AMONG THE HIGHEST achievements of Brakhage’s art since the spectacular series of lyrical films in the late 1950s and early 1960s have been three long or serial films, Dog Star Man (or in its expanded form, The Art of Vision), Songs, and Scenes from Under Childhood (itself the first part of a projected autobiography, The Book of the Film). Likewise Baillie had proceeded from lyric to epic with the making of Quick Billy, which holds a position in the evolution of his work comparable to that of Dog Star Man in Brakhage’s.

The writing of Metaphors on Vision coincided with the shooting and editing of most of Dog Star Man. Brakhage seems to have started both around 1960. The book was published at the very beginning of 1964; the five-part film was completed by the end of that year and had its first screenings in 1965. Here more than at any other point in Brakhage’s career his aesthetics throw light on the film. Nevertheless the critic must be careful not to let the film-maker’s glosses completely dominate his viewing of the film. An oversubscription to Brakhage’s paraphrases has blinded at least two published interpretations of the film to some of its complications.1

Dog Star Man elaborates in mythic, almost systematic terms, the worldview of the lyrical films. More than any other work of the American avant-garde film, it stations itself within the rhetoric of Romanticism, describing the birth of consciousness, the cycle of the seasons, man’s struggle with nature, and sexual balance in the visual evocation of a fallen titan bearing the cosmic name of the Dog Star Man.

From two interviews, one published as the introduction to Metaphors on Vision and another unpublished one now in the Anthology Film Archives library, we can construct his argument for Dog Star Man:

The man climbs the mountain out of winter and night into the dawn, up through spring and early morning to midsummer and high noon, to where he chops down the tree…. There’s a Fall—and the fall back to somewhere, midwinter.

I thought of Dog Star Man as seasonally structured that way; but also while it encompasses a year and the history of man in terms of image material (e.g. trees become architecture for a whole history of religious monuments or violence becomes the development of war), I thought it should be contained within a single day.

I wanted Prelude to be a created dream for the work that follows rather than Surrealism which takes its inspiration from dream; I stayed close to the practical use of dream material…. One thing I knew for sure (from my own dreaming) was that what one dreams just before waking structures the following day…. Since Prelude was based on dream vision as I remembered it, it had to include “closed-eye vision.”

In the tradition of Ezra Pound’s Vorticism, Part One is a Noh drama, the exploration in minute detail of a single action and all its ramifications. [Brakhage described the basic action of this section as “the two steps forward, one step backward” motion of the hero, which he related to the forward-backward motion of blood in the capillary system, the final image of that part.]

The heart had stopped in Part One, and, while we see an increasingly black and white image [of the man] that climbs up the mountain, there is a negative image of the Dog Star Man that is absolutely fallen at that instant.

I had no idea what would happen in Part Two, except that it would be in some sense autobiographical; but I knew that the heart must start again in Part Three; and that it would be a sexual daydream, or that level of yearning, that would start the heart again.

The moment at which the man is seen both climbing and fallen is recapitulated in a way at the beginning of Part Two.… I reintroduced the man climbing both in negative and positive, superimposed. I had some sense that these twin aspects of the Dog Star Man could be moving as if in memory.… I realized that the man, in his fall and his climb in negative and positive, was split asunder and related either to himself as baby (those first six weeks… in which a baby’s face goes through a transition from that period we call infancy to babyhood;… the lines of the face fill out what might be called a first mask or a personality, a cohesiveness which occurs in the facial structure or control of the face over those first six weeks) and/or to his child.

The whole idea of the baby’s face achieving a solidity, or the first period of birth would relate metaphorically to spring, the springing into per-son.… At the end of Part Two a balance is achieved when the images return to the Dog Star Man in his fall. It was very important to me, too, that the tripod legs would show in the distance so that there is always some sense that this is a film-maker being filmed.… In no sense is it engaging or pulling in, precisely because in the plot level of the film the Dog Star Man is being engaged with his own childhood by his child….

The images return to the Dog Star Man in his fall, in his jumps back down the earth, or his imagined fall. He’s seen finally flat on his back on a rock ledge and the figure of the woman is collaged in.

Part Three has a “His, Her, and Heart” roll…. Female images are trying to become male and have not succeeded and the males are trying to become female and have not succeeded…. In the “Her” roll you see mounds of moving flesh that separate distinguishably into a woman’s image, but then become very tortured by attempts to transform into male. It’s very Breugelesque in a way; penises replace breast in flashes of images; then a penis will jut through the eyes; or male hair will suddenly move across the whole scape of the female body.… At some point this ceases and this flesh becomes definitely woman. Then on the “His” roll… you have the opposite occurring: a male mound of flesh which keeps being tortured by a proclivity to female imagery; so that, for instance, the lips are suddenly transformed into a vagina. Finally the male form becomes distinct. Then, of course, these two dance together as they are superimposed on each other; you get this mound of male-female flesh which pulls apart variously and superimposes upon itself in these mixtures of Breugelesque discoveries, so to speak, or distortions. Finally toward the end, the male and female become separate so that they can come together.

Part Four begins with that man on the ledge as we found him at the end of Part Two. He rises up and shakes off the sexual daydream and becomes involved in shaking off every reason he might have for chopping that tree.… Finally, if looked at carefully; there is really no relevant, definite, specific reason given for that Dog Star Man to chop the tree as he does at the end of Part Four…. Finally the whole concept of the woodcutter gets tossed into the sky.… The axe is lifted up and the figure cuts to Cassiopeia’s chair, which I suppose you can say is finally what Dog Star Man sits down into in the sky.… The whole film flares out in obvious cuts which relate in their burning out and changes of subtly colored leader to the beginning of the Prelude.

Brakhage’s paraphrase suggests at times a narrative consistency which is not apparent in the film, while he omits other obvious connections. Part One clearly situates itself in winter, while Part Four begins with images of summer and proceeds along an alternation between summer and winter until its end. The seasonal system, as Brakhage outlines it, refers to the dominant metaphors of the parts, not to their total visual presences. In Part Two we see the visual, aural, and haptic reactions of an infant (the mediator of spring) and in Part Three the superimposition of naked male and female bodies with a beating heart and paint splatter. Part Three is an erotic version of the myth of summer’s richness. Finally, in Part Four, the images of the protagonist literally falling from summer work to winter desolation elliptically suggest the transitional season of fall and mimetically echo its processes.

Yet more striking than the problem created by Brakhage’s claims for the seasonal interpretation of the film is the difference between the actual function of Parts Two and Three in the film and in the film-maker’s account of them. It is true that the heart slows down at the end of Part One (but it does not stop) and that it accelerates at the conclusion of Part Three. Yet the fallen Dog Star Man of Part One appears vigorously climbing upward again at the beginning of Part Two, and he is seen both climbing down and fallen at the end of that section. In fact, the opening and concluding climbs distinctly bracket the entire episode of the infant’s sensibilities. Brakhage’s reading of the film fails to account for this and substitutes in its place a much more obscure connection, that of the heart rates. Actually, Part Two and Three have a dialectical relationship to each other. They are alternatives or aspects of the divided titan. He postulates two forms of privileged vision, the innocent and the orgasmic. In the earlier films, as we have seen, Brakhage describes the urgency of the need for unschooled vision and for erotic fulfillment, although not in a single film. In Loving there is a hint that the former can be born of the latter. With the idealization of the infantile and the orgasmic vision goes a severe skepticism about their adequacy.

It is at this point that Brakhage’s perspective most closely coincides with Blake’s, who at various moments in his development speaks of four realms or states of existence. The first, Beulah, or Innocence, encompasses the vision of the child; next Generation, or Experience, defines the adult world of titanic sexual frustration and circumscribed erotic fulfillment; only the minor appendages, the sexual organs, can unite in Blake’s derisive vision, while the whole body cries out for a merging of male and female. Northrop Frye describes one relation of Innocence to Experience thus: “As the child grows up, his conscious mind accepts ‘experience,’ or reality without any human shape or meaning, and his childhood innocent vision, having nowhere else to go, is driven underground into what we should call the subconscious, where it takes an essentially sexual form.”2 The third and fourth states are respectively the damned and liberated alternatives to the two-fold opposition of innocence and experience. They are Ulro, the hell of rationalism, self-absorption, and the domination of nature; and Eden, the redeemed unity realm of “The Real Man, the Imagination.”

