NOT ALL AVANT-GARDE film-making of the late 1950s utilized the trance form and psycho-drama. The graphic cinema offered a vital alternative to the subjective. This polarity (and the potential for its convergence) extends back to the origins of the avant-garde film in Europe in the 1920s. Through the examples of Un Chien Andalou, Le Sang d’un Poète, and Entr’Acte, a continuity has been suggested between the Surrealist and Dada cinema and the works of Maya Deren and Sidney Peterson. Another wing of the Dadaist cinema fused with filmic Cubism and Neoplasticism to produce films of equally major significance. In the 1920s the spectrum extending from Surrealism to Cubism in the cinema was continuous. But with the renaissance of independent film-making in America during and just after the Second World War, graphic and subjective film-making ideologically diverged and remained apart until their slow reconciliation in the early 1960s.

Hans Richter’s Rhythmus 21 (1921), Viking Eggeling’s Symphonie Diagonale (1921), Marcel Duchamp’s Anémic Cinéma (1927), and Fernand Léger’s Ballet Mécanique (1924) constitute the central works of the initial graphic cinema, and they span the scope of its variations.

Richter, who had been a painter and scroll-maker, took the primal conditions of black and white and the rectangular shape of the screen as the essential elements of his film. In sweeping movements which begin in the center of the screen and move out horizontally or vertically, the flat black space becomes white or vice versa. Within this matrix of fluctuating negative and positive space, white, gray, and black squares emerge from and recede into an illusory depth of the screen in a rhythmic pattern that grows increasingly more intricate until its sudden and short reversal to the elements of the black-and-white screen at the very end of the film.

Eggeling worked with Richter, and like him the urge to make films came from a desire to extend his work on scrolls into time. In his film Symphonie Diagonale, figures move along alternative diagonal lines crossing the screen from upper left to lower right and from upper right to lower left. At the same time they seem to move in depth from the surface of the screen to an imaginary receding point at its center, as Richter’s squares had, and back again. Finally, Eggeling’s shapes evolve in straight and elaborately curved lines while they pursue their diagonal and emerging-receding movements. The musicality of Symphonie Diagonale comes from its exhaustive use of reciprocal movements. An elaboration along one diagonal axis is mirrored immediately along the other; the growth at one end of a figure is matched by its disunion at another end; a movement into the screen precedes one out of it.

In Anémic Cinéma, Duchamp alternates head-on views of his illusionproducing roto-reliefs with similarly turned discs of words, elaborate French puns printed spirally, creating a fluctuation of illusory depth within a very narrow spectrum (from the slightly convex or slightly concave illusions) to the flat readings. In this, his only film, Duchamp typically crystallized the significance of the graphic film. By virtue of its inheritance from still photography, the representation of space in depth comes naturally to the cinema, and the first films exploited it gloriously. The graphic filmmaker deliberately rejected the illusion of depth built into the camera’s lenses.1 He set out to re-establish virtual depth by manipulating the scale of flat plastic shapes (Richter and Eggeling), through the presenting and unmasking of simple optical illusions (Duchamp), and lastly with the obliteration of accustomed depth while retaining the traditional photographic images (as we shall see in various strategies of Léger).

The Surrealist cinema largely disappeared after Buñuel’s L’Age d’Or (1930) to re-emerge thirteen years later in America, essentially transformed. The graphic cinema, on the other hand, continued its evolution with diminished force throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The coming of sound to film inspired several attempts to visualize music through cinematic abstractions and to synchronize visual rhythms to music.

The central figure in the transition from the European to the American graphic film was Len Lye.2 A New Zealander, Lye became intrigued with the kinetic possibilities of art when he was an adolescent, as he elaborates in an interview in Film Culture 29:

I had read that Constable had tried to paint clouds in motion and the Dadaists were experimenting with motion painting also. I had a paper route at that time, so I used to get up early and go off for a walk and try to sort out things about art. Then it hit me as I was looking at those darn sunrises, lit up clouds, why try to simulate motion in paintings of clouds or in afterimage effects? Why not just do something that literally made movement?

Early in the 1920s he went to Australia to learn cartoon animation, but he did not make his first film until he moved to London in 1928. There he made Tusalava (Samoan for “things go full circle”), a black-andwhite film combining his fascination with movement with the imagery of South Pacific primitive art, a life-long interest. Yet cartoon animation has played a very small part in Lye’s most important contributions to the graphic cinema. In fact, in the act of rejecting cartoon procedures, with which films such as Richter’s and Eggeling’s had been made, he became the first film-maker to paint directly on top of film stock, thus shortcutting the photographic process. Although Colour Box (1935) was the first result of this direct method, Lye’s experiments in hand-painting film go back to Australia and the mid-1920s.

The direct application of paint to the surface of film transformed the dynamics of the graphic film. Color could be rendered more vivid than it could by the photographic process; the different kinds and densities of paint opened a range of texture hitherto ignored; and above all the problems of shape, scale, and the illusions of perspective which the early graphic film-makers inherited from the painterly and photographic traditions could be bracketed by an imagery that remained flat on the plane of the screen and avoided geometrical contour.

In Colour Box, a wavy, vertical line multiplies itself and interacts with circles and fields of dots against a background washed with paint. Although Lye avoids all indications of screen depth by having no movement into or out of the vanishing point, the lines and circles seem to move in front of the unshaped background paint, and both seem recessed slightly when stenciled letters, telling us to use parcel post, appear near the end and affirm a plane even closer to the literal screen than the painted plane. This use of block lettering recalls the similar employment of stencils in analytical cubism.

Apparently Lye was more interested in expanding a vocabulary of dynamic visual forms than in exploring the implications and possibilities of a cinema without photography; for in his next film, Kaleidoscope (1936) hand-painting becomes less important than stenciling. Dots, complex patterns, circles, lines, and arabesques crisscross the screen in muted colors. Again the shapes and colors hug the surface of the screen with no indications of depth other than the shallow superimposition of some forms as they pass over one another.

Lye never completely abandoned working with the raw surface of unphotographed film, but his evolution as a film-maker did not occur along the lines initiated by this startling invention. In Rainbow Dance and Trade Tattoo (both 1936), he combined some of his surface techniques with photographed images of actuality. Although his reputation has been sustained by the invention of direct painting on film, Lye deserves equal credit as one of the great masters of montage. His specialty has been the jump-cut, an elliptical condensation of action achieved by eliminating middle shots so that the figure on the screen seems to jump forward along a prescribed course of action.

Along with the combination of elliptically edited scenes of elementary actions and surface lines, dots, and shapes, Lye began to develop techniques of color separation. Through an intricate process of masking and combining negative and positive images in the printing laboratory, Lye could make one figure in a photographed scene assume one pure color and another figure in that same originally black-and-white shot take on a different color. In doing so he achieved a strength of color his first films lacked, but only unhampered paint on film could create the lost textural range of the surface.

In his later works Lye moved away from both color and the synthesis of techniques. Rhythm (1953) shows the assembly of a Ford in one minute of hundreds of jump-cuts. The film is black-and-white without any abstract surface texture save white holes punched out of the opening and ending shots of the exterior of the Ford plant. Having created a film purely exploiting the jump-cut, he made another working only with the surface of unphotographed film. This time he scratched ideographic lines on black film stock. Free Radicals (1958) reduces and distills the dynamics of the hand-made film to a primitive kinetic dance of white lines and angles. The jaggedness of these meticulously executed scratches in an indexical evocation of the concentrated energy required to etch them onto film. The film-maker has described the quality of the movement as “spastic.” Of his working method he has said:

If I couldn’t complete the etched line by forcing the needle to complete the design on the film, then the continuity of a dozen or so designs which preceded it would be lost. So, I wriggled my whole body to get a compressed feeling into my shoulders—trying to get a pent-up feeling of inexorable precision into the fingers of both hands which grasped the needle and, with a sudden jump, pulled the needle through the celluloid and completed my design.3

When in the early 1940s Harry Smith made his first hand-painted films, he was unaware that the concept was not original with him; such is his claim, which the author believes. To the historian of cinema it would make little difference if Smith acted by invention or imitation, for his reputation is not bound to any proof of priority. The hand-painted films with which he began his career as a film-maker are the most remarkable ever achieved in that technique; and his subsequent films, both animated and photographed from actuality, sustain his stature as one of the central filmmakers of the avant-garde tradition.

