chapter 10

Hardship and Resurgence

Throughout the 1920s, many unions were destroyed (in some cases through open warfare, as depicted in Matewan, John Sayles’s powerful film about the assault on West Virginia mineworkers). Employers continued to be nervous, however, about the possibility that their workers would join the AFL, the IWW, or one of the Socialist or Communist parties. The Russian Revolution had proved popular not only in Germany, Austria, and Hungary, where workers had attempted their own revolutions, but also among energetic clusters of American workers (some influenced by the deep labor-radical subculture in the United States, others influenced by the revolutionary currents in what had been their native lands before immigrating to the United States).

Employer Triumphs

Largely in response to this undercurrent of radicalism and the more general threat of unionization, U.S. industrialists such as Henry Ford further developed innovative production and managerial techniques—begun several years earlier—to keep employees under their control. In one and the same year (1914) Ford had pioneered in (1) an assembly-line technology, the endless chain conveyor, helping to produce a standardized, low-cost automobile, and in (2) the strategy of paying dramatically higher wages than usual ($5 a day) to thwart a unionization drive by the IWW—also increasing workers’ purchasing power so that they could more easily afford such consumer goods as his cars. Such innovations—called “Fordism” by some theorists—were part of the general trend by businessmen to secure their control of the workplace. The intensified wear-and-tear on his assembly-line labor force led to spectacular increases in productivity, so that by 1925 almost as many Ford autos were produced in a single day as had been produced by Ford’s company during the entire year of 1908. Such growth in the mass-production industries enabled employers like Ford to develop elaborate company welfare programs in the 1920s that included modest insurance and pension plans—which were designed to create employees that would conform to the company’s paternalistic vision of loyalty on the job and a proper home life.

A powerful coalition of employers launched the so-called American Plan which, throughout the 1920s, successfully blocked or destroyed independent unions and secured business’s far-reaching control of the workforce. On the one hand, this involved an extensive propaganda campaign against any independent labor movement as “un-American,” using authoritarian methods (stool pigeons, intimidation, and repression) in the workplace to crush any efforts to organize unions. In many cases workers were forced to sign a “yellow-dog contract” promising never to join a trade union. At the same time, company-controlled grievance procedures (in some cases even company unions) were combined with paternalistic company welfare plans, “profit-sharing” schemes, and company-sponsored social activities to make employees loyal to and dependent on their benevolent bosses. Given the prosperous business climate of the 1920s, this carrot-and-stick strategy of “welfare capitalism” would prove highly effective. Union membership declined from 5 million in 1920 to 3.5 million in 1923.

Firms with welfare capitalist policies also maintained extensive spy systems, and they blacklisted “reds” and unionists. Coal camps and textile or steel towns had private police forces that maintained tight control. But even in “normal” towns and cities, employers were regularly able to get judges to issue injunctions to protect them from unions and strikes. An injunction is a legal order restraining a person or group from actions which might cause damage to someone’s life or well-being or property. Union organizing efforts and strikes often were broadly interpreted as damaging the business of the employer. The outlook of many judges was expressed by the Supreme Court justice who commented that while “picketing may hardly be termed a manly occupation,” there are still “some people, both men and women, [who] choose to do it and get some thrill out of it. Just why, or how, no man can say.”

Louis Goldberg and Eleanore Levenson described what often occurred in the 1920s and early 1930s:

The court issues an order forbidding picketing. [The trade union member] can no longer talk to his fellow men to persuade them to support the strike. He cannot publish in the press or through circulars that he has a grievance against the employer. He is not allowed to hold public meetings. . . . The injunction frequently goes so far as to prohibit the union from paying strike benefits and the officials from carrying on their usual duties.

More than this, it was common that “the striker in the street finds a hostile and brutal attitude on the part of the police rarely exhibited toward glamorous racketeers.” This was often supplemented by the employer with his own strong-arm men, sometimes a “security” force made available from private detective agencies or other organizations specializing in strikebreaking. And a predominantly anti-union press (owned by, and largely financed with advertising from, big-business interests) sought to persuade its readers that such judges, police, and thugs were acting in the public interest.

