The fall from a static conceptual foundation of objectivity, uncovers a new dynamic relationship to wholeness. Goethe becomes our guide in translating into practical terms the consequence of this surrender. Wholeness is responsible for the dynamic articulation of the concepts, which in turn are the mediators of the unity of form, as expression of wholeness. Goethe’s method actively researches the basic conceptual foundation, to allow the concepts thus found to reveal the form’s meaning. Here the mediating role of concepts is applied to Goethe’s study of plants, the bacteria colonisation process, the slime mould, the self-relation of the cell, quantum coherence of photosynthesis, the bee dance: they all illustrate the transformation of chance into a unified arrival.

One as expression

For the Ancient Greeks, (see the quotes of Aristotle and Domninus in the last chapter), the one was the unit before quantity, the one allowed something to be known as a ‘number of…’ It was only the uniqueness of the existence of one stone that gave any meaning at all to two stones, three stones, four stones… Number, for the Greeks, had no abstract existence, except as it applied to real things. In other words, concept and number were accessed through a specific experience of encountering the world as one.

So for instance a temple had measurements for its columns’ height, breadth and depth, but this was only an example of the divine proportion that characterised the unity of such buildings. Temples, having this relation to a particular unity out in the world, were quantified in size as a secondary exercise. Similarly Pythagoras understood the notion of musical harmonies, without any attempt at measuring sounds as wave frequencies. What he understood was the proportions between notes that sounded harmoniously. So music had the quality of evoking the unity that was already primal in the very notion of music before any piece was played. Or the arrangements of the planets in the solar system played the music of the spheres, each planetary orbit mathematically constructed about perfect geometrical figures. The concepts mediated the experience of the aesthetic unity of the world.

This was the Greek understanding of one as the inherent quality of things from which concept and number followed.

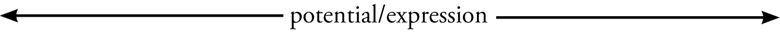

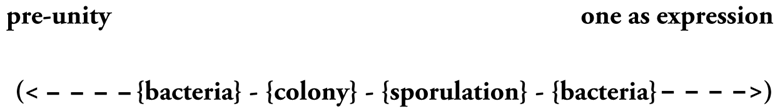

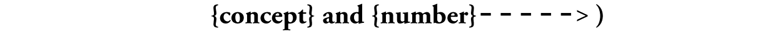

We can symbolise this as follows:

The symbol >) shows the limit where the process of finite rendition actively meets with the unity. The limit to the process of finiteness is the expression of one in the world. The {} brackets signify the definition of concept and number.

The Renaissance drew into the creativity of the mind, the very unity that had existed before in the world. The search of the natural philosophers was to seek the unity that existed behind number or concepts. Numbers became not only more real than the things they represented, but it was through number that the real unity of the world could be found.

For instance ‘general analytics’ attempted to find whether there was an order of reality behind that which we immediately see. Vieta, a key proponent of this school, called this a finding of findings. Can we find behind numbers themselves, an order that applies regardless of the entity we are addressing? In algebra, the substitution of general elements of ‘x’ or ‘y’ for things took away all ties with the one that was in the world. The mathematics of number said how things in general behaved.

Descartes took this type of thinking to its extreme. He suggested the only unity was that which could be reached through the mathematics of number. He completely denied any reality approached through the senses. He discounted the unity which was already extant. He put in its place the general quality behind mathematics of number as the true source of order.

Pre-unity

The realisation of Descartes’ dream was quantum theory. Quantum theory finds a way of arriving at the significance of concepts through the mathematics. The concepts that serve to substantiate the act of measurement are given an entirely theoretical relevance. The physics of concepts actively creates the texture of the world according to how happening is observed or measured. The concepts are now entirely abstract elements to do with observation that allow the act of seeing principally to be effective. The concepts are taken as the fixed basis of the effectiveness of the interaction of observer with observed.

Thus Greek thought is entirely turned on its head. The concepts in Greece were given by the aesthetic relation of harmony, proportion, ratio, to the unity in the world. Now the unity of the world is entirely in the mathematics that predicates all that can ever be known about reality as it is revealed by measurement. The concepts are simply the neutral, mental representations that order the seeing of the world into a structure.

Thus the limit to finite existence is now provided behind {concept} and {number}! The ability of mathematics to shed the skin of the finite and symbolise the virtual realm of possibilities is called upon each time there is a measurement, to determine how the finite world of matter works.

Concepts and numbers are derived from a pre-wave of existence that gives the basis of any finite account of the world (through the principal act of measurement). And now the virtual world seems predicated on nothing but a binary system of 0 and 1!

All value has been removed, for the game of concepts and number that we play, while defining us, is totally lost to our impaired sensibility. Only a mathematician is able to appreciate the chances in existence to which all phenomena are ultimately reduced.