With characteristic self-irony and hermetic allusions, he composed the following notes on his work for the catalogue of the Film-Makers’ Cooperative:

My cinematic excreta is of four varieties:—batiked abstractions made directly on film between 1939 and 1946; optically printed non-objective studies composed around 1950; semi-realistic animated collages made as part of my alchemical labors of 1957 to 1962; and chronologically superimposed photographs of actualities formed since the latter year. All these works have been organized in specific patterns derived from the interlocking beats of the respiration, the heart and the EEG Alpha component and should be observed together in order, or not at all, for they are valuable works, works that will live forever—they made me gray.

no. 1: Hand-drawn animation of dirty shapes—the history of the geologic period reduced to orgasm length. (Approx. 5 min.)

no. 2: Batiked animation, etc. etc. The action takes place either inside the sun or in Zurich, Switzerland. (Approx. 10 min.)

no. 3: Batiked animation made of dead squares, the most complex hand-drawn film imaginable. (Approx. 10 min.)

no. 4: Black-and-white abstractions of dots and grillworks made in a single night. (Approx. 6 min.)

no. 5: Color abstraction. Homage to Oscar Fischinger—a sequel to No. 4. (Approx. 6 min.)

no. 6: Three-dimensional, optically printed, abstraction using glasses the color of Heaven & Earth. (Approx. 20 min.)

no. 7: Optically printed Pythagoreanism in four movements supported on squares, circles, grillworks and triangles with an interlude concerning an experiment. (Approx. 15 min.)

no. 8: Black-and-white collage made up of clippings from 19th Century ladies’ wear catalogues and elocution books. The cat, the dog, the statue and the Hygrometer appear here for the first time. (Approx. 5 min.)

no. 9: Color collage of biology books and 19th Century temperance posters. An attempt to reconstruct Capt. Cook’s Tapa collection. (Approx. 10 min.)

no. 10: An exposition of Buddhism and the Kaballa in the form of a collage. The final scene shows Aquatic mushrooms (not in No. 11) growing on the moon while the Hero and Heroine row by on a cerebrum. (Approx. 10 min.)

no. 11: A commentary on and exposition of No. 10 synchronized to Monk’s “Mysterioso.” A famous film—available sooner or later from Cinema 16. (Approx. 4 min.)

no. 12: A much expanded version of No. 8. The first part depicts the heroine’s toothache consequent to the loss of a very valuable watermelon, her dentistry and transportation to heaven. Next follows an elaborate exposition of the heavenly land in terms of Israel, Montreal and the second part depicts the return to earth from being eaten by Max Muller on the day Edward the Seventh dedicated the Great Sewer of London. (Approx. 50 min.)

no. 13: Fragments and tests of Shamanism in the guise of a children’s story. This film, made with van Wolf, is perhaps the most expensive animated film ever made—the cost running well over ten thousand dollars a minute—wide screen, stereophonic sound of the ballet music from Faust. Production was halted when a major investor (H. P.) was found dead under embarrassing conditions. (Approx. 3 hours).

no. 14: Superimposed photography of Mr. Fleischman’s butcher shop in New York, and the Kiowa around Anadarko, Oklahoma—with Cognate Material. The strip is dark at the beginning and end, light in the middle, and is structured 122333221. I honor it the most of my films, otherwise a not very popular one before 1972. If the exciter lamp blows, play Bert Brecht’s “Mahagonny.” (Approx. 25 min.)

For those who are interested in such things: Nos. 1 to 5 were made under pot; No. 6 with schmeck (it made the sun shine) and ups; No. 7 with cocaine and ups; Nos. 8 to 12 with almost anything, but mainly deprivation, and 13 with green pills from Max Jacobson, pink pills from Tim Leary, and vodka; No. 14 with vodka and Italian Swiss white port.4

The continuity of Harry Smith’s cinema is remarkable, all the more so because of its variety. The shifts in technique and the swerves in intention of each new film seem grounded in the principles of the previous film. After the initial attempt at a freely drawn hand-painted film (No. 1), he made two progressively more complex, batiked, geometrical animations (Nos. 2 and 3), colored by spray paint and dyes, also directly applied to the film. Then he began a series of photographed abstractions, first in black-and-white (No. 4), then in color (Nos. 5 and 7), with quantum leaps of intricacy at each stage. Nos. 10 and 11 integrate collage and fragmentary animated narrative into the spatial and color fields established in the earlier films. That narrative tendency expanded in No. 12 and would have reached an even greater elaboration had No. 13 been completed according to his plan. With the abandonment of that film, Smith turned from animation to the actual world for his imagery, but he maintained a plastic control over what he filmed by means of superimposition (No. 14) and the use of a kaleidoscope (The Tin Woodsman’s Dream, second part).

The regular curve of this progression, describing in its course several versions of hermeticism from Neo-Platonic formalism through ritual magic to shamanism traces a graph of evolving concerns and reveals an amazing patience, at odds with the language but not the sense of the film-maker’s comments on his work. Harry Smith was a practicing hermeticist. As much as his films share the central concerns of the American avant-garde cinema and incarnate its historical development, they separate themselves and demand attention as aspects of Smith’s other work. He divided his time among film-making, painting (less in recent years), iconology (he had a formidable collection of Ukrainian Easter eggs and had spent years practicing Northwest Indian string figures in preparation for books on these symbolic cosmologies), music (his reputation as an authority on folk music matches his reputation as a film-maker among experts), anthropology (Folkways issued his recordings and notes on the peyote ritual of the Kiowa), and linguistics (as an amateur, but with intense interest).

Since childhood Smith sustained an interest in the occult and in the machinery of illusionism:

My father gave me a blacksmith shop when I was maybe twelve; he told me I should convert lead into gold. He had me build all these things like models of the first Bell telephone, the original electric light bulb, and perform all sorts of historical experiments.… Very early my parents got me interested in projecting things.5

His father also initiated his interest in drawing by teaching him to make a geometrical representation of the Cabalistic tree of life. Smith even spoke of Giordano Bruno as the inventor of the cinema in an hilariously aggressive lecture at Yale in 1965, quoting the thesis of De Immenso, Innumerabilibus et Infigurabilibus that there are an infinite number of universes, each possessing a similar world with some slight differences—a hand raised in one, lowered in another—so that the perception of motion is an act of the mind swiftly choosing a course among an infinite number of these “freeze frames,” and thereby animating them. We see that Smith regards his work in the historical tradition of magical illusionism, extending at least back to Robert Fludd who used mirrors to animate books, and Athanasius Kircher who cast spells with a magic lantern.

In an interview in the Village Voice, he offered the following unexpected evaluation of his work as a film-maker among film-makers.

I think I’m the third best film producer in the country. I think Andy Warhol is the best. Kenneth Anger is the second best. And now I’ve decided I’m the third best. There was a question in my mind whether Brakhage or myself was the third best, but now I think I am.6

The smoothness of the diachronic outline of Smith’s development as a film-maker reflects the ease with which the formal and the hermetic poles meet in any given film along that graph. In the ensemble of his work, neoplasticism converges with Surrealism so undramatically that we are forced to see that the distances among the theosophy of suprematism, the Neoplatonism of Kandinsky and Mondrian, and the alchemical and Cabalistic metaphysics of Surrealism were not as great as among their respective spatial and tropic strategies. Harry Smith already occupied the new theoretical center where neoplasticism and Surrealism might converge.

The hermetic artist is one who finds the purification, or the formal reduction, of his art coincident with his quest for a magical center that all arts, and all consciousnesses, share. The paradox of hermetic cinema which we encounter in the later films of both Kenneth Anger and Harry Smith is that the closer it comes to self-definition the further it moves from autonomy, the more it seems to involve itself in allusion, arcane reference, obscurity. While most of his contemporaries found first the dream and then the myth to be the prime metaphors for cinema’s essence, Smith, following the same path, posited a moving geometry as its essence before he joined the others in a move to mythopoeia.