Here and there, modest gains were made by labor activists. One of the most impressive came through the efforts of A. Philip Randolph to organize African American railroad employees (excluded from most railroad occupations that were well organized by segregated, all-white unions) into the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters—but such successes were unusual in the 1920s. Randolph was a radical visionary, a veteran of the socialist movement, representing an approach not shared by most of the AFL officeholders. By the end of the decade the AFL, now led by William Green (even less combative than the late Sam Gompers), was more cautious and pessimistic than ever about the possibility—or in some cases the desirability—of organizing the masses of unskilled workers.

Related to this was another problem seriously undermining trade unionism. “In the days when the unions still possessed some militancy the conditions of organized workers always stood forth clearly as being far better than those of unorganized workers,” commented William Z. Foster in a 1927 publication of the Trade Union Educational League. “But now in many cases union workers are employed under conditions little if any better than those of non-union workers. This is a deadly situation.” He blamed the dominant trade-union leaders who concentrated on avoiding strikes, seeking a “higher strategy of labor” that involved cooperation with employers, and seeking to maintain a passive union membership that would not make trouble. Such labor “misleaders,” he concluded, “do nothing to stir the militant spirit and class enthusiasm of the workers,” even though “the great mass of workers, both organized and unorganized, live in hardship.”

There was much truth in Foster’s criticism. Although the 1920s are generally seen as a period of general economic prosperity—and business was certainly doing very well—it has been estimated that about 40 percent of the population lived at or below the poverty line. Things were about to get much worse.

Economic Collapse

The ten-year Great Depression hit in 1929, in part generated by the low wages of workers, who couldn’t afford to buy what they made. The “welfare” paternalism of most companies collapsed, giving way to a resurgent “get-tough” policy. Troublemakers were fired or beaten up. Ford and other employers sought greater economic efficiency through the “speedup” of production. Fear stalked every worker. As the speedup intensified, forty was considered too old to work. Older workers dyed their hair in order to hold onto their jobs. By 1931, unemployment was massive. At one point, U.S. Steel didn’t have a single full-time production worker—everyone was working one or two shifts a month. The company gave out baskets of food to keep its workforce off public welfare (workers who went on welfare were fired) and the costs of food baskets were deducted from workers’ pay.

The devastating impact of the Depression, in human terms, is suggested when even the president of the United States asserted that one-third of the nation was ill-fed, ill-clothed, and ill-housed. It is also partly captured by photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, Ben Shahn, and Walker Evans (in the great tradition of Lewis Hine earlier in the century and Earl Dotter in later years). A similar imagery comes through in the classic film Grapes of Wrath, based on John Steinbeck’s novel of the same name. Such experience had a powerful impact on working-class consciousness.

By the 1930s, labor radicals could point to forty years of failure by the mainstream unions in organizing basic industries. Auto factories, refineries, and modern steel mills were inhospitable to craft unions because most employees weren’t highly skilled. Employers also made sure to hire workers who were from different countries and different races to foster divisions. Workers were afraid, and for good reason, of the company blacklist and the goon’s blackjack. The harsh realities of the Great Depression seemingly made the problems faced by union organizers even greater. Organized labor had almost never included much more than 10 percent of the U.S. workforce—but in 1930 it represented less than 7 percent, about half the size of its high point ten years before. The leadership of the American Federation of Labor certainly had no hopes of organizing unorganized workers who could easily be competing with unemployed workers for a diminishing number of jobs.

Rose Pesotta, a full-time organizer for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, complained of union officers who served as little more than “chair warmers and cigar-smokers.” Finding that such union “leaders” were inclined to conduct strikes by putting a single paid picketer in front of the workplace in question, and that “rank-and-file members were not encouraged to hang around the union offices,” she observed that even local union meetings were inhospitable to most workers: “The officers would take up routine matters—reading of the local’s minutes, Central Labor Council minutes, the local’s correspondence, then adjournment. Dull proceedings, no new faces.” But the heart and soul of real trade unions, this idealistic anarchist insisted, and the only hope for a revitalized labor movement, were “a legion of men and women unheralded and unsung, rank-and-file people with natural ingenuity, strong working-class loyalty, readiness to sacrifice for an ideal, and all-around unselfishness.”

