The Kuttabul had a slightly bizarre history. She was one of the first victims of the Harbour Bridge. Kuttabul was completed in 1922, destined for big things. She could carry up to 2250 passengers. She shuttled them on one of the busiest routes in the harbour: the short distance between Milsons Point at what became the northern end of the Harbour Bridge and Circular Quay ferry terminal near the southern end. When the bridge opened on 19 March 1932, Kuttabul was out of a job. She joined 16 other harbour ferries in the redundancy pool.

When she came off her Milsons Point route, she was used for a time as a concert boat. The concert boats and showboats were a Sydney institution right up until the 1960s.They were invariably big, and offered live entertainment as part of a three-hour cruise on the harbour. The concert boats entertained their packed passenger decks with live music, while the showboats offered a full vaudeville line-up. Kuttabul’s show-business career came to an abrupt end on 26 February 1941 when she was taken over by the Royal Australian Navy, to be re-born as HMAS Kuttabul. The navy tied her up permanently to a mooring at the southeast corner of Garden Island, and used her as a dormitory for sailors who found themselves without a current ship.

Like Sydney ferries to this day, she had two passenger decks. Passengers—or re-housed sailors—entered via a gangplank bridging the shore to the lower deck.They could then climb an internal staircase to the upper deck.There was no exit from the upper deck to shore other than by going back down the stairs. Below the lower deck were the engines. Sailors slung their hammocks on both passenger decks. Their quarters were totally spartan. Cooking and eating facilities were all ashore, as were showers and washrooms.They had card tables and a ping-pong table, but not much else—just a locker, a few lavatories and wash basins, and a place to sling their hammocks.

Kuttabul was fairly loosely controlled, so that it is not possible to say with certainty how many sailors were aboard at any given time, nor who they were.The only certainty from that night is the number of casualties. At 12.30 am on 1 June 1942, Kuttabul was home to at least 31 sailors from three navies—Australian, New Zealand and British.

The Japanese Type 97 Special torpedo was designed to tear a large hole in the armour-plated steel hull of a battleship or aircraft carrier. Its effect on an unprotected 20-year-old civilian ferry largely built of wood was catastrophic. Ban’s torpedo blasted a massive hole in Kuttabul’s hull towards the ferry’s stern, almost breaking the ferry in two. After being tossed in the air by the initial explosion, Kuttabul crashed back into the water and slid straight to the harbour bed.Wintry sea water roared in through the hole in the hull, sinking the ferry instantly by the stern and engulfing the lower passenger deck. The bow remained clear of the water. Any sailors sleeping near the blast on the lower deck were probably dead by the time Kuttabul slammed back onto the harbour surface. The force of the blast from 350 kilos of high explosive detonating at unprotected close quarters was simply not survivable. The explosion blacked out all the lights on Garden Island, and cut the telephone cable. It started a small fire on the wharf.

At the Australian National Maritime Museum in Darling Harbour, Sydney, there is a dramatic voice tape from one of the survivors, painting a vivid word picture of the scene on board. He was quartermaster aboard the Kuttabul that night, and the tape tells us nothing about him other than that his name was Ed. He was lightly injured in the explosion. Here are his words:

All I can remember was when I was hit I went down on the deck. You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. I just covered up. I’d just come back from the Middle East and I thought: this is an air raid. I heard water running and I said gee, it’s time I got out of here.

We all sort of made a move then. I don’t know what window we got out of. Three or four of us scrambled through and we pulled ourselves up onto the wharf. Next thing we looked around and the Kutta was more or less right on the bottom. So there was nothing much we could do, only turn around and help get the injured.

We took them up to the sick bay on Garden Island.The Petty Officer came and said: ‘Ed, you’re the quartermaster here. You should know all the chaps on board.’ I said: ‘I’ll give it a go, but they’re coming and going like flies.They might be here 24 hours and they get a draft straight away.’He said:‘I’d like you to come up and try to identify some of the bodies up there in the sick bay.’