He defined the geometry of cinema in terms of its potential for complexity rather than reduction to simplicity. His early films are progressively more intricate. Yet his first film is remarkably sophisticated in its range of tactics.

No. 1, the most eccentric of Harry Smith’s animations, utilizes a principle of imbalance and unpredictability as a source of visual tension, which is reflected in several aspects of the film’s imagery and form. Its freely drawn, Arp-like figures resist precise geometry, and the base itself, when it becomes solid, has a tendency to leave a band of a different color at the right edge of the screen. Hard-edged squares are integrated rather uneasily into this context of fluctuation and eccentricity. A vibration occurs when they appear at the beginning, in the middle, and just before the conclusion of the film.

Positions and colors alternate quickly, jumping within the frame, as two squares move toward each other along a virtual diagonal, as in Eggeling’s film. Shapes change as soon as they are formed; amorphous circles turn into squares which open up to contain circles again. Only the original hard-edged squares resist transformation as they fall again in the middle of the film.

The instability of the base, which changes color, becomes texturally settled, and can dissolve into splatterings, reflects the ambiguity of the outlined forms which occasionally transform outside to inside. The filmmaker’s reference to “dirty shapes” in this film must refer to the vaguely phallic wedge in the middle of the film, which becomes a triangle with a hole through which a circle and a soft, again somewhat phallic, rectangle pass. Once the ground turns into the figure in the manner of Richter’s Rhythmus 21: a horizontal band expands in both directions, but before it wipes the previous base away it bends upon itself as if to become a new circle. As the outer shell dissolves, circles form within circles until the distinction between a circle and a square weakens. Four soft triangles, with holes in them, come together to suggest a rectangle. In the final appearance of the rigid squares, they again overlap to create a negative space, and they make the most complex set of variations in the film.

The difficulty of adequately describing No. 1 reflects the excessive instability of its imagery. Changes continually occur on at least two levels, that of figure and that of base; there are often two or more simultaneous developments on both levels, with perhaps one point of synchronization between one figural and one base change, while all else is asynchronous. This instability, which always seems about to resolve itself on the level of the figure, actually finds its satisfying conclusion, its unexpected telos, in the two flashes, first eight frames long, then eleven, of the irregular yellow and red shape—the chromatic climax of the film—just before the end.

In Nos. 2 and 3 Harry Smith abandoned the hand-drawn figure. He concentrated on the exhaustive use of the batiking principle by which he inserted the hard-edged squares into his first film. As he describes it in an interview in Film Culture Reader, that process involved placing “come clean” dots on 35mm film, spraying color on it, then covering the strip with vaseline before removing the dots. Another spraying will give two colors, one inside and one outside the circle. Of course the process can be multiplied with different colors.

This shift of technique implied a new dynamics for the films. In No. 1 the film-maker recognized the essential instability of a drawn line which has to repeat itself twenty-four times a second. He elaborated the whole form of his film out of this basic instability, exaggerating it and mimicking it in structural and textural ways. The batiking process removed the essential vibration of line. Smith responded to this fact with more rigorous rhythmic form, a heightened centrality of imagery, a smoother balance of colors, and a strict reliance on basic geometrical figures. In No. 2 in particular he explored the use of offscreen space implicit in the opening and in several moments of No. 1. By opening with and predominantly using motion from the top to the bottom of the screen, he introduced a sense of gravity around which the offscreen vectors are organized.

Several variations on the manifestation and rhythmic movement of the circle alternate through the film: (1) a circle defines itself out of the widening of a section by the expanding of two radii or disappears by inversion; (2) one circle or a phalanx of circles crosses the screen vertically or horizontally; (3) a circle collapses from its circumference inward or expands outward as far as or beyond the rectangle of the screen; (4) a circle splits into two semicircles to reveal another circle behind it; (5) fixed concentric circles; (6) a small circle turns within a larger one with a continual tangency of circumferences.

The reliance on primary colors emphasizes the purity and regularity of the film’s form. By making this directly on film with the batiked process rather than animating it from drawings as is possible, Harry Smith maintained the vibrancy of directly applied color with its frame-by-frame fluctuations which otherwise would be lost. There is also a minimum of arbitrary blending and/or an absence of color at the points where the circles meet the base. This and a discreet amount of flaking, especially on the inlaid squares, give the film a textural immediacy. With the geometric regularity of the circles and the structural regularity of the film’s construction, Smith has created a form in opposition to the color’s irregularity. The result is more successful than the opposite tactic employed in No. 1.

When Smith says that “the action takes place either inside the sun or in Zurich, Switzerland,” he is alluding to the hermetic source of the circle, the sun, and suggesting that the film might also take place in the mind of Carl Jung, then living in Zurich. His subsequent claim that No. 3 is the most complex hand-painted film ever made is sustained by its comparison with anything I have seen in this mode. The most ambitious aspects of No. 1 and 2 are merely preludes to the textural, rhythmic, and structural complexity of No. 3. It is not difficult to believe the film-maker when he says that it took him several years of daily work to complete it.

It falls into three sections. In the first a hatch made of four bars (two horizontal, two vertical, crossed over each other like a grid for playing tictac-toe) gradually turns into a field of squares, which in turn reveal a group of overlapping diamonds which are central to the second section. There the diamonds undergo a number of changes amid expanding rectangles (characteristic of the first part of the film) and circles (characteristic of the last part). The final third uses the image of the expanding circle to mount a spectacular climax integrating the previous strategies and images of the film.

This time the film-maker makes little use of offscreen space; he organizes much of the movement within the film in terms of the illusionary depth of the screen. Images recede into and explode out of a deep center. Emphasis is placed on the relative positions of foreground and background figures. The changes of color are more complex than in No. 2; solid hues rest beside clearly defined areas of splattered paint and when figures overlap their common areas take on different colors. Finally, different rhythmic structures mesh with a complexity equal to the most elaborate achievements of the entire graphic film tradition.

By the time he completed this film, Harry Smith had established contacts with other film-makers, both in the San Francisco area where he was working and in Los Angeles. It was at the same time that Frank Stauffacher and Richard Foster founded Art in Cinema, where avant-garde films, both those from the Europe of two decades earlier and new works, had their first rigorous screenings on the American West Coast. Although Smith continued to paint throughout this period, he came to identify himself with the emerging cinema. In fact, when Stauffacher and Foster split up and it looked as if Art in Cinema would fail (as it did), he tried for a brief time to program new films for it. It is nearly impossible to pin Smith down on specific dates within this period of the late 1940s and equally difficult to fix his movements precisely from other sources. Nevertheless we know that he worked in San Francisco and Berkeley during this time and that during this period he met John and James Whitney of Los Angeles, who were to have a decisive influence on him and later on Jordan Belson.

Between 1943 and 1944 the Whitney brothers had made Five Film Exercises on home-made animating and sound composing equipment. One of their highest ambitions was to produce “audio-visual music” or “color music” by the synchronization of abstract transformations to electronic sounds and by the utilization of basically musical forms for the overall construction of their films. In one article of 1944, they refer to Bauer, a source of inspiration they shared with Smith; in another, of 1945, they speak of Mondrian and Duchamp (in so far as he urged mechanical reproduction over hand-made objects of art) as primary inspirations. Their early films show hard-edged or sometimes slightly out of focus figures in a state of continual transformation and movement about the screen. A shape that seems to curve three-dimensionally will change to make its flatness apparent (Film Exercise 1); the whole screen or half the screen will flash with color flickers (Film Exercise 2 and 3); and behind geometrical variations; a reciprocal play of movement into and out of screen depth will structure a film (Film Exercise 4); or a process of echo and recapitulation in different colors will be an organizing principle (Film Exercise 5). Their own notes for the catalogue of Art in Cinema most clearly define their aspirations:

FIRST SOUND FILM; COMPLETED FALL 1943

Begins with a three beat announcement, drawn out in time, which thereafter serves as an imageless transition figure dividing the sections of the film. Each new return of this figure is condensed more and more in time. Finally it is used in reverse to conclude the film…

This film was produced entirely by manipulation of paper cut-outs and shot at regular motion picture camera speed instead of hand animating one frame at a time. The entire film, two hundred feet in length, was constructed from an economical twelve feet of original image material.

