CHAPTER 7: THE MAN OF THE LEFT

Christian Pineau’s Story — Part 1

In February 1942, when Gilbert Renault first met Christian Pineau in the basement of Pierre Brossolette’s Paris bookshop in Rue de la Pompe, he seemed to be more fixated by the voluminous fur-lined boots Pineau was wearing than by any part of the earnest discussion he was holding with his socialist friends, Louis Vallon, Jean Cavaillès and André Philip. Pineau, he observed, was offering trite, acerbic remarks which he clearly intended to be taken as words of great wisdom. The four men were, he said, ‘already in the process of reconstructing France to a socialist model’.

If Renault was metaphorically holding his nose in the company of people whose politics were far from his taste, Pineau, in his recollection of the meeting, was more charitable about the newcomer. ‘Renault’s preoccupations’, he wrote in his memoirs, La

Simple

Vérité

, ‘were different from ours. Politics, propaganda, opposition to the Vichy regime, rebuilding the trade union movement were not his province. He saw himself simply as a soldier on an intelligence-gathering mission and had come to see us, after consultation with his bosses, with the sole purpose of organizing my departure’. And it was thanks entirely to Renault and his network that Pineau would find himself waking up to the smell of frying bacon and real coffee wafting from the kitchen of Bignor Manor on the morning of 27 March 1942.

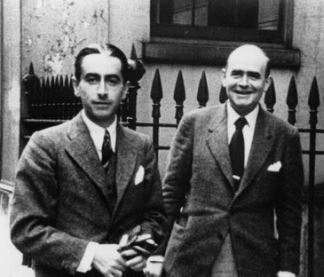

Christian Pineau, a trade unionist appalled by collaborationist attitudes in France. (Gilbert Pineau

)

Christian Pineau was 35 years old when war was declared. The son of an army colonel, he studied law and political sciences in Paris before starting work at the Banque de France in 1931. However, a career in banking

would

lead him in a very different political direction to that of Renault. Pineau grew to detest the inherent power of money and, by 1936, had become the secretary of the federation of bank employees, an affiliate to the national trade union movement, the CGT

(Confédération

Générale

du

Travail

). In 1937, he founded the banking journal Banque

et

Bourse

but, by 1938, he had lost his job at the Banque de Paris et des Pays Bas because he had organized a strike. Instead, he dedicated his time to trade unionism, becoming the full-time secretary of the economic council of the CGT

.

In the chaos that followed the invasion of France in June 1940, Pineau had fled Paris, where he had also been running the private office of his stepfather, Jean Giraudoux, the famous novelist and playwright who was Minister of Information under the radical Prime Minister, Edouard Daladier. After days spent on the roads with hundreds of thousands of other refugees, he was reunited with his family in a small village in the occupied zone, not far from Royan at the mouth of the Gironde estuary. It was here that he and his wife Arlette had their first sight of their German invaders, a procession of motorcycles, machine-guns, tanks, lorries and troops lumbering along the single street. In the silence that followed its passing, they both felt instinctively that their survival lay in opposing this force rather than accepting it. In the house where he, his wife and children and some of his friends had taken refuge, discussions about their country’s predicament lasted long into the night. To his despair, Pineau realized that the split between those who chose to follow Marshal Pétain and those who would resist the enemy and any collaboration would end lifelong friendships.

‘Why shed any more French blood for the English and the City of London? It’s my own country that I’m interested in — that’s why I’m supporting the Marshal.’ So argued one of Pineau’s oldest friends and fellow strugglers against the might of the bourgeoisie. Meanwhile, there were other socialist allies of his who were more ardent even than he in their belief that the war was far from over but that it would not take much more than a year to oust the Germans. At a stroke, the line that divided France was no longer between the left and right but between those impassioned to resist and those who reasoned that appeasement was the way to save the country.

Ever the political animal, Pineau was determined to cross the other line that divided France, Hitler’s demarcation line, to find out whether those not under direct Nazi rule had a different perspective. Lacking any other means of transport, he set off on a marathon bicycle ride to visit a friend from the

union movement in the Dordogne. Crossing the line at that early stage of the occupation meant no more than making a detour via a farm track and, once in the free zone, he found himself an object of fascination to the French military and police, who would stop him on his route and question him about life in that sinister ‘other world’.

At Périgueux, he made an impulsive decision to postpone his visit to the Dordogne and board a crowded train to Vichy to gauge for himself the true motivation of Pétain’s government. The mood among his fellow passengers seemed almost triumphant. At last, France was free from the chaos that socialism had created and they had in Pétain a leader who would put things right. The fact that half of France was under enemy occupation seemed of little concern. One young couple were entertaining their two-year-old child in the congested compartment.

