THERE HAVE BEEN MANY collaborations in the history of the radical cinema. Before Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid made Meshes of the Afternoon, Dali and Buñuel had collaborated, as had James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber on The Fall of the House of Usher (1928) and Lot in Sodom (1933). René Clair, Francis Picabia, and Erik Satie joined forces to make Entr’Acte, which I shall discuss shortly. Film-making has been, and remains most often, a group activity, with specialized divisions of labor. It is not an extraordinary situation, then, when artists from other media, complaining of the poverty of imagination in existing films, set out together to make a virgin attack on the cinema. And it often happens that a writer or painter works with someone who already knows the mechanics of the camera and the editing machine.

At the end of the Second World War, film was a potentially fertile field for American visionaries. Maya Deren had made her first films, although few people were aware of them until late in the forties when she had begun to lecture and the two great film societies, Cinema 16 in New York and Art in Cinema in San Francisco, had been formed and showed them. It was possible, however, to see “the boiler plate of the Museum of Modern Art,” as Sidney Peterson called the widely distributed prints of Potemkin, Un Chien Andalou, Entr’Acte, Symphonie Diagonale, Rhythmus 21, and the numerous other classic films available from New York. These works opened up the area of cinema without establishing a constricting tradition for the artists who saw them.

When Peterson himself began to make films, he was fully conscious of the strategies of Buñuel and Dali. He applied them to his own situation. When he met the poet and playwright James Broughton, they agreed to collaborate on a play. They worked out an outline and began to write the dialogue together (it was to have been about John Sutter’s old age) when the project shifted into film. The play and its ideas were abandoned.

Peterson had shot some footage with a friend on a camping trip and had assembled it in his living room. This gave him sufficient knowledge of the mechanics to dare a more ambitious film. A discussion in Peterson’s house one evening in 1946 initiated the film. Four people were there, including Broughton and Peterson. One owned a small film company, another had some money. They decided to begin a film rather than just talk about one.

It was not long before the angel, unhappy in the role of sponsor, withdrew. The man with the film company lent equipment but stayed out of the project. With no money, they could only shoot one reel of film at a time. That meant one hundred feet—or about three minutes of film—during each session. Thus the shooting, spread out over three months, was highly discontinuous. That discontinuity was accented by the disappearance of the young man they had chosen as their protagonist.

Unlike Maya Deren, Peterson and Broughton preferred to use their friends as actors in their first films, not themselves. In their choice of a leading player they followed a tactic of Un Chien Andalou by selecting a type who projected a quality of madness. Shortly after the completion of the Dali-Buñuel film, Pierre Batcheff killed himself; not too long after that, the leading lady also killed herself. In the case of The Potted Psalm, Harry Honig simply disappeared after one shooting session. The rest of the film had to deal with this contingency.

From the reports of both creators, the collaboration went smoothly.1 Peterson operated the camera, and they both agreed on the choice of shots. When it came to the editing, they worked together “over one another’s shoulders” according to Peterson.

When the film was first shown during the initial season of Art in Cinema, Peterson wrote the following note:

The Potted Psalm was shot during the summer of 1946. The original scenario and shooting script were discarded on the first day. Thereafter fresh scenarios and scripts were prepared at least once a week for a period of about three months. The surviving film was cut into 148 parts and the parts numbered—one to one forty-eight. The scenarios then read like stock market reports.

This pullulation of literary material, finally taking a numerical form, was deliberate. What was already literary had no need to become cinematic. The resulting procedure corresponded to the making of a sketch in which, after an enormous preliminary labor of simplification, the essential forms are developed in accordance with the requirements of a specific medium.

The necessary ambiguity of the specific image is the starting point. From a field of dry grass to the city, to the grave stone marked “Mother” and made specific by the accident (“objective hazard”) of a crawling caterpillar, to the form of a spiral, thence to a tattered palm and a bust of a male on a tomb, the camera, after a series of movements parodic of the sign of the cross, fastens on the profile of a young man looking into a store window. All these scenes are susceptible of a dozen different interpretations based on visual connections. The restatement of shapes serves the general purpose of increasing the meanings of the initial statements. The connections may or may not be rational. In an intentionally realistic work the question of rationality is not a consideration. What is being stated has its roots in myth and strives through the chaos of commonplace data toward the kind of inconstant allegory which is the only substitute for myth in a world too lacking in such symbolic formulations. And the statement itself is at least as important as what is being stated. The quality, for example, of rectangularity in the maternal tomb is a primary consideration. Psychologically it constitutes a negation of the uterine principle. Aesthetically it derives its force from what has been called the geometric as opposed to the biologic spirit. The definition and unification of these opposing spirits is one of the functions of a visual work. Nor is it necessary for an audience to analyze these functions. It is enough to know that they exist. At least they may be presumed to exist. Having made the assumption, it is possible to go on from there.

Unfortunately, where we go is by no means certain. The replacement of observation by intuition in a work of art, of analysis by synthesis and of reality by symbolism, do not constitute a roadmap. It is perhaps wanting too much of art to expect it to perform the kinds of miracles ordinarily demanded of world statesmen. Not a roadmap possibly but the beginnings of a method. A method of statement, in a medium sufficiently fluid to resolve both the myth and the allegory in a complete affirmation.2

By design and by necessity The Potted Psalm evolves disjunctively; the various women of the film (there are six in the credits) form a virtually continuous spectrum from innocent girl to savage old lady, but at any given moment of the film it is difficult to tell the middle figures apart; the mixture of motifs and styles, which in later films are typical of either Peterson or Broughton, makes it difficult to bring the film into focus as a totality.

The overall plan is quite straightforward; a graveyard episode is followed by an interior scene and ends again outdoors near the graveyard. Brief exterior scenes punctuate the middle sections. At times the film seems to proceed narratively, though with radical ellipses, and at times it seems to be a thematic construction, cutting away from narrative time. The themes of schizophrenia and the bifurcated male, in addition to being an obsession of Peterson’s, fit the fact of the collaboration and its helterskelter method.

The film opens with a pan from deep weeds to a hilltop view of San Francisco. We are immediately confronted with a metaphor which determines much of the movement and montage of the film. Ever since this film, San Francisco has inspired avant-garde film-makers to portray it as a paradise of fools. Peterson himself, turned writer, spent a decade on a book about the philosophy and eccentricity of the city itself.

From the weeds, the camera sweeps sideways over a grave marked “Mother” while a snail or caterpillar creeps one way as the camera moves in the opposite direction. The camera settles on the granite head of a man carved on a gravestone. A cut shows us the protagonist’s face in a similar profile; his pimples are highlighted. His face twitches. Throughout this film almost everything else twitches—feet, thumbs, eyes—in a spasmic response to spastic construction.

He stands before a shop. When he looks in the window he sees, amid collected junk, a nude female figure, the first indication of the theme of adolescent sexuality which pervades the film. Shortly he makes his way to a house which might be a madhouse or a bordello, or both. Inside he undergoes a metamorphosis into a headless man in a navy jacket. There he sees an old lady eating the leaves of a plant; when he lifts the skirt of another woman seated beside him, he finds she has a carved table leg; later both her legs are of flesh, but the foot of one is stuck in a glass beaker.

Intercutting between this interior and the grave suggests that these madwomen or whores might be ghouls or that their house might open into the realm of death. Once he is inside, narrative causality disappears. The headless man pours a drink down his neck. In a closeup, someone picks at a plate of broken glass with a knife and fork. From the perspective of the subjective camera, a drink is drunk and a cigarette smoked as if the camera itself were consuming them. Other women appear and dance with the camera, which may stand in for the protagonist, and with a reflecting tube wearing a hat. One of the women kisses an anamorphic mirror. From that point onward, distorted and reflected images increase in frequency. The twitching, scratching, tongue flicking, and dancing accelerate as well. Eventually he flees from the house, and the semblance of narrative begins again.