FRAGMENTS; SPRING 1944

These two very short fragments were also made from paper cutouts. At this time we were developing a means of controlling this procedure with the use of pantographs. While we were satisfied with the correlation of sound and image, progress with the material had begun to lag far behind our ideas. These two were left unfinished in order to begin the films which follow.

FOURTH FILM; COMPLETED SPRING 1944

Entire film divided into four consecutive chosen approaches, the fourth being a section partially devoted to a reiteration and extension of the material of the first and second sections.

SECTION ONE: Movement used primarily to achieve spatial depth. An attempt is made to delay sound in a proportional relationship to the depth or distance of its corresponding image in the screen space. That is, a near image is heard sooner than one in the distance. Having determined the distant and near extremes of the visual image, this screen space is assigned a tonal interval. The sound then moves along a melodic line in continuous glissando back and forth slowing down as it approaches its point of alternation direction…

SECTION TWO: Consists of four short subjects in natural sequence. They are treated to a development in terms alternately of contraction and expansion or halving and doubling of their rhythm. Sound and visual elements held in strict synchronization….

SECTION THREE: A fifteen second visual sequence is begun every five seconds after the fashion of canon form in music. This constitutes the leading idea, a development of which is extended into three different repetitions. This section is built upon the establishment of complex tonal masses which oppose complex image masses. The durations of each are progressively shortened. The image masses are progressively simplified and their spatial movement increasingly rapid.

SECTION FOUR: Begins with a statement in sound and image which at its conclusion is inverted and retrogresses to its beginning. An enlarged repetition of this leads to the reiterative conclusion of the film.

FIFTH FILM; COMPLETED SPRING 1944

Opens with a short canonical statement of a theme upon which the entire film is constructed. Followed by a rhythmical treatment of the beginning and ending images of this theme in alternation. This passage progresses by a quickening of rhythm, increasing in complexity and color fluctuation…

A second section begins after a brief pause. Here an attempt is made to pose the same image theme of the first section in deep film screen space. As the ending image recedes after an accented frontal flash onto the screen it unfolds itself repeatedly leaving the receding image to continue on smaller and smaller.7

Harry Smith credits the Whitneys both with teaching him the techniques of photographic animation and with helping him to formulate a theoretical view of cinema.

He remained faithful to the circle, the triangle, and the square or rectangle as the essential forms of visual geometry. Before the black-and-white imagery of No. 4 begins, Smith pans the camera over a painting of his from the same period. The movements on the painting are in color. In contrast to his film work, the painting uses organic, bulb-like forms rather than rigid geometrical figures. In Film Culture he described this painting:

It is a painting to a tune by Dizzy Gillespie called “Manteca.” Each stroke in the painting represents a certain note on the recording. If I had the record, I could project the painting as a slide and point to a certain thing.8

The possibility of translating music into images is another part of the hermetic worldview. In practice Harry Smith’s use of sound with film has been very problematic. The initial three painted films were made to be shown silently. After they were finished, the film-maker had the following experience: “I had a really great illumination the first time I heard Dizzy Gillespie play. I had gone there very high, and I literally saw all kinds of color flashes. It was at that point that I realized music could be put to my films.” He claims that he then cut down No. 2 from an original length of over thirty minutes to synchronize it with Gillespie’s “Guacha Guero.” Neither the original long version nor the synchronized print survive.

Smith was notoriously self-destructive. The loss of several important films from his “Great Work” attests to this. He proved in films like No. 11 and No. 1 2 that he could use both music and sound effects meticulously, and in the case of the later film, with genius. His ability in handling sound makes all the more alarming the extreme casualness with which he put the Beatles’ first album with an anthology of his early films, Early Abstractions, for distribution. It seems as if he wanted to obscure the monumentality of his achievement in painting and animating film by simply updating the sound track.

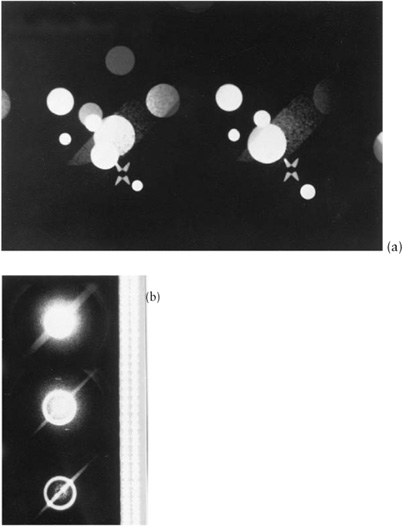

Geometrical abstraction in (a) Harry Smith’s No. 7 and (b) No. 5: Circular Tensions.

No. 4 combines camera movement with superimposition to create a dance of white circles and squares against a black background. Because of the absence of any perspective, the bobbing and swinging of the camera is translated by the eye into a movement of lights within or across the screen. By altering his speed of movement, the distance from the object, and the direction of the camera, he can elaborate a formal interplay of counterpoint, scale change, and off-screen orientation out of a simple grid of twenty-four white squares and a field of circular dots.

No. 5, entitled Circular Tensions, extends the use of the moving camera and superimposition into color and geometry. Against a black background a green square appears next to a red circle and triangle. Slowly they begin to move around and over one another. Then an eccentrically composed blue spiral appears dimly in superimposition, giving an illusory depth to the black space behind the geometrical figures. Numerous bright yellow lights sweep across the screen in different directions, leaving in their wake a bounding red circle. Its scale remains constant as the camera zooms in and out on superimposed rectangles.

In the late 1940s Harry Smith and Jordan Belson invited Hilla Rebay of the Museum of Non-Objective Art (now the Guggenheim Museum) to see their paintings when she was in San Francisco. That visit ultimately resulted in a grant from the Solomon Guggenheim Foundation during 1951 for Smith to begin work on No. 7. When he moved to New York at the completion of the film, he was again helped by Hilla Rebay and given a studio in the Guggenheim Museum. At that time the Guggenheim Museum specialized in collecting the works of Kandinsky and Bauer. Of all of his films, No. 7 comes the closest to animating a painting of Kandinsky in his geometrical style of the 1920s.

To make this film, Smith set up a primitive, back-screen projection situation that worked with astonishing precision. One machine projected black-and-white images on a translucent screen. On the other side of the screen a 16mm camera re-recorded them. A wheel of color filters in front of the camera was used to determine the hue of a figure or a background. By keeping an accurate record of where any pattern was recorded on the film strip, the film-maker could make elaborate synchronous movements by means of several layers of superimposition. Most of the visual tropes of No. 7 derive from earlier animations of Smith’s; but here they attain their apogee of intricacy and color control. No use is made of offscreen space. Illusory depth orients the entire film, but, unlike the earlier films, there is a tension here between images which have their center of gravity in the absolute center of the screen and sets of images with two or more lateral centers.

The film-maker’s note divides the film into four parts. In the first, if my division is accurate, the following tropes are dominant: (1) colored bars appear vertically, horizontally, or diagonally against the background and widen to the edges of the screen until they become the backdrop; (2) rings within rings of the same or different colors expand from the center of the screen; (3) two laterally placed circles, one larger than the other, emerge and recede alternately from two points of gravity, exchanging their relative scales in each alternation; (4) a central black circle enlarges with a vaguely defined red corona; (5) circles and rings, in different colors, come out of screen depth simultaneously, and the area of their overlapping takes on new colors; (6) an expanding square alternates between being black within against a diminishing colored space and colored within against a black space; (7) amid these intricate variations of orderly patterns, eccentrically placed squares, circles, and squares containing circles appear; (8) different parts of the screen change at different speeds. A deep red accents the first section.

