Kidney: The Ultimate Gift

Nowadays it is possible to say that lives are connected, by transplant, across the thresholds of life and death.

Alec Finlay, Taigh – A Wilding Garden

IN THE INDIAN FOOTHILLS of the Himalayas there’s a Tibetan hospital that serves the community around the home of the Dalai Lama. Between training in emergency medicine and beginning in general practice I worked there for a few months, managing the leprosy, dog bites, tuberculosis, dysentery and injuries of the local Tibetan population. It was a general hospital that turned no one away, and the job involved delivering a lot of babies and looking after two wards full of patients, as well as outpatient clinics twice a week. Through translators I’d labour to understand fifty or sixty newly arrived refugees, most of who were suffering from stress headaches, indigestion, homesickness or diarrhoea. Occasionally there’d be a forlorn westerner in the queue, pale and emaciated with dysentery they’d picked up by drinking unfiltered water. ‘I want to live like the locals,’ they’d say; I’d inform them the locals got dysentery too.

There was an alternative to the hospital: just down the road was the Tibetan Medical and Astrological Institute. Traditional Tibetan medicine is an ancient system involving the manipulation of five elements and three humours – practices resonant with Vedic and Hippocratic perspectives on the body. Those patients with vague aches, and unusual constellations of symptoms that we couldn’t make sense of, often did well with the traditional Tibetan physicians. I often wish I had a comparable clinic down the hill from my office in Scotland.

Out of curiosity I visited the Institute, a grand whitewashed building set among pine trees, on the spine of a ridge coming down from the Himalayas. Great charts of the human body were hung on the walls inside, overlain with meridians and lattices of lines, like the contours and grid squares on a map. Sometimes I understood the rationale for a particular Tibetan treatment, but for the most part it was a mystery – my understanding of the body didn’t concord with theirs at all. If the kidneys weren’t working, for example, the traditional practitioners thought that it was because the organs were too cold. The diagnosis ‘cold kidney’ was an illness all to itself, called ‘k’eldrang’. Treatment of k’eldrang involved the avoidance of cold or wet seats, strains to the back, and certain foods thought dangerous for their cooling properties. In severe cases ‘moxibustion’ was recommended: an ancient practice with its roots in Chinese medicine, which uses burning herbs to heat the skin over particular meridians.

Tibetan customs of pilgrimage include carrying stones from place to place over the landscape. It’s a practice I recognised from Scotland, where walkers often leave stones on the high ground of a particularly difficult or exhilarating climb. Once, when visiting a Tibetan monastery’s prayer rooms, I saw an old monk touching a pilgrim on the head and back with a special stone – it was smooth, dark and shaped like a kidney. I asked what was being done. The stones can heal, I was told; being touched by them can rebalance the flow of energy within the body.

Traditional Tibetan medicine seemed to have some success, but I was doubtful that sacred stones could be successful against kidney disease or renal failure.

THE WESTERN UNDERSTANDING of the kidney was slow in coming. Kidneys strain urine from blood, even Aristotle knew that, but as late as the fifteenth century one of the great Renaissance anatomists, Gabriele de Zerbis, still thought that the upper half of the kidney gathers blood, then strains it through a membrane strung across the middle of the organ. Anatomists like him had cut through human kidneys and can’t have seen any such membrane, because it isn’t there. Perhaps they wanted to believe in the existence of one so much that they saw it.

De Zerbis was a professor at Padua in north-east Italy, and wrote one of the first treatises on the medicine of old age – Gerentocomia – in the late fifteenth century. To retard the advance of old age he advised living somewhere with an easterly exposure (north-east Italy perhaps?), plenty of fresh air, and to eat a combination of viper meat, a distillate of human blood, and a concoction of ground-up gold with precious stones. Esteemed throughout the eastern Mediterranean as a specialist in medical care of the elderly, de Zerbis was called to Constantinople in 1505 to treat a member of the Ottoman elite. The old Ottoman died, and so de Zerbis was caught, tortured and sawn in half, just like one of his dissected kidneys.

De Zerbis’s successor at Padua was Vesalius, a Dutchman who effected a revolution in anatomy and medicine (in those days, there was little distinction between the two). Vesalius took the innovative step of describing what he saw, rather than what the textbooks, some of them dating back to Roman times, told him he should see. He cut kidneys in half and saw no membrane. He still thought that kidneys filter blood in some way; he just admitted he didn’t know how they did it.