A complete about-turn had happened from the Greek externalisation to the western internalisation of unity.

Goethe

It is to Johannn Wolfgang von Goethe that we need to look, not a scientist by training at all, for how to use concepts dynamically.

The world’s possibility is to be found exclusively neither in an aesthetic address of the unity of existence as the Greeks believed, nor in the intellectual abstraction of the generic law, as in science.

The polarity of possibilities between emptiness and fullness establishes the paradoxical foundation giving logical significance in how and what we see. Concepts in this approach are the mediating influence through the abstract potential of emptiness (pre-unity) into the expressed realisation of fullness (one as expression).

The concepts and quantifications of their values, instead of being the end point, are the finite means of development that translate emptiness into the unity of the one as expression.

The parts are ‘passive/active’ ‘holding/transformative’ qualities between the form as whole and the development as dynamic. The parts each have the quality of the whole in them. The parts are not distinct elements of a passive system. The parts actively lead through their individual statement into a greater whole. So Goethe was able to understand the parts as the transformative progress through which the whole form arises.

The part is neither founded on an innate unity as in Ancient Greece, nor is it a virtual attribute of the dynamic mathematics, as in quantum theory. The parts dynamically mediate the whole. The pursuit of the meaning encountered through the paradox of a part that is also a statement of the whole may be illustrated in the biology of the plant.

Metamorphosis of plants

In the classical view of science, the various static elements in the chemical construction of the cell are activated by conditions in spring to gradually transform the elements step by step from seed into the different stage of happening that by autumn has played out the whole life-cycle in regenerating the seed. The make-up of the plant can be distilled to its static elements, for the happening (time) is something treated as quite separate.

In Goethe’s process, all the aspects of the parts, the joining dynamic and the expressed whole, are all disclosed in the process of engagement. One does not need to apply concepts as a theory, the concepts dynamically mediate the what? how? and who? of the whole process, illumined as it were from within.

Goethe identifies the organs of the plant as both the physical parts but also the dynamic elements of transformation. His book, the Metamorphosis of Plants, begins:

Researchers have been generally aware for some time that there is a hidden relationship among various external parts of the plant which develop one after the other and, as it were, one out of the other (e.g. leaves, sepals, petals, stamens). The process by which one and the same organ appears in a variety of forms has been called the metamorphosis of plants. (Goethe, p. 115)

Form is innate to existence itself, form is not simply put there by the projection of a theory.

Goethe spoke of the particular individual plant as being a ‘conversation’ between the living organism and its environment. This metaphor draws our attention to the plant’s active contribution to the form which takes in specific conditions, emphasising the fact that the individual expression of the plant which we see is the outcome of the active response of the organism to the ‘challenge’ posed to it by the environment. (Bortoft 2012, p. 78)

The finite expressing of the plant in its frame is totally dynamic to its setting. As Goethe remarked when travelling through the Alps, his native Weimar plants had adapted, with subtle variations, into the counterparts found in the mountain meadows.

In being ‘plant’, freedom jumps over all finite considerations of what fits where, and so on, and understands each organ as a perfect finiteness of means. As the whole is experienced, so the organs present themselves as pure function. They are not functions of something, they simply are the finiteness which allows the experience of unity in the whole identity. The understanding Goethe draws from the plant totally agrees with modern genetic discoveries. Goethe views the stages of plant development (leaf, sepal, petal, stamen and carpel) as transformations of a basic internal freedom that is exercised in different circumstances to realise the plant differently. Modern genetics now corroborates this.

Theissen and Saedler writing in Nature confirm the functions that Goethe understood intuitively:

Goethe was right when he proposed that flowers are modified leaves. It seems that four genes involved in plant development must be expressed. According to this model, the identity of the different floral organs — sepals, petals, stamens and carpels — is determined by four combinations of floral homeotic proteins known as MADS-box proteins.

The protein quartets, which are transcription factors, may operate by binding to the promoter regions of target genes, which they activate or repress as appropriate for the development of the different floral organs. (Theissen & Saedler 2001)

The identity of the four organs, as Goethe intuits, is not externally programmed but the result of an internal freedom, responding to context.

The puzzling thing is, as one professor of genetics put it to me, how Goethe could have got it so right over two hundred years ago without the resources of modern genetics. The answer is that he did it by learning ‘to think like a plant lives’ through the practice of active seeing. (Bortoft 2012, p. 62)

The leaf sequence orders the various organs of development as they appear in the life cycle of the plant. The framing of the whole nature of the plant is recreated by following the temporal sequence of the leaves in the cycle of their appearing as in Figure 15.

Figure 15. Leaf-form sequence of sow thistle, (Bockemühl, p. 5).