‘Where’s Maman?’ one of them would ask. The toddler pointed to his mother. ‘Where’s Papa?’ No mistake was made. ‘And where is the Marshal?’ This time, to the glee of his parents, the child placed a stubby finger on his heart.

The streets and cafés of Vichy itself seemed to be overflowing with civil servants, young women in neat make-up and countless uniformed police and servicemen. Pineau came across a number of his friends, all of whom talked about a resurrection or a new order and were busy seeking posts in one of the ministries. A professor among them was so bent on saving France that he had gladly accepted the position of floor sweeper in one of the government offices.

One of Pineau’s former trade union colleagues had done considerably better than that. René Bélin had been appointed Minister of Works in Pétain’s government, adding his signature, among other things, to a new law redefining the status of Jews. When Pineau called to see him and asked how he could reconcile his militant union beliefs with such a regime, he was accused of nostalgia and of failing to appreciate how the new order had prevented France from falling into anarchy and offering itself up to the communists.

Back on the Atlantic coast in the occupied zone, Pineau realized that he was almost as affronted by the attitudes of his own countrymen in Vichy as he was by those of the foreign invaders. Since he had been away, however, the latter had further alienated themselves. Someone had cut the telegraph line between Royan and Rochefort, and the Germans had compelled local farmers and other workers to mount a twenty-four-hour guard on the line during the crucial harvest season. At the same time as imposing such disciplinary measures, the Germans were striving vainly to maintain a charm offensive aimed at demonstrating the benefits of collaboration. They were at a loss to understand what the locals found so hilarious about the impeccably arranged line of soldiers queuing in the street day and night in solemn silence for their turn in Royan’s only brothel and, when Pineau’s wife refused to dance with a German soldier when out one evening in the town, his commanding officer came over to demand why. Reminded that there had been this war between them, the officer insisted that it was all over and that they were no longer enemies. The response came back that this still did not make them guests of the country, to which the officer stiffly remarked that the French had absolutely no sense of hospitality.

Christian Pineau with his wife, Arlette on a pre-war summer holiday with his children, (l to r), Bertrand, Claude, Gilbert, Daniele and Alain.

(Gilbert Pineau

)

More certain now of how he felt about his divided country, Pineau returned with his family to their home in Paris. His aim was to bring together as

many senior figures as possible from the disbanded trade union movement who were opposed to the directives coming out of Vichy. He and the former secretary of the civil service union, Robert Lacoste, set to work writing a manifesto that made it clear that there were still people in France who believed in the freedom of the individual, in the principle of human rights and the condemnation of antisemitism and religious persecution of any kind. They succeeded in obtaining the signatures of twelve former secretaries of leading unions, who agreed to promulgate its contents as widely and openly as possible.

They were interested to discover that, while the Germans showed no concern over the manifesto, the Vichy government were greatly upset by it, and Bélin in particular took it as a personal attack, warning Pineau that he was to publish anything similar at his peril. The signatories were delighted by the Bélin outburst and put the Germans’ lack of response down to a policy of divide and rule, nurturing any seeds of conflict between occupied and Vichy France. There was, however, a feeling amongst this group, who began to meet on a weekly basis under the cover name of the Committee for Economic and Union Studies, that if they were to build effective resistance to the Vichy regime and the German occupation, some undercover activity was required.

The question for all embryonic resistance movements at that time — and there were several — was the form of action they should take. So much depended on how long it would take Britain and her allies to launch a counter-assault on occupied France. Other than the French language broadcasts on the BBC, there was no communication between London and those disposed to work underground against the occupation, so all planning was based on guesswork. The optimists, who believed salvation would arrive within the year, thought in military terms, recruiting potential combatants ready to supplement the forces of liberation when they landed. The more cautious, which included Pineau’s committee, were more politically inclined, keen to turn French hearts and minds against their German and collaborationist oppressors and create a mood of resistance which could readily be turned into action when the time was ripe.

And to this end, Pineau and his associates decided to produce a clandestine weekly newspaper aimed not so much at bald propaganda but at circulating real news and information about the state of the nation, wherever it could be gleaned. The only tool they had at their disposal was a portable typewriter, but this was enough for Pineau to put together the first issue of

Libération

, which came out on 1 December 1941. Six copies were produced and each was sent to a different contact who had access to a Roneo machine. It was then up to these people to distribute as many copies as they could to sympathetic colleagues and friends.

