Lung: The Breath of Life

On one side heavenly fire: light, thin, in every direction the same as itself … The opposite is dark night; a compact and heavy body.

Parmenides, On Nature

IN ONE OF THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENTS where I used to work there was a concealed door that led to a small yard out back. Ambulances would bring patients there when they were already dead. Rather than arriving with flashing blue lights at the main entrance there would be a discreet knock on the door, and one of us doctors would go out and certify the body so that it could be taken to the mortuary.

There are only three tasks to remember when certifying the dead: shining a torch in the eyes to see if the pupils narrow in response to the light, checking the carotid artery at the neck to feel if there’s a pulse, and putting a stethoscope on the chest to hear if there’s any breath. The breath is the most telling; in Renaissance times a feather would be placed on the lips to see if air was moving in and out of the lungs. The textbooks recommend a full minute of listening, but I’ve often done it for longer – afraid that I’d miss an agonal gasp, or one final, feeble beat of the heart. But a glance at the milky, desiccating surface of the eyes is usually enough to convince me that the dead really are dead. The yawning emptiness of the pupils is another giveaway – a glimpse into the abyss.

One night a man was brought in dead after he’d jumped from one of Edinburgh’s many bridges onto the road below. His medical notes, when they arrived from the records department, said the psychiatrists had seen him earlier that week, and he’d seemed in ‘good spirits’. Bystanders said he’d had no hesitation; just leapt over the parapet to his death as if he’d dropped something precious and wanted to get it back.

His was a messy corpse. His neck was badly broken and distorted, his tongue and neck were swollen, but there was little bleeding from his grazes – his heart would have stopped beating almost immediately on impact. I shone a torch into his eyes and watched the light drop into their vacant stare – there was no narrowing of the pupils, or reflection of the light from their surface. Moving onto his carotid pulse I felt something unexpected: beneath my fingertips there was a popping and crackling sensation. After checking he had no pulse I placed my stethoscope against his chest wall and heard the same crackle amplified through the earpieces. His lungs must have burst, I realised – exploded with the pressure as he hit the road. The popping and crackling was caused by air, ordinarily contained within the lungs, but now tracking out into the other tissues of the body.

Liquid and air must keep to their separate compartments in the body, just as a horizon separates the sea from the sky. Even if his eyes and lack of pulse or breath sounds hadn’t convinced me he was dead, this would have. As I listened for a breath sound that didn’t come, I imagined how it must feel to launch oneself from a bridge; how light and free it might feel if only gravity, and the blackness of despair, weren’t pulling you down to the earth.

LUNGS ARE THE LEAST DENSE organs in the body, because they are composed almost entirely of air. The word ‘lung’ comes from a Germanic root lungen, which itself arises from another Indo-European word meaning ‘light’.

Traditional Chinese, Ayurvedic and Greek medicine all maintained that air carried invisible spirits or energies (which they called, respectively, qi, prana or pneuma). From those perspectives our bodies are bathed in spirit, our lungs the interface between the spiritual and the physical world. For the Greeks, as commemorated by St John’s Gospel, the first principle was logos – the word – existence was conjured into being through sounds produced by the breath. Written texts, even those never intended to be read aloud, are often punctuated according to the needs of a speaker to take a breath.

The lungs are light as spirit because their tissue is so thin and delicate. The membranes within them are arranged so as to maximise exposure to breath, much as the leaves on deciduous trees maximise exposure to air. Just as leaves draw in carbon dioxide and leak oxygen, lungs draw in oxygen and leak carbon dioxide. If you were to stretch flat all the membranes of an adult’s lungs they would occupy over a thousand square feet; equivalent to the leaf coverage of a fifteen- to twenty-year-old oak. Listening with a stethoscope you can hear the flow of air across those membranes, like the rustle of leaves in a light breeze. When doctors listen to the breath, that’s what they want to hear: an openness connecting breath to the sky – lightness and the free motion of air.

