THE ELEMENTS OF dream, ritual, dance, and sexual metaphor abound in the avant-garde films made in America in the late 1940s and early 1950s. For a time the dream generated a form of its own, occurring simultaneously in the films of several independent artists. I have called this the trance film. Its history is an extension of the initial discussions of the American avant-garde film in Parker Tyler’s book The Three Faces of the Film.

In his captions to the illustrations for that volume, Tyler offers a brilliant and succinct analysis of the form and history of the genre. Under a still from Brakhage’s Reflections on Black he writes:

The chief imaginative trend among Experimental or avant-garde filmmakers is action as a dream and the actor as a somnambulist. This film shot employs actual scratching on the reel to convey the magic of seeing while “dreaming awake”; the world in view becomes that of poetic action pure and simple: action without the restraints of single level consciousness, everyday reason, and socalled realism.1

Then, between stills from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Meshes of the Afternoon, he writes:

Cesare, the Somnambulist of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, has been an arch symbol for subsequent avant-garde film-making, one of whose heroines is seen below. Art is the action which knits the passive dreamer, as it knits the passive spectator, to realms of experience beyond his conscious and unconscious control. In such realms, wild excitement is often found by way of the movies. But rarely, except in avant-garde films, does the strict pulse of beauty govern the engines of “wild excitement.”2

If Cesare is the archetypal protagonist of the trance film, then the form of Jean Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un Poète is the model for its development. The trance film as it emerged in America has fairly strict boundaries. It deals with visionary experience. Its protagonists are somnambulists, priests, initiates of rituals, and the possessed, whose stylized movements the camera, with its slow and fast motions, can re-create so aptly. The protagonist wanders through a potent environment toward a climactic scene of self-realization. The stages of his progress are often marked by what he sees along his path rather than what he does. The landscapes, both natural and architectural, through which he passes are usually chosen with naive aesthetic considerations, and they often intensify the texture of the film to the point of emphasizing a specific line of symbolism. It is part of the nature of the trance that the protagonist remains isolated from what he confronts; no interaction of characters is possible in these films. This extremely linear form has several pure examples: Curtis Harrington’s Fragment of Seeking (1946) and Picnic (1948), Gregory Markopoulos’s Swain (1950), Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks (1947), Stan Brakhage’s The Way to Shadow Garden (1955), and Maya Deren’s At Land (1944), her first film after Meshes of the Afternoon. The genre naturally has had many variations, transformations, and mixed uses. These I will discuss later.

At Land is the earliest of the pure American trance films. In it, the heroine, again played by Maya Deren, is washed out of the backward-rolling waves of the sea; she rises, crawls over logs and rocks until she finds herself in the middle of a banquet table, crawls down it without being noticed by the banqueters, and steals a chess figure from a board at the end of the table on which the pieces seem to move by themselves. The middle of the film records her pursuit of the chess man through other similar landscapes: beach, tree, rocks, and interiors. No one seems to notice her. At one point, she loses the chase and finds herself talking with a man who is constantly being replaced by other men. Then, finding another chess game in progress, she steals again. This time, as she flees with the chess man, she is watched by images of herself from the rocks, the beach, the banquet, and the tree. In a series of dramatic temporal ellipses, she disappears among sand dunes.

Here is the classic trance film: the protagonist who passes invisibly among people; the dramatic landscapes; the climactic confrontation with one’s self and one’s past. Meshes of the Afternoon had some of these elements, but its intricate, coiled form gave a more personal, less archetypal tone to its narrative. The form of At Land is completely open. The camera is generally static. This time Hella Heyman photographed and Maya Deren set up the compositions. The principle of the editing, whereby every scene seems magically continuous with the previous, must have been planned in advance. For instance, as the protagonist crawls from the dead tree to the banquet table, we see her head disappear beyond the top of the frame in one scene, and in the next, now in the banquet hall, it rises from the bottom of the frame. As she pulls herself up into the hall, we see a final shot of the tree as her dangling leg passes through the top of the frame. This kind of montage must be provided for in advance, and, in fact, is the basis of the structure of this film.

In Meshes, Hammid and Deren had employed a number of montage illusions which created spatial elisions or temporal ellipses for the sake of the psychological reality which informed their vision. In At Land, Deren, now on her own, conceives from the beginning that the film should continually use these figures of cinematography as formal or stylistic devices. Indeed, they are essential principles of her film. She says as much in a letter to James Card:

Anyway, Meshes was the point of departure. There is a very, very short sequence in that film—right after the three images of the girl sit around the table and draw the key until it comes up knife—when the girl with the knife rises from the table to go towards the self which is sleeping in the chair. As the girl with the knife rises, there is a close-up of her foot as she begins striding. The first step is in sand (with suggestion of sea behind), the second stride (cut in) is in grass, third is on pavement, and the fourth is on the rug, and then the camera cuts up to her head with the hand with the knife descending towards the sleeping girl. What I meant when I planned that four stride sequence was that you have to come a long way—from the very beginning of time—to kill yourself, like the first life emerging from the primeval waters. Those four strides, in my intention, span all time. Now, I don’t think it gets all that across—it’s a real big idea if you start thinking about it, and it happens so quickly that all you get is a suggestion of a strange kind of distance traversed … which is all right, and as much as the film required there. But the important thing for me is that, as I used to sit there and watch the film when it was projected for friends in those early days, that one short sequence always rang a bell or buzzed a buzzer in my head. It was like a crack letting the light of another world gleam through. I kept saying to myself, “The walls of this room are solid except right there. That leads to something. There’s a door there leading to something. I’ve got to get it open because through there I can go through to someplace instead of leaving here by the same way that I came in.”3

Hammid remembers that the original conception of that scene in Meshes was specifically Maya Deren’s.

Nevertheless, in her first solo film she is still very much under the influence of her collaborator. The denouement, in which the protagonist is seen by images of herself, comes right out of the center of the earlier film, which may derive from Hammid’s own first film. The fluid, rounded space of Meshes is echoed in the linear style of At Land, with its soft cutting on motion and illusory elisions. But the rich texture of interlocking alternations of subjective camera and synedochic framing of elaborate and dramatic pans, which Meshes owed to the creative involvement of Hammid, disappears here, as the photographer worked under the direction of the author-actress.