It soon became clear to Pineau that there was a considerable thirst for the information he was putting out with reports coming back to him of the news sheet reaching remote parts of the provinces as well as all areas of Paris. But it was a dangerous game he and his friends were playing. The very nature of the task meant that a widespread web of informants had to be recruited and it was virtually impossible to erase all traces leading back to the editor. The situation was helped by a stroke of good fortune when Pineau, realizing he needed to earn some money to sustain him and his family in Paris and thanks to an influential contact of his, landed a job with the Ministry of Supply, with the responsibility of setting up a statistics office. This was an ideal cover for him, not only because it provided him with countless new contacts and sources of information that he could legitimately claim to need for his job, it also gave him unrestrained access into the free zone.

As the influence of Libération

grew, Pineau was somewhat unnerved to discover that other resistance groups were eager to contact him. The little he knew about undercover work told him of the need to keep contact between groups to a minimum to avoid a domino collapse should one be uncovered. However, he could not prevent a number of his acquaintances introducing him to people involved with other underground organizations. One such meeting was with a certain Captain Robert Guédon of Vichy army intelligence who was acting on behalf of Henri Frenay, the leader of a large action-oriented organization. Guédon saw it as his role to bring together all the resistance groups, and was busy forming an armed underground movement in Normandy. Pineau was appalled at his lack of security, pulling lists of people he wanted to meet and copies of his own group’s clandestine newspaper from his pockets, oblivious to the risks of a random Gestapo search at the exit of any Metro station.

Pineau refused to open up to any of these approaches, but they did make him appreciate that the Resistance urgently needed centralized co-ordination, guidance and support but also that this should come from the untainted direction of de Gaulle’s Free French movement in London. And, as time went on, Pineau realized that he should be of considerable value to de Gaulle, acquiring, as he was, a unique, all-round perspective of France under

the occupation. His job made him a regular visitor to Vichy, where he heard every nuance of opinion. There were those who felt it was better to have the Germans than the communists in charge and who therefore wished Hitler God speed on his recently embarked offensive against Russia. Others sensed that the war on the eastern front was an unfavourable turning point for Germany and, with the entry of the USA into the conflict after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, they began to find it easier to suppress their collaborative instincts.

One man who had demanded to see Pineau in Vichy was General Léon de la Laurencie, who, until recently, had served as Pétain’s ambassador to the Germans in Paris. He knew, thanks to the leaky Robert Guédon, about Pineau’s undercover newspaper, poured scorn on the Vichy regime and claimed that he was the natural head of the resistance movement which, come the liberation, would transform itself into the government of the new French republic. When Pineau suggested that General de Gaulle might have other ideas, de la Laurencie smiled indulgently and said that he planned for him to become the military governor in Strasbourg.

One thing that astonished Pineau was the almost total lack of concern in the free zone that the other half the country was under foreign occupation. In Lyons, he attended a meeting of resistance leaders, none of whom showed the least inclination to disguise their activities and all of whom saw their role as opposing Vichy rather than the Germans. Pineau made a point of seeking out an underground group in Clermont-Ferrand, who were also producing a newspaper called Libération

for circulation in the free zone. Here, he was encouraged to find in the group’s leader a sharply intelligent philosophy professor, Jean Cavaillès, who had a far more combatant attitude towards the occupation itself.

Soon after this meeting, Cavaillès moved to Paris to take up a post at the Sorbonne and he was thus able to join forces with Pineau’s group, Libération

Nord

, as it had become known. And it was at their meeting with other resistance leaders in Pierre Brossolette’s basement that Gilbert Renault promised to set up Pineau’s trip to London. Pineau found that some members of his own committee did not share the same enthusiasm as he did for this opportunity to ally themselves to the Free French flag. Although they understood the need for co-ordination and resources, they were wary of handing over control to those who did not understand the risks they were running. The free-zone resistance leaders were altogether more supportive when Pineau travelled south again to tell them of his impending flight, and

asked him to elicit messages from de Gaulle that made it clear that he was a democrat and opposed to all that Vichy stood for.

Returning once more to Paris, Pineau was in for a shock as he left the train at the Gare de Lyon. His father-in-law, Tristan Bonamour du Tartre, was waiting for him with the news that the Gestapo had called at his apartment in the Rue Verneuil that afternoon. René Parodi, a founder member of Libération

-Nord

, had already been arrested. No one else in the group had been approached and this convinced Pineau that he had Robert Guédon to thank for his and Parodi’s exposure. He had heard that many in Guédon’s action group in Normandy had recently been betrayed to the Gestapo and as it had been Parodi who had originally led Guédon to Pineau, it was likely that the Germans had obtained their two names through one of Guédon’s many administrative indiscretions.

