tweleve

Structural Film

THE MOST SIGNIFICANT development in the American avant-garde cinema since the trend toward mythopoeic forms in the early 1960s was the emergence and development of what I have called the structural film.1 The pattern which operated within the work of Maya Deren was echoed, as I have shown, in the entire thrust of the American avant-garde cinema between the late forties and the midsixties; on the simplest level it was a movement toward increased cinematic complexity. Film-makers such as Gregory Markopoulos, Sidney Peterson, Kenneth Anger, Stan Brakhage, and Peter Kubelka, to name a few of the most conspicuous, moved toward more condensed and more complex forms.

Since the mid-sixties a number of filmmakers have emerged whose approach is quite different, although dialectically related to the sensibility of their predecessors. Michael Snow, George Landow, Hollis Frampton, Paul Sharits, Tony Conrad, Ernie Gehr, and Joyce Weiland have produced a number of remarkable films apparently in the opposite direction of that formal thrust. Theirs is a cinema of structure in which the shape of the whole film is predetermined and simplified, and it is that shape which is the primal impression of the film.

The structural film insists on its shape, and what content it has is minimal and subsidiary to the outline. Four characteristics of the structural film are its fixed camera position (fixed frame from the viewer’s perspective), the flicker effect, loop printing, and rephotography off the screen. Very seldom will one find all four characteristics in a single film, and there are structural films which modify these usual elements.

What then would be the difference between the lyrical film I have described and the structural film? What would be their relationship? The lyrical film too replaces the mediator with the increased presence of the camera. We see what the film-maker sees; the reactions of the camera and the montage reveal his responses to his vision. In the opening sequence of Hammid and Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon, we found the roots of firstperson cinematic consciousness. They filmed the first approach and exploration of the house from the point of view of the puzzled participant. But they immediately qualified—or mediated—that forceful opening by showing the figure of the protagonist in subsequent variations. In creating the lyrical film, Stan Brakhage accepted the limitations of that opening sequence as the basis for a new form. Out of the optical field and metaphors of the body’s movement in the rocking gestures of the camera, he affirmed the film-maker as the lyrical first person. Without that achievement and its subsequent evolution, it would be difficult to imagine the flourishing of the structural film.

The four techniques are the more obvious among many subtle changes from the lyrical film in an attempt to divorce the cinematic metaphor of consciousness from that of eyesight and body movement, or at least to diminish these categories from the predominance they have in Brakhage’s films and theory. In Brakhage’s art, perception is a special condition of vision, most often represented as an interruption of the retinal continuity (e.g., the white flashes of the early lyric films, the conclusion of Dog Star Man). In the structural cinema, however, apperceptive strategies come to the fore. It is cinema of the mind rather than the eye. It might at first seem that the most significant precursor of the structural film was Brakhage. But that is inaccurate. The achievements of Kubelka and Breer and before them the early masters of the graphic film did as much to inform this development. The structural film is in part a synthesis of the formalistic graphic film and the Romantic lyrical film. But this description is historically incomplete.

By the mid-1960s the contributions of the lyrical and graphic cinema had been totally assimilated into avant-garde film-making. They were part of the vocabulary a young film-maker acquired at the screenings of the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque or the Canyon Cinema Cooperative. They were in the air. The new film-makers were not responding to these forms dialectically, because they situated themselves within them, no matter which films they preferred and which they rejected.

The major precursor of the structural film was not Brakhage, or Kubelka, or Breer. He was Andy Warhol. Warhol came to the avant-garde cinema in a way no one else had. He was at the height of his success in the most lucrative of American arts—painting. He was a fully developed artist in one medium, and he entered another, not as a dabbler, but with a total commitment. He immediately began to produce major cinema. For years he sustained that production with undiminished intensity, creating in that time as many major films as any of his contemporaries had in a lifetime; then, after completing The Chelsea Girls (1966), he quickly faded as a significant film-maker.

Warhol began to take an interest in the avant-garde film in 1963 when it was at the height of the mythic stage. He quickly made himself familiar with the latest works of Brakhage, Markopoulos, Anger, and especially Jack Smith, who had a direct influence on him. On one level at least—and that is the only level of importance to us—Warhol turned his genius for parody and reduction against the American avant-garde film itself. The first film that he seriously engaged himself in was a monumental inversion of the dream tradition within the avant-garde film. His Sleep was no trance film or mythic dream but six hours of a man sleeping. (It was to have been eight hours long, but something went wrong.) At the same time, he exploded the myth of compression and the myth of the film-maker. Theorists such as Brakhage and Kubelka expounded the law that a film must not waste a frame and that a single film-maker must control all the functions of the creation. Warhol made the profligacy of footage the central fact of all of his early films, and he advertised his indifference to direction, photography, and lighting. He simply turned the camera on and walked away. In short, the set of concerns which I have associated with the Romantic heritage of the American avant-garde film were the object of Warhol’s fierce indifference.

Stephen Koch has something to say on this subject:

The Duchampian game in which objects are aestheticized merely by turning to them with a certain glint in your eye does have continuing value, though not as the comical anti-art polemic so often ascribed to it …

It is possible to understand this rather specialized aesthetic experience as a metaphor, in consciousness, for the perception of things at large, in which the unlike things compared and fused are the self and the world …. It is a major modernist procedure for creating metaphors, and an antiromantic one, since it locates the world of art’s richness not in Baudelaire’s “Elsewhere” but in the here and now. At least almost.

Warhol goes further. He wants to be transformed into an object himself, quite explicitly wants to remove himself from the dangerous, anxiety-ridden world of human action and interaction, to wrap himself in the serene fullness of the functionless aesthetic sphere.2

Warhol defines his art “anti-romantically.” Pop art, especially as he practiced it, was a repudiation of the processes, theories, and myths of Abstract Expressionism, a Romantic school. Warhol’s earliest films showed how similar most other avant-garde films were and, to those looking closely, how Romantic. Yet whether or not the anti-Romantic stance can escape the dialectics of Romanticism is an open question. Koch seems to think it cannot:

Transforming himself into the object celebrity, Warhol has made a commitment to the Baudelairean “resolution not to be moved”—an effort to ensconce himself in the aesthetic realm’s transparent placenta, removed from the violence and emotions of the world’s time and space. So Warhol turns out to be a romantic after all.3

The roots of three of the four defining characteristics of the structural film can be found in Warhol’s early works. He made famous the fixedframe in Sleep (1963), in which a half dozen shots are seen for over six hours. In order to attain that elongation, he used both loop printing of whole one-hundred-foot takes (2¾ minutes) and, in the end, the freezing of a still image of the sleeper’s head. That freeze process emphasizes the grain and flattens the image precisely as rephotography off the screen does. The films he made immediately afterwards cling even more fiercely to the single unbudging perspective: Eat (1963), forty-five minutes of the eating of a mushroom; Empire (1964), eight continuous hours of the Empire State Building through the night into dawn; Harlot (1965), a seventy-minute tableau vivant with offscreen commentary; Beauty #2 (1965), a bed scene with off- and on-screen speakers lasting seventy minutes. Soon afterwards, he developed the fixed-tripod technique of reconciling stasis to camera movement. In Poor Little Rich Girl: Party Sequence (1965), Hedy (1966), and The Chelsea Girls (1966) he utilized camera movements, especially the zoom, from the pivot of an unmoving tripod without stopping the camera until the long roll had run out. Yet Warhol as a pop artist is spiritually at the opposite pole from the structural film-makers. His fixed camera was at first an outrage, later an irony, until the content of his films became so compelling to him that he abandoned the fixed camera for a species of in-the-camera editing. In the work of Michael Snow and Ernie Gehr, the camera is fixed in a mystical contemplation of a portion of space. Spiritually the distance between these poles cannot be reconciled.

