King was shouted down by anticommunists in his talk on “The Other America” in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, on March 14, 1968.

Let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness

. . . I may not get there with you. But I want you

to know that we as a people will get to the promised land!

—KING IN MEMPHIS, APRIL 3, 1968

WHEN KING LEFT MEMPHIS ON MARCH 18, HE FELT euphoric. The movement he had struggled to build, uniting elements of labor, religion, the black community, students, and whites in and out of unions, seemed to be on track. Memphis made the Poor People’s Campaign a true movement of the working poor. On March 19, a reenergized King toured Batesville, Marks, Clarksdale, Greenwood, Grenada, Laurel, and Hattiesburg (where he met his audience at midnight). In these Mississippi Delta towns, he confronted the desperate poverty of the unemployed poor. In Marks, he told an interviewer, “I found myself weeping before I knew it. I met boys and girls by the hundreds who didn’t have any shoes to wear, who didn’t have any food to eat in terms of three square meals a day, and I met their parents, many of whom don’t even have jobs.” Conservatives complained that the poor were on welfare, but King found that in Marks the really poor had no income at all. “I literally cried when I heard men and women saying that they were unable to get any food to feed their children.”

In Marks, a town of 2,500, poor people had been cast off from the cotton economy. Landlords mechanized away their jobs. Poor people lived in shacks without plumbing, lighting, or ventilation in one of the most humid and hot places in the world. Some subsisted on berries, fish, and rabbits. Yet, remarkably, this is where King envisioned a core constituency for a poor people’s solidarity movement. As Stokely Carmichael had observed when he worked with King in the March Against Fear in 1966, King was at ease, even happy among the poor people of the Delta. In Mississippi King found a core of poor people who would go to Washington in May and afterward put one of the largest contingents of black elected leaders into office in the United States.

As he viewed the horrible conditions of the black poor in Mississippi, King spoke as strongly about racism as any black nationalist. “The thing wrong with America,” he told a rally in Laurel, “is white racism. White folks are not right. . . . It’s time for America to have an intensified study on what’s wrong with white folk . . . anybody that will go around bombing houses and churches, there’s something wrong with him.” King said the land was beautiful but “white folk want it all for themselves.” Speaking in the idiom of the black poor he added, “They don’t want to share nothing.”

Slavery and the overthrow of Reconstruction provided his frame of reference. Emancipation, King said, produced “freedom and famine.” It released slaves from bondage, but “America did not give the black man any land to make that freedom real.” Africans did not come to America as many immigrants did looking for freedom; rather, they were ripped from their freedom in Africa to work without wages in America.

King recalled a conversation with a white man on a plane who said blacks should lift themselves up by their own bootstraps like other immigrants. The “bootstrap philosophy” of American capitalism, as portrayed by fiction writer Ayn Rand and some economists, held that anyone could advance him- or herself through individual initiative. King recalled telling the man, “It’s a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to lift himself by his own bootstraps.” Few black people received the kinds of government support—the New Deal’s low-interest home loans, the homesteads and land grant colleges and subsidies, and federal land acquisitions and military protections that gave birth to railroad and oil magnates in the West—that had boosted some immigrants and the white middle and upper classes. African Americans had accumulated little capital, while black labor exploitation had helped to produce some of the richest people in the world. In Sunflower County, Senator James Eastland, one of the wealthiest plantation owners in Mississippi, received hundreds of thousands of dollars in subsidies not to plant crops. Meanwhile, agricultural working people like Fannie Lou Hamer ended up desperately poor and black farmers lost their lands.

In contrast to the immigrant “self-made man” stereotype, King spoke of a man kept in prison for many years and then released when it is discovered he is not guilty. “And then you just go up to him and say, ‘Now you are free.’ And don’t give him any bus fare to go to town. Don’t give him any money to get some clothes to put on his back. Don’t give him any money to get on his feet in life again. Every code of jurisprudence would rise up against this. And yet, this is exactly what America did to the black man.”

In Quitman County, perhaps the poorest county in America, King pointed out that whites had tried so hard to keep blacks down that they had stifled economic development and education for themselves. Just as black poverty could never be eliminated without ending racial injustice, white poverty would continue as long as poor people allowed themselves to be turned against each other on the basis of race. King said the freedom movement sought “economic justice for the poor” regardless of race. Yet the only white ally King saw in Mississippi was a seemingly inebriated man named Mr. Mobley who walked up to him and slipped a hundred-dollar bill into his hand, and then left.

King in his “people to people” tour for the Poor People’s Campaign warned that the second phase of the freedom movement would be harder than the first—hard to imagine after what people went through in the first phase. “It is much more difficult to eradicate slums than it is to integrate a bus,” or to create jobs and incomes for all the nation’s people, he said.

King ended his southern tour on March 22, in Albany, Georgia, a place where he had repeatedly gone to jail for demanding civil and voting rights. King declared the Poor People’s Campaign would gather the sick, the hungry, the poor in a shantytown in the nation’s capital that would let “the whole world know how America is treating its poor citizens.” African Americans would be joined by Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Indians, and Appalachian whites. It would be a “great camp meeting,” with freedom schools teaching people’s history, with better food than poor people normally get, and with music. As SCLC staff member Jimmy Collier sang to King’s audiences, “I’m gonna walk the streets of Washington one of these days.” King told audiences, “If you can’t fly, run. If you can’t run, walk. If you can’t walk, crawl, but by all means, keep moving.”

King too had to keep moving, as his time to serve the people ran out.

* * *

IN THE EARLY hours of March 24, King waited in the Atlanta airport for his flight to Memphis, where he planned to lead a mass march, perhaps even a general strike, on behalf of the sanitation workers. He waited in vain. A huge snowstorm blew in, shutting down the airports. James Lawson in a phone call with King joked that God must have called a general strike: the storm completely closed down Memphis. King rescheduled to come to Memphis on March 28. Before his return to Memphis, King spent four days recruiting and speaking in upstate New York and the New York City area. He intended to go to Memphis on the night of March 27, but he was too exhausted. “Martin must have been so fatigued he was almost in a daze,” Andrew Young recalled. King told a reporter he had been getting two hours of sleep a night for the last ten days. He put off his flight to Memphis until morning, but then stayed up arguing late into the night with SCLC board member Marian Logan. She argued that his Poor People’s Campaign would lead to riots and repression and swing more white voters to the right in the 1968 elections. He too was worried about this, but insisted that she support the campaign. He drank and smoked and argued, and hardly slept. She feared King was “losing hold.”

