THE TRANSITION FROM the subjective and graphic cinema of the late 1940s to the mythopoeic cinema of the 1960s can be most clearly documented through the films of a number of independent film-makers working in relative isolation in the San Francisco area throughout the 1950s. The collapse of Art in Cinema meant, or at least coincided with, the dissolution of the community of film-makers. Where once films had been completed for the admittedly hostile audience of Art in Cinema at the San Francisco Museum of Fine Arts, now filmmakers protected their isolation like hermits, often refusing to show their films to the few ephemeral groups that sprang up and soon disappeared throughout the country which were sincerely interested in viewing them. Both Harry Smith and Jordan Belson passed through periods of extreme artistic withdrawal, while Larry Jordan and Bruce Conner, significant figures of the subsequent generation, held ambivalent attitudes toward the exhibition and distribution of their films.

The rejection of the social aspects of film production might be seen as part of the Beat ethos which affected in one way or another most of the artists in San Francisco at that time. Yet despite the attitude of the artists, the continuity of an aesthetic tradition spans the decade. The ironic mode of Sidney Peterson and especially James Broughton persists in the work of most of the artists to be discussed in this chapter. Christopher MacLaine, Ron Rice, Bruce Conner, and Robert Nelson (but not Larry Jordan)1 found sufficient space within that ironic tradition to develop their unique styles. A persistent and pervading naiveté absent in the work of their predecessors often vitalizes their cinematic visions. Jordan, who shares a number of formal concerns with the four other film-makers listed above, has moved away from their oscillation between irony and apocalypse.

Christopher MacLaine’s The End (1953) terminated the highly productive period of film-making in San Francisco that had begun with The Potted Psalm. When it was made, the avant-garde movement was already on the way to its first temporary dissolution. The film itself bursts with the rhetoric of finality; it is a deliberately conclusive work. Jordan Belson, who reluctantly photographed the film under MacLaine’s direction, provides one link to the immediate cinematic past. The film leaves no room for the future. It forecasts the destruction of the world by atomic holocaust as the direct sequel to its projection.

The strident language of the narration of The End mixes the prophecy of immediate doom with nostalgia, as if the earth were already gone; descriptions of the film’s characters which insist that these characters can never really be known (the phrase “for reasons we know nothing about” recurs periodically) shift to exhortations to the audience (“Ladies and gentlemen, we have asked you before to insert yourself into the cast. Now we ask you to write this story”). After a brief, frozen image of a mushroom cloud and the ironic opening title, “The End,” the narrator expounds the thesis of the film as we sit in the blackness:

Ladies and Gentlemen, soon we shall meet the cast. Observe them well. See if they are yourselves. And if you find them to be so, then insert yourself into this review; for such it is, a review of things human, a view of things past, a vision of a world no longer in existence, a city among cities gone down in fire; for the world will no longer exist after this day.

In six sections of varying degrees of narrative coherence, we see, and above all hear about, MacLaine’s possessed characters. The first, Walter, has been rejected by his friends. We see him running purposelessly through streets, parks, down flights of stairs, until he is shot, unexpectedly. “For reasons we know nothing about,” the narrator tells us as we see an unknown hand holding a pistol, “just at that moment, another man decided to blow the head off the next person he saw. Our friend was that person.” The scenes of Walter’s running situate themselves in deep perspective, into which he flees or out of which he escapes. Often the empty staircase or street rests on the screen for a few seconds before the actor suddenly enters from an unanticipated direction to pursue his race along the receding line of perspective. Among these in-depth images of flight more enigmatic images are interspersed: street scenes, an arm with taut muscles, a tongue licking an ice-cream cone. Sometimes these shorter, intermediary images bear a direct or indirect relation to the narrative, as when the shadows of dancing people appear on a ceiling as the narrator refers to Walter’s friends: “They went about their games… dancing the dance, and generally forgetting themselves quite admirably.” But more often, these shots anticipate later episodes.

Synecdoche plays a major role in MacLaine’s film, as does ellipsis. The combination of picture and sound at the conclusion of the next episode exemplifies the latter. Here Charles hides in doorways and fearfully makes his way through the city. We are informed that he has just killed his landlady and her daughter, and that he cannot bear to surrender himself to the police. The language of the section’s end is vague: “Then he remembered a place he had often thought of before, and he walked toward it, still enjoying his walk. With his last dime, he removed himself from the threat of red tape and embarrassment, and the slate was already clean.” Two elliptical images clarify this conclusion. First we see Charles pass through a ten-cent turnstile; then the camera pans up to the Golden Gate Bridge. In the combination of picture and sound, both indirect in themselves, we learn that he entered Golden Gate Park and jumped from the bridge.

Next, in presenting the suicide of John, a failed poet turned successful comedian, the film-maker uses several previously mysterious images as metaphors for his narrative. The texture of the metaphors is underlined by the arbitrary mixture of black-and-white shots in a predominantly color film. For instance, the black-and-white head of a sleeping bum is intercut with the color pictures of John’s false friends, who calmly listen to his presuicide speech and applaud it as his best performance. When he leaves the room where, exclusively in close-ups, he had been talking and playing Russian roulette, the picture switches to black-and-white shots of hands playing a piano and a black man dancing. “Someone else took the floor, and John was forgotten. Applause went to the living.” The suicide itself, before a brick wall on which “PRAY” has been painted, cuts from its colored details to these same black-and-white metaphors. The dying man’s collapsing legs are compared to the dancer’s; his dead body to that of the sleeping bum.