Trance films in general, and At Land in particular, tend to resist specific interpretation. In the case of At Land, one could point out the allusions to sexual encounter—the moustached man in bed, and the caressing of the girl’s hair by the beach—or interpret the banquet scene in terms of the individual’s resistance to the social organism, but it would be difficult to extend such an interpretation to all the actions of the film.

Deren is a good critic of her own work when she writes in her notes for this film:

The universe was once conceived almost as a vast preserve, landscaped for heroes, plotted to provide them the appropriate adventures. The rules were known and respected, the adversaries honorable, the oracles as articulate and as precise as the directives of a six-lane parkway. Errors of weakness or vanity led, with measured momentum, to the tragedy which resolved everything. Today the rules are ambiguous, the adversary is concealed in aliases, the oracles broadcast a babble of contradictions.

Adventure is no longer reserved for heroes and challengers. The universe itself imposes its challenges upon the meek and the brave indiscriminately. One does not so much act upon such a universe as re-act to its volatile variety. Struggling to preserve, in the midst of such relentless metamorphosis, a constancy of personal identity.4

As Maya Deren began to move more confidently from writing to film, her interest in form became clearer. She has left us six films. In each one of them she explored a new formal option. I have already suggested that her interest in the overlapping of space and time arose as a result of the editing of Meshes of the Afternoon. That interest never flagged during her film career. In At Land she pursued an open-ended narrative form based on her initial discoveries. In her next film, A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945), she returned to her old interest in dance to make a completely new kind of film.

It is clear that even in the first two films her concern with dance was not suppressed. The plastic space of both films, which cutting on motion makes possible, is closely akin to the dancer’s art of connecting motions.

Even before her collaboration with Hammid on Meshes of the Afternoon, she had spoken casually with dancers about recording ethnic dances on film. After the making of Meshes and her revelation that the space and time of film was a made space and time, a creative function and not a universal given, she was no longer interested in the camera as a simple recording device for the preservation of dances. A Study in Choreography for Camera was a dance film with equal participation by both arts. She subtitled it “Pas de Deux,” referring to the one dancer and the one camera.

She did not herself appear in this film. Since she had no formal training, she enlisted the help of a dancer, Talley Beatty, as her one performer. The film they made is extraordinarily simple—a single gesture combining a run, a pirouette, and a leap. It lasts no more than three minutes.

The opening shots recall the climax of At Land; in both instances she used one pan movement of the camera to encompass several temporal ellipses. It is as if she were panning through time as well as over space. At Land climaxes with one sweeping shot, actually made up of a series of carefully joined shots, of herself walking away over sand dunes. As the camera in its leftward motion sees each successive dune, she crosses over the top and disappears on the other side. Thus in the evocation of a very short time (the time of moving the camera on its tripod) we see the illusions of long periods of time, the walking between dunes having been eliminated.

Choreography begins with a circular pan in a clearing in the woods. In making the one circle the camera periodically passes the dancer; at each encounter he is further along in his slow, up-stretching movement. At the end of this camera movement, he extends his foot out of the frame and brings it down in a different place; this time, inside a room. The dance continues through rooms, woods, and the courtyard of a museum until he begins a pirouette, which changes, without a stopping of the camera, from very slow motion to very fast. Then he leaps, slowly, very slowly, floating through the air, in several rising, then several descending shots, to land in a speculative pose back in the wood clearing.

The dance movement provides a continuity through a space that is severely telescoped and a time that is elongated. The film has a perfection which none of Maya Deren’s other films ever achieved.

There are two aspects of this film that deserve consideration. One is formal, concerning the emergence of a new way of composing films; the other is synthetic, concerning the possible use of dance in film, and more broadly the problem of prestylization, which Erwin Panofsky, in his essay “Style and Medium in the Motion Pictures” (1934), identified as the failure of all films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (his example) which use aesthetic objects such as expressionistically painted sets or ballet movement instead of natural gestures and real scenes as raw material.

Choreography for Camera forecasts the shift from narrative to imagistic structures within the avant-garde film movement. Before it, there had been several ways of putting together such films. Narrative had been the most common. By this I do not mean simple story-telling, but abstracted narrative forms such as Un Chien Andalou, Meshes of the Afternoon, and the trance films. Thematic composition was another possibility: the city symphonies, usually describing a day in the life of a city; or tone poems about a season, a place, or a form of matter, such as Steiner’s H2O about water patterns. The sophisticated thematic structures were extended metaphors—one thinks primarily of Léger’s Le Ballet Mécanique, in which graphic abstraction, repetitive human actions, and machines in operation are synthesized into an image of a gigantic social supermachine.

Maya Deren introduced the possibility of isolating a single gesture as a complete film form. In its concentrated distillation of both the narrative and the thematic principles, this form comes to resemble the movement in poetry called Imagism, and for this reason I have elsewhere called a film using this device an imagist film.5 There I concentrated on pure examples and described the inevitable inflation of the simple gesture to contain more and more aesthetic matter. Kenneth Anger’s Eaux d’Artifice, Charles Boultenhouse’s Handwritten, and Stan Brakhage’s Dog Star Man: Part One provided the examples.

In brief, all of these films describe a simple action like the leap of Choreography. In Anger’s film it is the walk of a heroine through a baroque maze of fountains in pursuit of a flickering moth. Boultenhouse’s film revolves around the slamming of a fist on a glass tabletop, and Brakhage’s describes a man climbing a mountain. Each example represents a progressive stage of inflation, whereby lateral or foreign material is introduced around the essential action without completely disrupting its unity or continuity.