After a police attack and a riot on March 28, 1968, the Tennessee National Guard occupied Memphis, but members of AFSCME Local 1733 continued to march.

King typically tried to be in two places at once. He planned to make a quick trip to Memphis, lead a march, then leave that same day for meetings in Washington, D.C. He got up early, but his plane was late. Everything started to go wrong. Exhausted, frustrated, agitated, King did not arrive at the Memphis airport until 10:30 a.m., when AFSCME organizer Jesse Epps picked him up in a white Lincoln Continental borrowed from a black funeral home.

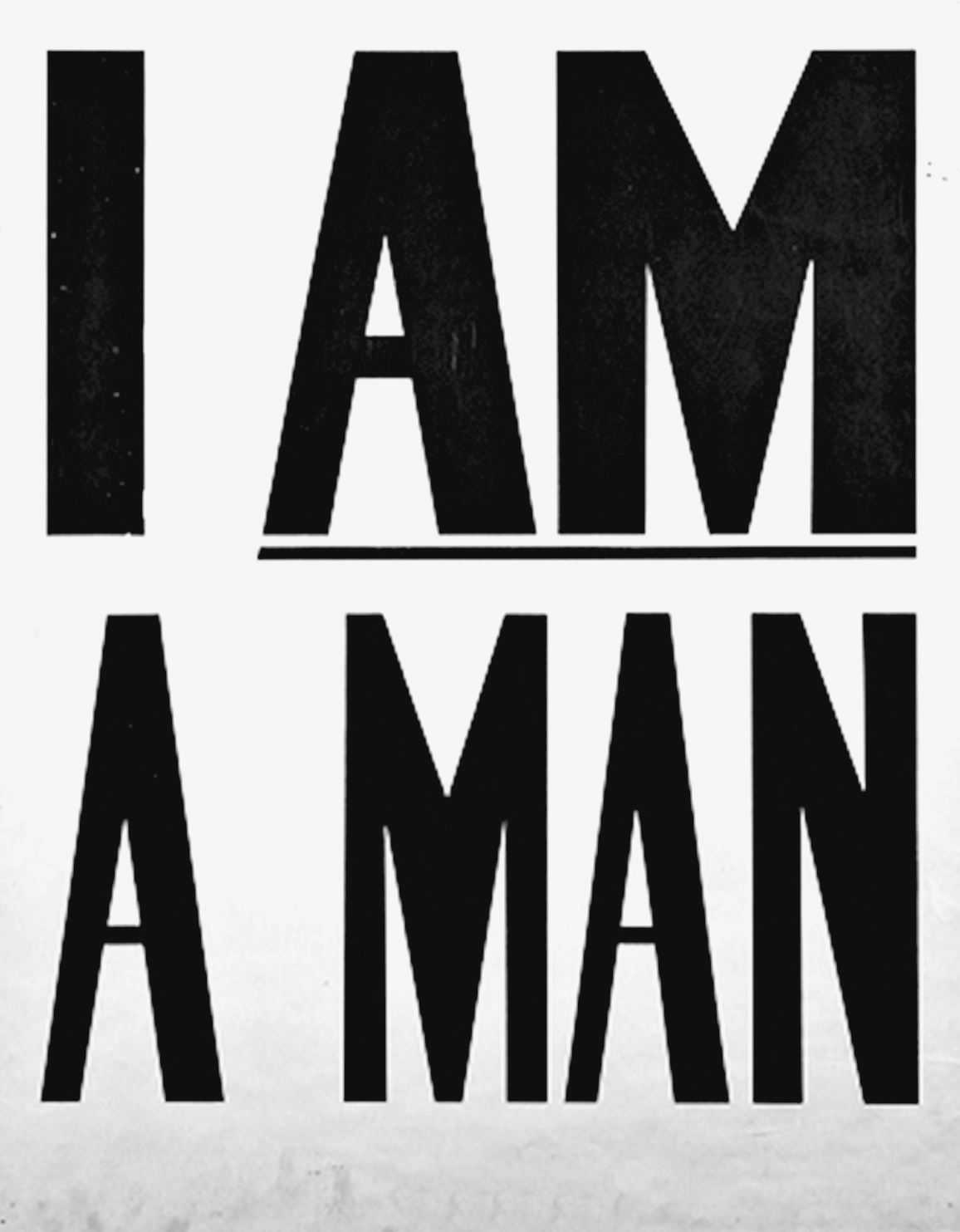

Since 8 a.m., strikers, their families, and community supporters had gathered outside Clayborn Temple. In a festive mood, they intended to show Mayor Henry Loeb the power of a united community. Hundreds of workers carried placards reading, “I Am A Man.” Parents brought children with them. No one expected trouble. But by 10 a.m. police helicopters buzzed annoyingly overhead. Disheveled men trickled in from the area surrounding Beale Street’s pawnshops, bars, and liquor stores. The boycott of downtown businesses had emptied it of shoppers and hurt the work of petty hustlers and thieves, and they resented it.

“There was an element in the crowd that we couldn’t get rid of . . . nobody could do anything with them,” recalled black city councilman Fred Davis. The “white presence wasn’t exactly overwhelming” in the ranks of the marchers either, said one participant. That made the crowd more vulnerable to police attack, as people grew increasingly restless.

Nearby but out of sight, three hundred Memphis police and fifty Shelby County sheriff’s deputies, almost all of them white and many of them natives of the plantation economy, sat or stood somewhere in the boiling sun. They too were on edge. Many of them had been working seven days a week since the strike began. They carried .38-caliber pistols, shotguns, Mace, and billy clubs, and deputies had their own personal weapons. On the South Side, police attacked black Hamilton High School students as they gathered to go to the march. An ambulance took fourteen-year-old Jo Ann Talbert away on a stretcher; it took twenty-three stitches to close her head wound. As 22,000 students boycotted school and many of them went downtown to join the march, rumors spread that police had killed a black female student.

At Clayborn Temple, a contingent of sanitation workers remained well organized and on message with their signs, “I Am A Man.” But young people made their own incendiary signs, or tore the signs prepared for the march from their sticks and brandished the sticks as clubs. Charles Cabbage and other members of the youth group the Invaders stood at the edge of the crowd giving excited and angry speeches to young people. According to their strategy, nonviolent protesters only achieved their demands when the powers that be feared violence if they did not respond. The Invaders wanted to challenge King’s disciplined, nonviolent methods and ramp up tensions through undisciplined street actions. Once the march started, the Invaders would disappear.