He took me up there.This will stick in my mind the rest of my life. There was one chap there: all the skin of his face, you could just lift it up, straight off. Embedded itself in my mind, that did.

There were extraordinary acts of courage that night, and extraordinary tales of luck, good and bad.

Bandsman M.N. Cumming was, as his rank implied, not a fighting sailor. He was a musician. He had boarded the Kuttabul only five minutes before the explosion. The blast itself caused him a few cuts, but he was otherwise uninjured. He thought the ship had been hit by a bomb. Instead of heading for the safety of shore, then only a metre or so away, he stripped off and dived repeatedly into the bitterly cold,watery wreckage, ignoring shattered glass and jagged woodwork in a frantic search for survivors. He is credited with rescuing three critically injured sailors.

Engineer Captain A.B. Doyle and Commander C.C. Clark had been ashore on Garden Island when they heard the explosion.They raced to the scene and waded straight into the deep water. In pitch darkness they ignored the dangers of splintered decks and other lethal hazards to rescue shocked and dazed sailors, and lead them to safety. Cumming, Doyle and Clark were all singled out for mention by Rear Admiral Muirhead-Gould in his report, with the implication that they all deserved medals. They did.

They had no monopoly on courage.Ordinary Seaman L.T. Combers was below decks when the explosion knocked him off his feet. He smashed through a window to safety outside the ferry.Then he heard a cry for help, and saw a sailor slipping below the surface with the sinking wreckage. Although he was now safely clear, he dived back into the danger area and managed to drag the stricken sailor to the safety of a nearby motor launch.

Petty Officer J. Littleby usually slept aboard the Kuttabul. That night he had accepted a friend’s invitation to bunk down in a small motor boat tied up nearby. The blast and shock wave almost swamped the tiny boat. However Littleby managed to keep it afloat and bring it up alongside Kuttabul. Three injured sailors owe him their lives. Littleby’s regular sleeping quarters on the Kuttabul were totally demolished in the blast. If he had been asleep in his regular place that night, the death toll might have risen by four.

Others were plain lucky. Able Seaman Neil Roberts had been on sentry duty on land. He was due to be relieved at midnight. When his relief failed to materialise, he went to look for him aboard Kuttabul. As a way of apologising for failing to turn up for duty on time, the chastened relief offered Roberts his bunk on the more pleasant upper deck, instead of Roberts’ usual bunk on the lower deck. Roberts accepted. And lived.

Able Seaman Charlie Brown had also been on sentry duty. He had heard the gunfire and explosions on the harbour, and wondered what was happening. He went off duty at midnight and by 12.10 was asleep in his bunk on the lower deck near the bow. His next memory is of a gigantic orange ball of fire, and of being blasted between a row of wash basins through the ship’s side and into the water. Debris rained down on him, trapping him. He was slipping into unconsciousness when someone saw his hand flailing in the water. He was dragged to safety.

Able Seaman Colin Whitfield, a New Zealander, had one of the most remarkable stories of the night. He was climbing out of his hammock, with his feet on the deck, when the torpedo struck. When he tried to move he found his legs were useless, although he could see no injury. He had to descend the staircase to get to safety, which he managed by bumping down on his backside. At this point he blacked out, and remembers only that somebody helped him to the jetty, then carried him to the sick bay.

His next memory is of waking up in hospital at 3 am, with the surgeon bending over him saying something like: they’ll have to come off. The surgeon then told a colleague that the anaesthetist had gone home for the night so they’d have to come off in the morning. In the meantime an orderly was told to make Whitfield comfortable.The orderly took it upon himself to bind up Whitfield’s feet.Although the skin was unbroken, every bone inside was smashed. In the morning the surgeon was fulsome in his praise for the orderly. He had done exactly the right thing.Whitfield’s feet had been bound in such a way that the bones might re-knit.The surgeon thought the feet might be saved.They were.