In his close analysis of Warhol’s early work, Koch views these films with the kind of intensity and perspective that the structural film-makers brought to them. He sees in them the framework of an apperceptive cinema. In the end of Haircut (1963), in which someone in a barber’s chair, after a long stare into the camera, breaks into unheard laughter as the final roll of film flares up in whiteness, he sees “the cinematic drama of the gaze, reaching its final and reflexive development”:

The moment is a gently felt turn of self-consciousness suggesting the gentlest of put-ons—a put-on not in the sense of artistic fraud but that implied by a kind of Prosperolike cadenza (if I may compare great to small), a breaking of the spell. With it we realize that, like all the other early films, Haircut is about the hypnotic nature of the gaze itself, about the power of the artist over it.4

Koch sees that beyond the obvious aggressions and ironies of the early Warhol films—and perhaps because of them—there is a conscious ontology of the viewing experience. What the critic does not say is that these apperceptive mechanisms are latent or passive in Warhol’s work. To the film-makers who first encountered these films the mid-sixties (those who were not threatened by them), these latent mechanisms must have suggested other conscious and deliberate extensions: that is, Warhol must have inspired, by opening up and leaving unclaimed so much ontological territory, a cinema actively engaged in generating metaphors for the viewing or rather the perceiving, experience.

Thus the structural film is not simply an outgrowth of the lyric. It is an attempt to answer Warhol’s attack by converting his tactics into the tropes of the response. To the catalogue of the spatial strategies of the structural film must be added the temporal gift from Warhol—duration. He was the first film-maker to try to make films which would outlast a viewer’s initial state of perception. By sheer dint of waiting, the persistent viewer would alter his experience before the sameness of the cinematic image. Brakhage had made a very long film in The Art of Vision, but he was apologetic about its four hours; it had to be that long and not a minute longer, he would claim, to say what it had to say. Ken Jacobs had been bolder or more honest in describing the endless and perpetually disintegrating experience of his projected Star Spangled to Death. But that too would have been a perversely orchestrated experience from beginning to end.

Warhol broke the most severe theoretical taboo when he made films that challenged the viewer’s ability to endure emptiness or sameness. He even insisted that each silent film be shown at 16 frames per second although it was shot at 24. The duration of his films was one of slightly slowed motion. The great challenge, then, of the structural film became how to orchestrate duration; how to permit the wandering attention that triggered ontological awareness while watching Warhol films and at the same time guide that awareness to a goal.

Not all of the structural films respond to the severe challenges of their form. Those instances of structural cinema in the filmgraphies of men who had worked successfully in other modes tend to use the frozen camera, loop printing, the flicker effect, and rephotography to open up new dimensions within the range of concerns that they pre-established in their earlier works.

Just why, at approximately the same time, Stan Brakhage, Gregory Markopoulos, Bruce Baillie, and Ken Jacobs began to extend their art in this direction is difficult to determine. Warhol’s sudden shock-blow to the aesthetics of the avant-garde film was a factor, just as it was to film-makers like Michael Snow, Paul Sharits, George Landow and Hollis Frampton whose work largely lies within the domain of the structural film.

Michael Snow, the dean of structural film-makers, utilizes the tension of the fixed frame and some of the flexibility of the fixed tripod in Wavelength. Actually it is a forward zoom for forty-five minutes, halting occasionally, and fixed during several different times so that day changes to night within the motion.

A persistent polarity shapes the film. Throughout there is an exploration of the room, a long studio, as a field of space, subject to the arbitrary events of the outside world so long as the zoom is recessive enough to see the windows and thereby the street. The room gradually closes up its space (during the day, at night, on different film stocks for color tone, with filters, and even occasionally in negative) as the zoom nears the back wall and the final image of a photograph upon it—a photograph of waves. This is the story of the diminishing area of pure potentiality. The insight that space, and cinema by implication, is potential is an axiom of the structural film.

In a note for the fourth International Experimental Film Competition where it won first prize, Snow described the film:

Wavelength was shot in one week Dec. ’66 preceded by a year of notes, thots, mutterings. It was edited and first print seen in May ’67. I wanted to make a summation of my nervous system, religious inklings, and aesthetic ideas. I was thinking of planning for a time monument in which the beauty and sadness of equivalence would be celebrated, thinking of trying to make a definitive statement of pure Film space and time, a balancing of “illusion” and “fact,” all about seeing. The space starts at the camera’s (spectator’s) eye, is in the air, then is on the screen, then is within the screen (the mind).

The film is a continuous zoom which takes 45 minutes to go from its widest field to its smallest and final field. It was shot with a fixed camera from one end of an 80 foot loft, shooting the other end, a row of windows and the street. This, the setting, and the action which takes place there are cosmically equivalent. The room (and the zoom) are interrupted by 4 human events including a death. The sound on these occasions is sync sound, music and speech, occurring simultaneously with an electronic sound, a sine wave, which goes from its lowest (50 cycles per second) note to its highest (12000 c.p.s.) in 40 minutes. It is a total glissando while the film is a crescendo and a dispersed spectrum which attempts to utilize the gifts of both prophecy and memory which only film and music have to offer.5

He simplified the essential ambiguity in the film by describing one of the events as a death. The order of the actions is progressive and interrelated: a woman supervises the moving in of a bookcase; later she returns with another woman; they listen to the radio (a few phrases from “Strawberry Fields,” pop culture’s version of ontological skepticism) without talking; so far we are early in the film, the action appears random; midway through, a man breaks glass (heard offscreen) to get in an unseen door and climb the stairs (so we hear); he enters the studio and collapses on the floor, but the lens has already crossed half the room, and he is only glimpsed; the image passes over him. Late in the film, a woman returns, goes to the telephone, which, being at the far wall, is in full view, and in a dramatic moment which brings the previous events of the film into a narrative nexus, calls a man, “Richard,” to tell him there is a dead body in the room. She insists that the man does not look drunk, but dead, and she says she will wait downstairs. She leaves.

Had the film ended at that point, the image of death would have satisfied all the potential energy and anticipation built up through the film. But Snow prefers a deeper vision. We see a visual echo, a ghost image in black-and-white superimposition of discontinuous flashes of the woman entering, turning toward the body, telephoning, and leaving. Then the zoom continues, as the sound grows shriller, into the final image of the static sea pinned to the wall, a cumulative metaphor for the whole experience of the dimensional illusion in open space.

