KENNETH ANGER WAS born in southern California in 1930. According to his interviews, he played the role of the child prince in Max Reinhardt’s movie of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and had Shirley Temple for a dancing partner at cotillions of the Maurice Kossloff Dancing School. For him more than for any other avant-garde film-maker Hollywood is both his matrix and the adversary. In his excellent article on Anger’s films,1 Tony Rayns cites the Olympian analogy from Anger’s Hollywood-Babylon:” There was Venus and Adonis only called Clara and Rudy; there was Pan called Charlie; there was even old Bacchus named Fatty and maimed Vulcan named Lon. It was an illusion, a tease, a fraud; it was almost as much fun as the ‘old-time religion’—without blood on the altars. But the blood would come.” The ambivalent mixture of satire and homage with which that book is written amounts to an exercise in fascination characteristic of everything to which Anger devotes himself. Scandal, evil, violence, and Fascism, like Hollywood, are centers of fascination for Anger, and his films are the fields in which the dialectic of that fascination is played and fought.

Of Anger’s very early films there are no descriptions in print. Lewis Jacobs, in his contribution to Experiment in the Film, is our sole source of information about Escape Episode:

Less concerned with cinematic form and more with human conflict are the pictures of Kenneth Anger. Escape Episode (1946) begins with a boy and girl parting at the edge of the sea. As the girl walks away she is watched by a woman from a plaster castle. The castle turns out to be a spiritualists’ temple, the woman a medium and the girl’s aunt. Both dominate and twist the girl’s life until she is in despair. Finally in a gesture of defiance the girl invites the boy to the castle to sleep with her. The aunt informed by spirits becomes enraged and threatens divine retribution. The girl is frustrated, becomes bitter and resolves to escape.

The quality of the film is unique and shows an extreme sensitivity to personal relationships. But because the thoughts, feelings and ideas of the film-maker are superior to his command of the medium, the effect is often fumbling and incomplete, with parts superior to the whole. 2

Anger’s notes on his films are often the best guide to their mysteries; in every case they are interesting. In Film Culture 31, he provided the following filmography of his work before Fireworks:

WHO HAS BEEN ROCKING MY DREAMBOAT (1941)

7 min. 16mm B&W. Silent. Filmed in Santa Monica, California. Credits: Conceived, Directed, Photographed and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Cast: A dozen contemporaries recruited from the neighborhood. Synopsis: A montage of American children at play, drifting and dreaming, in the last summer before Pearl Harbor. Flash cuts of newsreel holocaust dart across their reverie. Fog invades the playground; the children dropping in mock death to make a misty landscape of dreamers.

TINSEL TREE (1941-42)

3 min. 16mm B&W. Hand-tinted. Silent. Filmed in Santa Monica. Credits: Conceived, Directed, Photographed and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Cast: A Christmas Tree. Synopsis: The ritual dressing and destruction of the Christmas Tree. Close-ups as the branches are laden with baubles, draped with garlands, tossed with tinsel. Cut to the stripped discarded tree as it bursts into brief furious flame (hand-tinted gold-scarlet) to leave a charred skeleton.

PRISONER OF MARS (1942)

11 min. 16mm B&W. Silent. Filmed in Santa Monica. Credits: Conceived, Directed, Photographed and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Camera Assistant: Charles Vreeland. Settings, Miniatures, and Costume Designed and Executed by Kenneth Anger. Cast: Kenneth Anger (The Boy-Elect from Earth). Synopsis: Science-Fiction rendering of the Minotaur myth. A “chosen” adolescent of the future is rocketed to Mars where he awakens in a labyrinth littered with the bones of his predecessors. Formal use of “serial chapter” aesthetic: begins and ends in a predicament.

THE NEST (1943)

20 min. 16mm B&W. Silent. Filmed in Santa Monica, Westwood and Beverly Hills. Credits: Conceived, Directed, Photographed and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Cast: Bob Jones (Brother); Jo Whittaker (Sister); Dare Harris—later known as John Derek in Hollywood—(Boy Friend). Synopsis: A brother and sister relate to mirrors and each other until a third party breaks the balance; seducing both into violence. Ablutions and the acts of dressing and making-up observed as magic rite. The binding spell of the sister-sorceress is banished by the brother who walks out.

ESCAPE EPISODE (1944)

35 min. 16mm B&W. Silent. Filmed in Santa Monica and Hollywood. Credits: Conceived, Directed, Photographed and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Cast: Marilyn Granas (The Girl); Bob Jones (The Boy); Nora Watson (The Guardian). Synopsis: Free rendering of the Andromeda myth. A crumbling, stucco-gothic sea-side monstrosity, serving as a Spiritualist Church. Imprisoned within, a girl at the mercy of a religious fanatic “dragon” awaits her deliverance by a beach-boy Perseus. Ultimately it is her own defiance which snaps the chain.

DRASTIC DEMISE (1945)

5 min. B&W. Silent. Filmed in Hollywood on V-J Day. Credits: Photographed and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Cast: Anonymous street crowds. Synopsis: A free-wheeling hand-held cameraplunge into the hallucinatory reality of a hysterical Hollywood Boulevard crowd celebrating War’s End. A mushrooming cloud makes a final commentary.

ESCAPE EPISODE (SOUND VERSION) (1946)

27 min. Music by Scriabin.

This shorter edition makes non-realistic use of bird wind and surf sounds, as well as Scriabin’s “Poem of Ecstasy” to heighten mood.3

The corpus of Anger’s work I have selected begins with Fireworks. His note on it is cryptic; it assumes the viewer already knows the film!

FIREWORKS (1947)

15 min. 16mm B&W. Sound (Music by Respighi). Filmed in Hollywood. Credits: Conceived, Directed, Photographed and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Camera Assistant: Chester Kessler. Cast: Kenneth Anger (The Dreamer); Bill Seltzer (Bare-Chested Sailor); Gordon Gray (Body-Bearing Sailor); crowd of sailors. Synopsis: A dissatisfied dreamer awakes, goes out in the night seeking ‘a light’ and is drawn through the needle’s eye. A dream of a dream, he returns to a bed less empty than before.4

As we watch the film we hear Anger speaking a prologue: “In Fireworks I released all the explosive pyrotechnics of a dream. Inflammable desires dampened by day under the cold water of consciousness are ignited that night by the libertarian matches of sleep, and burst forth in showers of shimmering incandescence. These imaginary displays provide a temporary relief.”

The opening image is of water; a burning torch is dipped into it. Then there is a close-up of a sailor. As the camera dollies back from his face we see in flashes of illumination, like lightning, that he is holding the protagonist, the dreamer, in his arms. After a fade-out, the camera observes the same dreamer in bed. Another dolly movement shows he is alone. He stirs, wakes. A pan of the room reveals a marble or plaster hand with a broken finger. Images of the dreamer’s hands moving on his own body suggest masturbation. We see in a long shot of the whole room that he has a monstrous erection under the covers. Then he takes out an African statue which breaks the phallic illusion. Photographs are scattered on the floor of the earlier shot of the sailor holding him. From these photographs it is clear that he is bruised and bloody.

Once he is out of bed, the camera pans up the dreamer’s pants; he zips his fly just as the camera eye passes by; then to his face, framing a composition with the broken hand in the background. The camera follows him fluidly as he picks up the photos, throws them into the cold fireplace, and puts on his shirt. Another composition-in-depth frames the dreamer between the primitive phallic statue in the foreground and mirror in the far back as he takes out U.S. Navy matches. He leaves his room through a door marked GENTS in grotesquely large print.

The scene shifts as he passes through the door from compositions-indepth, with regular camera movements, to fixed shots of the protagonist highlighted in black, formless space. A muscle-bound sailor appears before the painted backdrop of a bar. The dreamer approaches him and watches as he flexes his bare arm and chest muscles in close-ups. When the dreamer asks him for a light, the sailor punches him, knocks him off the screen, then twists his arm behind him. Suddenly, they are before the fireplace in the original room. The sailor takes a torch of sticks out of the fire and lights the cigarette for the dreamer. Then he picks up his cap and leaves.

Again the scene shifts to the dreamer highlighted against black. From above, the camera looks down on the hero, smoking. He turns abruptly and, in the next shot, sees a gang of sailors. They come at him, passing from light through darkness into light again. The camera follows their shadows. They rush him, carrying chains.