In the fourth section, in which Paul, a beautiful young man, decides to give himself to the ugliest of lepers to test the authenticity of love, color and black-and-white intermesh in the action itself. Scenes of Paul by the ocean are a mixture of both film stocks. The relationship between picture and sound had become progressively more indirect in the three earlier episodes, with more and more of the burden of action falling on the words. Here we see Paul wandering by the sea in a garden of statues. He is playing his flute, and he finally walks into a public building; we are told that he will seek passage to a leper colony. But the apocalyptic vision of the opening speech of the film returns when the narrator says, “He will get about as far as the information desk. Then his time will be over, along with ours.”

The process of abstraction on the visual level of the film reaches its apogee in the next episode. Here we are asked to create our own story. “Here is a character.” We see a man in a red shirt, played by the filmmaker, throwing a knife into a board. “Here is the most beautiful music on earth.” We hear Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. “Here are some pictures. What is happening?” The pictures include the facade of a house, a monumental archway, the tensed arm we had often seen before, and more shots of the man and his knife-throwing.

As if unable to tolerate the extremity of ambiguity with which he has confronted us, he begins to make a story for us with echoes of St. Paul on the road to Damascus:

He is a good boy, but somehow we feel he is up to no good. Someone has hurt him. But he has got his ego back, and he will assert himself now. Someone is in the house. Why is he hesitating? Why is he going into the house? No, he will enter and destroy, perhaps? Listen, I know no more about the story than you do, but I know that at this point he was suddenly both blind and dumb, and he takes this as a message from somebody he’d better accept as Master, and walks away from the house and its occupant. Then the world and its music come back to him, and he hums a little song and hears an echo.

The camera frames a cross in the lower left-hand corner of the screen. Then as the Ode to Joy from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is heard, we see puppets and human feet dancing to the music in images that had been proleptic flashes earlier in the film.

The tactic of telling more than one promises to tell or more even than one claims to know had been used earlier in the film toward a more pessimistic end. When the screen went black after the shooting of Walter, the narrator said:

If there were only more time, we could have the story of the unhappy young man who decided to blow Walter’s brains out on his last day. We could follow him through his tribulations in the courthouse, could follow him into solitary confinement; could sit with him while his head was being shaven as he lay whimpering and alone, confused and defeated. We could walk beside him down the gray and sanitary prison corridor toward the mercy we offer to those of us who run amok. We could watch through the window, when he strangles to death trying to catch a breath to say “mama.” Well, we have not enough time for all of the stories. Let us go on. Maybe you will see yourself.

The narrator himself seems to be confused about whether there is not enough time to tell the stories or not enough time for the stories to happen; presumably Walter’s killer will die with all of us in the immediate holocaust. The intentional confusion in the narrative reflects rhythmic alternations and paradoxes of gloom and optimism in the whole of the film. After the conversion in the middle of the fourth episode, the tone of the film suddenly becomes joyous. The final story, a pantomime of unsatisfied desire, does not end bitterly, nor does it have a verbal commentary. We see two figures on the beach—a young man trying to light a match as the waves are lapping over his hands, and a young woman who discovers two pipes which lose their bright colors as soon as she tries to puff on them. Eventually, they see each other and rush together, open-armed. But before they can make contact they fall next to each other writhing in the sand. This fable is resolved by the happy image of a woman riding a white horse in slow motion, intercut with a stream of water hitting a tree. The combination of these two images is the sensual climax of the film. It takes us far from the despair of the opening sections. But now that doom has been finally removed from the foreground of our attention, the atomic bomb explodes, a mushroom cloud rises, and the film ends in a shattering of the title, “The End.”

The extraordinary ambition of The End looks forward to the great achievements of the mythopoeic film. MacLaine came to cinema a little too late to find conviction in the trance film. In The End he made his major statement through a form that could not contain it. Brakhage, during his first stay in San Francisco, saw The End in 1953, before it disappeared from sight for the next ten years. Two years later, perhaps under its influence, he too tried to get beyond the trance film by combining three episodes with a unifying theme in Reflections on Black. Later, after the first Film-Makers’ Cooperative was founded, Brakhage sought out MacLaine and helped put his films into distribution. The formal achievements which make The End a fascinating work—the combination of color and black-and-white, the proleptic use of metaphor, the dialectic of doom and redemption—can be found in a more integrated and full achieved way in Brakhage’s Dog Star Man. Furthermore, in Blue Moses Brakhage refined some of the tactics of direct address and indirect narration which in MacLaine’s original, although they are brilliantly employed, are drowned in the naive urgency of his statement.

After a hiatus of five years, we encounter the next significant achievement in the complex ironic tradition that extends from James Broughton through MacLaine. Bruce Conner made A Movie in 1958 as an extension of his collage sculpture. Aside from the titles (which include a comically long hold on the film-maker’s name), all the images of Conner’s film were culled from old newsreels, documentaries, and fiction films. The natural irony of the collage film, which calls attention to the fact that each element quoted in the new synthesis was once part of another whole, thereby underlining its status as a piece of film, creates a distance between the image depicted and our experience of it. Montage is the mediator of collage. Conner extends that mediated distance by introducing bits of blank film, academy leader, and stray titles (“End of part four” or “The End” near the beginning of the film), as well as reintroducing the title he gave the whole —A Movie—and his name at several points in the middle of the montage.

Unlike MacLaine, Conner is not naive in his vision of doom. Nor are the intellectual rhythms of A Movie, which move between the terrible and the ridiculous, part of a general interior drift, like the desperate but gradual postulation of hope before the finish of The End; Conner deliberately and carefully orchestrated the twists and changes of pace within his film. There is an early sequence which characterizes Conner’s ambivalent manipulation of found images and which demonstrates his visionary stance at the same time. We see a submarine, the movement of whose periscope is intercut with a 1940s nudie film of Marilyn Monroe to suggest that the periscope operator is watching a peep-show. His excited reaction, which must originally have come while sighting an enemy ship, gets a laugh when we translate it to the voyeuristic context. The submarine fires a torpedo, continuing the sexual metaphor for comic effect while adding a hint of terror. The explosion of the torpedo becomes, through montage, an atomic bomb blast; the explosion puts the brake on our laughter with a moment of shock. The shock slowly wears off with the recognition of the visual grace of the mushroom cloud.