The events of Wavelength occur first as discrete actions or irreducible performances. But the pivotal telephone call bridges the space between their self-enclosure and the narrative. Snow exposes his cinematic materials in Wavelength (even more so in his later film, whose title is the mark  ) as momentary states within the work. The splice marks, flares of light, filters, different film stocks, and the focal interests of the room (the yellow chair against the far wall especially) create a calculus of mental and physical states, as distinguished from human events, which are as much a part of the body of the film as the actions I have dwelt upon. Things happen in the room of Wavelength, and things happen to the film of the room. The convergence of the two kinds of happening and their subsequent metamorphosis create for the viewer a continually changing experience of cinematic illusion and anti-illusion.

) as momentary states within the work. The splice marks, flares of light, filters, different film stocks, and the focal interests of the room (the yellow chair against the far wall especially) create a calculus of mental and physical states, as distinguished from human events, which are as much a part of the body of the film as the actions I have dwelt upon. Things happen in the room of Wavelength, and things happen to the film of the room. The convergence of the two kinds of happening and their subsequent metamorphosis create for the viewer a continually changing experience of cinematic illusion and anti-illusion.

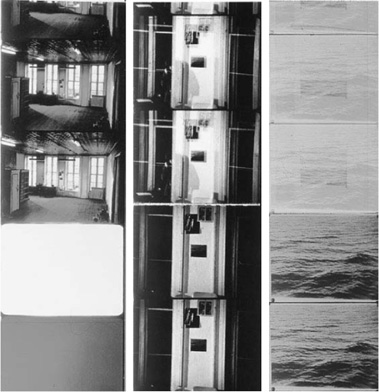

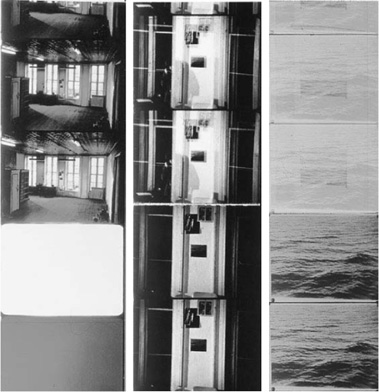

Three strips from Michael Snow’s Wavelength.

Annette Michelson finds this film a metaphor for consciousness itself. Her eloquent paraphrase reveals its relation to phenomenology:

We are proceeding from uncertainly to certainty, as our camera narrows its field, arousing and then resolving our tension of puzzlement as to its ultimate destination, describing in the splendid purity of its one, slow movement, the notion of the “horizon” characteristic of every subjective process and fundamental as a trait of intentionality. That steady movement forward, with its superimposition, its events passing into the field from behind the camera and back again beyond it, figures the view that “to every perception there always belongs a horizon of the past, as a potentially of recollections that can be awakened; and to every recollection there belongs as an horizon, the continuous intervening intentionality of possible recollections (to be actualized on my initiative, actively up to the actual Now of perception.” [Husserl, Cartesian Meditations] And as the camera continues to move steadily forward, building a tension that grows in direct ratio to the reduction of the field, we recognize, with some surprise, those horizons as defining the contours of narrative, of the narrative form animated by distended temporality, turning upon cognition towards revelation.6

The very unsteadiness of the forward movement and its perceptible tiny jolts forward confirm Michelson’s analysis. One of Snow’s most interesting tactics is the superimposition of the forthcoming, slightly forward position on the one we are looking at, giving us for the length of that superimposition a static image of the temporal process. Its most effective employment is at the very end of the film when, after a long-held wide shot, the photograph of the waves, surrounded by a border of the wall to which it is pinned, suddenly shares its screen space with a view within the photograph. We anticipate, and when the older layer dissolves we experience, the illusory depth of the receding line of sight extending over the static sea.

The structural film—and Wavelength may be the supreme achievement of the form—has the same relationship to the earlier forms of the avantgarde film that Symbolism had to its source, Romanticism. The rhetoric of inspiration has changed to the language of aesthetics; Promethean heroism collapses into a consciousness of the self in which its very representation becomes problematic; the quest for a redeemed innocence becomes a search for the purity of images and the trapping of time. All this is as true of structural cinema as it is of Symbolism.

For Snow, making a film is a matter of “stating the issues about film.” In an interview he said:

I thought that maybe the issues hadn’t really been stated clearly about film in the same sort of way—now this is presumptuous, but to say—in the way Cézanne, say, made a balance between the colored goo that he used, which is what you see if you look at it that way, and the forms that you see in illusionary space …. I was trying to do something very pure and about the kinds of realities involved.7

And in a letter following up the interview he added:

I mentioned Cézanne in a comment about the illusion/reality balance in art in painting. Tho many other painters have worked out their own beautiful solutions to this “problem,” I think his was the greatest and is relevant because his work is representational. The complicated involvement of his perception of exterior reality, his creation of a work which both represents and is something, thus his balance of mind and matter, his respect for a lot of levels are exemplary to me. My work is representational. It is not very Cezannesque tho. Wavelength and ↔ are much more Vermeer (I hope).8

Snow’s direct confrontation with aesthetic endurance was One Second in Montreal (1969), where more than thirty still photographs of snowcovered parks are held on the screen for very long periods. The shape of the film is a crescendo-diminuendo of duration—although the first shot is held very long, the second stays even longer, and so on into the middle of the film, after which the measures begin to shorten.

One Second in Montreal is one of several structural films that encroach upon the domain of the graphic cinema. It can be said that Wavelength bridges the distance between the subjective and the graphic poles by zooming the depth of the loft into the flatwork of the photograph. In One Second in Montreal Snow inverted the micro-rhythmic preoccupations of Kubelka and Breer by organizing his film around temporal differences that are barely perceptible because the attention of the viewer is permitted to wander and to change during the long holds.

In  (1969) and The Central Region (1971) the film-maker elaborated on the metaphor of the moving camera as an imitation of consciousness. The central fact of

(1969) and The Central Region (1971) the film-maker elaborated on the metaphor of the moving camera as an imitation of consciousness. The central fact of  is velocity. The camera perpetually moving, leftright, right-left, passes a number of “events” which becomes metaphors in the flesh for the back-and-forth inflection of the camera. Each activity is a rhythmic unit, self-enclosed, and joined to the subsequent activity only by the fact that they occur in the same space. They provide a living scale for the speeds of camera movement, and they provide solid forms in the field of energy that the panning makes out of space.

is velocity. The camera perpetually moving, leftright, right-left, passes a number of “events” which becomes metaphors in the flesh for the back-and-forth inflection of the camera. Each activity is a rhythmic unit, self-enclosed, and joined to the subsequent activity only by the fact that they occur in the same space. They provide a living scale for the speeds of camera movement, and they provide solid forms in the field of energy that the panning makes out of space.

The overt rhythm of  depends upon the speed at which the camera scans from side to side or up and down. Likewise, the overt drama of Wavelength derives from the closing-in of space, the action of the zoom lens. The specific content of both films is empty space or rooms. It is the nature and structure of the events within the rooms which differentiate the modes of the films.

depends upon the speed at which the camera scans from side to side or up and down. Likewise, the overt drama of Wavelength derives from the closing-in of space, the action of the zoom lens. The specific content of both films is empty space or rooms. It is the nature and structure of the events within the rooms which differentiate the modes of the films.