The following scene of orgasmic violence is constructed out of closeups of the dreamer’s body isolated in darkness and shots of the sailors performing violent acts just off screen. From above we see fingers shoved into the dreamer’s nostrils, and blood shoots out of his nose and mouth. A sailor twists his arm, and he screams hysterically. A bottle of cream is smashed on the floor. With a broken piece a cut is made in his chest; hands separate the pudding-like flesh to reveal a heart like a gas meter. His chin is framed in the bottom of the black screen like a frozen wave. Cream poured from above flows over it into his mouth. Cream washes his bloody face; then it flows down his chest. There is a pan of empty urinals. The GENTS door opens, but no one is behind it. Then the sailor of the opening sequence appears; the camera dollies to his face in the reverse of its initial movement. In the next shot, he opens his fly and lights a roman candle phallus which shoots out burning sparks.

The fire of the roman candle becomes the flame of a wax candle on the tip of a Christmas tree which the dreamer wears like a giant hieratic helmet. He bows toward the camera, enters his room, and lights the photographs in the fireplace with the burning tree. We see him sleeping again, as in the opening. But now there is a fire in the fireplace; and a pan of the bed shows someone in it beside him. Scratches over the filmed images hide his face from us. The pan continues to the plaster hand, now repaired so that all its fingers are whole. The hand falls into the water, where the torch had been quenched in the first shot. “The End” appears in superimposition over the water.

Fireworks is a pure example of the psycho-dramatic trance film: the film-maker himself plays out a drama of psychological revelation; it is cast in the form of a dream beginning and ending with images of its hero as a sleeper; finally, the protagonist is the passive victim of the action of the film. Actually, there are two dreams in Fireworks. The first is the brief disjointed opening couplet of fiery images—the extinguishing of the torch in water and the dolly shot of the sailor holding the beaten dreamer amid flashes of lightning and peals of thunder. A slow fade-out, the only one in the film, marks the end of this sequence, which we can presume to be a dream, because the subsequent image is of a sleeper; this is further confirmed a minute later when we see the pictures of the sailor and the dreamer scattered beside the bed, as if they were the objects of a masturbation fantasy before sleeping.

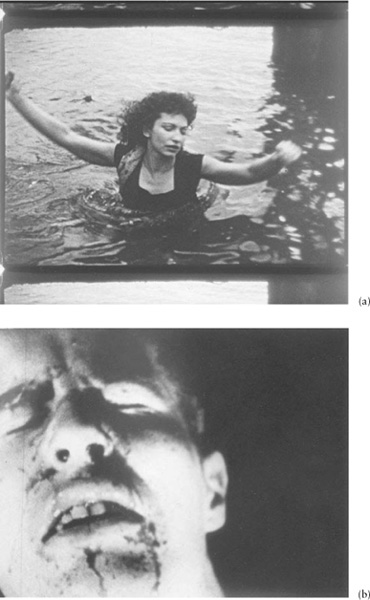

The psychodramatic trance film: (a) Maya Deren in Ritual in Transfigured Time; (b) Kenneth Anger in Fireworks; (c) Stan Brakhage reflected in the metal of a toaster in Flesh of Morning; (d) Walter Newcomb in negative in Stan Brakhage’s The Way to Shadow Garden.

The day and night of the falsely wakened dreamer betray a dream structure before the final confirmation that the whole film has been a dream in the last images of the sleeper. The exaggerated GENTS sign; the substitution of a gas meter for a heart; the repeated sudden changes of locale from barroom to fireside, from men’s room back to bedroom are standard in the cinematic vocabulary of the dream. Finally, the dramatic substitution of a roman candle for a penis, from which the film derives its title, suggests that we have entered the mind of the sleeper rather than that the sleeper has awakened to the causal world.

Significantly, a photograph occupies a central and paradoxical position within the film as both the source and residue of the dream. If the opening passage of the protagonist held by the sailor, followed by the same protagonist waking, suggests that the former was his dream, the photograph by the side of his bed, showing the same image as the dream, appears to be the source of his nocturnal masturbation fantasy which had become “animated” in his sleep. Yet as the waking day proceeds, its mimesis veers towards ironic displacements: for a match, a bunch of burning sticks is substituted; for a heart, a metallic meter; for a penis, a roman candle; for semen, cream. What terminates the dream and allows us to see the sleeping figure unmediated by his own imagination is the burning of the very photograph that seemed to be the source of the dream. Here the space and time of the dream coincide with the duration of the photograph as a fetishistic object occupying the twilight area between an experience of dubious authenticity and the full awakening that is continually postponed.

The filmic dream constituted for Anger, as it had for Deren, a version of the perceptual model that generated most of the subjective films of the American avant-garde in the 1940s. Whenever that model is operating, a subject-object polarity is established in which the camera’s relationship to the field of its view reflects the functions of a receptive mind to the objects of its perception. The metaphor of the dream permits the reflexive gesture of duplicating the presence of the film-maker (subject) or his mediator in front as well as behind the camera. The introduction of photographs or other iconic representations as objects of the camera’s gaze merely adds another reflexive turn to the model without altering it. Thus Mother’s Day postulates an organizing consciousness enmeshed in some variant of nostalgia. Likewise the anamorphosis of Peterson’s films pointed to a radically askew perspective grounded in a fictional being within whom the psychological and intellectual tensions of each film converged.

There is a comic or satiric element in the hyperbolic symbolism of Fireworks, as in almost everything Anger makes. The roots of Anger’s aesthetic lie in French Romantic decadence of the late nineteenth century. Like his predecessors, he favors an art which argues with itself. For him it is not a matter of vacillation. Anger makes his films with an intense involvement in his subject and often an equally intense criticism of their limitations. The simultaneity of the prophetic and the satiric distinguishes the greatest Romantic art, and the failure of the classically oriented taste and criticism of our times has been not to credit the Romantics with a sense of humor and to ridicule their achievements with the same ridicule they practiced on themselves. The crucial difference, of course, is that Romantic satire measures the limitations of its heroes in their quest for absolute freedom, while classical taste calls even the limited movement toward those ends grotesque.

In Fireworks, poetic irony plays considerably less of a part than in all of Anger’s later films. In Scorpio Rising it reaches its climax, as I shall show. Fireworks may be the strongest of the trance films. It is truly remarkable that a seventeen-year-old film-maker could make so intense an analysis of himself at a time when any allusion to homosexuality was taboo in the American cinema. But it is all the more remarkable that he invested his film with the critical humor of the false erection, the gas meter heart, the firecracker penis, and the Christmas tree miter. In 1947 Anger had not yet developed his feeling for the opposition of contraries or for total ambivalence as a structural principle in cinema. But the ironic sensibility had begun to manifest itself.

Later Anger wrote, “This flick is all I have to say about being seventeen, the United States Navy, American Christmas, and the Fourth of July.”

Before we go on to consider his later films, I would like to call attention to certain textural properties of Fireworks. The opposition between scenes in depth, with prominent foreground and background objects, and scenes of figures isolated in blackness has been indicated in my synopsis. There is a considerable amount of camera movement early in the film. Each movement is very steady and is punctuated so as to distinguish two visual facts. The opening dolly shot shows first the sailor, then reveals that he is holding a bloody body in his arms. The dolly across the bed shows first that the dreamer is asleep, then that he is alone. The pan up his pants as he is getting dressed shows him zipping up his fly, then fixes his torso in relation to the broken hand in the background. The dolly at the end of the film has three phases; first the dreamer is back in bed; then there is someone beside him; and finally the broken hand is repaired.

It was a long time before he finished and released his next film, Eaux D’Artifice (1953). Its title might be translated “Water Works” (“Fireworks” would be “Feux d’Artifice” in French), suggesting the dialectical relation it has to the earlier film. Here we see the first mature development of the ironic sensibility and the balancing of contraries as a formal endeavor. One must not forget that although these two films are six years apart, Anger thinks of his films as a whole rather than as totally independent works. He is constantly revising them, subtly altering their relationships to one another. For the special program of his complete works at the Spring Equinox of 1966, he hand-tinted the candle atop the Christmas tree in Fireworks and the scratched-out face of the man in bed beside the dreamer to underline the relationship with Eaux d’Artifice, which ends soon after the appearance of a hand-tinted fan.

In Eaux D’Artifice we see a baroque maze of staircases, fountains, gargoyles, and balustrades. A figure in eighteenth-century costume, flowing dress, and high headpiece hurries through this environment while the camera zooms into and away from the mask-like faces of water spirits carved in stone or studies in slow motion the fall of fountains and sprays. Just before the end of the film, the heroine flashes a fan, then turns into a fountain, and her silhouetted form dissolves into an identical fountain arrangement.