Everyone wanted to know, where was Martin Luther King?

At around 11 a.m., after some people had been waiting for three hours, King and Epps arrived in their Lincoln at Linden and Hernando streets. People swarmed around the car and King could barely get out. Once he got out of the car, “pandemonium broke out,” recalled Lawson, as an unruly sea of people tried to get up close to King. Lawson and King started the march, with sanitation workers behind them, but younger people broke through to get right behind them. Photos show King looking happy at times, apprehensive at other times; film footage records King pressed on all sides and carried along by the crowd, his eyes glazed, his head bent to the side, almost asleep on his feet. As the march picked up speed, reporter Kay Pittman Black heard King exclaim that someone should “make the crowds stop pushing. We’re going to be trampled.” Organizers estimated 10,000 to 15,000 people in the march, funneled down narrow old streets and moving toward city hall. NAACP leader Jesse Turner saw trouble ahead; he considered aborting the march, but decided that could in itself precipitate a riot.

As the crowd moved down Hernando to Beale Street, marchers sang “We Shall Overcome” and chanted “Down with Loeb.” But before King and Lawson got to Main Street, they heard windows breaking and shouts of “Burn it down, baby!” Behind them, excited young people and older men with hardened looks climbed through store windows and began to loot. Some men had looted liquor stores even before the march started. King in the past had been the victim of mob attacks, but never had seemed to be leading a mob. Lawson halted the march.

Up ahead at Main Street and Gayoso, police with gas masks, brandishing guns and clubs, formed a line to block the marchers from going toward city hall. Lawson told King he should leave. King protested, “Jim, they’ll say I ran away,” but Rev. Henry Starks and a cordon of men put their arms through his and took King down McCall, a side street. King’s aide Bernard Lee flagged down two black women in a white Pontiac, and a white police officer escorted them out of the area. The officer later claimed disparagingly to a reporter that King’s “only concern was to run and to protect himself.”

Meanwhile, police and sheriff’s deputies waded into the crowd, using clubs, Mace, and tear gas, as a police report later put it, to “restore order.” Children lost their parents, older people who could not run ducked into doorways. T. O. Jones ran for cover, knowing he would be a special target, but lost his two sons in the swirling crowd. Police burst into the Big M restaurant and ordered people eating to leave; when they didn’t readily comply, they beat them and dragged them out. One of the diners, named Kenneth Cox, and a Firestone worker got in Cox’s car and tried to leave, but the police smashed in the windows and Maced and clubbed them both. It took eight stitches to close Cox’s wound. He was one of hundreds beaten bloody by the police, who freely cursed and called people “nigger” while attacking marchers and bystanders indiscriminately.

Officers wearing gas masks and helmets and holding pump shotguns surrounded refugees from the march huddled together at Clayborn Temple, where Lawson had led people. In the adjacent headquarters of the African Methodist Episcopal Minimum Salary, an organization that aimed to raise salary levels for AME ministers, Lawson was on the phone to the chief of police, pleading with him to stop the mayhem. Tear gas wafted in, forcing Lawson to drop the phone and climb out a window. Reporter Black wrote that “inside the A.M.E. building was a horror show.” People were bathing each other’s faces with water, some lay comatose on the floor, and Clayborn Temple’s white pastor Malcolm Blackburn found a man who he feared had a broken back, lying on the trunk of a car in the alley. Police shot tear gas into Clayborn Temple and beat people as they came streaming out.

In a scene all too familiar in many American cities, looting spread like wildfire from downtown to nearby business districts, as people ran off with televisions, alcohol, musical instruments, and guns. At the John Gaston Hospital, frequented by the city’s black and poor population, doctors treated hundreds of people streaming in with lacerations, broken bones and teeth, concussions, buckshot wounds, and suffering from the effects of tear gas. Private ambulances refused to go into the area of police violence and looting, and all city buses stopped running.

White police officer Leslie Dean Jones, at the low-income Fowler Homes project ten blocks south of Beale Street, spotted Larry Payne, a black sixteen-year-old who the officer thought had looted a television set. Jones cornered Payne in a basement doorway and pulled the trigger of his 12-gauge shotgun. The black-owned Tri-State Defender published a picture of Payne lying against the basement stairwell, his eyes and mouth wide open, both hands above his head. A dozen eyewitnesses confirmed they had seen Payne with his hands up, pleading for his life. The Police Department produced a rusty butcher knife that they said belonged to Payne, but they could not lift any fingerprints from it. Five months after Payne’s death, the department made the bizarre claim that the knife and other evidence in the case could not be examined because they had thrown it all away into the Mississippi River. No one could explain why. Officer Jones was not laid off, nor did a grand jury ever indict him.

Instead of King’s nonviolent “dress rehearsal” for the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, the Memphis march left behind a wasteland, according to the press, with “Main Street and historic Beale Street littered with bricks, blood and broken glass.” One pathetic photo showed a picket sign with a photo of King’s face lying with glass all over it in a smashed store window. Governor Buford Ellington declared a state of emergency and mobilized the National Guard. Stores in the South Side went up in flames as tanks and trucks rolled in. For the next several days Memphis was occupied territory in a military state of siege.

Who was to blame? The news media featured photos of officers who got hurt by flying glass and rocks or injured while fighting with people in the crowd. Fire and police director Frank Holloman, J. Edgar Hoover’s former FBI assistant, claimed that black people had taken up “general guerrilla warfare,” and said, “Yes, we have a war in the city of Memphis.” He told reporters, “I think you should realize what the police department did. They used restraint.”

This was Memphis, touted by its leaders as a city of racial moderation. But the violence that day, blamed by the white media on the black community, could more accurately be called a police riot conducted with impunity. Black Memphians suspected that the white media would cover up or rationalize the police violence, and Dr. King would get all the blame. And they were right.

James Lawson, for his part, appealed: “We are now saying to the city, will you please listen? Will you please recognize that in the heart of our city there is massive cruelty and poverty and indignity, and that only if you remove it can we have order.”

