Another thing about Up Here was that you didn’t see many people dragging inert victims around the place. So far Muddlespot had only spotted one. That had been himself, hauling the stunned cupid by the heels past a Mirror of Harmony just now. It made him feel even more conspicuous.

He was beginning to sweat. He knew that because the floor had started feeling sticky every time he put a foot down. He was panicky and confused. Every professional instinct was screaming at him to reach down and rend his victim limb from limb (this was the accepted procedure back home). But he wasn’t at home. This was not Pandemonium. Up here, in this endless palace of light and music and order, even the smallest pile of entrails was going to start people asking questions.

He would have gone through the cupid’s pockets, only being a cupid it didn’t have any.

He dragged the body over to the wall and concealed it behind a thick tapestry of Calm. Then he hurried back to the point where he had made his attack and scooped up the arrow that the cupid had let fall. Well, that was Step One of the mission completed. Fifty per cent success rate so far, which was infinity per cent more than he had been expecting. Step Two was to get away with it.

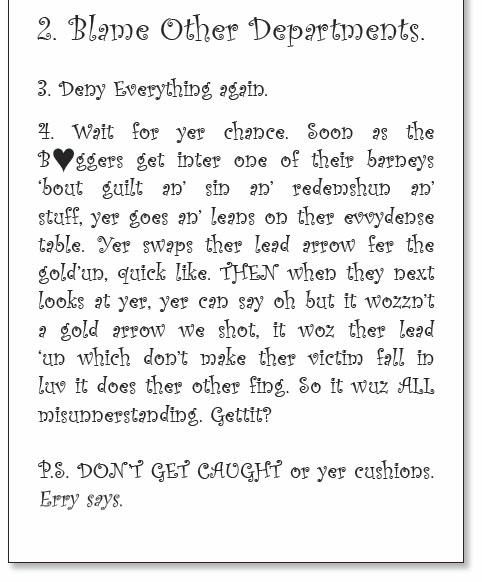

He gathered up the cupid’s papers in case they attracted attention. He glanced at the top one.

‘You bet,’ he muttered.

‘Change of plan,’ said Muddlespot. ‘Swapping arrows – bad idea. You just stick with points one to three and you’ll be all right. When you wake up.’

He hurried off to look for Windleberry.

Windleberry was not in the Hall of Ten Thousand Columns, where a choir was beginning to tune up for a practice. He was not in the Gallery of Green Sunsets, where angels flowed busily to and fro on a myriad of different errands. He was not in the Chamber of Stars, which was absolutely crowded with—

‘Oi!’ called a voice. Muddlespot looked around. Mistake.

A cupid was fluttering down the corridor towards him. Muddlespot clutched the huge sheaf of papers to himself, sheltering behind them as far as he could.

This cupid too was out of breath.

‘You seen Spikey?’ Its eye fell on the arrow and papers. ‘He give you those?’

Muddlespot’s brain, fired by terror, moved at lightning speed. ‘Spikey’ must be the pink cupid who was now slumbering peacefully behind the tapestry in the corridor outside the Dept of Luv Stors.

‘He – er – took a break,’ said Muddlespot.

‘Took a break? Cheeky bugger! Got you to stand in for him, did he? I bet. Who are you, anyway? I’ve not seen you before.’

‘I’m, er, I’m new.’

The cupid blew out his fat cheeks. ‘This ain’t one fer a newbie. Spikey should know that. I’ll twist his neck when I catch him.’

His neck’s a bit fat, actually, thought Muddlespot. I went for the back of the head myself.

‘I’ll handle it,’ he said as brightly as he could. ‘I’m ever so eager to please. Just point me in the right direction and leave me to it.’

‘Point you? Boy, I’m taking you. You don’t arrive and do like you should it’ll be my neck that gets twisted. Come on – we’re late!’

‘Oh no, really, I’m quite sure I can handle it . . .’

‘Come on!’ cried the cupid, fluttering a little ahead of him. ‘They won’t wait – Hey! What happened to yer wings?’

‘Wings?’

Some aspects of Muddlespot’s disguise were really rather weak. Some didn’t exist at all.

‘I’ve – er – I’ve been grounded,’ he said desperately, waddling after the cupid as fast as he could.