Violence dominates the next images. The mannequin is broken and bloody. The hero, at times headless and at times the pimply youth, takes up a knife, kicks away the dead carcass, and cuts through meat, but only a snail falls away. Now we are back at the scene of the film’s opening, by “Mother’s” grave. From here a woman runs away in slow motion. The camera follows her, superimposing several images of her flight. The speed changes from very slow to very fast. Then, when she passes over a hill, the film ends.

In their subsequent films Peterson and Broughton draw heavily on the experience and material of The Potted Psalm, but with more successful formal organization. Perhaps that film, which was made on a lark, might have been its makers’ last were it not for its success at the opening season of the Art in Cinema film society. As a result of the near riot at its opening, Douglas MacAgy, then the director of the California School of Fine Arts, conceived the idea of including avant-garde film-making in the curriculum of his school.

At the end of the war the students of the art school, somewhat older than usual, tended to be more proficient than inspired. The film-making course offered more involvement in the experience of art-making. Peterson was hired to teach it. Each of the students paid a small fee for materials and to finance their collective film. Peterson used the situation with consummate skill to pursue his film-making. The films he made between 1947 and 1949, The Cage, The Petrified Dog, Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur, and The Lead Shoes were all workshop projects. In each of them the students acted, constructed sets, or supplied the basic themes.

The evolution of the first of these films, The Cage (1947), shows the vicissitudes of the situation in which Peterson found himself, but also his ability to turn it into an aesthetic triumph. To begin with, he engaged his friend Hy Hirsch as a cameraman. Hirsch had not yet made any of his own films, but he had experience with a motion picture camera, access to equipment, and a sincere interest in the project. Peterson decided not to operate the camera himself because he had to lecture while he was in the process of making the film.

Peterson’s talent lies in synthesizing. He begins with a few themes and a few stylistic principles. The film then emerges spontaneously. He shoots with the idea in mind that the structural cohesion of film comes in the editing. Looking at the whole of his work, we can see how he challenges his own aesthetic by providing himself with radically different components to synthesize. This becomes more obvious in the later films.

The Cage begins with a picaresque theme, the adventures of a loose eyeball. This was to be filmed “with every trick in the book and a few that weren’t.” He used all the camera times: slow, fast, normal, and reverse. Superimposition and stop-motion disappearances are employed. To these he added a few tricks of his own, such as a cut-out collage which moves to reveal the actual scene or the counterpoint of forward and backward motions (he filmed his actors running backward through a crowd and had the film reversed so the crowd runs backward and the actors forward).

He chose the student with the maddest expression as the protagonist. He could not have been very surprised, after the making of The Potted Psalm, when this schizophrenic-looking young man dropped out of school and deserted the film midway through shooting. Peterson employed the same tactic he had earlier: find a double and deflect the theme of the film. This time he could do it with more control.

He already had a shot of the first young man sitting on a chair, bent over thinking, with a patch on his eye. He put his new hero in the same position and then he dissolved the two shots within the camera, so that one blends into the other. A concave anamorphic image shows the two fusing together (achieved by joining two different images at the point of maximal distortion so that the clear image of the first blurs, and out of the blur comes the second). When, later, the second man wears the patch, the transfer is complete.

The construction of the film is so continuous that, unless told by the film-maker, the viewer could not guess that the film did not proceed completely according to plan. In its final version The Cage describes the adventures of a “mad” artist. In a symbolic or real self-mutilation, he takes out his own eye, which immediately escapes from his studio into an open field and then meanders through San Francisco. His blinding is accompanied by complete schizophrenia. He alternates with his double throughout the film.

His girlfriend, who is also his model, frightened by his mad groping around his studio for the lost eye, gets a doctor. The girl, the doctor, and one of the two protagonists then chase around the city after the eye. Throughout the film the perspective alternates between that of the pursuers and that of the eye itself. The eye’s vision is filmed through an anamorphic lens.

The strategy of the doctor is to catch the eye and destroy it. To save the eye, the double continually has to thwart the doctor’s attacks with darts and rifles. Eventually the eye is recovered, and the schizophrenic becomes the original young man. His first act as a reunited man is to knock out the doctor who otherwise would have ruined his recovery and, presumably, taken the girl.

In a deliberately parodic ending, the artist and girl walk off hand in hand. He embraces her in a field, and she flies out of his arms into a tree.

As the comparison of outlines would suggest, The Cage develops much of the material rehearsed in The Potted Psalm. At times the imagery coincides. We see a snail crawling over the eyeball, just as we had seen one repeatedly in the earlier film. In The Potted Psalm, the carcass, the eating of glass, and the cutting through meat function as visual jolts. They are reminiscent of the sliced eye in Un Chien Andalou. In The Cage the tactile horror is greater, though still not on a level with the Dali-Buñuel film.

The snail crawling over the eye; the eye rolling in the mouth of a sleeping man, or onto the hatpin of a shoplifter; the eye caught in a wet mop; these are all images that create a virtually tactile response. The most vivid of them, the hatpin, fuses horror and humor in the best surrealistic style.

The Cage also has within it a mad “city symphony” of San Francisco as seen from the rolling eye. When Peterson eventually gave up filmmaking and concentrated on writing, he published his novel, A Fly in the Pigment, elaborating on the picaresque adventures of the eyeball in The Cage. In the novel a fly escapes from a Dutch flower painting in the Louvre and explores the human comedy of Paris before dying by being accidentally slammed between the pages of a book.

The images and movements of the camera we see in The Cage are Peterson’s. Hy Hirsch executed them well, kept the focus, and balanced the darks and lights. There is nothing in the dozen later Hirsch films like the camera work of The Cage; it recurs in all of Peterson’s work.

To begin with, there is the anamorphosis, the lateral and vertical distortion of images emphasized by a twisting movement of the lens which shifts the axis of contraction and elongation. The distortions of The Potted Psalm seem to have been done with a mirror or a crude mask over the lens. With The Cage and thereafter, Peterson uses an optically distorting lens. The device is simple and had been attacked as too “easy,” yet Peterson used it more intelligently and creatively than any of the numerous other film-makers who have tried before and after him. In his films the anamorphic lens opens an Abstract Expressionist space. Even though structurally he related anamorphosis to various forms of madness, his distorting lens offers an alternative to haptic perspectives.

In The Cage the distorted imagery clearly represents the perspective of the liberated eye. After the eye is dislodged, it remains for a while in the room. The protagonist chases after it while all the furniture flies over and at him in slow motion. Peterson skillfully pivots the camera in a circular movement. The flying furniture and the spinning camera are intercut and subvert our gravitational orientation. The episode ends, effectively, with a reverse motion shot of the flying furniture as the floor and the eye are mopped up. The illusion makes the fallen chairs, tables, easel, and so on return to their places through the action of the mop.

Peterson attempted so many things that the film is much more interesting than it is successful. Yet where it is successful, as in the dialogue of perspectives and their spaces, it is breaking new ground for a subjectivist cinema. It is specifically his use of radical techniques as metaphors for perception and consciousness (which is intimately bound up with the Romantic theme of the divided man) that elaborates upon Deren’s central contribution and paves the way for future refinements of cinematic perspective in the avant-grade.

There is a section in the film where the dialectic is especially effective. Just after the eyeball floats out the window, there is a shot of the girl sleeping on the couch in the studio, fully dressed, with the doctor’s foot by her head. The double of the hero lifts his patch and we see, presumably, what he perceives: his alter ego rushing through the streets of San Francisco with a cage over his head. The people of the city all walk backwards; the cars too run backwards. Then the shot of the sleeping girl returns.

This small episode attracts our attention because of its ambiguity. In the first place, it suggests a dream; what follows, or perhaps the whole film, might be the vision of the girl’s afternoon sleep, as in Meshes of the Afternoon. Then, within the dream, comes the set of shots which suggests that the episode is the interior reflection of the double.