The entire film has a deep blue color, achieved in the printing through the use of a filter. The sole exception is the brief flashing of the fan which the film-maker tinted green by hand. The whole film is successfully tuned to a fugue by Vivaldi. Unlike Fireworks, its interest is not narrative, but primarily rhythmic, and its elements are the pace of the heroine, the speed of the zooms, the slowness of the retarded waterfalls, and above all, the montage in relation to the music.

In his early notes for the Cinema 16 catalogue, Anger describes this film as “the evocation of a Firbank heroine,” and her flight as “the pursuit of the night moth.” His new note is:

EAUX D’ARTIFICE: SUMMER SOLSTICE 1953

“Pour water on thyself: thus shalt thou be a Fountain to the universe. Find thou thyself in every Star! Achieve thou every possibility!” Khaled Khan, The Heart of the Master, Theorem V. Hide and seek in a nighttime labyrinth of levels, cascades, balustrades, grottoes, and ever-gushing, leaping fountains, until the Water Witch and the Fountain become One. Dedicated to Pavel Tchelitchew. Credits: Conceived, Directed, Photographed, and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Cast: Carmillo Salvatorelli (The Water Witch). Music: Vivaldi. Filmed in the gardens of the Villa D’Este, Tivoli, by special permission of the Italian Department of Antiquities, on Ferrania Infra-Red. Printed on Ektachrome through a Cyan filter. The Fan of Exorcism hand tinted by Kenneth Anger with Spectra Color.5

An earlier version of this note adds that Thad Lovett was the camera assistant and that the heroine’s costume was designed by Anger.

Anger has said that he chose Carmillo Salvatorelli, a midget, for the part in order to create a play of scale. The allusion to Firbank in the earlier note can be traced to the end of Ronald Firbank’s novel, Valmouth, where Niki-Esther, at the time of her marriage, went into the garden in pursuit of a butterfly, dressed in her wedding gown and carrying her bouquet.

According to Tony Rayns:

Anger’s grandmother was a costume mistress in silent films, and it was she who, working with Reinhardt, got Kenneth into the 1935 Midsummer Night’s Dream. In his early youth Anger used to love dressing up in her costumes (“my transvestite period”) and it was this that inspired the costume in Eaux d’Artifice, worn there by a circus dwarf Anger met in Italy. The Lady (“a Firbank heroine in pursuit of a nightmoth”) owes her plumes to Anger’s Reinhardt costume, and her light-headedness to her past in Anger’s childhood.6

Eaux D’Artifice plays the same role in the evolution of Anger’s style that Choreography for Camera played in Deren’s. Both films are what I have labeled the single-image film, and both culminate in a union between protagonist and landscape. That Deren and Anger, as well as Curtis Harrington and Stan Brakhage in their generation of film-makers, should follow the same course of formal invention is not an indication that one copied the other; it shows, however, the options open to serious, independent film-makers. Furthermore, the achievement of one artist in a given form—say the trance film—did not exhaust that form for the others. Many of the film-makers of that generation went in similar directions in their work at different times. The sequence of forms discovered by Maya Deren in her six films between 1943 and 1958 started a pattern that extended from the late 1940s through the 1960s. To this parallel evolution of different film-makers I shall return repeatedly in this book.

Between the completion of Fireworks and of Eaux D’Artifice Anger had initiated many projects. In 1948 he attempted to make a feature-length color film about faded Hollywood stars and their fantasy mansions. Soon after that the footage for The Love That Whirls, with simulated Mexican rituals in the nude, was destroyed by the laboratory to which it was sent for processing because they deemed it obscene.

He moved to Paris in 1950, where he stayed on and off for the whole of that decade. There he began to shoot a 35mm black and white film called La Lune des Lapins, which he called “a lunar dream utilizing the classic pantomime figure of Pierrot in an encounter with a prankish, enchanted Magic Lantern,” but he ran out of money. The next year, 1951, he filmed in 16mm a version of Cocteau’s ballet, Le Jeune Homme et La Mort, in the hope of raising money to make a 35mm film of the whole ballet. That financial endeavor also failed.

For two years after that he prepared to film Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror, again incorporating professional dancers from the Marquis de Cuevas’s and Roland Petit’s companies. He got no further in the production than rehearsals and tests. It was following the collapse of Maldoror that he made Eaux D’Artifice. A year later, in 1954, he returned to California to settle a family inheritance and made Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome with the money.

There have been at least four versions of Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome at different times. The first, which no one to my knowledge has seen, was edited to a soundtrack by Harry Partch, the American composer and inventor of several exotic instruments. The version that was in distribution in the late 1950s and up to 1966 had Janaček’s Glagolithic Mass for a soundtrack. For the second Experimental Film Competition, held during the Brussels World’s Fair of 1958, he made a version with three screen synchronous projection for the climactic final two-thirds of its forty minutes. In 1966 he issued his Sacred Mushroom version of the film, subtitled “Lord Shiva’s Dream,” at the occasion of his Spring Equinox program at the Film-Makers’ Cinemathèque in New York. This version began with a reading of the whole of Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, from which Anger derived the original title of the film, while still pictures of Aleister Crowley and images from the repertory of occult symbols and talismans appeared on the screen. To the first part of the film Anger had added some more photographs of Crowley in superimposition and images of the moon at strategic points. It was in the final third of the film, where once the images on two flanking screens had appeared, that he made his major changes. Superimposition, sometimes many layers deep, replaced the earlier linear development and montage. To the multiplication of his characters he added shots from Harry Lachman’s Dante’s Inferno, mainly crowd scenes of burning, printed in red, and most of Puce Moment, a fragment of the unmade Puce Women, which Anger had completed in 1949, distributed until 1963, and then withdrew from the public. He also mixed sounds of screaming with the music of Janaček, which he otherwise retained entirely.

The opening sequence of Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome is one of Anger’s finest cinematic achievements. A slow pan up the title card, with gold letters and lines against black, blends into a slow pan up over the edge of a bed, suggesting the breaking of dawn. The camera passes a constellation of glittering crystalline objects too close to be in focus. As the pan continues to ascend we perceive that it is a string of jewels we have been looking at. Now they are being slowly raised and wrapped around the hands of a yet unseen figure on the bed.

A slow dissolve brings us closer to the hands, and the camera pans past them to the right to reveal a table with a pipe and several rings. This sequence continues for several minutes; most of the separate shots are joined by dissolves which underline the slow and hieratic quality of the gestures of the waking figure who, Anger tells us, is called Lord Shiva. He swallows the string of jewels, rises from the bed before an elaborate dragon mirror, passes through several doors and then beyond a Japanese curtain to perform his ritual cleansing before a three-sided mirror. It is here, as he leans forward to the mirror, that we see his first transformation: his face fades out, and we see a man-like beast with long fingernails filmed in red light. From Anger’s notes, we know this is the hero’s metamorphosis as Beast 666 of the Apocalypse, or simply the Great Beast.

The lavish color of the rooms; their exquisite ornamentation; the slow movements of the camera and of Shiva; his sensual handling of objects; and the slightly elliptical sequence of dissolves which both cuts short each action and blends it into the next combine with the opening of Janaček’s Mass to create a sequence of excessive richness and to set an intense expectation for the film.

Another upward pan, somewhat faster than the opening shot, reveals a woman in brilliant white clothes and make-up with flaming red hair isolated in blackness. She is Kali and the Scarlet Woman, according to Anger’s notes. She turns her head to the right, then to the left, looking offscreen. In Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome the offscreen glance has the crucial function of relating the positions of the film’s numerous characters to the central figures of Shiva and Kali. To a great extent the revisions of the Sacred Mushroom version have obscured this principle in the final third of the film, where superimposition has assumed the structural burden formerly based upon the geometry of offscreen looks and movements.

With the turn of her head the Scarlet Woman sees Shiva at his door. She turns again, and he has become the Great Beast. In a series of dissolves she discloses a tiny statue of a devil in her hands and offers it to him. In his hands it turns to fire. With that fire the Great Beast lights her cigarette, or “joint,” for her. As she puffs it, we see a superimposed photograph in blue tint of Aleister Crowley smoking a pipe.

In the opening passage of the film, Anger used drapery, painted walls, and rich costumes as the instruments of color control and color rhythm. In the following scenes, in which Shiva in his several guises receives the gifts of the gods, Anger gets his essential color alterations from filtered lights with which he spotlights his figures in black space. This recalls the two kinds of lighting and evocation of space in Fireworks and the color control of Eaux D’Artifice achieved through filtering (in that case, in the printing of the film, not in the lighting of the scene as in Inauguration).