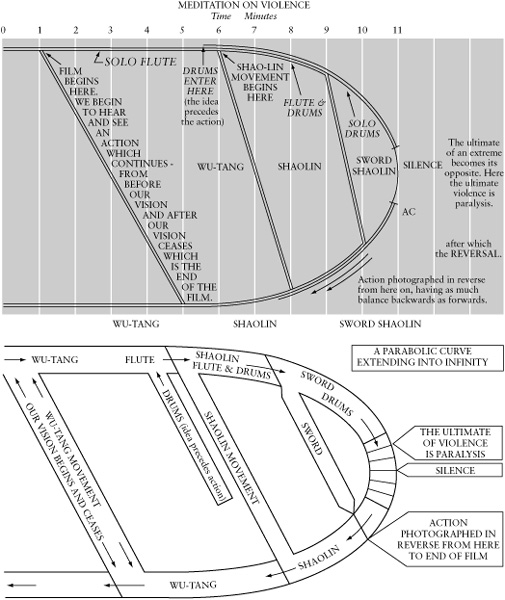

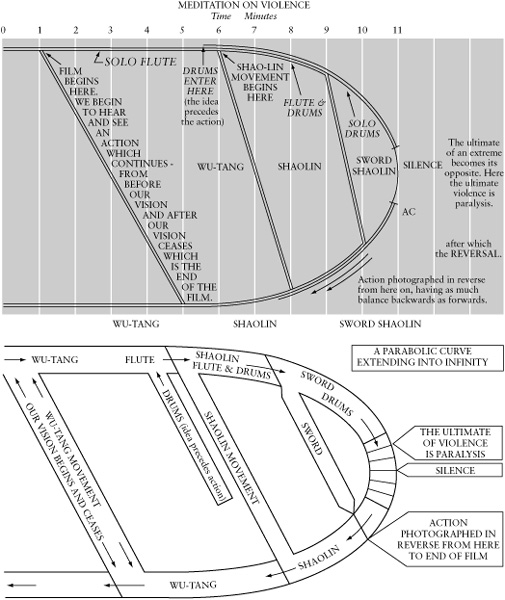

Maya Deren herself returned to the imagist film to make Meditation on Violence in 1948, and again just before she died when she conceived the idea of the haiku film. The structure of Meditation on Violence almost duplicates that of Choreography for Camera on a larger scale, with a proportionate loss of tension. Deren’s own notes for the shooting of the film employ two parabolic arcs. Theoretically, the film describes in a single continuous movement three degrees of traditional Chinese boxing—Wutang, Shao-lin, and Shao-lin with a sword. A long sequence of the balletlike, sinuous Wu-tang becomes the more erratic Shao-lin; then for two or three minutes in the middle of the film there is an abrupt change to leaping sword movements, in the center of which, at the apogee of the leap, there is a long-held freeze-frame; finally we see the boxer move back through Shao-lin to the original Wu-tang. For each transition there is a change of background and filmic style. We see the Wu-tang against a curved, unbroken black wall; the Shao-lin takes place in a room with alternate black and white walls to emphasize its angularity. The montage, which had been very fluid with elided joining, becomes appropriately pronounced and angular. The sword play occurs outside, with jump cuts, slow motion, and the freeze-frame. The last portion of the film is printed in reverse motion, but the continuity of the movement disguises this from the spectator.

So much for its abstract plan. In the notes for this film, Maya Deren makes some extravagant intellectual claims for it, which are interesting because the film fails to live up to them:

The film consists not only of photographing these movements, but attempts an equivalent conversion, into filmic terms, of these metaphysical principles. The film begins in the middle of a movement and ends in the middle of a movement, so that the film is a period of vision upon life, with the life continuing before and after, into infinity. The rhythm of the negativepositive breathing is preserved in the rhythm at which the boxer approaches and recedes from the camera. Both the photography and the cutting of the Wu-Tang sections are deliberately smooth and flowing, so that no “striking” shots or abrupt cuts occur in these sections. This whole approach is further amplified in the diagram and notes. Moreover, it seemed significant that not only were these movements related to metaphysical principles (an inner concept) but that they were training movements—the self-contained idea of violence, not the actual act. Training is a physical meditation on violence. So, too, the film is a meditation. Its location is an inner space, not an outer place. And just as a meditation turns around an idea, goes forward, returns to examine it from another angle, so here the camera, in the WUTANG section, revolves around the movements of the figure, returns to some previous movement to examine it from another angle altogether, to achieve a “cubism in time.”

However, meditations investigate extremes, and life, while ongoing and non-climactic in the infinite sense, contains within it varieties and waves of intensity. So this film, as a meditation, proceeded beyond the WU-TANG School, to examine where the -LIN concepts of aggression would lead. This school, called “exterior,” is based on exterior conditions of opportunity. Its emphasis is upon strength, impact, sudden rhythms, and the body is not treated as a whole. Rather, the sharp strength of the arms and legs is emphasized for independent action. The logical conclusion is to even implement this sharpness with a sword. And so, in the film, the increasing violence bursts into an extension: the arm sprouts a sword.

Even this is carried forward. The climax of this meditation on violence is a paralysis. From which point the return is a reversal. The movements are actually photographed in reverse from this point on.6

Meditation on Violence, from a theoretical point of view, is a film overloaded by its philosophical burden.

Maya Deren’s initial creative period extended from the completion of Meshes of the Afternoon in 1943 through the making of At Land, Choreography for Camera, and Ritual in Transfigured Time, the discussion of which I have postponed for a few pages—three years of almost uninterrupted film production. At the end of that period she published a book of theory, An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form, and Film, and left for Haiti, initially to make a film, but eventually to write her study of Haitian mythology, Divine Horsemen. Meditation on Violence was the first film she completed after this period. It bears the full burden of her theoretical and philosophical thought in the intervening years. It suffers, as does her subsequent film, The Very Eye of Night, released after a silence of ten years, from excessive stylization, both intellectual and graphical. Yet her aspiration to use film to imitate the process of the mind was exalted and certainly has been felt by other film-makers within the American can avant-garde sphere.

In her program notes she clarifies her attempt to represent mental processes cinematically:

The camera can create dance, movement and action which transcend geography and take place anywhere and everywhere; it can also, as in this film, be the meditating mind turned inwards upon the idea of movement, and this idea, being an abstraction, takes place nowhere or, as it were, in the very center of space.