* * *

IN MARCH 1968 the FBI responded to the escalating Black Power, New Left, and antiwar movements by stepping up its surveillance and illegal interventions against organizations and individuals. By the time King came to Memphis, the FBI was employing his accountant James Harrison as an informant; monitoring calls to and from King’s close associates; and sending out regular reports slandering King and others in the movement to the president, members of Congress, the military, the police, and friendly news outlets. On March 4 Hoover had directed FBI field offices to do everything they could to “prevent the rise of a black messiah,” and the FBI was sending out fake letters and disinformation to disrupt the Poor People’s Campaign. The FBI had put King on its counterintelligence (COINTELPRO) “agitator index.” Going back to the McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950, the United States actually had funded and designated detention centers and a list of people to be rounded up and put in them during a national emergency—and King was on that list.

Throughout March 1968 a steady drumbeat of hatred confronted King. Most southern news media ridiculed the report of the presidentially appointed commission headed by Ohio Governor Otto Kerner, mandated to investigate the causes of inner-city riots. Issued in early March, the commission’s report supported King’s conclusion that white prejudice, police violence, and institutional racism caused inner-city rebellions. Meanwhile, the political right continued to blame ghetto residents and King. George Wallace, running for president, blamed hippies, New Leftists, and African Americans for America’s turmoil and pledged to run over any protester who lay down in front of his car. When the name of King came up in the media in 1968, it often sat next to a headline on “Communist aggression” during the Tet offensive and the siege of the American military base at Khe Sanh in Vietnam. Many newspapers made it appear that King and a host of subversive allies at home and abroad had the United States under siege. King had joined Jack O’Dell to give a speech honoring Dr. Du Bois at a Freedomways dinner held in New York on February 23, the same day as the first police riot in Memphis. In response, the FBI sent out an anticommunist alert to the media. The Birmingham News followed up on March 7, 1968, with a big front-page headline: “King, Red ex-aide team up again.”

Conflict in the streets of Memphis on March 28 confirmed what most white southerners already thought, and what the FBI had long been preaching. Assistant FBI director William Sullivan, as part of the FBI’s campaign to stop the Poor People’s Campaign (code-named “POCAM”) was in hourly contact with his agents in Memphis. His note to them highlighted the idea that although King “preaches non-violence, violence occurs just about everywhere he goes.” On March 28 and 29, the FBI’s “Racial Intelligence” section sent out “blind memos” to its press contacts around the country promoting this view. The Commercial Appeal wrote, “Dr. King’s pose as a leader of a non-violent movement has been shattered.” Another article was headlined “Chicken a La King,” and an editorial cartoon pictured King shrugging his shoulders and saying, “Who, me?” with Beale Street in tatters behind him. The Jackson, Mississippi, Clarion-Ledger’s columnist Tom Ethridge revealed that “secret FBI records definitely tie Martin Luther King with Communism.” The anticommunist drumbeat that had followed King most of his adult life now got louder. David Lawrence of U.S. News and World Report quoted HUAC, reporting that antiwar demonstrations in April that King planned to participate in “are part of a worldwide movement by the Communists.”

The clamor must have reminded King of the days before President Kennedy’s assassination, when the John Birch Society had agitated in Dallas that Kennedy was part of a communist plot. Indeed, if the southern mass media hated any public figure more than King, it was Robert F. Kennedy. Segregationists viewed him as an insidious interloper representing the northern liberal elite; on March 20, the Montgomery Journal on March 22 ran a cartoon that pictured Kennedy with horns on his head and decried a subversive “Kennedy-King Alliance.”

Opponents of King and Kennedy merged their hatred for the two men. They were right that they had a lot in common: both wanted to bring the poor to Washington, and both would soon be dead at the hands of assassins.

* * *

AFTER THE HORRORS in Memphis, people close to King reported that he was devastated, anxious, and deeply depressed. But in public he carried on with a calm demeanor and discourse. When reporters in Memphis asked him about accusations that he “ran” when “the going got rough,” King told them he left the march because “I have always said that I will not lead a violent demonstration.” But he also reminded them of the conditions of poverty and police violence reflected in the events on March 28. He warned that no one could guarantee peaceful demonstrations unless American society did something about the dire conditions that set off violence in its inner cities. In reality, the breaking of store windows in a confined area of Beale Street only barely amounted to “riot”; police inflicted or set off most of the violence to people that occurred.

Remarkably, after leaving Memphis, King continued on his national campaign. Speaking to a packed crowd at the Washington, D.C., Cathedral on Sunday, March 31, he called on America to wake up to the “human rights revolution” occurring in the world. The next day, in Memphis, 450 people marched again from Clayborn Temple to downtown. Thousands of people filed by Larry Payne’s body as a funeral home prepared him for burial. Daily marches and organizing among the workers and their allies resumed. On April 3, despite strong opposition from his staff, King came back to Memphis. He vowed to lead a mass nonviolent march regardless of a court injunction on behalf of the city that would put him in jail for doing so. Despite violent storms late that night, King at Mason Temple called on people to exercise “dangerous unselfishness” on behalf of the poor. He urged his audience to continue down the dangerous Jericho Road taken by the Good Samaritan despite all fears and difficulties. He electrified his audience with his ringing conclusion, “I may not get there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the Promised Land!”

On March 28, when he could not get to any other place to stay because of the riot spreading through the city, King had stayed at the Rivermont Hotel. With FBI prompting, Memphis newspapers called him a hypocrite for not staying at a black-owned hotel. This time, to avoid such criticism, he stayed at the black-owned Lorraine Motel. He had stayed there so many times that its owners, Walter and Lorraine Bailey, reserved a room for him and did not charge him to stay. They cooked him collard greens and brought food to his room. The newspapers and television news published his room number, 306. The room faced an open-air balcony. It provided no security.

Investigative reporters later discovered that a plainclothes unit of the Military Intelligence Division of the U.S. Army, which had an office in downtown Memphis, roamed the streets and watched King’s every move. The FBI and the Memphis Police Department worked hand in glove to infiltrate the ranks of the strikers and the Invaders, a group that now demanded payments from SCLC in order for them to cooperate with building a nonviolent demonstration. Security forces tracked King’s every move, and several officers watched King’s room in secret from a firehouse across the street from the Lorraine. Police cars circled the area for miles around. Yet no one was assigned to guard King. Higher-ups in the police department had removed several black police officers who had previously considered it their duty to protect King. And because of their record of attacking the movement, white police officers were not particularly welcomed by SCLC.