A sequence of dangerous stunts, which are comic because of their approach to disaster without actual harm, precedes a sequence of battles which are shocking in their deadly activity. Graceful images which only indirectly suggest the possibility of death (a tightrope walker, descending parachutes) shift the tension after an onslaught of horror. The final sequence of the film, derived from a Cousteau underwater documentary, provides a symbol for ironies and ambiguities upon which the whole collage is organized. Symbolism becomes possible only when the intensity of irony diminishes by becoming a second-degree distancing—the irony of an irony. Within the space of this distancing, a mediating figure represents us, the viewers, within the film. First the camera follows a school of fish. Then we see that this shot had been from the perspective of a scuba diver, our mediator, who, leaving the fish, discovers a sunken ship. Its wreckage has become beautiful through a covering of barnacles. The narrativity and the mystery of this sequence partially derive from the interspersing of pauses of black leader between the shots. Both qualities can enter the film only when the ironic pressure of viewing the individual shots as film garbage suddenly diminishes. In the second-degree distancing, we simultaneously experience the mediation and realize we are watching film collage. The climax of the section creates a metaphor for this disjunction: as the diver descends into the hull of the ship the camera shoots upward at the sun reflected on the surface of the sea.

Conner’s subsequent film, Cosmic Ray (1961), emphasizes the dynamic integration of visual materials over ideological montage. The method of this integration is the imposition of a rhythmical pulse on all shots in the film; the shots include academy leader, end titles, flashes, phrases such as “Head” or “Start,” a nude female dancer—often in superimposition with flashing lights—and bits of old films (advertisements, cartoons, and especially war documentaries). Ray Charles, singing “Tell Me What I Say,” reinforces the tempo of the montage with a rock beat on the soundtrack.

Four fragments of an old Mickey Mouse cartoon frame the climax of the film and provide its ironic center. The first image of Mickey gets a laugh from its sheer incongruity in a film elaborating a metaphor of sex and war. Next we see a huge cannon pointed at Mickey’s head. When it fires, Conner cuts rapidly to anti-aircraft weapons and cannon firing from old documentaries. The phallic nature of all the guns is revealed by their context in the montage and by the illusions of the song text. The barrages of firing are the orgasmic center of the film. When the cartoon comes on again, the cannon suddenly wilts like an exhausted penis as the song calls out for “just one more time.” As it began, Cosmic Ray ends in a welter of leader and flashes.

With his next film, Report 1965), the longest of the three, Conner returned to filmic assemblage (the dancer and the lights of Cosmic Ray had been photographed by him) and to the intense ambivalence of his first film at its privileged moments of secondary distancing. “Irony,” according to Paul de Man, “engenders a temporal sequence of acts of consciousness which is endless.”2 Report begins in the ironical mode by seeming to be simultaneously about the assassination of John Kennedy and about the media’s reportage of it. Like Conner’s first two films, it proceeds, again gradually, toward irony by incorporating collage elements which reflect on the ambiguities of the initial situation.

Repetition, in the form of loop printing, is the dominant trope of the film until its final expansion. Over and over again we see the motorcade, the rifle carried through the police station, an ambulance, Jackie waving as the soundtrack records a news broadcast consecutively from the time of the shooting to the public announcement of death. The discontinuity between narrative and image is the first of the second-degree ironies in the film.

At unexpected points seemingly extraneous material coincides with phrases from the soundtrack. When the newsmen report that the “doors fly open” on Kennedy’s car, Conner cuts to refrigerator doors opening by themselves from a commercial. Mention of the President’s steak dinner coincides with the death of a bull. In irony’s hall of mirrors these are further reflections of the discontinuity which the progress of the film widens and never attempts to repair.

All three of Conner’s films aspire to an apocalyptic vision by engendering in the viewer a state of extreme ambivalence. A Movie and Cosmic Ray achieve this by alternative gestures of attraction (humor, in the first, eroticism in the second) and repulsion (violence in both). The change of pace tactic is not necessary for Report. The film utilizes the emotional matrix of the Kennedy assassination evoked by the newsreel material and above all by the verbal report, while establishing an ever-widening distance from it by means of the looping, the lack of synchronization with the sound, the metaphors, and the linguistic coincidences. It is the one film of the three that does not reverse its tone; it simply reveals itself more and more clearly as what it was at first.

The fables of The End and the ironies of Conner’s first three films share an apocalyptic despair which will diminish, but not die out, in their immediate successors. Both film-makers extended the technical discoveries of their early works in films that were less ambitious and prophetic but no less exquisite. But I shall pass by those works in this schematic chapter in order to clarify the outline of a tradition which has not been defined before. Ron Rice and Robert Nelson, who continued in this line in the sixties, have simplified and elongated MacLaine’s form, the picaresque. Nelson, as if to give his film more cohesion than Rice’s, incorporated strategic elements from Conner’s work.