There the inner eye meditates upon it at leisure, investigates its possibilities, considers first this aspect and angle, and that one, and once more reconsiders, as one might plumb and examine an image or an idea, turning it over and over in one’s mind.7

The spectator is confronted with something more restricted than this. There is the boxer, moving before a painfully artificial black wall; then comes a change of boxing style before an equally contrived, angular set of walls, and ultimately, in open space, the boxer is costumed and leaping with a sword. In Choreography for Camera, speed was the key to the unity and tension of the image. By elongating the action in Meditation on Violence, the fusion of spaces, costumes, boxing modes, and cinematic styles dissolved; it fragmented into vague sections. In principle, such an elongation is not impossible. We shall see later how Stan Brakhage successfully elongated the imagist film in Dog Star Man: Part One without losing its essential tension.

In Ritual in Transfigured Time, the film which immediately followed Choreography, Deren openly grappled with the problem of using dancers in a film. The result is her most complex film, and the one that most fully contains her achievements, her theories, and her failures.

Formally, Ritual in Transfigured Time is a radical extension of the trance film in the direction of a more complex form. That form, the architectonic film, which was to emerge in the early 1960s after other ambitious efforts, aspired toward myth and ritual.

The pure trance film has a single protagonist—all other human figures being distinctly background elements—and a linear development. Ritual has two principal figures (although ultimately the film reduces itself to the initiation of a single persona, the female) and utilizes several others more dynamically than does the trance film. Despite the attempt at a continual and gradual movement from trance into dance, Ritual in Transfigured Time has three parts: an opening, a party, and a dance in the open air.

The images of this film, unlike any of her others, evoke traditional interpretations. They are not so much symbolic as archetypal, drawn primarily from the visual vocabulary of ancient mythology. The images of Norns, of Fates, and of Graces adorn a film which, in its center, describes a sexual rite of passage. In her notes Maya Deren called this rite the passage of the “widow into bride.”

Beyond the classic images, we see the same enigmatic, obsessive totems of her other films. The confrontation of the self takes a new form here. In Meshes of the Afternoon we saw, through a camera trick, three simultaneous, juxtaposed images of the heroine in a single shot; in At Land, the editing of shots of her looking offscreen, followed by a shot of her in a different location as if filmed from the angle of vision of the previous glance, created the illusion of meeting with the self. Now, here, the self is composed of different bodies; their metamorphosis occurs through cutting on motion. The gesture begun by one is continued by the other. The result is an evocative ambivalence of identity and a sense of mysterious, perpetual metamorphosis.

The form of Ritual in Transfigured Time anticipates the even more complex architectonic films of Gregory Markopoulos and Stan Brakhage, in the early sixties, though it lacks their precision of proportions, and their overall evenness of execution. Because of her dedicated interest in form and her reluctance to repeat her previous achievements in that dimension, Deren tended to overextend her formal ambitions at times; as a result she came to cinematic forms earlier than she could handle them well.

Thus her first four films (including Meshes of the Afternoon) rehearse in general outline the subsequent evolution of forms within the American avant-garde cinema over the following two decades. Her summary of her achievements in the letter to James Card, previously excerpted, takes on a prophetic tone:

Meshes is, one might say, almost expressionist; it externalizes an inner world to the point where it is confounded with the external one. At Land has little to do with the inner world of the protagonist, it externalizes the hidden dynamics of the external world, and here the drama results from the activity of the external world. It is as if I had moved from a concern with the life of a fish, to a concern with the sea which accounts for the character of the fish and its life. And Ritual pulls back even further, to a point of view from which the external world itself is but an element in the entire structure and scheme of metamorphosis: the sea itself changes because of the larger changes of the earth. Ritual is about the nature and process of change. And just as Choreography was an effort to isolate and celebrate the principle of the power of movement, which was contained in At Land, so I made, after Ritual, the film, Meditation on Violence, which tried to abstract the principle of ongoing metamorphosis and change which was in Ritual.8

I will show in this book how the trance film gradually developed into the architectonic, mythopoeic film, with a corresponding shift from Freudian preoccupations to those of Jung; and then how the decline of the mythological film was attended by the simultaneous rise of both the diary and the structural film. The latter are extensions of the imagist form in the direction of visual haiku, epiphanies, and diaries. They are static, epistemologically oriented films in which duration and structure determine, rather than follow, content.

In the opening scene of Ritual in Transfigured Time, a woman, played by Maya Deren, stands in a double doorway. She passes from one of the two visible rooms into the other to get a scarf, then returns to the first room with a swatch of yarn. With her head she signals another woman, “the widow,” in from the darkness. Like the first woman, the widow is dressed in black, but she is more mournful and she walks with her hand out before her like a somnambulist. She comes in and sits before her, making a ball from her yarn. The first woman, “the invoker,” sings, laughs, and chants while she juggles the wool between her hands in gradually slower and slower motion. The widow, hypnotized and enchanted, continues to wind the wool in a ball.

With another turn of her head the invoker indicates that a third woman has entered the room by yet another door. We can call her “the initiator” or “the guide.” She beckons the widow while at the same time the invoker hieratically raises her arms, dropping the yarn and thus releasing her from the spell. When the widow looks back, the invoker’s chair is empty.

This opening episode is distinguished by compositions-in-depth of more sophistication than anywhere else in Maya Deren’s films. A geometrical sense of the relative placement of the three women determines the editing sequence, which is accented by rapid alterations in the speed of recording, causing sudden shifts from slow to normal motion. The composition-in-depth and the handling of a large group of actors in the subsequent scene indicate an advance in Maya Deren’s conception of cinematic form and in her powers as a director.

The form of the opening passage is that of the trance film; slow motion was one of its chief cinematic means of expression. In the party scene, the trance is replaced by a collective choreomania, as the entire crowd moves again and again in a half-dozen repetitive patterns; they stop short, suspended in a frozen frame. The means of achieving this effect were simple. Maya Deren printed several copies of a few complex movements, showing the wanderings of the guide, the hesitant movements of the widow, and the pursuit of her by a young man, who presumably seeks to meet her. Then she simply repeated the very same shots at fixed intervals and punctuated them with the freezes. The result was the highly successful rendering of dance movement from elements outside the dance. It is this middle passage that makes one think that Maya Deren was openly trying to deal with the problem of the prestylization of dance in film, although she never acknowledged the problem as such in her writings.