At this point in analyzing the film it would be useful to quote Anger’s notes:

INAUGURATION OF THE PIEASURE DOME

Sacred Mushroom Edition Spring Equinox 1966 otherwise known as ‘Lord Shiva’s Dream’

“A Eucharist of some sort should most assuredly be consumed daily by every magician, and he should regard it as the main sustenance of his magical life. It is of more importance than any other magical ceremony, because it is a complete circle. The whole of the force expended is completely re-absorbed; yet the virtue is that vast gain represented by the abyss between Man and God.

“The magician becomes filled with God, fed upon God, intoxicated with God. Little by little his body will become purified by the internal lustration of God; day by day his mortal frame, shedding its earthly elements, will become the very truth of the Temple of the Holy Ghost. Day by day matter is replaced by Spirit, the human by the divine; ultimately the change will be complete; God manifest in the flesh will be his name.”—The Master Therion (Aleister Crowley), Magick in Theory and Practice.

Lord Shiva. The Magician, wakes. A convocation of Theurgists in the guise of figures from mythology bearing gifts: The Scarlet Woman, Whore of Heaven, smokes a big fat joint; Astarte of the Moon brings the wings of snow: Pan bestows the bunch of Bacchus; Hecate offers the Sacred Mushroom, Yage. Wormwood Brew. The vintage of Hecate is poured: Pan’s cup is poisoned by Lord Shiva. The Orgia ensues; a Magick masquerade party at which Pan is the prize. Lady Kali blesses the rites of the Children of the Light as Lord Shiva invokes the Godhead with the formula, “Force and Fire.” Dedicated to the Few, and to Aleister Crowley; and to the Crowned and Conquering Child. Credits: Conceived, Directed, Photographed and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Costumes. Lighting and Make-up by Kenneth Anger. Properties and Setting courtesy Samson De Brier. Cast: Samson De Brier (Lord Shiva, Osiris, Cagliostro, Nero, The Great Beast 666); Cameron (The Scarlet Woman, Lady Kali); Kathryn Kadell (Isis); Renata Loome (Lilith); Anais Nin (Astarte); Kenneth Anger (Hecate); the late Peter Loome (Ganymede). Music: Janaccek. Filmed at Shiva’s house, Hollywood, California, and another place. Printed by Kenneth Anger in Hand Lithography System on A, B, C, D, and E rolls, on Ektachrome 7387.7

A note from the Cinema 16 New York premiere in 1956 gives a somewhat different synopsis of the same action:

The Abbey of Thelema, the evening of the “sunset” of Crowleyanity. Lord Shiva wakes. Madam Satan presents the mandragore, and a glamor is cast. A convocation of enchantresses and theurgists. The idol is fed. Aphrodite presents the apple; Isis presents the serpent. Astarte descends with the witch-ball, the Fairy Geffe takes wing. The gesture of the Juggler invokes the Tarot Cups. The Elixir of Hecate is served by the Somnambulist. Pan’s drink is venomed by Lord Shiva. The enchantment of Pan. Astarte withdraws with the glistening net of Love. The arrival of the Secret Chief. The Ceremonies of Consummation are presided over by the Great Beast-Shiva and the Scarlet Woman-Kali.8

In that cast of characters Aphrodite is played by Joan Whitney, the Somnambulist by Curtis Harrington, Renata Loome is called Sekmet (rather than Lilith), and Pan is listed as Paul Andre, although still other credits identify him as Paul Mathison, who also painted the title card.

The ambiguity of roles and synopses points out the inessential nature of the identifications. Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, like Deren’s The Very Eye of Night and Markopoulos’s The Illiac Passion, both made after it, is a mythographic film in its aspiration to visualize a plurality of gods. What is more important than the identification of characters in each of these difficult films is the way in which the film-maker sustains a vision of the divine in cinematic terms. Both Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome and The Illiac Passion, with their multiplication of divinities and their resolution through a central figure, present versions of the primary Romantic myth of the fall of a unitary Man into separate, conflicting figures, a myth that dominates the prophetic writings of Blake and finds expression in the Prometheus Unbound of Shelley.

Each of the divine figures of the film offers a gift to Shiva in one of his forms after the lighting of the Scarlet Woman’s “joint.” The subsequent sequence, which parallels the dramatic entrances of Pan and Astarte, has a more complex structure. We see for the first time at this point the preview of a kind of superimposition that Anger employs repeatedly: two images, mirror inversions of each other, seen together. Later in his employment of this kind of superimposition of the Scarlet Woman, she will be seen looking both left and right, Janus-like.

With a gradual shift of interest, the emphatic entrance of Pan becomes the equally emphatic entrance of Astarte. She lowers her mesh-stockinged feet on to a fur cushion; Shiva unwinds her blue dress; as she lifts her arms over her head in a circular motion, passing momentarily out of screen, a pearl in her hand changes first into a silver ball, and then, with another revolution, into a silver globe suggesting the moon. She gives it to Shiva. In two dissolves the globe shrinks again into a pearl, and he swallows it like a pill. Suddenly he sprouts tiny wings and smiles effeminately.

In a scenic breakdown originally in French, presumably by Anger himself, of the three-screen version of the film, the action I have so far described represents the first act (“The Talisman”) in three scenes:

scene 1 In the Abbey of Thelema, Lord Shiva wakes.

scene 2 The Goddess Kali presents the mandragore, and the enchantment begins.

scene 3 An assembly of magicians and theurgists transformed into Saints: Aphrodite, Isis, Lilith, Astarte offer their talisman, potent with the Powers of the Age of Horus: the God of Ecstasy and Violence, the God of Fire and Flame. Pan arrives bearing Hermes’ gift.

That much of the film was to be on a single screen. The following two acts, of three and two scenes respectively, were on a triptych.

What Anger called the second act (“The Banquet of Poisons”) begins as the Great Beast, with the Scarlet Woman beside him, snaps his fingers and Cesare, the Somnambulist, taken from Weine’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, appears behind his hand. The film-maker Curtis Harrington plays this role in white make-up and black tights. Like his prototype in the 1919 film, he walks stiffly with arms outstretched. The Beast points and the sleepwalker leaves the frame. The next shot, joined to the previous one by a dissolve, is one of the most impressive in the film: the Somnambulist passes a row of candles and approaches a black wall, upon which are drawn Egyptian cats. As he nears the wall a passage opens in it, and he passes into a bright and silken sanctum where his zigzag movements are only occasionally glimpsed by the camera. In one of the later versions of the film, Anger has superimposed a cartoon of Crowley’s face over the image so that the door opens not only to the sanctum but into Crowley’s head.

(a) Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome: Lord Shiva eats the jewels.

(b) The Great Beast lights the “joint” of the Scarlet Woman, with a superimposition of Aleister Crowley.

(c) The arrival of Pan.

(d) Serving the elixir.

Another dissolve brings us into the sanctum where Cesare takes an amphora from the masked figure of Hecate. He pours a powder-like substance from the amphora for the Beast and the Scarlet Woman. Shiva makes a magical gesture (Anger identified it as the Tarot of the Juggler) and two chalices rise by his sides. In this passage, the montage returns again and again to Shiva’s eyes, glancing demonically from his green-tinted face. Soon the child Ganymede makes his first appearance, pouring drinks for Shiva, Pan, and Lilith, who are gathered in a single composition with three different tints—Shiva, purple, Pan, yellow, Lilith, red. Shiva pours poison into Pan’s drink from the hidden chamber in his ring. Pan drinks and clutches his neck.

(e) Pan poisoned.

(f) A mirror image superimposition from the orgia.

(g) Lady Kali blesses the rites before the fires of Hell.

(h) Lord Shiva invokes the godhead.

At this point the linear development of the film evaporates; the multiple superimposition begins. There are no more dissolves; the pace changes from slow to frenzied. Only at strategic moments, as will be pointed out, does a single image appear on the screen without superimposition.

Astarte unfolds her net over the changing images of gods and goddesses. Suddenly we see Pan, without superimposition, possessed by the poison. There is a fade-out. We return to a triple superimposition of Astarte dancing with her net over the images of the revelers. Then a veiled figure emerges from the sanctum over the superimposition of the gold and black title card. Again the action returns to Astarte’s dance, sometimes seen from three different camera depths simultaneously. Pan is attacked and beaten with feathers. The goddesses’ feet kick and press his chest, while the first images of the hell fire of Dante’s Inferno enter the texture of the film. This is the fated sparagmos for which the orgy was convened.

Then the Scarlet Woman appears in her manifestation as Kali, seated on a throne with one breast bare. The superimposition ceases as she surveys the scene. The hell fires shoot up behind her. Sometimes her image appears over that of Shiva whose hand gestures control the orgy; other times we see three different views of her at once.