Ron Rice’s The Flower Thief (1960) is the purest expression of the Beat sensibility in cinema. It portrays the absurd, anarchistic, often infantile adventures of an innocent hero (played by Taylor Mead) while indirectly providing a portrait of San Francisco at the beginning of the sixties. The film-maker began his film with a myth about his working methods: “In the old Hollywood days movie studios would keep a man on the set who, when all other sources of ideas failed (writers, directors), was called upon to ‘cook up’ something for filming. He was called The Wild Man. The Flower Thief has been put together in memory of all dead wild men who died unnoticed in the field of stunt.”3

The finished film seems to preserve the spirit of its making. The uneven lighting, a result of using outdated raw stock, the paratactic montage, which suggests that there was a minimum of editing after the film was shot, and the casual soundtrack create this impression. Although the film has a distinct beginning and end, one feels that the middle could be expanded endlessly. The sequence of its episodes is arbitrary. Rice described the action of the film in a note for its New York premiere at Cinema 16 (the spelling and punctuation are Rice’s):

The central character Taylor Meade a poet moves through a sequence of events. He steals a flower he enters. The Bagle Shop, returns to his home, (an abandoned powerhouse), discovers a man hidden in the cellar with a childs teddy bear. He washes the teddy bear in the bathroom then discovers the room full of people, and is chased. He destroys a bullshitting radio. The Beatniks carry on with spontaneous antics, reinacting the crucifistion, and changing the graphic meaning to the flag plainting at Iwo Jima. Telephone, pits, beats in lockers making love; a woman climbing monkey bars to reach her lover.

The poet is searching, but he never finds love. The ending of the film suggests he finds something, but we do not know for he disappears into the sea. The audience must discover the “message” if one is demanded. Elements of Franz Kafka and Russian Humanism are there.4

Occasionally the soundtrack veers from random accompaniment to crude poetry: “The time man has spent in his brothers’ prisons can now be measured in light years”; “Christ on opium, marijuana used in the past. … Peruvian civilization based on cocaine, America on coca-cola.” Or to irony (an excerpt from Peter and the Wolf is heard while Mead picks flowers, Alexander Nevsky while he moves among firetrucks and tries to direct traffic).

Ron Rice’s films contain mythic elements, but his heroes are neither the somnambulistic dreamers of the trance film in search of sexual identity nor the Romantic questers of the mythic cinema. They are complex mediators who move between realism and allegory within a single film in a chain of discontinuous roles. At times the poet of The Flower Thief becomes the impersonal victim of society, as when he is tried in a cardboard court, upon which is written Justice, for urinating in the park. But Rice also has an eye for the poetic particulars of naturalism: the poet’s feeding his cat in the powerhouse by candlelight and a brief scene of a couple taking a shower are high points in his film.

Rice would have made another episodic film right after The Flower Thief; he even attempted two, one called The Dancing Master and another with his close friend, the painter and film-maker Jerry Joffen. But he lost interest in them. According to a story he told in 1962, Senseless, finished that year, came out of a film he had planned to make of Eric Nord’s island. Nord had been an actor in The Flower Thief and the proprietor of the Gaslight Cafe in Venice, California, who, as the story goes, purchased an island from the Mexican government with the modest intention of establishing a Utopia. Unfortunately he neglected to ascertain whether or not there was fresh water on his island. There was not, of course. So he and his pilgrims set up camp with army surplus parachutes for tents on the shores of Baja, California. When Rice and some other settlers arrived, Nord and his pioneers were gone. Unfurled lonely parachutes rocked with the breezes. Whether The Dancing Master was to be the Utopian film of Nord’s island or whether Rice had planned to make an entirely different film on that terrestrial paradise, I do not know; nor does it matter much, since the nucleus of his projected film was gone either way. He had filmed the trip down to the camp and the deserted parachutes and whatever of the Mexican landscape interested him along the way. He and his friends stayed in Mexico, filming one thing and another as tentative films occurred to them.

When Rice got to New York he pooled the various episodes and studies together. Since there would be no plot, nor even the continuity of a single mediator, he pretended the film had been written by Jonas Mekas, who at that time was devoting many of his columns in the Village Voice to promoting the plotless film. On the screen he gives Mekas credit for “the script.” It is a natural irony of circumstances that the resulting film of Rice’s potpourri, Senseless, is by far the most carefully organized, formal film he left. (He died of pneumonia while in Mexico at the end of 1964.) It is a film thematically constructed around a trip to and from Mexico, with recurrent images of cars and trains (they actually sold their car illegally and slipped out of the country on the train) and much pot-smoking. The rhythmic intercutting of scenes gives the film its cohesion.

Back in New York, his hometown, Rice brought together Taylor Mead and Winifred Bryan, a colossal black woman, to make The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man. He did not live to complete the editing. He was constantly cutting it and adding new sequences. Bryan plays an alcoholic odalisque, and Mead much the same type as in the earlier film but now with overtones of a scientist. In the rough cut which Rice often screened to raise money to complete the film, there were two scenes of extended parody: a spoof on Hamlet with Jack Smith as the Prince, and a less direct take-off on Gregory Markopoulos’ Twice a Man, which had been completed while The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man was in production. In his tentative version Rice ended his film where Markopoulos’ began, on the Staten Island ferry. According to Taylor Mead’s notes on the production, the Hamlet spoof was to have been preceded by an excerpt from the Olivier film version, and another film quotation from Welles’s The Trial was to have introduced still another satire.

The combination and intercutting of characters brought The Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man a step closer to the synthetic process of the mythic film, but at the same time the ironic gap between the actors as they appear on the screen and the roles they assume widened. In this enlarged space the film moves between epiphany and parody. The divorce between the subjective center of the film and the various forms it takes is reflected in Taylor Mead’s encounter with many objects. Attracted to household products by advertisements, he does not understand their functions; so he will rub a box of cereal over his clothes or, with Chaplinesque inventiveness, insert the prongs of an electric plug in his nose in the hope of getting high. The subjectivity of the mythopoeic protagonist is grounded in his privileged contact with the primal rhythms and rituals of the universe, even when they defeat him. Rice concentrates on describing the estrangement of his heroes in terms of realities. Although he may suggest a deeper, alternative core of existence for the protagonist of The Flower Thief, he is more reluctant to do so for the figures of his later picaresque. When relieved of the immediate estrangement of the city, they manifest their subjectivity ironically: they engage in parodies.