When one follows the cycle forward in time, then it seems as if the whole nature of the plant is allowed for by the development of the partial stages. One gets an impression of a development working to restore unity through the subsequent choices from the first breaking of symmetry in the original leaf. This is the Light in Time movement, where the happenings of time determine the stage of realisation.

On the other hand, one can follow the cycle differently and go anticlockwise from the produced seed to the first leaf and receive the impression that the coherent unity, at the completion of the process, was in fact the originator of the dividing of wholeness that happened at the beginning. In this way of seeing, everything that happens in the living journey of the plant exhibits the character of the finished journey. If one practises this with the leaf sequence, one indeed experiences the whole, telling its story back on itself. One feels then the black eye of the poisonous plant, or the smile of a daisy, as if these characteristics were the object of the growth, now found in the world. One meets with the character of the plant that becomes a subject retelling its existence through a certain cycle of nature. This is the Time in Light movement.

The freedom of expression in the parts is open for the imagination to envision the whole that coherently signifies each of the parts. The form of the various leaves, up to the flower organs, has an ambiguity or freedom, that allows for a whole to signify all the parts relatedly. This is the nub of what Goethe means by pre-unity and one as expression. These unities are not there before the plant journeys into being. The whole signifies the parts dynamically to relate them together as aspects of a single meaning.

In following the round of the leaf sequence, the whole appears as inevitable. One finds the character of wholeness, either by going forward into the actual physical story by which the whole arose out of the parts; or backwards into the way a unity of self-generating potential preceded the parts. The parts as a way to unity may tell the whole in two ways:

- as an actual physical occurrence through the developmental stages of leaf, sepal, petal, and so on;

- as enfolding into the parts, a nascent unity from which everything develops. The pre-unity of potential is not abstracted before the parts, as a mathematical theory may claim, but is imaginistically envisioned as the unity that holds the parts related in a single meaning.

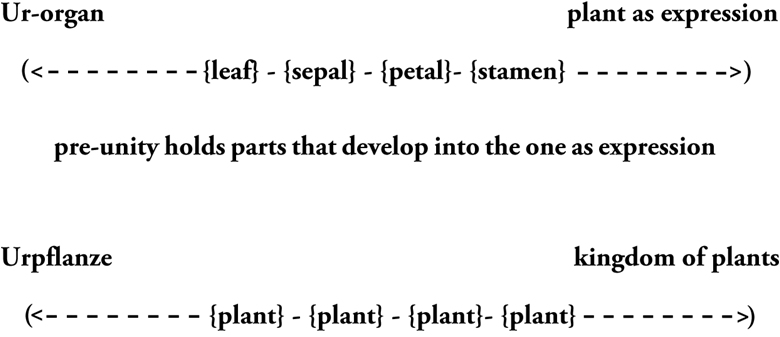

What Goethe is doing is not trying to abstract the plant from its context, but embed the plant into a life process, as the dynamic source of being. Goethe seeks the quality behind the various forms of the plant.

Here we would obviously need a general term to describe this organ [ur-organ] which metamorphosed such a variety of forms, a term descriptive of the standard against which to compare the various manifestations of its form. For the present, however, we must be satisfied with learning to relate these manifestations, both forward and backward. Thus we can say that a stamen is a contracted petal, or, with equal justification, that a petal is a stamen in a state of expansion; that a sepal is a contracted stem leaf with a certain degree of refinement. (Goethe, p. 120)

Goethe then went further into seeing that in studying the difference between all plants, one could allow all these partial forms to suggest the unity that related all these variations into the coherence of the family of ‘plant’. Note that Goethe does not pursue this goal intellectually. Instead he allows the imagination to see the necessary unity of which all plants are an expression.

A challenge hovered in my mind at the time in the sensuous form of a supersensuous plant archetype [Urpflanze]. I traced the variations of all forms as I came upon them. What passionate activity is stirred within our minds, what enthusiasm we feel, when we glimpse in advance and in its totality something which is later to emerge in greater and greater detail in the manner suggested by earlier development. (Goethe, in Mueller, p. 162)

The abstract unity is not arrived at by Goethe as something which reason has conquered as a map of the territory of existence; the abstract unity is touched by the fertile imagination as the backward discovery of origination. The movement to the source knows the journey backward through the manifest forms, to the spring of origination in which the transformative passage to expression is couched.

Method

The Goethean methodology unties the rational, the imaginative, the intuitive and the aesthetic aspects of seeing, into a collective encounter with the whole nature from which all these partial aspects of perception arise. The seeing is not limited to any one partial aspect of human perceiving, say the scientific valued over the artistic or the aesthetic over the factual. Nor does the methodology of Goethe prescribe an instruction for how to blend these different ways of seeing together. Instead the whole process gives coherent meaning to the gleanings from all these different ways of seeing. The method sees into the meaning that is the origin of everything that is observed.