On April 4, King’s aides and lawyers went into court and Rev. Lawson argued that the city would be better off having King lead a legal march on April 8 than to have him arrested for breaking an injunction against marching, which could set off another upheaval in the streets. The court approved a march to be held on April 8. King and his entourage were in a happy mood, getting ready to go to dinner. As King stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel bantering with his colleagues in the parking lot below, a bullet slammed through his jaw.

Within an hour, Martin Luther King was dead. That night riots began in Memphis, and for the next three days, riots consumed the nation. When hotel co-owner Lorraine Bailey learned King was shot, she had a heart attack, and would die five days later. Coretta Scott King was grief-stricken, but not surprised. “We knew that FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had labeled my husband a public enemy, a threat to the United States of America. How could we not know were living on borrowed moments?” She later wrote, “For most of our married lives, Martin and I knew that one day there would be a scene like this. . . .”

Robert F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy reached out to comfort her and help bring her husband’s body back to Atlanta. Coretta Scott King and her husband’s family had a long haul ahead. King’s brother A. D. would drown in a swimming pool a year later, and on June 30, 1974, a madman would shoot King’s revered mother to death while she was playing “The Lord’s Prayer” on the organ at Ebenezer Church. Daddy King would end up without his sons and his wife, helping to raise Martin and Coretta’s four fatherless children.

Later, people wondered how James Earl Ray, an escapee from federal prison, could go unnoticed when he purchased a Gamemaster rifle powerful enough to bring down a charging bull. The law did not require that he register the weapon or be checked for criminal background. A poor white brought up in a dysfunctional family, Ray could have been a candidate for the Poor People’s Campaign. Instead, in his life of petty and bungled thievery and imprisonment, he chose to follow George Wallace and subscribe to KKK publications. Rumors circulated of a supposed reward for King’s death from an unidentified businessman in St. Louis, the area Ray came from. On the evening of April 3, Ray took a room in a boarding house where the bullet that killed King seemed to have come from across from the Lorraine Motel. After the shooting, on April 4, he fled Memphis.

King’s assassination was one of a string of murders of public officials and movement leaders and grassroots activists throughout the 1960s. Time after time when a hopeful leader appeared, that leader was killed. After King’s murder, the FBI apprehended Ray as he was trying to board a plane from London to the white supremacist republic of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Ray pleaded guilty to King’s murder but later recanted his plea. Because of that guilty plea, the evidence against him was never presented in a trial, leaving unanswered questions about who killed King. A congressional inquiry later cast doubt on who killed King and why. A civil jury in a court hearing, conducted by attorney William Pepper, decided that other people may have killed King but was widely derided for faulty methodology and bias. Ray had every reason to want to kill King, and his alibis seemed like fabrications. But whether Ray or someone else pulled the trigger, Andrew Young later wrote, the issue was not who killed King, but what killed King. And why did it happen? Young thought the answers to those questions went to the heart of a society built on slavery and segregation.

Right-wing and racist hate had plagued King all of his life. He said hardly a day went by that he didn’t get a death threat. As Stokely Carmichael later put it, “Every Klan and Nazi group had a bounty on his head. Martin Luther King was the number one target for every racist with a rifle, shotgun, or stick of dynamite.” Is it any wonder that he had strong premonitions of death when he gave his “Promised Land” speech? His colleague and companion Ralph Abernathy wrote that King had many fears but refused to give in to them. Had he not been a brave man, “none of the rest of us would have followed him and we might still be riding in the back of buses and eating in segregated restaurants.”

While most people today see King as a prophet, many whites reviled him in his time. Strike sympathizers recorded many of the gross jokes they heard in the streets and shops of Memphis after King’s death. A survey of Memphis State University white students in three classes found 20 percent approved of King’s murder, and 19 percent didn’t care one way or another. A reader wrote in a letter to the Commercial Appeal what many white people said on the streets and in their living rooms, that King was “the biggest Communist in the nation.” Others said the problem was black people themselves. “No matter what else there is, you just can’t overlook that black skin,” a neighbor told one Southwestern College professor. Rev. Lawson remarked that hatred of King symbolized white America’s “moral blindness.” He did not think America could really change unless Euro-Americans came to understand King’s message.

After the murder of King on April 4, National Guard troops reoccupied Memphis. Nationwide, riots led to more than 20,000 arrests, at least forty-three deaths and $100 million in damages. The federal government called out some 50,000 troops, responding to riots in perhaps as many as 130 cities. It was the largest use of federal force to suppress domestic rebellion since the Civil War. The 14th Street corridor in Washington, D.C., remained burned out for years to come. In Memphis, amid drawn bayonets, walking past tanks and soldiers in jeeps with their rifles prominently displayed, the sanitation workers marched on.

The Memorial March for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on April 8, 1968, makes its way down Main Street. Mourners include a mixture of civil rights activists, members of the clergy, and union leaders. It included James Lawson, Cornelia Crenshaw, Jerry Wurt, T. O. Jones, May and Walter Reuther, Coretta King and three of her children (not shown).

Marchers in Memphis on April 8 honored King by demanding union rights and an end to racism.

On April 8 people came from all over the nation to hold a completely silent march from Clayborn Temple through downtown Memphis. Hate mail and phone calls threatening death had inundated James Lawson throughout the strike, and in the middle of the night on April 7, someone called to say tell him that when he reached Main Street, “You’ll be cut down.” Lawson, thinking he too would not live much longer, walked at the front of the march, along with Coretta King, union leaders Jerry Wurf of AFSCME and Walter Reuther of UAW, Harry Belafonte—one of King’s strongest supporters—and other King associates.

According to wildly varying estimates, on April 8 in Memphis somewhere between 19,000 and 42,000 people demonstrated their respect for King and their refusal to give in to violence. Even the Invaders helped to provide marshals to maintain nonviolent discipline for the event. Through her composure and her heartfelt statements, Coretta Scott King drove home her husband’s message of nonviolence even unto death. On April 6 she had issued a statement: “The day that Negro people and others in bondage are truly free, on the day want is abolished, on the day wars are no more, on that day I know my husband will rest in a long-deserved peace.” On April 8, at the Memphis demonstration, she declared, “his campaign for the poor must go on.” But she also cried out, “How many men must die before we can really have a free and true and peaceful society? How long will it take?” Yet she still believed that “this nation can be transformed into a society of love, of justice, peace, and brotherhood.”