Others were less lucky. Petty Officer Leonard Howard, from Penrith west of Sydney, wanted to meet his wife next day. So he swapped duty with another sailor, and stayed aboard Kuttabul. He was killed.

Stoker Norman Robson was due to go on leave later that morning. Before going to sleep, he posted a letter to friend, including the words: ‘You can never tell with this place.Anything might happen.’The friend received the letter three days after Robson’s death.

Ordinary Seaman David Trist had survived the sinking of HMS Repulse six months earlier, on the second day of the Pacific war. He did not survive the sinking of the Kuttabul.

Rear Admiral Gerard Charles Muirhead-Gould, photographed in Sydney.

An excellent aerial picture of USS Chicago, showing the four Curtiss Seagull aircraft strapped to her deck.

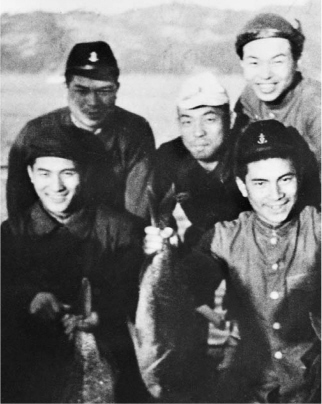

Japanese midget sub mariners photographed in an informal moment during training. Matsuo is front row, left, while Chuman, rear left, peers over his shoulder.

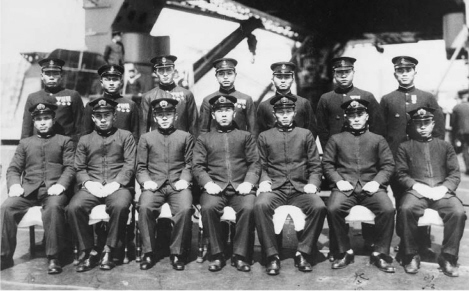

The Japanese midget submariners in formal pose before the raid. Commanding officers are in the front row with their crewmen behind them. Ban is front left, Chuman is third from left and Matsuo is fi fth from left.

Lieutenant Reginald Andrew, commander of the channel patrol boat HMAS Sea Mist.

Warrant Offi cer Herbert (‘Tubby’) Anderson, commander of HMAS Lolita.

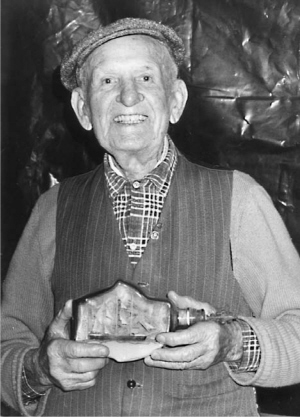

Jimmy Cargill, the Maritime Services Board nightwatchman who fi rst raised the alarm.

The boom net after completion, viewed from the western side. On the night of 31 May 1942 the curved boom gate on the centre right of the picture had not been fi tted. Only the centre section stood ready to block ships and submarines. Note the Pile Light just to the left of the Western Gate and on the harbour side. Chuman’s propellers became tangled in the net opposite the pile light, in 13  fathoms of water.

fathoms of water.

Roy Cooté (left) ‘suited up’ and ready to dive. The identity of the second diver is not known, but it may well be Lance Bullard. (Photograph courtesy Cooté family collection.)

This picture has never previously been published. It shows Chuman’s midget seconds after it was raised from the harbour bed, with the coils of the boom net clearly shown tangled around the sub’s propellers.

(Photograph courtesy Cooté family collection.)

Postcard produced by the Royal Australian Navy and sold as a souvenir of the submarine attack. This particular postcard shows the fearful beating from depth charges suffered by Matsuo’s midget. The massive dent behind the conning tower is clearly the result of a depth charge detonated at very close range. It may well be the outcome of Reg Andrew’s first attack in Taylors Bay.