The image of the child is complex in Brakhage’s films.3 In Anticipation of the Night it evokes innocence lost, and the whole film alternates between the minor pastoral and the major elegiac. But Dog Star Man aspires to the more elaborate mentality of Metaphors on Vision, in which the child can be a guide, or a warning, but not an end. On the first page he writes:

Once vision may have been given—that which seems inherent in the infant’s eye, an eye which reflects the loss of innocence more eloquently than any other human feature, an eye which soon learns to classify sights, an eye which mirrors the movement of the individual toward death by its increasing inability to see.

But one can never go back, not even in imagination. After the loss of innocence only the ultimate of knowledge can balance the wobbling pivot.4

Behind the puns, name-dropping, and quotations of “Margin Alien” rests the idea of an anagogic unity of literary and painterly imagery. In his writing and speaking about Dog Star Man there is a tension between the argument of the film as he conceived it before shooting, while making it, or after it was finished, and the aspects of the film which were revealed to him at any of these stages. That the outline changed during the seven years between its inception and completion he makes quite clear:

I always kept the growth of Dog Star Man consonant with the changes in our living. I never let an idea impose itself to the expense of actually being where I was when I was working on the film. I never built, or permitted any ivory tower to get built around myself so that I could pursue the original idea of Dog Star Man to the expense of keeping that work from changing in detail according to the life we were living.5

The dialectic between the clarity of design and the vicissitudes of the filmmaking process accounts, in part, for the fact that someone as articulate and insightful as Brakhage could be blind to the way in which Part Two and Part Three of his film function as paired interludes in the texture of the work. In these two sections of almost equal length, which are visually distinct from the unity of Prelude, Part One, and Part Four (and different from each other), Brakhage, like Blake, describes the sources of renewal as an innocence of the senses and erotic union, and, again like Blake, suggests that alone each is insufficient and that together they open the still very difficult possibility of physical and spiritual resurrection.

The film is quite specific about that difficulty. After the interludes of Parts Two and Three, Part Four, which rushes to its conclusion in five minutes of very rapid montage on four layers of film, begins with the fallen figure and shows him alternately chopping the tree in the heat of the summer sun and wandering, stunned from his fall, through the winter forest of Part One. The resolution of the film is not a Blakean liberation into Eden and reunion of the imaginative and physical division. Brakhage at this point follows the post-Romantic substitution of tautology for liberation: in their major poems, “Un Coup de Dés” and “Notes toward a Supreme Fiction,” Mallarmé and Stevens triumphantly proclaim the failure of the divine within or without man; instead they posit a teleology of poetry, and in their wake Brakhage ends his film with a naked affirmation of his materials and his mechanics. The images dissolve in projected light; the chopping of the tree becomes a metaphor for the splicing of film. The apotheosis which Brakhage describes (Dog Star Man assuming Cassiopeia’s throne in the sky) appears but for a second on the screen and it is not the last image of that figure. We see him furiously chopping again, which qualifies the stellar image into an idea, a possibility, or a desire.

Prelude begins with a greenish-gray leader in which faint, shallow, shimmering changes of texture gradually appear. Out of this abstract chaos images of the sky, snow, fire, and streetlights emerge, sometimes slowly and sometimes suddenly. As the eye is teased by the speed and shifting focus of these initial elements, it becomes apparent that the montage is in the service of a double metaphor; the opening of the film seems like both the birth of the universe and the formation of the individual consciousness.

The entire film is formed of two superimposed layers of images, but at times, such as at the very beginning, there are visual silences on one or both layers which either allow one image to assume the presence it would on unsuperimposed film or present a vaguely lit visual field on the screen. For the most part the superimposition reinforces the basic flatness of the images in the Prelude; compositions-in-depth are extremely rare; and often Brakhage uses filters, distorting lenses, and a moving camera to create a two-dimensional space for his images. Finally there are numerous instances of painting or scratching over one or both layers, making the superimposition virtually three- or four-fold.

Early in the film, shots of the bearded, long-haired Dog Star Man are glimpsed, along with fragmentary pictures of his dog and the moon. Both by superimposition and by montage Brakhage compares the movement of clouds with the flow of the blood in magnification. From this point on, a rhetoric of metaphor is established, mixing micro-and macro-cosmic images with varying degrees of explicitness.

In the first third of the film, after the initial movement of the consciousness in which images become more concrete and steadier on the screen, an evolving sequence concentrates on shots of the moon through a telescope and coronas of the sun, while the figures of the Dog Star Man and the woman are introduced as a theme of the development.

The forms of superimposition are numerous: explicit illusionism (the moon moving through the Dog Star Man’s head); reduplication; conflicts of scale (the sun’s corona over a lonely tree); conflicts of depth (the masklike face of the hero over a deep image of a city street at night); color over black-and-white (bluish waves on the white moon); one distinct and one blurred figure; finally, the superimposition can recur synchronously, two images at a time, or, as is more usual, the alternations may be staggered, eliding the changes.

Following the sun and moon sequence with its simultaneous introduction of the male and female figures, the images settle on earthly subjects. The mountains and a solitary house appear. In this central scene we see much more of the Dog Star Man himself. After an interlude of unraveling landscapes with expositions of internal organs, especially the heart, comes the most concentrated episode in the film: here we see the Dog Star Man struggling with the tree—the central act of the film according to the film-maker’s argument. Significantly, this is the one important episode which occurs only in the Prelude. For the rest of the film, that moment of confrontation, hinted at here, is the central absent vortex around which the actions revolve. Actually Brakhage himself had not known that the struggle with the tree would occur only in the Prelude, even after he finished that section in 1961. At that time he was talking as if it would be elaborated in the summer vision of Part Three, which he had not yet begun to structure.

As we watch the film the tree episode suddenly appears to crystallize within seconds, both layers seemingly devoted to its exposition. While he shakes the tree as if uprooting it, the camera zooms in again and again on the roots, comparing them once to a female crotch, and the immediately subsequent chopping of the tree repeats the rhythm of the zoom. Almost as suddenly as the scene materialized, it dissolves, and the idea of a family emerges, with shots of the Dog Star Man holding a baby and kissing the woman, and of her breast-feeding the baby.

In its final third, Prelude re-establishes its emphasis first on the sun, now seen with a tremendous eruption of surface scratches, imitating the flares; then the landscape variations reaffirm their presence, including now for the first time a burned forest with Greek columns superimposed (explicitly postulating the origin of that architectural development). Unlike most Brakhage films, including the other sections of Dog Star Man, Prelude has neither a climactic nor a diminuendo ending. The suddenness of the termination may be a concession to the structure of dreams that Brakhage says inspired the form of this film.

He has described how, after he shot what he thought would be all the material for the whole film, he did not know where to begin editing. He therefore pulled material willy-nilly from the unorganized rushes and edited thirty minutes by chance operations. Looking at this random film, Brakhage had a new insight into the material. He then consciously edited a parallel strip of film in relation to the original chance roll, as if commenting on it. When at times that method failed to produce a coherent vision, he re-edited a section of the randomly composed roll. Knowing this method, we better understand how the film moves in waves from closely knit forms to vague ones. The opening and the tree section seem to have been deliberately structured on both levels. The rising and falling of rhythms and clustering and dissolving of scenes must, then, be a function of the tension between the chance and conscious layers of the film.

Although the images of Part One proceed from Prelude, that section is formally antithetical to its predecessor. In Prelude Brakhage built a pyrotechnic, split-second montage with as much varied material as he could force into half an hour. Part One is a tour de force of thematically constructed material stretched out to occupy the same amount of screen time. The film organizes itself, not around a nonstop series of metaphors and transformations, but in a number of more or less distinct paragraphs (more distinct at the beginning and end, less so in the center) punctuated by an unusual number of faces for Brakhage.