The camera dollies in on the single image of the veiled figure dancing wildly. The pace of the zooms on the masked dancer increases with the intensity of Pan’s sparagmos until, at the end of the film, Kali raises her hand in benediction, and Shiva smiles and gestures with his hands. After a montage of occult symbols, including a pentacle and the eye of Horus, the image fades out on a single shot of Shiva bringing his hands together.

Even with the introduction of superimposition, the disjunctive editing of the dances of Astarte and the masked figure and the introduction of material from two completely different films, the scenario of the Sacred Mushroom version is not so different from the outline of the three-screen projection, in which the three scenes of the second act (“The Banquet of Poisons”) are,

scene 1 The Somnambulist brings the Elixir of Hecate. Communion of the Saints: “You are Holy; whose nature is unformed; You are holy, the great and powerful Master of light and darkness.”

scene 2 The drink of Pan is poisoned by an aphrodisiacinitiatory powder that Shiva had hidden in a chamber of his ring. The intoxication of Pan.

scene 3 Astarte’s return with the net of Love.

The third act (“The Ceremonies of Consummation”) has two scenes:

scene 1 The arrival of the Secret Chief. The invocation of the Holy Fire. The Infinite Ritual.

scene 2 The ceremonies of consummation are presided over by Shiva and Kali, The Whore of Babylon and The Great Beast of the Apocalypse.

Anger told Take One magazine about the sources of this film in the work of Crowley:

The film is derived from one of Crowley’s dramatic rituals where people in the cult assume the identity of a god or a goddess. In other words, it’s the equivalent of a masquerade party—they plan this for a whole year and on All Sabbaths Eve they come as the gods and goddesses that they have identified with and the whole thing is like an improvised happening.

This is the actual thing the film is based on. In which the gods and goddesses interact and in The Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome it’s the legend of Bacchus that’s the pivotal thing and it ends with the God being torn to pieces by the Bacchantes. This is the underlying thing. But rather than using a specific ritual, which would entail quite a lot of the spoken word as ritual does, I wanted to create a feeling of being carried into a world of wonder. And the use of color and phantasy is progressive; in other words, it expands, it becomes completely subjective—like when people take communion; and one sees it through their eyes.9

In a British newspaper, Friends, he spoke of the costumes of Scorpio Rising, with a relevance to the concerns here:

Even in fancy dress films the people are still as I see them and how they see themselves. In Rio you have people who live in shanty towns and save up all year for the fab costume that they will wear for the Carnival, and that’s what they live for the whole year. For that spangled moment: and during the Carnival when they’re all dressed up, that’s really them, it’s not them when they are working, sweeping the street or doing somebody’s washing.10

In a film of the complexity of Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome one has to turn from the film-maker’s program notes to the myth of the film itself. Everything in the film, as it is now available in the Sacred Mushroom edition, must be measured in terms of the figure of the Magus. The essential tension of the film rests on the resolution of the Magus’ several aspects into a unified, redeemed man, or man made god, to use Anger’s terms. The final shot of the film is the turbanned Shiva completing the semicircular hand gesture he had been making throughout the climax of the film; the Magus’ apotheosis, the Great Beast, Nero, Cagliostro, and the winged Geffe are reunited. Not only they, but all the actors of the film are subsumed in his power and glory. If, as Anger’s remarks suggest, these characters are most themselves when assuming the personae of gods, they sacrifice their “spangled moment” to the central energy of the Magus; for Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome is not an apocalypse of liberated gods or chaotic demons, nor is it a perversion of the myth of Pentheus and Dionysus, in which the god is devoured, although Pan is as much the “eucharist” in this film as the potion of Hecate. What divinity the others obtain comes through the Magus.

For the spectator, the Sacred Mushroom version fuses the perspectives of Shiva with Pan. The opening of the film, with a solemnity and slowness of action suggestive of the traditional Japanese Noh and Kabuki theaters, dramatizes the hierophant’s point of view. Immediately after the poisoning of Pan, the style switches to the delirium of the intoxicated god, with a punctuation of shots of Kali and Shiva from the sober perspective of control. Disregarding the notes again, we see that Shiva’s most spectacular act is the transformation of the Scarlet. Woman into Kali when she reappears as the diabolic female in the superimposition sequence over the flames of hell. Ultimately, she too must be subsumed into the Magus.11

The recurrent theme of the American avant-garde film is the triumph of the imagination. Nowhere is this clearer than in the films of Anger. Here it triumphs over the superficiality of the masquerade, the campiness of the actors, and the shabbiness of Hollywood’s reconstruction of Dante’s hell. The opposition of the reality principle and the imagination, which I mentioned in discussing Fireworks, operates more covertly in this film. It is in his next completed work, Scorpio Rising, that this dialectical process reaches its maturity and becomes the organizing principle of the film.

There is nearly a decade between the two works. We do not know what formal evolution might have been shown in his version of The Story of O, which he prepared in the late fifties but never shot. In a history of ruined projects, stolen films, and works aborted due to insufficient funds, the abandonment of The Story of O, in part because one of the actors turned out to be involved in a kidnapping, reaches outrageous dimensions. In 1955 Anger managed to complete a documentary film of the erotic paintings Crowley made for his Thelema Abbey in Sicily, but that film is either lost or Anger does not want to show it. In 1960 J. J. Pauvert published his Hollywood-Babylon. In 1962 Anger returned to the United States, and while living in the Brooklyn apartment of the film-makers Willard Maas and Marie Menken, began to make Scorpio Rising.

Scorpio Rising is built around the ironic interaction of thirteen popular songs with the same number of schematic episodes in the life of a motorcycle gang. The quotation from Crowley with which Anger prefaces his note to the film refers to his use of the songs:

It may be conceded in any case that the long strings of formidable words which roar and moan through so many conjurations have a real effect in exalting the consciousness of the magician to the proper pitch—that they should do so is no more extraordinary than music of any kind should do so.

Magicians have not confined themselves to the use of the human voice. The pan-pipe with its seven stops, corresponding to the seven planets, the bull-roarer, the tom-tom, and even the violin, have all been used, as well as many others, of which the most important is the bell, though this is used not so much for actual conjuration as to mark stages in the ceremony. Of all these the tom-tom will be found the most generally useful. (The Master Therion, Magick in Theory and Practice.)

The body of the note divides the film into four parts:

A conjuration of the Presiding Princes, Angels, and Spirits of the Sphere of MARS, formed as a “high” view of the Myth of the American Motorcyclist. The Power Machine seen as tribal totem, from toy to terror. Thanatos in chrome and black leather and bursting jeans. Part I: Boys & Bolts: (masculine fascination with the Thing that Goes). Part II: Image Maker (getting high on heroes: Dean’s Rebel and Brando’s Johnny: the True View of J. C.). Part III: Walpurgis Party (J. C. wallflower at cycler’s Sabbath). Part IV: Rebel Rouser (The Gathering of the Dark Legions, with a message from Our Sponsor). Dedicated to Jack Parsons, Victor Childe, Jim Powers, James Dean, T. E. Lawrence, Hart Crane, Kurt Mann, The Society of Spartans, The Hell’s Angels, and all overgrown boys who will ever follow the whistle of Love’s brother. Credits: Conceived, Directed, Photographed, and Edited by Kenneth Anger. Cast: Bruce Byron (Scorpio); Johnny Sapienza (Taurus); Frank Carifi (Leo); John Palone (Pinstripe); Ernie Allo (The Life of the Party); Barry Rubin (Pledge); Steve Crandell (The Sissy Cyclist). Music: Songs interpreted by Ricky Nelson, Little Peggy March, The Angels, Bobby Vinton, Elvis Presley, Ray Charles, The Crystals, The Ron-Dells, Kris Jensen, Claudine Clark, Gene McDaniels, The Surfaris. Filmed in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Walden’s Pond, New York, on Ektachrome ER.12

With Scorpio Rising Anger began to refer to some of his films as “Puck Productions.” A credit with that name appears before anything else in the film. On it we see a Bottom-like ass with a banner reading, “What Fools these Mortals Be,” a reference not only to A Midsummer Night’s Dream but also to Anger’s own childhood performance in the Max Reinhardt film version. In the penultimate section of Scorpio, as the motorcycle race is in full swing, we see a brief shot of Mickey Rooney, as Reinhardt’s Puck, cut into the film as if he were cheering on the riders. In this brief instance of the injection of the image from the Hollywood film into the action of his own film, Anger establishes a series of intellectual vibrations which reach to the core of his dialectical vision. In the present case, we are struck first by the wit of the juncture; then, as we remember the antics of Shakespeare’s Puck, we realize that he is cheering them on to their deaths; and finally, we recognize the ironic loss of intensity implicit in the use of Hollywood’s, not Shakespeare’s, Puck.