In the second section the tonality shifts to a bluish-green with considerable use of red and white. Here the triangle makes its first appearance, initially in sequential sets of four wedges exploding outward, later with as many as sixteen wedges in eight concentric rings. Generally, the placement of figures is more irregular than in the earlier section and the rhythmic interactions even more complex, because the central organizing pulse itself can suddenly fluctuate. When black circles with colored coronas appear, complex explosions of rings of wedges are syncopated within them. As the film progresses, the pace of the explosions increases.

In the third section the importance of the circle diminishes; it only appears at the end. The square and the rectangle take the center now. All over the screen there are squares, grids, and bars. There is no break in the continual blending of different kinds of grids and squares throughout this section. This is the most decentralized part of the film. Throughout it, there is a periodic but repressed background of exploding wedges. Towards the end of the section a dialectic establishes itself between eccentricity and centrality, in which the shift of axes of the wedges plays a decisive role.

The final quarter of the film derives its pulse from the continual expansion of rings from the center of the screen. In opposition to this dominant trope: (1) fast moving sets of radiating rings appear eccentrically; (2) circles grow out of pie-like sections (as in No. 2) and reduce themselves to sections; (3) squares emerge, turn into grids, and dissolve into blackness; (4) a single red triangle wanders around the screen and disappears in its center with an explosion of wedges; and (5) squares appear within squares.

After finishing No. 7, Harry Smith moved from San Francisco to New York. There he began to make collage films. Unfortunately, all we know of No. 8 and No. 9 are his laconic notes. By the time he made No. 10 and No. 11, which are versions of the same film, he had a highly developed collage animation technique in color. Many of the formal operations of the earlier films, especially No. 7, were incorporated into these two films. Of the several modes of tension in these works, the relationship between the screen as an enclosed world and offscreen space is particularly important. Similarly, the dialectics between a flat plane of action and illusory depth, between collage animation and abstract convulsions of the whole image, between gravity and the screen as an open field of movement, between sequences of transformation and abrupt change, derive from and elaborate upon the strategies of his earlier films.

Both No. 10 and No. II are pointedly hermetic. They describe analogies among Tarot cards, Cabalistic symbolism, Indian chiromancy and dancing, Buddhist mandalas, and Renaissance alchemy. The process of animation itself, with its continual transformations, provides the vehicle for this giant equation. Surrealism’s version of the hermetic enters in at least twice, rupturing the logic of the occult analogies through unexpected and irrational juxtapositions. The first of these inclusions is a postman in a child’s wagon, who plays an important role in the film because of his resistance to being transformed. The second is the comic appearance of a grimacing woman, looking out of a window near the end of both films. The presence of such imagery, which jars the consistency of the film, provides yet another dialectic and paradoxically enriches the hermeticism it is confounding by distancing it from the rational.

A detailed description of these films, shot as they are, would require a volume. So many of the fleeting collages are composed of internal subcollages, associating within a single shape the iconography of different cultures, that several pages would be needed to describe each one’s presence, which lasts on the screen perhaps a second, before one could go on to the shape it changes into. Beyond that there is a welter of images and symbols moving around or behind the central image at many points in the film. In short, Harry Smith is utilizing cinema’s potential, through its speed, to confound the perception of the spectator with a profusion of complex imagery.

No. 10 begins with snow crystals falling through the frame. They become a molecular cluster with an abstract circumference of outward pointing red wedges. The atoms of the molecule separate to become the tree of life, an outlined figure with ten points which is the central Cabalistic diagram. A bird lands on it, turning it into a skeleton with various totemic masks. The most dynamic and most often employed illusion of depth in the film emerges from the creation of a recessed room or theater whose walls are receding planes of different colors. As on a stage, it looks as if a fourth wall has been removed so we can see within.

The first appearance of this theater coincides with the breakup of the skeleton and its reformation as a masked shaman, who floats upward through the ceiling and off-screen, leaving the space empty for a moment before it fades out. Soon an athanor (a basic piece of alchemical equipment) encloses an unsupported flame in the center of the room. In the earlier films an act of enclosure, of circles within a square, for example, almost always initiated a chain of transformations of the forms within the framing device at a rhythm all its own. So too here, enclosures generate interior metamorphoses. The fire constantly changes its shape, becoming birds and alchemical symbols, while the legged mask continues to circle the stage.

Against a black background an Indian dancer floats down from the top of the screen on a pill box. An entire constellation of symbols fuses into the back of a playing card. When the dancer crosses in front of it, she leaves her shadow on the card. Her dance is synchronously reflected in the shadow. Although she will soon be transformed, her image will reappear again, for she is the central female presence in No. 10.

Throughout the transformations of the dancer, her shadow remains on the back of the card. The shadow dances by itself, sending out a lightning stroke which creates a postman on a red wagon. He will become the central male figure of the film, the dancer’s counterpart. At the completion of the dance the shadow becomes the dancer, and she and the postman, both inscribed in rings, orbit one another, while a series of rays emanate from the center of the screen.

The spatial dialectic of the film now becomes more intricate. Layers parallel to the plane of the screen tend to move or fracture to reveal another plane immediately behind it. This happens, for instance, when an object floats down-screen revealing the postman behind it. But when he tries to reach the dancer, the theater reconstitutes itself, now subdivided into barriers which frustrate his pursuit.

The moon descends from covering the whole screen to an arc with a black spot above it. From behind flies an orbiting planet, followed by a stork. Then a mushroom and the Rosetta Stone grow out of the moon. The dancer steps from in back of one stone; from the other the postman. They step behind these objects again and reappear as doubles: two identical dancers and two postmen.

The dancers and postmen join hands beside and on top of each other in chiastic order, while the moon descends, leaving them floating in space. In quick succession they change into a tree of life; a bird above three serpents holding the sun, the moon, and the earth; and a headless man, standing on the earth holding the sun and moon in his hands while small squares gush from his neck. He becomes a smaller version of the moon than the one that has just descended. A Tibetan demon appears behind that moon and carries it away in his mouth, while the couple float by on a cerebrum, leaving a conch, which turns into the end title.

Most of the imagery of No. 11, or Mirror Animations, is identical to that of No. 10. The film differs essentially in that it is carefully synchronized to Thelonius Monk’s “Mysterioso.” Most of the significant scenes of the earlier film recur here with slight variations; the dance of the Indian and her shadow, the pursuit within the subdivided theater, the chiromantic variations, and the grimacing woman in the window, which has become a picture frame all appear in approximately the same sequence. The tree of life, the snake, the symbols of the sun, moon, Hermes and Neptune within the pillbox, the Tarot cards, and the athanor present themselves in altered contexts. The Buddhist and Tibetan imagery, as well as the entire end of the film from the appearance of the moon on, are absent.

The most prominent innovation in No. 11, a priestess dressed in white who is created at the beginning of the film when lightning strikes a snowflake, generates rhythmic and structural differences. Her priestly gestures are synchronized to the pulse of Monk’s music. Her centrality at the beginning and end of the film finds reinforcement in regular movements of figures and triangles of light around all four sides of the screen. The transformations occur within the metrical pattern established by the movements of her arms, even when she is not on the screen. Her presence and the way she brackets the whole film diminish the roles of the dancer and the postman.

Despite some elaborations on the spatial strategies of No. 10, such as a scene in which the snake wraps itself around the back of the recessed theater and snatches a figure within it, No. 11 underplays the dialectic of depth and plane, so important in the earlier film. There are less convulsive changes in the depicted screen space. The whole film seems to move more slowly, and the dazzling flood of imagery is somewhat chastened.

This chastening and the presence of the priestess as the mediator and controller of the operations of the film forecast the radical jump in style to No. 12. This film, sometimes called The Magic Feature or Heaven and Earth Magic, is Harry Smith’s most ambitious and most difficult work. Although it is particularly difficult to assign dates to the animated films he made in New York, No. 12 seems to have occupied him through most of the 1950s, especially toward the end of that decade.

The original conception of this film exemplifies the myth of the absolute film in its expansive form. The hour-long version that can be seen today is but a fragment of the original plan, but even so, it is among the very highest achievements of the American avant-garde cinema and one of the central texts of its mythopoeic phase.