Ezra Pound, in his book Gaudier-Brzeska, which Brakhage read and identified as a primal source for this part, wrote:

The image is not an idea. It is a radiant node or cluster; it is what I can, and must perforce, call a VORTEX, from which and through which, and into which ideas are constantly rushing.6

I am often asked whether there can be a long imagist or vorticist poem. The Japanese, who evolved the hokku, evolved also the Noh plays. In the best Noh the whole play may consist of one image. I mean it is gathered about one image. Its unity consists in one image, enforced by movement and music.7

The opening “paragraph” of images seems to both encapsulate and reorganize the cosmology of Prelude: the first ten shots, generally much longer than any in the former section, gradually define a particular point on the earth’s surface from the stellar perspective. Three long shots of the moon partially obscured by moving clouds open the film. Then two shots of clouds alone gradually reveal earthly mountains. Continuing the rhythm but not the logic of the sequence, a white flame retreats into a burning log, followed by a flash of whiteness, and then by a very slow shot of frost disintegrating on a window pane into the shape of a hill or mountain as the image fades out. Finally a pulsating corona of the sun shimmers with explosions and issues a climactic burst. A very brief flash of clear leader punctuates the transition to the next paragraph.

The effect of the opening is to move from a position beyond the earth to a specific terrestrial location and then further to a synecdochic evocation of a dwelling (the window), which is also a metaphor for the hilly terrain; then back out, even further than the starting point, beyond the moon to the sun. Visually, the transitions are all consistent and smooth; colors when they appear at all are washed out or subdued. Finally, the entire texture of imagery familiar from the Prelude has a new presence and grandeur because of its lack of superimposition—there is virtually none in Part One—and the slowness of the montage.

The next grouping of eight shots introduces the Dog Star Man and the central action of the section: his arduous climb up a snow-covered mountain. For the first time in Dog Star Man the camera is so placed as to articulate a depth on the screen. The protagonist climbs up along a slanted plane or moves diagonally upward across the screen against a background of distant trees and mountains. Again Brakhage’s mention of Gaudier-Brzeska proves a useful clue: his manifesto, Vortex, quoted in Pound’s book, begins with “Sculptural energy is the mountain.”8

Nowhere else in all of Brakhage’s cinema is the antagonism of consciousness to nature so naked as in Part One. The mediator of this agon, the Dog Star Man, seems through most of the film to be defeated by the cold, the slope, and the tangles of trees in his way. Yet as the film progresses, the formal mechanics by which the myth is rendered come more and more to invade the metaphysics of the myth. First, without breaking the rhythm of the slow fades, the film-maker introduces a shot of the hero in greenish negative tossing as if in sleep, suggesting in a most tentative way that the climb itself might be a dream.

The sleeper fades into the arc of the moon, which in turn fades into the first section in which subjective camera positions occur, as if through the eyes of the climber in his struggle. Now hand-held shots of the sun, rushing water, and his hand gripping the snow as he slips are mixed with the filtered objective shots of him inching his way up the mountain. Amid pans of the landscape and blurs which begin to disrupt the even tempo of the opening topology appear images of blood, tissues, and internal organs—an exposition of what is inside the Dog Star Man.

As more and more impressionistic camera work is used, Brakhage achieves a uniquely cinematic tension. There is a dual realization that a particular shot is meant to suggest the Dog Star Man’s state of mind or what he is seeing, and that the same shot is a camera trick. For instance, he sees mountains writhing against the sky. That effect is rendered by the flagrantly obvious twisting of an anamorphic lens.9 The paradoxical tension between mechanics and illusion is integral to the structure of the section and increases both in the rapidity of instances and the degree of obviousness as the film draws to its conclusion.

The merging of perspectives and the acceleration of metaphor attend a flattening of the depth of the images and a general abstraction of all that we have seen so far. Pound defined Vorticism as follows:

Every concept, every emotion presents itself to the vivid consciousness in some primary form. It belongs to the art of that form.… It is no more ridiculous that a person should receive or convey an emotion by an arrangement of shapes, or planes, or colours, than that they should receive or convey such emotion by an arrangement of music notes.10

He is approaching the concept of vortex as “the point of maximum energy. … There is a point at which an artistic impulse is visceral and abstract and can be realized in any of the arts.”

The development gradually glides into the finale through a meditation on snow: the falling snow becomes the smoke of a forest fire; the hero shakes snow off branches as he clears his way with his axe; there is a single-frame animation of magnified snow crystals. As this section blends into the finale, the precision of the opening groupings returns. There are six separate phrasings of images in the finale of Part One. The first begins with the protagonist climbing up a slight incline with the dog moving easily by his side. As the finale progresses, the man seems to move more and more slowly. Appropriately, by the end he has almost stopped. He climbs from the other side of the screen at the same incline and then falls.

The second phrase is only two shots: the Dog Star Man climbing at a forty-five-degree angle, and a subjective shot of him falling. Then whiteness. The next section is again at a forty-five-degree angle; he falls. But the shot is cut short just as his dog begins to move in slow motion.

The fourth paragraph is the most crucial in the finale. He makes his way up a sixty-degree incline. The angle is so steep it poses the question, is the mountain just the function of a tilted camera? The next shot, a seventy-degree angle, answers affirmatively; for the dog, with magnificent grace, easily glides up to his master’s side, either defying gravity or demonstrating the tilt. At this point the terms of the opposition of nature and consciousness have been reversed. Although he is still defeated, the Dog Star Man is less the victim of nature than of his own or the film-maker’s imagination. In the fifth grouping, he is lying in the snow, first in positive, then in negative. He pulls himself up a ninety-degree cliff as Deren had pulled herself from the bench to a table in At Land. Having admitted the camera trick with the dog’s leap, Brakhage triumphantly exaggerates it. Throughout the film, images of the protagonist’s interior (heart, blood, tissues) and postulations of his “negative” self have become progressively more frequent and important. The final shot confirms the shift to an interior view: after a very long period of whiteness, the sixth phrase, a single shot, appears. It is a microscopic view of blood in a capillary vessel with its natural long push forward, short push back, long push forward motion.

Coming at this point the final shot illustrates the principle Brakhage derived from his study of idiotoxic disorders: that there is a physiological basis for a nexus of imaginative acts. Thus the rhythm of the blood corresponds to the winter rhythm of the Dog Star Man’s struggle with nature.

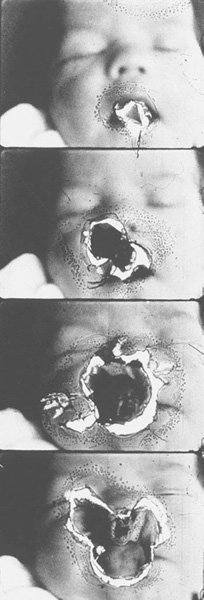

In Part Two, at first he climbs downward away from the camera, then suddenly forward, up and beyond the camera. After the momentary introduction of the crying baby, he appears again, now in color, stumbling among mountainous rocks. As he gropes past one of them, the camera settles upon it. The surface of the rock becomes the first major element of the superimposition upon the baby. Texturally, the images of the baby are not like anything we have seen so far in this film. Brakhage originally intended to make a short film called Meat Jewel about the changes of expression in the face of his first son during the initial six weeks of his life. He employed the technique of Mothlight in constructing this film—that is, he punched holes in the images and carefully inlaid other film material, holding the mosaic together with a covering of mylar tape. As the child screams in black-and-white, the mouth cavity is replaced by fragments of colored film. At another point, his sense of hearing is emphasized by the insertion of a colored ear in the hole made by cutting out the blackand-white original.

The inspiration of this short film, which became fully incorporated into Dog Star Man, had been the film-maker’s meticulous observation of the changes in facial structure of his first three children, all girls, and a poem, “The Human Face,” by his friend Michael McClure, from which the working title was derived.

Brakhage zooms in repeatedly on the screaming infant as if moving the camera in sympathy with his cries. Later he concentrates on his blinking eyes and the twitching muscles of his face. As a development of this instance, he inlays the colored ear. Lastly, he watches the spasmodic movements of the feet and hands. The effect of these scenes is to present a catalogue of the senses: the birth of sight, of hearing, and the haptic complex evoked by the kicking feet and waving fists.