The bird cage which gives the film its title appears first just after the dissolve connecting the double protagonist. The first is wearing it over his head. From then on, until he is made whole again and his caged self is buried in the sand on a beach (reverse motion), he wears it as a symbol of his schizophrenia. Obviously these scenes were shot before the theme of the alter ego entered the film, since it is the actor who disappeared who wears the cage. The specific use of the symbolism is simply a result of the film’s ultimate construction. Here then is the clearest example of the process of film creation that Peterson described in his note to The Potted Psalm.

The second appearance of the cage comes at the end of a wild camera movement during the first scramble after the rolling eye when the cage lands on the head of a statue, that persistent archetype of the early avantgarde film. The statue emerges in the most ambitious subjectivist films as a desperate surrogate for basic human needs.

A discussion of The Cage would not be complete without referring to Entr’Acte (1924), the exemplary film of the Dada movement. Entr’Acte stands in the same relationship to The Potted Psalm and The Cage as Un Chien Andalou does to Meshes of the Afternoon. Its conception resembles that of Peterson’s collaboration with Broughton; as a finished film, it is more like his first solitary exercise. The ways that they differ point up the differences between the American avant-garde film of the 1940s and the French of the 1920s.

Entr’Acte was made to be shown between the acts of a ballet, called Relâche, or No Show Today. The negative titling was the work of Francis Picabia, the Dadaist painter, who wrote the film scenario and made the sets for the ballet itself; Erik Satie provided music for both. When he decided that the performance should have a filmed curtain raiser and a movie intermission, the task of production was given to René Clair.

Clair modestly describes the circumstances: “When I met him he explained to me that he wanted to show a film between the two acts of his ballet, as had been done, before 1914, during the intermissions of café concerts. And since I was the only one in the house involved with the cinema, I was called upon.”3 There is no reason to doubt him. For Picabia the film was a casual affair. He jotted down the most schematic of scenarios on stationery from Maxim’s. One can imagine him writing as he finished his coffee:

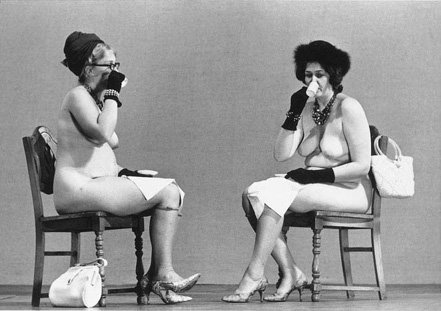

The cage as an icon of the discontinuity of the self: Sidney Peterson’s The Cage; Anais Nin in Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome.

At the rising of the curtain: cannon charges in slow motion performed by Satie and Picabia; the shot will have to make as much noise as possible. Length: 1 minute.

1. Boxing assault by white gloves, on black screen: length 15 seconds. Written slide for explanation: 10 seconds.

2. Chess game between Duchamp and Man Ray. Waterspout maneuvered by Picabia sweeps over the game: length 30 seconds.

3. Juggler and Père Lacolique: length 30 seconds.

4. Hunter shooting at the egg of an ostrich on waterspout; a dove comes out of the egg and lands on the hunter’s head; a second hunter shooting at it (the head) kills the first hunter: he falls, the bird flies away: length 1 minute. Written slide 20 seconds.

5. 21 persons lying on their backs, showing the bottom of their feet, 10 seconds, handwritten slide 15 seconds.

6. Female dancer on transparent glass filmed from underneath: length 1 minute, written slide, 5 seconds.

7. Blowing up of balloons and rubber screens, on which figures will be drawn along with inscriptions: length 35 seconds.

8. A funeral: hearse drawn by a camel, etc., length 6 minutes, written slide 1 minute.4

Satie was more meticulous; he pressed Clair for a shot by shot breakdown of the finished film, with timing, so that he could carefully synchronize a score for it. This was before sound projection, and the orchestra of the ballet played along with the film.

Clair had a free hand. The artists named in the scenario all played their parts. He omitted the third and fifth sections, and freely improvised on the sixth and eighth.

Two years after the ballet, Entr’Acte went into distribution without sound and with the curtain raiser attached to the front of the film as a prologue. That was how Peterson and Broughton first saw it. In this form the film opens with a cannon moving by itself around the roof of a building in Paris. In slow motion, Satie and Picabia leap into the frame. They discuss a plan, which at first shocks Picabia, but he soon agrees to fire the cannon into the buildings where Satie has pointed. They do it. Then they fire it in the direction of the camera and audience.

A series of superimpositions establishes the roofs of Paris, while images of balloon dolls being inflated and a ballerina, seen from below dancing on a glass floor, are intercut.

The flames of matches dance in superimposition in the hair of a man whose face cannot be seen. He scratches his head, then lifts it, revealing surprised eyes. Repeatedly throughout this scene and through most of the film we see glimpses of the ballerina, until a change of camera angle eventually reveals her not to be a ballerina at all, but a bearded man dressed as one.

An offscreen jet of water ruins a game of checkers, played by Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. Then, after a series of superimpositions involving water, a paper boat, and the pseudo-ballerina, we see an ostrich egg held in the air by a vertical jet of water. A hunter spots it, but every time he lifts his rifle, the egg multiplies into two, four, eleven dancing eggs. Finally it becomes singular again, and he fires. To his happy surprise a pigeon falls from the sky and lands on his head.

Picabia, on a nearby roof with a rifle, has spotted the hunter with the pigeon on his head. He tries to shoot the bird off, but he kills the man instead. The scene jumps to his funeral. Yet the water still holds up the egg and the dancer dances. A ridiculous burial procession is led by a cameldrawn hearse. As they pass an amusement park the hearse comes loose and the whole party, including the widow and numerous old men, chase after it. As the hearse picks up speed, the camera movements become wilder and scenes from a roller-coaster are intercut with the chase.

Eventually the coffin flies off the hearse, rolls through a field, and pops open. Out comes a stage magician. With his magic wand he makes the assembled mourners disappear; then he performs the same trick on himself.

When the title “Fin” appears, a man jumps through the paper upon which it is written; then the shot is reversed so that he leaps back, the paper mends its rip, and the film ends.

In its round-about manner of narrative, its slapstick chase, its exploitation of camera tricks both as metaphors and as developments of the “plot,” and the comic violence of its shooting scenes, Entr’Acte prefigures The Cage. It anticipates The Potted Psalm, on the other hand, with repeated interruptions of the picaresque development by fragments of continuous scenes which bear no direct relation to the main chain of events. Behind all three films, of course, lies the comedy style of Max Sennett.

The differences among Entr’Acte, The Potted Psalm, The Cage, and the slapstick comedy are more interesting than their similarities. The avantgarde films which owe their inspiration, in part at least, to slapstick comedy tend to exhibit a shift of rhythm away from comic punctuation (for the humor of the great film comedians is a rhythmic function) toward the abstract. This displacement reveals the irrationality and the unconscious dynamic behind the previously funny archetype, the chase. In an effective silent comedy there is no time for metaphors. The comic film-maker can only deviate from the main line of comic action when the point to which he deviates extends the humor by prolonging it. The periodic recurrences of the pseudo-ballerina in Clair’s film relieve the tension of the funeral chase.

Yet when we compare Entr’ Acte with either The Potted Psalm or The Cage, it seems a much more comical film. Satire was the film-makers’ inspiration. Remember the circumstances which motivated its creation: the bearded ballerina mocks the expectation of a ballet audience, and the members of the funeral procession mock the audience itself. In the prologue and in the murder of the hunter, Picabia and Satie flippantly disregard the most potent taboo of modern times—murder for its own sake. In the same spirit of provocation, Satie had announced that his music for the ballet would be “pornographic.”

In The Potted Psalm and The Cage, the slapstick sources are at a greater remove. Everything moves in an aesthetic direction. The filmmakers of the 1940s in America, unlike their Parisian predecessors, were not mocking the sacred cows of the bourgeoisie. The Second World War had obliterated much of what Picabia was attacking. In the films Peterson made, either as collaborator or sole maker, what had previously been social is made aesthetic.

