NOTHING LIKE THE peaks of excitement which had occurred in 1963 or 1968 was to be repeated in the subsequent decade. A great many of the most important films made during the period were the works of already established film-makers, although a few significant new names will be introduced in the pages that follow. In general it was a decade of new and different kinds of showcases for avant-garde films, and of the incorporation of film-makers and their films into the academic establishment. The previously undisputed pre-eminence of the American avant-garde was powerfully challenged by several flourishing movements in Europe, especially in Germany and England. Finally, the rudimentary development of an art of video drew some attention and excitement away from avant-garde filmmaking.

Within the internal history of cinematic forms constituted by the major new films three loosely related tendencies have dominated: (1) there has been a revitalization of the interest, both practically and theoretically, in the relationship between images and words. This is not merely a return to the issues of the 1950s which generated a widespread concern about the interpenetration of poetry and cinema. It is above all a dialectical development of the issues raised in the phase I have called “structural film.” (2) An elaborate autobiographical genre has emerged, often coinciding with the examination of the image/language relationship. In certain crucial cases language has been the means of redefining, within autobiographical films, the temporality of the film-making and film-viewing experiences. (3) The tendency toward a reduction and “purification” of the cinematic image continued and even grew stronger during the seventies.

Since historical change necessities a re-evaluation of origins, perhaps it would be useful to step back and re-examine a major avant-garde film of the twenties in the light of its repercussions in the seventies. Therefore, before analyzing the central films of the decade, I would like to consider some of the achievements of Marcel Duchamp’s Anémic Cinéma (1926).

For Duchamp the word “cinema” yields the anagram “anemic.” His film is both an “anemic” example of cinema (a work reduced almost to bloodlessness through the radical constriction of representational space) and perversely a demonstration of the “anemia” of all cinema. Eight disks of different graphic spirals alternate with eight on which elaborate puns have been printed spirally, so that each sentence begins at the perimeter and ends at the center of the revolving circle. The motion of the camera records their illusionary movement. Although there is no ontological difference between the image of a moving disk with concentric (and eccentric) circles and the image of a similar disk with letters rather than spiral lines, the automatic optical response of the viewer shifts at each change from spirals to words, and this is the main point of the film. The eye and the mind of the viewer perceive each geometric spiral as a whole; the circular movement imbues it with an illusion of depth, so that it seems either to protrude from the plane of the screen or to recede into it.

We respond to printed words quite differently. In order to read them, which entails the normal left to right scanning along a horizontal line, the eye tends to fix on a point and to allow the rotating words to pass by, left to right, into legibility. The optical illusion of depth generated by the graphic spirals corresponds to the “translation” of the letters into sound, words, and meaning in the act of reading. This correspondence is deliberately problematic. Both are interior reflexes to the optical stimuli of the film frames, but the route of their synthesis is particularly devious.

We must remember the status of the intertitle during the flourishing period of the silent cinema. It was a standard procedure to introduce each film episode with a title—almost a chapter heading—which would provide whatever information the director thought important in establishing the context, time, place, and emphasis of the scene to follow. The very rare efforts of such advanced directors as Lupu Pick, Kirsanoff, Murnau, and Vertov to eliminate intertitles merely testify to the fact that this dominant practice could become a conscious aesthetic problem. For Duchamp, as well as for his surrealist associate Robert Desnos (who collaborated with Man Ray on Étoile de Mer), the discontinuity between word and image in a silent film because the focus of an examination of the essence of cinema. The fusion of picture and text in Anémic Cinéma is elaborately ironic.

In order to understand that fusion we must pay close attention to the barely translatable puns.1 As they proceed one becomes aware of their strong sexual emphasis. The fifth and seventh are the most explicit: “Inceste ou passion de famille, à coups trop tirés” (Incest or family passion, with strokes too prolonged) and “Avez vous déjà mis la moëlle de l’épée dans le poële de l’aimée?” (Have you already put the marrow of the sword in the oven of the loved one?) The sexual allusions in these puns guide our reading of the others, both before and after, where allusions to defecation, breast-feeding, love bites, venereal disease, and orgasm occur.

Punning and internally rhyming language naturally refers to itself, closing off the world of the verbal disks into an autonomous entity. Two of the disks, the sixth and the ninth, thematically refer to their own linguistic gesture: “Esquivons les ecchymoses des esquimaux aux mots exquis” (Let us avoid the welts of esquimos with exquisite words). The mots exquis describe the very puns of the disks. The ecchymoses are inescapable once invoked by the puns; for a secondary (anemic) principle of association can inflect our perception of the graphic disks after reading the puns. Then the emerging and receding spirals come to look like the welts of the Eskimos’ love bites, or the intercourse of the sword in the oven, or the breast the infant sucks. The final, ninth, disk declares the position of the author: “L’aspirant habite javel et moi j’avais l’habite en spirale” (The aspirant lives on Javel and I had the spiral costume). This is one of several French sentences in the film that are contaminated by English idiom. Javel is not only a Parisian avenue but part of a vulgar expression for semen. The author (moi) is both differentiated from and identical to the erotic aspirant, for he has an “inspired” habit of language, but he also has his penis (labitte) in a spiral. This last possibility acknowledges that the sexualization of the graphic illusions is a complicated reflex in the mind of the viewer. By the demonstration of this film, then, cinema is anemic because of its erotic timidness and its endless but elusive chain of associations trapped between pictorial illusion and verbal allusion; while this particular film is anemic because of its self-imposed rejection of the space and time of human action, the conventional domain of filmic representation.

