrards Cross hosts and read what he hoped were exaggerated newspaper reports of Nazi brutality in occupied France. Sometimes he would watch clouds drift overhead and imagine the same clouds carried across the Channel to France, soon to pass over his loved ones in Brittany. He began bitterly to regret leaving them to an unknown fate.

A yearning to return home was what led him to pay a second visit to St Stephen’s House and to put an idea to the recruitment officer he had seen a few weeks earlier. His passport contained visas showing that he had been given permission to enter both Spain and Portugal on several recent occasions while making a film about Christopher Columbus. He was sure he could get further permission to enter these two countries again from their UK consulates. Might that not be a means for him to regain French soil and to carry out some kind of secret mission against the occupation?

Renault was immediately referred to the Deuxième

Bureau

, de Gaulle’s intelligence service, and found himself sitting opposite its chief, André Dewavrin, alias Captain Passy. This youthful but prematurely balding man, often nervously biting at his nails, showed little enthusiasm, it seemed to Renault, at his impromptu explanation as to why he was so well served with his business connections throughout France to carry out clandestine work. Passy, who excelled at succinct summations of his first impressions, recalls ‘... a chap of about 35, solidly built with a strong, rounded, slightly balding head. Full of go and dynamism, he spoke in a measured, precise way and showed an almost uncanny sensitivity to nuances.’

During the interview, a man in a lieutenant’s artillery uniform had entered the room and shown a more demonstrative interest than Passy in Renault’s proposition. This was Maurice Duclos, alias Saint Jacques, an early recruit into the Deuxième

Bureau

, who would play an important part in intelligence-gathering in France in the ensuing months and years.

Renault was again summoned to St Stephen’s House where a less reserved Passy told him that he had spoken to his British counterparts who also thought his access via Spain and Portugal was valuable. He was instructed to apply immediately to the two embassies for an entry visa and to await further instructions. He should not set foot again in St Stephen’s House and no one should know about their meetings

.

Meanwhile, Renault’s brother, Claude, had received his military call-up and was already at a training camp. His perplexity as to why his brother’s application was taking so long turned to bitter astonishment when Renault eventually had to tell him that he had had second thoughts about abandoning Edith and the children and would return home via Spain in the next few days. It would be four years before the two brothers saw each other again and Claude could know the truth. If his brother’s disillusionment was hard to bear, it was still less burdensome to Renault than sensing the distress of his wife, who would have no idea where he was or what had become of him. Any attempt to send a letter by post would have risked reprisals against them. However, an idea he had of sending a message via the BBC French service to his wife, containing nothing that could identify sender or recipient, bore spectacular fruit. He was invited by the BBC to their studios to read the letter over the air himself. Although the letter contained personal references which would leave Edith in no doubt who it was from, it also expressed sentiments of defiance against the Pétain/Germany pact and of extreme anguish at abandoning one’s family to the invaders which would be felt by thousands of French exiles in Britain.

Renault knew that he had definitely been accepted into the world of clandestine intelligence when Passy told him to report to the British Secret Intelligence Service with a memorandum outlining the methods by which he intended to gather information about the enemy in France. It soon became very clear to Kenneth Cohen, the Royal Navy officer who received him, that this new recruit knew nothing about working under cover. Renault deduced, however, that it was his honest confession to that effect that convinced his interviewer that he was, at least, trustworthy and that they had better make the most of what they had.

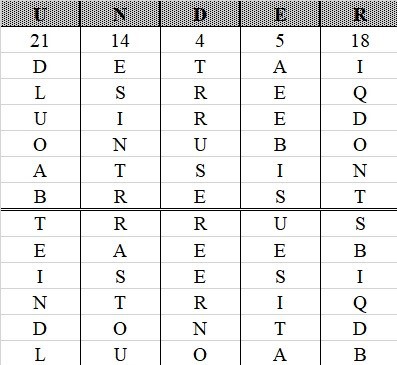

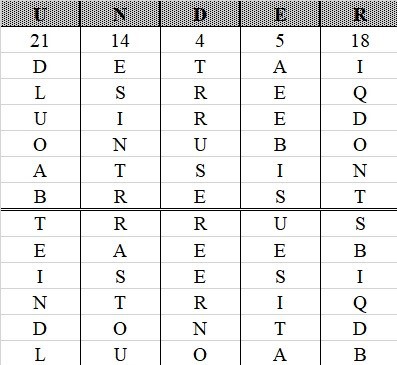

The most crucial practical tool of all in his new role would be to be able to operate the system of encoding and deciphering messages between London and France once he was in the field. Renault’s instruction in this was delivered in one brief session by a large, moustachioed, Scots officer in tartan trousers. The system was based on a random five-letter key that would change each time a message was sent. This was done by selecting a five-letter word from a book, an identical edition of which would be held by both agent and London. The sender would identify the key word by a number made up of the page, paragraph and word number in that paragraph. For instance, the code 161 4 23 would indicate page 161, paragraph 4, word 23

.