Broughton, however, had a more classically comic sensibility. While Peterson’s humor resided in his sense of the irrational and in the collision of ideas, Broughton’s focused on character. The childlike man is Broughton’s favorite metaphor. “Mother’s” grave, the bordello aroma of the interior scenes, and a shot of the hero on a kiddymobile must surely have been among Broughton’s contributions to The Potted Psalm.

In an interview with the author Peterson remembered how Broughton used to roar with laughter at the rushes of the film, while he was, if anything, disappointed. But when the editing was completed it was Peterson who felt the magic of the whole, while Broughton was apprehensive. Peterson was the synthesizing Surrealist; Broughton, the comedian of archetypes. His humor turned on the universal rather than the peculiar; the emblem he took for himself, and wore on a stickpin, is the alchemical sign for essence.

In 1948 Broughton made his first film by himself. He employed a cameraman (in this case, Frank Stauffacher) as he did on almost all his subsequent films. Broughton’s experience, aside from The Potted Psalm, had been as a poet and playwright. It is out of his early plays and poems that the theme of this first film, Mother’s Day, emerged.

His own notes are an articulate introduction to the film:

From the beginning I accepted the camera’s sharply accurate eye as a value rather than a limitation. The camera’s challenge to the poet is that his images must be as definite as possible: the magic of his persons, landscapes, and actions occurring in an apparent reality. At this point something approaching choreography must enter in: the finding of meaningful gesture and movement. And from the beginning I decided to make things happen head on, happen within the frame, without vagueness, without camera trickery—so that it would be how the scenes were made to happen in front of the lens, and then how they were organized in the montage, that would evoke the world I wanted to explore.

The subject matter of Mother’s Day cannot, certainly, be considered specialized. Most of us have had some experience of childhood, either by participation or by observation. But do we remember that children are often incomprehensibly terrorstricken, are always ready to slip over into some private nonsenseritual, or into behavior based upon their misconception of the adult world? Furthermore, what about the “childish behavior” of grown-ups, their refusal to relinquish childhood misconceptions, or to confront the world they inhabit?

Although this film is, then, by its very nature, a nostalgic comedy, it eschews chronological accuracy in either the period details or the dramatic events. It has been one of the clichés of cinema since the days of cubism that the medium allows the artist to manipulate time: to cut it up, retard or accelerate it, and so forth. In Mother’s Day historical time may be said to stand still. Periods and fashions are gently scrambled. The device is deliberate: for with this film we are in the country of emotional memory, where everything may happen simultaneously.

This is because the basic point of vision of the film is that of an adult remembering the past (and the past within the past): projecting himself back as he is now, and seeing his family and his playmates at his present age-level, regarding them with adult feelings and knowledge, and even projecting them forward into his present-day concerns.

In Mother’s Day I deliberately used adults acting as children, to evoke the sense of projecting oneself as an adult back into memory, to suggest the impossible borderline between when one is child and when one is grown-up, and to implicate Mother in the world of the child fantasies as being, perhaps, the biggest child of them all—since she, in this case, has never freed herself from narcissistic daydreams.

Since this is a film about mothers and children, about families and forms of social experience, it is dominated by the circle, and—as Parker Tyler pointed out—by the object revolving on a fixed axis.5

A series of six ironic subtitles divide the sections of the film. It opens with a young man sleeping in the arms of a statue, an evocation of the opening of Chaplin’s City Lights, and another instance of this ubiquitous motif in the early American avant-garde film. Then we read “Mother was the loveliest woman in the world. And Mother wanted everything to be lovely.” A number of brief, enigmatic shots follow in what the film-maker calls a “formal prelude.”

This basically abstract passage introduces a number of typical elements in the film without explicitly delineating the main ironic structure. The impression of an animated family album, heightened by the nostalgic music of Howard Brubeck, written for the film, is immediately apparent. In this brief passage, the mother has at least four changes of costume. In the remainder of the film there is a minor or major change of this sort in nearly every one of her appearances on the screen. These changes involve an intentional mixture of periods and styles. At one point in the prologue gauze in front of the camera modifies the image.

The effect of the alternations of costume, the short shots, the occasionally unusual angles, and the gauze is to create a scintillating image which seems to weave randomly through time. The music, the rhythmic intercutting between images, and the concentric movements within the frame—such as the spinning medallion—give a fluid cast to the continuous metamorphosis. The dialectic of tensions, the smooth rhythm, and the staccato imagery make for formal strength which is reinforced by a play on scale and foreshortening related to the dominant themes of the film. The montage in the ruins of the building uses depth and angles to suggest the dominance of the female over the male.

In the next section, entitled “Mother always said she could have had her pick,” foreshortening makes the same statement. We see Mother at her upstairs window, shot from below to magnify her stature. Her suitors, filmed from high above, are diminished by the perspective of the camera.

The first shot of this episode is as brilliant an example of both metaphor and ellipsis as can be found anywhere in the avant-garde film. The camera pans up the stairs of a wooden house to its façade, at which moment we see that the house has been destroyed. There is only the façade. Next we see Mother smiling from the second-story window of a different house. The montage simultaneously suggests that Mother’s house is now destroyed (in other words, the ruin is proleptic), and that Mother herself is a façade (a visual metaphor). This is a rather simple example of cinematic prolepsis. In its more radical employment by Broughton in Dreamwood and by Brakhage and Markopoulos in several films, a shot may first seem to function in a simple relationship to the previous shots and only later, sometimes much later, is it grounded in a context more appropriate to its manifold aspects.

Broughton constructed the entire episode around the image of Mother scanning her suitors from the window. In each of her appearances, as I have mentioned, she changes a hat, an ornament, or her dress. The use of ellipsis is extreme and highly original. First, one suitor presents himself. We see mother from below; when the camera cuts back to the suitor, there are now two of them, holding gifts. The exchange continues until there are four. At the end of the sequence, there is a man in her room.

With the changes of shots in the interior scenes, there are changes of background comparable to the alternation of costumes. The sets themselves are in the theatrical tradition: screens, plants, pictures on the walls; a minimum of objects and furniture necessary to give the impression of a cluttered, turn-of-the-century interior. The basically static camera creates a sense of composition-in-depth out of these stage backgrounds. Mirrors are frequently used. In the third episode, “And she picked father,” we see the bearded father for the first time, reflected in an oval hand mirror into which Mother had been looking as she combed her hair. He is next seen, with his eyes bulging, posed in a frame on the wall as if he were a portrait.

The image, at the end of that section, of her playing with a doll introduces the next part, “Then Mother always said she wanted little boys and girls to be lovely.” We see her children. Although they are grown up, they play the games of children. In this and the remaining two sections of the film, the concentration on Mother is gradually replaced by that on the children. The progress of their games involves disguised rituals of the passage into adolescence. At the same time, their satiric mimicry of their parents reflects the adult world. As Broughton pointed out in the note I have quoted, the use of adults to play children is not solely ironic; it recreates the psychological superimposition of the past and childhood upon the adult.

In their games, each “child” plays alone, though several may appear simultaneously in a single shot. One waves her dolls; another devours a box of candies; another chalks a naked lady on the wall. They tease, fight, and cry. While they play, Mother stays at her dressing table, and the father, with his straw hat on his knee, watches them impatiently, tapping with his cane. The elements of this section are held together by a strong internal rhythm created by the tapping cane, the moving swings, a bowling pin rolling in water, and hopscotch steps—all in time with each other and with the music.

The thought or sight of the children makes Mother envision her old age. In the first shot of the next episode, “Because ladies and gentlemen were the loveliest thing in the world,” we see the face of an old lady who whispers to a man, so that the children cannot hear. But they have their own party. We see a homely girl sitting on a couch with a man. Another girl enters the room. Then we see the first one on the same couch with two men. The very same entrance shot is repeated four times. In each instance another man joins the girl on the couch. Thus the children use a parody of Mother’s courtship for their own sexual initiation.