A freedom in each aspect does not close the seeing about one particular interpretation of what is there. Instead the openness of the inquiry allows the quality of meaning to signify the relation between all the aspects of seeing in which one was engaged.

Goethean seeing begins very much like modern science, by looking at the plant or the tree and drawing it and noticing and recording, very neutrally, what is there. For instance, looking at a chestnut tree in spring, one observes the way last year’s buds unfold this year’s growth. The buds shoot forth into new leafing branches. Some buds, instead of extending outwards, develop into flowers. What one at first thinks of as quite mechanical, becomes in looking, quite magical. For instance it is very hard, in looking at the closed winter buds, to imagine the growth of spring that is to occur through them.

The next stage is to fill one’s imagination with this process of development from the bud through leaf and flower. Instead of imagining what is there in terms of one’s own concepts, one sees into the quality of gesture that the chestnut realises.

So the first question one asks is, ‘What? What is there?’ The second question one asks is, ‘How? How is that tree being?’ One finds a sequence of steps in which the plant or the tree develops. Even though one has represented a snapshot by drawing exactly what’s there, the snapshot isn’t the thing itself. What one wants is to find that film, that moving series of snapshots, which is the ‘How?’ of ‘How does that whole embody itself through the parts?’ One tries to get various perspectives. The first question ‘What?’ gave a single perspective or snapshot, but one tries to build up a series of snapshots, to make a film. One might say, ‘Here’s a huge chestnut tree. But now I’m going to look at a conker seed. And then I’m going to look at a little tree, like this, and then a slightly bigger tree.’ One tries to form many snapshots, because one wants to experience this dynamic quality of the tree.

The last stage of the process, called Seeing in Beholding, is asking the question ‘Who are you?’ Here’s an example: one might be busy trying to understand something, and one thinks, ‘Well how did this fit with this, and how did that fit with that?’ And then suddenly one sees the whole journey. Then one really knows the whole, because one can see how it developed. One lets one’s imagination go with all these stages of the journey. And one tries to let something fill in the gaps. So one has all these stages that one has looked at or seen, all these different perspectives and one lets the film run through one’s imagination. Suddenly then the elements observed in stage 1, the happening in the film of snapshots in stage 2 and the seeing of stage 3 are part of a single unique unfolding that is showing itself. And that tells how the whole quality of the plant lives in those parts, those snapshots.

One is travelling in one’s imagination the opposite way to the plant’s motion of expression. One is returning to the pre-material unity that precedes the distinguishing of concepts. One allows this journey of parts to the pre-material unity to distinguish itself in one’s imagination, by a movement experienced as putting together the various conceived parts.

One allows the snapshots of existence to form in one’s imagination and the internal dynamic to identify itself. As with the leaf sequence, one feels the whole that lives by and through the parts.

The concepts are not understood statically, but dynamically as they point to a meaning through them.

Re-membering

Goethe understood that in wholeness, all of time was contained within itself, so that the process of looking at a plant contained within it the secret of how the plant became itself. One had to offer to time a question so that the meaning revealed to the seeking was one with the meaning in the world of the plant. In the process, the nature of the story that is told becomes one with a meaning that needs expression in the world. By opening up to a connection of science with spirit, physics readmits an active living quality, seeking elucidation. This is as with memory, that we do not store old events somewhere in our brain, but we allow that an openness overlays a current questioning with the past experience. The basis of Goethe’s method is that we have to actively establish this bridge of seeking through darkness, so that the light that is the plant’s active meaning can visit itself upon our questioning.

I am drawn back to Eddington’s coordinate system that he used in 1924 to penetrate the black hole phenomenon. One could look into the interior of the black hole through the fate of an in-falling or out-going photon of light. But this made no sense to Eddington, as it appeared to dissolve the ability of the scientist to abstractly conceptualise what was happening. In Goethe’s method, that in-falling or out-going perspective of light is the patience to surrender one’s participation until receiving the illumination of meaning. The phenomenon is written into the attitude of time, as the dynamic receptacle of light’s showing of meaning.

What troubled Eddington was the puzzle that a certain type of dynamic observation was required to give conceptual meaning to the objectivity of what was there. But Goethe (of whom Einstein was a great advocate) understood practically that to apprehend the process of origination, one had to make oneself vulnerable in time. As light gives structure to relativity, so light is part of the reality of the way the world described by relativity communicates its meaning. Only when our perception is up to speed of light, as participant in the revelation of meaning, does the dynamic instance of relativity tell us its deepest secret.

This changes the very nature of our perception. Instead of seeing through a map that our mind has synthetically constructed, our mind is more an instrument that tunes in to the fundamental need of existence. Perception is more of an activity, a ‘remembering’, that recalls the originating process of the organism, as a living revelation of existence.