Say this gave the key word ‘under’, it would be entered in a grid as shown below. Beneath each letter would be shown a number corresponding to its position in the alphabet. Then the message itself, for instance, details

required

on

U

-boats

in

Brest

, would be entered into the grid. Then a second grid would be filled in by taking the vertical column under the lowest numbered letter, in this instance, D, and writing it horizontally into the grid. Then the next lowest numbered column (E) would follow on as shown below. This provided the jumbled message for transmission. To decode the message, the five-letter key would be used to reverse the sequence.

Learning how to work this code, along with instructions on the use of invisible ink, was the only training Renault was to receive before he was summoned to the Free French headquarters, now at Carlton Gardens. Here, Passy handed him his air ticket to Lisbon, a few dollars for his time in Portugal and Spain and some 20,000 francs for when he arrived in France. He stressed to Renault how he was primarily an agent of Free France and should only follow directives signed by him and that all messages to do with the administration of his network should be sent in a code only decipherable by the Deuxième

Bureau. The fact he gave no indication of precisely how he was to establish an intelligence network

seemed not to concern either man unduly. By chance, Renault encountered General de Gaulle himself on the staircase as he was leaving Passy’s office and introduced himself proudly as one of his soldiers about to leave on a mission to France. The general, after a few brief questions about how he had come to England, shook Renault’s hand and assured him he was counting on him.

Renault left the UK in considerable luxury aboard a Sunderland flying boat, which took off at breakfast time from Poole Harbour and landed him in the Tagus estuary at 5 o’clock in the evening. From there, he made his way to Madrid, a city he knew well and where he had several valuable friends and contacts from his preliminary work the previous winter on the Christopher Columbus film. To some, such as Mme O, a German woman who worked as an embassy official in the Spanish capital but whom he still counted as a great friend, he professed a view that the war would soon be over, with Britain going the same way as France, and explained that he had come to Madrid to continue work on the film. She was able to use her contacts to extend Renault’s permission to stay in Spain from forty-eight hours to a month.

But to an even greater friend, Jacques Pigeonneau, the French consul in Madrid, Renault revealed his real reason for returning to Spain. For his part, Pigeonneau showed Renault secret correspondence he had entered into with de Gaulle, telling him of his intention to resign his position under the Vichy government and put himself at the general’s disposal. De Gaulle had replied that he would be of more value to him if he remained in post. Renault’s arrival on the scene persuaded Pigeonneau to do as de Gaulle suggested and he immediately agreed to receive reports sent by Renault from France and to deliver them to Passy’s letter box in Madrid.

From Madrid, Renault had also been able to get a letter home. His hotel doorman knew an employee of the German embassy who travelled regularly to Paris and who, for 100 pesetas, would post Renault’s letter in occupied France. For the benefit of German eyes, and hoping his wife would read between the lines, he repeated his sentiments about the war being nearly over and told her to bring the children to Madrid while he began work on the film. The letter got through and Edith was even able to send an answer confirming that she would make her way to the Spanish border. Meanwhile, Renault made a trip back to Lisbon, where he delivered messages and blank French passports (taken from the French consulate’s safe and invaluable to Passy) via a British-run letter box. On his flight back

to Madrid, Renault found himself seated next to a senior officer in the Gestapo, whom he entertained with some of the ribald stories about Hitler, Churchill, Mussolini and Goering that had been circulating in France before the invasion. When he landed, the news awaited him that, thanks to his embassy contacts, his family had made it safely to San Sebastian on the north Spanish coast. He was with them the very next day.

Scarcely had Renault installed his family in a Madrid apartment than he received an urgent message from London to return once more to Lisbon. He thought Passy himself had flown out to meet him, but he was confronted instead by an Englishman who identified himself as Major ‘J’ of the British SIS. He told Renault, somewhat boorishly, that he was his boss (at which Renault had to suppress a sharp objection — the French secret service worked in co-operation with the British, not in subordination to them), and gave him a rendezvous for later that day on the ferry across the Tagus.

As the two men strolled in the open air on the opposite bank of the estuary, the Englishman passed Renault a piece of folded paper and told him not to look at it until he was back in his hotel room that evening, where he should memorize its contents and then burn it. Mildly irritated and amused at such typically obsessive British secrecy, Renault nonetheless obeyed the instructions. The note consisted of twenty questions about the German submarine base that was being built in the Bacalan basins at Bordeaux. His first mission in France would be to find the answers to these questions and to find a means of conveying them back to London with the minimum delay. At that time, November 1940, sufficiently portable and user-friendly radio transmitters were thin on the ground, although Renault had been told that the British were working on procuring one for his purposes.