Doctors use stethoscopes to sound out solidity in the lungs: if tumour or infection consolidates the tissues, instead of the muted sigh of the breath you can hear the whistle and clatter of disease. With a stethoscope we listen for ‘increased vocal resonance’: the crisp transmission of words spoken by the patient. We listen for ‘bronchial breathing’: the sound of air whistling through the large airways. These sounds are inaudible through healthy tissue, but can be revealed by the transformed acoustics of a heavy, solidified lung. Infection rather than tumour gives rise to a third sound, called ‘crepitation’, when pus and mucus make the finer membranes stick to one another. Thousands of tiny air chambers then pop open and closed with each waft of breath, sounding as if the lungs had been enveloped in a thin film of bubble wrap.

When I think about lungs, the associations that come to mind are of light, airiness and vitality. When they become diseased they lose their lightness; they become ballast that pulls us towards the grave.

IT WAS A COUGH that Bill Dewart complained of first; an empty, futile cough that punctuated his sentences by day, and earned him digs in the ribs from his wife at night. Bill wore a flat cap and carried a stick, but at seventy-six was strong and still working as a plumber. He had the face of a younger man, with a surprised expression, as if startled by how stealthily age had sneaked up on him. ‘What would I stop working for?’ he asked me when I brought up the question of his retirement. ‘Sitting around at home all day, getting under my wife’s feet.’

‘How much do you smoke?’ I asked him, noticing the tar stains on the fingers of his right hand.

‘Forty a day for the last sixty-five years,’ he said, ‘and I’m not about to stop now!’ He laughed, the folds of his skin deepening across his cheeks: ‘Cigarettes!’ he said, wagging the yellowed finger at me. ‘That’s all you doctors want to talk about!’

I asked him to blow through a flow meter, to see how fast he could expel air from his chest. It was slower than it should have been at his age, but the smoking would explain that. After helping him unbutton his shirt, I placed my left hand against the back of his chest, and began to tap that hand’s fingers with the middle finger of my right. Over healthy lungs this tapping makes a sound like a muffled drum; resonant and soft, with a slight give felt in the left hand. When lung tissue is solid or filled with fluid it’s like tapping the drum’s rim rather than its skin: dull and hard, without any give.

I sounded all the regions of his chest: front and back, upper, middle and lower. All sounded hollow. I tracked the same route using the stethoscope: the sound throughout was of soft rustling leaves – there was no sense of a solid portion of lung beneath my hands. Lastly I had him say ‘ninety-nine’ while I listened over the same areas (the ‘n’ sound resonates particularly well through the chest). Left and right, upper and lower, front and back, the transmitted words were soft and indistinct. There was none of the crispness that I’d expect of sound transmitted through consolidated lung.

‘I don’t think you’ve got a chest infection,’ I told him. ‘And I can’t see that any of your tablets cause a cough.’ I glanced from his face to his tar-stained fingers. ‘But I’d like to do some blood tests, and send you for a chest X-ray.’

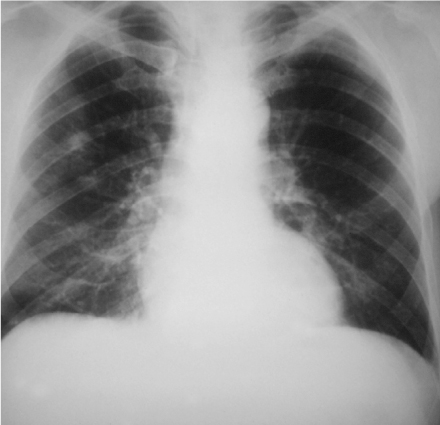

ON THE RESPIRATORY MEDICINE wards I had two teachers. One of them claimed membership of a lofty tradition in clinical examination, and instructed us to practise percussion of the chest by placing a coin beneath a telephone directory. ‘Shut your eyes and tap the telephone directory,’ she said, ‘the acoustics over the coin are slightly different.’ She insisted that examination of the lungs was a fine and subtle art that could be improved upon throughout a clinical career. The other teacher thought that this was the auditory equivalent of examining bumps in the skull to divine personality, or tasting urine for sugar. In the first tutorial he gave, he held up a chest X-ray against the window. ‘This,’ he said, ‘is how you examine the chest. With X-rays.’