A dockyard worker clearing wreckage from the devastated depot ship HMAS Kuttabul. (Photograph courtesy Cooté family collection.)

Matsuo’s midget shortly after it had been recovered from Taylors Bay. This photograph clearly shows the bow cage bent inwards on both sides, with the bow caps jammed and blocking any possible release of the two torpedoes.

Channel patrol boat HMAS Sea Mist, whose crew dropped the fi rst depth charge on Matsuo’s midget in Taylors Bay. Note the lone machine gun, and depth charges strapped to the rear deck.

The scene on 8 June 1942 after the shelling of the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney. This photograph was taken at the corner of Fletcher and Small streets,Woollahra. The map given to the author by the Australian War Memorial records this shell as ‘exploded, no damage’ but the contemporary photograph suggests the outcome was rather more destructive.

The centre section of Chuman’s submarine on its trailer journey around Australia. The navy chose to fl y the White Ensign naval fl ag over their trophy.

The composite submarine, assembled from Matsuo’s bow and the mid and stern sections of Chuman’s midget, is the centrepiece of the most popular display in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. It is just possible to see the denting of Matsuo’s bow caused by the steel cable used to haul it up from the bottom of Sydney Harbour. Although much of the exterior of the submarine has been restored, the War Memorial has left the centre section as it was found, ripped open by the force of Chuman’s scuttling charges.

The stern section of Matsuo’s midget. This section broke away from the main body when the submarine was being dragged along the harbour bed to shallower water in Taylors Bay.

The bow of Matsuo’s submarine, part of the special display at the Australian War Memorial.The bow cage has been straightened and the bow caps have been repaired and locked back into place.

This contemporary photograph, taken just off Bradleys Head on Sydney Harbour, shows Garden Island as it might have looked through Ban’s periscope. The Kuttabul was moored in front of the low pink building on the centre left.The buoys’ positions have changed since 1942, but the large white buoy on the extreme left of the picture is not far from the position of No. 4 buoy, where the USS Perkins was tied up on the night of 31 May 1942. From this position, Ban would have faced Perkins’ stern.

Ban’s midget at rest on the seabed off Newport Reef, Sydney. A diver’s light illuminates a shoal of fi sh below the wrecked conning tower. The large hole in the hull is caused by corrosion after 64 years under water, and indicates the fragility of the wreck.Two lines can be seen on either side of the conning tower, both left behind by commercial fi shing boats snagging their fi shing lines and nets over the years. (Photograph courtesy 60 Minutes and No Frills Divers).

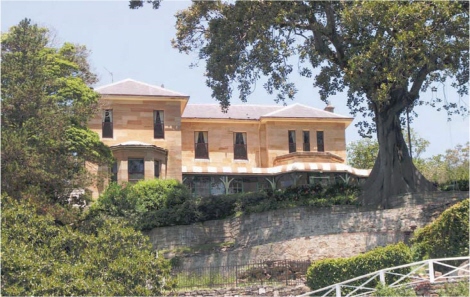

The graceful ‘Tresco’ still adorns Sydney Harbour’s foreshore at Elizabeth Bay. Rear Admiral Muirhead-Gould could walk down the cliff path to a small wharf, where his barge would deliver him to his headquarters on Garden Island, a few hundred metres away.

Margaret Coote (née Hamilton) peers intently at the conning tower of Matsuo’s submarine, on display at the Naval Heritage Centre on Garden Island, Sydney. This picture, taken in October 2006, records her fi rst sighting of the submarine for more than 60 years: it last appeared in her life in June 1942, when she watched it being dragged to the surface in Taylors Bay. Previously she had seen its periscope gliding into Taylors Bay, and had watched the depth charge attack that led to its destruction.

This photograph of the western Pile Light was taken from the deck of the Manly ferry on its regular route via the Western Channel from Manly to Circular Quay shortly before its collapse at 4.30 pm on 12 December 2006. Its role in the Battle of Sydney Harbour—Chuman reversed into the boom net while submerged, almost certainly after colliding with the Pile Light—has never been given proper recognition. The old light, rebuilt in 1947, was at least as effective as the newfangled net in foiling Chuman’s attack.