The lyrics of the songs—ironic because they are “found objects” from popular culture—comment upon and qualify our thoughts about the visual images. The intensity and complexity of the ironies vary greatly from song to song; nevertheless, the end of one song and the beginning of another is a dramatic highlight at every transition, and the spectator awaits eagerly the detonating image which will fuse the next song to the next episode.

Each of the thirteen sections has a comic highlight or a dramatic surprise. Often the very first shot of a new sequence marks a visual collision with what we have been watching; often Anger holds his punch shot half a minute until the central phrase of the song’s lyrics has been uttered so that the interaction of picture and sound will be synchronous. The force with which he achieves this is concentrated in the central episodes of the film.

The first four sections of Scorpio Rising form an introduction to the film. From the very first shots—the unveiling of a motorcycle in a garage, then a series of horizontal and vertical pans of bike parts, lights, shining chrome fenders, young men oiling gears—it is clear that the texture of the film is unlike anything Anger has done before. This is a film almost without superimposition, filtered lights, or isolated figures in blackness. Anger still uses the coordination of the offscreen look, especially in collaging foreign material. The low-key lighting makes possible a lush pastel view of motorcycle cushions, lights, and portions of chrome with stars of light reflecting off them. As usual the camera movements are steady and slow, but the rhythm of the film as a whole is much quicker than anything Anger had ever made before.

The comic moment of the first scene comes at its end. Framed by quick zooms in on a plaster scorpion, the back of a cyclist rises before a red wall, and as he ascends, we can gradually read the title Scorpio Rising spelled out in silver studs on the back of his leather jacket. When he is standing erect, we see “Kenneth Anger” studded at the belt line. He turns around, revealing his bare chest and navel as the song and episode end. The subsequent segment simply prolongs a single metaphor: the montage compares motorcyclists tightening bolts to a child winding up three toy cycles and letting them roll at the camera. The song “Wind-Up Doll” underlines the comparison.

The unveiling, greasing, shining, and completing of the motorcycles in the introductory series of episodes exaggerate the preparatory stage of the film, a stage which has always been important for Anger, as in the waking and costuming sections of Fireworks and Inauguration, and suggest that a climactic show-down is forthcoming. The first intimation of disaster occurs in the third episode, also of motorcycle polishing and fitting, which opens and closes with views of a Grim Reaper skeleton in a black velvet hood surveying the cyclist and his machine. We hear the threatening lyrics of the song, “My boyfriend’s back and there’s gonna be trouble.…”

Anger once described his finding the fourth song as an example of “magick.” He said that he had completed the selection for all the other songs and needed something to go with this episode, in which three cyclists at different locations ritually dress themselves in leather and chains with the montage continually jumping from one to the other. Anger turned on his radio and exercised his will. Out came Bobby Vinton’s “She wore blue velvet,” which when joined to the episode created precisely the sexual ambiguity Anger wanted in this scene. In fact, there is a brief cut in the middle of the episode as one bare-chested cyclist leans forward toward the camera and the image switches to the crotch of another as he zips his pants, suggesting fellatio. Similar eroticized montages occur later in the film, as when the hero kisses the plaster scorpion, his totem, for good luck, and the image quickly cuts to the bare navel of another cyclist.

The next four song-episodes, forming the second part of the film or “The Image Maker,” as the notes call it, comprise its core and culminate in the “Heat Wave” and “He’s a Rebel” episodes, which represent Anger’s clearest and most intricate thought on the dialectics of reality and imagination. The previous part had ended as a fully-dressed cyclist wheeled his bike out of the garage. The sudden appearance on the screen of a frame of Li’l Abner comics introduces Scorpio, the hero of the film. We see him lying in bed reading the funnies as Elvis Presley sings “You look like an angel, but you’re the devil in disguise.” His room is a vast metaphor; its walls exhibit a virtual catalogue of his unconscious, in the same way that the cluttered walls of many American adolescents, where everything meaningful to them is tacked and pasted, represent the contents of the unconscious. Thus, without resorting to expressionism, as in the GENTs room of Fireworks, Anger shows us an iconographic space that is also a real space. On the walls are pictures of James Dean, Marlon Brando, and a Nazi swastika. There is also a television, turned on through the series of episodes in this room. It functions as an aesthetic reactor. Whatever we glimpse on it is always a metaphor for what is happening within the hero of the film. Its metaphoric level extends simultaneously as an aesthetic dimension of Scorpio’s thought and action in the realm of plastic illusion and as an icon of contemporary life—the source as well as the reflection of the unconscious. It is from the images on this television that Anger gets his most interesting collage effects.

After his own ritual costuming to the sound of “Hit the Road, Jack,” ending in his putting on rings quite like the opening of Inauguration, Scorpio takes a sniff of a drug, perhaps “crystal meth” or cocaine. Here we have an exultant image of Romantic liberation when the most interiorized of the songs in the film, “Heat Wave,” is combined with an image on the television of birds escaping from a cage, and then, amid two-frame flashes of bright red, a gaudy, purple picture of Dracula. We see in one or two seconds of cinema the re-creation of a high Romantic, or Byronic myth of the paradox of liberation. This brief montage evokes both tremendous liberation and tremendous limitation; the liberation inherent in the exuberant enthusiasm of the editing and the ecstatic pace of the music, and the simultaneous limitation in that the sudden “ace of light,” as Michael McClure calls a sniff of cocaine, comes from a bottle and a powder; it is exterior. The image of the monster is just a gaudy photograph, and the freed birds are in the end just a couple of pigeons on television. Although I have to describe these contradictory aspects of the cinematic experience sequentially, they occur simultaneously in watching the film.

From this point on, the entire film is structured around the interaction of contraries. In the “Heat Wave” episode the initial flash from the drug blends into images of his heroes. Scorpio is intercut with photos of James Dean. Marlon Brando appears on the television, in his motorcycle film, The Wild One. When we catch sight of him he has an interiorized smile, his eyes are closed, and he too seems to have just sniffed cocaine. When Scorpio puts on his jacket, we see the skull on the back of Brando’s.13

At the end of the scene, Scorpio repudiates his heroes; for Anger’s vision of the myth of the American motorcyclist argues passionately with the tepid social morality of Brando’s and Dean’s films. Next to the Promethean Scorpio, they are “bad boys” from Boys’ Town. So Scorpio draws his gun on a still of Gary Cooper from the show-down in High Noon, and he points it into the television, but Brando is no longer there; instead we see first a Hebrew menorah and then a crucifix as the objects of his attack. At this point he kisses the scorpion and leaves his room.

In the course of the film there is a transition from minor to major heroes, from movie stars to the charismatic powers who have shaken the world. The first example, which we meet in the coming episode, is Christ; the second, later, is Hitler. The gunning of the menorah and the crucifix established the context of interpretation for the following sequence. As the camera follows the boots of the hero through the street to the music of “He’s a rebel, and we’ll never know the reason why,” we are prepared for the comic highlight of the film. From Family Films’s The Road to Jerusalem, we see Christ parading past his followers. Like the heroes in photographs and on television, this Christ comes to us at one remove. The space abruptly shifts from the colored scenes of Anger’s photography to a flat, blue-tinted black-and-white image in the intercuttings. True to the high Romantic tradition, of which Anger himself may be only dimly aware, the heroic Christ is wrenched from the traditional Christian interpretation. Through the montage we learn what Scorpio would do if he were Christ, or perhaps what he thinks Christ really must have done: when Christ approaches the blind beggar, Scorpio would have kicked him, as he kicks the wheel of his motorcycle, and would have given him a ticket for loitering, as a cop places a parking violation on the bike; Christ touches the blind man’s eyes; through a very quick intercut we see that Scorpio would have shown him a “dirty picture”; and when the beggar goes down on his knees before Christ, Scorpio offers him his stiff penis.

Scorpio Rising is a mythographic film. It self-consciously creates its own myth of the motorcyclist by comparison with other myths: the dead movie star, Dean; the live one, Brando; the savior of men, Christ; the villain of men, Hitler. Each of these myths is evoked in ambiguity, without moralizing. From the photos of Hitler and a Nazi soldier and from the use of swastikas and other Nazi impedimenta, Scorpio derives ecstasy of will and power. Scorpio Rising is a more sophisticated version than Anger had ever before achieved of the erotic dialogue. In this film he is no longer describing the visionary search for the self, as he had in Inauguration, but presenting an erotic version of the contraries of the self.