A domestic worker in the audience named Luella Cook said, “If Mrs. King had cried a single tear, this whole city would have give way.” There had been some fires and destruction right after King’s death, but this nonviolent rally put an end to it. “Memphis was in fact the quietest place in the nation,” AFSCME’s Bill Lucy later recalled. Students from Hamilton High School, where police attacks had set off a frenzied student response on March 28, also attended, among them Alice Wright, granddaughter of a striking sanitation worker, and Ernestine Johnson, who had cried herself to sleep on April 4, and said she felt hopeless until she heard Mrs. King speak. Then, “I got the courage to go on with life and struggle . . . to make something of myself.” Others inclined to violence decided to honor King that day with nonviolence.

April 8 also symbolized the union- and civil-rights coalition King had sought to build. Union members all over the country stopped work and held memorial gatherings. The AFL-CIO sent a check for $20,000 and mailed a letter to member unions that raised thousands of additional dollars to support the strikers. UAW President Walter Reuther brought a $50,000 check for the strike fund to the memorial. The International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) led by Harry Bridges shut down a number of West Coast ports for twenty-four hours, as did unionized black workers in some Mississippi Gulf ports. The cry went up among union- and civil-rights supporters for a national holiday to honor King. Members of the unions King worked with, including District 65 RWDSU, which demanded a King holiday in all of its contracts, 1199 Hospital Workers, which began a major educational campaign around labor and civil rights, and the United Electrical Workers Union (UE), National Education Association and American Federation of Teachers, AFSCME, the United Furniture Workers Union, the Screen Actors Guild, and steel, packinghouse, auto, longshore, rubber workers and many other unionists memorialized King as a labor hero. On April 8 in Memphis, “The town was full of labor people,” said Bill Ross.

On April 9 in Atlanta, between 100,000 and 150,000 people from all walks of life marched through the streets following a mule-drawn wagon honoring King’s struggle to launch the Poor People’s Campaign. The funeral there played the “Drum Major” sermon that King had given at Ebenezer Baptist Church on February 4, exactly two months before his death. He had said that when the time for his funeral came, he wanted people to remember that “Martin Luther King, Jr., tried to give his life serving others. I’d like for somebody to say that day, that Martin Luther King, Jr., tried to love somebody. I want you to say that day, that I tried to be right on the war question. . . . I want you to say that I tried to love and serve humanity.”

* * *

ASTONISHINGLY, TO AFSCME president Jerry Wurf, the Memphis workers continued marching but Mayor Henry Loeb still refused to sign a contract. White and black ministers, over one hundred of them, confronted Loeb the day after King’s death, demanding that he settle the strike. But talking to Loeb, many said, was like talking to a wall. He would seem to listen, but his opinions never changed. National companies started to cancel contracts to hold meetings in Memphis. Cornelia Crenshaw, Dorothy Evans, Tarlese Matthews and others picketed stores and told shoppers to boycott downtown businesses in the biggest shopping days before Easter.

After weeks of contentious debate, on April 4 the U.S. Senate passed the Fair Housing Act banning discrimination in the rental, sale, and financing of housing by race, religion, national origin, or gender. The House of Representatives passed it on April 10, and President Johnson signed it on April 11. King had at last won one of the major demands of the Chicago demonstrations, a national law banning housing discrimination. President Johnson also sent James Reynolds, the U.S. Labor Department’s top negotiator, to Memphis. In his response to the Memphis tragedy, Senator Eastland took the National Rifle Association’s position and blocked a gun registration law that might have prevented the purchase of the gun, or at least readily identified who purchased the gun, that killed King.

Ultimately, the Memphis City Council settled the sanitation workers’ strike without Loeb’s help. The complicated negotiations required private donations to pay the cost of tiny wage increases; provided a memo of agreement, not a contract; and, because of Tennessee’s right-to-work law, workers could not be required to join the union or pay dues. “All we did get was a premise for staying alive,” Wurf later explained. But in the first clause in the contract it signed, the City of Memphis recognized AFSCME Local 1733 as a collective bargaining agent; that word “recognition” was the key to the demand of “I Am a man.” The city also allowed workers to voluntarily have union dues deducted from their paychecks; guaranteed they could not be fired for joining a union or talking about it at work; opened up promotion to higher-paying jobs; set up grievance procedures; and included a nondiscrimination clause—the kind CIO unions had fought for since the 1940s. The workers gained a few cents an hour in wage increases, but of all these provisions, Wurf said, the most important was to make union membership “a basic right in a free society.”

On April 16, at Clayborn Temple, after sixty-five days on strike, the sanitation workers stood up, to a man, and approved the agreement. They whooped, cheered, and cried. Tears streaming down his face, T. O. Jones said, “We have been aggrieved many times, we have lost many things. But we have got the victory.” A general celebration ensued. White AFL-CIO Memphis president Tommy Powell said he hoped black and white workers could now join to elect some decent politicians; Cornelia Crenshaw called for organizing hospital and domestic workers; Rev. Lawson pledged a lasting alliance between civil rights and labor. People joined hands and swayed together, singing “We Shall Overcome,” including the verse, “Black and white together.”

Their movement came out of two tragedies, the loss of Echol Cole and Robert Walker that set off the strike and the death of Dr. King that ended the strike. Taylor Rogers, who became Local 1733 president for twenty years, told me that this struggle was not in vain. King, he said, “went where he was needed, where he could help poor people. . . . He didn’t get all accomplished he wanted accomplished, but I don’t think he died in vain. Because what he came here to do, that was settled.” As King’s mentor Benjamin Mays said on April 9 in Atlanta, King “believed especially that he was sent to champion the cause of the man furthest down. If death had to come, I am sure there was no greater cause to die for than fighting to get a just wage for garbage collectors.”

* * *

IN THE AFTERMATH of King’s death, donations to the Poor People’s Campaign soared. The national AFL-CIO never endorsed the campaign, but King’s close union allies and the UAW invested thousands of dollars in it and members of various other unions participated. On April 27, Coretta Scott King spoke at a mass antiwar rally in New York City, reading from “Ten Commandments on Vietnam,” a note found in her husband’s coat after the assassination. The tenth was “Thou shall not kill.” Mrs. King addressed women especially, saying, “The woman power of this nation can be the power” to make the nation whole by ending racism, poverty, and war. On May 2, 1968, she placed a wreath outside room 306 at the Lorraine Motel, beginning a caravan that would travel down to Marks, Mississippi, and through Alabama and Georgia to Washington, D.C.