Having been able only to secure a one-way visa from the Spanish authorities to enter France, Renault nonetheless promised his wife that he would be back in Madrid for Christmas. His train journey across the border took him to Pau at the foot of the French Pyrenees where every shop window displayed re-touched photographs of the beloved Marshal Pétain. At his first port of call, Renault was shocked by the attitude of a friend and former colleague, Jean Ribes, whose country house lay near the neighbouring town of Tarbes. He had had no qualms about telling this man of his mission in France, hoping that he would become a key contact, lending Renault facilities at his Paris office as and when they were required. Ribes made it very

clear that he believed Renault’s enterprise to be hopeless, even though he said he could be counted on as a last resort. This defeatism, from a man he knew to be an enterprising, risk-taking businessman, was echoed in all the newspapers Renault found on sale at Tarbes railway station. Their sermonizing tone, implying that France had somehow deserved her defeat and needed now to earn her redemption under the strictures imposed by Pétain and the Germans, depressed and repelled Renault.

Although it was still by no means certain that London would be able to make a radio available, Renault nevertheless set about first in search of an operator in the hope that they would. Passy’s office had given him the name of a café owner in Marseilles, apparently a patriot who could identify an operator. But to Renault’s horror, although the restaurateur said he knew the man who had given his name, he had absolutely no contacts with radio operators and, anyway, would not support such an activity.

Renault made a hasty retreat, wondering how often and to whom the man would repeat the story of his meeting with one of de Gaulle’s undercover agents. He took a train to Grenoble, hoping to find a more sympathetic reception and some leads from Passy’s wife, who lived there in a small apartment with their two children. However, he was concerned to discover when he met her that there were a number of French servicemen in her circle who knew precisely what her husband’s role was in London. Renault told her that inevitable gossip would eventually reach the police and she must prepare to take her leave with her children and that he would arrange for their safe passage across the Spanish border in due course.

Failing to find any potential recruits or radio operators in Grenoble, Renault headed west again to the Dordogne, where London had told him there was a man named Paul Armbruster, sympathetic to the Gaullist cause, who had fled the occupation of his native Alsace and was living close to the demarcation line outside Sainte-Foy-la-Grande. He should be able to help Renault find a way to cross the line undetected for his mission in Bordeaux. Agreeing to join Renault’s embryonic network, Armbruster told him to find his way to the somewhat dilapidated château of La Roque near Saint-Antoine-de-Breuilh, on the river to the west of Sainte-Foy. This was the ancestral home of Louis de la Bardonnie, his wife and eight children. This local wine grower had already established a small local intelligence organization of his own in support of the Free French and had set up a method for crossing into occupied France, the demarcation line running close to his house. He had made his outfit known to London

and was hoping to be sent a radio transmitter and someone to direct their efforts. Renault, arriving panting from the steep climb to the château on his recently acquired bicycle, was, whether he knew it or not, about to fulfil the second of these requirements.

Louis de La Bardonnie’s château La Roque, close to Sainte Foy-la-Grande on the Dordogne where Renault began to build his network and where the first radio link with London was established. (Edward Wake-Walker

)

After a convivial dinner at the château, Renault realized that the time had finally come to place himself in genuine danger. The next evening, he was to make the crossing into enemy territory and, for the first time since he had left Vannes, he felt fear. The demarcation line crossed the main road between Bergerac and Bordeaux and ran along a small tributary to the Dordogne called the Lidoire. De la Bardonnie, who had a pass to cross the line, cycled with Renault as darkness fell to a farm which lay just beside the main road and about 500 metres short of the German control point. The farmer and his family then took welcoming charge of Renault, while de la Bardonnie set off on his bike to cross the frontier, ready to receive Renault on the other side.

Meanwhile, Renault was escorted in darkness and in silence

across a large field which ran beside the main road. At one point, his escort whispered to him that next time he should not wear his raincoat. Its colour was too light and potentially visible from the road. They were only about 100 metres from the checkpoint when they reached the stream. It was not too full of water and Renault was instructed to take off his shoes and socks and roll his trousers up to his knees. He slipped on the steep and muddy bank and landed in the water with a loud splash. After an anxious pause, he heard a faint whistle from the opposite bank giving him the all clear and he waded the five-metre width of the stream to the opposite bank. De la Bardonnie was there ready to haul him up the slope and lead him to a small farmhouse tucked beneath the embankment of the main road. Here, another farming family, the Rambauds, greeted him warmly, gave him a glass of blackcurrant brandy and a bowl of steaming water into which to plunge his frozen feet. Renault would get to know the Rambauds well on his future crossings of the line, on one occasion arriving naked at their door having had to remove all his clothes to cross the Lidoire in winter spate.