Labor Upsurge

While the majority of AFL leaders had all but given up on factory workers, there were growing numbers of such workers who hadn’t given up on unions. Many believed that unions, if only they might be established, could simply help them overcome on-the-job abuses and low pay, although in the face of the obvious crisis of the capitalist economy some also shared the radical sentiments of African American poet Langston Hughes:

The bees work.

Their work is taken from them.

We are like the bees—

But it won’t last

Forever.

Here and there were campaigns to rebuild unions. While most of the efforts failed, what workers learned in these struggles gave them useful experience. The IWW was largely destroyed, but here and there (as in auto) some Wobblies kept at it. Some ex-Wobblies had joined the Communist Party, which in the early 1930s had formed its own ultra-left union federation—the Trade Union Unity League—that nonetheless gave some workers organizational experience.

Socialists of various stripes joined together with some unions to form the Brookwood Labor College in New York State, headed by radical minister A. J. Muste, which trained working-class activists in the basics of history, economics, sociology, writing skills, and basic organizing techniques. As James Maurer, a longtime leader of the Pennsylvania Federation of Labor, Socialist, and Brookwood supporter, noted: “My lifelong association with working people in the city and on the farm, skilled and unskilled, organized and unorganized, has taught me that their greatest weakness is lack of knowledge concerning their existence, and this long ago turned my thoughts to workers’ education.” In addition to Brookwood, labor-supported institutions that tried to rectify this situation included Work People’s College in Minnesota, Commonwealth College in Arkansas, Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, and the Bryn-Mawr Summer School for Women Workers. Labor education was also carried on by education departments in a few unions (such as the International Ladies Garment Workers Union and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America), by the Communist and Socialist parties (for example, in New York City’s Workers School and Rand School, respectively), as well as by the far more moderate Wisconsin School for Workers affiliated with the University of Wisconsin (and influenced by such scholarly advocates of “pure and simple” unionism as Selig Perlman).

There were also Unemployed Councils, Unemployed Leagues, and locals of the Workers Alliance mobilizing those who were out-of-work to struggle for government assistance, housing for the unemployed, etc. These and other efforts as labor journalist Art Preis later noted, “trained hundreds of thousands of workers in labor organization and class-struggle tactics.” This helped prepare the groundwork for a new upsurge in basic industry that would change the face of the labor movement and of U.S. society as a whole.

By the early 1930s, militancy was on the rise. In 1934, there were signs that workers could win if they had capable leaders. In Minneapolis, Vincent Raymond Dunne and other dissident-Communist followers of Leon Trotsky (who opposed the Stalin dictatorship that had taken over in the decade following the Russian Revolution) led thousands of teamsters and others to victory through a militant general strike that used bold new tactics such as roving pickets utilizing automobiles and directed via radio. In San Francisco, mainstream Communists allied with Harry Bridges led West Coast longshoremen to a partial victory after a hard-fought general strike. In Ohio, Toledo Auto-Lite workers, led by A. J. Muste and his socialist followers in the American Workers Party, won a similar victory. Big membership gains were also made through organizing efforts by mineworkers, garment workers, and clothing workers.

There were also some painful defeats. Without effective leadership and organization, workers’ militancy failed to build unions. The United Textile Workers—with minimal strike funds and an overly optimistic expectation of support from the reform-minded administration of the newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt—called a nationwide strike, with especially large numbers of union members in the Southern states. (The Democratic President was not inclined to alienate the anti-union and racist political forces in that region—the so-called Dixiecrats—that were an important component of his own party.) One Southern employer had commented: “I don’t care if any of my workers join a union—just so they don’t tell me about it.” Employers saw the strike as a war in which they mobilized far more resources than the union was able to employ: martial law, the National Guard, goon squads and gun thugs, Pinkerton spies, as well as antiunion newspapers and radio stations. Sixteen workers were killed and many more were wounded, the strike was crushed, and 15,000 strikers were blacklisted. The cause of labor in the South was set back for many years to come.

