chapter 12

Cold War and Social Compact

U.S. corporations did launch a counterattack against what they insisted was excessive union power and against radical labor challenges to “America’s free enterprise system.” Massively financed pro-business propaganda campaigns dovetailed with big contributions to the election campaigns of pro-business Republicans and Democrats—culminating in conservative congressional amendments to the nation’s labor law. The Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 did not outlaw unions outright—public opinion and working-class power would no longer permit that—but rather was designed to moderate and de-radicalize the labor movement. Limitations on picketing, prohibition of secondary strikes and boycotts, the imposition of “cooling-off periods,” and other governmental controls were designed to undercut the natural militancy and organizing techniques that had been so effective in the 1930s and again in 1946.* There was also a ban on direct union contributions to political parties (there were no such restrictions on businesses)—in part to undercut labor support to the Democratic Party, but perhaps in part to hinder the future development of the sort of union-based Labor Party that had recently swept into office in Britain. Another key provision of the Taft-Hartley Act was that union officers could not be members of the Communist Party, and that all labor officials must sign non-Communist affidavits if their organizations were to be granted labor-law protections.

John L. Lewis was one of the few non-Communist union leaders who called for militant action to oppose this and other Taft-Hartley provisions that would “make more difficult the securing of new members for this labor movement, without which our movement will become so possessed of inertia that there is no action and no growth.” Denouncing the act as “bought and paid for by campaign contributions from the industrial and business interests of this country,” he warned the 1947 convention of the AFL: “If you resist the power of the state, the central government will be used against you, and if you don’t resist it will be used against you that much more quickly, because they won’t lose any sleep at night worrying about what to do with a labor movement that is fleeing before the storm.” When the AFL leadership rejected this militant approach (one of its rising stars from the Plumber’s union, George Meany, red-baited Lewis’s record as former head of the CIO), the UMW pulled out of the AFL and remained for years in lofty isolation from both labor federations which had accommodated themselves to the new status quo. (Several years later, Meany himself confessed that union organizing efforts were not nearly as successful as they used to be because, by utilizing the Taft-Hartley Act, “any employer who wants to resist organization and is willing to make his plant a battleground for that resistance can very effectively prevent organization of his employees.”)

Communism and Anti-Communism

The anti-Communist provision of Taft-Hartley—designed to amputate labor’s left wing and intimidate those influenced by radical ideas—was closely related to postwar international developments. The United States had emerged from World War II as the foremost economic, political, and military power on earth, and many business and political leaders confidently predicted that the next hundred years would constitute “the American Century.” On the other hand, they were concerned that the experiences of World War II and popular postwar aspirations would generate revolutions sweeping radical, left-wing, and in some cases Communist regimes into power. This would tear much of the international economy out of the capitalist orbit, with negative consequences for U.S. businesses. Soon a global confrontation crystallized—labeled the “cold war”—between pro-U.S. and pro-capitalist regimes vs. the Soviet Union and countries in Eastern Europe and Asia where Communist regimes had come to power.

In a variety of countries there were many workers and intellectuals, peasants and oppressed people who had high hopes that the Communist movement arising out of the 1917 workers’ revolution in Russia—led by V. I. Lenin and other left-wing Marxists—could lead to a new era of freedom, prosperity, and dignity for all. But the early revolutionary socialist idealism of that movement became increasingly offset by the brutal bureaucratic dictatorship that had crystallized in Russia during the 1920s and 1930s.** Nor were independent trade unions, freedom of expression, or genuinely democratic elections tolerated in the new Communist countries of the late 1940s—facts that were known by many union members in the United States and elsewhere. The Communist dictatorships claimed to be implementing “socialism,” which eventually tainted that term in the minds of millions.

The U.S. government and business community widely criticized such grim realities in massive anti-Communist propaganda campaigns, which were at the same time aggressive public relations efforts for an interpretation of “the American way of life” that emphasized the centrality of corporate capitalism. In its defense of “freedom,” however, U.S. foreign policy warmly embraced and defended unpopular anti-Communist dictatorships in capitalist countries that were friendly to U.S. businesses.