A late example of the type of film being discussed is Robert Nelson’s The Great Blondino (1967). In it, the picaresque and the mythic overlap, and irony, which is prevalent in many aspects of the film, ceases to play a structural role. In the previous chapters we have seen the applicability of Harold Bloom’s analysis of Romantic mythopoeia to several major films of the American avant-garde, whose “myth, quite simply, is myth: the process of its making, and the inevitability of its defeat.” Here the same pattern can be seen with somewhat diminished intensity. Blondino, the central character, a tightrope walker, wanders through the San Francisco townscape pursued by a detective from “the committee.” In his gray clown suit, the alienated and naïve protagonist is the immediate heir of the flower thief and of MacLaine’s figures, and more distantly but even more closely a reincarnation of the caged artist in pursuit of his eye in Peterson’s The Cage. This connection, of which Nelson and his collaborator, the painter William Wiley, were unaware, is never so apparent as when Blondino pushes his ever-present wheelbarrow through crowded streets wearing a blindfold.

One debt to earlier films has been acknowledged by Nelson repeatedly: since his second film, Confessions of a Black Mother Succuba (1965), he has recognized his debt to Bruce Conner. From the very opening of The Great Blondino, his sixth film, the synthesis of Conner and Rice is evident. A white knight from a television commercial is transformed by a magical wand, also from a commercial, into the protagonist of the film, “a misfit, out of step,” in the ironical language of one of the film’s minor characters.

Until its last minutes the film has no narrative order. Scenes, which are too brief and dispersed to be called episodes, change and recur in rhythmic waves according to the logic of dream association. Several explicit scenes of the hero sleeping and even more references to dreams in the form of sawing wood or a line of “z’s” flashing across the image can be meant either to frame a central portion of the dream or to implicate the entire film in a dream vision. At times, Blondino lapses into the passivity of a somnambulist from the trance film tradition. Then he mediates, as the dreamer, the disorienting encounter with collaged newsreels that the film-maker, again developing upon Conner’s work, has built into the film.

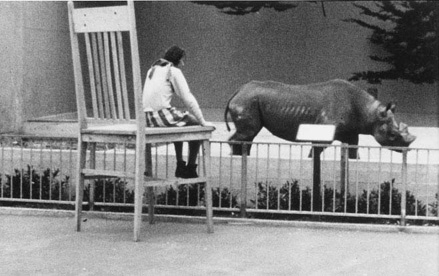

Nelson suppresses the ironic presence of the quotations from newsreels and old films by meticulously integrating them into the spatial logic of his photographed scenes. Unlike Conner’s collages, these images are not allowed to burst into the viewer’s consciousness as affirmations of the materiality of the film as film. They are part of a strategy of careful disorientation which includes radical changes of scale. For instance, by superimposition Blondino appears to dance in a frying pan, and later in one of the most memorable images in the film he climbs on a gigantic chair several times taller than a man, actually built for this effect, to watch a rhinoceros pacing in the distance. The effect of this latter disorientation is all the greater because the placement of the chair in the foreground of the shot makes it look optically rather than actually enlarged for a few seconds before Blondino enters the frame to provide a measure of camparison.

Conflict of scale in Robert Nelson’s The Great Blondino.

At the very end of the film there is a narrative attended by an ironical undercurrent reflexively attesting to the cinematic illusion. First the detective makes a statement of his function in the film: “When the committee heard about this fellow, we were quite sure that his operations were not in the national interest.” Up to that point, his role had only been suggested by his costume, mimicry, and a musical motif underlining his periodic appearances. Following the detective’s speech, Blondino attempts his fatal rope-walking. This is the climax of the film, but Nelson distances from it by cutting from the actor to his image on the tightrope, first projected on the screen of a movie theater, then on television. When he falls, subjective drama and the affirmation of material fuse: his descent is indicated by a fast montage of flashes, flares, and numbers from academy leader. Then, by metaphorical extension, his disaster is prolonged in a quotation from a science fiction film in which a giant octopus captures a man.

In the final ambiguous moment of the film, Blondino walks again on solid ground, pushing the wheelbarrow, in an image of prismatic distortion. This resurrection, like the quoted images preceding it, is nostalgic. In a note for the Experimental Film Competition of Knokke-le-Zoute at the end of 1967, the film-makers offered the following statement:

Robert Nelson’s Bleu Shut: the name of a boat, the clock, over a loop-printed image of a barking dog.

This is a long film that uses no specific narrative development. Its coherence depends upon deeper non-verbal sensibilities. The great Blondino is a figurative allusion to the tightrope walker Blondin, who gained international fame in the 19th Century by walking many times across Niagara Falls on a tightrope. The film speaks about the level of risk at which we live and of the foolishness and beauty of our lives at the edge, where we confront that risk.5

Rather than speak of risk, the film longs for one. Its version of the process and defeat of mythopoeia is bound up with a temporal predicament of which the film-maker hardly seems aware. In this very controlled and well-integrated film, what is out of control and cannot be integrated is its elegiac mood, which ultimately undermines its mythopoeia.

Nelson’s most sustained achievement so far, Bleu Shut (1970), found for itself a new form which could contain and derive energy from the contradictory tendencies of his fourteen earlier films. Bleu Shut is a prime example of the participatory film, a form which emerged at the end of the 1960s out of extensions of the structural film. If we survey these forms diachronically, it would seem that the great unacknowledged aspiration of the American avant-garde cinema has been the mimesis of the human mind in a cinematic structure. Beginning with an attempt to translate dreams and other revelations of the personal unconscious in trance film, through the imitation of the act of seeing in the lyric film and the collective unconscious in the mythopoeic film, this cinema attempted to define consciousness and the imagination. Its latest formal constructions have approached the form of meditation—the structural film—in order to evoke more directly states of consciousness and reflexes of the imagination in the viewer. The participatory films follow the direction established by the structural cinema in finding corollaries for the conscious mind.