In all but the last of the remaining five song-episodes, Anger continues to compare motorcyclists to Family Films’s Christ. Flashing lights in the spokes of a motorcycle introduce the “Walpurgis Party.” Here, to the music of “Party Lights,” the cyclists come in costume. One wears a skeleton suit through which his penis protrudes. Their entry is meshed with a procession of Hollywood disciples obsequiously accepting the invitation to enter a house. When Christ himself is seated, the song changes to “Torture” and his offscreen looks are intercut with the party to give the impression that he is supervising the members of the gang who have started to smear hot mustard on the bare crotch of one of their comrades. Scorpio has arrived at the party, but he quickly leaves to explore, with a phallically placed flashlight, a church altar, draped with a Nazi flag.

In the party episodes the camera movement is looser and faster than anywhere else in Anger’s work. In hand-held sweeps, it follows the pranks of the cyclists—dropping their pants, poking a woman with a bare penis, slapping each others’ asses like a tom-tom, sending someone pantless on his cycle out into the night, and pouring on the mustard. Toward the end of the “Torture” section, the camera regains its calm horizontal and vertical panning. A ceramic of Christ’s face passes the screen. Scorpio points downward from the altar, and the camera, following his finger, shows us quivering buttocks brutally beaten. In the initial version of the film, which has undergone very few important changes, a shot of a plastic bottle of “Leather Queen” stood where the sadistic image now appears.

In the final three sections of the film, Scorpio, still standing on the altar which he progressively desecrates, directs a motorcycle race in an open field. As the cyclists rev up their bikes at the starting line, Christ is hoisted onto a donkey side-saddle. It is “The Point of No Return,” as the accompanying song tells us. The hero, in a black leather mask with a Luger in one hand and a skull and crossbones flag in the other, signals the riders on. The one superimposition of the film occurs when the image of the scorpion hovers behind the waving death flag. In the second part of the race, to the song, “I will follow him,” Scorpio reaches the height of his demonic possession. The montage suggests that he is a diabolical Puck in a collage previously discussed. Before pictures of Hitler and pans over Nazi parade troops, he urinates in his helmet and holds it high on the altar as his offering. Then he kicks books off the altar and leaves in the night.

A pastel sketch opens the final scene. It is a skeleton head smoking a cigarette labeled “Youth.” At the sound of a cash register or a slot machine, a picture of Christ guiding a clean-cut young man appears in the skeleton’s eye socket. “Wipe Out” is the last song. The images are the most abstract of the film: a montage of Nazi pictures, flags, even swastika checkers. Briefly we see Scorpio with a submachine gun shouting orders. A cyclist crashes in the race and presumably dies. The final images of the film show a red flickering police car light rhythmically intercut with the face of a cyclist filmed in infra-red so that he too is red against a black background. The end title is written in studs on a leather belt.

Tony Rayns, in his analysis of the film,14 says that Scorpio is the motorcyclist who dies. I see no evidence for this. The death is the sacrifice that Scorpio demands. It, and not the winning of a race, has been the obvious culmination of the film from the beginning, as Pan’s sparagmos had been needed to inaugurate the pleasure dome.

In Anger’s booklet of notes on the Magick Lantern Cycle of i966 he provided the following schematic autobiography:

Sun Sign Aquarian

Rising Sign Scorpio

Ruling Planet Uranus

Energy Component Mars in Taurus

Type Fixed Air

Lifework MAGICK

Magical Weapon Cinematograph

Religion Thelemite

Deity Horus the Avenger; The Crowned and Conquering Child

Magical Motto “Force and Fire”

Holy Guardian Angel MI-CA-EL

Affinity Geburah

Familiar Mongoose

Antipathy Saturn and all His Works

Characteristic Left-handed fanatic craftsman

Politics Reunion with England

Hobbies Hexing enemies; tap dancing; Astral projection; travel; talisman manufacture; Astrology; Tarot Cards; Collage

Heroes Flash Gordon; Lautreamont; William Beckford; Méliès; Alfred C. Kinsey; Aleister Crowley

Library Big Little Books; L. Frank Baum; M. P. Shiel; Aleister Crowley

Sightings Several saucers; the most recent a lode-craft over Hayes and Harlington, England, February 1966

Ambitions Many, many, many more films; Space travel Magical numbers 11; 31; 9315

Formally, Scorpio Rising’s precursor (by a few years at most) was Bruce Conner’s second film, Cosmic Ray. Whether or not Anger had seen the film is hardly relevant here, as I can hardly believe it had a direct influence upon him. Nevertheless, Conner should be credited as the first film-maker to employ ironically a popular song as the structural unit in a collage film. The title of his film is a pun, referring both to Ray Charles, whose song “Tell me what I say” forms the sound track of the film, as well as to atomic particles from outer space. Conner intercut material which is primarily the irreverent dance of a naked woman, which he photographed himself, with stock shots from old war films, advertisements, a western, a Mickey Mouse cartoon, etc., ridiculing warfare as a sexual sublimation. The structure of the ideas evoked by Conner’s collage is straightforward; unlike Anger’s film, there is little room for ambiguity in Cosmic Ray.

In the sequence of Anger’s films, there is an evolution of forms from the late forties through the sixties which will recur again and again in the works of his contemporaries. The shift is from the trance film to the mythopoeic film. Both forms assert the primary of the imagination; the first through dream, the second through ritual and myth. Almost all of the filmmakers discussed so far in this book have moved through these two stages at almost the same time. The development of Maya Deren’s formal concern with cinema had been from dream (Meshes of the Afternoon) to ritual (Ritual in Transfigured Time) and myth (The Very Eye of Night). The cases of Peterson and Broughton are exceptional; they do not fit the pattern neatly, but that is because the former stopped making films in 1949 and the latter left the medium for so long before returning to it.

Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome was the first major work to herald the emerging mythic form in the American avant-garde film. In its initial form, in 1954, it was closer to Maya Deren’s concept of a cinematic ritual than to what would emerge in the 1960s as the mythopoeic cinema—Scorpio Rising, Markopoulos’s Twice a Man (1963) and The Illiac Passion (1968), Brakhage’s Dog Star Man (1961–1966), Harry Smith’s Heaven and Earth Magic (approx. 1950–1960). In that early version the Kabuki-like pace of the opening part extended throughout the film; its formal operation was like the choreography in Ritual in Transfigured Time. After Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, the mythic form emerged in Deren’s The Very Eye of Night (1958) and Maas’s Narcissus (1958). In all three instances the film-makers sought to represent specific myths and mythological figures. The triumph of the mythopoeic film in the early sixties sprang from the film-makers’ liberation from the repetition of traditional mythology and the enthusiasm with which they forged a cinematic form for the creation or revelation of new myths. Scorpio Rising is an excellent example of this new vitality.

Immediately after the success of Scorpio Rising, Anger tried to apply the very same formal invention to a similar theme, the custom car builder. Early in 1964 the Ford Foundation experimented with giving a few independent film-makers grants of ten thousand dollars. After their initial grants, they discontinued the experiment. Anger was fortunate enough to be among the recipients. With his money he made some slight revisions of Scorpio Rising, created the Sacred Mushroom version of Inauguration, and began Kustom Kar Kommandos. The film was never completed. In 1965 he showed an episode, similar to some of the opening scenes of Scorpio, in which a young man polishes his finished car with a giant powder puff. The pastel colors and the fluid movement (the car seems to be turning on a giant turntable) are even richer than similar effects in his previous film. Like Scorpio, too, this episode had as its soundtrack a single rock and roll song, “Dream Lover.” At the end of the sequence as he showed it, Anger appended an appeal for funds to finish the film. Those funds never appeared and Kustom Kar Kommandos was abandoned. Anger has left its one episode, resuscitating the form of the fragment as he had done when he distributed Puce Moment from Puce Women.

Fortunately a prospectus survives for the complete KKK. It is reproduced here in its entirety. It is interesting to note that the “Dream Lover” segment is not to be found within it:

“KUSTOM”

(KUSTOM KAR KOMMANDOS—FILM PROJECT)

Film project by Kenneth Anger utilizing the Eastman rapid color emulsion Ektachrome ER, whose ASA rating of i25 opens up hitherto inaccessible realms of investigation in low-key color location work for the independent creative film-maker. Running time 30 minutes, track composed of pop music fragments combined with sync location-recorded sound effects and dialog.