The sixth and final title, “And so we learned how to be lovely too,” completes the ironic definition of loveliness. In a series of flashes, six bowls, each larger than the previous one, appear on the screen with a tapemeasure indicating their diameters. Like the spinning medallion, and later the spinning mandolin, they are hermetic images. These can be taken as metaphors for growth, to be sure; their function in the film is primarily irrational, rhythmic, and textural. They recall a sequence in The Potted Psalm, in which a nut is cracked and bread is broken in rapid succession. The sudden and unexplained deployment of a series of close-up details enriches the texture of Mother’s Day by intensifying its unpredictability.

The last episode begins when Mother leaves the house for a ride in an antique car. The children symbolically take over the house. A girl tries on her mother’s hats; a boy, his father’s. The straw hat is destroyed. They pull off the father’s beard. Out of a window fly the straw hat and the cane. Finally we see the living portrait of the father, only now upside-down. The mother, seen as usual at her mirror, is “left behind in a empty room, still dressed to go out but with nowhere to go” (Broughton’s note).

The inventiveness of Mother’s Day has had no imitators and therefore little influence on the subsequent development of the avant-garde film in America. It remains a unique cinematic object without predecessors or heirs. Simpler films by Broughton, with less radical formal ambitions, have had more influence; Christopher MacLaine, in The End, made a black version of Four in the Afternoon, and Ron Rice extended Loony Tom, the Happy Lover into The Flower Thief, though neither were aware that they were so close to Broughton. Broughton’s intense interest in comic types turned his film away from the trance film inspirations in a way that neither he nor his critics could see at the time. The trance film was predicated upon the transparency of the somnambulistic protagonist within the dream landscape. The perspective of the camera, inflected by montage, directly imitated his consciousness. Broughton invested too much in the individuality of his protagonists and too little in the cinematic representation of perception to contribute substantially to the trance film. It was only much later with the making of Dreamwood (1971) that the debts to Cocteau and Deren, which he had always readily acknowledged, surfaced visibly in his work. Even when he touched upon psycho-drama by playing the chief role in his second film, a version of the quest for sexual self-discovery so central to the early American avant-garde film, he saw himself with such irony, and so clearly as a psychological type, that The Adventures of Jimmy (1950) is as far from Fireworks, Swain, or Flesh of Morning—the psycho-dramas of Kenneth Anger, Gregory Markopoulos, and Stan Brakhage—as Mother’s Day was from The Cage or Deren’s films.

The Adventures of Jimmy is an autobiographical picaresque in which a mountain boy looks for companionship in the big city. The episodes are highly elliptical. Jimmy climbs into a canoe on a small stream in one shot and finds himself in a busy bay in the next; he wanders into a boarding house looking for a room and is followed by a prostitute, only to rush out and away, comically horrified, an instant later. In rapid succession he seeks love in an artist’s rendezvous, a dance hall, and a Turkish bath; he tries religion and psychoanalysis.

With every episode he changes his hat, from farmer’s cap, to sailor’s crew, to underworld fedora, to a ceremonial top hat. The last is the emblem of his final solution, marriage, as he walks out of church with his bride.

The irony, the ellipses, the symbolic changes of costume, that we found in Mother’s Day, recur here. Yet they are less ironical, less elliptical, and the transformations not as radical. But above all, the difference between the two films lies in their respective rhythms. The former is as calculated and modulated as the latter is casual.

By the time that Broughton made this film, Peterson, now deeply involved in the use of sound in cinema, had made his last avant-garde film,6 although he probably didn’t realize it at the time. In 1948 and 1949 he produced three sound films with his Workshop 20 at the California School of Fine Arts, the last two of which are his greatest achievements. The Petrified Dog, Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur, and The Lead Shoes were made in successive semesters as group projects with student participation.

The Petrified Dog takes its title from the statue of a lion seen repeatedly throughout the film and from an allusion to the freezing of the camera’s motion, which we see first in the background of the film’s titles. In theme, it might be called the further adventures of Alice in Wonderland. The heroine Alice climbs out of a hole in a park with her characteristic broad Victorian child’s hat into a world where we have already seen a painter working within an empty frame, a slow motion runner hardly getting anywhere, a lady in fast motion eating her lipstick, and a photographer who sets his camera up with a delayed shutter so that he can stand on pedestals and be snapped as a statue. Into this Wonderland she crawls, in slow motion at first.

The events of the film are essentially disconnected. We see them in the order in which Alice, continually blinking (as the hero of The Potted Psalm continually twitched), turns her shutter-like gaze on them. Like Maya Deren’s first heroine, she also sees herself in the mad landscape. The sole example of distorted imagery in this film is a brief shot of Alice looking at her reflection in the hubcap of a car. Peterson operated the camera himself this time. He eschewed the dynamic movements that characterize all his other films except for a few timid pans and some brief moving shots of the lion statue, both normal and upside-down. The stasis of the camera functions organically within the film: there is a sense that the episodes and gags are eternal, contiguous realities, not progressive events, and the camera style emphasizes the discreteness and fixity of the separate scenes, while the use of slow and fast motion brackets them.

I have deliberately neglected the climactic scene of the film. A terrified young man wanders over a statue of Abraham Lincoln and into a massage parlor where two men are fighting; a skeleton decides to take advantage of him, prone on the massage table. As the skeleton wrestles with him and possibly rapes him, in normal and slow motion, the camera is liberated from its tripod and joins in the frenzy. From this point on, the episodes show signs of internal development. A bum approaches the painter with an empty frame, sticks his head through, and demands a hand-out. When the artist finally pulls a full cup of hot coffee out of his pocket, the bum is thankless; he throws it down and he kicks it away. The lipstick-eating lady eventually finishes her pasty lunch and walks away dropping several handkerchiefs. The painter follows her, collecting the droppings, which eventually include a bra and a slip. He pursues her through her door, only to be thrust out and attacked by her husband. Alice also sees herself in a chase: she eludes her nanny.

The most interesting episode in the film is the one involving the painter and the bum, and it is interesting precisely insofar as it alludes to the art of René Magritte. The empty frame which makes a painting out of what-ever rectangle of reality it faces recalls a number of Magritte paintings in which a canvas, resting on an easel fixed in a landscape or interior, transfigures, in an illusionary way, the space in which it is placed.

(a) The surrealistic frame in Peterson’s The Petrified Dog.

(b, c) Anamorphic images in Sidney Peterson’s The Cage [the protagonist removes his eyeball] and Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur [dancing on the mattress].

If there is a single theme which pervades the early American avantgarde film, it is the primacy of the imagination. In Peterson’s films this theme is wedded to his own interest in the irrational sensibility of the artist. Yet despite the shift from the anarchistic themes of Entr’Acte to the psychological and aesthetic themes of Peterson’s first three efforts, those films are closer to the sensibility of Dada than Surrealism.

The sound track of The Petrified Dog is a primitive, and early, example of musique concrete. Peterson used four nonmusicians, a couple of traditional instruments, including an open piano so that the strings could be plucked or beaten, and anything at hand, even slapping oneself before the microphone of Hy Hirsch’s wire recorder. After a few run-throughs, they recorded the entire soundtrack in one long take. Clyfford Still, who was also teaching at the California School of Fine Arts, was so taken with the music that he offered to pay for the transfer to film if he could have a copy of the wire recording.

The soundtrack of The Petrified Dog is as free and as wild as the camera movements of Peterson’s two earlier films. It is also functional within the experience of the film. The problems of the formal use of sound in film (synchronism, asynchronism, montage, or picture with sound) have no place in a discussion of The Petrified Dog. There have been two consistent approaches to sound within the American avant-garde: the functional and the formal. The extreme formal position, which Stan Brakhage propounds and Peter Kubelka practices, and which we shall consider in detail in the portions of this book devoted to their works, holds that no sound should be employed in a film except where it is absolutely necessary, that is, where the film has been conceived as a careful audiovisual synthesis. The functional position rests on the assumption that music (or words) intensify the cinematic experience, even when the film has been shot and edited without consideration for the sound. The functionalist hires a composer after his film has been edited; at his most casual, he finds a piece of recorded music that “fits” his work. In the catalogue of Art in Cinema (1947), considerable space is devoted to the editors’ researches on the original musical soundtracks for many early French and German avant-garde films, and when research produced no results, they suggested a record which they had found, by experimentation, “fit” the older films.