There was no question of Pineau staying in Paris at all now, let alone returning to his apartment. He gave himself just enough time to call an emergency meeting of his committee who, although realizing that their lives now hung on Parodi’s silence under torture, promised that they would continue to produce Libération

in Pineau’s absence, come what may. (Parodi died in his prison cell, unbroken by his torturers; Libération

never missed an issue up until Paris’s liberation in 1944). Pineau also consulted Pierre Brossolette about his flight to London that he was now all the more determined to make. The earliest possible time for this, he was informed, was the March moon period, still some six weeks away. The important thing for the time being was to get Pineau undetected across the demarcation line and for his family to follow him as soon as possible.

Thanks to contacts of the CND

network, Pineau made a night river crossing at Chalon-sur-Saône to reach the free zone and eventually arrived in the Vichy offices of the Ministry of Supply with a lot of explaining to do about why he was there. To his relief, he found in the ministry’s secretary-general a man, if exasperated by Pineau’s brush with the Gestapo, not entirely unsympathetic to his predicament and prepared to give him a job as a supply inspector. A few days later, his wife, children and parents-in-law arrived in Vichy having safely negotiated a line crossing in the Cher district, despite his father-in-law’s sneezing fit in a wood close the German checkpoint. Arlette Pineau, who had been suffering considerably with the stress of her husband’s double life in Paris, was hugely relieved they were all now safely installed in Vichy. Pineau could not tell her that, before long, he expected to be back in the occupied zone on an even more dangerous mission

.

The plain envelope delivered to his Vichy hotel told Pineau simply: ‘Tuesday morning, ten o’clock at the bookshop.’ He decided that his wife should know about his escape to England only by a letter, which would reach her after his safe arrival. Instead, he told both her and his employer that he was visiting his son from his earlier marriage, who was living with his godmother not far from Châteauroux. From there, he wrote to the ministry claiming that illness had prevented him from returning to Vichy. He then travelled to Moulins, where he used his Ausweis

(German identity card) to cross the line with a group of factory employees on their way to work. He left the train for Paris at the outskirts to avoid Gestapo surveillance at the Gare de Lyon and spent the night before his rendezvous with Brossolette in a hotel close to Fontainebleau. Two nights later, as recounted in Chapter 1, Pineau would find himself safe under the Sussex Downs.

Hurtling from one rendezvous to the next that he was determined to keep with countless British and French individuals in spite of our constant reminders about the need for strict security, he nonetheless picked up what was required of him as a network head very quickly. Full of dynamism and courage, he absorbed the thousand essential details with astonishing ease and then sought to dispel his fatigue by abandoning himself with childlike joy to the rare distractions of English life.

Such was Passy’s recollection of Christian Pineau when he arrived in London, and certainly Pineau was quick to appreciate the good things about being in a country where, he observed, ‘you could tell there was no foreign occupation and no treachery just by the look in people’s eyes’. If his star rating in the eyes of the SIS did not quite afford him the Waldorf Hotel luxury meted out to Gilbert Renault, a flat in Park Lane and a car at his disposal seemed flatteringly generous to Pineau. Armed with a wad of notes, ration cards, the pseudonym of ‘Major Garnier’ and strict instructions about concealing his real identity from anyone he met — Major ‘J’ of the SIS, or ‘Crayfish’, as Passy referred to him, had been sternly insistent upon this — Pineau joyously set out to buy clothes. He could not resist a little box of coloured soaps from a shop in Piccadilly but, wide-eyed at the choice and quality of clothing on offer, restrained himself from too outlandish a wardrobe as he had been instructed to dress as inconspicuously as possible.

Pineau realized, of course, that such lavish hospitality meant that his

British and French hosts valued his presence considerably and were doubtless expecting to get more than a little in return. As Passy pointed out to him on his first visit to Duke Street (where the Deuxième

Bureau

’s offices had moved under the new name of Bureau

Central

de

Renseignements

et

d’Action

), he was the first Frenchman to come to London from the organized resistance movements. From Passy’s point of view, Pineau was important in a military sense, first because he had links with the combat-oriented groups in France who, when the time came, could be called upon by de Gaulle to join forces with the allied invasion and ensure French participation in her own liberation. Pineau was shocked to hear from Passy that an invasion was still some eighteen months away and wondered how some of the ‘action’ groups in France would sustain themselves for that long.

Passy also had his eye on Pineau as an ideal intelligence network head and, although it was not until the end of his month’s stay in England that he would explain precisely what he wanted from Pineau in this respect, he organized an intense course of training for him at the hands of the SIS, to include encryption, parachute and Lysander reception, movement of men and material, and the protection of radio equipment. When Pineau began to explain to Passy the need for the Free French to show the resistance movement that they understood their particular difficulties under the occupation and explain exactly what they stood for, he was told that it would be better to discuss such matters directly with de Gaulle.