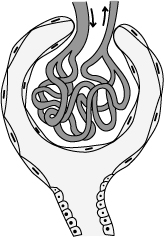

No one would come closer to the true mechanism until microscopes became commonplace a hundred and fifty years later, following advances in lens and prism technology. In the 1660s, lenses were achieving transformations in the understanding of both inner and outer space: near Cambridge, Isaac Newton, in quarantine from the plague, used his time to demonstrate how sunlight can be broken into colours by a prism, and formulated his laws of gravity. In London, Robert Hooke published his Micrographia, which showed the astonishing intricacy of tiny, everyday structures, such as body lice, pieces of cork, and flies’ eyes (he coined the word ‘cell’ as the basic unit of life, because under the microscope they resembled a series of monks’ cells). Around the same time, the professor of medicine at Pisa, Marcello Malpighi, used the microscope to demonstrate how blood and air did not mix freely in the lungs, but were merely brought closely together. He also revealed how capillaries in the kidney formed tiny sieve-like structures. He saw that the pale, central portion of the kidney was composed of masses of tubules; when squeezed these tubules produced a liquid that tasted just like urine (before biochemistry labs, the analysis of substances was often left to the tongue).

It took another two hundred and fifty years – until the early twentieth century – to understand the function of the kidney: the way renal blood vessels form a knot of capillaries which filter toxins into a cup-like receptacle at the head of each tubule. As vital functions go, it’s one of the simplest that the body performs, but even so the subtleties of the process have proved fiendishly difficult to understand.

The function of the kidney seemed enticingly simple to replicate: the first attempt at building an artificial one took place as early as 1913. The machine was tried on dogs, with an extract of ground-up leeches used to prevent blood clotting inside it. Thirty years later, a Dutch physician, Willem Kolff, invented the first functioning kidney ‘dialysis’ machine for humans, which would artificially filter toxins from the blood – he didn’t patent his machine, because he wanted others to develop it and make it more widely available.

Kolff initially worked under the scrutiny of Nazi occupation, but in secret he was a member of the Resistance. His first machine used the newly invented cellophane from sausage manufacturers, orange-juice tins and a water pump he obtained from a Ford dealer, but he refined it sufficiently so that in 1945 his machine saved the life of a sixty-seven-year-old woman. In 1950 he emigrated to the US and developed the process even further. As he was working on his dialysis machine, and more patients with kidney failure were beginning to benefit from it, something near miraculous happened: the successful transplant of a kidney from one body to another.

The apparent simplicity of kidney function led to the idea of building an artificial one, and the simplicity of kidney anatomy – one artery and one vein, and only one outflow for urine – meant that it was the first whole organ to be considered a candidate for transplant. The first kidney transplant in humans was attempted in 1951, but failed because the immune system of the recipient rejected the ‘foreign tissue’ of the donor’s kidney. In 1954, at Brigham Hospital in Boston, this problem was circumvented by transplanting a kidney between identical twins, one of whom had suffered double kidney failure. The recipient’s body was genetically identical to the donor, and so there was no rejection. It was the first time in history that an organ had successfully switched bodies.1 The next twenty years saw a tremendous advance in the understanding of the immune system, and how to improve the recipient’s tolerance of the foreign, transplanted tissue. By the late 1970s such operations between genetically dissimilar individuals were almost commonplace.

BRAIN TISSUE can only survive for a few seconds without blood, but kidney tissue is much more resilient – if kept cold an extracted kidney can survive for twelve hours or more (though the quicker it is transplanted the better). This means that kidneys can be taken from someone recently deceased or brain-dead, or even from a live donor, many hundreds of miles from where someone is waiting to receive it. National databanks now match recipients to available kidneys; the immunological profile of each is compared so that the chances of rejection are minimised. The kidney for the first transplant I saw had arrived by air from a city three hundred miles away. Its former owner had died that morning, and it was transported to theatre in a cooled polystyrene box.

Between the surgeon and myself lay Ricky Hennick, a man in his thirties who had suffered total kidney failure many years before as a result of infections. He’d been kept alive during those years by dialysis. Only his lower abdomen was visible between the piles of green drapes; he’d been cut not in the back, where his own scarred kidneys lay, but on the lower left of his belly, making an opening into a cavity called the ‘left iliac fossa’. There are good reasons for this: when putting a new kidney in there’s no reason to take the ‘old’ ones out. The iliac fossa is relatively easy to access, and there are wide arteries and veins for the new kidney to be plumbed into.