The defense of the corporations’ economic interests abroad was certainly vital to the health of the U.S. business economy. The confrontation with the Soviet Union also generated an arms race and massive military spending that acted as a tremendous economic stimulus. By the late 1950s, Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower felt compelled to warn about the resulting “military-industrial complex” which had created serious distortions in the country’s economic and political life. But in the late 1940s expanded military spending went hand-in-glove with the rise of an extreme anti-Communist campaign within the United States. In the new political climate, conservative politicians tried to reverse some of the social reforms of the New Deal era, and they were joined by liberal politicians in rallying the general public—including the labor movement—behind the pro-business foreign policy objectives.

The unions of both the AFL and CIO had gained a great deal from supporting U.S. foreign policy during World War II. It was clear that support for U.S. cold war policies would also bring benefits, while attempts to buck the tide would be detrimental to unions that had become dependent on a certain amount of governmental benevolence. This posed a problem for the CIO, in which Communists and other left-wing activists had played a significant role from the beginning.

The matter was further complicated by a deep contradiction in the modern Communist movement. Although Communist ideology called for the eventual replacement of capitalism with thoroughgoing rule by the whole working class over the political and economic life of society, the Soviet Union’s dictator Josef Stalin (from the late 1920s to the early 1950s) headed one of the most bureaucratic and murderous tyrannies in human history. Mainstream Communists throughout the world—including their most selfless, effective, idealistic activists in the U.S. labor movement—defended that regime and loyally sought to harmonize their activities with its policies. At times, political consistency and even the interests of the workers were subordinated to Stalinist policy. This made it easier to victimize Communists, and to use the charge of “Communism” to smear or intimidate others who were critical of U.S. foreign policy. The anti-Communist clause in the Taft-Hartley Act was destined to play an important role in splitting the ranks of labor, and in domesticating the initially radical CIO.

The problem was brought to a head in 1948, when some radicals in the labor movement, including Communists, supported the new Progressive Party candidate for President, Henry Wallace. A onetime Vice-President under Franklin D. Roosevelt, Wallace made it clear that he was a firm supporter of the capitalist system—he simply wanted a return to New Deal reformism and an end to cold war policies. But all supporters of Wallace were savagely red-baited in the news media. No less importantly, the bulk of the CIO had committed itself to the re-election of Democrat Harry Truman, and once the elections were over, CIO president Philip Murray launched an attack to drive out the so-called left-led unions that had broken ranks in 1948. In the vanguard of this campaign to “drive the Commies out” was a former Socialist Party activist and the dynamic new president of the UAW, Walter Reuther.

Anti-Communists in the labor movement projected their efforts as a democratic crusade for a form of unionism better suited to advance the real interests of the average worker. Arguing that the CIO could not exist “part trade union dedicated to the ideals and objectives of the trade union movement, and part subservient to a foreign power,” Reuther thundered: “You cannot work with people who are dishonest, who are devoid of the elemental, simple elements of decency and integrity, and these people by their record prove that they are bankrupt morally and that they are not interested in working honestly and sincerely and constructively with other decent trade-union elements.” Some—like the militant Transport Workers Union president “Red” Mike Quill (who had once said, “I’d rather be called a Red by the rats than a rat by the Reds”)—concluded that Communist Party policies “would either wreck the Communist Party within the CIO, or it would wreck the CIO,” and switched over to the anti-Communist crusade so that the CIO, in Quill’s words, “will no longer be run by a goulash of punks, pinks and parasites.” A different view was expressed by James Matles of the “left-led” United Electrical workers. Bitterly commenting that “the cold warriors played a tune and the CIO danced to it, while the house of militant industrial unionism went up in flames,” he lamented that “many leaders of the working class” had chosen to “give up the ghost of class struggle without a whimper” when they got “hooked on the drug of red baiting.”