In the interview published in Film Culture, the film-maker describes the plan for the whole film:

I must say that I’m amazed, after having seen the black-and-white film (#12) last night, at the labor that went into it. It is incredible that I had enough energy to do it. Most of my mind was pushed aside into some sort of theoretical sorting of the pieces, mainly on the basis that I have described: First, I collected the pieces out of old catalogues and books and whatever; then made up file cards of all possible combinations of them; then, I spent maybe a few months trying to sort the cards into logical order. A script was made for that. All the script and the pieces were made for a film at least four times as long. There were wonderful masks and things cut out. Like when the dog pushes the scene away at the end of the film, instead of the title “end” what is really there is a transparent screen that has a candle burning behind it on which a cat fight begins—shadow forms of cats begin fighting. Then, all sorts of complicated effects; I had held these off. The radiations were to begin at this point. Then Noah’s Ark appears. There were beautiful scratchboard drawings, probably the finest drawings I ever made—really pretty. Maybe 200 were made for that one scene. Then there’s a graveyard scene, when the dead are all raised again. What actually happens at the end of the film is everybody’s put in a teacup, because all kinds of horrible monsters came out of the graveyard, like animals that folded into one another. Then everyone gets thrown in a teacup, which is made out of a head, and stirred up. This is the Trip to Heaven and the Return, then the Noah’s Ark, then The Raising of the Dead, and finally the Stirring of Everyone in a Teacup. It was to be in four parts. The script was made up for the whole works on the basis of sorting pieces. It was exhaustingly long in its original form. When I say that it was cut, mainly what was cut out was, say, instead of the little man bowing and then standing up, he would stay bowed down much longer in the original. The cutting that was done was really a correction of timing. It’s better in its original form.9

Although the film was shot in black-and-white, he built a projector with color filters that could change the tint of the images. Furthermore, the whole film was to be projected through a series of masking slides which would transform the shape of the screen. The slides take the form of important images within the film, such as a watermelon or an egg. Thus the entire movement would be enclosed within the projection of the slide. A different filter could determine the color of the surrounding slides. The whole apparatus functioned only once. In the late 1950s or early 1960s he presented the film for potential backers at Steinway Hall in New York. He would have liked to have installed seats in the form of the slide images—a watermelon seat, an egg seat, etc.—with an electrically controlled mechanism that would have changed the colors and the slides in accordance with the movements of the spectators in their seats. Lacking the extravagant means necessary to achieve this, he manipulated the changes by hand.

Despite the multiplicity of their references and obscure allusions Nos. 10 and 11 offer easier access to the viewer than No. 12. Here Smith avoids historical iconography, with the possible exception of the universally understood skeleton. The form of the film evokes hermetic maneuvers, which are all the more distanced because of their abstraction and lack of specificity. The tone of the film seems to call for a close reading which the form frustrates. Furthermore, the investigation of his sources, which he alludes to obliquely in his note on the film, opens up seemingly fruitful approaches to the film without ever providing satisfying insights.

The note veers from an elliptical description of the film’s images to allusions about its sources. When he writes, “Next follows an elaborate exposition of the heavenly land in terms of Israel, Montreal and the second part depicts the return to earth from being eaten by Max Muller on the day Edward the Seventh dedicated the Great Sewer of London,” he is deliberately obscuring the film with hints about it. By Israel he means the Cabala, particularly the three books translated by MacGregor Mathers as The Kabbalah Unveiled: “The Book of Concealed Mystery,” “The Greater Holy Assembly,” and “The Lesser Holy Assembly.” Here the Cabalists interpret the tree of life in terms of the body of God, with intricate and detailed descriptions of features, members, configurations of the beard, and so on.

The reference to Montreal, he later explained, indicates the parallel influence of Dr. Wildner Penfield of the Montreal Neurological Institute, whose extensive open brain operations on epileptics are described in Epilepsy and the Functional Anatomy of the Human Brain (Little, Brown, Boston, 1954). Several aspects of Penfield’s book intrigued Smith: the hallucinations of the patients under brain surgery; the topology and geography of the cerebral cortex; and the distribution and juxtaposition of nervous centers. His occasional remark that No. 12 takes place in the fissure of Silvius, one of the major folds in the brain, is another allusion to Pen-field.

A photograph of Max Muller, the nineteenth-century philologist and editor of The Sacred Books of the East, actually appears in the film. What Smith does not say is that this is the only face, out of several, which has a specific reference. Naturally, Smith’s identification of this figure, which has a privileged place in the film, leads us to wonder, fruitlessly, who the other Victorian visages might be.

Finally, the allusion to the day the London sewers were inaugurated turns out to refer to the cover story of an illustrated magazine that provided many of the elements of the collage. The very choice of late-nineteenth-century engravings as the materials for his collage brings to mind the influence of Max Ernst’s books, La Femme 100 Têtes and Une Semaine de Bonté. As we shall see, there are other, structural links with Ernst in this film.

The broadest outline of the “action” of No. 12 agrees with the filmmaker’s ironic note. As in No. 10, there are two main characters, a man and a woman; but here the man assumes the role of the priestess from No. 11, not that of the postman. Although Smith has described him as having the same function as the prop-mover in traditional Japanese theater, his continual manipulations in the alchemical context of No. 12, coupled with his almost absolute resistance to change when everything else, including the heroine, is under constant metamorphosis, elevates him to the status of a magus. According to the argument of the film, he injects her with a magical potion while she sits in a diabolical dentist’s chair. She rises to heaven and becomes fragmented. The “elaborate exposition of the heavenly land” occurs while the magus attempts a series of operations to put her back together. He does not succeed until after they are eaten by the giant head of a man (Max Muller), and they are descending to earth in an elevator. Their arrival coincides with an obscure celebration, seen in scatological imagery (the Great Sewer), in which a climatic recapitulation of the journey blends into an ending which is the exact reversal of the opening shots.

The reader of Dr. Penfield might identify the injection of the heroine and the subsequent explosion of her cranium with the effects of open brain surgery on the conscious patient. Since the operation is painless, after a local anesthetic has been applied to the surface of the skull, Penfield had his patients talk while he probed their brains with his surgical needle. Individual patients’ visions, memories, sensory illusions, and motor reactions when particular areas of their brains were touched were recorded by Penfield in numerous case histories.

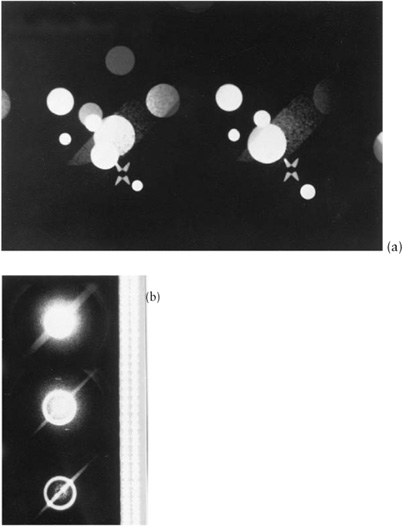

(a) Harry Smith’s No. 12: The initial scene.

(b) The ascent to heaven on a dentist’s chair.

(c) The skeleton juggling a baby in the central tableau of heaven.

(d) Max Muller casts a spell on the Magus.

(e) The return to the initial scene.

A significant case of the fusion of a religious cosmology with mental disorder would be Daniel Paul Schreber’s Memoirs of My Nervous Illness.10 Harry Smith first brought this book to my attention in a context unrelated to No. 12, but later he referred to the first tableau after the ascent as “Schreber’s heaven.” In the book, a well educated, influential German jurist vividly describes two periods of extreme paranoia in 1884 and 1893. The text is neither clinical nor apocalyptic. Although Schreber sees himself as mentally disturbed, he presents his fantasies as metaphysical revelations and himself as the privileged martyr to these insights. In essence, his thesis is that God attracts human nerves to the “forecourts of heaven.” Among his numerous paranoid hallucinations were the ideas that he had contact on the nerve plane with other people, which they refused to admit in the flesh; that his stomach had been replaced with an inferior one; and that the boundaries of male and female were confused within him. Freud wrote a psychoanalytical study of the book, finding in it a psychosis based on homosexual fears. Harry Smith seems to be interested in it, as in all psychological phenomena, because of the quality of its imagination.