Bill Dewart’s X-ray looked pretty normal to me. His windpipe was straight, ending in the Y-fork that branched out into each lung. His lungs themselves looked dark, without a trace of the density that can suggest tumour or infection. If anything they were too dark, suggesting emphysema caused by those sixty-five years of cigarettes. His heart was of normal size with respect to the diameter of his chest, and the outline of his diaphragm was distinct rather than hazy. Apart from the emphysema the only abnormality I could detect were some knuckle-like thickenings on the ribs of the right-hand side. ‘Did you ever break your ribs?’ I asked him.

‘Aye,’ he said, wincing at the memory. ‘But the other guy came off worse.’

‘So all in all, I can’t see a reason for your cough,’ I said.

‘Maybe it’s getting a wee bit better,’ he said, but I was unconvinced.

‘Let’s try an inhaler, send a sample of your phlegm to the lab, and meet again in a week.’

‘THE COUGH’S WORSE than ever,’ he said when he came back to me. ‘Not just that but my wife says I’m losing weight. I eat like a horse but I can’t put anything on.’ Again I tapped the different lobes of his lungs; again I listened to them, but didn’t hear anything unusual. ‘And that inhaler is a waste of time.’

‘It’s early yet,’ I said. ‘It’s worth persevering.’

‘Well don’t persevere too long,’ he said, ‘or there won’t be anything left of me.’

I started him on high-calorie drinks, and issued him with a dietician’s advice sheet advising chocolate bars between meals, and smothering all his meals in cheese. I also arranged a follow-up X-ray, and wrote to the respiratory specialists asking if they’d do a CT scan of his chest.

The second X-ray report was sent electronically only a day later – the radiologist had felt it too urgent to wait for the mail. ‘Comparison is made with the previous film,’ it said. ‘There is a degree of mediastinal widening and some deformation of the right main bronchus suggesting subcarinal lymphadenopathy. Further CT examination is recommended.’

The ‘carina’ the radiologist was referring to was the point where the trachea splits into two separate tubes, one for each lung. ‘Carina’ is Latin for ‘keel’, and is used to describe parts of the body where two sloping planes meet a central ridge, just as the two halves of a hull meet along the keel of a boat. There are two other carinas in the body: one under an arching band of tissue in the brain, where it links parts of the two hemispheres related to memory, and one in the lower vagina where the urethra indents the vaginal wall.

The carina is the most sensitive stretch of the human airway: it’s the place where any object falling down the windpipe, such as a flicked peanut or a lump of choked food, is likely to strike first. It has to be sensitive because anything falling into the lung must be coughed out immediately, otherwise infection or suffocation might follow. Swelling around it can bring about a particularly persistent and distressing cough, as the body tries to expel whatever is causing the irritation. The radiologist was suggesting that the lymph nodes under that keel of tissue had become heavy and swollen and, like a boat burdened with too much ballast, the hull of the airway was bent out of shape.

The CT scan confirmed the swollen lymph nodes around the end of Bill’s trachea, as well as in the area where the airways, arteries and veins enter and leave each lung. The lymph nodes of that region drain fluid from the lung tissues, and the fact that they were swollen suggested they were weighed down with tumour cells. But there were other possibilities: infections and some unusual immune conditions. To find out which, Bill would have to undergo a biopsy.

IF YOU BLOW AIR onto your hand with your mouth open, your breath feels warm and moist. If you purse your lips and blow again your breath this time will feel cold. It’s a Renaissance belief that your soul is attached most firmly to your body at the lips; after all, it’s the place where the breath of life enters and leaves your body. That the breath can change between warm and cold just by altering the position of your mouth was once powerful proof of its vitality. The truth is a little more prosaic: the pursing of your lips puts the air under pressure; it’s the re-expansion of that pressurised air that draws in heat from your hand and makes it cool.