His first of three meetings with the General took place on the evening of his arrival in London in the shape of a one-to-one dinner at the Connaught Hotel. Pineau found himself greatly intimidated by de Gaulle’s cool and somewhat unresponsive demeanour. There were no personal questions about his risky flight out of France, life under German occupation or the safety of his family; he clearly saw anyone prepared to side with the Free French as one of his soldiers with no apparent sympathy for the additional dangers of operating inside France. He wanted to know from Pineau the mood of the nation and its readiness to support him. He understood very little about the resistance movement and found it difficult to be persuaded that only a minority of the population were actively involved in it and that there were plenty who still backed the Vichy government.

Although he was quite prepared to send Pineau back with a message for the resistance movement and the unions, he struggled to appreciate why they wanted to hear assurances that he opposed Vichy-type dictatorships and that France should return to a democratic republic in any post-liberation

government. To him, the priority was the military one of freeing France of German occupation and all collaborators; post-war political solutions were for a later date. Pineau himself did not doubt de Gaulle’s democratic credentials, even though the General clearly blamed France’s defeat on the weakness of the last democratically elected government, Léon Blum’s socialist regime. One Frenchman, the anti-Free French journalist Louis Lévy, whom Pineau met while in London, assured him that de Gaulle was tarred with the same fascist-leaning brush as a number of those working in the BCRA

(Bureau

Central

de

Renseignements

et

d’Action

). Although Pineau did not accept this, he knew many of his socialist colleagues back in France would need contrary evidence in the General’s message to scotch potential rumours.

One thing that disconcerted Pineau in his conversations with de Gaulle was the bitterness he expressed at the attitude of the British to his efforts and the obstacles they put in his way. From the BBC broadcasts Pineau and his friends had so avidly followed, it had seemed that de Gaulle, the British and the Americans were shoulder to shoulder in the fight against Germany. The General’s observation that the allies still viewed Vichy as more representative of French opinion than himself would, he knew, come as a severe blow to the resistance movement. When he was called to meet Major Sir Desmond Morton, head of Churchill’s cabinet office, he found a man who clearly lacked confidence in the influence of the Resistance and who did not wish to believe that the movement would support de Gaulle in spite of Pineau’s assurances to the contrary. He still thought that many in Pétain’s government were playing a double game and would be the most able to rally support for the allies when the time came.

Pineau encountered similar doubts about the popularity of de Gaulle in France when he visited the BBC. The Free French were given only partial control of the French language broadcasts, as it was felt they did not necessarily speak for everyone in the country. While repeating his message that the resistance movement was keen to rally under the Free French banner, Pineau also impressed on de Gaulle’s main broadcaster, Maurice Schumann, the need to express a better understanding than the General was inclined to show of life under occupation, together with much stronger condemnation of the collaborators at Vichy.

Pineau and François Faure were dined out in style by the SIS top brass. General Sir Stewart Menzies impressed upon Pineau that it was through intelligence-gathering that the Resistance could be of most value to the allies at this stage of the war. He urged Pineau to hold onto his position in the

Ministry of Supply for as long as possible, as it was an excellent cover and a valuable source of information. To serve the allied cause best of all, he should forget his reputation among his political allies and proclaim his faith in Pétain. That way, he could get even closer to sensitive information; some of their best agents in France were notorious collaborators, he assured him. Pineau knew that he had a difficult enough task when he got home of rallying the resistance movement under the Free French flag, without also apparently having sided with the enemy.

Menzies and his team were also adamant that isolated terrorist tactics by resistance groups were currently doing more harm than good, bringing, as they did, cruel reprisals against innocent French citizens. Such actions should wait until the eve of the allied invasion, although they would not or could not say when this was planned. By contrast, the Soviet ambassador to London, Aleksandr Bogomolov, who was also keen to meet Pineau for lunch, believed that terrorism by resistance groups helped to destabilize the morale of German troops, and any reprisals only served to turn local populations more strongly against them.

As Passy had observed, Pineau’s hectic sequence of appointments were punctuated by a sampling of London’s entertainments, including a visit to Mirabelle’s in Curzon Street. He was fascinated by the clientele, almost exclusively young uniformed officers with their partners, dining and dancing, apparently without a care in the world. The RAF pilots among them would be flying over Germany probably the very next day; some would never return. Although large volumes of wine, whisky, port and cognac disappeared during the evening, no one showed any signs of drunkenness and when, at midnight, the band struck up ‘God Save the King’, all stood stiffly to attention as though the King himself were present, and then began an orderly exit to the street.