This nuance of relating was also brought out by Goethe’s very public disagreement with the teachings of Newton on light. For Newton, light was just another material thing, and the colours were the mechanical parts on which such a description was founded. But Goethe interpreted the world as a dynamic process, in which colour was the boundary of interaction between dark and light. For Goethe, one had to know the living quality of light, as a received revelation, to then give place to colour as a concept of existence. Goethe’s world was alive with the creativity of the artist and the communication of meaning. There was no separation in Goethe between the practice of the artist to depict a meaning, and giving to light a place as generator of scientific order.

The paradoxes in different ways of conceiving the world come together in the meaning of ‘seeing’. The concepts do not appear to us statically as either this or that. The remembering, the seeing, the concepts, the unity, are all one. Remembering and foresight are both there in the phenomena. We have the insight into the abstract origin of everything that has been as a remembering, at the same time as we have the foresight of the whole unity, of what the development can become. Everything is woven through each other until the unity places everything in fulfilling relation.

The confusion in the western scientific mind is that having understood the way through concepts back to the abstract unity, it imagines the concepts are purely a mental construct (or else the structure of what is there). In Goethe’s approach the concepts are not static elements the mind holds as the intellectual key to reality. The very foundation of our understanding of the world abandons the finite, as a statement in itself. Science is now a speaking of a journey, where the arrival at whole meaning, transcends but also determines the capacity of space/time description.

Genetic meaning

A huge amount of evidence on genetic involvement has been drawn from biological investigation. It was originally assumed that genetics would provide a passive fingerprint of how randomly coded molecular sequences had encapsulated certain fundamental instructions for the build-up of the cell. The goal of biology was simply to unravel which sequences applied to which behaviours, allowing us to correct imperfections that could be discovered in certain individuals. Indeed certain diseases have been identified as resulting from mutations in the copying of the gene through inheritance.

However the overwhelming impression is that the genes are involved in the most intricate of dances, where hundreds of genes are able to produce proteins that activate or repress other genes in a dynamic of huge complexity. The idea that this dance is genetically pre-programmed diverges from the evidence.

Even silencing various key genes can often result in a totally different genetic pathway being created to realise a vital behavioural action. The genes, the proteins and the cells are seen to be dancing a tension between potential and expression, responding in their mediation to channel the potential of something actively at play into the form of that which is expressed in its own autonomous identity. The dance of genes, proteins and cells, exactly mediates a process of unity resolving itself into form. The complexity of interactions at every level is the process of figuring out how unnamed possibility constructs a frame for its own expression.

Collective expression

Ben Jacob illustrates the individual actions that live a simultaneously coherent unity in the case of bacteria colonisation.

Bacteria were the first life form on earth and though able to exist independently, they form colonies of 109–1012 bacteria. What again is at the very heart of these activities, is the synchronisation of temporal activity so billions of bacteria can act with uniform behaviour. It is the trigger of environmental threat that sets off bacteria into this collective form. (Consider organising twenty humans around a table to agree on something!)

Ben Jacob summarises this universal organisation:

We are referring to a sense-based generation of meaning that occurs at all levels of an organism’s hierarchy of function. Meaning requires on-going information processing, self-organization and contextual alteration by each constituent of the biotic system at all levels. The macro-scale selects between the possible lower scale organizations that are in an entangled state of different options. (Ben Jacob et al., 2006, p. 518)

The last phrase ‘entangled state of different options’ might be translated in non-physics language as ‘woven into their collective potential for meaning.’

The colony identifies itself through a process of discovering the single meaning that establishes the whole as the element of existence beyond the individual membership. It is this organisation alone that lets the individual bacteria survive. The future communicates the single option of coherent assembly that enables survival.

Ben Jacob then draws the parallel with this type of meaning-making with quantum theory in physics.

Metaphorically, the above picture is similar to the notion of quantum mechanical collapse of a superposition caused by measurement. There are two fundamental differences however in the selection from an entangled state of options: 1)… In the organism’s decision-making (selection of an option) an external stimuli or received information initiates the selection of an internal specific option. 2) Both the external information about the stimuli and the selection process itself are stored and can generate an effect on an array of new options and consequent selection processes. Therefore the unselected past options are expected to affect subsequent decision-making. (Ben Jacob et al., 2006, p. 518)

Space and time are to be seen as the mediators of relationship, in which the internal commitments to change are configured to allow the meaning of ‘colony’ to be expressed through the individual actors. There is no need to interrupt this process in order to measure with rods and clocks exactly what space and time signify in their internal dimension. The origin of the concepts of space and time are the engagement of the individuals with their collective meaning. The essence of colony, which is encountered, lives in the arraying of individuals in space and time that allow the whole expression.