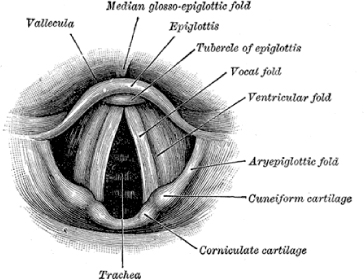

When you breathe in through your nose, air is channelled by folds in the nasal bones called ‘turbinates’ that roll the air like turbine blades. They slow, warm and moisten the air as it makes its way to the back of the nose, where the front of the spine makes its joint with the skull. From that angle – the ‘post-nasal space’ – it is redirected down behind the tongue, into the laryngeal cartilages and between the false and true vocal cords. The anatomical landscape that makes voice from breath is intricately named: triticeal, corniculate and arytenoid cartilages; cuneiform tubercle and aryepiglottic fold.

Muscles in the larynx alter the tension between these different elements giving pitch to the voice, whether we’re screaming in alarm or singing an aria. From the vocal cords the breath flows on another five or six inches to the carina, then, like water around a hull, the airstreams divide into the right and left lungs.

The right lung is larger than the left because it isn’t compressed by the bulk of the heart. The airway leading into it is more vertical too – if a peanut or a button is inhaled it’s likely to fall into the right lung. From the lung root, where the great vessels enter and leave, to the leaf-like membranes at the periphery, the airways of the lung resemble a tree – specialists even use the term ‘bronchial tree’ to describe them. Their anatomy has been carefully worked out not just because children inhale little objects that have to be retrieved, but to aid surgery. If you want to chop out a lung tumour, root and branch, you have to remove the affected segment of lung as well as the branch of the airway that supplies it.

THE LYMPH NODE BIOPSY confirmed what I had feared: though the X-rays had originally been clear, Bill had lung cancer. The position of the tumour, and the fact that it had already spread, meant that surgery would not be an option. Doctors have an odd term for the quantity of cancer that builds up within an organ; they call it ‘tumour burden’. As Bill’s lungs became heavier, his body and voice became lighter, more insubstantial. At first he still managed to come down to my office to see me, but within a couple of months of his biopsy I was pedalling out to his house every fortnight or so to visit him. He remained as stoical as ever. During these meetings he’d usually have a cigarette in his hand, his nostrils billowing smoke like twin factory chimneys. He’d decided it was too late to bother quitting. As the smoke hovered in clouds over his head it seemed to give shape and substance to his words.

As the weeks went by his tumour grew, and as his lungs became heavier the sounds I heard in his chest began to change. I could hear the breath whistling at his carina, his voice crisply clear as it transmitted through his solidifying lung. It wasn’t long before he needed supplementary oxygen to move around the house, delivered by little tubes worn over the ears and passing under the nose. Because oxygen is considered risky in the house of a smoker, he finally had a reason to quit the cigarettes. I asked him how difficult it had been to stop and he flashed one from his library of smiles. ‘No bother at all,’ he said, ‘I should have done it years ago.’

He’d been diagnosed in the autumn, and by spring he’d had his easy chair taken out of the living room and a hospital bed installed. ‘Fantastic, Doc,’ he said with a grin as he showed me the electric buttons that would raise and lower it, sit him up straight or lie him flat. ‘It’s almost worth cancer to get hold of one of these.’ He laughed, but his wife didn’t.

There are landscapes, often of limestone, where tunnels within the earth truly breathe: they exhale in the heat of the day, and inhale as the earth cools by night. One afternoon, when I went in to check on him, his breath was like that: cold, slow and carrying the memory of having been deep underground. ‘Look up there,’ he said, pointing up the hill where a stand of trees was greening with the spring. ‘Do you know what’s through those trees?’

I followed the direction of his finger. ‘No, from this angle I’m not sure.’

‘The crematorium,’ he said. After a few moments he added: ‘I’m not scared. When I’m so breathless I can hardly move, I see smoke from its chimney and think it might not be so bad to be up there, blowing over the city.’

The wind was invisible, light as spirit, seen only in the motion of the trees and the smoke, which on that day at least was carrying the ashes of somebody else.