Forty years later, “labor priest” Monsignor Charles Owen Rice (who had been prominent in the Association of Catholic Trade Unionists and a leading participant in the anti-Communist purge) commented that the Communists in fact “were good organizers technically and in terms of spirit, aggressiveness, and courage. They were, for the most part, on the right side of battles legislative and social” and “were good trade unionists . . . financially honest and dedicated.” In a highly acclaimed history of the CIO, Robert Zieger—hardly uncritical of the Communist trade unionists—summarizes the historical evidence in a similar manner:

The overall record of Communist-influenced unions with respect to collective bargaining, contract content and administration, internal democracy, and honest and effective governance was good. Rank-and-file Communists exhibited a passionate commitment to their conception of social justice. As a group Communists and their close allies were better educated, more articulate, and more class conscious than their counterparts in the CIO. . . . In regard to race and gender the Communist-influenced CIO affiliates stood in the vanguard.

In 1949 and 1950, eleven unions with a combined total of a million members were driven out of the CIO, charged with being Communist-dominated. All but two—the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America (UE) and the International Longshore and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU)—were destroyed in the 1950s and 1960s by a combination of government persecution, employer attacks, media smears, and raids from anti-Communist unions that were happy to pick up already-organized union members. Left-wing workers who remained in CIO unions in auto, transit, maritime, and others, were generally driven from positions of influence, often through brutal factional fights, whether or not they were actually Communists.*** (Years later, the still surviving UE and ILWU had reputations in labor circles for being among the more democratic, effective, inclusive, and socially conscious unions in the country. Some of the positive qualities among the “left-wing” unions were captured in the 1953 film Salt of the Earth—made by blacklisted motion picture employees—which movingly portrays racial and sexual divisions being overcome in a militant strike led by the “left-led” Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers.)

An architect of U.S. labor’s foreign policy was Jay Lovestone, a former leader of the U.S. Communist Party—with a reputation, according to historian John Haynes, of having “considerable intellectual talent and a knack for ruthless factionalism”—who in the 1930s led a left-wing splinter group influential briefly in the UAW and more permanently in the ILGWU. By the late 1940s a de-radicalized Lovestone had gained the full confidence of leaders in the AFL (and, in later years, in the merged AFL-CIO). Describing the entire world Communist movement as consisting of “blind and mechanical followers,” and Communist parties as “primarily para-military outfits organized to execute Kremlin commands,” he warned: “As long as these people or parties remain loyal to the basic aims of Soviet communism or continue to place their faith in the principles of totalitarian communism, they cannot be anything else but apostles of totalitarian dictatorship—instruments of deceit, brutality and aggression.” Lovestone and his closest associates worked with the U.S. State Department and Central Intelligence Agency in efforts to thwart revolutionary, left-wing, and Communist currents in the labor movements of Asia, Africa, and Latin America as well as Europe. Assisting moderate “pure and simple” trade unionists in various countries, Lovestone’s policies were often criticized for helping to create weak unions more effective in transmitting Cold War propaganda than in defending workers’ rights. But for many years to come such policies were not up for debate in U.S. labor’s mainstream. Even some who were still associated with left-wing causes supported the anti-Communist foreign policy. Indeed, the staunchly reformist Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas and other like-minded figures in and around the labor movement, in a public statement explaining their “democratic socialism” in the early 1950s during the Korean War, emphasized their belief that “the outstanding conflict today is between democracy, with all of its human and capitalist imperfections, and totalitarian despotism.”

In fact, by this time distinctly left-wing and labor politics had pretty much dissolved into the liberal wing of the Democratic Party—or, as in the case of the Communists (whose 80,000 membership had melted to a fraction of their former strength), the Trotskyists, and the old IWW, had been marginalized almost to the point of irrelevance on the American political scene.