Schreber’s father, Daniel Gottlob Moritz Schreber, was a physician and author of a very popular exercise book, Medical Indoor Exercises. From this book Smith took the character of the magus. By cataloguing the illustrations for the exercises, he collected a sequence of gestures which he animated into all the movements of the film’s main character.

What makes No. 12 much more complicated than its argument and what obscures its outlines is the multiplicity of details filling the images and the refusal on the part of the film-maker to indicate levels of importance among these details. For example, before the dentist’s chair can be used, it must be adjusted. A bird might lay an egg, out of which comes the hammer with which the magus can transform the dentist’s chair. Other figures carry out bottles, mortars and pestles, and enema bulbs to prepare a liquid with which to oil the chair, and an almost identical set of operations is repeated for the preparation of the potion to be injected into the heroine. Since the viewer never knows the desired end of an operation or a series of operations, he must divide his attention evenly among these endless and varied procedures.

In addition to this, countless creatures and things are crossing the screen while these actions are going on—a dog, a cat, a skeleton horse, a walking house, a cow, a sheep, two spoon-like creatures, an homunculus, birds. At times they contribute to the operation at hand, but just as often their participation is deliberately obscure.

The technique of distancing the dramatic focus of a story behind a continual foreground of evenly accented detail is a literary tactic dating from the novels of Raymond Roussel, before the First World War, and periodically revived, most recently in the plays of Richard Foreman. In No. 12 Harry Smith has offered its hypostatic equivalent in cinema. His continual alternation of associative and disassociative sound effects underlines this distancing; for as often as he will synchronize the sound of a dog barking when the dog crosses the screen or of screams when the woman is being dismembered, he will connect mooings with a horse, suddenly inject applause, or preface or follow an event with the sound appropriate to it.

Perhaps even more disorienting than the pressure of detail or the dialectic of sound is the random combination of certain recurrent images. Like Brakhage in Prelude: Dog Star Man, Harry Smith found a way of incorporating chance operations in his film without sacrificing its structure. In Film Culture he says:

All the permutations possible were built up: say, there’s a hammer in it, and there’s a vase, and there’s a woman and there’s a dog. Various things could then be done—hammer hits dog; woman hits dog; dog jumps into vase; so forth. It was possible to build up an enormous number of cross references.11

I tried as much as possible to make the whole thing automatic, the production automatic rather than any kind of logical process. Though, at this point, Allen Ginsberg denies having said it, about the time I started making those films, he told me that William Burroughs made a change in the Surrealistic process—because, you know, all that stuff comes from the Surrealists—that business of folding a piece of paper: One person draws the head and then folds it over, and somebody else draws the body. What do they call it? The Exquisite Corpse. Somebody later, perhaps Burroughs, realized that something was directing it, that it wasn’t arbitrary, and that there was some kind of what you might call God. It wasn’t just chance.12

I never did finish that sentence about the relation of Surrealism to my things: I assumed that something was controlling the course of action and that it was not simply arbitrary, so that by sortilege (as you know, there is a system of divination called “sortilege”) everything would come out alright.13

Smith’s use of chance coincides with his idea of the mantic function of the artist. He has said, “My movies are made by God; I was just the medium for them.” The chance variations on the basic imagistic vocabulary of the film provide yet another metaphor between his film and the Great Work of the alchemists. For the Renaissance alchemist, the preparation of his tools and of himself equalled in importance the act of trans formation itself. Since every element in an alchemical change had to be perfect, each instrument and chemical had its own intricate preparation. Alchemical texts tend to read like endless recipes of purification, firemaking, etc. The commitment to preliminaries is so strong that in its spiritual interpretation, alchemy becomes the slow perfection of the alchemist; the accent shifts from goals to processes. The viewer of No. 12 finds himself confronted with repetitive scenes of preparation—an egg hatches a hammer, which changes a machine, which will produce a liquid, etc.—toward a telos that brings us back to the beginning. The characters of the film end up precisely as they were at the beginning. Everything returns to its place of origin.

No. 12 shares with the mythopoeic cinema of Brakhage, Anger, and Markopoulos the theme of the divided being or splintered consciousness which must be reintegrated. As I have shown in the previous chapters, this theme is an inheritance from Romanticism. In Smith’s version of the myth, heaven and the human brain are conflated. When the physically divided woman first arrives in heaven she is seen within the frame of a female head. Her release from the anxieties of selfhood comes at the end of the film when the elevator brings her back to earth, down through the titanic body of Max Muller, who is last seen circumscribed by the same female head. Her disappearance from the action of the middle of the film cannot be construed as an escape from her anxiety, which I have called selfhood; these are her moments of maximal fragmentation, when all of the magus’ efforts are directed at bringing her back, or at least preparing the tools to do so.

Although there is no movement into or out of screen depth, various strategies are employed to suggest, at times, a recess of space there. The radiating balls, which help to create the illusion of ascent and descent to and from heaven, are the first of these. A room or theater is suggested immediately afterward in the first of the heavenly landscapes. Finally, the image of the Great Sewer, the last backdrop of the film, gives the impression of a group of receding arcades.

Among the more interesting spatial strategies in No. 12 are the sudden manifestations of the law of gravity. Through most of the film, figures simply move along virtual horizontal lines imagined within the black background. They do not need the support of a floor or structure to keep from falling out of the frame. But occasionally, as when the arch forms in the lower part of the screen, such support suddenly becomes necessary. The most dramatic use of this change of pace occurs during the episode in which a line of couches descends vertically down the screen. They create a void within the screen. The magus cannot pass without leaping on to one of the passing couches for support. His alternative, of course, is to float over the void by using the umbrella.

A related configuration of space within the black background would be the series of arches through which the magus walks or rides on the couch-boat. Normally, passage across the screen is smooth, along a single plane. When he begins to pass through arches by crossing in front of the right-hand pillar and behind the left-hand pillar of the arch, a sense of depth emerges without the illusion of diminishing into the vanishing point of the screen.

The circularity of the film’s form, the use of nineteenth-century engravings, and above all the theme of the mutable woman recall Max Ernst’s collage novel, La Femme 100 Têtes (1929), whose title in French puns as the woman with 100 (cent) heads or the woman without (sans) heads. That novel, in collage pictures, begins and ends with the same image. Within it are sections and subsections built on varying degrees of thematic and narrative sequence. Whenever a series of plates has a specific narrative and therefore temporal logic, Ernst introduces another image or images into the collage which does not follow the same unity of time or scale.

The collages abound in complex machinery and scenes of violence and dismemberment. Studying the images in sequence, the reader experiences promises of narration which continually evaporate or transform into chains of metaphor. The ultimate unity of the book is that of the dream. Harry Smith has said that he let his dreams determine the filming of No. 12. According to his account, he slept fitfully in the studio where he was filming for the entire year in which the film was being shot. He would sleep for a while, then animate his dreams. The exact relation between his dreams and the structure of the film is ambiguous, unless we can suppose that he dreamed the life of the figures he had already cut out and assembled for his film. What is more likely is that he established an intuitive relationship between the structure of his dreams and the substructure of the film.

In 1971 at Anthology Film Archives Smith spontaneously delivered a lecture to a group of students he happened upon in that theater. As they were looking at a film, not by him, in the realist tradition—a film of photographed actuality—he said, “You shouldn’t be looking at this as a continuity. Film frames are hieroglyphs, even when they look like actuality. You should think of the individual film frame, always, as a glyph, and then you’ll understand what cinema is about.”

It is certainly true that within Smith’s own work the hieroglyph is essential. When he finally began to shoot actualities for No. 14 (1965), he translated the spatial and temporal tactics of his earlier films into superimposed structures. From an opening reel—for the film is made up of whole, unedited one hundred foot reels of film multiply-exposed in the camera—in which relatively flat and carefully controlled surfaces (a composition of a store window or animated objects) are laid upon images of depth (receding night lights or rooms), the film proceeds to more random conjunctions of autobiographical material, from interiors to exteriors, from richly orchestrated colors to washed-out browns. In the final reels, the film gradually retraces its formal course, returning to the animated precision, spatial dialogue, and surface texture of the opening. In the center of the film Smith himself gets drunk while discussing his project for a recording of the Kiowa peyote ritual with Folkways records, and after a passage of leader—he did not even cut off the head and tail leaders that were attached to the individual rolls—we see the Kiowa and their environment. It is as if he had opened up his hieroglyphic art to make a space for a limited self-portrait.