Superimposed upon the collaged images of the baby are a series of flat colored images, reminiscent of parts of Prelude, passing very quickly. The predominant object is the rock mentioned above. It is presented in a flickering light which emphasizes its porous texture and suggests the kind of pre-verbal cognition possible to the newborn child. Compared to the rock are the visual textures of light passing through trees, the sun seen through a gauze, rushing blood, and the flesh of a nipple. A striking metaphor occurs in the superimposition when the dripping milk from that nipple seems to be a tear in the baby’s eye.

The end recalls the beginning, with superimposed solarized scenes of the hero climbing and colored shots of him fallen. As he lies on the ledge, a yellow, filtered shot of the nude woman is collaged over him, as if she were an emanation. The ragged edge of the inlaid material which is superimposed over him on the matching layer connotes the privileged status of the female aspect of his self—or his Emanation in Blakean terms—while at the same time reaffirming the illusory nature of the cinematic material.

The solid-color nude figure is familiar from the Prelude, but it is actually with Part Three that we associate these images; for that section, the most visually unique of the film, is composed entirely of colored nude images of parts of the male and female body superimposed over each other, while a heart and hand-painted smears (predominantly blue, green, and red) are superimposed over both. The combined effect is of a hermaphroditic sensuousness, rhythmically punctuated by the accelerated splashes of paint and beats of the heart. As the section moves to its end, the bodies become more abstract, as if the camera were very close to the flesh. The color changes become less intense, and thereby the presence of the heart, which had been minor at the opening, comes to predominate.

Here Brakhage’s interpretative description of the film fails to illuminate what we see. The synchronous superimposition blurs any distinction between “a male level becoming female” and “a female level becoming male.” We see, all at once, a thick interweaving of male and female bodies, and that’s all. The occasional appearance of a hand fingering the penis fails to qualify the whole episode as a mediator’s “sexual daydream” with any of the precision with which the first three sections were mediated.

After the alternative interludes of Parts Two and Three, Part Four recommences from the action of the frames of Part One and Part Two. This is the shortest (five minutes), most intricate, and most elliptical of the sections. The four layers of imagery provide an exceptionally dense viewing experience and make it difficult for the analyst to describe the film. Nevertheless Brakhage has often reduplicated his images two- and threefold, creating an echo or fugue-like effect, in which one act repeats itself in different colors and at slightly asynchronic intervals.

The film opens with several images, one on top of the other, of the Dog Star Man slowly rising from the supine position he was left in at the end of Part Two. Horizontal anamorphosis accentuates his outstretched body. His gestures, on the different levels, suggest both that he has risen from the dead and that he has awakened from a night’s sleep. While he is still rising on some of the echoing layers, we see the first of many shots of him chopping the felled tree. This is clearly a midsummer image, as he perspires, wipes his forehead, and continues his vigorous chopping in the noon sun. The montage reinforces the notion of resurrection. As the film progresses the gesture of chopping will assume a series of different overtones. In fact, the core of Part Four is the transformation of associations we have acquired in the first seventy minutes of the film, through unanticipated juxtapositions and superimpositions.

One of the major motifs of Part Three is a deep red shot of the full female figure, lying down and rising in one continuous movement. Brakhage triple-exposed this movement in the camera so that it appears on one layer of film. The woman seems to be rising out of herself in the composite. This shot had appeared proleptically in the Prelude and plays a significant role in the structure of Part Three. In its first appearance in Part Four, it reflects the rise of the hero, a sympathetic movement on the part of his female emanation; at the same time it introduces a very quick synecdochic narrative of lovemaking, conception, birth, and child-raising. The second figure in this sequence, a black-and-white image of bodies making love, also appeared in Part One, where it stood out as a rupture in the logic of the woodman’s drama. There I called attention to an unexplained image of childbirth. In Part Four the birth scene, like the brief shots of the redtinted woman, the genitalia, and the lovemaking, is presented very quickly and schematically, condensing the erotic and procreative cycle into a few seconds, but the visual echoes and metaphors make it perfectly clear what we are seeing. The occurrence of the shot of the Dog Star Man chopping wood early in this narrative renders that gesture a metaphor for lovemaking. Then a dynamic eruption of a solar corona, covered with emulsion scratches at the moment of the flame burst, symbolizes the orgasm. The whole movement from arousal, through copulation, labor, and birth to shots of breast-feeding and the dripping nipple which we recognize from Parts Two and Three takes less than a minute.

The narrative of the child continues after a lacuna in which the emphasis changes from sex and birth to topology. From an airplane we look down on mountain peaks, while in superimposition the camera zooms in on a house. The elaboration of this movement from a panorama of mountains down to the isolated house gives rise to the most dramatic play of depth and flatness in the entire film.

Originally the topological section of the film had been shot for a separate work, which like Meat Jewel was integrated into Dog Star Man and never completed in itself. This time another poet, Robert Kelly, had inspired Brakhage to make a landscape film by his use of the neologism “landshape.” Its amalgamation into Part Four is yet another instance of Brakhage’s proclaimed willingness to allow his film to develop as he edits it.

During the zooming movements on the house, flames appear in brief flashes, superimposed. Their locus becomes fixed in the family hearth as the virtual line from mountain to house extends inside, where we see the child, now several months old, crawling before a fireplace.

The crawling baby continues the haptic exploration of space initiated in the cradle of Part Two, while in superimposition the theme of the mountain develops. A third element in the combination, the protagonist on the mountain, once again compared to the baby as he feels his way around, sets up a metaphorical transformation: the fire before the baby evokes the corona of the sun, which in turn introduces a shot of the Dog Star Man looking up to the sun. He seems once again defeated, overpowered by the natural. He puts down his axe, and amid flashes of branches, the baby, flames, the corona, and white leader, he falls backward in slow motion down the mountain.

Stan Brakhage’s Dog Star Man: Part Two: collage of the infant’s scream.

Again the film-maker introduces the triple exposure in red of the settling and rising female nude, now in ironic analogy to the falling hero. Then a sunset announces the time of the fall.

At this point the film tantalizes us with a premature movement toward a conclusion. The images dissolve in whiteness. But after a long pause they reappear, now in winter with the bruised and stunned hero on his knees in pain and groping through the snowy forest. As night comes on and stars begin to move quickly across the sky, the summer mid-day images of the titan chopping the tree suddenly return and take over the film until its end. As he chops there is a brief transition to negative, superimposed over moving stars, which in the film-maker’s synopsis is the crucial moment of the conclusion. Within the rhythm of the film the negative image seems more a contingency than a true apotheosis, for the chopping continues after it in color. Intercut and superimposed with the regular gestures of the woodman appear splice marks, flares of film stock, and sprocket holes. In its final manifestation this often repeated image becomes a metaphor for the film-cutter. With the establishment of this connection the film evaporates in flares and leader.

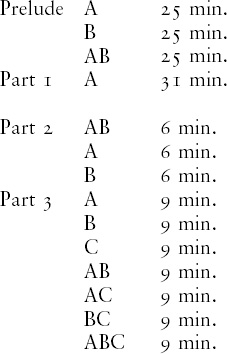

In The Art of Vision, Brakhage presents all the layers of film which went into the making of Dog Star Man, individually and in superimposed combinations. The following schema shows the order of the film. The layers of a given section are identified by letters, so that, for instance, first the A layer of Prelude is seen, then the B layer, then the two together or the actual Prelude as it appears in Dog Star Man. Thus all of the shorter film is enclosed within the longer. In outline the form is:

(Part One is the only section without superimposition.)