The bacteria effortlessly switch from a satisfaction with their own independence to a seamless fitting of their functional capabilities to serve a colonial organisation. The finiteness of their meagre capacity as single-celled organisms instead of being opposed to the cause of their unity, allows them to simply live their means in the unity they now adopt. The simplicity of means is not contrary to the attempt at unity but allows it to become.

The effect of a physical influence, say an electromagnetic field, as Ben Jacob describes, is to alter the response to a threat stimulus by changing the colonial form. In other words, the finite circumstances play through the adopting of unity to shape with context the particular expression of the whole.

This interrelationship of individual commitments and whole action is further evident in the act of sporulation. When the bacteria are unable to find food, they are able to commit their individual existences to alter the whole state into one of sporulation, or drying out their cells, to wait in spore state until more fortuitous circumstances arise. Ben Jacob discusses thus:

Sporulation is a process executed collectively and beginning only after ‘consultation’ and assessment of the colonial stress as a whole by the individual bacteria. Simply put, starved cells emit chemical messages to convey their stress. Each of the other bacteria uses the information for contextual interpretation of the state of the colony relative to its own situation. Accordingly, each of the cells decides to send out a message for or against sporulation. Once all of the colony members have sent out their decisions and read all other messages, sporulation occurs if the ‘majority vote’ is in favour. (Ben Jacob et al., 2004, p. 368)

The wonder then is not that this internal barter between billions of bacteria and their collective decision should occur, but how the inner potential and outer actualisation in the simplest of single celled organisms, informs the space and time of their experience with a collective action.

It is ridiculous to imagine such behaviour as determined by an external organisation as a system of number in which each individual bacteria is individually directed. Instead it is enough that the association of bacteria mark each others’ presence as significant in contributing to a realisation of their whole completion. The bacteria get the behaviour of their fellows, which before had been out of vision of their own individual lives, in order to found a future unity of completion, upon the basis of this collective holding of potential.

Development of life

Crucial for the development of life was the way the original bacterial organisms inhabiting the earth were able to use complex chemistry to obtain energy from their surroundings. The task they faced, without any chemistry degree or lab in which to practise, was how to profit from imbalances in the environment and early atmosphere in order to extract energy to fuel life. In principle, this process is almost impossible. According to the second law of thermodynamics, energy tends to go from ordered states to disorder. But life is conjuring up from disorder, the order of the organism as seen in complex metabolism. Moreover this conjuring trick of exploiting the environment for energy was solved not once but many times by living processes themselves, as the atmosphere changed. Finally photosynthetic bacteria cracked the hardest puzzle of all, obtaining energy from carbon dioxide, water and sunlight. To do this, they combined two earlier transformation processes to create a cascade of opportunistic reactions, leading eventually to the capture of energy into the inner electron flow of the organism.

The feat of arriving at such a complex manipulation of chemistry without any lab in which to experiment, demonstrated the fluid dynamic way in which the basic concepts of manipulation, the cell, the proteins, electromagnetism, are not inventions of man’s mind, but are the dance nature herself utilises. This understanding is further brought home in the discovery in 2007 (Engel et al.) that photosynthesis does not work in a mechanical way, transferring one photon of captured energy at a time, but in a entangled way, exhibiting a quantum beat of coherence. The coherence amounts to each act of transfer sampling all possible routes of excitation, before finding the path that best fits with the efficiency of the process over the whole. The result is an astonishing 95% efficiency rate of energy transfer, a startling achievement, far greater than comparable human devices can achieve (currently around 43%)! A wave-like coherence in activity is apparent over the system as a whole. The process exhibits a beat through time, which demonstrates a collective synchronisation of individual actions to harness energy.

The potential for collective meaning in the transfer of energy down one particular molecular pathway involves the simultaneous sampling of all states to determine a single individual course of action. In other words, whole and part, as is always the case in quantum systems, are inseparably interlinked. The individual act of the transfer of sunlight makes its contribution within a transformation of the collective state. The usual quantum paradox applies here. The whole and the particular both dynamically realise the other.

However there is a key difference here. The quantum correlations do not apply to an entity already existing. The efficiency of the transfer of energy gives definition to the photosynthetic organism. The coherence of quantum processes is rooted in the emptiness of potential out of which existence comes. Emptiness is able to join the disparate potentials on the edge of what makes life into a defining activity for the realisation of the whole. The photosynthetic process is engaging with the life/death process, where, at the edge of annihilation, molecules pool their collective touch with destruction into a vivid realisation of life.

It should not be underestimated what a feat it represents to efficiently tap (from sunlight, carbon dioxide and water) enough energy to fuel the organic process. Even a technological production developed by the most sophisticated of man’s inventiveness cannot achieve an efficiency that can even compete with the efficiency of the natural process. As seen above, the organism achieves a 95% efficiency at the very edge of what defines it as existence.