Sydney is packed with reminders of its World War II past. This concrete slab on Laings Point, an easy walk from the Watsons Bay ferry wharf and Doyle’s Restaurant, was the anchor for the eastern end of a boom net that stretched across the harbour to Georges Head. Today it is marked by a small plaque, including a brief description of the net’s role in the Battle of Sydney Harbour.

In all, Ban’s torpedo led to the death of 21 sailors aboard the Kuttabul, 19 Australian and two British. Of those who died, 19 were killed aboard the ship; one died later in hospital; one sailor was missing. There were 10 injured, some seriously. The death toll in the Battle of Sydney Harbour had now risen sharply, from two to 23.

At about 1 am, half an hour after the torpedo struck, Kuttabul’s bow slid under the water, leaving only her wreckage-strewn upper deck slightly exposed.

In the wake of the blast, bedlam returned to Sydney Harbour.There was wild shooting from all directions. It was a bad night for floating bits of wood, old packing cases, buoys, broaching fish, and fleeting shadows: all were sent ruthlessly to the bottom in a hail of tracer fire and heavier shells.

Some ships fired aimlessly into the air, believing this was an air raid and they might as well be seen to be doing something. Others felt obliged to sound off with klaxon horns or sirens, adding to the mindless pandemonium. The crew of the Channel Patrol boat HMAS Marlean, which had slipped its mooring earlier in the night and moved down the harbour to see what the fuss was all about, sheepishly admitted they had fired at their own shadow in Athol Bay, which they saw projected onto the harbour shore by the roving searchlights. Next day they scoured the papers for any report of casualties among the animals at Taronga Park zoo, which had been right in their line of fire.

This had no effect whatsoever on the two Japanese midget submarines still alive in the harbour. Matsuo continued to hide on the harbour bed just inside the entrance, awaiting his chance. He must have heard the detonation from Ban’s attack, but he will not have known whether it was caused by another midget’s torpedo or by some other explosive device like a depth charge. If it was a torpedo, he will not have known what damage resulted. He must have hoped that whoever had triggered the explosion had left him some worthy targets to pursue when he could finally get under way.

Meanwhile, Ban continued to creep towards the harbour exit and safety. From his periscope Ban could see the Chicago still serenely tied to her moorings.With both torpedoes spent, he had nothing left to fire at her but an 8 mm pistol. Time to say farewell to Sydney Harbour, and head for the open sea.

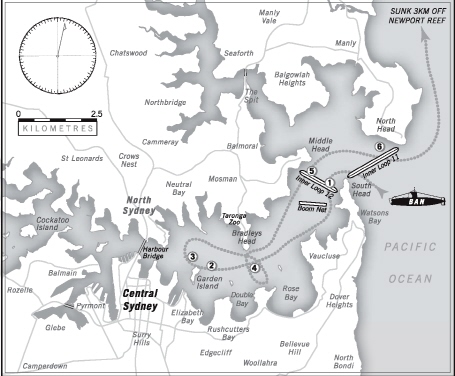

The track followed by Ban’s midget is fairly well established. The timings are: (1) 9.48 pm, crosses Inner Loop 12, leaving a clear trace; (2) 10.50 pm, fired on by USS Chicago, and submerges; (3) 11.10 pm resurfaces, fired on by USS Chicago and HMAS Geelong, submerges; (4) 12.29 am fires two torpedoes at USS Chicago, both of which miss, but one sinking HMAS Kuttabul; (5) 1.58 am crosses Inner Loop 12; (6) 2.04 am crosses Inner Loop 11 and exits Sydney Harbour.