In the letter quoted earlier, Snow described  , which he was completing at the time:

, which he was completing at the time:

As a move from the implications of Wavelength  attempts to transcend through motion more than light. There will be less paradox and in a way less drama than in the other films. It is more “concrete” and more objective.

attempts to transcend through motion more than light. There will be less paradox and in a way less drama than in the other films. It is more “concrete” and more objective.  is sculptural. It is also a kind of demonstration or lesson in perception and in concepts of law and order and their transcendence. It is in/of/depicts a classroom. I think it will be seen to present a different, possibly new, spectator-image relationship. My films are (to me) attempts to suggest the mind to a certain state or certain states of consciousness. They are drug relatives in that respect.

is sculptural. It is also a kind of demonstration or lesson in perception and in concepts of law and order and their transcendence. It is in/of/depicts a classroom. I think it will be seen to present a different, possibly new, spectator-image relationship. My films are (to me) attempts to suggest the mind to a certain state or certain states of consciousness. They are drug relatives in that respect.  will be less comment and dream than the others. You aren’t within it, it isn’t within you, you’re beside it.

will be less comment and dream than the others. You aren’t within it, it isn’t within you, you’re beside it.  is sculptural because the depicted light is to be outside, around the solid (wall) which becomes transcended/spiritualized by motion-time whereas in Wavelength it is more transcended by light-time.9

is sculptural because the depicted light is to be outside, around the solid (wall) which becomes transcended/spiritualized by motion-time whereas in Wavelength it is more transcended by light-time.9

In the film the camera pans back and forth outside a schoolroom while a janitor crosses, sweeping, from right to left. The remainder of the film, which is fifty minutes long, takes place within that room. For the first thirty-five minutes the camera repeatedly sweeps past events or “operations,” to use the vocabulary of contemporary dance, usually separated from each other by passages of panning the empty room: a woman reads by the window, a class takes place in which the title symbol appears on the blackboard, a couple pass a ball, the janitor sweeps the floor, two men playfully fight, someone washes the window from outside, and a policeman looks in. The speed of the moving camera varies in relation to each event, sometimes to underline and sometimes to obscure the rhythm and axis of the activity; furthermore actors enter either by the door or suddenly appear and disappear through editing.

Midway through the film the event series ends. The camera accelerates, blurring the objects of the room, until the depth of space, which had been significantly asymmetrical—the camera being nearer one wall than the other—flattens into the two-dimensional. At the point of maximal speed the direction changes to the vertical and gradually slows to a stop. The film seems to have ended; the credits appear. Then the substance of the film is recapitulated in a coda.

The incessant panning of the camera creates an apparent time in conflict with the time of any given operation. In the film’s coda, which is a recapitulation of all the events out of their initial order and in multiple superimposition, the illusions of temporal integrity dissolve in an image of atemporal rhythmic counterpoint as all the directions and parts of the film appear simultaneously.

In the letter I have quoted, Snow wrote: “If Wavelength is metaphysics, Eye and Ear Control is philosophy and  will be physics.” Later he explained what he meant by these analogies. For him New York Eye and Ear Control analyzes modes of action, philosophy being a curriculum extending from ethics to logic, but excluding metaphysics (for Snow, the religious and perceptive dimension and the locus of paradoxes) which is the specific domain of Wavelength. Michelson’s brilliant analysis of the film does not account for its transcendental aura, which emerges, I believe, from the tension between the intentionality of the movement forward and the superhuman, invisible fixity of the tripod from which it pivots. That tension is in turn reflected and intensified by the corresponding opposition of the natural sounds to the electronic crescendo. And that tension climaxes in the final eerie plunge from the flat wall into the illusionary depth of the motionless seascape. Snow writes that he placed his camera and tripod on a pedestal to get a view of the street beyond the window, and he “discovered the high angle to have lyric God-like above-it-all quality.”

will be physics.” Later he explained what he meant by these analogies. For him New York Eye and Ear Control analyzes modes of action, philosophy being a curriculum extending from ethics to logic, but excluding metaphysics (for Snow, the religious and perceptive dimension and the locus of paradoxes) which is the specific domain of Wavelength. Michelson’s brilliant analysis of the film does not account for its transcendental aura, which emerges, I believe, from the tension between the intentionality of the movement forward and the superhuman, invisible fixity of the tripod from which it pivots. That tension is in turn reflected and intensified by the corresponding opposition of the natural sounds to the electronic crescendo. And that tension climaxes in the final eerie plunge from the flat wall into the illusionary depth of the motionless seascape. Snow writes that he placed his camera and tripod on a pedestal to get a view of the street beyond the window, and he “discovered the high angle to have lyric God-like above-it-all quality.”

The nearly mechanical scanning movement of  (he experimented with a machine that could swing the camera back and forth) takes a module of human perception and moves it in the direction of physical law, which denies to the human events it scans the internal cohesion of narrative, so that they in turn withhold from the camera the privilege of a fictive or transcendental perspective. Thus the film-maker compares the manifold to physics, or he can say, “You aren’t within it; it isn’t within you; you’re beside it.” Yet that does not exclude the possibility of an internal development within the film itself. In a text on The Central Region, he repeats and expounds his analogies:

(he experimented with a machine that could swing the camera back and forth) takes a module of human perception and moves it in the direction of physical law, which denies to the human events it scans the internal cohesion of narrative, so that they in turn withhold from the camera the privilege of a fictive or transcendental perspective. Thus the film-maker compares the manifold to physics, or he can say, “You aren’t within it; it isn’t within you; you’re beside it.” Yet that does not exclude the possibility of an internal development within the film itself. In a text on The Central Region, he repeats and expounds his analogies:

I’ve said before, and perhaps I can quote myself, “New York Eye and Ear Control is philosophy, Wavelength is metaphysics and  is physics.” By the last I mean the conversation of matter into energy. E=mc 2. La Région continues this but it becomes simultaneous micro and macro, cosmic-planetary as well as atomic. Totality is achieved in terms of cycles rather than action and reaction. It’s above that.10

is physics.” By the last I mean the conversation of matter into energy. E=mc 2. La Région continues this but it becomes simultaneous micro and macro, cosmic-planetary as well as atomic. Totality is achieved in terms of cycles rather than action and reaction. It’s above that.10

I take the analogy of “the conversation of mass into energy” to be a description of the climax of  when the acceleration of the camera allows for a transition from the horizontal to the vertical and ultimately for simultaneous spaces and events in the superimposed coda.

when the acceleration of the camera allows for a transition from the horizontal to the vertical and ultimately for simultaneous spaces and events in the superimposed coda.