The river Lidoire, tributary to the Dordogne, at the point where Gilbert Renault would wade across at night to enter and leave the occupied zone. (Edward Wake-Walker

)

After this brief interlude, de la Bardonnie checked the main road for border guards, beckoned Renault across it and led him to a car parked off the road on the other side. It was driven by a doctor friend of de la Bardonnie, who took them westward along the main road and then north to the doctor’s house in the small town of Puisseguin. Here, Renault was reunited with his suitcase which de la Bardonnie had carried across the line on the back of his bicycle, and a sumptuous dinner was served up. The doctor had invited two friends from Bordeaux who offered to help Renault, one of whom, a postmaster, said he had details of all the anti-aircraft gun emplacements.

The next day, Renault set to work in earnest and with an astonishing energy which would characterize his entire mission during the war. In Bordeaux, he did not get any nearer the answers he needed about the U-boat pens, the area being closed off to French civilians. Through a Breton sea captain he knew who was working in Bordeaux, he did, however, make contact with a radio operator aboard a laid-up freighter who agreed to work for Renault if and when he obtained a transmitter. Wasting no time, he then caught a train to Nantes as he had been asked to include the entire French Atlantic coast in his intelligence-gathering and had much ground to cover. Jacques Pigeonneau had mentioned to Renault in Madrid, that the parents of a certain Marc de Saint-Denis, who lived in Nantes, had been enquiring through diplomatic channels about their son, of whom they had heard nothing since his attempt to get to England ahead of the German occupation. Renault was now about to pay these worried parents a visit and tell them their son had safely reached London because, by coincidence, he had also been aboard the Norwegian freighter, the Lista

, on her passage to Falmouth back in June.

The delighted couple were eager to give Renault any assistance they could in Nantes and introduced him to their jovial and obliging wine merchant, Alphonse Lavédrine, whose calls on his German customers had given him close access to the construction site of a new submarine base at St Nazaire. Renault dictated to him the same list of questions he had been given for the Bordeaux base and then set off for his home town of Vannes, where he was able to surprise and delight his mother and sisters by arriving at daybreak at their front door. Learning, to his relief, that the Germans had not bothered his family and had not been concerned about Claude’s and his absence from home, Renault set about further recruitment. Two young men who were friends of the family and whom Renault code-named Lavocat and Prince undertook to work for the network around Vannes, paying

particular attention to the nearby airbase at Meucon, which the Germans had begun to develop.

Renault also went in search of his brother, Philippe who, demobilized, was living with his wife and parents-in-law on the Ile-aux-Moines in the Gulf of Morbihan, earning his keep as a lobster fisherman. Philippe was at sea when Renault got there, but he nevertheless elicited a promise from his father-in-law, a merchant navy captain, to track down a radio operator for the network. Returning to Nantes, Renault discovered that the wine merchant had already completed his questionnaire, which indicated a sizeable installation under construction at St Nazaire. Even if he had nothing yet on the Bordeaux pens, at least he had something of substance to include in his first despatch back to London.

For its delivery, he needed to return across the demarcation line and make his way to Perpignan, where Martha Pigeonneau, the Madrid consul’s wife, had arranged to meet him and carry the documents back across the Spanish border. Renault crossed the line by daylight, this time, and at a different spot to the north of the main Bergerac to Bordeaux road. It meant crossing a road patrolled by German guards and then wading across the Lidoire a little nearer its source. Once again, in the capable hands of the doctor and de la Bardonnie, he made it across without mishap and reached the safety of the de la Bardonnie château.

It was with some pride that he handed a bulging package to Martha Pigeonneau two days later in Perpignan, his first despatch of carefully encoded intelligence reports from behind the enemy lines. Renault was astonished to discover, staying in the same Perpignan hotel as him, two men he had last seen in Passy’s offices in London. One was Maurice Duclos, alias Saint Jacques, the man who had persuaded Passy that Renault was worth engaging; the other was Pierre Fourcaud. Both had been sent on similar network-building missions as Renault and both were now destined to return to London (via Algeria, Morocco and Portugal) to report on their progress to General de Gaulle.

Renault felt he needed to make one more foray into occupied France before returning to Pau on 20 December, in time, he hoped, to acquire a visa to allow him back as promised to his family in Madrid for Christmas. The trip across the line and back went smoothly, and he was pleased to find that his new recruits in Bordeaux, Nantes and Vannes were warming to their task. However, back at Pau, it soon became clear that the Spanish consulate could not obtain his visa until after Christmas. He telephoned Edith with

the sorry news and then decided to pay a visit to Passy’s wife in Grenoble to warn her that her escape into Spain could not be arranged until the end of January. He was back in Pau on New Year’s Eve and found a message at the consulate asking him to ring home urgently. Edith could barely speak; their youngest child, Manuel, just eighteen months old, had contracted diphtheria and had died on Christmas night.