The cupid cackled. ‘Yer can’t be that new, then.’

‘Are you sure of that . . .?’

As he ran, Muddlespot’s eyes flicked left and right, searching for a way of escape. If he could just lose himself in the crowd, somehow? But that was going to be tricky, when the cupid could fly and he couldn’t. Maybe he should wait for some lonely corridor somewhere.

Trouble was, there didn’t seem to be any. Every room or hall or chamber they entered seemed to be larger than the last, and with more and more people in it. They seemed to be heading towards the centre of things.

‘Er – where are we going?’

‘Din’t he tell yer ANYFING? Appeals Board, of course.’

The boys had been sent off to P.E. The girls had been kept back. Mr Singh had been called in. Things were getting predictable.

‘. . . Now it seems that there have been some things that are very silly going on,’ Mr Singh was saying as he paced up and down the rows. ‘I am very disappointed to hear about it. It seems that some people are not living up to the standards that we expect at this school . . .’

One to one Mr Singh was quite effective. He was all turban and bushy brows and seamlessly interwoven moustache and beard and 100% eye contact. He talked, you listened.

Put him in front of fifteen girls at once, though, and he wouldn’t manage to make eye contact with any of them. He would march up and down to the sound of his own voice while fifteen girls waited until he finished. Then he would nod and walk out again.

‘. . . Respect for one another. And also for their property. To remove the property of another pupil without their permission is theft. Even if the intention is to return it at some point . . .’

Sally knew she should just sit it out. She always had done before.

‘. . . very seriously. I assure you I am not joking . . .’

Except for one thing. Before, she had always been innocent.

‘. . . I very much hope, indeed I expect, that that musical instrument will be returned before four o’clock. It is a very serious thing to cause a fellow pupil to miss an exam . . .’

As long as he was still marching up and down and talking, Sally thought, it was OK. And when it got to ‘I-expect-anyone-who-knows-anything-about-thisto-come-and-see-me’ it was probably still OK. But if they got on to searching the corridors before the next break it was going to be bad. Stashing the oboe in her locker hadn’t been a clever thing to do. She had been totally focused on getting it off Janey, and by the time she had done that there hadn’t been a moment to think what to do next.

Theft. He had said it.

If she just handed it over to Imogen, or indeed to Mr Singh, everyone would think it was Billie or Holly or someone like that who had taken it, even if they didn’t think it was Sally herself. There would be some tough questions. And not answering tough questions when asked would mean Big Trouble. She had to find a way of covering her tracks. She couldn’t think of one.

I’m no good at this, she thought. I’m only good at being good.

Her palms were prickling and her throat felt tight. If he stopped and looked at her. And she looked back . . .

Janey could look innocent when she wasn’t. Everyone else could.

Sally didn’t know how to.

‘. . . I need hardly say that there will be the most serious consequences . . .’

It was unreal. It was like being in a dream, just as it starts to turn into a nightmare. The room around her seemed to be huge. The ceiling was almost out of sight, lifted high above her on great marble columns. White marble benches circled around her, rising like flights of giant steps, and all of them were empty except for the very highest row where a huge, brooding presence looked down upon her with eyes of ice. She felt very small.

And for some reason, she also felt very sticky.

Words seemed to float before her, written on a page she held. They said: Deny everything.

Somewhere a voice was speaking, as if from a dream. She could not quite hear the words that it was saying. But she knew what they must be.

It’s all your fault, isn’t it? You started all of this.

Deny everything. She couldn’t possibly do that. She didn’t know how.

It is all your fault, isn’t it? the voice insisted. It was you.

Yes, she whispered in her mind. Yes, it is. Guilty.

‘Guilty!’ squeaked Muddlespot.

There was a huge, shocked silence.

‘What’re yer doin’?’ hissed the cupid beside him.

Muddlespot could not answer. He could not think. He could only look up, and around, at all that huge chamber and the presences within it, centred upon him where he stood quivering in the witness stand.

(Well, not exactly on him. Even now the attention, though keenly focused, remained averted from the point of greatest interest.)

There were the vast, living statues, soaring all the way up to the row of six eyes that peered down like eagles from a cliff-side nest.