In Bleu Shut Nelson proposed film-viewing as a testing experience. At the same time George Landow was making Institutional Quality from the same premise, while Hollis Frampton was presenting montage as a logical function and cinematic construction in general as a system of thought in his film Zorns Lemma. Each of these film-makers came to this point of formal evolution following clues in their own earlier works rather than from mutual interaction or from a common source of inspiration. For both Landow and Frampton that immediate past entailed an intense involvement with the structural film. Nelson’s one structural film, The Awful Backlash (1967), a single shot for fourteen minutes of a hand untangling the snarled line of a fishing reel, does not represent a crucial moment in his evolution. For him the fixed camera was one of many contingent strategies explored in several short films made at the same time as The Great Blondino, which later would inform the synthesis of Bleu Shut.

In The Great Blondino the film-maker attempted to unite footage he collected from various sources with his own photography through a mythic narrative that could bridge both. In Bleu Shut he invented a form which would be capable of holding together many different kinds of film while maintaining their integrity as home movies, advertisements, quotations, etc. In Nelson’s inflection of the participatory form, the very question of synthesizing the materials of the film is handed directly to the viewer. In the ironic structure he provides, all images share a relationship to oneminute subsections of the film. Screen time is affirmed in two ways. A small transparent clock appears in the upper right-hand corner of the screen, measuring the minutes and seconds throughout the film. That measurement is reinforced by a number which flashes briefly on the screen at the beginning of each new minute.

The film is ironically subtitled “(30 minutes)” and at the beginning a woman’s voice tells us, “This film will be exactly thirty minutes long.” But it is not. At the end of the half hour the cards indicating the minutes no longer appear, but the film continues for another four or five minutes, according to its own clock, as its maker, in negative, tests the sound system in preparation for a speech about the nature of cinema, which we never hear. The failure of the film to terminate at the exact instant predicted surprises us because all of the other promises heard at the beginning were precisely fulfilled. The woman’s speech describes the future of the film:

I’m now off-stage where Bob and Bill can’t hear me. This is how its gonna be: This film is exactly thirty minutes long. The little clock in the upper right and corner tells the exact amount of time that has elapsed from the beginning and the amount of time left….

At 5 minutes, 35 seconds comes the Johnny Mars Band.

At 11:15, weiners.

At 21:05, pornography.

At 23:30, a duet.

Watch the clock.

What she does not tell us is that most of the film’s time will be occupied by a guessing game. For an entire minute a color photograph of a boat will appear on the screen with six possible names printed over it. The first time the choices are: Bodo, Moki-Moki, Heaven Sabuv, Vegas Vamp, Big Boy, and Sea Dancer. Offscreen, we hear two men, Bob and Bill (the filmmaker and William Wiley), deliberating on which name they will pick. At the end of the minute they each make a choice; then the woman tells them the answer. This game is repeated eleven times at intervals of one minute. More often than not, both men guess wrong. Naturally the viewer of the film is drawn into the guessing game because of its duration, repetition, and the possibility of measuring his luck against that of the two guessers within the film.

In the minute-long intervals between the pictures of the boats, or in parts of those minutes, various collected and photographed images appear which invoke different problems in the perception of film. The naked filmmaker, crawling through a cubicle of mirrors, creates a confusion of the actual with the reflected body. The image of a steaming hot-dog proclaims itself as a loop only when the viewer begins to perceive the repetitious pattern of a barely perceptible puff of steam, and then without any indication of a transition, the looping ends, and a fork severs the hot dog. A more obvious loop of a dog barking takes on an ambiguous dimension by the irregular alternation between silence and synchronized sound. The appearance of the frame line and surface dirt points out the filmic objectivity of an old pornographic film incorporated within Bleu Shut. Another allusion to the conventions of cinema is a Hawaiian number out of an old musical.

Each of these inserts, which are for the most part found objects, functions independently. There is no interweaving of imagery nor narrative continuity. Each elongates and divides the parts of the guessing game like advertising interrupting a television quiz show, but, unlike advertisements, they do not have a distinctly negative relation to the game. They are of equal importance, simply its reverse face. In fact, some of the intentional energy of the game carries over to the inserts, as if the audience were being called on to solve perceptual puzzles, to interpret them, and above all to construct a unity out of their diversity. Bleu Shut reverses the thrust of The Great Blondino. By fracturing the possible unities between found objects and filmed scenes and suggesting a field of cinematic perception without a center—or at best with a problematic center—it demythologizes its own ironies and at the very end almost throws the film-maker outside his own film (he does not fit within its “30 minutes”). The Great Blondino, on the other hand, had a mythic center where the ironies of the materials could mesh with the ironies of the narrative.

The movement between works which establish a tentative center and those which disperse or put into question their centers, observed in these two films by Nelson, characterizes all of the films I have grouped in this chapter. At times the desire for a central organization has been satisfied by a loose, picaresque development substituting for a mythic core, and just as often (but not in the case of Bleu Shut) the dispersed structure has been a metaphor for the apocalyptic intention of the film. Different dynamics and dimensions of irony in the films of MacLaine, Conner, Rice, and Nelson have intensified the formal alternations within individual films and within whole filmographies. These film-makers have been grouped here not to suggest that they form a school or exhibit a regional sensibility. Far from it. Bruce Conner and Ron Rice were very independent figures who began working in film in the late 1950s when the avant-garde cinema was at its least cohesive. They simply share in their works certain patterns of responding to the void. MacLaine was another isolated artist who came at the very end of a strong movement, whose major film pointed chaotically toward the forms of the later 1950s. Nelson’s work, on the other hand, marks the end of that period. In his hand the picaresque and the centerless film becomes a deliberate strategy for making works which respond to the new cohesion of the national avant-garde cinema of the 1960s. An enclosed picture of the historical moment we have been considering calls for a discussion of the films of Larry Jordan, even though the ironic factor, a common denominator of those I have been discussing, plays a minimal role in both his films of photographed actuality and his animated collages. His materials, subjects, and forms coincide and envision a continuous world where strong or fragile moods are never ruptured. Yet despite these thematic differences, Jordan’s isolation and his artistic responses to the situation of the l950s draw him into consideration with the men I have been discussing.