The surgeon had opened a hole in Hennick’s iliac fossa just above those iliac vessels. They had been dissected free of the tissues, raised up in loops, and closed off with metal clamps. One of the nurses opened the polystyrene box and I looked into it with astonishment; the kidney was cold, shrunken and a dusky grey – barely recognisable as an organ. It was lifted out and laid snugly into the hole in Hennick’s abdomen. An assistant, one of the department’s senior registrars, dripped ice-cold solution into the cavity to prevent its tissues warming to body temperature.

Hennick’s iliac artery and vein, as well as the artery and vein of the new kidney, were spliced together with neat embroidery stitches. Then the surgeon took a deep breath, stretched his arms like a stage conjurer, and said to me: ‘You’re about to witness the most wonderful sight in the history of medicine.’

He removed the arterial and venous clamps in sequence, and Hennick’s blood began to pump into the withered kidney. Each beat of his heart, visible in the pumping of the arteries, caused the kidney to swell. It was like watching a process of reanimation: a refutation of death. As the kidney grew, its defeated, dimpled surface began to fill out to a lucent pink. The surgeon held up the ureter of the new kidney (the tube which carries urine to the bladder) and I watched as a bead of urine began to grow at its cut end. ‘It’s working,’ he said with triumph. ‘Now we can stitch it into the bladder.’

Hennick’s bladder had been filled up with antibiotic solution by way of a catheter, and its outer surface stripped of fat. A tunnel through its outer tissues was made, about an inch long, and the ureter threaded through. At the far end of the tunnel a hole was cut into the bladder, and the ureter stitched into the free end. The surgeon placed a clear plastic drainage tube into the scar he’d made in Hennick’s abdomen, then closed up his muscles and skin.

The operation was over: Hennick would be free of dialysis for life, although he’d rely on powerful drugs to prevent rejection of the new kidney by his own immune system.

A SUCCESSFUL KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION is a triumph and a celebration, but is often achieved through exploitation of a tragedy. Until recently, kidneys for transplant have been obtained largely from the dead. Being involved in a successful transplantation is bittersweet; the relief of a life that has been saved is balanced by regret over the life that has been lost. I remember one that worked out successfully for several recipients, though catastrophically for the donor.

It was a night shift, 3 a.m., in a provincial emergency department. Paramedics were on their way with an unconscious teenage girl suffering a severe asthma attack. They had passed a tube into her windpipe to help her to breathe, but even with its help they couldn’t get air to move freely through her lungs. When she arrived she was blue, and her mother and father were quickly ushered to the adjacent relatives room. We’d work to save their daughter with just a thin partition wall separating us. Anaesthetic gases can often relax the lungs, but with her they made no difference. We tried infusing drugs to widen her airways; tubes of high-flow oxygen; paralysing her muscles – but everything failed. Within minutes her heart began to beat erratically. All the clinicians were frantic, unable to accept that such a young woman might be about to die. We moved around her in a blur, glancing hurriedly up to a screen where her heartbeats began to broaden, then finally weaken.

She lost her pulse. My recollection of the next thirty minutes is hazy: adrenaline injections, chest compressions, atropine to quicken the heart’s muscle. Twice her heart went into spasms of chaotic electrical activity and had to be shocked with the defibrillator, and after the second of these, her pulse restarted. Jubilation was followed by an evolving sense of horror: her heart might have restarted but her pupils no longer responded to light. She had regained a pulse, but had suffered severe brain damage. I phoned the closest city hospital, and its intensive care team made arrangements to come and get her.

Her parents were young themselves; must have been almost teenagers when she’d been born. I sat down, grey-faced, and explained with as much tact and as much truth as I could that her heart had stopped, had been restarted, but that her brain was no longer working properly. I told them she’d be transferred to intensive care, and they could travel with her. I can’t remember the details of what I said, but when her father managed to reply, the spontaneous and transcendent generosity of what he said astonished me: ‘If she doesn’t come back, do you think she can help others?’ he asked. ‘Do you think she could donate her kidneys?’