There was the woman standing on the platform, with an angel at her side. Both seemed suddenly to have woken up and started to pay him attention.

There was the huge angel in the galleries, dark-robed, dark-winged and with eyes that sent blasts of chill through Muddlespot’s spine. Muddlespot had felt his presence looming there the moment he had scuttled into the courtroom. He felt it now, bearing down upon him, suddenly intent, like a hunter who has seen something twitch among the grasses. Muddlespot was trying to look everywhere but up. Even so he knew that angel was there.

‘The Witness is not required to enter a plea . . .’ came a voice from high among the heads of the columns.

‘But on a point of order, your Graces,’ said the great angel.

He said it in a voice of such cold calm that it got even the living statues’ attention.

‘The Statement of the Witness would seem to require clarification. Are we to understand that his Department now accepts responsibility for the answers given to, I believe, 2304(a) through to 6823(d) iii, including the questions on Adultery, Illegal Marriage, War and Destruction . . .?’

All eyes were on (or near) Muddlespot. His mouth was open, his limbs were locked in terror. He had barely heard what was being said.

To make it worse, in his efforts to avoid looking up at the dark angel, he had glanced to his right and found that there was one set of eyes in the courtroom that were definitely not averted. They belonged to a grey-skinned fiend from Pandemonium, seated on the lower benches, who was leaning forward and staring at him. Its gaze seemed to peel back his layers of flesh-coloured paint, as if it suspected something that no one else did.

Somewhere far away a voice seemed to be checking over the list. War, yes. Destruction, yes. Illegal Marriage, pretty much. Adultery – well, no, but that’s a detail . . .

The voice sounded like Sally.

‘Yes!’ Muddlespot squeaked. ‘Yes we do. It was our fault. We admit it. Everything!’

‘Wot the . . .! ? !’ hissed the cupid beside him.

Deny everything, whispered the papers that he clutched to his chest.

Too late.

‘But . . .’ said the smaller angel who stood beside the woman on the platform. ‘But – if we understand the witness correctly – then I submit, Your Graces, that my client has after all no case to answer?’ He sounded as though he could hardly believe it himself.

There was a long and heavy silence.

‘It would seem not,’ said the Voice From On High.

The cupid swore, once, and flew out through the exit like a bumblebee on turbo.

‘And that my clients have a claim for redress for wrongful detention, false witness, defamation of character, personal distress, official misconduct and misdirection in each and every one of forty-one hearings over three thousand years?’ said the angel on the platform, gathering speed as it emerged from its state of surprise.

‘Don’t push your luck,’ said the Voice From On High.

The silence returned.

‘This testimony bears on many cases,’ said the Voice From On High. ‘There are Implications to Consider. The Court will Adjourn.’

Uproar! Voices from everywhere! Angels that were Counsels, Clerks and Ushers, Callers and Trumpeters and Scriveners and Scruplers all appeared in a shining throng and began arguing furiously with each other about what it all meant. The doors burst open and in rushed a whole host of other Guardians who had spent the last three thousand years waiting for their own humans’ cases to be heard, and they all cheered the Guardian on the witness stand and slapped it on the back and tossed it in the air to cries of ‘Hip, Hip Hoorah!’ and ‘For he’s a Jolly Good Angel . . .’ and so on. The sudden turmoil tumbled Muddlespot from his place. He was knocked this way, pushed that, lost his footing and found himself crammed up against a table made of rose petals, on which rested an arrow exactly like the one he held in his hand except that its head was gold. The part of his brain that had not completely lost the plot (about 10% of it) remembered that it was here for some reason to do with collecting arrows. Signals fired urgently to his jaw (which was the only part of him capable of gathering anything because his arms, feet and tail were all variously committed at the time). He snatched it in his teeth and squirmed away through the crowd.

Behind him, the woman on the platform looked around. There was a question in her eyes, but no one spoke to her.

Slowly she took a step from her place. Then another. Then she walked down the stairs and quietly out through the doors: out into Heaven at last, after three thousand years. Behind her on the platform the marks of her feet remained, worn into the stone over the centuries of shifting her weight from one to the other while she waited for her judgement to pass.

In the gallery a slow smile spread over the face of the dark angel.