Chapter 39

General Information

When on your hunting trips do not try to belittle the back woods folk even though you are a college man and your home is in a big city.

While your education and personal appearance may be far superior to theirs, they may be getting just as much pleasure out of life as yourself and when it comes right down to country common sense, they probably have you beaten.

A few years ago a New Jersey nimrod, while fishing in Northern Maine got mixed up in his direction while attempting a shortcut to camp. He finally ran into a barefoot boy and started asking him questions without admitting the fact that he did not know the way home. Unable to get an intelligent reply that would help him out of his predicament he finally said, “I guess you don’t know much anyway, do you?” The boy answered. “No, but I’m not lost.”

Last Fall we received from our good friend, Robert B. Summers, a letter as follows:

“The Summer of 1949 my wife and I were vacationing on a small island off the Maine coast, called Vinalhaven. There was an old man who lived alone on the Northeast tip of this island, sort of isolated from the rest of the natives. We always made it a practice to call on this old man while we were there. He was so pleasant and very highly educated. So one day while we were making a call some young summer people from New York City were out hiking around the island. They had lost their way back and stopped at this old man’s house to inquire their way home. Before they left they said to the old man, ‘Do you know, Mister, there are some queer people on this island.’

“The old man says, ‘Yes, I know there are, young man, but they will all be gone by Labor Day.’”

BILL GORMAN > L.L. was always likeable. I remember being five years old and sitting on L.L.’s lap, stitching a pair of Maine hunting shoes. I’d hate to be the customer that got that pair, but L.L. was always patient and loved to have us take part in the tradition.

Summer Care of Snowshoes

Wipe clean and varnish both the wood and webbing. Any high grade spar-varnish will do. Two coats are better than one, but in any case, they should be thin coats.

Tie the shoes securely together, back to back, and force block of wood into the space between the toes.

Place them out of the sun and hang by the tail. Suspend by wire so that mice or squirrels cannot get at them.

You may be the big toad in the puddle when you are home but don’t try to poke fun at the “Small Town” folk until you are sure you are “out of the woods.”

There are about twenty-three million hunters in the United States. Therefore, when you will go fishing or hunting do not set your expectations too high. You may fish all day and not get a strike. You may hunt all day and not even see a deer. In fact you may go home empty-handed. Therefore, make up your mind to have a good time. Enjoy camp life and exercise in the open air and you will be well repaid for your trip. I have hunted three days without seeing a deer. On the forth day I had my deer hung up and was spotting a trail back to camp before 9 a.m.

To be a successful hunter or fisherman you must have a great deal of patience.

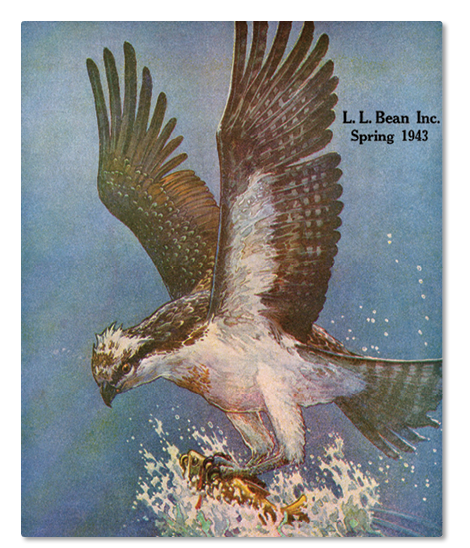

BILL GORMAN > The hunt is just not about the kill. It’s also about enjoying the outdoors. I’ve seen hawks land five feet from me. I’ve had songbirds hop up and down on my arrow. I even had one peck on my hand. Just watching all that activity is satisfying. If you’re successful in the hunt as well, that’s fantastic.

Between its forests, mountains, water bodies, wetlands, coastline, and islands, Maine is blessed with a rich diversity of habitat and wildlife species. Naturally, a priority of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (MDIF&W) is to maintain that diversity and conserve the state’s resources for future generations. It does this through wise use and proper management, and its job of balancing the needs of various parties interested in wildlife is not easy.

Through the years the state has enjoyed a number of conservation success stories worth telling.

Moose

According to early explorers, moose were plentiful in New England in the 1600s. By the early 1900s, however, Maine’s moose population had declined to about two thousand. Excessive hunting was mostly to blame, with additional factors being clearing forestland for farms and increased incidence of fatal brainworm because of increasing numbers of deer (deer are carriers of brainworm, but do not suffer the ill effects).

Moose seasons varied in length and bag limit and were closed periodically. In 1936 the season was closed again, and it remained closed until 1980. That year seven hundred permits were issued to Maine residents for a six-day, September season, and 635 moose were taken. Following that, carefully controlled hunts were held on an annual basis, and moose numbers were monitored closely. In 2010, 3,188 permits were issued for four different seasons, and 2,393 moose were taken. The state’s moose population currently stands above 29,000, which, according to state wildlife managers, is a healthy population for the amount of moose habitat that is available in the state.

Wild Turkeys

Due mostly to extensive land clearing for farming and unrestricted shooting, wild turkeys were virtually eliminated in Maine in the early 1800s. Several attempts to reintroduce turkeys to the state were made in the 1940s and ’60s, but it wasn’t until 1977, when Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife biologists took forty-one turkeys that had been trapped in Vermont and released them in York County, that the birds began to take hold. Since then, thanks to in-state trap-and-transplant efforts and the release of an additional forty turkeys from Connecticut in the late 1980s, the population of Maine’s largest game bird has taken off. Today estimates put the state’s turkey population at between 50,000 and 60,000 birds, and state wildlife managers have achieved about 90 percent of their goal of having viable turkey numbers wherever suitable habitat exists.

Whitetail Deer

Conservation success doesn’t always mean having the largest population of a particular species. Numbers need to be balanced with habitat.

For the past four hundred years, whitetail deer numbers have fluctuated based on land-use practices, predation, climate change, and disturbances like wildfires and floods. The state has been regulating deer hunting since 1830, when it implemented the first season (with no bag limit). Since then the state has been tweaking seasons, limits, and other regulations in order to try to reach management goals. Peak harvests occurred in the 1950s, when the state was wintering about 275,000 whitetails and either-sex hunting regulations were in effect.

More recently, harvests have been lower, but this can be attributed to not only fewer deer, but also fewer hunters. In addition, increasing development in some areas has necessitated switching from firearms hunting to bowhunting only.

In the past couple of years, deer numbers in northern, eastern, and western Maine have been estimated at 200,000 - 255,000, below the goals of the MDIF&W as well as the expectations of hunters. As a result, significant efforts are being made to restore populations in those areas. This is a long-term project, but if the track record of the department is any indication, chances are good that sportsmen and other wildlife enthusiasts will have another conservation success story to tell.

— Bill Gorman