Not only does life solve the dilemma of making order from the disorder of the random state of the environment but it does so with an innate elegance and efficiency that is almost perfect (that is, 100% conversion of energy). The organism does not stumble accidentally across a boundary of form. It launches itself out of disorder into an almost perfect statement of whole organisation.

The cell relates to itself to become itself

The biological cell spans the entire evolution of life. The cell marks with a membrane, a territory of distinction inside. On the other hand, the cell only has meaning when seen for its ability to divide. That is, in the act of division, the cell is able to know itself (the divider cell) and to see itself as another, a copy of itself, as separate to itself (the divided cell).

There is in a sense only the first cell, that has divided itself many times, or the cell is the self- relationship whose meaning is the many cells.

The cell has a meaning because at the origin of life it was able to represent existence and found a way to make that existence again through its own living. Somehow it took what it was, this living thing, and found a way of making that living thing again. If the cell had never replicated, it wouldn’t be a cell. The basic relation is then shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16. A cell relates to itself (as a copy of itself) to become itself.

What we understand by a cell, is not just one thing but an endless proliferation into many. Part of what a cell is, is its ability to reproduce what it is.

The problem of going into the cell as a thing in the lab and taking it apart into genes and proteins is that one is looking at what the cell has become, out of the context of relationship. Modern systems biology is moving to the idea of relationship, but is holding on to the idea of the cell as an entity, as an elementary building block.

What makes the cell the cell, is the ability to relate to itself. In the act of splitting itself, the cell takes its identity and brings this identity out and completes itself in how it has made of itself a copy of itself. So the cell is the cell through life knowing itself and forming a relationship through what it is (into another one of what it is). From the beginning the cell was as much the ability to reproduce as any sole properties of the thing itself. The cell knows itself to become itself again. Everything about a cell, every property or characteristic of the cell, derives from the fact that first of all it is able to make itself into a copy of itself. Everything a cell is, starts from the fact that it is able to relate and in that relating it becomes everything it is.

The cell or any other element – an atom, a gene, a protein, a self – lives by knowing itself in relation to itself. The cell’s existence is not derived from its parts. Everything about the cell, its relation to the world, the relation of the whole to its parts, its relation to its self – all are included in the entity that knows its journey through the world as whole. The cell is an identity that takes up into the quality of change, a reference out of which life can orient its subsequent development.

The bounded existence doesn’t produce as a factory, something less than itself. It is able to reproduce exactly what it is, the whole entity. The cell stands in relation to something that is as real as itself. Its reality is totally defined by its relation. Everything that constitutes the cell is reproduced, so you can’t say what it is except in its ability to reproduce itself. The relationship in which the cell becomes the cell is the very nature of what defines it as a ‘cell’. The relationship is the essential part of what it is.

If you look at the cell and some of the properties that have evolved, for instance acquiring a nucleus with DNA as the basis of multi-cellular life, then these are new ways of the cell becoming the meaning of the relationship to itself. All the qualities it has, all the ways it sustains life, all follow from first of all reproducing a new copy of itself. Life expresses the same but differently as another. The relationship is able to understand itself in becoming another cell and another cell…

The relationship is paradoxical and changes the way we understand existence. There is no such thing as a cell out of its context. The cell is a cell by courtesy of the way it relates to itself to become itself, the cell in having this relationship to what it itself is, is always being born anew.

Identity and relationship arise together

Cells relate to other types of cells in order to find through these relationships, their own meaning of identity. In the same way the proteins and the genes that make them in the cell are involved in chains of relationships (proteins are able to activate and de-activate the production of other proteins) so that any one function of the body actually has a whole chain of active proteins involved. There is something that needs to relate to become itself and it does so by relating through other things, to make a network of relationships that end up identifying this thing through a whole lot of intermediaries in between, by which it becomes itself. Underlying a network of relationships, the identity is not a thing that has a relationship, but an existence that only is because of its relationships. It has to be in relationship to be itself. A cell has to be in this relation, to that relation, to this relation to be a cell.

Life isn’t stuck to one particular form. Who we are is in our ability to make ourselves anew. We can know ourselves as life and we can understand ourselves in that knowing from our experience into something new and we recognise ourselves again as who we are. It’s totally new. We’ve never done it before, we’ve jumped out, we were mathematicians and now we’re travellers. We do something totally new and it completes our relationship of who we are. We recognise who we are even though there is nothing similar in that new place. It completes our relationship to who we are. In fact we are more ourselves in having put ourselves out and made ourselves different.

So each time the cell makes a new type of cell, it is more than it was. Each time the cell becomes itself differently, it becomes more secure in what it is. We don’t need permanence, for our very existence is finding ourselves in relation and through that becoming who we are. The only way we can go is into the unknown, finding ourselves again and that’s all that the cell does. The cell doesn’t have a fixed existence. It finds itself in relation in different ways, in different contexts.