Yet the balance of power in the labor struggles of 1934 had tilted decisively in labor’s favor. And the leaders of the victorious labor insurgencies tended to be deeply rooted in their communities, with strong ties to their coworkers, and at the same time animated by fiercely radical ideas. “Our policy was to organize and build strong unions so workers could have something to say about their own lives and assist in changing the present order into a socialist society,” V. R. Dunne matter-of-factly explained of his efforts in leading workers of his hometown to victory. “Probably four or five hundred workers in Minneapolis knew ‘Ray’ personally,” journalist Charles Walker later commented. “They formed their own opinions—that he was honest, intelligent, and selfless, and a damn good organizer for the truck drivers’ union to have. They had always known him to be a Red; that was no news.” On the West Coast, Harry Bridges, leader of the radicalized International Longshore and Warehouseman’s Union, did not hesitate in expressing the opinion that “the capitalistic form of society . . . means the exploitation of a lot of people for a profit and a complete disregard of their interests for that profit, [and] I haven’t much use for that.” Many of his members saw things the same way. The established labor leadership felt new pressures and a new vulnerability from below.

CIO and Labor Radicalism

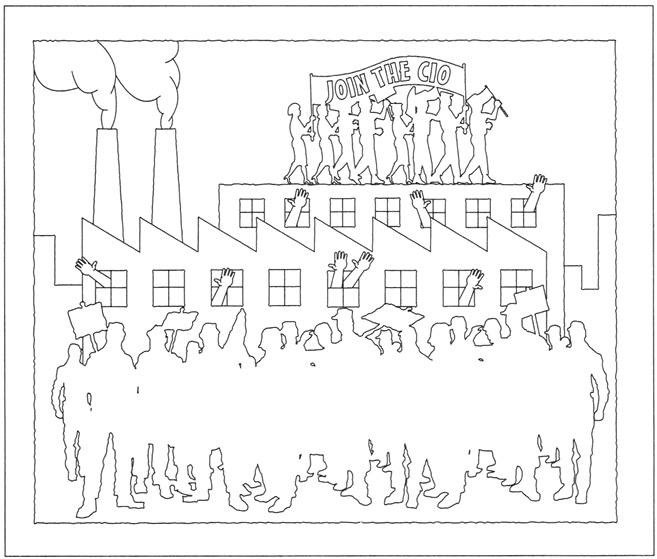

The rapid rise of left-led unions, mass strikes, and rank-and-file workers’ movements inspired workers throughout the country, and also generated ferment within the AFL. John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers, David Dubinsky of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, Sidney Hillman of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, Charles Howard of the International Typographical Union, and others urged the Federation to launch an organizing drive among the country’s mass-production workers, and to form unions along industrial rather than craft lines. In 1935 they formed a Committee for Industrial Organization within the AFL, which resulted in their expulsion from the AFL by late 1936. Despite bitter AFL denunciations of them as apostles of “dual unionism” (with which the IWW had been tagged in earlier years), CIO organizers and activists continued to surge forward throughout 1937, and in the following year they formally established the Congress of Industrial Organizations. Lewis emphasized the existence—currently outside the ranks of organized labor—of “a great reservoir of workers here numbering millions and millions of men and women, and back of them stand great numbers of millions of dependents,” who wanted “a policy that will permit them to join with us in this great fight for the maintenance of the rights of workers and for the upholding of the standards of modem democracy.”

The trademark of the CIO seemed to be the stern visage and militant, biblical oratory of John L. Lewis. His reputation in the labor movement for conservatism and running a top-down union regime were balanced by his clear understanding that workers were ready to organize and that new tactics were needed. The scourge of labor radicals within his own union for decades, he proved quite willing to work closely with many whom he had bitterly fought in earlier years. Such was the case with John Brophy, expelled from the UMW for opposing Lewis with a left-wing “Save the Union” movement in the 1920s but taken back into the UMW in the early 1930s and appointed CIO director of organization in 1935. Lewis’s own powerful rhetoric tilted leftward in the new situation.