The Central Region reconciles the structural metaphors of Wavelength and  . The central region of the title is a nearly barren plateau, void of people or any signs of their existence, and this region is also the sky above it, which the camera sweeps in 360-degree circles, explores in expanding or contracting spirals, and crosses in zig-zagging pans, focusing on the ground around its base in flowing close-ups and the distant horizon in zooming telephoto shots; but it is also the invisible spherical space which the camera, despite its ingenious equatorial mount which can mechanically perform more motions than the subtlest of film-makers holding his camera by hand, cannot see because it is itself. The whole visible scene, the hemisphere of the sky and the ground extending from the camera mount (whose shadow is visible) to the horizon, becomes the inner circumference of a sphere whose center is the other central region: the camera and the space of its “self.” Nothing the camera passes acknowledges its existence, however tangentially; yet the film as a whole metaphorically describes the Romantic estrangement from nature; all of its baroque motions vainly seek an image in the visible central region that will illuminate the invisible one.

. The central region of the title is a nearly barren plateau, void of people or any signs of their existence, and this region is also the sky above it, which the camera sweeps in 360-degree circles, explores in expanding or contracting spirals, and crosses in zig-zagging pans, focusing on the ground around its base in flowing close-ups and the distant horizon in zooming telephoto shots; but it is also the invisible spherical space which the camera, despite its ingenious equatorial mount which can mechanically perform more motions than the subtlest of film-makers holding his camera by hand, cannot see because it is itself. The whole visible scene, the hemisphere of the sky and the ground extending from the camera mount (whose shadow is visible) to the horizon, becomes the inner circumference of a sphere whose center is the other central region: the camera and the space of its “self.” Nothing the camera passes acknowledges its existence, however tangentially; yet the film as a whole metaphorically describes the Romantic estrangement from nature; all of its baroque motions vainly seek an image in the visible central region that will illuminate the invisible one.

Curiously, this very unique film recapitulates the quests of two very different film-makers, Stan Brakhage and Jordan Belson. In its imagery and in its dynamics, The Central Region looks back upon Anticipation of the Night, in which Brakhage’s shadow self becomes the shadow of the camera mount. His exploration there through the moving camera of the child’s awakening consciousness has its corollary in the opening spiral of Snow’s film, where the space which the viewer must study for the next three hours gradually discloses itself as the image feels its way from close, out-of-focus ground to horizon. Their imagery coincides in visions of “moonplay”; the camera movement in both films makes the moon dance in the night sky. Brakhage ends with a defeating dawn; Snow includes a beautiful aube in the middle of his film. In many ways it is the most spectacular of the sixteen different sections, which vary from about three minutes to a half hour in length and are clearly punctuated by a glowing yellow X against a black screen. In the dawn scene, the slowly seeping light very gradually clarifies the landscape and at the same time allows us to perceive the camera movements. Brakhage’s probing camera, unlike Snow’s, is completely humanized. Its irregularities of movement are indices of the fictional self behind it. In its disembodied perspective the motion of The Central Region recalls that of Samadhi or World.

The crucial issue that separates Snow’s disembodied viewpoint from Belson’s is, of course, illusionist. Snow always incorporated an apperceptive acknowledgment of the cinematic materials and circumstances in his film. In the article on The Central Region he wrote:

Most of my films accept the traditional theater situation. Audience here, screen there. It makes concentration and contemplation possible. We’re two sided and we fold.… The single rectangle can contain a lot. In Région the frame is very important as the image is continually flowing through it. The frame is eyelids. It can seem sad that in order to exist a form must have bounds, limits, set, and setting. The rectangle’s content can be precisely that. In La Région Centrale the frame emphasizes the cosmic continuity which is beautiful, but tragic: it just goes on without us.11

Belson’s art seduces us away from the immediacy of the materials—the rectangular screen, the tripod, the focusing lenses—into an illusionary participation, while Snow’s transcendentalism is always grounded in a dialogue between illusion and its unveiling.

The metaphysical culmination of Wavelength had been the moment of breaking through the photographic surface; the “physical” turning point of  was the conversion of space into sheer motion. A similar conversion occurs in the last section of The Central Region. The camera circles so quickly that the motion is no longer read as camera movement and the landscape itself seems to fly. As the speed accelerates, the earth it photographs forms a spinning ball until the last image of the film defines the central region as a planet in space, recalling the same metaphor for consciousness in most of Belson’s work.

was the conversion of space into sheer motion. A similar conversion occurs in the last section of The Central Region. The camera circles so quickly that the motion is no longer read as camera movement and the landscape itself seems to fly. As the speed accelerates, the earth it photographs forms a spinning ball until the last image of the film defines the central region as a planet in space, recalling the same metaphor for consciousness in most of Belson’s work.

Paul Sharits’s films are devoid of mystical or cosmological imagery, but they aspire to induce changes of consciousness in their viewers.12 Writing about his most successful flicker film, N:O:T:H:I:N:G (1968), he uses the language of Tibetan Buddhism:

The film will strip away anything (all present definitions of “something”) standing in the way of the film being its own reality, anything which would prevent the viewer from entering totally new levels of awareness. The theme of the work, if it can be called a theme, is to deal with the non-understandable, the impossible, in a tightly and precisely structured way. The film will not “mean” something—it will “mean,” in a very concrete way, nothing.

The film focuses and concentrates on two images and their highly linear but illogical and/or inverted development. The major image is that of a lightbulb which first retracts its light rays; upon retracting its light, the bulb becomes black and, impossibly, lights up the space around it. The bulb emits one burst of black light and begins melting; at the end of the film the bulb is a black puddle at the bottom of the screen. The other image (notice that the film is composed, on all levels, of dualities) is that of a chair, seen against a graph-like background, falling backwards onto the floor (actually, it falls against and affirms the edge of the picture frame); this image sequence occurs in the center, “thig le” section of N:O:T:H:I:N:G. The mass of the film is highly vibratory color-energy rhythms; the color development is partially based on the Tibetan Mandala of the Five Dhyani Buddhas which is used meditation to reach the highest level of inner consciousness—infinite, transcendental wisdom (symbolized by Vairocana being embraced by the Divine Mother of Infinite Blue Space). This formal-psychological composition moves progressively into more intense vibration (through the symbolic colors white, yellow, red and green) until the center of the mandala is reached (the center being the “thig le” or void point, containing all forms, both the beginning and end of consciousness). The second half of the film is, in a sense, the inverse of the first; that is, after one has passed through the center of the void, he may return to a normative state retaining the richness of the revelatory “thig le” experience. The virtual shapes I have been working with (created by rapid alternations and patterns of blank color frames) are quite relevant in this work as is indicated by this passage from the Svetasvatara Upanishad: “As you practice meditation, you may see in vision forms, resembling snow, crystal, smoke, fire, lightning, fireflies, the sun, the moon. These are signs that you are on your way to the revelation of Brahman.”

I am not at all interested in the mystical symbolism of Buddhism, only in its strong, intuitively developed imagistic power. In a sense, I am more interested in the mantra because unlike the mandala and yantra forms which are full of such symbols, the mantra is often nearly pure nonsense—yet it has intense potency psychologically, aesthetically and physiologically. The mantra used upon reaching the “thig le” of the Mandala of the Five Dhyani Buddhas is the simple “Om”—a steady vibrational hum. I’ve tried to compose the center of N:O:T:H:I:N:G, on one level, to visualize this auditory effect.13

Kubelka has posited Arnulf Rainer as the absolute pole of “strong articulations,” the split-second collision of opposites, black and white, silence and white sound. In The Flicker, Tony Conrad extended that technique to an area of meditative cinema by orchestrating smooth transitions between white dominance and black dominance and by keeping his piercing soundtrack at an even level. Lacking the internal modulation of Arnulf Rainer, The Flicker uses the aggressive speed of the flicker effect to suggest a revelatory stasis or very gradual change.