Renault did eventually obtain permission to return to Spain where he was able to witness the birth of his next son in January 1941. The event helped to distract the family from the hammer-blow of their loss and, meanwhile, other issues began to force themselves in on Renault’s grief. First was the operation to smuggle the first radio, codenamed Romeo, into France and to bring Mme Dewavrin and her children back into Spain. This was successfully accomplished by Fourcaud, now back in France, and Pigeonneau, who drove his official car across the border to deliver the radio, hidden in a large leather suitcase and weighing some thirty kilos, and collect the fugitives. Second was the fact that the Spanish authorities were becoming suspicious of Renault. Through his diplomatic contacts, he learned that his arrest was imminent; he would receive one last visa to re-enter France, but could never expect to return.

For the next two months, Renault worked at a feverish pace. Knowing that the Germans had turned their attention away from an imminent invasion of Britain and were instead concentrating effort and resources on a massive U-boat offensive against transatlantic shipping, he was frustrated by how little he was able to pass on about Kriegsmarine

activity on the Atlantic coast. What little information he was getting was losing its currency in the time taken to get reports back to London. The smuggled radio transmitter turned out be badly damaged and was under repair in Marseilles and therefore of no use.

This became particularly galling, as London had now parachuted in a trained operator for use by Fourcaud and Renault, who was kicking his heels at the de la Bardonnie château. Moreover, Renault had recently uncovered and enlisted two priceless new sources of information: one, the former harbour master at Bordeaux, Jean Fleuret; and the other, one of very few French navy officers being kept in employment at Brest. Not only were both able to supply all the answers to the SIS questionnaire, but they could give daily reports of comings and goings of every U-boat and surface vessel of the German navy in both these key ports. Lt Philippon, his Brest source, had even identified a radio operator for Renault, former shipmate Bernard

Anquetil, who, in forced civilian life, was earning a living in a radio repair shop in Angers.

In spite of the risk, Renault was to make one more journey to Madrid. He had found that the Spanish visa office had erroneously given him a return pass and the excellent new intelligence from Bordeaux and Brest needed to be delivered as quickly as possible. When he returned to France, this time on a one-way visa, he had with him on the train not only his entire family but also a second radio transmitter hidden in a diplomatic postal sack provided by Pigeonneau. Thanks to the enthusiastic co-operation of a French customs official based at the Spanish border town of Canfranc, as well as a sympathetic engine driver on the border crossing line, on the same trip, Renault was able to establish a system of getting written despatches back to Madrid.

Edith Renault was delighted to be back in France, where she would at least have a chance of seeing her husband occasionally. They were temporarily accommodated in Pau, but later moved to Sainte-Foy to be near de la Bardonnie’s house. It was here where, at last, the first successful radio contact was made with London; the first of the two transmitters had been repaired but would have to stay in the unoccupied zone and be shared by Fourcaud and Renault, as the second one had also been found to be inoperable and in need of repair in Marseilles. At this time, de la Bardonnie had not only the risk of housing this first radio link and its operator, but he had also just been entrusted with a suitcase containing 20 million Francs (equivalent then to about £100,000), which had been despatched across the border from Spain to sustain the three networks that had now been built up by Fourcaud, Duclos and Renault.

Renault’s network continued to grow with new agents recruited in Bayonne and the Vendée. He had also found an 18-year-old volunteer in Nantes, Paul Mauger, who would prove a redoubtable assistant in the town where Renault had decided to set up his occupied zone headquarters. Meanwhile, Philippon, his navy source in Brest, had some important news to communicate. On 22 March, the two German battle cruisers, the Scharnhorst

and the Gneisenau

, had sailed into the port flying twenty-two flags on their halyards, which denoted the number of allied cargo ships they had sent to the bottom. He was able to give precise details of where they were docked, and these were passed back to London. On 6 April, there was more to report; the Gneisenau

, out in the estuary on trials, was attacked by two British aircraft. One of the aircraft was shot down in a frenzy of flak,

but not before a torpedo had struck the cruiser’s stern and she had limped back into dry dock where repairs would take at least two months. Again, he was able to provide details of exactly where the RAF could find her during her enforced immobility.

For all such information to get back to London, Renault needed to cross the demarcation line again, but first he made a detour to Paris to organize distribution of the networks’ money. His friend Ribes, having shed his earlier defeatism, was prepared to act as treasurer from his office in the capital. At the same time, Renault, who was staying with Duclos in Paris, agreed, against his better judgement, to take back a hefty envelope of courier from his network, in addition to his own. The result was almost a disaster. Renault was arrested by a German border guard while sitting down to eat with the Rambaud family, prior to his crossing of the Lidoire. The guard had seen him further up the road in the doctor’s car and had become suspicious

.

Without time to offload the bulging packets of intelligence, he was marched to a nearby control point, where, by extraordinary self-possession, he was able to convince the officer in charge that, as stated on his carte

d’identité

, he was an insurance inspector carrying out his business at the Rambaud’s farm. Renault was clearly so convincing that the Germans did not even search him, and they let him go. By the time they had had second thoughts and returned to the farm, he was already across the Lidoire and on his way to de la Bardonnie’s château. Rambaud’s story to the Germans was that Renault had been back to the farm and borrowed a bicycle to return to the station to resume his insurance business in the occupied zone.