When the young man meets the widow—they literally “bump into one another”—the scene cuts away to an open field in which the performers are posed, faces just about touching, exactly as they were at the party. They occupy the same portion of the film frame. Thus the transition is sudden and clean, even though the young man is no longer fully dressed but bare-chested, and the widow now has bare legs and feet.

Then they dance. Behind them three female figures from the party, resembling the Graces, dance before neo-classic columns. The guide is one of the Graces. The dance of the couple becomes one of flight and pursuit. As she runs, the widow turns into the invoker, then back again. In the transition there is a change of scarfs, from mourning black to bridal white.

It is the widow again who enters a gate to find her pursuer transformed into a statue on a pedestal. In slow motion with several freeze frames he gradually comes to life, and after some instantaneous petrifications in midair, he leaps to the ground. As the pursuit continues, the heroine runs full speed, while the young man follows in graceful ballet leaps in slow motion. Physically, the situation of Meshes of the Afternoon is here reversed, as the fleeing runner cannot make gains on the slow-motion pursuer.

They pass by the guide in their chase. Just as he reaches for her, there is a metamorphosis from widow to invoker, and she runs into the sea. As she sinks we see her in negative, her black gown now white while she changes again from invoker to widow, now prepared as a bride for the young man who has not followed her into the water.

Ritual in Transfigured Time is Maya Deren’s great effort at synthesis. There is, on the one hand, the transformation of somnambulistic movement to repetitive, cyclic movement; that is, to dance. There is also the fusion of traditional mythological elements—the Graces, Pygmalion, the Fates—with private psycho-drama (the film-maker herself plays the invoker); and an attempt to present a complete ritual in terms of the camera techniques she had utilized in her earlier films—slow motion, freeze-frame, repetition of shots, and variations on continuity of identity and movement.

Its precursor, Jean Cocteau’s first film Le Sang d’un Poète (1930), bridged a transition from an avant-garde cinema centered in Paris to one dominated by Americans. Of all the independent films from Europe this one had the most influence on those who would revive the avant-garde cinema toward the end of the Second World War. Two aspects of Cocteau’s film give it this privileged position: its manifestly reflexive theme, and its ritual. The film opens with an allegory of the relationship of the authorial persona to the temporality of cinematic representation. We see Cocteau, surrounded by the klieg lights of a movie studio, blocking his face from the camera with a classical dramatic mask, which foreshadows the moment in the film when the film-maker will declare in a handwritten title that he is trapped in his own film; yet what we see of him then is still another mask, this time fashioned after his own profile. The declaration of the enigmatical distance between the authorial self and his mediating persona is coordinated with a bracketing device that affirms that the film transpires in no time, or in the instant between two photograms. We see a towering smokestack begin to crumble, an image reminiscent of many of the Lumières’ one-shot films. At the end of the film the smokestack completes its fall. By bracketing his film this way, Cocteau wants the viewer to understand that his mythic ritual occurs in “transfigured time.”

The events of Le Sang d’un Poète bear a general resemblance to the trance film: a single hero, the poet, finds that the painted mouth he wiped from a canvas continues to live in his hand. It talks to him; it stimulates him sexually as he runs his hand along his body. Finally, with great effort, he transfers the mouth to a statue, which comes alive. The metamorphosis of statue into muse is attended by an alteration of the space in which it occurs; for in this process the door and window of the poet’s chamber disappear. His sole exit is through the mirror. So he plunges into a realm of fantastic tableaux which seem to exist solely for his inner education.

The Hôtel des Folies Dramatiques, which the poet explores after crossing the threshold of the mirror, is a series of rooms, accessible only to sight through the keyhole. In each, a principle of cinematic illusionism is illustrated with the naive exuberance of Méliès’ films, which Cocteau must have first encountered in his childhood. The assassinated Mexican is revived in reverse motion; camera placement allows us to see a girl clinging to walls and ceiling; finally, a hermaphrodite is constructed of flesh, drawn lines, and a roto-relief in Duchamp’s style so that it is not only an illusionary blending of male and female characteristics but a figure synthesized from the very arts which feed into cinematic representation. The myth of the poet that Cocteau elaborates moves freely among centuries and between childhood and maturity.

Back in the chamber, the poet destroys the statue and in so doing is changed into one himself. In the subsequent episode, a group of young students break up the statue to use as fatal ammunition in a snowball fight. Over the bleeding body of a slain student, the muse and the poet, both in the flesh, play a game of cards which culminates, again, in his suicide.

Parker Tyler has pointed out, again in the captions to the illustrations of The Three Faces of the Film, the persistence of the motif of the statue within the avant-garde film tradition. Willard Maas, a contemporary of Maya Deren who began making films in 1943 with his wife Marie Menken and the poet George Barker (Geography of the Body), invoked this motif on a grand scale in his most ambitious project, Narcissus (1956). The hero, played by his collaborator Ben Moore, wanders in desolation through an outdoor corridor formed by two rows of busts of the Roman emperors. Unlike Cocteau’s or Maya Deren’s statues, these do not come alive, yet in Maas’s film their animation is potential, and the pathos of that fragment of the trance derives from the refusal of the statues to live and advise.

(a) The cinematic Pygmalion: The poet of Jean Cocteau’s Le Sang d’un Poète leaves the statue-muse. (b) He peeps through a keyhole in the Hôtel des folies dramatiques.

Behind all the employments of the statue in the trance film, however obliquely, is the myth of Pygmalion. In his revival of that myth in the terms of a “magical” illusionism of cinema, Cocteau initiated a cinematic ritual that a whole generation of American film-makers felt sufficiently vital to restate in their own terms.