When Paul Sharits made the first color flickers—Ray Gun Virus (1966) and Piece Mandala/End War (1966)—he further softened the inherent strong articulations. Pure colors when rapidly flashed one after the other tend to blend, pale, and veer toward whiteness. By the time he made N:O:T:H:I:N:G he had learned how to control these apparent shifts and to group his color bursts into major and minor phrases with, say, a pale blue dominant at one time, a yellow dominant at another. From the very beginning the screen flashes clusters of color, while the sound suggests a telegraphic code, chattering teeth, or the plastic click of suddenly changing television channels.

In the middle of the chain of color changes he shows us an image interlude of a chair animated in positive and negative. It floats down the screen, away into nothing, or the near nothing of the mutually effacing colors. The interlude is marked by the sound of a telephone. From early on, the film is continually interrupted for short periods by the twodimensional image of a light bulb dripping its vital light fluid.

Sharits molds the viewer’s attention and punctuates it by incorporating into his seemingly circular flicker films (the mandala is his chosen shape) linear signs for determining how much of the film’s time has expired, how much is yet to come. The dripping bulb is one such clock; we anticipate that the film will end when it does. Ken Jacobs shows us the original Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son first so that we can gauge the development of his variations, only to trick us at the end, as Nelson does when he lies about the time of Bleu Shut. Sharits, however, seems to be interested in maintaining the purity of the relation between the duration of his films and the internal expectations and milestones they generate.

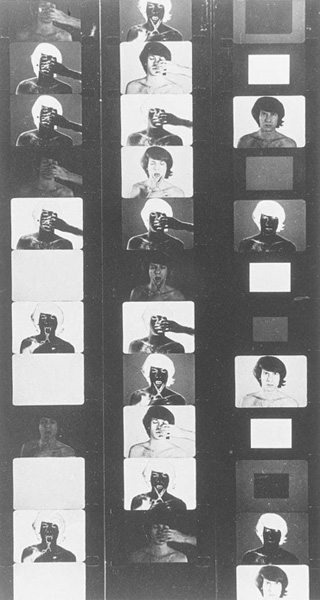

In T, O, U, C, H, I, N, G (1968) he spells the title out, letter by letter, beginning with the T and ending the film with the G. Here still images begin to assume equal weight with the color flicker. Single-frame shots of a shirtless young man flash in positive and negative, both color and black-and-white. In some of the shots he holds his tongue in a scissors as if about to cut it off; in others a woman’s fingernails are scratching his face. Two different stills of the scratching, in quick succession, test the spectator’s tendency to elide them into an illusion of movement. Mixed with these icons of violence are a photograph of an operation in color and a closeup of genitals in intercourse in black-and-white. All through the film the word “destroy” is repeated by a male voice in a loop. Eventually the ear refuses to register it, and it begins to sound like other words.

He makes similar use of the word “exochorion” in his subsequent film S:TREAM:S:S:ECTION:S:ECTION:S:S:ECTIONED (1970), this time spoken fugally with similar words by female voices. On the screen we see, for the first time in a Sharits film, a moving image—flowing water.

While the cycles of water current decrease three times in layers of superimposition from six to one, the number of vertical scratches on the film steadily increases in increments of three. The viewer clocks the film in relation to his expectation that when there is no more room for three additional scratches the film will end.

The multiple superimposition of water flowing in different directions initially presents a very flat image. But the subsequent scratches, which are deep, ripping through the color emulsion to the pure white of the film base and often ploughing up a visual residue of filmic matter at the edges, affirm a literal flatness which makes the water appear to occupy deep space by contrast.

The dilemma of Sharits’s art has turned on the failure of his imagery to sustain its authority in the very powerful matrix of the structures he provides. His search for metaphors and icons for the particular kind of cinematic experience that his films engender has not been as successful as his invention of markers to reflect the duration of his films. In N:O:T:H:I:N:G the off-balance, empty chair and the draining light bulb allude to the floating, almost intoxicating experience the seated viewer feels after extended concentration on flickering colors, pouring from the projector bulb. The metaphors of T, O, U, C, H, I, N, G totalize the suicidal and sexual inserts of Ray Gun Virus and Piece Mandala/End War and represent the viewing experience as erotic violence. Curiously in s:s:s:s:s:s he represents, unwittingly of course, the metaphor Kubelka is so fond of elaborating for the structure of Schwechater; in his lectures he always compares that film to the flowing of a stream. In Sharits’s film too, the complexly deflected water flows are like the illusory movement of cinema. However, these metaphors either lack the immediacy of the color flickers or the scratches around them, or they overpower their matrix, as in T, O, U, C, H, I, N, G, and instigate a psychological vector which the form cannot accommodate as satisfactorily as the trance film or the mythopoeic film.

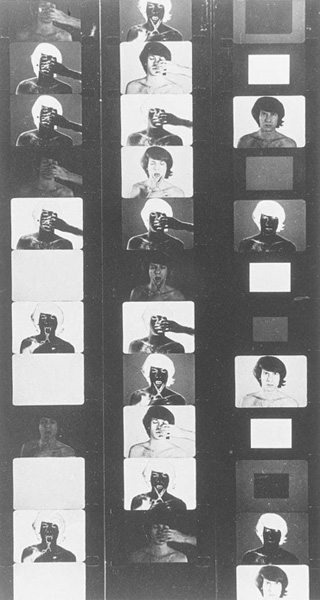

Flicker and sparagmos: Paul Sharits’s T, O, U, C, H, I, N, G.

It is precisely such a gift for finding the apperceptive trope that distinguishes George Landow’s films. His first film, Fleming Faloon (1963), is a precursor of the structural tendency. The technique of direct address is at the center of its construction. The film begins with two amateurs reciting “Around the world in eighty minutes”; then it contains jump-cuts of a TV newscaster and image upon image of a staring face, sometimes full screen, sometimes as the object of a dollying camera with the face superimposed upon itself. At other times the film splits into four images (unsplit 8mm photography in which two sets of two consecutive images appear in the 16mm frame). Televisions, mirrored televisions, and superimposed movies are interspersed.

In Film in which there appear sprocket holes, edge lettering, dirt particles, etc. (1966), he derived his image from a commercial test film, originally nothing more than a woman staring at the camera, in which a blink of her eye is the only motion, with a spectrum of colors beside her. Landow had the image reprinted so that the woman and the spectrum occupied only one half of the frame, the other half of which is made up of sprocket holes frilled with rapidly changing edge letters, while on the far right, half of the woman’s head appears again.