Over the next few months, there followed a series of successes, narrow escapes and disasters which would characterize Renault’s feverish existence as his influence spread. Always on the move between his contacts, he spent some forty hours every week on trains across the occupied zone and spent most of the rest of his waking hours preparing and encoding reports ready for the next London-bound package. Useful information was now flowing from all his west coast sources, but none more so than from Philippon. Fortunately, the second radio, codenamed Cyrano, had been repaired and Renault, with the help of his operator, Bernard Anquetil, had smuggled the hefty equipment across the demarcation line. Through a friend of his uncle, Jean Decker, in Saumur, he had also set up a transmitting base in a private house in the town. At last, with the help of his young assistant, Paul Mauger, Renault was able to get his regular reports from Bordeaux, St Nazaire and Brest encoded and passed to Saumur for transmission to London in less than twenty-four hours.

Thanks to these new lines of communication, the British Admiralty had information as early as 10 May 1941 that deep-water mooring piles had been laid in the estuary at Brest, ready to receive a large German battleship — almost certainly the Bismarck

— before the end of the month. Then, on 25 May, Philippon was able to confirm the battleship’s estimated arrival in Brest in three days’ time. The Navy would later acknowledge the contribution this information made to ensuring that the Bismarck

never reached her French destination — she was sunk by British ships and aircraft while making for Brest on 27 May.

The Royal Navy and the RAF had further reason to be grateful for Philippon’s efforts two months later, when he was able to inform them that

the Scharnhorst

was putting to sea and heading south on a probable hunt for allied convoys. Renault and his assistant engaged in a frantic dash by train down the west coast to pick up news of any sightings from agents in the various ports. He soon learned that the RAF had found their prey moored at La Pallice, near La Rochelle, and had ensured her inaction for the next four months after she had limped back to Brest. Philippon was constantly disappointed, however, by the small amount of heed paid by London to his reports. He had supplied extensive details of the harbour defences, U-boat pens and berths for the Scharnhorst

, Gneisenau

and Prinz

Eugen

, and had once brazenly walked into the Germans’ port control office during their lunch break and copied the plans of the submarine barrier. To his dismay, he could detect no greater discrimination in the attacks on Brest as a result of his work, and the town’s inhabitants continued to suffer heavy casualties while the key targets remained untouched.

All the time, more people were now coming forward to offer Renault assistance. He had found someone in Paris with links to a German naval officer who was selling the position of U-boats in the Atlantic at 50,000 francs a time. Highly suspicious, Renault nonetheless played along with the source and was astonished to discover that both co-ordinates he had paid for had been correct and the U-boats sunk. Paris was not strictly in his field of operation, being part of Duclos’ territory, but the two network heads worked closely together with Renault agreeing to allow Duclos to use his radio operator, Anquetil, for his messages to London.

Working for two networks and handling the plethora of reports now coming from the west coast of France, Anquetil found himself under extreme pressure in his upstairs room in Saumur. It was not in his nature to complain, however, and even after he reported to Renault that he had recently seen a German radio detector van in the area, he was determined to continue transmitting, especially as he had news of the Scharnhorst’s

damage to report. When Renault, back at his Nantes base, deciphered an urgent message from London that all transmissions should cease immediately as Anquetil had seriously exceeded the security limit, it was too late. The Gestapo had found him at his machine. Anquetil had tried to run from his captors, but was gunned down in the street. Still alive, he was taken into custody for his inevitable interrogation and torture. He gave nothing away, and he was eventually tried and executed three months later on 24 October 1941.

Anquetil’s silence saved what would otherwise have been the obliteration

of both Renault’s and Duclos’ networks. Until now, for both these men, their activities had felt like some rather intense game. The loss of their radio operator changed everything. Someone had died as a result of Renault’s work and he was wracked with remorse. Although he had trusted Anquetil not to talk, he could not be certain of it. Too late, he realized how lax his security had been — Anquetil had been all over France with him and had met just about all of his key agents on both sides of the demarcation line. Renault did all that he could to warn his contacts to hide the evidence of their work, but they all knew their fate rested on one man alone.

As the threat receded, Renault set to work repairing his damaged lines of communication with London. From now on, he would rely on a pool of radio operators who would know only one messenger from the network. At least three much more portable radios were needed from London so that both transmitters and operators could move around, making their detection far less likely. He planned this in co-operation with Pierre Julitte, Passy’s special envoy, who had parachuted into France in May 1941 and was tasked with facilitating the networks’ radio traffic. In the process, Renault made a visit to Paris to pass on a letter to Duclos’ second-in-command, Charles Deguy, giving instructions to their radio operator.