Mediation of forms

The slime mould gives a slightly different nuanced view of the colonisation process. The slime mould consists of individual amoebae that have autonomous lives of their own, until food scarcity draws them together. The call to unity now results in different roles being taken by the amoebae. A group of amoebae initiate the call to join together in a unified state. The leaders then form the head of a composite body called a slime mould which has all the characteristics of a single organism. It moves rather like a slug, with no sign that it is in fact composed of cells that are autonomous individuals. When finding an appropriate place, it forms a fruiting body. The initial leaders of the movement sacrifice themselves to form a hardened stem, while the other cells sporulate off branches of this central stem. This tree-like structure persists until conditions are again providential for life.

Once more we see here how the commitment to unity instructs the finite behaviour of the individual cells. The individual cells make choices, which are not confined to their own benefit. The behaviours thus lead outward from the individual into the expression of the unity of the pseudo organism, the slime mould. However the slime mould shows that there is no distinction between the individual actors and the whole organism they form. The individual amoebae could as well be the fixed cells of the organism. The behaviours by which the individuals know themselves in relation to the whole, are at the same time the unity organising itself through the individuals. In this latter regard the slime mould is no different to an organism made of cells.

The unity imagines itself into the necessary behaviours that allow the whole form to take on a temporary existence in the world for the sake of regeneration.

The bee dance

The individual bee does a waggle dance which communicates to the hive collectively, relative information such as the direction and distance to patches of flowers yielding nectar and pollen. The bee does a performance, which abstractly distils the context of the bees’ existence to a communal strategy of further exploration. The bee is a riddle standing between self and its action.

The insight of the bees agrees with Goethe’s approach to the plant. The conceptual relation of the bees’ relation to the location of the nectar is not a mental activity. The concepts of relation to the location of the nectar may be acted out in an abstract way into the code of a dance virtually conceived. This information gathered from the bees may then be lived forward into an activation of the navigation skills of other bees to the flower sites.

The concepts are not intellectual. The compass of bee activity that allows the bee to actively navigate a direction may be followed back into an abstract distillation of the essential map of the nectar’s presence. Concepts, as finite mediators of wholeness, have two expressions: they may be activated as physical skills of navigating the countryside in search of nectar, but also they may be questioned for their abstract significance.

Concepts are about the divination from the evidence of a direction that points in the way of the good of the whole.

The hive does not consist of a collection of bees who then sit down and work out a code of identification and communication of nectar sources, even many kilometres away from the hive. The activity of the bee dance is the action that defines the collective existence of the hive.

Caring about the world

The mistaking of conceptual reality for an intellectual understanding was brought out by a dialogue with a colleague. His stance was that reality was understood by reason alone. Angered by a loose comment implying the spiritual path, he set out to demonstrate by reason his viewpoint of rationalism.

My colleague wanted to establish once and for all the empty rational endeavour of life. As he honed in to making his point, the horizon of possibility seemed to visibly shrink, until what seemed a moment of total dissolution approached. Suddenly unity filled my heart with quite a different meaning from the situation. His wave of aggression broke against something solid.

Perhaps the feelings on a country bench

That the world was real, and I was too,

Or the sight of a moon, full and bright,

Its eyes turned away from the beauty-scarred earth

In giving myself up to the emptiness of approaching annihilation, the conceptual understanding of my experience in the world, re-formed about a whole communication of what it meant to live. The conceptual instead of breaking the world apart into divisions, gathered itself up at a centre of a map of making decision.

‘You can either care about the world or you can’t.’

The paradoxical frame of existence can only be tested in its living. Everything that is to happen through the acceptance of paradox is to be understood from this basic dichotomy that lives at the foundation of experience. At the same time, the insight is more than just an intellectual understanding. The paradoxical dichotomy also establishes a reference for the gathering of experience into the order of a defining meaning. The insight thus is something dynamic in my heart, already filled with the potential of event, to arrive at a unity of meaning.

The context of my journey is able to concentrate in me sufficient knowledge of my direction, to broadcast a sign, to alert others to the universal endeavour. An incompleteness of being draws out a symbolic form in which further development of a journey can happen across individuals. The signifying sign is transparent to the active meaning that later can be made through it.

The world reveals itself through the whole unity of what can become. The sign is a whole pointer from a partial state of realisation. The lines of realisation and negation (for both are allowed for in a journey that is yet to define itself fully) develop the whole sign so that the destination can bootstrap itself up from nothing. The realisation and negation lines come together in giving to the partial information, enough content to transmit and receive a common knowledge of passage.

‘You know not everyone thinks as we do.’

Goethe: