chapter 5

The Second American Revolution

By the 1850s, the newly formed Republican Party had emerged as the representative of “free soil, free labor and free men.” The party stood for the hopes of abolitionists who opposed slavery and many Northern farmers, laborers, and industrialists who hoped simply to contain slavery. A key goal was to eliminate the threat of slaveowners’ control over the government which was limiting the growth of the Northern economy (and thus Northerners’ liberty). But the Republicans would eventually be forced to wage total war on slavery.

Antislavery Struggle

While white abolitionists or Abraham Lincoln are often credited with freeing the slaves, many overlook the crucial role played by free black workers and slaves themselves. Southern planters had long boasted that “their” slaves were ignorant “Sambos,” too simpleminded to survive without them. They countered abolitionist tracts by saying that slaves were content, but the planter aristocracy lived in constant fear of slave rebellions. Their fears were well-founded. In 1831, a model slave, Nat Turner, led a rebellion that killed sixty whites. When John Brown and two dozen others raided the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859, their plan was to provide rebel slaves with the weapons to free themselves. Most of Brown’s men were killed by federal troops, and he was hanged after a sensational trial, but his martyrdom inspired many abolitionists.

One of John Brown’s supporters was the African American abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass. Holding back from Brown’s desperate effort because he questioned its practicality, he nonetheless embraced its underlying motivations. In 1857, Douglass had eloquently given voice to essential elements of what would later come to be known as “political science” as well as a fundamental principle of the labor movement:

The whole history of progress of human liberty shows that all concessions made to her august claims have been born of earnest struggle. . . . If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground, they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.

This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress. . . . Men may not get all they pay for, but they must certainly pay for all they get. If we ever get free from the oppressions and wrongs heaped upon us, we must pay for their removal. We must do this by labor, by suffering, by sacrifice, and if needs be, by our lives and the lives of others.

The song “John Brown’s Body” became a favorite of abolitionists and was popular among some Northern troops in the early days of the Civil War. (Significantly, the song was adapted at the beginning of the Civil War to become the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” with words by Julia Ward Howe that essentially repeat the insights expressed by Frederick Douglass. It later was transformed yet again into the labor anthem “Solidarity Forever”—see page 69). An increasing number of Northern working people were rallying to the cause of—as Lincoln later put it—“a nation conceived in liberty” which, “with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it” and should be subject to a government whose policies would be determined by the majority.

War

The threat to the system of slavery posed by the presidential election of Abraham Lincoln caused the majority of Southern states dominated by the slaveowners to break away from the United States. While some poor white farmers and workers in the South were hostile to the new Confederate States of America controlled by the rich plantation owners, many rallied to the defense of their states and local communities, and to a way of life in which—no matter how poor—whites were seen as superior to blacks. This “War for Southern Independence” waged from 1861 to 1865 was the most destructive in U.S. history. The Confederate cause was undermined from the very beginning because the North was able to mobilize a much larger population of working people, and a much more advanced industrial economy. And in the very heart of the Confederacy there was something that doomed its cause from the beginning: millions of African Americans who did not accept the slave-labor system that kept them in bondage.

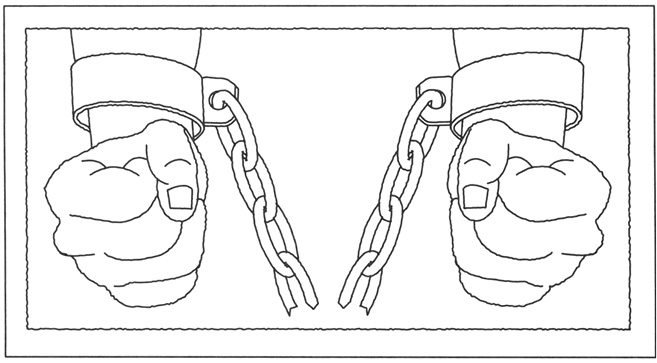

Slaves could be whipped, but planters could not force them to work efficiently (although they were efficient enough when working on their own garden plots). In fact, during the Civil War, slaves’ notorious “inefficiency” mushroomed into what W. E. B. Du Bois termed a general strike that crippled the Southern economy. As soon as the Northern army began to occupy parts of the South, large numbers of slaves began to escape to its lines. Initially, the Northern army returned slaves to their owners and refused to let Northern blacks join the army.

At the early stages of the war, trade unionists and immigrant societies joined the Northern army en masse. But as the massive battles of the war consumed so many lives, the U.S. government was compelled to begin drafting soldiers rather than simply relying on volunteers. The draft proved extremely unpopular, especially as the rich could pay for someone else to serve in their place. By 1863, poor Irish rioted against the war and blacks, leaving dozens of black workers dead. Desperate for troops, Lincoln agreed to let blacks join the army, and black troops often fought with incredible ferocity. The North increasingly fought a war against the Southern economy, finding it necessary to liberate slaves in the process. “The War Between the States” had been turned into a war of liberation. (A sense of the war’s nature is captured in such films as Gettysburg and Glory.)