He had a rendezvous at Deguy’s office on 9 August, but the doorman told him simply that he wasn’t there, without giving a reason why. He decided to take the letter to a cousin of Duclos who worked in an office in the Place Vendôme with other members of the network. He walked in on a scene of devastation and was grabbed by one of the two Gestapo officers who were rifling through the papers. Once again, Renault’s imaginative ad libbing saved him. He feigned utter bewilderment and explained that he knew no one in the office except the young telephonist whom, he confided, with suitable embarrassment, he had come to take out for an amorous lunchtime assignation. The Germans dismissed him without even searching him and Renault hurtled out of the building and into the comparative safety of some back streets.

Duclos’ network had been infiltrated by a German double agent, a Luxembourger by the name of André Folmer. Charles Deguy had been arrested, as had Duclos’ brother and sisters and all the others who worked in the Place Vendôme office, except the cousin who had been on holiday. Duclos himself had been in Le Havre and, as soon as word of the debacle reached him, he headed south to the free zone and laid low in the Midi until a safe route back to London could be organized.

Maurice Duclos, alias St Jacques, one of Passy’s first recruits into the Free French intelligence service and the collapse of whose Paris network almost brought disaster to Gilbert Renault in August 1941. (Musée de l’Ordre de la Libération

)

If Renault had not slipped through the Gestapo’s fingers, two networks would have disappeared at a stroke. As it was, one of the trails they were able to follow led to Renault’s uncle in Saumur, who had allowed his photographic shop to serve as Anquetil’s letter box for both networks. Although his wife was eventually freed, he would never return from Buchenwald concentration camp. It had now become obvious to Renault that collusion between networks was highly dangerous.

A great void in intelligence-gathering from the occupied zone had now opened up and Renault acted swiftly to fill it. He moved his centre of operations from Nantes to Paris and installed his sister, Maisie, in an apartment there to relieve him of some of his work preparing courier which, now that he was responsible for the whole of occupied France, was growing by the day. And every day of that late summer and autumn, news — some good, some shocking — would assail him. Four new radios, three of which were highly portable, were successfully parachuted into a field near Thouars,

ready for distribution. His family, long separated from him in Sainte-Foy, had been given permission to re-enter the occupied zone and arrived in Paris before returning to their home in Vannes. Fourcaud, whose free-zone network had begun to thrive, had been arrested by the Vichy police at Marseilles railway station and, worse still for Renault, de la Bardonnie, his vital link across the Lidoire, had been the victim of informers and was now languishing in a Périgueux police cell. So, too, was Maurice Perrin, Renault’s messenger between Sainte-Foy and Pau, thereby removing any means of getting courier out of France.

The police swoop on de la Bardonnie and Perrin had also included a visit to the hotel in Sainte-Foy, recently vacated by Edith Renault and her children, and where they were asking for a ‘Colonel Renault’ and his family. News of another ominous visit, this time to Renault’s mother in Vannes by a man with a poorly disguised German accent claiming to have shared a cell with his uncle in Saumur and asking how to find her son, showed Renault that a net was steadily closing round him. The growing danger to him and his family did not deter him from continuing to build the network from his Paris base during the autumn of 1941. His introduction to François Faure, a demobilized tank commander who soon became Renault’s second-in-command, led to a rich vein of new recruits, thanks to a small band of former soldiers who Faure had brought together to act against the occupation in any way possible.

Until this point, the network had had no name, but Renault now christened it La

Confrérie

de

Notre

Dame

— the Brotherhood of Our Lady. He firmly believed that providence had been responsible for his own recent narrow escapes and that, just as the old kings of France had placed their realm under the protection of Our Lady, he could do no better for all those risking their lives under him than to do the same.

The CND

, as it became known, was now a hugely efficient and productive outfit. It could boast uninterrupted intelligence coverage on the coast from Bayonne to Cherbourg. It was also receiving information from the ports of Antwerp and Boulogne, as well as the area around Reims and the forbidden zone in the east. It was using standardized questionnaires for all the agents so that the information gathered could be collated and corroborated centrally in Paris before transmission. A team of radio operators played cat and mouse with the detector vans patrolling the streets of Paris, and priceless packages of detailed information were building up, waiting for a route back to London. This red-hot courier

included the Germans’ own plans of their U-boat bases in Lorient, Brest, Saint Nazaire, La Pallice and Bordeaux, all gathered in a single coup by Alphonse Tanguy, an engineer working for the Germans. There was also a suitcase of intelligence obtained from a certain Henri Gorce, the only remaining agent of the Paris-based Polish network Interallié

without a price on his head, following its disastrous betrayal by the infamous double agent Mathilde Carré.

By mid-November, London not only wanted urgent sight of this material, they wanted to see Julitte back in their offices and, more importantly, Renault for a debriefing and to issue him with new instructions. Their first move was to send in Robert Delattre by parachute, a radio operator who had been training with Sticky Murphy of 161 Squadron and who was to serve as the network’s expert on Lysander landing operations. He immediately approved a landing field, close to where he had been parachuted and which had been identified by the Thouars-based doctor, André Colas, who had organized Delattre’s reception.