Broughton and Peterson had asked Francean Campbell, a relative of the man who first lent them a camera, to compose music for The Potted Psalm. They did not like the result; they never used it. Peterson noted in his discussion of this experiment that a soundtrack was not necessary then because Art in Cinema (the only place where they conceived the film could be shown) had been so active in finding records to play with silent films. It is true that live or recorded music usually accompanied the silent avantgarde films when they were shown in the 1920s. But the difference between the speed of projection at that time (between 16 and 18 frames per second) and the speed standardized in 1929 for sound (24 frames per second) made it next to impossible to put sound on those films even after the invention and popular use of optical soundtracks. The distribution of early silent films through the library of the Museum of Modern Art created a new aesthetic of silence within the American film experience. Thus Maya Deren made her first three films intentionally silent, as Brakhage has made most of his films since 1958.

As collaborators, and later separately, Peterson and Broughton began with a functional conception of sound and moved toward a formal one. (Broughton returned to using a composer in the 1960s.) In both cases the formalization of the soundtrack occurred through a displacement of narrative information from visual images to voice, resulting in an elliptical treatment of the montage and an oblique method of conveying essential information through poetry, songs, or a stream-of-consciousness monologue. The simultaneous displacement of the narrative principle in both sound and picture necessarily provides for a new synthesis in their combination and for the possibility of a formal interplay through asynchronism, as one anticipates or reiterates the other.

It was Peterson rather than Broughton who made the most of these formal possibilities. His step toward the integration of the visual and the aural coincided with the development of his general conception of cinematic structure. Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur and The Lead Shoes recall the complex fusion of trance film, myth, and allusion in the kind of spherical mould that we found in Maya Deren’s Ritual in Transfigured Time. Peterson has an irony that Maya Deren totally lacked; these two films are more mandarin, more allusive than hers.

The elements of Peterson’s synthesis in these films are easily isolated: for Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur they are Balzac’s story, Le Chef d’Oeuvre Inconnu, Pablo Picasso’s engraving Minotauromachie and a monologue in James Joyce’s style. The visual unification is achieved simply and elegantly by the nearly absolute use of anamorphic photography and either fluid camera movements responding to the movements of the actors or almost choreographic movements of the actors within the static frame. Slow motion, especially at the beginning of the film, contributes to its gracefulness. There is almost no fast motion, superimposition, or wild movement of the camera. Peterson operated the camera himself.

The film-maker treated Balzac’s story as the framework for continuing his investigation of the artistic sensibility, which had been the theme of all of his earlier films. It was a theme especially suited to the situation out of which these films emerged—a workshop designed to infuse somewhat uninspired painters and sculptors with excitement about making art through a collective film-making experience.

Balzac’s short story, from his Contes Philosophiques of 1831, involves two real painters of the seventeenth century and one imaginary one. The mature Porbus and the novice Poussin meet Balzac’s creation, Frenhofer, who subjects Porbus’ latest work to a scathing critique, shows him how to bring life and depth to it with a few brush strokes, and then proceeds to tell them about the masterpiece he has been working on for the past decade, La Belle Noiseuse, a portrait without a model of the courtesan Catherine Lescault. They are desperate to see the work in progress. Frenhofer refuses to show it.

Porbus conceives a plan for bringing Poussin’s beautiful young mistress to Frenhofer as a model so that he may compare perfect living beauty with his idealization. This had been Frenhofer’s dream, and after much persuasion Gilette is talked into modeling for the old master. Shocked when he finally sees the picture, Poussin cannot help exclaiming that there is nothing there but a wall of chaotic colors and formless masses. All the two painters can see on the other’s canvas is a foot, an absolutely perfect realistic foot buried beneath the accumulated revisions of the painting.

For Balzac, there is no question but that Frenhofer in his Pygmalionlike desire to perfect his idealized women has obliterated his masterpiece. The thrust of the story, in any case, is not only aesthetic but moral: a parallelism and antithesis between the love of Gilette for Poussin and of Frenhofer for his painting, between the model in the flesh and the illusion on canvas, and ultimately between a man’s work and his love.7

Peterson transferred the character of Gilette from an innocent and devoted mistress to a garrulous, flighty art student; the reluctance and foreboding of the original become the narcissistic fantasies of the woman in the film. If we could consider the film without its soundtrack, it would be elliptical, involuted, and schematic. The interior monologue, which has subtleties and reversals of its own, provides the narrative coherence.

The anamorphic imagery congests the space, isolates the images, and suggests the realm of dream, memory, or a visionary state. The opening distortion of a cat with a dead mouse, followed by the slow fainting scream of Gilette accompanied by a violin whine, sets the tone for the whole film. It is one of several framing devices which initiate a dialogue of perspectives within the work.

There is a fade; the brief image of a fencer; and then we are thrust into the middle of a scene complicated by the beginning of an interior monologue of associations. Gilette and a young man (Poussin) are dancing in slow motion on a mattress. The hand-held camera, gracefully following the bouncing of the bodies and the swaying of the hem of her dress, accents the erotic metaphor. A change of camera distance reveals that an old man (Porbus) has been watching their dance. Poussin formally introduces him, and he kisses Gilette’s hand. They dance together on the bed. Another shot of the fencer, followed by a little girl carrying a candle (two images based on Picasso’s etching), marks the transition from this scene to the next.

In that scene, on the same bed and without the men, Gilette repeatedly pets her cat, intercut with recurrent images of the two figures from the Minotauromachie. These parallel scenes remain independent of each other, never appearing in the same frame, until the climax of the film. Yet in the monologue the elements from Balzac and Picasso are intertwined from the beginning. As she plays with the cat, she speaks the following monologue:

So much for nature mortified. And it doesn’t run very deep anyway. Better never than too early. It’s ever a question of how or ever. And no wonder the tired eye is a bird who sees something worked over for ten years. And no wonder too, it’s a plot to bribe the mater so chere with a modele, so to louvre to then chef d’oeuvre. And in this dream I too, caught like a spittle girl, immersed all in a stirry, a silly story: to pose or not to pose. I love him; I love him not. Or rather, since I love him less, already, why not?

An old man, mad about paint, Frenhofer and Gilette, boquet and med, me and Minotaur. Cats are carnivorous. Somewhere there lies a man’s head and the leftover part of a bull. God save us. Was that really a threat to Greek maidens?

The introduction of elements from the Minotauromachie occurs gradually. The minotaur itself, like Picasso’s, obviously a man with a beast headpiece, enters while Gilette is petting her cat. Poussin has come to visit her, to sit with her on the mattress, and to read aloud to her from a book, Balzac’s Le Chef-d’Oeuvre Inconnu. Although we have already seen in schematic form and heard in fragmentary allusions almost half of the story, the reading begins at the beginning, in Gilette’s voice. “On a cold December morning in the year 1512, a young man whose clothing was somewhat of the thinnest. …”

The narrative returns to stream of consciousness (“Why not? Ham on rye, cheese and salad. If I’m ruined it’s a question of pride or games. There’s nothing in it for him. If he showed his wife, it’s because he loved her not in order to see something better. Or because”).

By this point in the film, the images of the Minotauromachie occupy as much screen time as those from the story, and subsequently the proportions shift in favor of Picasso-like material with the narrative elements coming to function as an interruption of the etching come to life, just as the fencer and the little girl had previously been formal interruptions of the story. A contrast is established between the fast motion, jump-cut, repetitive runs up and down a ladder by a new figure, a man in a loincloth, and the lady in the window calmly petting her dove.