Originally Brakhage thought he would call this version The Complete Dog Star Man, but he changed his mind after showing it to Robert Kelly, before it had had a public presentation. Brakhage described his decision to alter the title in an unpublished interview with the author:

Really when I had the sense of being finished with this work was when the four and one-half hour work got a title separate from the seventy-five minute Dog Star Man composite. That happened when I visited the Kellys. We looked at all that material in that order I had given it. The morning after we had seen the whole thing, Kelly said at breakfast: “It seems to me you ought to read a life of Johann Sebastian Bach.” We took another couple of sips of coffee, and I thought, “Un-humm, well, that would be a good thing to do.” Then suddenly he came out with: “Well, to get that sense of form whereby a whole work can exist in the center of another work, or spiral out into pieces in another work, as in Baroque music, and that second arrangement be another piece entirely.” I said: “Well, you mean like—but that isn’t exactly what happens in The Art of the Fugue, but something like that.” Suddenly he came out with: “Why don’t you call it The Art of Vision?” Immediately that seemed to me a completely perfect thing to do. 11

He removed all the intermediary titles which announce the distinct sections of Dog Star Man. Two things immediately apparent from even a glance at the schema are that the present order elongates both the gradual concretion of the Prelude and the slow dissolution of Part Four, and that proportions of duration are radically altered. Aside from the obvious factor of duration, the longer version distinguishes itself by forcing an analytic procedure upon the viewer and by establishing a new sense of suspense in the combination or breakdown of superimpositions. Since the Prelude begins with its single layers, its colors are more vivid, not being cancelled out by the superimposition layer; its montage is more dynamic, without the elisions; and the visual pauses of black or white leader are more prominent. Since no title indicates the end of roll A and the beginning of B, only an experienced viewer can identify the transition. To a first viewer it would seem one continuous passage until the superimposition appears, but he would be aware of a formal and imagistic echoing of the first half hour of the film in the second. The eye, now familiar with the images in isolation, can discern the metaphors more surely and rapidly when in the third reel they arise through superimposition.

The breakdown of Part Two, unlike Prelude, decreates; in other words, the baby is divided from what he sees, suggesting that the object of the child’s vision is the chaotic imagery of the opening hour and a half. The severing of the two layers, with the object of vision first, and the child later, intensifies the textural analogies between the flashing rock, the skin of the nipple, the internal organs, and the trees.

In The Art of Vision the yellow nude at the end of the second roll of Part Two smoothes the transition to the colored female nudes that begin Part Three, which gradually builds up its layers. By itself, the C roll of heartbeats and hand-painting has an extraordinary beauty which the superimpositions diminish. In creating this image Brakhage was again deliberately trying to revitalize an outworn topos, the use of the heart as a symbol for love. In The Dead he had attempted the same kind of redemption of gravestones and the river as icons of death. The physical reality of the heart and its use as an orgasmic rhythm desentimentalize the symbol and make its use in this section potent. Finally, the extreme repetition of the layers of carnal images becomes itself an erotic metaphor.

Since Part Four was edited fugally with similar or identical images at significant points on all four layers, there can be no mistaking when one roll ends and the next begins. They all dissolve into flares, splices, and stars and begin again with the rising of the Dog Star Man. The form of the whole series reflects the dissolution within each of the variations as they reach their end. Watching the final hour and a half of variations on Part Four, one is impressed by the idea of a cyclical order, which is immanent in Dog Star Man as a whole. In the insistent repetition of structures during these fourteen sequences, the cycle becomes a major concept.

Dog Star Man and The Art of Vision were made at the height of the mythopoeic phase of American avant-garde cinema. Contemporary with their conception and presentation were Anger’s Scorpio Rising, Markopoulos’s Twice a Man, and Harry Smith’s Heaven and Earth Magic, which I shall discuss in the next chapter. In Brakhage’s film, perhaps more intensely than anywhere else, the strains of Romantic and post-Romantic poetry in American art converge with the aesthetics of Abstract Expressionism. The continuities and overlapping of artistic traditions make it difficult to pinpoint the specific vectors involved in the fusion of energies that went to make up American avant-garde cinema between 1943 and 1970, but some points can be made.

The influx of masters of European modernism into America at the time of the Second World War was a catalyst for significant developments in both film and painting.12 Yet those developments were not divorced from a native tradition, itself fed by European Romanticism, that can be seen in the poetry of Emerson, Whitman, Dickinson, Pound, Stevens, Crane, Williams, and Zukofsky. What we see today as the unified aesthetic of Abstract Expressionism was earlier a series of fiercely debated questions about form, procedure, and meaning. Although Maya Deren, for example, disassociates herself from the nonobjective painters of the 1940s and attacks them in her Anagram, her polemic is infused with a rhetoric they shared, and one sees in her last film, The Very Eye of Night, a drift toward late Cubist space—a loss of depth, the breakdown of horizontal and vertical centrality (in this particular case through the rejection of gravitational coordinates), and the affirmation of the screen’s surface, accompanied by an abstraction of the narrative tension which myth had given her earlier work. The visual texture and the structural principles of Sidney Peterson’s cinema were pointing in the same direction when he turned away from the medium.

Markopoulos and Anger, more secure in their Romantic conventions, resisted both plastic and structural transformations until the very end of the sixties; Broughton strenuously resisted them. It was Brakhage, of all the major American avant-garde film-makers, who first embraced the formal directives and verbal aesthetics of Abstract Expressionism.13 With his flying camera and fast cutting, and by covering the surface of the celluloid with paint and scratches, Brakhage drove the cinematic image into the space of Abstract Expressionism and relegated the conventional depth of focus to a function of the artistic will, as if to say “the deep axis will appear only when I find it necessary.”

The language of revelation and of process which I have excerpted repeatedly from the film-maker’s writings and speech recalls the statements of several painters. Jackson Pollock’s statement on his process coincides with Brakhage’s sense of artistic possession which recurs throughout Metaphors on Vision. Pollock wrote:

When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It is only after a sort of “get acquainted” period that I see what I have been about. I have no fears about making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own. I try to let it come through.14

The connection between myth and Abstract Expressionism was not a simple matter to the artists involved. Mark Rothko said:

Abstract Expressionist play of positive and negative space: the filed-out image in Stan Brakhage’s Dog Star Man: Part Three.

If our titles recall the known myths of antiquity, we have used them again because they are the eternal symbols upon which we must fall back to express basic psychological ideas. They are the symbols of man’s primitive fears and motivations, no matter in which land or what time, changing only in detail but never in substance, be they Greek, Aztec, Icelandic, or Egyptian. And modern psychology finds them still persisting in our dreams, our vernacular, and our art, for all the changes in the outward conditions of life.

Our presentation of these myths, however, must be in our own terms, which are at once more primitive and more modern than the myths themselves—more primitive because we seek the primeval and atavistic roots of the idea rather than the classical version; more modern than the myths themselves because we must redescribe their implications through our own experience.15

But Barnett Newman took a contrary position:

We are reasserting man’s natural desire for the exalted, for a concern with our relationship to the absolute emotions. We do not need the obsolete props of an outmoded and antiquated legend. We are creating images whose reality is self-evident and which are devoid of the props and crutches that evoke associations with outmoded images, both sublime and beautiful. We are freeing ourselves of the impediments of memory, association, nostalgia, legend, myth, or what have you.16

Ironically, Rothko gave formalistic titles to his canvases while Newman continued to label them with Biblical names (“Abraham,” “Jericho”), religious associations (“The Stations of the Cross”), and Greek mythology (“Prometheus Bound”). Pollock vacillated between formalistic and mythic titles (“Lucifer,” “Moon Woman Cuts the Circle,” and “Cut-Out,” “Number One”) just as his art had its formalistic and psychological poles.

Brakhage is too eager a dialectician to have ignored this debate, both in its public and its interior forms. In “Margin Alien” he quotes toughminded Clyfford Still (who persists in labeling his paintings by their dates of completion, e.g., “Painting, 1948-D”):

We are committed to an unqualified act, not illustrating outworn myths or contemporary alibis. One must accept total responsibility for what he executes. And the measure of his greatness will be the depth of his insight and courage in realizing his own vision. Demands for communication are presumptuous and irrelevant.17

Even while he was making Dog Star Man Brakhage had inherited the Abstract Expressionist’s uneasiness with mythical referents and structures, as the inclusion of this quotation shows. Yet for Brakhage, dialectical uneasiness is a source of strength. Immediately following the references to Still and Michael McClure, another antimythologist, Brakhage prints in corresponding columns excepts from a statement on poetics by Charles Olson and bits of anti-aesthetics from John Cage. And throughout his writing Brakhage argues with himself and against the very need to write: “It is only as of use as useless.”