Many of the people King had spoken to in February and March would follow a mule-drawn carriage through the South and onward to the nation’s capital. Other caravans started on the West Coast, including Native Americans fresh from fishing-rights struggles in Washington State, and Chicanos demanding land rights in the Southwest. On May 12 Coretta Scott King walked with Ethel Kennedy, the wife of Senator Robert Kennedy, in the front row of a Mother’s Day march of the National Welfare Rights Organization through the streets of D.C. She wrote, “We highlighted the plight of poor women and children . . . from rural Appalachia to the urban ghettos,” demonstrating women’s power in the fight for “decent medical care,” a life without hunger, and against welfare “reforms” that made life harder on recipients and their children.

The Poor People’s Campaign brought together many of the people King had struggled to organize from various parts of the country. Participants included unionists, religious people, students, and others, and even armed self-defense advocates like Charles Cabbage of the Invaders in Memphis and Bobby Seale of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. Most important, the poor themselves turned out and established an encampment of 2,500 people on the national mall, and called it “Resurrection City.” Mexican Americans, Native Americans, poor whites, Puerto Ricans, and African Americans all came to Washington. Freedom singers Jimmy Collier and Brother Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick, as well as a Poor People’s University created a sense of collective and interracial purpose. Although the campaign did not produce new legislation or the attention to poverty King desired, according to historian Gordon Mantler, “Its organizers and participants made great strides in producing, at least at times, a unified multiracial voice for the poor.”

Police in Detroit, cheered on by Donald Lobsinger and his Breakthrough right-wing activists, had beaten up PPC travelers when they came through. Police also harassed people in Marks before and after the campaign. On June 5, Robert Kennedy won the California primary, virtually assuring that he would be the Democratic Party’s next presidential candidate. At the end of a celebration that night, a Palestinian Arab nationalist named Sirhan Bishara Sirhan, seeking revenge for Kennedy’s support for Israel’s military actions in the Mideast, shot him with a handgun and Kennedy died on June 6. UAW organizer Paul Schrade was among the wounded, and former SNCC chairman John Lewis was in a room next to where Kennedy was shot. He fell to the floor sobbing, having lost his two model leaders, King and Kennedy. Followers of both men would line the railroad tracks as a train returned Kennedy’s body to the nation’s capital.

The Poor People’s Campaign carried on. Walter Reuther came to speak at a mass interracial rally of tens of thousands on June 19, 1968, called Solidarity Day, where Coretta Scott King called on participants to continue to teach and organize around the power of love and nonviolence. Despite this high point, however, devastating rains beset the shantytown called Resurrection City in honor of King; delegations to Congress demanding action for poor people got little support. Police in July demolished the poor people’s encampment, and forced its residents to leave. Two years later, on May 7, 1970, Walter Reuther and his wife May died in a plane crash. Many of the people who supported King’s labor–civil rights agenda passed. The media and most historians cast the Poor People’s Campaign as a failure.

Demonstrators from across the country converge on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., during the Poor People’s Campaign on June 19, 1968.

Coretta Scott King supported Local 282 of the United Furniture Workers Union, which continued to organize in Memphis, as workers remembered King on April 4.

However, in that campaign people learned skills and crossed cultural boundaries, and many of them began a journey for economic justice that they continued for the rest of their lives. King had told his staff when they worried about the campaign’s possible effectiveness that failure consists of people not trying to bring about a change; failure consists of good people remaining silent in the face of injustice. From Montgomery to Albany, St. Augustine to Atlanta, Birmingham to Selma and Chicago, the March Against Fear in Mississippi, the Poor People’s Campaign, and the Memphis sanitation strike, every campaign Martin Luther King worked on involved both failures and successes. King, Lawson, and others understood that the struggle doesn’t stop. Put simply in the civil rights anthem, “Freedom Is a Constant Struggle.”

Yet, in his last days, King had feared that racial prejudice and the legacy of slavery remained America’s greatest obstacles to becoming a functioning democracy that would benefit all its people. In an article published posthumously in Look magazine on April 16, 1968, King wrote that he even feared that resurgent racism could lead to a form of American fascism. In a series of Christmas sermons aired on the Canadian Broadcasting system in 1967, he had explained, “There is such a thing as being too late.” And he warned, “Disinherited people all over the world are bleeding to death from deep social and economic wounds. They need brigades of ambulance drivers who will have to ignore the red lights of the present system until the emergency is solved.” In this broadcast, King said that pursuing the American Dream required a renewed commitment to economic justice for both the unemployed and the working poor. “It is murder, psychologically, to deprive a man of a job or an income. . . . You are in a real way depriving him of life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness, denying in his case the very creed of his society. Now millions of people are being strangled in that way. The problem is international in scope. And it is getting worse. . . .”

People in Memphis remember King every year on April 4.

King dreamed of much more than obtaining civil rights and voting rights. In his fight for a phase two of the movement, for economic justice, he remained uncertain whether the deeper tentacles of racism would be uprooted. And he feared time was not on his side. AFSCME’s William Lucy told me, “Dr. King really highlighted the great contradiction. . . . If you relieve the civil rights shackles or barriers, that does not necessarily guarantee that your economic situation will change. There is something wrong with the social structure. There is something wrong with the economic structure.”

* * *

EVEN AS WE fight to stop regression and rollback of fundamental rights in our own times, the achievements of phase one of the freedom struggle cannot be fully undone. American apartheid is gone; there is no putting it back. Memphis provides one example of that. Many people there as elsewhere carried on “the long civil rights movement” into the 1970s and beyond. In Memphis in 1974, Harold Ford, the first black congressman in the Deep South since Reconstruction, replaced the reactionary congressman Dan Kuykendal, who had excoriated King as a troublemaker during the Memphis strike. After many years of electoral struggle by black voters and a few white allies, in 1991 Memphians elected Willie Herrenton as their first black mayor; he continued in office for sixteen years with good and bad results. African Americans and Latinos and women joined a unionized police force and it became less like an occupying army; interracial friendships and sexual relations became acceptable to many. AFSCME, elected officials, and civic activists turned the decrepit Lorraine Motel into the National Civil Rights Museum. Along with Memphis music and civil rights tourism, a widespread and multiracial sense of civic engagement keeps the “spirit of Memphis” alive. As economic historian Gavin Wright documented in Sharing the Prize, by taking steps toward integrating workplaces, education, skilled jobs, and political office holding, the civil rights revolution to a significant degree raised incomes and benefited both blacks and whites. With the election of America’s first black president, Barack Obama, in 2008, some thought phase one of the freedom movement for legal and voting rights had triumphed. Even as efforts have accelerated to turn back voting and civil rights, it will be hard for anyone to fully turn back the results of phase one of the freedom movement.