The April moon period was now fast approaching and, once more, Pineau and Faure would soon be putting their lives in the hands of a phlegmatic officer at the controls of a Lysander. It was only when Pineau’s training was completed that Passy revealed precisely what he wanted from him on his return to France. He asked him to hand over his Libération

-Nord

responsibilities to someone else and give all his time to setting up and running an intelligence network from the free zone, reporting directly to him rather than via the SIS. He should keep his job at the ministry at all costs, as this would allow him unique access throughout France and enable him to set up a sister network in the occupied zone in due course

.

Although Pineau had not bargained on agreeing to such an undertaking when he arrived in London, he realized that if he did not accept the mission he would not return to France with what he had come for, namely the money, the means of communication and the support to allow the resistance movement to co-operate and grow. The other object of his visit, a message signed by de Gaulle demonstrating his compatibility with the ambitions of the unions and resistance leaders in a liberated France, was in Pineau’s pocket as he sat at Barbara Bertram’s dining room table, struggling through nerves to eat what was in front of him.

Amid his anxieties about his impending flight and the perilous cloak-and-dagger existence he had agreed to take on for Passy was the concern that, in spite of his repeated representations, de Gaulle had refused to alter his message to underline the iniquities of the Vichy regime. When he arrived at the Tangmere Cottage and was about to board Sticky Murphy’s Lysander, a motorbike rider from London delayed their departure. He handed Pineau an envelope with a revised draft of de Gaulle’s message without any accompanying note of explanation. The changes were small, but each addressed the concerns Pineau had expressed and would make his task of convincing fellow resistance leaders to follow the General that much easier back in France.

When the Lysander touched down at the CND

landing site just over a kilometre outside Saint-Saëns, the reception party was in a state of considerable agitation. A company of German soldiers had arrived that evening in the small town and there had not been time to warn London to cancel the operation. The Tangmere-bound passengers, Pierre Brossolette and his portly CND

companion, Jacques Robert, were shoehorned with their voluminous courier into the rear cockpit in record time. The sound of the plane taking off was enough to wake everyone in the town but, after lying low close to the field for some four hours, Pineau and Faure were led to the café safe house in the town, where they spent the rest of the night undisturbed. The next morning, they caught a commuter bus to Rouen, the German soldiers showing no apparent interest in two passengers with an unusual amount of luggage.

Pineau ran the gauntlet of a short stay with some friends in Paris to give himself time for a secret meeting of Libération

-Nord

, where he proudly produced de Gaulle’s message. Although his friends were pleased to see him back, the majority were less than enthusiastic about putting themselves under the orders of the General. They felt that he could lead them into harm

through his ignorance of the delicate and dangerous nature of operating under German occupation. This reticence, however, did not stop them accepting a sum of money Pineau had decided to set aside from the amount he had been given by Passy to run his network. Pineau also found a replacement editor of Libération

and, most important of all, secured the enthusiastic agreement of Jean Cavaillès to set up and run the occupied-zone section of the new network, which they decided to christen Phalanx

.

Arlette Pineau greeted her husband after his six-week absence from Vichy with the news that she was expecting their second child in November. Of course, she knew where he had been, but his boss at the Ministry of Supply observed that he must have been very ill to have been away for so long and expressed surprise that Pineau had nonetheless put on weight since he was last in the office. Pineau would never be able to explain the glint of malice that crept into the secretary-general’s eye when he went on to announce that the minister had decided to promote him to the top of his grade.

Reaction to de Gaulle’s message was altogether more positive in the free zone, with union and other resistance leaders, including leading members of the pre-war government (whom the message blamed for France’s defeat), seeing it as an effective rallying call to their movement. Pineau used the mobility offered by his job to excellent effect, not just in getting the General’s communiqué widely promulgated in centres such as Lyons and Clermont-Ferrand as well as in Vichy, but in simultaneously recruiting informants to his network from the most fruitful of sources, including even a member of Pierre Laval’s cabinet, who sent minutes of their meetings to Pineau via an intermediary.

As well as money, Passy had promised Pineau the services of a radio operator in Toulouse by the name of Fontaine, and it was with considerable pride that he knocked on his door for the first time to hand over a veritable sheaf of scrupulously encoded messages for transmission to London. Fontaine, a young man, received him with ill grace, acknowledging grudgingly that London had asked him to work for Pineau, but saying he hoped it was only temporary as they had promised him a network of his own. Far from impressed at the volume of Pineau’s intelligence reports, he was horrified, saying it would take him at least five hours of transmission and that most of it should have waited for the next Lysander mission. Pineau was forced to admit to himself that he was probably right when London ordered Fontaine to stop transmitting when he was less than halfway through the pile

.