When the strip was to become Film in which, Landow instructed the laboratory not to clean the dirt from the film and to make a clean splice that would hide the repetitions. The resulting film, a found object extended to a simple structure, is the essence of minimal cinema. The woman’s face is static—perhaps a blink is glimpsed; the sprocket holes do not move but waver slightly as the system of edge lettering flashes around them. Deep into the film the dirt begins to form time patterns, and the film ends.

Bardo Follies (1966) refers in its title to the Tibetan Book of the Dead. The film begins with a loop-printed image of a water flotilla moving past a woman who waves to us at every turn of the loop. After about ten minutes (there is a shorter version too) the same loop appears doubled into a set of circles against the black screen. Then there are three circles for an instant. The film image in the circles begins to burn, creating a moldy, wavering, orange-dominated mass. Eventually the entire screen fills with one burning frame which disintegrates in slow motion in an extremely grainy soft focus. Another frame burns, and the whole screen throbs with melting celluloid. Probably this was created by several generations of photography off the screen—its effect is to make the screen itself seem to throb and smolder. The anticipatory tension of the banal loop is maintained throughout this section in which the film stock itself seems to die. After a long while it becomes a split screen of bubbles created when the projector lamp burns emulsion, with a different color on each side of the screen. Through changes of focus the bubbles lose shape and dissolve into one another. Finally, some forty minutes after the first loop, the screen goes white.

In The Film That Rises to the Surface of Clarified Butter (1968), Landow extends the structural principle of the loop into a cycle of visions. Here we see in black-and-white the head of a working animator; he draws a line, makes a body; then he animates a grotesque humanoid shape. In negative a woman points to the drawing and taps on it with a pencil. This sequence of shots—the back of the animator, the animation, the negative woman looking at it—occurs three times, but sometimes there is more negative material in one cycle than in another. Next we see the animator, this time from the front; he is creating a similar monster; he animates it. Again we see him from the front; again he animates it. Such is the action of the film. A wailing sound from Tibet accompanies the whole film. The title as well is Eastern: Landow read about “the film that rises to the surface of clarified butter” in the Upanishads.

The ontological distinction between graphic, two-dimensional modality (the monsters) and photographic naturalism (the animators, even the pen resting beside the monsters as they move in movie illusion), which is used as a metaphor for the relation of film itself (a two-dimensional field of illusion) to actuality, is a classic trope implicit since the beginning of animation and explicit countless times before Landow. Yet this is the first film constructed solely around this metaphor.

Landow’s structural films are all based on simple situations: the variations on announcing and looking (Fleming Faloon), the extrinsic visual interest in a film frame (Film in which there appear sprocket holes, edge lettering, dirt particles, etc.), a meditation on the pure light trapped in a ridiculous image (Bardo Follies), and the echo of an illusion (Film That Rises to the Surface of Clarified Butter). His remarkable faculty is as maker of images, for the simple found objects (Film in which and the beginning of Bardo Follies) he uses and the images he photographs are radical, superreal, and haunting.

Several film-makers extended their aspirations for an unmediated cinema which would directly reflect or induce states of mind and which first generated the structural film, into a participatory form which addressed itself to the decision-making and logical faculties of the viewer. George Landow and Hollis Frampton were the most significant film-makers to span the transition from structural to participatory modes.14 This shift marks an evolution within the structural film.

Institutional Quality (1969), Remedial Reading Comprehension (1971), and What’s Wrong with This Picture? (1972) constitute Landow’s contribution to this development. As in all his previous films the form of Institutional Quality is closed and more or less dominated by a single image. In this case it is a schoolmarm, administering to the viewer experiences reminiscent of childhood psychological perception tests and the television series Winky Dink and You, in which children were encouraged to draw upon a transparent sheet over the television screen, guided by an instructor on the air. Landow’s teacher instructs us, “There is a picture on your desk,” and we see a bourgeois living room whose only sign of motion is the banding fluctuation of its television screen. The instructions of the teacher remain accurately within the rhetoric of testing, but the montage of the film and the apperceptive condition of the viewer make these instructions ironic. After calling our attention to the picture of the living room, she says, “Do not look at the picture,” an order that the film spectator must blatantly ignore. At the end when she says “Now write your first name and your last name at the bottom of the picture,” the image flares to white before we see that the film-maker has written his name at the end of his picture: “By George Landow.”

When the voice instructs the viewer to put the number 3 over the object one would touch to turn on the television, a hand as big as the whole living room appears and pencils a three on the television screen, which destroys our illusion of scale and indicates the literal flatness of our own motion picture screen. Throughout the film the voice continues these instructions, and whenever the living room is visible, the hand obeys. There is no let-up in the voice, but more and more the image cuts away from the middle-class living room to pictures and questions about 8mm and 16mm films. The numbering of the objects in the room is reflected in the printed numbers over the picture of a projector indicating its operating parts. In a final didactic gesture, titled “A Re-Enactment” in letters printed over the image, an embarrassed and giggling woman demonstrates the threading procedure for loading an 8mm projector. “A Re-Enactment” is itself part of the television rhetoric used to describe the dramatization of the comparative testing of similar products within a commercial.

The fumbling and embarrassed performance of the demonstrator points up Landow’s growing concern with facsimiles and counterfeits. In the second part of What’s Wrong with This Picture? he remade an instructional film about civic ethics, with slight flaws. The shaky superimpositions and the quality of performance in the demonstration of equipment in Institutional Quality participate in this aesthetic of faulty facsimiles.

In Remedial Reading Comprehension he repeats and varies many of the tactics of the previous film, but this time he includes an actual found object along with his counterfeits. A speed-reading training film flashes short phrases from a sequential text. The whole of Remedial Reading Comprehension is a film of short phrases in an ambiguously didactic sequence. Dream inspiration and academic education are conflated in an opening that cuts from a sleeping woman to a classroom, expanding from a corner of the screen above her as if it were a “balloon” until it fills the screen, blotting her out. At the cry of “lights,” a faked commercial for rice appears, contrasting a grain of brown rice with one of converted rice.

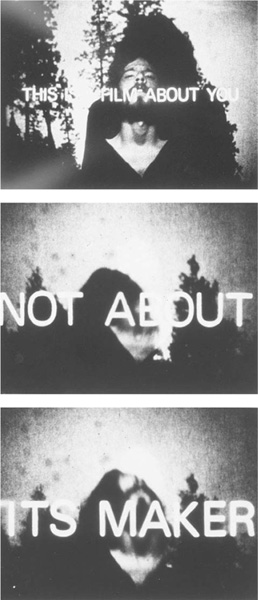

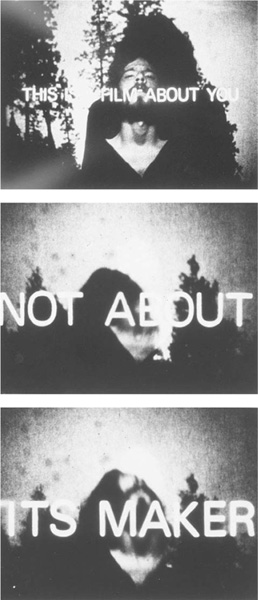

The act of reading is amplified by bracketing two images of the filmmaker running in flattened space created by rephotography off a screen; over his doubly superimposed picture appears the statement, “This Is A Film About You.” When the running image returns, the sentence concludes. “Not About Its Maker.”