Labor’s New Balance

The enforced conformity in labor’s ranks resulted in a dramatic decline in the radical fervor and rough-and-tumble internal democracy that had been so vital to U.S. union growth in the 1930s. At the same time, it helped to narrow differences between the AFL and CIO. Since the late 1930s, many had referred to the rivalry between the AFL and CIO as “labor’s civil war.” Yet the split had unleashed the organizing fervor of the CIO and then, ironically, forced the AFL to modernize its own orientation just to catch up. By 1941 the AFL claimed 4.5 million members and the CIO 2.8 million, and in 1948 the AFL had 7.5 million and the CIO close to 6 million (though after the 1949–1950 purges this had dipped to less than 4 million). But in the early 1950s the rivalry—marked by public attacks and raids on each other’s membership—was seen by increasing numbers of union leaders and activists as counterproductive, to say the least.

In 1952 the presidents of both federations, William Green and Philip Murray, had passed away. Ex-plumber George Meany took over as AFL president, and Walter Reuther of the UAW took over the CIO presidency. Meany was a cigar-chomping craft unionist who represented a dyed-in-the-wool “business unionism” far deeper than that of old man Gompers; he boasted: “I never went on strike in my life; I never ran a strike in my life; I never ordered anyone else to run a strike in my life, never had anything to do with a picket-line.” Reuther’s more youthful image was as an ambitious organizer with flair, a modern labor statesman who retained a taste for a more expansive social unionism, and he proclaimed that a unified labor movement would generate “an organization crusade to carry the message of unionism in the dark places of the South, into the vicious company towns, in the textile industry, in the chemical industry.” The two new leaders engineered a merger which was consolidated in 1955, with Meany as president of the AFL-CIO.

Some saw the fusion as subordinating the militant social philosophy of the early CIO to what Transport Workers Union leader Mike Quill called the AFL’s “three Rs—raiding, racketeering and racism.” But Quill’s hostility to AFL conservatism found little support among others. “The CIO had accomplished the work it set out to do, organizing the unorganized in the mass production industries,” commented former CIO organization director John Brophy. “The zeal that the CIO put into its organization campaign energized the AFL and thousands of workers flocked into the old AFL unions as well.” From this standpoint the merger made sense, and it brought together ninety-four affiliated unions with a combined membership of 15 million workers, approximately 36 percent of the labor force.

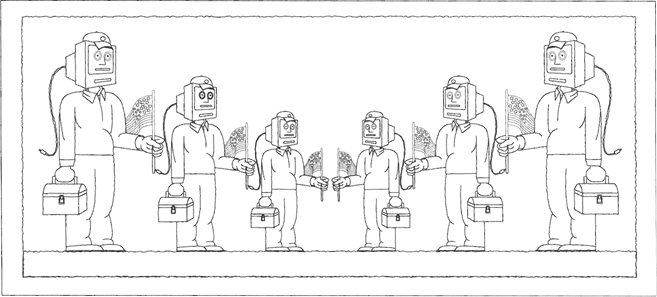

Some observers of the U.S. scene have noted that in the post–World War II period a “social compact” was forged between the three major forces in the economy—Big Business, Big Labor, and Big Government.**** The “bigness” of labor was in the unprecedented size of union membership; the “bigness” of business was in the fact that a small percentage of the population owned colossal wealth and dominated the entire economy; the “bigness” of government involved the greatly expanded social-economic regulating functions and programs initiated by the New Deal, and even more the “military-industrial complex” that mushroomed with World War II and the cold war.

The “social compact” created by these forces meant that business would be free to grow in multiple ways, generating economic prosperity. The government would seek to create global “stability” through a foreign policy beneficial to U.S. business, and domestic “stability” through social programs that would defend U.S. business interests and economic and social security for the bulk of the population. Labor would accept the basic foreign policies of business and government, and the right of private business to own the economy, in exchange for high employment rates, paychecks, and fringe benefits that would yield rising living standards, and social programs that would give security to the young, to the unemployed, and to the elderly. This sense of well-being for many working-class families was enhanced by a market-driven consumerism that provided an increasing quantity of affordable, attractively packaged, alluringly advertised consumer goods to more and more people.