The temporal ambiguity that Cocteau postulated between any two consecutive frames of a continuous shot operated independent of the camera which photographed that shot. In Maya Deren’s reworking of that suspended temporality, account would be taken of the status of the camera in cinematic metaphors of reflection. She did not do this as Vertov had done and as many would begin to do in the 1960s by introducing the filmmaking apparatus into the imagery of the film. Her early, and best, films dwell instead upon the temporal and spatial complexities of representing the self in cinema. In Meshes of the Afternoon, the window, as a metaphor for cinematic representation, has neither the amorphous presence of Man Ray’s distorting lens or the barrier quality of the window in Un Chien Andalou; it is, rather, a mirror. For Deren, and subsequently for most of the American independent film-makers who followed her, film-making was essentially a reflexive activity.

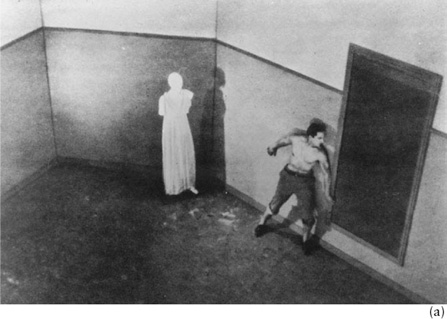

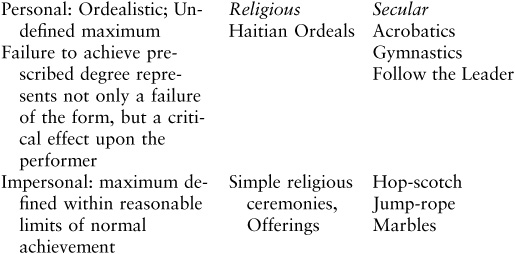

Ritual in Transfigured Time was meant to be first of several cinematic investigations of ritual. In a request for a Guggenheim foundation grant, Maya Deren proposed a complex film correlating the ritual aspect of children’s games with traditional rites as they survive in Bali and Haiti. She had enlisted the aid of Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, whose exhibition and catalogue of South Seas ritual objects at the Museum of Modern Art at that time influenced the conception of the film. In her request for the grant she appended the following chart of ritual parallels and wrote as an example for the project:

The widow of Maya Deren’s Ritual in Transfigured Time flees the living statue and “marries” the sea, drowning in negative.

When a child hopes to be given a bicycle for Christmas, it may resolve to walk all the way home from school without stepping on a crack in the sidewalk. Not only is the form of this little ritual completely unrelated to its objective, but that separateness may be frequently reinforced by secrecy: one of the conditions being that no one, and especially the parents, be aware of the performance.9

Under the title “Cinematics,” she outlined some of the means of achieving her aim, which she had previously stated as “stating the almost fixed constancy of the idea of ritual action”:10

RITUALS INVOLVING MINIMIZATION OF PERSONAL IDENTITY

RITUALS INVOLVING COMPACTS OF BEHAVIOR

(Since the degree of skill is here often critical, the identity of the performer is either retained, or at most on an anonymous or collective level. Where it is greatly minimized, it overlaps with category three of the Identity Rituals.) (The specific work on Bali and Haiti in this connection still remains to be done.)

In 1946 the Guggenheim Foundation granted her their first fellowship for work in creative motion pictures and she went to Haiti to film rituals and dances. That film was never finished. As late as 1954 she had written that she did not have sufficient footage for a documentary film about Haitian ritual. Presumably, the plan for the cross-sectional ritual film was quickly abandoned. While in Haiti, her career as a film-maker was radically deflected. The film she planned to make became a book about Haitian cults, published as Divine Horsemen.

In the preface to her book, she speaks of being “defeated” in her attempt to make the cross-sectional ritual film by the revelation of the mythic integrity of the Haitian cults:

This disposition of the objects related to my original Haitian project—evidence that this book was written not because I had so intended but inspite of my intentions—is, to me, the most eloquent tribute to the irrefutable reality and impact of Voudoun mythology. I had begun as an artist, as one who would manipulate the elements of a reality into a work of art in the image of my creative integrity; I end by recording, as humbly and accurately as I can, the logics of a reality which had forced me to recognize its integrity, and to abandon my manipulations.11

At this time her initial productive spurt had exhausted itself. After returning from Haiti she considered still another ritual film, this time based upon athletic contests. In her search for the appropriate sport, she discovered Chinese boxing, and that inspiration was transformed into Meditation on Violence. Apparently she was not content with the film. By the middle of the 1950s she was “getting a real strong itch to re-edit it, shortening it, and this will improve it, I think.” She never did.

The film involving children’s games and the initial conception of a ritualistic sports film give evidence of the success with which she regarded the central party episode of Ritual in Transfigured Time, in which she had raised familiar gestures to the level of ceremony. Throughout the fifties she continued to conceive of films which would choreograph skilled but familiar maneuvers. Each new subject entailed formal evolution. If the film of children’s games combined with Balinese and Haitian rituals, even in its speculative form, represented another stage in the evolution of architectonic form, then a film that she was planning to make in 1954 marks an advance over that. In a letter, she describes her idea of a film involving various circus acts:

Each of the circus acts which occurred to me—the trapeze, the jugglers, the tumblers, the bare-back acts—is composed of sort of suspended TIME phrases. And the form as a whole of the film, which is beginning to emerge, is a kind of series of interlocking time spans—a kind of necklace chain of time-phrases. For example, the tumblers begin their time phrase; about halfway through we are led to the juggler as he begins his time phrase; as the tumblers complete their time phrase we are already in the middle of the juggler’s phrase and, before he is finished, we have been started on the aerialists’ phrase, which is already carrying us by the time the juggler finishes. Actually it would be constructed somewhat like a singing round, so that once the song is started, it never ends, being always carried forward by successive voices. The idea fascinated me as a concept of structure, and as being able somehow to convey the whole sense of timing which, as I had always felt, and as you reaffirmed it, is absolutely basic to all of these activities. Filmically speaking, it means building the whole film in terms of staggered simultaneities.12

Here is the first clear hint of the form by which the architectonic or mythopoeic film would emerge—through “staggered simultaneities”—for in the epic films of Markopoulous, Brakhage, and Harry Smith, the narrative pulse, which normally accents temporal development with climaxes and modulates its rhythm by creating scenic components, gives way to a sense of simultaneity, over which a broad narrative development may, or may not, occur.