Blaming the Depression and the decline of workers’ quality of life on industrial policies “determined by a small, inner group of New York bankers and financiers,” Lewis emphasized that “organized labor has determined that this sinister financial and industrial dictatorship must be destroyed.” This was to be accomplished through the efforts of inclusive new industrial unions that would establish “genuine collective bargaining” with the big corporations, and also through political organization “by the labor groups, whether hand or brain workers, to the end that it may be used in cooperation with other unselfish groups of our people in establishing sound measures of industrial democracy, and in bringing about other social, economic, and humanitarian reforms which are traditionally and indissolubly associated with the ideals and aspirations of our self-governing republic.”

In early 1936 rubber workers seized control of the Goodyear plant in Akron, Ohio with a sit-down strike and quick victory that established the United Rubber Workers of America as the first CIO success story. CIO resources and staff moved in to assist local Socialists and Trotskyists “who had been at the hub of Akron’s organizing campaigns,” as the noted labor writer Sidney Lens later commented. Communists and other radicals were in the forefront of the tough-fought union victories in the summer and fall of 1936 over General Electric and the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) that put the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America on the map as another CIO triumph.

In the auto industry, too, the CIO succeeded because of a rank-and-file upsurge. In Flint, Michigan, workers staged a sit-down strike that lasted several weeks and shut down much of General Motors Corporation’s production—resulting in a resounding victory for the newly formed United Automobile Workers of America. U.S. Steel sought to avoid such turmoil and signed a national agreement with the CIO’s Steel Workers Organizing Committee even though the union’s base among steelworkers was relatively weak. Another large company, Jones and Laughlin, agreed to a union election after a brief strike. In order to enforce contracts, the early CIO relied on workers’ own solidarity. Shop stewards collected dues directly from workers, and union leaders had to address grievances immediately. Workers resolved shopfloor problems by engaging in short “quickie” strikes or slow downs. On an assembly line or in a modern mill or refinery, even a small group of workers could cripple production. Just as the Wobblies had preached, these tactics inflicted maximum pain on employers with minimum risk to workers. The UAW rank-and-file also showed a preference for tough and experienced organizers with left-wing backgrounds, such as Walter, Victor, and Roy Reuther; Wyndham Mortimer; Robert Travis; Emil Mazey; and a host of energetic activists.

Among these were Genora Johnson Dollinger and others who organized the colorful “Women’s Emergency Brigade” (depicted in the stirring documentary film With Babies and Banners) that played a key role in winning the Flint strike. The Brigade evolved out of the UAW’s Women’s Auxiliary. “The core group decided that whereas all of the other AFL auxiliaries were called Ladies Auxiliaries and they had their box socials and little parties and things like that, but didn’t really know anything about labor or conditions in the country,” Dollinger later recalled, “we decided we were women and we didn’t want any of this lady stuff, so we called ourselves for the first time in the American labor movement the Women’s Auxiliary of the UAW.” Although some of the union men “remained just as chauvinistic as ever,” others “who were really union men and were much more open to having the forces to build a union and win a strike were very grateful and told us many times how happy they were in their homes since their wives got active.” The women who were involved “were changing almost day by day . . . standing a little taller and talking to the men a little more sure of themselves.” Such female militants inspired radical songwriter Woody Guthrie—part of a group of radical union troubadours known as The Almanac Singers—to write the famous song “Union Maid”:

There once was a union maid who never was afraid

of goons and ginks and company finks

And the deputy sheriffs who made the raid;

She went to the union hall when a meeting it was called,

And when the company boys came ’round

She always stood her ground.

Oh, you can’t scare me, I’m sticking to the union.

I’m sticking to the union, I’m sticking to the union.

Oh, you can’t scare me, I’m sticking to the union.

I’m sticking to the union till the day I die.*

Such changing attitudes were largely a result of radicals’ efforts. Dollinger was herself a member of the Socialist Party at that time (and later a Trotskyist). In an interview in the 1990s, she still emphasized the importance of left-wing influence in helping build a consciousness vital for strengthening the union struggles:

It happened that the headquarters for the Socialist Party, the Proletarian Party, and the Socialist Labor Party were all in the same big historic building where the union offices were on one floor. It was an old, rickety building but it was something we could afford. And workers were coming up to find out what could be done and we would get to know them. We gave classes in labor history to let them know that there were gains that had been made and that there were labor leaders who had given their lives for the organization of labor.