She didn’t recover in the intensive care unit, and after twenty-four hours or so, she was ‘transplanted’. Her kidneys went to two different adults, at opposite ends of the country. Her corneas gave sight to someone who’d been blinded. Her liver went to a reformed alcoholic. Her pancreas and small intestine went to a teenage boy who suffered a rare genetic condition that meant he couldn’t absorb food. Of her major organs only her heart and lungs – which had brought her to the gateway of death – and her brain – which had travelled too far into darkness to make it back to the light – were buried with her.

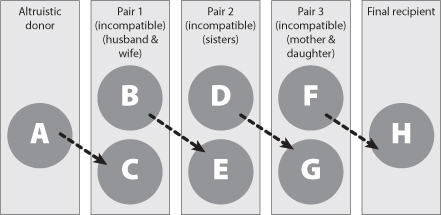

KIDNEY TRANSPLANT IS UNIQUE in that, because we have two, a single kidney can be donated in life with only relatively minor inconvenience on behalf of the donor. In the past these transfers of kidneys were for the most part between siblings, parents and children, but this need no longer be the case. Advances in tissue typing can match compatible organs across huge populations, and the acceptance of transplantation as a social good has meant more donations between individuals who are not blood relatives. These ‘live unrelated donors’ now constitute around half of all kidney transplant operations in the West, and occur between strangers. Since 2011 in the UK there has been a system of ‘pooled donation’ whereby someone can donate a kidney to an unrelated and unknown individual, and then others can donate in a gift circle that can be as wide as there are participants that can be lined up. Computers match compatible individuals.

B might want to give his kidney to his wife C, but as she’s incompatible with him, she needs to receive one from A. Because his wife is receiving a kidney, B can choose to donate his instead to E. E’s sister (D) donates one to G, and G’s mother (F) donates one to H, and so on. It just takes one altruistic donor to start off the gift circle – in this case A – someone who donates a kidney to a stranger with no expectation of benefit to themselves.

DAVID MCDOWALL is part of this new trend in sourcing kidneys for transplant in the West – the gift circle that can be started through an altruistic donation. We met through mutual friends at a time when he was recovering from the surgery. ‘I was simply trading in a spare body part someone else can make good use of,’ he told me. ‘It wasn’t much of an inconvenience for me, but could be a lifesaver for someone else.’

David never met the person who now carries his kidney, and because of the strict legislation around organ donation in the UK he never will. ‘The risk of going through the operation was tiny, and besides, what is the point of a risk-free life?’ David is a scholar and historian now in his sixties, who specialises in the Middle East. ‘I have had far closer brushes with death working in Lebanon,’ he said.

David had been thinking about donating one of his kidneys ever since he read an article in a newspaper about the possibility of making such a gift. Several years earlier he’d been close to death with a bleeding stomach ulcer, and would have died without transfusions. Donation was for him a fitting way to return a gift to the system that has saved his own life (blood transfusions are unpaid in the UK – historically a far more usual way of donating body tissue). When his grandson was born with a life-threatening condition requiring surgery, six weeks of intensive care and several months of hospital recovery afterwards, he felt the push to commit to going ahead. ‘By then I knew I must do it,’ he said. ‘It was a sort of thanksgiving – even if my grandson had died I would still have done it, as the decision to donate had already been made. Having said that, I was acutely conscious of all that the health services had done.’ He wrote to Hammersmith Hospital in London, offering to give them one of his kidneys, and just over a year later he was on the operating table.

I told him that I’d heard of some people, particularly if they’d been paid for their kidneys, being unhappy later about the decision – they’d found the experience more frightening and more painful than they’d anticipated. ‘That wasn’t my experience at all,’ he said, ‘the main difficulty, at first, was simply turning over in bed because of the discomfort of the scar, but that passed very quickly.’ He’d had the operation at 9 a.m., and by that same evening had taken his first steps out of bed. ‘Some intelligent doctor explained that the sooner I was walking the sooner I’d be out of hospital,’ he said, ‘so the following day I walked and walked and walked, clutching the stand with the drip. I was moved to an ordinary ward – had a very sleepless night – and they let me go the following day.’ He’d been in hospital just over forty-eight hours.

‘Are you curious about who has your kidney now?’ I asked him.

‘Of course!’ he said, ‘But I understand why they mustn’t tell me. I’d hate for anyone to feel uncomfortable, or under any sort of obligation.’ He became thoughtful. ‘When I’m walking the city streets the knowledge that I may be passing someone carrying it, that I could even meet him or her and never know, is a delight.’