The conception of Songs was a dramatic event in Brakhage’s life. He had come to New York where he showed the completed Parts Two and Three of Dog Star Man with a vague idea of joining the New American Cinema Exposition then traveling in Europe. While in the city his 16mm equipment was stolen from his car. He collected enough money to get himself and his family back to Colorado, but he did not have funds for new equipment. With the twenty-five dollars paid by his limited insurance on the stolen equipment, he discovered he could buy an 8mm camera and editing materials. He did so. At least three factors were involved in the switch to 8mm, beyond what Brakhage would call the “magical” coincidence of finding the inexpensive equipment when he went looking to replace what he had lost.

In the first place, he wanted to get away from the giant form of The Art of Vision which had occupied him for seven years. Then, there was a definite economic advantage in making 8mm films: materials and laboratory prices were much lower than for 16mm work, and one could not be tempted into costly printing work (mixing layers of film, fades, etc.) simply because no laboratory undertook to do that in 8mm. All superimposition, dissolving, and fading had to be done in the camera. Finally, Brakhage saw a polemical advantage in the switch. Not only would his example dignify and encourage younger film-makers who could afford to work only in 8mm, but he would be able to realize, on a limited scale, a dream he had had for years of selling copies of his films, rather than just renting them, to people for home viewing. Since the early 1960 she had been prophesying a breakthrough for the avant-garde film-maker when films would be available for purchase like books, records, and painting reproductions and could therefore be owned and screened many times and at pleasure.

In the beginning Brakhage had no idea that Songs would become a single, serial work. Even after making the first eight sections he resisted that idea. But by the spring of 1965, with ten Songs finished in a little more than a year, he began to speak of the totality of the work in progress: “I think there will be more Songs. I do definitely see that they relate to each other. That is, practically every Song has images in it that occur in some other Song, if not in two or three others. The more remarkable thing is that each Song is distinct from each other; that holds them together in a very crucial kind of ‘tension.’ “18 Within another year he was punning on the relation of a Song’s number in the series to its subject (XV Song Traits, 23rd Psalm Branch); soon after that he was wondering when they would end. They did conclude, with a dedication to the film-maker Jerome Hill, after thirty Songs, or punning again, American Thirties Song, in 1969.

Brakhage’s capsule descriptions, written for his own sales catalogue, describe with varying degrees of directness the subjects of the individual Songs.

SONGS

Go, little naked and impudent songs,

Go with a light foot!

(Or with two light feet, if it please you!)

Go and dance shamelessly!

Go with an impertinent frolic!

Greet the grave and the stodgy,

Salute them with your thumbs at your noses.

Ezra Pound, “Salutation the Second.”

SONG I (1964); 4 min. Color. A portrait of a beautiful woman.

SONGS II& III (1964); 7 min. Color. An envisionation of fire and a mind’s movement in remembering.

SONG IV (1964); 4 min. Color. A round-about three girls playing with a ball… hand-painted over photo image.

SONG V (1964); 7 min. Color. A child-birth song,… I think my best birth film yet.

SONGS VI & VII (1964); 7 min. Color. vi: A song of the painted veil—arrived at via moth-death. vii: A San Francisco song—portrait of the City of Brakhage dreams.

SONG VIII (1964); 4 min. Color. A sea creatures song—a seeing of ocean as creature.

SONG IX & X (1965); 10 min. Color. ix: a wedding song—of source and substance of marriage. x: a sitting around song.

SONG XI (1965); 6 min. Color. A black velvet film of fires, windows, insect life, and a lyre of rain scratches.

SONG XII (1965); 6 min. Black and white. Verticals and shadows—reflections caught in glass traps.

SONG XIII (1965); 6 min. Color. A travel song of scenes and horizontals.

SONG XIV (1965); 3 min. Color. A “closed-eye” vision song composed of molds, paints, and crystals.

XV SONG TRAITS (1965); 75 min. Color. A series of individual portraits of friends and family, all interrelated in what might be called a branch growing directly from the trunks of SONGS I-XIV. In order of appearance: Robert Kelly, Jane and our dog Durin, our boys Bearthm, and Rarc, daughter Crystal and the canary Cheep Donkey, Robert Creeley and Michael McClure, the rest of our girls Myrrena & Neowyn, Angelo diBenedetto, Rarc, Ed Dorn and his family, Myrrena, Neowyn, and Jonas Mekas (to whom the whole of the XVTH SONG is dedicated), as well as some few strangers, were the source of these TRAITS coming into being—my thanks to all… and to all who see them clearly.

SONG XIV (1965); 8 min. Color. A love song, a flowering of sex as in the mind’s eye, a joy.

SONGS XVII & XVIII (1965); 7 min. Color. Cathedral and movie house—the ritual memories of religion—and then (in song xviii) a portrait of a singular room in the imagination.

SONGS XIX & XX (1965); 8 min. Color. A dancing song of women’s rites, and then (song xx) the ritual of light making shape/shaping picture.

SONGS XII & XII (1966); 8 min. Color. Transformation-of-thesingular-image was the guiding aesthetic light in the making of these two works.

SONG XXI works its spell thru closed-eye-vision, whereas SONG XXII was inspired by approximates of “the dot-plane” or “grain field” of closed-eye-vision in textured “reality,” so to speak. You could say that XXI arises out of an inner- and XXII into an outer-reality. These two works are particularly exciting to me because I at last accomplished something in the making of them that I had written hopefully to Maya Deren about years ago: films which could be run forwards AND backwards with equal/integral authenticity—that is that the run from end to beginning would hold to the central concern of the film … rather than simply being some wind and/or unwinding of beginning-to-ending’s continuum. SONG XXII, additionally, can be run from its mid-point—the singular sun-star shape on water—in either direction to beginning or ending … thus film inherits the possibilities Gabrieli gave to music with his piece “My beginning is my ending and my ending is my beginning.”

SONG XXIII :23RD PSALAM BRANCH (1966-67); 100 min. Color.

Part I—A study of war, created in the imagination in the wake of newsreel death and destruction.… We had moved around a lot and we had settled down enough… so we got a TV. And that was something in the house that I could simply not photograph, simply could not deal with visually. It was pouring forth war guilt, primarily, into the household in a way that I wanted to relate to, if I was guilty, but I had feelings … of the qualities of guilt and I wanted to have it real for me and I wanted to deal with it.

And, I mean, it was happening on all the programs—on the ads as well as drama and even the comedies, and of course the news programs. And I had to deal with that. It finally became such a crisis that I knew I couldn’t deal directly with TV but perhaps I could make or find out why war was all that unreal to me….

Part II—A searching-into the “sources” of Part I, it is composed of the following sections: Peter Kubelka’s Vienna, My Vienna, A Tribute to Freud, Nietzsche’s Lamb, East Berlin, and Coda.

SONGS XXIV & XXV (1967); 10 min. Color. A naked boy and flute song and (xxv) a being about nature.

SONG XXVI (1967); 8 min. Color. A “conversation piece”—a viz-a-visual, inspired by the (e) motional properties of talk: drone, bird-like twitterings, statement terror, and bombast.

MY MOUNTAIN SONG XXVII (1968); 26 min. Color. A study of Arapahoe Peak in all the seasons of two years’ photography . . . the clouds and weathers that shape its place in landscape—much of the photography a-frame-at-a-time: Rivers (1968); 36 min. Color. A series of eight films intended to echo the themes of MY MOUNTAIN, SONG XXVII.

SONG XXVIII (1968); 4 min. Color. A song of scenes as texture.

SONG XXIX (1969); 4 min. Color. A portrait of the artist’s mother.