Although many of the new CIO officers and members could hardly be considered political radicals, in a number of the new unions, various Socialists, Communists, and Trotskyists assumed key roles as selfless organizers and respected leaders.

The radical fervor also found reflection in its understanding of the necessity to overcome racial divisions. The new labor federation asserted that “the CIO pledges itself to uncompromising opposition to any form of discrimination, whether political or economic, based on race, color, creed, or nationality.” While shortcomings could certainly be found in how this sentiment was implemented, the country’s leading African American newspaper, the Pittsburgh Courier, remarked that “the only real effort that has been made to let down the color bars since the days of the Knights of Labor is that of the Congress of Industrial Organizations.” The NAACP’s chief legal advisor, Thurgood Marshall, concurred: “The program of the CIO has become a Bill of Rights for Negro labor in America.”

Editor of the CIO News Len DeCaux has described the early CIO as not simply a new labor federation but as “a mass movement with a message, revivalistic in fervor, militant in mood, joined together by class solidarity.” On Labor Day 1937, CIO chieftain John L. Lewis, in order to express the CIO message, intoned: “This movement of labor will go on until there is a more equitable and just distribution of our national wealth. This movement will go on until the social order is reconstructed on a basis that will be fair, decent, and honest. This movement will go on until the guarantees of the Declaration of Independence and of the Constitution are enjoyed by all the people, and not by a privileged few.” Writing in 1938, labor journalist Mary Heaton Vorse commented: “Labor has shown in its struggles an inventiveness, intelligence, and power greater than anything before in its long history. Whole communities of workers have been transformed.” Looking back on this period, DeCaux elaborated:

As it gained momentum, this movement brought with it new political attitudes—toward the corporations, toward police and troops, toward local, state, national government. Now we’re a movement, many workers asked, why can’t we move on to more and more? Today we’ve forced almighty General Motors to terms by sitting down and defying all the powers at its command, why can’t we go on tomorrow, with our numbers, our solidarity, our determination, to transform city and state, the Washington government itself? Why can’t we go on to create a new society with the workers on top, to end age-old injustices, to banish poverty and war.

The New Deal

The labor upsurge and radicalization created a remarkable change in the country’s political climate. In 1932, the Norris-LaGuardia Act had already outlawed the “yellow-dog contract” and deprived federal courts of the power to issue the sweeping anti-union injunctions (against union activity, strikes, picketing, etc.) that had been so common in previous decades. In the same year, Democratic Presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt had been swept into office promising Depression-ridden America a “New Deal.” The first term of his administration seemed to balance pro-business and pro-labor policies in a somewhat dubious National Recovery Act which was declared unconstitutional but which (while it lasted) gave workers the right to organize unions by federal law. By 1936, under the impact of the early CIO gains and radical working-class pressure, Roosevelt’s New Deal tilted in a much more pro-labor direction. The President denounced as “economic royalists” those conservative businessmen who vociferously objected to his programs—while at the same time explaining that he was doing all this to save capitalism, which some of the more sophisticated corporate executives understood quite clearly.

Nonetheless, the sweeping package of New Deal social reforms went far beyond any government programs even of the pre–World War I Progressive era—creating Social Security, public works projects, unemployment insurance, and much more that was beneficial to U.S. working people. One of the most far-reaching pieces of legislation was the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, commonly known as the Wagner Act, which established the collective bargaining framework that defines today’s labor unions. In sharp contrast to the past, unions no longer built organizations that negotiated with employers based on the sheer strength of skill or solidarity, but could rely on government-monitored elections (through the National Labor Relations Board) to win recognition. Workplace grievances didn’t have to result in strikes, but could be arbitrated through a special court system, and rulings had the force of law.

Some analysts have argued that unions’ reliance on the government’s labor-relations system played a major role in undermining labor’s radicalism and independence. Union leaderships were, more often than not, inclined to rely on the lengthy arbitration process rather than the often quicker and more decisive resort to local strike action. Government regulations were designed to thwart rank-and-file militancy, and unions found that attempts to buck the new labor relations system could result in the loss of the very real protections and advantages provided by the NLRB and other aspects of the Wagner Act. Once contracts were signed, union officials were generally expected to enforce the contract with their members—accepting the employer’s authority at the workplace, preventing “wildcat” and “quickie” strikes, enforcing discipline. The fact remained that immense gains were made by organized labor under the Wagner Act.