The ironies of Maya Deren’s later career are almost tragic. Before her death in 1961, she completed only one more film, The Very Eye of Night. It does not aspire to the same formal innovations as the projected outlines from which I have quoted; her concern was with plastic development, conflict of scale, and dimensional illusion rather than with total structure.

The most pointed irony concerns the circumstances of her death. At the turn of the decade she was living on a pittance from the Creative Film Foundation in return for her energetic work as its secretary (it was a oneperson operation, with nominal officers) and on her husband Teiji Ito’s income as an enlisted private in the army. Just before his discharge, the death of a relative raised hopes of an inheritance for Ito. After a disappointing meeting concerning this inheritance, Maya Deren came down with a terrific headache which led to a paralyzing seizure the next day. Within a week she had suffered her third cerebral hemorrhage and died after three days in a coma. Not long after that the elusive inheritance came through.

She died before she could see the fruit of her work as an apologist and propagandist for the avant-garde film. Yet friends who remember her rages qualify this last irony; she might have found more to oppose than to acclaim in the explosion of film-making and theorizing of the 1960s.

Nevertheless, despite some grievances and voodoo curses against her fellow avant-garde film-makers, Maya Deren worked hard to better the position of the independent film artist and to further the cause of what she called the “creative film” in general. That effort is an important aspect of the visionary tradition within the American avant-garde film. Not only have there been artists making films in the spiritual wake of Poe, Melville, Emerson, Whitman, and Dickinson; there has been a movement among these artists to advance the cause of cinema in general. Such unions have been part of all the arts in this century. This is true, especially in the United States, where a literary tradition grew out of next to nothing in the last century and where a new tradition in the plastic arts was forged. Yet one would be at a loss to discover among painters or writers, dramatists or dancers, an effort as intense or as sustained as that made by independent film-makers for the security of their art. There are obvious reasons for this: the medium is very expensive; its aspirants were relatively few in number until the 1960s; and success in independent film-making is considerably less rewarded than in painting, writing, or drama.

Maya Deren’s vision of a better situation for the film-maker developed out of her experiences as a lecturer and theorist of the medium. In the latter capacity, she has left, in addition to the illuminating notes and articles on her completed films, a coherent body of theoretical writings. They include relatively technical essays for amateur trade publications—“Efficient or Effective,” “Creating Movies with a New Dimension,” “Creative Cutting,” “Adventures in Creative Film Making,” two widely circulated essays on the possibilities of the cinema, “Cinema as an Art Form” and “Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality,” and a pamphlet, written as early as 1946 and published privately by the Alicat Book Shop in Yonkers, New York, An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form, and Film. Just before her death, she did a number of guest columns for Jonas Mekas in the Village Voice which assume a more critical than theoretical stance. The technical articles are essentially autobiographical and offer encouragement to amateurs without money or expensive equipment. They reaffirm the principles of the more general essays without amplifying them.

The basic tenets of her theories can be simply stated. She takes for granted the indexical relationship between reality and the photographic image. In each of her three major articles she insists upon grounding the cinema in photographic realism. Perhaps her experience as a still photographer (she did portraits for Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, and several art magazines) prejudiced her against photographic distortions.

She analyzed the two functions of the film camera as “discovery” and “invention,” the former referring to visions of space and time beyond the capabilities of the human eye, including telescopic or microscopic cinematography on the one hand and slow motion, freeze-frame, or time lapse photography on the other. Among these methods she would continually admit her predilection for slow motion. As an instrument of “invention,” the camera records imaginative constructs in reality and reconstructs them through the illusions of editing. She insists on the principle of recognition rather than graphic composition within the photographic image:

In a photograph, then, we begin by recognizing a reality, and our attendant knowledges and attitudes are brought into play; only then does the aspect become meaningful in reference to it. The abstract shadow shape in a night scene is not understood at all until revealed and identified as a person; the bright red shape on a pale ground which might, in an abstract, graphic context, communicate a sense of gaiety, conveys something altogether different when recognized as a wound. As we watch a film, the continuous act of recognition in which we are involved is like a strip of memory unrolling beneath the images of the film itself, to form the invisible underlayer of an implicit double exposure.13

The elemental authority of the photographic image lends reality even to the most artificial events recorded by it.

A series of lectures she gave at a Woodstock, New York, summer workshop in 1959 (she was beginning to work on her haiku-inspired film then) began with the polemical statement, “Art must be artificial.” Her emphasis then, as always before, was on form. Twelve years earlier she had defined form:

Art is distinguished from other human activities and expression by this organic function of form in the projection of imaginative experience into reality. This function of form is characterized by two essential qualities: first, that it incorporates in itself the philosophy and emotions which relate to the experience which is being projected; and second, that it derives from the instrument by which that projection is accomplished.14

She finds it highly significant that the age which produced the theory of relativity produced in the film camera an instrument capable of synthetic constructions across space and time. Speaking of “the twentieth century art form” in her last theoretical essay, she raises a concluding question and answers it:

How can we justify the fact that it is the art instrument, among all that fraternity of twentieth-century inventions, which is still the least explored and exploited; and that it is the artist—of whom, traditionally, the culture expects the most prophetic and visionary statements—who is the most laggard in recognizing that the formal and philosophical concepts of his age are implicit in the actual structure of his instrument and the techniques of his medium?

If cinema is to take its place beside the others as a full-fledged art form, it must cease merely to record realities that owe nothing of their actual existence to the film instrument. Instead, it must create a total experience so much out of the very nature of the instrument as to be inseparable from its means.15

Her major essays all take shape through a series of negative reductions; she rejects the graphic cinema and animation for their refusal to accept the reality of the photographic image and for their use of painterly forms in film; she criticizes the documentary for its exclusion of the imagination and its passive dependence on accidental phenomena; and she calls the narrative cinema to task for its imitation of literary modes.