It is by no means the case, however, that businessmen in general embraced even the de-radicalized labor movement of the 1950s. As historian Elizabeth Fones-Wolf has documented, the “full-scale mobilization of business and conservative forces” launched in 1946 continued for decades afterward its sustained efforts to undermine and push back the power and influence of the labor movement through “lobbying, campaign financing, and litigation,” as well as with probusiness propaganda. This included “multimillion dollar public relations campaigns that relied on newspapers, magazines, radio, and later television to reeducate the public in the principles and benefits of the American economic system” in ways that glorified the large corporations while seeking to turn public sympathies against the alleged tyranny of “union bosses” and “government meddling.” But the confrontation of business and the unions did not intensify—which is hardly surprising, considering that conditions in the affluent 1950s did not breed the crusading labor militancy of earlier years.

There were some old-timers, such as John Brophy in the AFL-CIO’s Industrial Union Department, who believed in the need for “democratic planning for the common good,” and who hoped that a unified and growing labor movement would “go forth to challenge the assumption of the business and financial group that they have a vested interest and a privileged position in the operation and management of industry, which they call ‘free enterprise’; to extend our democracy to the economic field and to enhance the lives of the common people”—but such CIO rhetoric was largely the stuff of a bygone era.

“I stand for the profit system; I believe in the profit system. I believe it is a wonderful incentive,” emphasized the AFL-CIO’s new president. “I believe in the free enterprise system completely. I believe in the return on capital investment. I believe in management’s right to manage.” Asking U.S. businessmen “what is there left for us to disagree about,” Meany answered: “It is merely for us to disagree, if you please, as to what share the workers get, what share management gets from the wealth produced by the particular enterprise.” In an era of unprecedented productivity and business prosperity, it seemed clear that all could receive ample portions of the growing economic pie. Generous government social programs could easily be funded by taxing the expanding paychecks of America’s affluent working-class majority. Any grievances at the workplace that remained could surely be ironed out with the help of government-appointed arbitrators, conciliators, and mediators.

As ex-socialist David Dubinsky, president of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, explained: “Trade unionism needs capitalism like a fish needs water.” The new “social compact” would mean, for the first time in history, that a majority of the U.S. working class would have a chance to realize “the American Dream.”

* “The ‘cooling-off’ provisions are in the Act not for the purpose of making labor think twice and encouraging it to find a solution without resorting to a strike,” left-wing labor analyst John Steuben observed. Rather the Taft-Hartley 60-day “cooling-off period” means that, in addition to eliminating the often important element of surprise from strike strategy, “a status quo condition is established for the union while the employers gather every conceivable weapon for use against the proposed strike.”

** This degeneration began during the brutal civil war period of 1918–1921 but was consolidated with the ascendancy of a bureaucratic elite of the Russian Communist Party, headed by the ruthless personality of Josef Stalin, which came into its own after Lenin’s death in 1924, and with the defeat of Trotsky’s Left Opposition in 1927 and of moderate elements around Nikolai Bukharin in 1929. The consolidation of what some referred to as “Stalinism” resulted in repression and death in the Soviet Union for millions of peasants, workers, and intellectuals (including many who believed in the original high ideals of Communism), as well as the erosion of the revolutionary-democratic qualities of Communist Parties throughout the world.

*** For example, one union devised its own loyalty oath which explicitly excluded “members of the Communist Party, the Industrial Workers of the World, or any Trotskyite group.”

**** An astute labor historian, Mark McColloch, has argued that this government-mediated “social compact” can most realistically be seen as the outcome of a stalemate between the power of big business and the power of organized labor. Neither side could defeat the other, nor was it possible—given the nature of class relations and market dynamics—for either side to fully embrace the other. A long-term truce lasted until the 1970s, when the corporations began a process of outflanking their adversary.