The ranks of the CIO were swelled by new industrial unions in steel, electrical, auto, longshore, maritime, transit, rubber, textile, and more. Soon the AFL moved in a similar direction to maintain its own survival. Some AFL unions, such as the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, were transformed from craft organizations into mass-industrial unions (in this case thanks to the influence of the Minneapolis Trotskyists—the Dunne brothers, Carl Skoglund, Farrell Dobbs, and others) with considerable idealism and enthusiastic response from a broad range of workers. The AFL’s Amalgamated Meatcutters and Butcher Workmen led by Socialist Pat Gorman also embraced industrial unionism, reaching out to workers of many trades.

But certain other growth-conscious AFL unions concentrated on “organizing the employers” rather than organizing the workers. A. O. Wharton, the anti-leftist (and anti-Semitic) president of the AFL International Association of Machinists, sent out a letter to his staff in 1937 indicating that many employers would strongly prefer to deal with a conservative AFL organization than with the radical-tainted CIO. “Since the Supreme Court decision upholding the Wagner Labor Act, many employers now realize that it is the Law of our Country and they are prepared to deal with labor organizations,” Wharton wrote. “These employers have expressed a preference to deal with AFL organizations rather than Lewis, Hillman, Dubinsky, Howard and that gang of sluggers, communists, radicals and soapbox artists, professional bums, expelled members of labor unions, outright scabs and the Jewish organizations with all their red affiliates.”** Sidney Lens has commented that in the late 1930s and 1940s “hundreds of thousands of workers were dragooned into the AFL; many, if not most, without being consulted and against their will.” Nonetheless, the rivalry with the CIO often forced AFL organizations to push for improved wages and working conditions, and the swelling of labor’s ranks was changing the balance of power within the United States.

Another significant force—influenced by the anarchist-pacifist Catholic Worker movement of Dorothy Day—emerged within “the rough-and-tumble world,” as historian Mel Piehl put it, “where unreconstructed employers, union toughs, Communists, gangsters, and labor priests waged battle for the allegiance of workers.” This was the Association of Catholic Trade Unionists (ACTU), which enthusiastically threw itself into helping to build the industrial unions of the CIO, believing that “side by side with these unions must be Catholic associations which aim at giving their members moral and religious training.” An aspect of the ACTU’s ideology was expressed by one of its architects, John Cort, who envisioned a future when “workers who are capable of creative effort once again become ‘workers’ in the true sense, and no longer the unthinking slaves of machinery and stockholders. Then industrial democracy will reign not only in each plant and company, but throughout the national economy.” Industrial unionism could lead the way against “greed and profiteering” toward guaranteeing “a living wage” for all, eventually—as Piehl put it—creating a future when “capitalism might be gradually transformed into the humane and Christian economic order envisioned by the popes” in their encyclicals Rerum Novarum (1891) and Quadragesimmo Anno (1931). Through the efforts of activists such as Cort, Martin Wesing, Father Charles Owen Rice, and others, the ACTU helped organize unions, win strikes, push back gangsterism—and also to develop an alternative to Marxist ideas and to challenge the influence of the Communist Party. According to historian of U.S. anti-Communism John Haynes: “Hundreds of workers who had passed through the ACTU’s training sessions in parliamentary procedure, organizing, labor law, bookkeeping, and, of course, Catholic social philosophy and anticommunism, became officials of union locals.”

In 1937 the CIO had 1.5 million members, while the AFL had about 2.5 million; by 1941 the size of both labor federations had almost doubled—and close to one-third of the workforce was unionized. In the Southern states of the former Confederacy, however, where conservative racist regimes had assumed power in the post-Reconstruction era following 1877, the continuing repressive political climate combined with sharp racial divisions within the working class to limit or block the stunning labor victories that swept much of the North and the West. Extreme violence, intimidation, race-baiting, and red-baiting were utilized to smash the efforts of Southern textile workers and others to advance the union cause. Yet enough gains were made by CIO organizers elsewhere to convince many that it would only be a matter of time before the South went the way of the rest of the country.