Landow has referred to these films as an autobiography. It is an autobiography, or more exactly a bildungs-roman, devoid of psychology, moving in an elliptical leap from childhood and grammar school to college. Hollis Frampton too has used the participatory film for the indirect and serial “autobiography,” Hapax Legomema, a title derived from classical philology, referring to those words of which only one instance survives in the ancient texts.

Just before embarking on the serial film, Frampton completed his major work, Zorns Lemma (1970). This film is divided into three sections: an initial imageless reading of the Bay State Primer; a long series of silent shots, each one second long of photographed signs edited to form one complete Latin alphabet; and finally a single shot of two people walking across a snow-covered field away from the camera to the sound of a choral reading.

The first of several intellectual orders which Frampton provides as structural models within the film is, of course, the alphabet. The Bay State Primer announces, and the central forty minutes of this hour long film elaborates upon it. Within that section a second kind of ordering occurs; letters begin to drop out of the alphabet and their one-second pulse is replaced by an image without a sign. The first to go is X, replaced by a fire; a little later Z is replaced by waves breaking backwards. Once an image is replaced, it will always have the same substitution; in the slot of X the fire continues for a second each time, the sea rolls backwards at the end of each alphabet once the initial substitution occurs. On the other hand, the signs are different in every cycle.

The substitution process sets in action a guessing game and a timing device. Since the letters seem to disappear roughly in inverse proportion to their distribution as initial letters of words in English, the viewer can with occasional accuracy guess which letter will drop out next. He also suspects that when the alphabet has been completely replaced, the film or the section will end.

A second timing mechanism exists within the substitution images themselves, and it gains force as the alphabetic cycles come toward a conclusion. Some of the substitution images imply their own termination. The tying of shoes which replaces P, the washing of hands (G), the changing of a tire (T), and especially the filling of the frame with dried beans (N) add a time dimension essentially different from that of the waves, or a static tree (F), a red ibis flapping its wings (B), or cattails swaying in the wind (Y). The clocking mechanism of the finite acts is confirmed by their synchronous drive toward completion which becomes evident in the last minutes of the section.

In an elaborate set of notes on the film and its generating formulas, Frampton even describes its structure as autobiographical, the three parts corresponding to his Judeo-Christian upbringing, his development from being a poet to a film-maker while living in New York City, which is the background of the signs and replacements, and finally a prophecy of his move to the country. He lists the criteria for choosing the replacements as:

George Landow in Remedial Reading Comprehension: the text declares the participatory film’s paradoxical inversion of the trance film.

1. banality. Exceptions: S, C (animal images);

2. “sculptural” as distinct from “painterly” (as in word-images) work being done, i.e. illusion of space or substance consciously entered and dealt with, as against mimesis of such action. Exceptions D.K (cutting cookies, digging a hole);

3. Cinematic or para-cinematic reference, however oblique. To my mind any phenomena is para-cinematic if it shares one element with cinema, e.g. modularity with respect to space or time.

Consider also the problems of alternating scale, and maintaining the fourfold HOPI analysis: CONVERGENT VS. NON-CONVERGENT/RHYTHMIC VS. ARHYTHMIC.15

In the final section the visual pulse shifts to the aural level as six women recite the translation of Grosseteste’s “On Light, or the Ingression of Forms” in phrases one second apiece. His decision to allow one second to be the pulse of his film attempts to replace Kubelka’s reduction to the metric of the machinery (the single frame) with an arbitrary tempo. This is one of several totalizations and parodies of the quests of the graphic film in Zorns Lemma. The blank screen of the opening section had been one; secondly, by mixing flat collages with the actual street signs in the middle section, he compounded the paradoxes of reading and depth perception that the graphic film inherited from Léger, and which Landow explored in his participatory films.

In Zorns Lemma Frampton followed the tactics of his two elected literary masters, Jorge Luis Borges and Ezra Pound. From Borges he learned the art of labyrinthine construction and the dialectic of presenting and obliterating the self. Following Pound, Frampton has incorporated in the end of his film a crucial indirect allusion; it is to the paradox of Arnulf Rainer’s reduction. In Grosseteste’s essay, materiality is the final dissolution, or the point of weakest articulation, of pure light. But in the graphic cinema that vector is reversed. In the quest for sheer materiality—for an image that would be, and not simply represent —the artist seeks endless refinement of light itself. As the choral text moves from Neoplatonic source-light to the grosser impurities of objective reality, Frampton slowly opens the shutter, washing out his snowscape into the untinted whiteness of the screen.

Zorns Lemma takes its title from set theory, where it seems that “every partially ordered set contains a maximal fully ordered subset.” The units of one second each, the alphabets, and the replacement images are ordered sets within the film. Our perception of the film is a participation in the discovery of the ordering. Other Frampton films derive their titles from specialized disciplines—physics in the case of States (1967/1970), Max well’s Demon (1968), Surface Tension (1968), and Prince Rupert’s Drops (1969), and philology in Palindrome (1969)—and take their structural models from the academic disciplines.

A film such as Zorns Lemma must come about from an elaborate preconception of its form. That kind of preconception is radically different from the organicism of Markopoulos, Brakhage, Baillie, and indeed most of the film-makers treated in the early and middle chapters of this book. In the elaborate chain of cycles and epicycles which constitutes the history of the American avant-garde film, the Symbolist aesthetic which animated the films and theories of Maya Deren returns, with a radically different emphasis, in the structural cinema. Although dream and ritual had been the focus of her attention, she advocated a chastening of the moment of inspiration and a conquest of the unconscious, a process which she associated with Classicism. The film-makers who followed her pursued the metaphors of dream and ritual by which she had defined the avant-garde cinema, but they allowed a Romantic faith in the triumph of the imagination to determine their forms from within. From this aesthetic submission grew the trance and the mythopoeic film. When the structural cinema repudiated the credo that film aspires to the condition of dream or myth, it returned to the Symbolist aesthetic that Deren had defined, and in finding new metaphors for the cinematic experience with which to shape films, it reversed the earlier process so that a new imagery arose from the dictates of the form.

) as momentary states within the work. The splice marks, flares of light, filters, different film stocks, and the focal interests of the room (the yellow chair against the far wall especially) create a calculus of mental and physical states, as distinguished from human events, which are as much a part of the body of the film as the actions I have dwelt upon. Things happen in the room of Wavelength, and things happen to the film of the room. The convergence of the two kinds of happening and their subsequent metamorphosis create for the viewer a continually changing experience of cinematic illusion and anti-illusion.

) as momentary states within the work. The splice marks, flares of light, filters, different film stocks, and the focal interests of the room (the yellow chair against the far wall especially) create a calculus of mental and physical states, as distinguished from human events, which are as much a part of the body of the film as the actions I have dwelt upon. Things happen in the room of Wavelength, and things happen to the film of the room. The convergence of the two kinds of happening and their subsequent metamorphosis create for the viewer a continually changing experience of cinematic illusion and anti-illusion.