Later he managed to fuse animation directly to live photography when he combined “The Approach to Emerald City,” the most complete of the surviving fragments of No. 13, with a sequence he shot in 1968 with a teleidoscope (a projecting kaleidoscope of his own construction) in order to make The Tin Woodsman’s Dream. The temporal hiatus between the two parts of this film apparently means nothing to Smith, who sees the whole of his work, not just his cinema, as a single edifice.

Jordan Belson, Smith’s closest associate in their early years in San Francisco, has made a contribution to the graphic film of comparable magnitude. Curiously, like Smith, he made a teleidoscopic film, Raga (1959), as well as at least one effort at dealing with actual surfaces with the control of an animator, Bop Scotch (1953). But proceeding from an attitude towards time and the working process diametrically opposed to Smith’s, he has suppressed these films. In Belson’s formulation of the absolute film, at least until 1970, the newest work is the only present film; it subsumes and makes obsolete his earlier achievements.

Belson is aware of the philosophical consequences of such a commitment to the all-consuming present. He is reticent about discussing his own past, and what he does say of it underlines his distance from it. Interestingly, that reticence extends to discussions of the “past” of the very films he willingly exhibits, particularly the techniques of their making. Yet he is eager to discuss the spiritual sources of his films. This is not inconsistent, as the films aspire to incarnate those source experiences and save them from time. They are transcendental, and their maker is a transcendentalist.

Jordan Belson too began his career as a painter and soon allied himself with Smith and the Kandinsky-Bauer tradition, although, to judge from his scrolls from the early fifties, he never committed himself to hard-edged geometry. Instead, he located his style in proximity to the later paintings of Kandinsky in which the rigidly defined forms give way to a more atmospheric abstractionism and a painterly treatment of line and shape.

The few early films I have managed to see grow out of and inform the paintings, for there is an undisguised will toward movement in the scrolls. Belson graduated from the California School of Fine Arts in 1946 (just two years before Peterson gave his first film-making course there), and the next year, inspired by the screenings at Art in Cinema, he made his first film, Transmutation (1947), which is now destroyed. According to the film-maker, it was made under the immediate inspiration of seeing Richter’s Rhythmus 21. Improvisations #1, from the following year, is also lost.

The earliest surviving films date from the beginning of the 1950s: Mambo (1951), Caravan (1952), Mandala (1953), and Bop Scotch (1953). The first three describe a gradual movement toward meditative imagery and rhythms. From the rather expressionistic oval forms, bright colors, and calligraphic designs of Mambo, which at times resembles the texture of William Baziotes’s paintings, Belson refined his imagery in Caravan, emphasizing both the geometrical (radiating circles against moving backgrounds) and the biomorphic (serpentine and spermatoid shapes). Although the yin-yang emblem finds its way into Caravan, it is the subsequent film, Mandala, that definitively aspires to be an object of meditation in the Easter tradition, as its name indicates. The geometry of Mandala is even more emphatic than in the earlier film. The transformations are slower, and there are discrete jumps in positions. For the first time a discrete pulse gives a regular rhythm to the entire film.

After another period of concentration on his painting, Belson was led back to cinema after collaborating with the composer Henry Jacobs on the Vortex concerts of abstract and cosmic imagery with electronic sound at the San Francisco Planetarium (1957–1959). Of the finished and abandoned films from this period, Flight (1958), Raga (1959), Seance (1959), Allures (1961), LSD, and Illusions (dates uncertain), the author has seen only Allures and the teleidoscopic film Raga. They represent the termination of his initial conception of cinema and forecast the transition to his mature style, which emerges after still another renunciation of cinema—this time in a profound despair over the value of art. Simply stated, the early films, up until and including Allures, are objects of meditation. The subsequent works, his nine major films, describe the meditative quest through a radical interiorization of mandalic objects and cosmological imagery.

Allures is actually the filmic result of Belson’s experience with the Vortex concerts in the late fifties. Although it blends images of becoming and apperception (dissolving and congealing spheres, color flickers, hot spots of light) with its predominantly geometrical and mechanically symmetrical patterns, it comes short of delineating a perceptual process in its overall structure. These moments of organic metamorphosis bind together and bracket the electro-astronomical imagery (expanding rings, receding circles, emerging spirals, eclipses, oscilloscopic lines, dot grids, and spheres of orbiting pin-point lights) which forms the center of attention in the film.

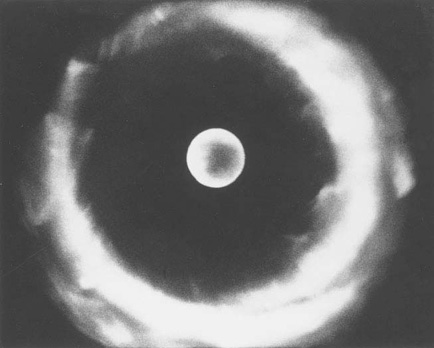

Belson acknowledges a debt to James Whitney as his instructor in the mandalic potential of the graphic film. Aside from the film exercises he made with his brother John, James Whitney has made two films of his own, Yantra (1950–1955) and Lapis (1963–1966). The latter is the most elaborate example of a mandala in cinema. It utilizes a field of tiny dots, symmetrically organized in hundreds of very fine concentric rings, to generate slowly changing intricate patterns which are most precise in the center of the wheel, disintegrating at the outer rings. The film consists of movements into the center of this wheel of dots, which at first expands beyond the borders of the frame, and movements away from it, showing its circular boundaries. Changes of color, scale, speed, and dot pattern attend the visual movements, but they are orchestrated in time so as to suggest a formal circle, the opening images and color flicker being almost exactly repeated at the end. Both structurally and visually Lapis conforms to the circular form of the mandala; its elaborate movements belie a fundamental stasis.

None of Belson’s early films are classical mandalas, but they all have the objective of being vehicles of meditation. According to the film-maker, they represent the “impersonal” phase of his career. That single word describes the fate of modernist geometrical art in the American avant-garde film. Like the trance film, the graphic film flourished in the first years after the war and then failed to sustain its vitality into the 1950s. We have seen how Harry Smith’s art veered from the geometrical to the mythopoeic without abandoning animation, and in the next chapter I shall show how the graphic film was renewed in Europe by an American and an Austrian. Belson’s successive resignations from film-making, James Whitney’s retirement after Lapis, John Whitney’s silence until the cybernetic alternative renewed his inspiration in the late 1960s, and Len Lye’s fate, all attest to the exhaustion of a formalist cinema in America.

When Belson gave up film-making in the early sixties, he diverted his creative energy to the practice of Hatha yoga. When the Ford Foundation offered him one of their coveted $10,000 grants in 1964, he turned them down. But after reconsidering, he accepted the money and reentered filmmaking with Re-Entry, the first of his “personal” films. For Belson the opposition of impersonal to personal art does not indicate an antithesis of geometrical formalism to Expressionism. As a yogi, Belson seeks the transcendence of the self. His personal cinema delineates the mechanics of transcendence in the rhetoric of abstractionism.

In Re-Entry he successfully synthesizes the Yogic and the cosmological elements in his art for the first time by forcefully abstracting and playing down both of them. The great advance of this film over all of his earlier work consists in the organization of its images into an intentional structure. From an opening of symmetrically ordered dots, moving along the plane of the flat screen and along illusionary lines of depth, the film moves, as if impelled by a directional force, through a fluid series of gaseous colors with a single metaphoric allusion to solar prominences. A second metaphor, the abstraction of a waterfall, focuses the amorphous bands of color into a series of vivid veils lifting to reveal the formation of a spherical vortex which congeals in the final moment into a planet, as if the whole thrust of the film had been towards this one point.