In contrast to the situation in most industrialized countries, however, the labor movement did not have its own political party. Instead, for the most part, unions in the United States were integrated into the New Deal alliance of the Democratic Party under President Franklin D. Roosevelt (known by his initials “FDR”)—which included many of the conservative Southern politicians who opposed union organizing in their home states. A related problem was that FDR’s primary commitment was not to his working-class supporters—he was no less committed to the interests of big business, which sometimes meant giving labor the short end of the stick. And by the late 1930s, when he was beginning to shift the country to a war footing in preparation for the fast-approaching Second World War, he proved more than willing to jettison many of the New Deal social reforms.

As the newly organized unions solidified at the end of the Depression decade, it became clear that far from destroying capitalism, as many employers had feared, the government’s support for unions had stabilized capitalism. FDR’s balancing act was highlighted in 1937 when strikers at Republic Steel were shot in the back in the Memorial Day Massacre: the President employed the phrase “a plague on both your houses,” equating union victims with the police and the steel thugs who had victimized them. While FDR’s Democratic Party relied on workers’ votes and unions’ organizational muscle, the party never wavered in its support for the “liberty” of corporations and the free-market system. This highlights a difference between the U.S. labor movement and those in Europe, insightfully summarized by historian Lizabeth Cohen:

In Europe, where workers were more anti-capitalist, they supported unions and political parties that demanded more radical changes, helping in some cases . . . to establish welfare states that were more Socialist in orientation, and in others . . . to make workers less integrated into mainstream political parties. American workers, in contrast, even when they harbored a “class” agenda as in the 1930s, turned to an existing mainstream political institution like the Democratic Party to achieve it. As a result, although at the time many individual workers and CIO officials hoped to accomplish working-class objectives through the Democratic Party, the reality of the party’s broad base early on committed it to multiple, and ultimately less progressive, goals.

CIO President John L. Lewis—whose strong personality increasingly clashed with that of Roosevelt—had helped to establish the firm labor-Democratic alliance of the 1930s, but by the end of the decade had come to distrust it, expressing the view that organized labor must preserve a certain amount of political independence. Roosevelt’s “plague on both your houses” comment drew this widely quoted rebuke from the union chieftain: “Labor, like Israel, has many sorrows. Its women weep for their fallen, and they lament for the future of the children of the race. It ill behooves one who has supped at labor’s table and who has been sheltered in labor’s house to curse with equal fervor and fine impartiality both labor and its adversaries when they become locked in deadly embrace.” When Roosevelt announced that he would run for a third term in 1940, Lewis argued that the CIO should not support him.

Some thought the CIO leader might call for the formation of a new labor party—but instead he took the more “pragmatic” stand of backing the liberal Republican candidate, Wendell Wilkie. When the bulk of the CIO did not follow this course, Lewis resigned as president of the CIO. As Roosevelt swept on to a third presidential victory, the nation’s economy was coming out of the Great Depression—not because of the New Deal policies, but because the approaching Second World War (which had already begun in Europe and Asia) was good for U.S. business, which was revitalized by war production.

A new era was about to dawn.

* UNION MAID. Words and Music by Woody Guthrie TRO-©-Copyright 1961 (Renewed) 1963 (Renewed) Ludlow Music, Inc., New York, New York. Used by permission.

** Ironically, half a century later, the president of the International Association of Machinists would articulate precisely the orientation that IAM President Wharton was attacking. “You don’t have to be a Marxist to observe the conflict between labor and capital is as old as the history of the world,” wrote IAM President William Winpisinger in the 1980s. “Each one’s behavior has been remarkably consistent throughout history. Labor always seeks to preserve and improve its material lot, to gain a greater share of the wealth it produces, and to achieve a greater degree of economic and political freedom. Capital is remarkably consistent in its resistance to labor’s quest. Corporate management has always relied on absolute power, authority and control—the ultimate and most ancient order of political supremacy—to achieve its goals of cost minimization, market domination and profit maximization. . . . When labor is militant, history tells us, trade union goals are advanced. . . . ”