Larry Jordan’s formative period as a film-maker extends throughout the 1950s. He began to make films at approximately the same time as Stan Brakhage, with whom he went to high school in Denver. Jordan appears in Brakhage’s Destistfilm (1953) and Brakhage in his Trumpit (1956), both psycho-dramas. Brakhage’s approach to film-making and the energy with which he pursued it was unique in the 1950s. He moved between Colorado, New York, and San Francisco, often in pursuit of the vanished centers of late-1940s film-making. He continued making and extending the form of the trance film until he forged the lyric cinema described in chapter 6. He not only avoided the kind of crisis most of his colleagues faced at that, time, but he even managed to keep up a frail connection between the dispersed and sometimes retired film-makers he sought out in his crosscontinental movements.

Jordan failed where Brakhage succeeded in finding a convincing form within the trance film. He matured as an artist and found his authentic voice in film by gradually withdrawing from the role of the film-maker that the previous generation of avant-gardists had established as a norm. As he lost interest in reconstituting the community of film-makers and in the politics of distribution and promotion toward the late 1950s, the distinction between a finished film and a work-in-progress seems to have dissolved for him. In its place came a gradual involvement with the possibility of cinema to testify to the processes of its own making and with films designed to celebrate a particular occasion. When he tentatively reemerged as a publicly exhibiting film-maker at the apogee of the revived interest in the avant-garde film around 1963, he had produced a substantial body of work, radically different from his early psycho-dramas, to which it is difficult to assign dates.

In those few years Jordan had become one of the few film-makers to develop confidence in the artistic validity of a less formal, more spontaneous cinema. Elsewhere in America, in similar isolation, a few other filmmakers had come to the same position, as we shall see in the next chapter. Later, when Jordan briefly released the films he had been making without thought of public exhibition, he put them in groups, usually combining animations with actualities: for example, 3 Moving Fresco Films contained Enid’s Idyll and Portrait of Sharon, both animations, and Hymn in Praise of the Sun, a series of “cine-portraits.” Among his films are animated collages, pixilated actualities, portraits, superimposition films, and a handpainted film. Some were edited within the camera. He described an aspect of his working process in Film Culture:

[Making Pink Swine] I got very carried away with object animation and combining layout animation and object animation. I was moving objects at all different rates; I was setting the camera; I wasn’t hand-holding it; I was using it just like a musical instrument, like playing a saxophone, pushing the button on the camera and moving the objects in rhythm. All those films [in Petite Suite] were improvised; they’re virtually as they came out of the camera.… I didn’t want everything to move at one particular rhythm; it all depended on what the subject material was. But I wasn’t planning it. I was just letting my mind go and see what could be done in 100 ft. [i.e., about three minutes of film]. I liked the 100 foot form. The film was done before you had time to change cameras; I don’t remember whether it was one sitting or not, but it wouldn’t have been more than two days. You can’t do a dance, one dance, in two different days, and these films are essentially dances, you know.6

The oscillation between predetermined and spontaneous films set in motion a spiralling intensity in the investigation of the oneiric and metaphysical dimensions of Jordan’s cinema. Curiously unlike MacLaine, Conner, Rice, and Nelson, that intensity paralleled a growing frailty, so that the extraordinary series of works which represent the first climax of Jordan’s career, Duo Concertantes (1962-1964), Hamfat Asar (1965), The Old House, Passing (1966), Gymnopedies (1968), and Our Lady of the Sphere (1969)—all animations of Victorian engravings except The Old House Passing—occupies an exquisite space and time where reverie and dream meet, delicately poised between nostalgia and terror.

Duo Concertantes has two parts, The Centennial Exposition and Patricia Gives Birth to a Dream by the Doorway. Both Patricia and Hamfat Asar, the two most spectacular of his animations, operate against the backdrop of a fixed scene. In the former, it is a back view of a young lady framed in a doorway looking out upon woods and a lake; in the latter, Jordan uses an engraving of a seacoast with cliffs. Time and a change of culture have given a surrealistic and nostalgic aura to Victorian woodcuts, as Max Ernst and several collagists between him and Jordan have known for five decades. Where Ernst slammed together radically incongruent images from such found material and thereby released the terrors of monstrosities and the sensual depth of inconceivable landscapes, Jordan has chosen to refine their delicacy and to push his images almost to the point of evanescence—a limit represented in several collages by the reductive metaphor of a film within a collage-film flickering with pure imageless light.

The background picture of Patricia returns us to the moment when the American avant-garde film found its first image of interiority, that is, to the image of Maya Deren pressing her hands against the window in Meshes of the Afternoon to gaze inwardly upon a double of herself chasing the mirror-faced figure. The doorway in which Patricia stands is both the port of exchange and the barrier between the inner and outer worlds, as Maya Deren’s window and before her Mallarmé’s “Fenêtre” had been. Outside, tiny images descend from the top of the screen. First an elephant comes down and slowly sinks out of the bottom, but in his downward course he deposits an object which hovers on the horizon of the lake. The discontinuous power of that horizon line to hold objects from falling down the flat screen provides the film with a frail but finely conceived tension between two illusionary gravities, that of the actual theater in which we see the film where objects must fall from the top of the screen through the bottom, as if to land on the floor under our feet, and the represented gravity line, the horizon, within the engraving. The manifestation of objects and their movements within the film enumerate the variations possible between these two centers of gravity.