The last six shots of the sequence I have been describing bring the two worlds of the film’s title together. A lunge from the fencer strikes Frenhofer in the heart. He falls to the ground and the fencer wipes the blood from the foil. Just before the last image of the dying painter’s head, Peterson shows the Minotaur looking at the miraculous canvas, which of course we never get to see. The death occurs without a passage of monologue or reading.

Balzac’s portrayal of the death of Frenhofer is an appendix to his story; it is the pitiful conclusion to a tragedy of failure. For Peterson and for us, after the experience of the past century of painting, Frenhofer’s canvas is not a failure but a prophecy. The climax of the film—the death of the artist—calls up the myth of Pygmalion and invokes in explicit terms the central theme of the visionary cinema: the triumph of the imagination.

It is not the artist who brings his work to life, although that is his aspiration as reflected in the paraphrases from Balzac in the monologue: “Where is art? It’s absolutely invisible. It is the curve of a loving girl, and what fields of light! what spirit of living line that surrounds the flesh and defines the figure, that stands out so that if you wanted to you could pass your hand along the back.” It is the work, represented by the elements of the Minotauromachie, that engulf the man.

The elements of Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur gravitate toward the idea of abstraction. By choosing to incorporate a painting from Picasso’s classical period, rather than, say, an example of analytical Cubism, Peterson approaches the prophetic facet of Frenhofer’s painting through indirection. In an interview he described his intention:

It was my decision to do a thing about the Balzac story, taking seriously as the theme of the story the conflict between Poussin’s Classicism and its opposite. So as strained through my mind it became, really a way of exploring the conflict stated in Rousseau’s remark to Picasso: “We are the two greatest painters: you in the Egyptian manner; and I in the modern.” In a sense. [I was] taking the quest for absolute beauty in the Balzac character and contrasting that with Picassoidal Classicism, the imitation of the Minotauromachie. It was not necessarily thought out clearly as though one were writing an essay; this was thematic material. Then the chips fell, partly again, in response to the curious limitations of doing this kind of thing with people who were not even “anti-actors.”8

Peterson provides the material for a dream-like interpretation of the whole film. The opening and ending sequences contribute to the circularity of a dream; Gilette’s trauma of seeing her cat with a dead mouse may become, in the dream, an image of the minotauromachia (scratching the cat, she calls him, “mini-mini-mini-tower”). By another train of association, reflected in the monologue, she connects “Kitty” with Catherine Lescault of Balzac’s story, which her lover may have read to her.

Peterson was never completely satisfied with Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur because he had originally conceived of a more serious rendering of the monologue. He tried it himself, but found the recording incomprehensible. The woman who eventually recited it was perhaps too glib and heavy of emphasis for Peterson’s liking, but in his intimation of the film’s failure, he ironically impersonates his protagonist.

When the magazine Dance Perspectives published a special issue on dance in film, Peterson contributed a characteristically witty article. He begins with a reference to slow motion, more revealing of his Workshop 20 films than his attempts at filming dance:

So far as I know, no one has ever shot even a fragment of ballet at 100,000 frames per second, even though by this simple device one minute of shooting would be extended to more than 69 hours of performance. It would be like watching the hour hand of a clock move. The only possible audience would be the performers themselves, and not even the most narcissistic would be able to take all 69 hours.

I mention this fantastic possibility only because slow motion has, almost from the beginning, been the most obvious technical device (instant lyricism) for producing results that have gratified dancers and pleased cameramen.9

In Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur slow motion, along with anamorphosis and ellipsis, solves the problem posed by bad actors. The dancing on the bed, and later the gestures of the old painter as he throws out his guests and then sits to admire his painting, shifting his chair and folding his arms, have an elegance and emphasis in slow motion that they would not otherwise have. He writes:

If dancing were basket-weaving, there would be no problem about its being relegated to the role of subject matter in a cinematic or televised message. The main difficulty arises, I believe, because dance too is an art of the moving image. It does not relate to film as, for example, scene painting relates to theatre. It is, in effect, a competing medium.

The important thing here is the realization that the art of the moving image did not commence with Fred Ott sneezing for Thomas Edison with the help of a jar of red pepper, any more than it commenced with Loie Fuller doing her famous Bat Dance in somebody’s back yard for an anonymous cameraman. Both were practitioners of an art as old as humanity, if not older.10

We are at the crux of Peterson’s genius: his ability to formulate a new perspective and to test its implications.

Film has the problem of divesting itself of much that it had accomplished; of, in effect, starting over from scratch, returning to a time when it still had choices in the directions it might take, when it had not yet discovered its potentiality as a narrative or dramatic medium.

The stupendous past and a Pisgah future are clearly in the hands of experimentalists, who have nothing to lose by their pains. The traditions of the art of the moving image are as broad as they are long.11

The example he uses to illustrate his new conceptual orientation for film as an aspect of “the art of the moving image” is Maya Deren’s Choreography for Camera:

Beatty’s celebrated leap had its origins, not in film, but in the so-called Dumb Ballet of the English stage, of which Fun in a Bakehouse and Ki Ko Kookeeree were examples. The Oxford Companion to the Theatre calls the leap “the supreme test of the trick player” throughout all that part of the nineteenth century when it flourished. In this sense, Miss Deren (whose leap Beatty’s really was) with her leap joined Méliès and a company that included—not Taglioni, Grisi, or Cerrito—but Grimaldi, the Lupinos, the Conquests, and those extraordinary “entortillationists” and “zampillerostationists,” the Hanlon-Lees.12

In the first three films from Workshop 20 the students participated as actors and observers. In the summer semester of 1949, Peterson decided to let them participate in the conception of the film. A couple from Virginia (the Johnstons, as Peterson recalls) suggested that they film a traditional ballad. Mr. Johnston had just been studying the relationship of old English ballads to their American counterparts. Another student volunteered a diving suit, and still another her hamsters. The sheer incongruity of the materials must have awakened the best of the film-maker’s problem-solving and synthetic instincts. An instinct for the synthetic is normally the gift of a film editor, who is often faced with the task of making a coherent whole out of disparate and insufficient materials; Peterson, however, carried the editing principle into the very conception of his films.

The anthropological principle of Johnston’s thesis, that the ballads take on irrational and disjunctive aspects after translocation and the passage of time, became the deliberate aesthetic of Peterson’s new film; he would accelerate the disintegration by scrambling two ballads and by employing the type of cinematic ellipsis and association he had developed in his previous film.

The titles of the film mention “The Three Edwards and a Raven,” a reference to the mixture within the film of the ballads, “The Three Ravens,” and “Edward.” Parker Tyler’s notes on the Cinema 16 screening of the film in 1950 are particularly fine:

Peterson came upon two old ballads, “Edward” and “The Three Ravens,” the first a Colonial popularization of the Cain-and-Abel legend, and the second concerning three birds that witnessed a fallow-deer carry off a dying knight from the field of battle. In Peterson’s film, the mother’s passionate hysteria when she learns of “Abel’s” murder indicates that at least a symbolic incest is present, a point given more weight when we consider that “Edward” is a variation of an older Scotch ballad, “Lord Randall,” about a son who confesses to his mother that he killed his father.

In that timeless time in which the true creator does preliminary work—perhaps in a twinkle—Peterson visualized Edward, the murderous “Cain,” in kilts and the corpse of “Abel” in a diving suit; thus the two ballads are fused because the diving suit substitutes for the knight’s armor in “The Three Ravens.” Then he must have felt the violence of a complex insight: a diver’s lead shoes keep him on the seabottom, which seems equivalent to that abysmal level of instinct where anything is possible.