However, King’s demand for a phase two of the freedom movement, for economic justice, stalled. From the 1980s onward, even while incomes of the top one percent skyrocketed the loss of union jobs and wages undermined the strongest sector of both the black and white middle class—unionized workers. In Memphis, the unionized Firestone, International Harvester, and RCA plants all closed. Union density plummeted; wages cratered; working families frayed or collapsed; drug use, family violence, criminalization of the poor, and mass incarceration escalated. As the sociologist William Julius Wilson wrote in a study of Chicago in the 1980s, this is what happens “when work disappears.” Retired Memphis union member Evelyn Bates told me, “This is pitiful how you can go by all of these factories, and the windows are all broke out. The building just sitting there, just going to waste. No jobs. Nothing to look forward to” for the younger generation. Deindustrialization especially damaged working families dependent on laboring jobs. Black and Latino incomes on average got stuck at only about 60 percent of those of whites.

Memphis in some ways is a poster child for a much greater degree of civic engagement and spirit since the 1960s. But it also serves as an example of the hit taken by the interracial American working class. The near-meltdown of the American economy in 2007–2008, spiraling health insurance costs, the collapsing housing market, and the loss of good jobs hit black Memphis especially hard. This city, now of 600,000, has one of the highest poverty and infant and maternal mortality rates of any city of its size. The issue of labor and race remains at the heart of a continuing crisis for many black workers, and for white workers as well. And across the nation, employer and politician demands for low wages, low taxes on the wealthy, and no unions have returned, as the low-wage economic model of the South has gone national. In 2010, the Republican attack against public employee unions and wages from Governor Scott Walker in Wisconsin ramified across the country, with right-to-work laws popping up in previous northern union strongholds like Wisconsin and Michigan. As taxes and incomes and federal funding declined, “cost cutting” became a strategy everywhere. The City of Memphis and other governments sought to freeze wages, cut health benefits, mechanize jobs and contract out work to private companies. A return to cheap wages and privatization threatens the very existence of AFSCME Local 1733 and of public-employee unionism. “If they can dig up the root, they can topple that tree,” said long-time union activist Gail Tyree.

Private sector unions, now representing less than ten percent of the American workforce, also remain under attack. In 2013, the Kellogg Company, a profitable national megacorporation, locked out its union workers in Memphis, put nonunion workers in their place, and demanded a two-tiered wage system that would impoverish the next generation. Union members picketed for sixteen months, and lost cars, homes, and health care. Families broke up. The Kellogg workers ultimately won their jobs back through appeals to the courts and the National Labor Relations Board, but the company put a second tier of lower-wage workers in place. In Memphis as elsewhere, when people at the local level tried to raise wages and taxes to support social policies and help the community, Republican state legislatures passed laws taking away local power to enact these policies. Integrated schools exist, but under such precarious political and economic conditions that many flee to private schools. And climate change and ferocious weather have put infrastructure and housing at risk for people of all ethnicities everywhere.

Perhaps a third of African Americans in Memphis count themselves as “middle class,” but two-thirds are not. Most African Americans are only a few paychecks away from falling, like about another third of blacks, into poverty. Those with jobs are no longer primarily unskilled laborers and domestic workers but employed in service, education, distribution, and health economies, where the great majority still lack union rights and control over their economic future. Although higher wages for working-class people clearly benefit a consumer-based economy, the low-wage, antiunion model is back in style, not only in Memphis but nearly everywhere. And government for the benefit of the rich and powerful to the detriment of the rest for us has returned with a vengeance.

* * *

ON APRIL 8, 1968, when Coretta Scott King and thousands of others in Memphis had honored King in a silent, nonviolent march, many carried picket signs reading, “Honor King: End Racism,” and “Union Justice Now.” Mrs. King continued supporting worker-organizing in numerous campaigns, as an honorary member of 1199 Hospital Workers and AFSCME. She led a campaign to obtain a national holiday in honor of Dr. King and the things he stood for. When President Ronald Reagan signed it into law on November 2, 1983, Mrs. King commented that it was the first holiday to honor “an American who gave his life in a labor struggle.” She continued throughout her life to support union rights, to speak loudly against war, and to embrace lesbian, gay, and transgender rights. James Lawson too carried on the nonviolent organizing tradition, including among Latino immigrants and service economy workers in Los Angeles after he moved there in 1974 to pastor Holman United Methodist Church. Nonviolence, he continued to teach, remains the most potent weapon for creating positive social change.

More than fifty years since his death, King’s message of agape love, or love for all, lives on. In his last book, Dr. King pointed out that all of us live in a “world house,” and that what affects one of us directly affects us all indirectly. While most of us think that “self preservation is the first law of life,” King objected that, actually, “other-preservation is the first law of life.” Ending racism, poverty and war in a global economy and a global climate requires everyone to develop an “overriding loyalty to mankind as a whole.” Humankind, he wrote, has “a last chance to choose between chaos and community,” and to choose love over hate.

During thirteen years of struggle, he preached a reordering of values and a strategy for change that does not inflict harm. In his fight for equal rights and economic justice, King left behind a theory and a practice of nonviolence available to all. Almost anyone can express his or her beliefs by writing a letter and speaking out. One does not need a PhD or a minister’s eloquence to go out on the picket line, to go to jail for a just cause, or to organize people for positive change. King emphasized that “everyone can be great, because everyone can serve.”

From Memphis to Seattle and beyond, people still march and unionists and organizers everywhere still draw inspiration by remembering King as a hero to the American working class, the poor, and the oppressed. King stressed that “either we go up together or we go down together.” As he told the AFL-CIO in 1961, the key ideal for humanity is solidarity, “a dream of a nation where all our gifts and resources are held not for ourselves alone but as instruments of service for the rest of humanity.” Are we moving in that direction? Many are still asking, as King did in his last year, “Where do we go from here?”