Nevertheless in each of these highly exclusionary essays, the dance creeps in as an acceptable part of cinematic synthesis. In “Cinema as an Art Form,” she makes this parenthetical observation:

(Dance, for example, which, of all art forms would seem to profit most by cinematic treatment, actually suffers miserably. The more successful it is as a theatrical expression, conceived in terms of a stable, stage-front audience, the more its carefully wrought choreographic patterns suffer from the restiveness of a camera which bobs about in the wings, onstage for a close-up, etc…. There is a potential filmic dance form, in which the choreography and movements would be designed, precisely, for the mobility and other attributes of the camera, but this, too, requires an independence from theatrical dance conceptions.)16

The longest and most interesting of her theoretical writings is the densest, An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form, and Film. Even the form of the book reflects her obsession with structures; here she brings together her views on science, anthropology, metaphysics, and religion with the attacks on the conventional modes of film-making which I observed in her other writings. In trying to define an aesthetic and ethical worldview, she launches into an attack upon Surrealism, which she finds as deficient as realism in providing images of human consciousness. “Consciousness” is her key word in this essay, and she approaches it historically, claiming that a fundamental change in human mentality took place around the seventeenth century. “In the course of displacing deity-consciousness as the motive power of reality, by a concept of logical causation, man inevitably relocated himself in terms of the new scheme,” she wrote in the opening section.

The Surrealists, according to her, hark back to a world before this absolute change.

Their “art” is dedicated to the manifestations of an organism which antecedes all consciousness. It is not even merely primitive; it is primeval. But even in this effort, man the scientist has, through the exercise of rational faculties, become more competent than the modern artist. That which the sur-realists labor and sweat to achieve, and end by only simulating, can be accomplished in full reality, by the atom bomb.17

She would have us bear in mind that the classicism of the early eighteenth century was a function of the shift from an absolute to a human ideal in the previous century. Furthermore she considers the psychological orientation and the cult of personality in contemporary art to be a degeneration from this successful period.

There is some discrepancy between her theory and her films. In the preface to the Anagram, she warns us of the danger of expecting a perfect continuity between them:

In my case I have found it necessary, each time, to ignore any of my previous statements. After the first film was completed, when someone asked me to define the principle which it embodied, I answered that the function of film, like that of other art forms, was to create experience—in this case a semipsychological reality. But the actual creation of the second film caused me to subsequently answer a similar question with an entirely different emphasis. This time that reality must exploit the capacity of film to manipulate Time and Space. By the end of the third film, I had again shifted the emphasis—insisting this time on a filmically visual integrity, which would create a dramatic necessity of itself, rather than be dependent upon or derive from an underlying dramatic development. Now, on the basis of the fourth, I feel that all the other elements must be retained, but that special attention must be given to the creative possibilities of Time, and that the form as a whole should be ritualistic (as I define this later in the essay). I believe of course that some kind of development has taken place; and I feel that one symptom of the continuation of such a development would be that the actual creation of each film would not so much illustrate previous conclusions as it would necessitate new ones—and thus the theory would remain dynamic and volatile.18

Her intense rejection of the cult of the personality, of the psychoanalytic approach to art, and of explicit symbolism ignores the privacy of the sources of Meshes of the Afternoon, At Land, and Ritual in Transfigured Time. That intimacy, which her films share with the painting of their time, although they share little else, is to their credit. When she moved further from the powerful element of psycho-drama, in Meditation on Violence and much later in The Very Eye of Night, her art diminished.

In the text she distinguished between imagery and symbolism:

When an image induces a generalization and gives rise to an emotion or idea, it bears towards that emotion or idea the same relationship which an exemplary demonstration bears to some chemical principle; and that is entirely different from the relationship between that principle and the written chemical formula by which it is symbolized. In the first case the principle functions actively; in the second case its action is symbolically described in lieu of the action itself. An understanding of this distinction seems to me to be of primary importance.19

But she interpreted imagery very literally if she could describe the footsteps on water, grass, pavement, and rug of Meshes of the Afternoon in this way: “What I meant when I planned that four stride sequence was that you have to come a long way—from the very beginning of time—to kill yourself, like life first emerging from primeval waters.”20

She makes an interesting connection between the quality of classical art and ritualistic form:

The romantic and the sur-realist differ only in the degree of their naturalism. But between naturalism and the formal character of primitive, oriental and Greek art there is a vast ideological distance. For want of a better term which can refer to the quality which the art forms of various civilizations have in common, I suggest the word ritualistic. I am profoundly aware of the dangers in the use of this term, and of the misunderstandings which may arise, but I fail, at the moment, to find a better word. Its primary weakness is that, in strictly anthropological usage, it refers to an activity of a primitive society which has certain specific conditions: a ritual is anonymously evolved; it functions as an obligatory tradition; and finally, it has a specific magical purpose. None of these three conditions apply, for example, to Greek tragedy.21

The ritualistic form reflects also the conviction that such ideas are best advanced when they are abstracted from the immediate conditions of reality and incorporated into a contrived, created whole, stylized in terms of the utmost effectiveness.22

Above all, the ritualistic form treats the human being not as the source of the dramatic action, but as a somewhat depersonalized element in a dramatic whole.23

In several other places Maya Deren refers to her art as “classical” and to her films as “classicist,” yet there is little to justify this description in her works unless it is the conservative quality of the dance movements or the occasional references to Greek myth.

Classicists looked on the arts of Greece and Rome as paradigms of logical and moral order. The revision of this perspective resulted from a late Romantic investigation of Greek irrationality, initiated by Friedrich Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music (1871), which affirmed the primitive and ritualistic elements in all the arts, using Greek tragedy as the pivotal example. In calling her art “classical,” Maya Deren seems to have wanted to point out the chastening of Dionysian elements in her employment of ritual. She also seems to have perceived that the American art of her time in painting, poetry, and potentially in film was deeply committed to an elaboration of its Romantic origins. By calling herself a classicist she was trying to disassociate her work from the excess of that tendency. The disassociation was never complete, nor did she want it to be. What she could not know was that in its future evolution the American avant-garde film would plunge into a dialogue with the major issues of Romantic thought and art and that the mythic inwardness of her early films would be used as springboards for that plunge.