KUSTOM is an oneiric vision of a contemporary American (and specifically Californian) teenage phenomenon, the world of the hot-rod and customized car. I emphasize the word oneiric, as kusTom will not be a “documentary” covering the mechanical hopping-up and esthetic customizing of cars, but rather a dreamlike probe into the psyche of the teenager for whom the unique aspect of the power-potentialized customized car represents a poetic extension of personality, an accessible means of wishfulfillment. I will treat the custom cars created by the teenager and his adult mentors (such customizers as Ed Roth, Bill Cushenberry and George Barris, whose Kustom City in North Hollywood is a mecca of this world) as the objects of art—folk art if you prefer—that I consider them to be.

The aforementioned adult “mentors,” most of whom are located in the periphery of Los Angeles and hence readily accessible for filming, will be shown at work in their body shops on various cars-in-the-process-of-becoming, in the role of “arch-priests” to the teenagers whose commission they are fulfilling. (The locales of body shops and garages will be presented uniquely in gleaming highlighted low-key, in a manner already essayed for the motorcycle garage locations of SCORPIO RISING); the idolized customizers (the only adults seen in the film) will be represented as shadowy, mysterious personages (priests or witch-doctors) while the objects of their creation, the cars, will bathe in a pool of multi-sourced (strictly non-realistic) light, an eye-magnet of nacreous color and gleaming curvilinear surfaces.

The treatment of the teenager in relation to his hot-rod or custom car (whether patiently and ingeniously fashioned by himself, as is usually the case, or commissioned according to his fantasy, for the economically favored) will bring out what I see as a definite eroticization of the automobile, in its dual aspect of narcissistic identification as virile power symbol and its more elusive role: seductive, attention-grabbing, gaudy or glittering mechanical mistress paraded for the benefit of his peers. (I am irresistably drawn to the comparison of these machines with an American cult-object of an earlier era, Mae West in her “Diamond Lil” impersonations of the Thirties.)

The formal filmic construct of KUSTOM is planned as follows: (The division into titled “sections” is uniquely for working convenience; these divisions will be “erased” in the finished work.) The dominant pop record is indicated in capitals.

1.HAVE MONEY (The Young Conformers.) An introduction insinuating the spectator into the teen-dream. A fast-shifting visual reverie utilizing the linking device of the lap-dissolve and the wipe to establish patterns of convention followed by the teenage (and sub-teen) group: similarity of hair-styling, style of dress, of language, attitude or manner, taste in dance patterns and pop music; the omniscience of certain popular heroes or ever-shifting masks on Archetypal Images.

2. DAWN (Crystalization.) The concept of individual “style” dawns upon the Teenager. The carefully composed aerodynamics of a crested coiffure as it is formed. The love-lock. Racked sideburns. The embroidered, self-identifying jacket or painted Tshirt. The “far-out” color combinations in stove-pipe pants, shock-effect shirts and socks. The Grail: the vision of the Teenager as Owner of his own, screamingly individualistic, unique and personalized custom car. (These images of the Grail, “the goal,” will be floated across the mirrored image of the Teenager as he arranges his coiffure or clothes.) Subliminal flashes as [he] thumbs through hot-rod magazines or plays juke-box. Closeups of high-school desk tops showing open text books (Science or History) while adolescent hands doodle, first crudely, then with increasing refinement, silhouettes of hot-rod and custom “dream” cars.

3. THENITTY-GRITTY (Realization.) The Teenager attacks. Dream into action. Abrupt change in formal construct: sharp cuts, swift pans, darting dollies. The night-lit junk-yard, weird derelict cemetery: lifting a “goodie.” The first jalopie: a rusty junked car pushed into the dark initiatory cave of the garage. Series of car-frames in the process of being stripped: an almost savage dismantling (analogy to wild animals dismembering a carcass).

4. MY GUY (The Rite.) Under the occult guidance of the shadowy, mysterious adult customizers performing as Arch-Priest, the Teenager’s Dream Car is born (allusion to obstetrics). The alchemical elements come into play: phosphorescent blue tongue of the welding flame, cherry glow of joins, spark shower of the buffer. Major operation: dropping the front, raising the back of the car, “channeling” and “chopping.” The Priest-Surgeon (customizer) perfects the metal modulations from cardboard mockups; plunges in with blowtorch and mallet. The swooping sculpted forms (blackened and rough) materialize in closeups and their intent is perceived.

5. IN HIS KISS (The Adorning.) Sudden darting color: the rainbow array as cans are opened, stirred dripping gaudy sticks held up for the Teenager’s contemplation and approval. The iridescent “candy-flake” colors and shock-jewel tones in vogue. The Teenager chooses his color: tension, decision, joyful release. The cult-object—the shaping-up car body—in the swirl of colored spray-gun mists: rose and turquoise fluorescent fogs as coat upon carefully-stroked, glittering coat, the car-body emerges as a radiant, gem-hued object of adoration. A reflected color-bath splashes over the absorbed faces of the watching teenagers: a whoop of triumph, a jungle-stomp of joy as the custom car is “born.”

6. WONDERFUL ONE (Possession.) The Teenager takes possession of his own completed custom or hot-rod car: the painted finish is caressed, the line admired (as would be the line of a girl friend) the chromed shift fondled, firmly grasped. (For this kaleidoscopic montage involving scores of custom and hot-rod cars, it is hoped to include the outstanding examples of customizing currently touring America in the Ford Custom Car Caravan, which could well represent the ideal Dream Cars of America’s custom-conscious teenagers. However, for their appearance in KUSTOM, it will be necessary to film them in movement against unified black or nocturnal backgrounds—an effect that can be accomplished by camera or optical artifice if it proves impractical to night-drive these valuable machines.)

7. THE RUGITIVE (Flight and Freedom.) The Teenage hotrodders “rev up” (The Syndrome of the Shift) and take off for a nocturnal drag race (irreal colored light-sources throughout). A lone hot-rodder races down a curving mountain road (Dead Man’s Curve). The Custom Boys, in slow motion, take command of the controls of their Dream Cars. (This concluding sequence of KUSTOM operates exclusively in the realm of “dream logic”: it is intended to create a Science-Fictional atmosphere.) The hot-rodders experience the erotic power-ecstasy of the Shift (the Hurst shift will be employed) to the magnified accompaniment of motor and exhaust. The Custom Boys resemble Astronauts at their controls: their vari-hued craft seem to lift into space. (If possible, a prototype of an actual “air-car” by a noted West Coast designer will be utilized in this section.) The Dragsters streak down the search-light stabbed runway (ideally seen by helicopter) as in cross-cutting the Custom Boys are liberated into weightlessness with their strange craft, and plunge starward.

8. SHANGRI-LA (Apotheosis.) The Dragsters streak towards an imposing podium (by montage inference) piled high with towering, animated trophies of glittering gold; the Custom Boys range above the golden mountain high and free. A nocturnal jostling cheering crowd of teenagers (lit by swinging stabbing searchlights) swing up on their shoulders The Winner—Mr. Hot-Rod, his glowing triumph-filled countenance streaming sweat, his bare arms bearing his Golden Trophy Tower—he exults as The Conqueror, drinks in the adulation of the adolescent sea around him; he is startled by the sky-borne vroom of the upward-sweeping Dream Cars, his beaming face swiftly mirroring, in the moment of his triumph, a greater wonder, a greater goal. END

Anticipation of KKK gradually faded in the late sixties as Anger made statements about his new project, Lucifer Rising, which was to be his “first religious-film.” Before the theft of his footage in 1967, Anger had faced two major crises while he was trying to make the film in California. His first “Lucifer,” a five-year-old boy, killed himself trying to fly off a roof; his second, Bobby Beausoleil, was convicted of murder. In addition to this, there was the perpetual financial struggle.

In several interviews he contrasted the project for Lucifer Rising with Scorpio Rising as films about the life force and the death force respectively. “It’s about the angel-demon of light and beauty named Lucifer. And it’s about the solar deity. The Christian ethos has turned Lucifer into Satan. But I show it in the gnostic and pagan sense.… Lucifer is the Rebel Angel behind what’s happening in the world today. His message is that the Key of Joy is disobedience.” Anger has also described his encounter with a demon, Joe, who got him to sign a contract in blood and disappeared after providing him with information that would help him to make the film. According to the early reports, Lucifer Rising was to be about the “Love Generation” in California, hippies, and the magical aspects of the child’s universe.

The first sign of the rejuvenation of his film-making in the 1970S was his completion of Invocation of My Demon Brother, which includes material from the original Lucifer Rising. Then he released Puce Moment, synchronized to a new song, and finally he finished La Lune des Lapins, having re-edited the material after twenty years, added a set of songs, and translated the title to Rabbit’s Moon.