More support from London arrived by parachute that summer in the shape of two additional radio operators who were also trained in the reception of parachute drops and Lysander flights. One, an earnest young priest, would be based at Limoges and the other, a bearded 40-year-old with the code name Lot, would operate from Lyons. Pineau hoped that Lot would be of particular use to him, as he had been told that the nearby Saône and Rhone valleys were especially suitable for aerial operations. He was disconcerted to find, however, that Lot seemed more interested in his own comfort and remuneration than the job of intelligence transmission. He argued that his dangerous task entitled him to eat in the best black market restaurants regardless of the fact that police officers were their best customers and the risk of arousing suspicion would be great. So Pineau continued to keep him on a tight rein and, although barely co-operative, he managed to run one successful parachute drop of courier and arms in the Beaujolais region.

Pineau began to be concerned that his network was not functioning as well as it could; not because of the lack of good intelligence, but because of the time it took to relay it back to London. The problem was especially acute for Cavaillès in the occupied zone where they had no radios and had to send their entire courier by messenger to Pineau. As he had been asked to organize the reception of a Lysander flight during the late August moon of 1942 and there was no designated return passenger, Pineau requested that he return to London on the flight to organize better lines of communication to and from the north.

Although the Ministry of Supply seemed quite happy for Pineau to be away from his office for weeks at a time so long as his reports kept coming in, and his wife resigned herself to another absence, Lot, the radio operator, was dead set against his departure. Pineau knew why; he feared that his boss would complain to the BCRA

about his poor attitude. When the evening of the operation came, Lot stated categorically to the reception party that he had not received any radioed confirmation that the plane was coming. A little later, however, the BBC, in its coded messages, made it perfectly clear that the operation was indeed on. At the allotted hour, the party set off for the field close to the east bank of the river Saône, north of Mâcon, which they all knew well. It was Lot, in charge of marking out the landing area, who manned the torch at the touchdown end of the ‘L’ and who flashed the agreed recognition letter as the Lysander rumbled into view.

Seconds after landing, the plane, decelerating, suddenly slumped down into the ground to the sound of disintegrating metal. The next moment, the

pilot was out of the plane, gesticulating wildly — the undercarriage had been completely shattered after he had hit a ditch two-thirds of the way along the flare path. There was no way that Lot could have failed to see the ditch when he marked out the field. Guy Lockhart, who was the victim of this unhappy landing, was not going to waste any time. He had no outward passenger, only courier, which he began to bundle into the arms of the Frenchmen around him, telling them in his strong English accent that he would join them on the road in a moment.

Minutes later, there was a loud explosion and the limping figure of Lockhart, silhouetted against his brightly burning plane, came running towards Pineau and his team. Having obeyed the order to set fire to an abandoned Lysander, he was now, for better or worse, putting himself in the hands of the people who had just brought about its incapacitation. As the group made their way silently but swiftly away from the blazing wreckage, visible for miles around, Pineau agonized over what he should do about Lot, trudging along by his side. In his memoirs, La

Simple

Vérité

, he wrote:

My hand was on my revolver. Did I have the right to kill this man? He was responsible for the accident; his betrayal was not to help the enemy but to save his own skin because he was afraid of how he would be judged by his bosses. He deserved to die, without a doubt. Any military tribunal would pass a death penalty. But here there was no judge, no council for the defence. As head of the network I was perfectly within my rights to execute any individual endangering an operation. But was he still a danger? If he had tried to run away, I would have shot him without any hesitation. He was just there, beside me, keeping pace. It would have been so easy simply to lift the gun to the nape of his neck and to press the trigger. But it would be killing a man in cold blood. I had never realized what it meant to make that decision to take a human life, let alone actually to carry it out…

They reached a level crossing and, full of remorse at failing in his duty as he saw it, Pineau knew that Lot would live. There were now other things to worry about: they needed to get to Mâcon without using the roads, which would be alive with police investigating the blaze, and Lockhart needed to put on some civilian clothes. The RAF man had remained surprisingly sanguine, considering he could easily have just been killed. Instead, with only a slight knock on his knee, he seemed almost to be enjoying the situation, treating it rather like a game

.

The decision was taken to walk the ten kilometres to Mâcon along the railway line. When Lot announced that he would prefer not to go with them, Pineau ordered him, in no uncertain terms, to accompany the rest of the party and told him that if he really did not understand his situation, he would readily explain it. They reached Mâcon station without incident, although Lockhart was white with fatigue, and boarded a train for Lyons. Pineau disembarked with Lockhart on the outskirts of Lyons to take the pilot to the house of the underground journalist, Yves Farge, who agreed to hide him for a few days. Before he left the train, however, Pineau handed over a note for one of the party to give to a high-ranking Lyons policeman who was a member of the Phalanx

network. Three days later, this note led to Lot’s arrest and incarceration for black market activity.