AMERICAN THIRTIES SONG (1969); 30 min. Color. This film, preceded by a portrait of the artist’s father, is a long ode to the drives and driving spirit of the nineteen-thirties and of some of the shapes and textures these energies created across the American landscape. This film is dedicated to Jerome Hill, whose image appears at the end of its “postlude.”19

The scope of Songs ranges from the immediate recording of the objects of a room by the film-maker sitting in a chaise-longue (Song X) to massive meditations on war in two long parts, the second of which has six subdivisions (23rd Psalm Branch). But even that most complex of the Songs contains moments and parts resembling the simplest. The persistence and diversity of the simple strategies define the elusive unity of the serial work. As far as Brakhage may go in forging a complex vision out of the reluctant materials of 8mm, he always returns to the immediate, the sketch, the familiar—whatever risks being overlooked. The peripety of the thirty Songs circumscribes Brakhage the lyricist and apocalyptic visionary while he seeks to discover the limits of his new tool, the 8mm camera and film surface.

Several of the Songs reconsider the questions, emotions, and situations of his earlier films. Song V, punning on the birth of his fifth child, brings to mind both Window Water Baby Moving and Thigh Line Lyre Triangular, without the drama of the first or the inwardness of the other.

In Song VI he looks again for an image of death while filming the last moments of a moth against the background of flowered linoleum. Without the possibility of solarization (as in The Dead) or collage (as in Mothlight), the film-maker must seek simpler means, and he develops a tension between the focus on the moth and the linoleum under him, visually incarnating Shelley’s description of the filter between eternal and human life as a “painted veil.”

In Song XVI he once again attempted to redeem a trite metaphor as he had previously done in The Dead and Part Three of Dog Star Man. Bracketed by shots of a misty landscape, the film compares flowers to sexual organs, and with its continual slow zooms on two layers of superimposition it evokes the rhythms of lovemaking. Often the erotic images are indistinct, but at the opening there are nipples, and then an erect penis is caressed. The film proceeds from the explicit to the suggestive. At the film’s climax an orange fan of coral replaces the flowers. Then the end comes quickly: buttocks superimposed with other pieces of coral and starfish amid flares of orange. The transformation of the flowers into coral provides the film’s finest moment; otherwise the flower imagery falls short of the film-maker’s redemptive aspiration for it.

The unity of Songs as a whole does not depend entirely on the sometimes reassuring, sometimes startling reuse of specific images from earlier Songs in later ones. Even though 8mm superimposition must be done in the camera, which denies the frame-to-frame precision possible in 16mm dual-track editing, Brakhage makes extensive use of it. In numerous Songs there are isolated superimposed images cut into the texture of the film, but in the following films, superimposition is a major force shaping the totality: I, II, V, VII, VIII, XII; “Jane and the Boys,” “Angelo,” “Myrrena,” and “Neowyn” from XV Song Traits; XVI, XVII, XXII; and “Nietzsche’s Lamb” and the “Coda” from the 23rd Psalm Branch.

Painting, scratching, and the laying of dots over the image appear periodically in the series, despite the immense difficulty of working on the surface of a film strip that has only one-fourth the area of 16mm. Songs IV, XIV, XXII, and the first part and “Nietzsche’s Lamb” from the 23rd Psalm Branch depend upon these techniques. Close in texture to the handpainted Songs are the nonobjective works (XI, XX, XXI), exhibiting for the most part patterns of pure light.

Despite the extreme mobility of the 8mm camera, the Songs depend less on camera movement than the earlier lyrical films. Brakhage’s fight with the natural world seems at first to have quieted and his inwardness diminished. With couplings such as XXI and XXII and “Rivers” following Song XXVII: My Mountain, the opposition of consciousness to the natural world reaffirms itself; once again the accent is upon the visionary seer, not what he sees. In the light of the whole series, the opposition of early couplets such as II and III grows clearer. Again, the clues lie in the filmmaker’s note: “An envisionation of fire and a mind’s movement in remembering.”

Song II shows air distorted by heat, as if just above a burning fire, and the sinking sun intercut with rapids of water. It invokes the concept of fire without showing a flame. In III, on the other hand, the same images of rushing water form a rhythmic montage, alternating directions, into which undistinguished shots of a street are injected and lost. Bits of an exceptionally grainy green leader, which at first divide the movements of water, eventually dominate the film. The displacement of emphasis reduces the water from presence to a metaphor for the eccentric movements of the grain. In the unpublished interview I have quoted before, Brakhage describes the making of this film:

We were listening to Brahms’ Third Symphony and became very tortured by the incredible beauty of its seeming to build up various kinds of tension and never breaking through any of them. I said, “That is a mind process: the way in which the mind gets hung up magnificently.” It was such a disturbing moment that when we finished listening to it we were so excited and at the same time frustrated that Jane rushed out into the night to take a walk and I immediately picked up some green leader which had been baked in the sun … that seemed to stand for some basic impulse of mine. The question was what could I drop into that space? Water, of course, was there. Water shots relate to the grain.

I struggled to get something else in there by dropping in a photographic shot. I borrowed what had come with the little 8mm viewer I bought at this time. It was shot by the man who owned the camera store; some shots out of his window of a scene in Boulder. It was quite photographic; quite like a picture postcard with moving cars. It became possible by editing this green leader very carefully, so that it built a certain tension, to drop this scene into it via the water shots, which then could be drowned by water in another scene. That was a breakthrough which could make the leader relate to water and then fall back into being just the basic strata of mind movement.20

Brakhage never made any changes in already finished Songs to bring them into a more explicit relationship with later ones. Some of the oppositions are obviously deliberate, such as II and III, XXI and XXII, and others less conscious. But there is no overall antithesis, even of the most eccentric order. Instead of a center of gravity, Songs has a turning point in the 23rd Psalm Branch, the longest and most intricate of the works. Here the repudiation of the physical world in favor of the poetic consciousness exceeds Brakhage’s previous extremes, but two films later, in Song XXV, the vehemence is qualified and calmed.

Numerically, although not temporally, in the center of the thirty films are the XV Song Traits. The form of the portrait radiates through the Songs, including I, XXIV, and XXIX with fragmentary portraits worked into the first part of the 23rd Psalm Branch and the end of the American Thirties Song. Superimposition and synecdoche are the predominant tropes of the film-maker’s portraiture. Song I shows several full figures of his wife Jane in a striped robe reading and making gestures, whose individuality are emphasized by slightly fast-motion recording. In superimposition, passing boulders can be seen from a car, and toward the end of the film there are successive entrances of someone through a doorway. Brakhage defines “Robert Kelly” through close-ups of his hands, pointing and cutting cheese, with occasional reference to his face, but not full-figure. Again in “Jane and Durin,” he gives us parts of the event without the wide view; the image will rest on his wife’s ankle or on the dog’s stomach as she scratches him. Only in the final and dedicatory portrait of Jonas Mekas does he combine close-up gestures with characteristic movements of the whole body without recourse to superimposition.

Within the limits of the film-maker’s conception of portraiture, the range of his formal invention is wide. That conception comes close to an older desire which he shared with Maya Deren and about which he corresponded with her—that of creating a cinematic haiku form. On the one hand, the simplified superimposition of 8mm may be compared to the haiku’s juxtaposition of two isolated images. On the other hand, Brakhage also employs a two-part form in some of the simpler Songs. The synecdoches of Kelly, for instance, precede the appearance, fragmentation, and reappearance of a moving geometrical form resembling the diagram of election orbits around a nucleus or planets around a sun, filmed off a television monitor. “The Dorns” contrasts snapshots of the poet Ed Dorn and his family with color-filmed images, as if the film-maker was looking at the photographs and remembering the moving scene.