Some later historians termed it the “Second American Revolution” because it destroyed the institution of slavery and advanced the most radical conceptions of 1776. As Lincoln put it in his 1863 Gettysburg Address, many thousands were giving their lives to preserve a republic “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal” and overtly committed to “government of the people, by the people and for the people.”

Reconstruction

A key to victory was the Emancipation Proclamation, explicitly making the abolition of slavery a centerpiece of the struggle, but when the North finally won the Civil War a question remained: the African American labor force was now free, but free to do what? The Republican Party wanted to stay in power in order to pursue those economic industrialization policies thwarted by the Southern plantation-owners before the Civil War. To achieve this, the Republicans needed a voting base in the South, and they consequently gave black men the right to vote. (Most planters or Confederate politicians—the old Southern ruling elite—were not allowed to vote or serve in government.) Freedmen considered voting desirable, but secondary to desires to reunite families, gain access to the land, and acquire an education. Southern black and white Republicans allocated funds to expand the infrastructure necessary for industry (roads, railroads, harbors). Many humane reforms were adopted that were beneficial to the lower classes. Perhaps most importantly, public schools were built for poor whites and blacks for the first time.

But the most radical of the Republicans insisted that the lower-class majority would not be able to preserve its political power unless it could also secure economic power. They proposed that the big plantations of the old Southern elite be confiscated by the government, and the land be equally divided (“forty acres and a mule,” according to one popular slogan) among ex-slaves and loyal poor whites. This proved to be too radical a demand for most political and economic leaders in the North, who feared that such a violation of rich people’s “property rights” in the South would give working people in the North similar ideas about what should be done with industrial property. The Southern plantation owners got to keep their land, and this concentration of economic power was eventually translated into the reconquest of political power.

The fragile political alliance of poor whites and freedmen collapsed as the federal government allowed the old planter class to launch a wave of terror. Terrorist and paramilitary groups such as the Ku Klux Klan began by killing outspoken blacks, but also white “race traitors,” then increasingly prevented or intimidated most Southern Republicans from voting. By 1877 Northern political and business leaders were prepared to accept the return to power of the old Southern elite, which rallied the bulk of white workers and small farmers in the region under the banner of white supremacy. This acceptance by Northern leaders was based on a gentlemen’s agreement that the Southern leaders would accept national economic policies facilitating the continued development of industrial capitalism. The South’s “new Democrats” went on to pass “Jim Crow” laws that eliminated black political rights and imposed racial segregation. They also limited black rights to change jobs, rolled back publicly financed education, and expanded the use of convict labor. All of these policies kept Southern laborers—white and black—poor, uneducated, and at the mercy of the employing class.

Survival of the Fittest?

The war had transformed the economy of the United States. Sweeping laws were passed that protected industries, created a national network of railroads, and modernized the banking system. Furthermore, industrialists enjoyed lucrative wartime contracts which allowed them to expand their factories and line their pockets. In the face of inflation and corruption, wartime strikes erupted in both North and South, but government still favored owners over workers and most strikes failed. Yet labor’s patience was not unending and major struggles lay ahead.

Many who were inclined to resist labor’s challenge felt compelled to reach for an ideology that shifted away from the simple commitment to government by the people and equal opportunity for all expressed by Lincoln. Drawing on and distorting British naturalist Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, some pro-capitalist intellectuals argued that society involved a struggle for “the survival of the fittest.” The rich had proved to be better than the poor, these Social-Darwinist ideologists argued: an elite had risen to the top, economically and politically, because they proved to be more “fit” than the majority of the people. With the “fittest” in charge of the economy, social progress would be realized. The discontented laborers, small farmers, and others with “envious” or “inferior” minds should not be allowed to penalize their superiors—the big businessmen—by in any way imposing limits on their wealth and power. Those religiously inclined offered a Gospel of Wealth which saw poverty as Divine punishment meted out to the sinful, while wealth was God’s reward to the virtuous.

There were some, however, who saw things differently. By the early 1880s Frederick Douglass—bitterly disappointed over the betrayal of earlier hopes—observed the “sharp contrast of wealth and poverty” resulting from “one side getting more than its proper share and the other side getting less,” commenting that “in some way labor has been defrauded or otherwise denied its due proportion.” Douglass’s conclusion was similar to that of many labor activists: “As the laborer becomes more intelligent he will develop what capital he already possesses—that is the power to combine and organize for its own protection.” A lesson for black and white workers, he felt, should be taken from the earlier antislavery struggle: “Experience demonstrates that there may be a slavery of wages only a little less galling and crushing in its effects than chattel slavery, and that this slavery of wages must go down with the other.”