The bedlam in the harbour was well mirrored by chaos on land. Radio stations broadcast urgent appeals to sailors to return to their ships.Taxi drivers were asked to scour the streets, cinemas, theatres, pubs, bars, nightclubs and brothels in a hunt for sailors to be rushed back to their stations. Police cars joined in the hunt for roistering crews.

Among the civilians, wild rumours spread at amazing speed. The invasion had started. The Japs were here. Even those who should have known better joined in the madness. A caller to a Sydney radio station remembered a particularly hysterical air-raid warden on his street, knocking on doors and rousing the occupants with an urgent message: ‘There’s an armada of aircraft.They’re coming down.They’ve flattened Brisbane and they’re now over Gosford, and soon they’ll be bombing Sydney. Get the children under the table, in the hall, with a mattress on top. Good luck! Good luck!’

The 19-year-old Dorothy Levine had been on duty at the American Service Club in Phillip Street in Sydney’s Central Business District. She was trying to make her way home by taxi to Vaucluse. Just as she was passing Rose Bay Police Station she saw tracer fire on the harbour followed by booming explosions.

I said to the taxi driver: my goodness, fireworks in the middle of wartime. I think it’s ridiculous.

Then people came running out of all the units along the waterfront.We were told to go immediately to the nearest air raid shelter.We could hear boom, boom, boom, then a huge, loud explosion.

We were very frightened because it just wasn’t natural to have all that light. The whole sky was lit up with searchlights. There seemed to be a lot of people. They just came from nowhere. Everyone was running all over the streets, not knowing what was going on.

Rahel Cohen, a 23-year-old secretary serving in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, had come to Sydney from Wagga Wagga on leave.At 12.15 am she caught the last ferry from Circular Quay to Athol Wharf near her parents’ home in Mosman. There were only four people on board— Rahel, an army officer Captain Ross Smith, the ferry captain and the ferry’s engineer.

The ferry captain decided to take a slightly longer route this night. The Athol Wharf ferry normally tracked north-east from Circular Quay, passing to the north of the small harbour island of Fort Denison.

However, an hour earlier the captain had heard shooting and general uproar from the direction of Garden Island and the USS Chicago, so he decided to take his ship south of Fort Denison and close to Garden Island to see what was going on.

The ferry had passed both Garden Island and Chicago and was about to turn left towards Athol Wharf. ‘I was standing on the lower deck talking to the army man when I said: what’s that? It looked like a silver thing, going under our ferry,’ Rahel recalls. It was Ban’s first torpedo, 5 metres below the surface and well under the ferry’s hull, on its way to the Kuttabul. ‘The Army captain saw it too. He pushed me down on the deck and fell down on top of me to protect me.Then there was a crash, of course.The torpedo had come up on the other side of our ferry and killed all the sailors. I remember the army fellow said to me: don’t look.’ Within seconds all hell broke loose. Searchlights flashed on all over the harbour. Rahel heard the ferry captain poke his head out of the wheelhouse and say:‘Let’s get to hell out of here. Get inside.We’re going to try to rush across.’

The ferry raced across the harbour to Athol Wharf. By the time it tied up, the tram which normally met it and carried the ferry passengers up the steep hill to the suburb of Mosman had fled.That night Rahel Cohen walked home, escorted in the darkness by the gallant Captain Smith.

Muirhead-Gould left the boom net in his barge and went straight to his headquarters on Garden Island. Clearly his first job was to find out what had happened.This will not have taken long. By now there were plenty of people who knew it was a torpedo attack.

Jimmy Mecklenberg arrived on Garden Island in the Chicago’s Captain’s gig at about the same time as Muirhead-Gould. His account of his encounter with Muirhead-Gould is a masterpiece of tact. ‘The Admiral was well aware that there were submarines in the harbour,’ Mecklenberg recalled. ‘He suggested that I should tell my commanding officer to take the US forces to sea.’There is another version of this story, which suggests that Muirhead-Gould’s words were a great deal more terse and to the point. In this version, his message to Bode was only five words long.‘Get out of my harbour.’