In the incessant materialization and disappearance offscreen or suddenly vanishing by moving of objects and creatures, the usual way of defeating the gravitational forces is by growing wings and flying offscreen, at the edges. The inside/outside distinction and its evaporation generates the central apperceptive metaphor of the film. A picture stand appears on the horizon. On its white screen a black-and-white flicker occurs; slides appear in sequence; then a bird flaps its wings in an evocation of the origins of cinema. It flies off the screen and into the illusory landscape surrounding it. In the final extensions of this trope, a swarm of bees appears on the little screen; some disappear as soon as they overreach its frame, but others escape into the landscape. These bees come inward, past the unmoving woman, and are lost within the house. To commemorate this triumph of the imagination, a star falls splashing into the lake, an egg takes wing, and Larry Jordan’s most delicate film ends.

In Hamfat Asar (whose title joins a made-up word from Jordan’s household, “Hamfat,” with an archaic name of Osiris, the Egyptian underworld god) the film-maker generates tensions similar to that of the discontinuous horizon in the earlier film by stretching a tightrope across his seascape. A figure on stilts crosses it repeatedly while creatures and objects float by in the background, manifest themselves, and obscure the foreground or cross and perch upon the tightrope. In the course of his crossings, he will become a bird, a train, a floating balloon.

Once, the entire picture bursts into actual flames. Later a star explodes, first whitening, then blackening out the whole image. When the landscape reappears, the tightrope is gone, but the man on stilts starts to cross, successfully, as if it were there. He does not complete the passage until, at the end of the film, a cloud floats by on which he can stand.

The Centennial Exposition, Gymnopedies, and Our Lady of the Sphere use with increasing complexity numerous backdrops which are connected by the continuous movement of a foreground figure from one to the next, although that figure tends to be undergoing its own continual metamorphosis. In Gymnopedies he tinted the entire film a pastel blue, and in Our Lady of the Sphere several solid screen colors and occasionally split-screen two-color moments have a structural function in the complex animation. He alternates zooming motions, accenting first movements on the left side of the image, then on the right, and he uses Cubist superimpositions of a single figure out of phase with itself to represent new perspectives of space and depth in animation. He also uses montage to parallel interior scenes with those taking place on a moonscape. At its most complex, in a scene of circus acrobats turning into flashing stars, he employs hand-held backdrops and three different colors in superimposition with counterpointed movements on the different levels. In the middle of the film he shows a horse staring at an easel which becomes a film within a film, flickering and breaking the limits of its frame as had happened in Patricia. The elaborate techniques of Our Lady of the Sphere permit Jordan to break through the conventions of continuity he had created and then thoroughly explored in his earlier collage films. Yet he had to sacrifice the crucial tension of the slow and delicately elaborated imagery to gain the complex dynamics of the later film.

The flickering film-within-a-film: Larry Jordan’s Patricia Gives Birth to a Dream by the Doorway.

In The Old House, Passing, he resurrected a setting from the trance film, the mysterious house, to construct a radically elliptical narrative that attains a height of fragility comparable to the best of his animated films. According to the film-maker:

It is a ghost-film wherein the central mood revolves around a plot, rather than moving straight along a plot line. Mood predominates over plot, but plot is always there before the eye, as well as behind and to the side of it. Within the meshes of the fabric an older woman has lost a man (husband?) and a child thru a mysterious accident or disappearance. Elements (a young man, woman and child) are drawn into her which release her from the past and the dark mysteries of the huge old house and the night-walking spirit of the departed soul.7

In this film Jordan translated the strategies of his animated films into events in actual space and time. By using prolepsis, repetition, and shifting perspective he keeps the relatively simple narrative in an elusive state of development throughout the film, as if he were extending the conventional opening of a mystery film into a total structure. The full disclosure of the narrative is suspended, hinted at, but never achieved. The situations of the film—a couple and their child spending a night in an old house and subsequently exploring it; the old woman who lives there watching them; the ghost of her dead husband watching her and them—give rise to an ambivalence in which the distinction between observation and fantasy breaks down, and past and present interpenetrate. The reveries of Patricia Gives Birth to a Dream by the Doorway have their narrative equivalents in the slow, formally composed, chiaroscuro images of shifting and overlapping explorations, discoveries, and encounters.

Rather than reach a climax, the film simply shifts to a scene of exorcism. The family visits a cemetery, where we assume the ghost is buried, and in an act of deflating the mood of mystery, they blow soap bubbles through the graveyard and leave. But even that release is framed by the perspective of the ghost who watches their departure.

The Old House, Passing makes the temporality which is at the heart of all the films discussed in this chapter thematic. These film-makers of the fifties and sixties were perhaps the first to explore the fundamental disparity between the nostalgia of the photographic image and the “nowness” of projected film. Once this chasm began to open for them, they created an apocalyptic and a picaresque form that commented ironically on that temporality. It also sought to bridge that chasm with an ontology of terror (MacLaine’s desperate men, Conner’s disasters, the flower thief’s paranoia, Blondino’s tightrope walk, and the haunting of The Old House, Passing) which reaches its most diminished point in the experience of harmless risk (the games of Bleu Shut). Risk and terror (and in Jordan’s case the threshold between terror and wonder) provide the healing moment in which cinematic time and the time of its perception would coincide.

In New York during the same years other film-makers were encountering the same temporal paradox, which they took as their theme in different personal ways, creating myths of recovered innocence and its failure.