When the frantic mother digs up her son from the sand on the shore, she is performing again the labor she had on giving birth to him; the suit itself becomes a sort of coffin. Once more, before he is consigned to the grave, she must hold him close to her. If we can assume all this, as I believe we can, we may go further to note that the tragic emotion is ingeniously modified by two devices: one is the hopscotch game seen parallel with the main action. Every mother of two sons has the problem of balancing her affections, which must be divided between them. This moral action was once anticipated in the physical terms of the hopscotch which she played as a girl: the player must straddle a line between two squares without falling or going outside them. The second device, the boogie-woogie accompaniment with its clamorous chorus, like the first, may have been instinctively rather than consciously calculated by Peterson. It operates unmistakably: the voices and music supply a savage rhythm for the ecstatic if accursed performers of the domestic catastrophe. It is the lyrical interpretation of the tragedy and suggests the historical fact that Greek tragedy derived from the Dionysian revel. Lastly we have the sinister implement and symbol of the castration rite, the knife and the bread—perhaps representing the murderer’s afterthought rather than part of his deed.13

The Lead Shoes opens with the hopscotch game. In a film of approximately one hundred shots, this image occurs fifteen times. Its repetition contributes to the frenetic pulse of the work; like the dancing on the mattress in the earlier film, it sets the tone and rhythm of the whole; in this case, fast, jumpy, hysterical movement, often filmed backward.

The complexities begin with the next scene (introduced by another hopscotch image). The mother pulls off the diver’s helmet. Then she opens the helmet window and takes out what appear to be three rats. While she is doing this, a barefoot man in a kilt enters the frame; blood drips on his feet. Thus is the condensed and elliptical introduction of Edward. We see the helmet become bloody; then we see his bloody hands on his mother’s nightgown, and he leaves.

The penultimate repetition of the hopscotch game (the final occurrence is the last image of the film) introduces the longest and most intricate episode of the film. With the help of strangers whom she had accosted on the street, the mother manages to hoist the diver in his suit up to her balcony and drags him across the floor and onto the bed. She strips him of his suit; and then, in the film’s most enigmatic image, lowers the body rather than the suit into the street. The instant the dead man’s head hits the sidewalk, Peterson cuts to a bounding loaf of bread, suggesting a ghoulish transubstantiation. Edward picks up the bread. In a series of jump-cuts we see him eating it in an outdoor cafe. In his hands, the loaf becomes a bone. He puts it down; suddenly there is a dog in his chair munching on the bone. These shots occur one after the other without any intercutting.

Here is the point of maximum hysteria on the soundtrack. Peterson put together a jazz band, made up of the faculty of the art school where he taught. His students sing, howl, and chant, with the repetitiousness of a broken phonograph, phrases from the two ballads. He credits the Johnstons, with their experience of ejaculatory singing, for some of the intensity of the soundtrack.

The mother, at the height of her hysteria, accented by a twisting of the anamorphic lens, begins to writhe sexually on top of the empty, prone diving suit. We return to the dog at the table. In a reverse sequence, without actually reversing the photography, the bone becomes bread again, and Edward breaks it. Blood drips onto his plate, and he eats with fiendish relish as the scene fades out and then in on the last shot of the hopscotch game.

In addition to the transference that Tyler notes of diving suit to coffin to knight’s armor, Peterson has short-circuited the ballads so that the scavenging mother assumes the role of the fallow deer in “The Three Ravens” who carries off the body of the dead knight; Edward becomes the ravaging ravens, a symbolic cannibal. One of his responses, in the ballad and on the soundtrack, to the endlessly repeated question, “How came that blood on the point of your sword, my son?” was that it was the blood of his dog. Here the dog also crosses over his role to become one of the ravens, eating the bone from the bread.14

The Lead Shoes and Mr. Frenhofer and the Minotaur are spherical forms with a narrative drift. The narration, such as it is, suggests eternally fixed cycles of behavior; it is aligned with ritual and myth. In both films the vital clues to the visual action are buried in the soundtrack, which also has functions altogether separate from conveying information. The soundtracks dislocate the sequence of events, and through their anticipations of what is to be seen, they magnify the sense of the eternal and the cyclic. These two films are complementary in another way, using the Apollonian myth of Pygmalion and the Dionysian myth of Pentheus in disguised forms.

One can see in the careers of Peterson and Maya Deren, after their initial bursts of film-making, similar problems for the visionary film-maker. Maya Deren tried to establish a foundation to support the avant-garde film-maker. That work spilled over into an effort to promote the cause of independent film-making and encourage—or sometimes discourage—new film-makers. It was an effort she did not live to see fulfilled. Peterson attempted to channel his radicalism in more conventional directions—the documentary, television, the animated cartoon—and encountered all the well-known problems. With a naive oversimplification that is unusual for him, he has said, “I was trying to solve all those problems, which have subsequently been solved by a movement.”

Speaking of James Broughton, Peterson has defined the difference between their sensibilities and their works as that between visual orientation and mise en scène. Broughton wrote a brief autobiographical sketch in which he says, “Sidney Peterson introduced me to the magic of experimental film.” They are both unusually generous for one-time collaborators when referring to each other’s work.

In an essay for Film Culture 29, reprinted in the Film Culture Reader, “A Note on Comedy in the Experimental Film,” written thirteen years after The Lead Shoes, Peterson explores the comic roots of the entire avant-garde film movement; what he says scarcely applies to most of the avant-garde film activity between The Lead Shoes and the time of writing; naturally, he is referring to himself more than to anyone else. His reflections on the comic lead him to postulate a dynamiteur who must start the laughter when there is an ambivalence between the serious and the ridiculous; then he distinguishes between the audience who sees a finished film and the audience of its makers seeing the rushes and rough cuts. The feeling for participation, the sense of the making, the work behind the scenes, reveals his experimentalism in the late forties and early fifties; there is no film-maker for whom that term is more fitting than Peterson. Married to his idea of both experimentation and modernism is the notion of blague. He has pointed out the importance of Edmond and Jules de Goncourt’s Manette Salomon, a novel about pre-Impressionist studio painting in France, as a central text of the sensibility of modern art, with its distinction between work for friends and for oneself, work to be seen in the studio and work destined for the salons. Out of this distinction emerges a rhetoric of authenticity, an attention to the working process, and a new sequence of myths of the artist.

The myth of the visual sensibility prevails now. Since the Second World War a synthesis has bound the “visual” and the “dynamic” in a supposed opposition to the “literary.” Peterson’s position toward film-making, like that of Maya Deren, draws energy from that emergent synthesis, although to subsequent “dynamic visualists” in the dialectic of abstraction their works will look “literary.” Roughly stated, that position holds that the filmmaker should be his own cameraman and editor. The visualist approach implies the synthetic unity of functions which the film industry has jealously separated. A corollary to the same proposition often demands that the filmmaker appropriate the whole visual field, leading ultimately to an expressionistic employment of anamorphosis, superimposition, painting on film, and numerous other ramifications of the images as they come out of the camera “factory perfect.” The emergence of this aesthetic during the reign of Abstract Expressionism is not a coincidence.

Peterson’s distinction between visual organization and mise-en-scène boils down to a twin observation about Broughton: that he has a pronounced feeling for the dramatic and that he does not usually operate his own camera. He makes the kind of film where it is possible to employ a cameraman. The theatrical component in Broughton’s cinema actually owes its greatest debts to the popular stage of the turn of the century, especially to tableaux vivants, mimes, and variety shows. This was a theater which was brought over into the first films. A nostalgia for the origins of cinema vitalizes much of Broughton’s film-making.

If Peterson and Deren purified cinema and used its perspectives to imitate the human mind, Broughton took cinema back to the time before the elaborate narratives of the early century in order to recapture the excitement of seeing and showing human bodies in action, apparitions, and sudden disappearances, and to imbue that cinema of action with a more profound sense of the cyclical rhythms of life and the feeling for the essential he equates with poetry. In “What Magic in the Lanterns?” he wrote:

Modern poetry has been deeply influenced by film. Modern film has not sufficiently returned the compliment. … Let us be quite clear. To ask for poetry in cinema does not mean that one is asking for verse plays transferred dutifully to celluloid. … No, one is asking rather for the heart of the matter. For the essence of experience, and the sense of the whole of it. For the effort and the absurdity, the song and the touch. For how we really feel and dream—grasped and visualized afresh.

Memorable poetry has always been a dramatic ritual. The coliseum. The cathedral. The theatre. The bullring. For us, the cinema. …