Meanwhile, Pineau, who, via a messenger to his trusty Limoges radio operator, was able to tell London that their pilot was very much alive, had a plan which would get both him and Lockhart back to England. A few weeks earlier, Pineau had asked Fontaine to set up a seaborne evacuation for a number of people, including Cavaillès in Paris, who needed to reach London for training and other important liaison work. The operation from the Mediterranean coast near Narbonne was planned to take place in a few days’ time. He calculated that two extra passengers should not compromise the mission.

Lockhart, refreshed after two good nights’ sleep in Lyons, proved quite a handful for Pineau on the crowded train to Narbonne. He insisted on engaging fellow travellers in conversation and playing games with their children and, when Pineau whispered his concerns about his marked English accent, Lockhart dismissed them saying, ‘I’ll just tell them I’m a Canadian’. When the insubordinate Fontaine met them at their rendezvous in Narbonne, he became furious. He claimed he had no space for two extra aboard the Royal Navy-run felucca which was to make the pick-up and ferry the escapees to Gibraltar. He had planned for five: two politicians, an agent from another network, Cavaillès and himself. When Pineau asked who had given permission for him to leave France, he said he had contacted BCRA

direct and, because they would not give him a network of his own and he refused to work as second fiddle, he was going to London.

The upshot of this heated exchange was that all seven would-be passengers took up a hiding place in the sand dunes close to Narbonne-Plage to await darkness and the arrival of the small boat that would get them out to the felucca from the beach. Fontaine had divided up the party into groups

of one or two to aid concealment, and the plan was for them all to head for a flashed signal from a torch on the waterfront when the boat arrived. Cavaillès and Pineau were together and, after peering into the pitch blackness for a considerable time, they saw the signal and stumbled through the reeds and down the dunes onto the beach.

Suddenly, three pistol shots rang out. The two men froze. The sound had not come from where the other passengers were holed up. Somebody shouted something to the left of them and then there was another shout to the right. They had no idea who it was and could see nothing. Taking cover once again in the dunes, they decided to wait. The boat would surely stay out at sea until the commotion had died down. They heard some more shouting that seemed now further away, then silence. After half an hour, they crept out to explore the beach; there was no one; nothing. Cavaillès thought he saw a light go on then off again out to sea but, as they stood at the water’s edge, straining eyes and ears, all they could discern was the sound of wavelets breaking modestly at their feet.

The late moon was coming up now and they knew its light would put paid to any further attempted landing so, bitterly disappointed, they assumed that the others were regrouping somewhere inland and set off along the road back towards civilization. Soon, daylight began to appear and, to avoid any police who may be out early on the road to investigate the shooting on the beach, they took cover in a thicket and slept. It was still early when they woke, but they were thirsty and decided it was now safe to go and look for a café on the road back to Narbonne. But they had broken cover too early. Barely a kilometre along the road, a police car drove past them, then stopped.

Although Cavaillès had all his correct papers, Pineau had sent all his back to Vichy via a messenger before leaving Narbonne for the beach. All he had was a false identity card belonging to someone named Berval. What were they doing out so early in the morning, the two policemen wanted to know, and were they aware that someone had shot at two customs men on the beach that night and then fled? Pineau and Cavaillès claimed they were on a walking holiday and had been nowhere near the beach, but it was when the search of Pineau’s backpack revealed a pair of wet sandals that their story began to lose credibility. The two men, one of whose papers had shown that he was a Paris university professor, while the other claimed he was a Ministry of Supply inspector by the name of Berval, were whisked away in the back of the car, strongly suspected of being dangerous smugglers

.

Their misery would possibly have been compounded had they known that all but one (the other network’s agent whom they were soon to meet at the police station) in the escape party had made it to freedom. There are still conflicting reports about exactly what happened in the darkness, but it seems that one of the customs officers accidentally shot his colleague in the arm, and amidst the chaos, the two politicians, Fontaine and Guy Lockhart, made it to the felucca and eventually Gibraltar. Lockhart was back reporting for duty at RAF Tempsford on 13 September, less than a fortnight after his mishap on the Saône.

Pierre Brossolette, (left) arrives at the Free French intelligence headquarters at 3 Carlton Gardens, London, in the company of Charles Vallin, the politician with whom he escaped occupied France from Narbonne Plage in September 1942. (Musée de l’Ordre de la Libération

)

There is an inexplicable omission in Pineau’s account of his failed escape aboard the felucca on the night of 5 September 1942. Any visitor to Narbonne-Plage today will see a sizeable memorial to the successful evacuation of Pierre Brossolette with Charles Vallin from that spot on the self same operation. Pineau certainly thought he had met everyone due to be taken out that night from among the dunes, so how he and Cavaillès missed the presence of Brossolette, whom they both knew so well, is a mystery.