The operation to airlift Renault and Julitte from this field in the moon period just after Christmas 1941 had to be hastily cancelled following the arrest of the doctor who had also been helping the ‘action’ arm of the Resistance. Both Renault and Julitte had been hiding out with their families at a nearby country mansion over Christmas — Vannes was no longer a safe place for the Renault family — and returned to Paris to prepare for the next moon’s attempt. Once again, François Faure’s connections came up trumps. A couple who ran a café in the village of Saint-Saëns, north of Rouen, would provide the safe house for the operation, which would take place in a nearby field.

Faure was keen to introduce Renault to another of his Paris contacts while they waited for the next moon, a well-known left-wing journalist named Pierre Brossolette. Renault the royalist was very dubious about involving a man of such opposing opinions, but was won over by his sharp intelligence and his fierce repugnance at the occupation and asked him to prepare a report on press coverage for London. This link-up with the socialists would prove a significant development in de Gaulle’s efforts to bring disparate factions of the resistance movement together under his Free French banner. Brossolette, in turn, allowed the trade unionist and anti-collaborationist Christian Pineau access to Renault, who agreed, when he got to London, to request a Lysander passage for Pineau so he could pledge his allegiance to de Gaulle

.

The weather thwarted any attempt to land in the Saint-Saëns field during the late January moon period. Renault and Julitte, their relationship already somewhat frayed, had thus endured six nights sharing a single bed in an upstairs room of their hideout café for nothing. But at last, a month later on 27 February, a sufficiently clear night developed and, at around midnight, Sticky Murphy’s Lysander lifted out of a snowy field with Renault, Julitte and their weighty cases of courier crammed into the rear cockpit.

As the plane climbed towards the coast, Renault’s first thought was of Edith and the children, once again abandoned by him in a Paris apartment. Then, as he peered down over the Channel, he was reminded that only a fortnight earlier, the objects of so much preoccupation by the courageous Philippon in Brest, the Scharnhorst

, the Gneisenau

and the Prinz

Eugen

, had slipped through those same waters to safety, undetected by the British navy; and that despite Philippon’s radioed warning on 7 February, of their imminent departure from Brest. What Renault could not know was that only fifty miles to the west of him, another small but telling event in the war was currently in progress.

Several weeks earlier, his network had been asked to supply detailed descriptions of the size and nature of the defences of a German coastal radar station at Bruneval, on the Channel coast between Le Havre and Fécamp. The War Office was eager to discover how far German defensive radar had advanced and planned a paratrooper raid on the installation to capture telling components and to destroy the rest. The same weather window that had allowed Murphy’s Lysander into France had given the raiders their opportunity to act. In a very slick combined services operation, led in the air by Wing Commander Percy Pickard (soon to lead the special Lysander flight), on land by Major Johnny Frost (of later Arnhem Bridge fame) and at sea by Commander F.N. Cook, they achieved their goal, parachuting the airborne forces exactly on target, surprising the German guards so that there was little resistance until the end, and evacuating the paratroopers from the beach below using landing craft.

Apart from anything else, the raid was a propaganda coup demonstrating that Britain was no longer purely in defensive mode against Germany, and that she could strike out effectively, as well. The War Office was first to acknowledge that Renault’s intelligence had been indispensable and so his safe arrival at Tangmere could not have been at a more auspicious moment. Whisked away to London by the possessive Major ‘J’ of the SIS, he was put up in isolated splendour in the Waldorf Hotel, where he was told, to

avoid unwanted attention, he should eat all his meals in his room, even when entertaining visitors. Such circumspection seemed ludicrous to Renault after the risks he had been running in Paris, but he conformed and was gratified to find himself wined and dined not only by the head of the SIS, Major-General Stewart Menzies and the notorious ‘Uncle Claude’ Dansey, but also by General de Gaulle and his intelligence chiefs.

During his month in London, Renault paid a visit to the little church, Notre

Dame

de

France

, off Leicester Square. He had worshipped there often on his previous stay in London and was upset to see that it had suffered considerable bomb damage. Inside, he was even more distraught to find that the much-venerated statue of Notre

Dame

des

Victoires

had been destroyed. Confiding to the priest in charge that he was about to return to France, Renault persuaded him to give him the head, which was all that was left of the statue, so that he could give it to a sculptor friend of his in Paris to reconstruct the remainder to the correct scale. Renault’s precious package that he had jocularly held up before Barbara Bertram in the driveway of Bignor Manor on the night of 26 March 1942 was, of course, the head on its journey to France. But if Renault had appeared carefree to his hostess that night, it was only a gallant show of bravado. The day before his departure, he had learned of the arrest of his entire team of radio operators in Paris. One of them must have talked and he had no idea what awaited him on his return.