IN EUROPE IT’S COMMON to place stones on high ground in acts of commemoration, but in Tibet the hilltop memorials are more explicit. The traditional method of body disposal there is ‘sky burial’: the bodies of the dead are broken into pieces and left on a mountainside for vultures. It’s a convenient way of disposal where the soil is too thin to dig graves, and a way of acknowledging that it’s only through the deaths of living things that other lives are sustained. The soil around sky burial sites is littered with human bones, which remind travellers of the impermanence of all things.

Just as Europeans create cairns to guide travellers, Tibetans build piles of stones along traditional pilgrimage routes. These routes are like meridians over the landscape; as pilgrims move along the paths they carry stones from one pile to another. As the circling of special stones over the sick can be seen in Tibetan medicine as a way to a kind of healing of the body, so the circling of stones over the landscape, carried in the hands and pockets of pilgrims, can be seen as a way to healing of the spirit.

Healing stones aren’t exclusive to Tibet: in the town of Killin in Scotland there are a collection of eight stones held sacred to St Fillan, a Celtic divine thought to have been active in the eighth century. The tradition holds that you take the stone that most resembles your own afflicted organ, and rub it on your body. Visitors can go to the old mill in Killin, the first of which is said to have been established by the saint, and take the stones in hand. One looks like a face, one is marked like ribs, and another has an umbilicus like a belly. There’s one that is dark and particularly smooth, and resembles a human kidney.

The poet and artist Alec Finlay has an interest in these sacred stones, and has combined it with his fascination with transplant surgery. He was commissioned by the government in Scotland to create a national memorial ‘for organ and tissue donors’, in the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh. He built a traditional taigh, a Gaelic turf-roofed house, such as those found in the high country of Scotland – constructions which once offered shelter for pilgrims, herders and hermits. Visiting it, I was reminded of the Buddhist cairns and mountainous uplands of Tibet. Taighs weren’t always built for shelter: there are some that were built for ritual and to house sacred stones.

‘I felt that the memorial needed to make manifest qualities of inwardness and shelter,’ Finlay wrote. ‘I wanted there to be some kind of a protective dwelling for the feelings of those who were grieving … a chamber for the memory of the dead, but, being in a garden, it could gather a sense of floral growth and light.’

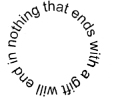

In the roof of his taigh Finlay laid a series of stones, inspired by those in Killin, representing gifts of organs from the dead to the living, but also donations from the living so that others’ lives were eased. On the floor of the structure there was a hollow cut into stone, as smooth and concave as a baptismal font, and around it a simple, nine-word poem engraved in a ring, repeating itself endlessly:

Finlay’s intention was to celebrate remembrance and sanctity, and explore ways in which the body and its memories can be embedded in a landscape. But he also wanted the memorial to acknowledge that transplant is a new phenomenon, rendered possible only through high-tech advances in medical science: ‘There is no curative treatment that is closer to being a secular miracle,’ he said of transplant surgery – a miracle wrought through medical and surgical expertise rather than faith in the healing power of stones. Into the roof of the taigh, above ground, he had placed stones symbolic of transplanted organs, but under the taigh he buried a wooden chest, representative of the dead that have become donors, to acknowledge that what is most meaningful is often out of sight. Into the lid of the buried chest he secured a surgeon’s scalpel and a packet of the medication used to prevent rejection of the transplanted organ.

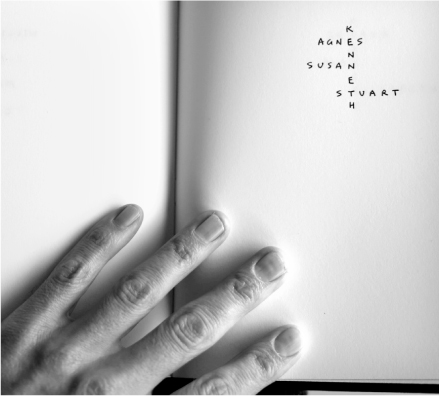

To preserve anonymity, and emphasise how much we hold in common, Finlay hand-wrote the first names of every organ donor in Scotland in a book, interlinking each name to the others through a series of woven poems. The memorial in the botanical garden acknowledged the physical landscape around us – mountains and forests, cairns and sky burials – but also the social landscape of human connections to which we are bound.

Footnote

1 The transplantation of skin had already demonstrated to surgeons that the transfer of tissue between identical twins was tolerated without ‘rejection’ by the recipient.