However it was expressed, the order to get under way was repeated around the harbour. The Indian Navy corvette HMIS Bombay and the Australian Navy corvette HMAS Whyalla were ordered to get moving, while the long-suffering USS Perkins once again slipped her mooring and set out to screen Chicago while the cruiser built up steam ready to head out to sea. The anti-submarine vessel HMAS Bingera was ordered to switch her search from the Harbour Bridge area and sweep the harbour between Garden Island and Bradleys Head, offering further protection to Chicago.

None of this was easily achieved.With the general overload of communications, very often there was no way to pass orders to the ships by radio.An officer was dispatched in a speedboat from Garden Island to go around the harbour advising all ships to make ready to go to sea, or to take up anti-submarine duties in the harbour.

At 1.10 am Muirhead-Gould sent out a general message: ‘Enemy submarine is present in the harbour and Kuttabul has been torpedoed.’ It was now five minutes short of five hours since Jimmy Cargill had spotted Chuman’s sub in the net.Yet this message from Muirhead-Gould was the first to ships in the harbour giving them any accurate information about what was going on.

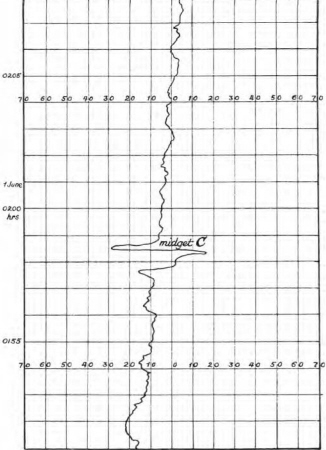

At 1.58 am Inner Loop 12 recorded its third small, unexplained blip of the night.This was immediately taken to be a third submarine entering the harbour. In fact it was Ban on his way out.

Trace left by Ban (I-24’s midget) on Inner Loop 12 as he leaves the harbour at 1.58 am.

More and more ships got under way. HMAS Canberra, on four hours’ notice at no. 1 buoy, was ordered to sea at 1.15 am. The Dutch submarine K9, moored alongside Kuttabul, where she had taken a lot of damage but injured only one sailor, was towed up the harbour and out of harm’s way at 1.20. The Australian minesweeper HMAS Samuel Benbow moored off Watsons Bay reported at 1.25: ‘Crew at action stations. Raising steam.’ At 2.14 Chicago reported: ‘Proceeding to sea.’ The Australian corvette HMASWhyalla informed Garden Island at 2.30: ‘Slipped and proceeding to sea.’

It is worth standing back a moment and considering these decisions. Large ships like USS Chicago and HMAS Canberra are at a massive disadvantage in the tight space of a harbour, particularly a narrow harbour like Sydney’s.There were enemy submarines on the loose, so the natural response of both Muirhead-Gould and the respective captains was to take their ships away from the immediate danger and out to sea where they could fight. But that raised a massive question: if there were midget submarines in the harbour, how did they get to Sydney? And if the answer was: on the backs of larger submarines as they had done at Pearl Harbor, then where did that leave the escaping ships? The answer was: in huge trouble. There were five massive ‘I’ class Japanese submarines, all armed with an arsenal of their justifiably feared Long Lance torpedoes, lurking in the deep water outside Sydney Harbour.

We can only guess at Sasaki’s motive in not leaving at least one or two of his mother submarines outside the harbour entrance with orders to pick off any large ships trying to escape.After all, that had been his tactic at Pearl Harbor six months earlier. In his official account of the raid G. Hermon Gill concluded: ‘Luck was certainly on the side of the defenders.’ Luck was surely with them now.As the ships steamed towards the open ocean, the mother subs had moved off south towards the rendezvous point at Port Hacking. So no Long Lances lay in wait for Chicago, Perkins, Canberra, Whyalla and all the other warships racing for the open sea.