Synecdoche is crucial to all of Brakhage’s cinema, but in Song XVIII it attains a prominence comparable to the portraits. The “portrait of a singular room in the imagination” consists of shadows, illuminated corners, bits of wall decoration, surfaces abstracted beyond identification, and a closing door. Critic Guy Davenport informs us that we are in a dentist’s office in this film.21

The portrait of “Crystal,” by way of contrast to the simple structures so far described, uses parallel montage as intricately as the most elaborate of the Songs except the 23rd Psalm Branch. Above all it recalls the play of diverse elements in the epithalamion Song IX. A very washed-out, dim shot of young Crystal Brakhage crying repeats itself amid images of snow outside a window, a canary in a cage, people and reflections at an airport (reminiscent of Song XII without quoting from it), children’s drawings, horses in a blizzard, and changes of light intensity through a window. The movements of the camera and the elisions and collisions of the editing return to the visual rhetoric of Anticipation of the Night. The elements of the portrait combine to describe the anxiety of a child away from home, and the repeated emphasis on the cage and even more on looking out of the windows of the house raises the metaphor of the self as the center of both the house and the cage.

In Song IX similar camera movements and montage seem more spectacular because the images they fuse together are more disparate. A rhinoceros pacing back and forth in a cage with a patch of sunlight on his hide establishes the initial tempo, into which are cut shots of an outdoor wedding by moonlight, two naked children in sex play, a door opening on an empty room, and later a moving shot out of the same room with a young man silhouetted in it. The jittery dance of the moon over the wedding party makes specific the allusion to Anticipation of the Night which is felt in the construction. There also appears a brief quotation of a window by the sea taken from the beginning of Song VII. For Davenport, whose insights on the Songs are always valuable, the collision of the wedding party with the rhinoceros and the “nonchalantly and impudently naked” children make the film “a comic masterpiece…. Brakhage’s sense of humor is the most difficult of his strategies,” he tells us. “In an age of largely feminine humor, he remains doggedly masculine in his laughter.” 22

His point is well taken; for of the erotic Songs this is the only piece of ribaldry. In place of Song XVI which Davenport admires, I would propose Song XIX as the high point of sexual energy in the series. The film centers upon slow and fast motion alternations of a woman and a girl dancing. One appears to be the film-maker’s wife, but it is difficult to be certain of identifications in the silhouette effect that their moving bodies create in the dim foreground with a bright window behind. The other seems in her late adolescence. At first the camera picks out from their slow movements slow jumps of the feet or flights of arms. Sometimes only a corner or edge of the now blackened screen has a flickering image, a rhythmic synecdoche of the dance. As they accelerate to a humping motion, or so the camera makes them seem, the shadows merge their jagged edges in an erotic fusion. Through an open door, bright leaves can be seen blown by the wind and speeded up by the camera until their shimmering recalls the dancers. Another, younger, girl watches from the doorway as the blending of bodies becomes frantic, until the image burns out in flares.

With the return of a picture we see an altogether different couple, a man and a woman standing outside with their dog. The zoom slowly pulls back from this black-and-white image, returning inside by montage to the fast dance and dim colors several times. The zoom continues to the end of the film, revealing a house, then its grounds, a whole village, and finally an arid landscape of hills in which the village is situated. Night is falling. In a diminuendo of erotic tension the returns to the dance now show the smaller girl taking part accompanied by playful leaps of her dog.

Brakhage has said that this was filmed during a visit to Robert Creeley’s family in New Mexico. Presumably Creeley and his wife were the figures before the house, and his two daughters were dancing with Jane Brakhage. Creeley had already appeared in the most exceptional of the portraits. As he sits and rises from a chair, he changes from positive to negative, an intensely subjective image with a presentiment of aging. This portrait and the following staccato pixilation of McClure putting on a beast’s head were originally shot and edited in 16mm and reduced, to be included in XV Song Traits as well as released in 16mm as Two: Creeley/McClure. The solarization of the Creeley portrait would be impossible in 8mm where there is neither negative film nor laboratory superimposition.

The furthest that Brakhage came in extending the language of 8mm cinema was his editing of the 23rd Psalm Branch. Here he managed to create extended passages of dynamic montage out of two-frame (onetwelfth of a second) elements. He solved the problem of cluttering the screen with hundreds of splicing marks by introducing two frames of black leader between every shot, causing a rapid winking effect in the projection of the film but hiding the splices. He also succeeded in applying several sizes and varieties of ink dots to the surface of the 8mm image; at times hundreds seem to be clustered in the tiny frames.

The phenomenal and painstaking craftsmanship of this film reflects the intensity of the obsession with which its theme grasped his mind. In 1966, out of confusion about the Vietnam war and the American reaction to it, with which he had to deal in the question periods following his lectures on various campuses, Brakhage began to meditate on the nature of war. He amassed a collection of war documentaries and diligently studied newsreels and political speeches on television to the point of speculating on the significance of recurring clusters and shapes of the dots on the television screen; he read memoirs and battle descriptions, Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and he claimed to read Tacitus instead of the daily newspaper at breakfast because the intrigues were the same and better written in the first century historian’s version. The fruit of his studies and thoughts was the longest and most important of the Songs. A tour of lectures, in which he tried to express what could not be contained in the film was so confused and self-tortured in style that it approached madness.

If any of the earlier Songs seemed to assert the priority of nature over imagination, that impression has no place in the 23rd Psalm Branch; it is an apocalypse of the imagination. The consciousness of the film-maker moves between his idea of home and the self and his vision of war. A very fast pan of a passing landscape, as if shot from a car on a highway, stops short continually with the flashing interjection of dead bodies from stock black-and-white footage and flickerings of solid colors. In the prolongation of this effect the short images of death are sometimes painted over.

The first release from this insistent prologue comes as the words “Take back Beethoven’s 9th, then, he said” are scratched in black leader.23 They are the first of several quotations in the film. Another continuous pan follows, shot like the first but showing a deep passing land- and townscape rather than a moving flat blur. Into this lateral movement he first cuts a series of explosions, then explosions mixed with guns firing, the atomic bomb, a flood, cannon exploding, water leaping over a dam, tactical bombs, and burning buildings. At times the montage of horrors pursues its own split-second dynamic as if forgetting to relocate itself in the passing American landscape.

In his lectures at the time, Brakhage maintained a desperate fatalism. He spoke of war as a “natural disaster,” assigning it an inevitable role like that of tornadoes or earthquakes. At times his audiences, and perhaps he himself, took this postulate to be a reconciliation with the fact of war, when within the film it was another, more vehement attack on nature.

A color flicker transfers us to a second text, a letter being written by the film-maker as he sits bare-chested in the sun. The speed of the panning makes it difficult to read. “Dear Jane,” it begins, “The checker boards and zig-zags of man.” On the next line we can only catch the crucial word “Nature.” Turning from the letter, the camera shows us stones, fast movements over the ground, and flashes of a blue-tinted sun until a multicolored, hand-painted passage intrudes. It precedes a fast montage of images of the home, including visual quotations of the nude children from the “Neowyn” portrait and sledge riding from “Myrrena and Neowyn.” The pace of the editing relaxes with shots of laundry on a wash line, a donkey, the sky. Airplane wings introduce a return to the letter, and the subsequent quick cutting of wings, clouds, and aerial views of the ground illustrate the expressions “zig-zags” and “checker boards.”

After another color flicker and a passage of hand-painting, a third quotation, in the form of an open book of poetry, emerges. It is the beginning of the eleventh section of Louis Zukofsky’s A:

River, that must turn full after I stop dying

Song, my song, raise grief to music

Light as my loves’ thought, the few sick

So sick of wrangling: thus weeping

Sounds of light, stay in her keeping

And my son’s face—this much for honor.

The second line is most readable in the camera’s panning. “Song, my song, raise grief to music” defines the aspiration of the film and the cry of the film-maker. Another burst of explosions and bombs brackets a visual repetition of the poem.

Fast animation of children’s drawings, also warlike, introduces a flickering alternation between them and the film-maker’s face; and then the face alone flickers amid bits of blackness. The same fragmenting rhythm presents two warriors fighting in a print of a Hellenic vase, which disappears in red flares. Then, after a pause of blackness, the camera draws back from the face of the poet Zukofsky. His name on his book identifies him for those who do not recognize his rarely photographed face. Another zoom shows, dimly, his wife Celia. We see the poet only once more; that is after an exposition of colored frames mixed with the wrecks of buildings. But this time the movement away from his face leads to a series of Jews in concentration camps, as the film-maker considers what might have been the poet’s fate had he lived in Europe thirty years before.