The intricacies and the paradoxes of the word and picture relationship that Duchamp embodied in Anémic Cinéma were dramatically reconsidered in several major films of the seventies.

George Landow’s debt to Duchamp extends at least as far back as his Film in which there appear sprocket holes, edge lettering, dirt particles, etc., a filmic variation of the Duchampian “ready-made” (the film-maker has spoken of it in these terms). Aside from titles, language did not enter Landow’s film-making until Institutional Quality. Since then there has been a progressive emphasis in his works on the independence of linguistic systems, which he underlined by puns, palindromes, and prayers within those films. By and large language has played a decisive role in the fundamental critique which all of his films of the seventies have marshalled: the examination of the status of filmic imagery.

The problematic of the “picture” elaborately structures New Improved Institutional Quality: In the Environment of Liquids and Nasals a Parasitic Vowel Sometimes Develops, about which the film-maker wrote:

A reworking of an earlier film, INSTITIUTIONAL QUALITY, in which the same test was given. In the earlier film the person taking the test was not seen, and the film viewer in effect became test taker. The newer version concerns itself with the effects of the test on the test taker. An attempt is made to escape from the oppressive environment of the test—a test containing meaningless, contradictory, and impossible-to-follow directions—by entering into the imagination. In this case it is specifically the imagination of the filmmaker, in which the test taker encounters images from previous Landow films: the blinking test pattern girl from FILM IN WHICH THERE APPEAR EDGE LETTERING, DIRT PARTICLES, SPOCKET HOLES, ETC., and the running alien from REMEDIAL READING COMPREHENSION (where the “alienated” filmmaker himself appeared). The test taker is “initiated” into this world by passing through a shoe (the shoe of “the woman who has dropped something”) which has lost its normal spatial proportions, just as taking the test has caused the test taker to lose his sense of proportion. As he moves through the images in the filmmaker’s mind, the test taker is in a trance like state, and is carried along by some unseen force. This is an allusion to the “trance film” and the “triumph of the imagination” described in P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film. At the end of the film the test taker is back at his desk, still following directions. His “escape” was only temporary, and thus not a true escape at all.2

The first film that the 1976 New Improved Institutional Quality looks back upon is, of course, the Institutional Quality of 1968. In repeating most of the soundtrack of the first film, Landow shifts the “person,” which had been a second-person address to the camera as viewer (with the insertion of the first-person hand as both the film-maker and the mediator of the viewer). Naturally the synecdoche of the hand leaves the respondent’s age, sex, and characteristics unspecified. The tone of the questions, and the way they are repeated, suggest that the test is for a group of schoolchildren. There is comic irony, therefore, in seeing a man with gray hair look into the camera, as if at a teacher, and grimace as he tries to follow directions, at the beginning of the later film.

His responses at first resemble the earlier film: a large hand with a pen writes a number on the image of the television. But a dissolve readjusts the scale: the actor is suddenly in the actual room of the “picture” and he repeats his task by putting a number on the actual television. From this point until almost the end of the film, the man moves within the world of the “picture,” numbering things, not their depictions, and, in general, looking quizzically back at the camera as he tries to take the figurative instructions literally.

In the first version, sitting on the television was a framed picture that was the object of an instruction. That it was a “picture” was all Landow showed; we could not make out the image within the frame. In the later film it is a color photograph of a woman, herself “framed” by a threedimensional pattern of color bands. The image is a “facsimile” with some displacement of the single image of Landow’s Film in which there appear sprocket holes, edge lettering, dirt particles, etc., where a woman in a found bit of commercial color test-pattern blinks repeatedly in a loop. The examinee dutifully numbers this photograph (or pseudo-still) from the film-maker’s earlier work.

The most striking sequence in New Improved Institutional Quality begins when the man tries to number the shoe of “the woman who dropped something.” As he crawls toward her foot, the scale shifts once more. He is suddenly crawling within an enormous replica of her shoe. It seems to be about twelve feet long and seven high. As he examines the shoe a telephone rings and the instructor says, “Answer the telephone, answer the telephone, put a number 4 on what you would touch.” This is the only correspondence between sound and instruction in the test; the telephone never enters the “picture.” As the examinee tries to respond, he floats off as if in a trance, past two images from Landow films. The woman of the photograph, her image filling the whole screen, has come alive and blinks at the camera, and another actor, running in place, wears the sign “This is a film about you,” which is a displaced facsimile from Remedial Reading Comprehension. He never reaches the telephone. The film ends with a shot of him at his desk as he was in the beginning.

The two facsimiles by which Landow chooses to represent his cinematic imagination are very interesting. In the case of the blinking woman, the image Landow used in Film in which was something he found, not something he made up or imagined. So here he re-imagines her twice. First, as a still photograph, a parody of a graduation portrait that might be found in the type of middle-class home represented in the “picture.” Second, the mechanical illusion of loop printing, her blink, becomes a physical attribute. The jogging figure too is no longer an image born of the film laboratory when words were superimposed over an already doubled image. Like an obsessed preacher, he carries his sign. Landow offers a paradox of subjectivity: the film-maker is most himself, truest to his style, either when he finds his shot, or when he is denying his centrality to his own film. For in re-imagining the sequence from Remedial Reading Comprehension he has chosen to objectify the most ambiguous moment in his works.

As in several other Landow films there is a linguistic reference in the full title, New Improved Institutional Quality: In the Environment of Liquids and Nasals a Parasitic Vowel Sometimes Develops. Landow has said that this subtitle, which he found in a book on language, struck him because of the ambiguities of the words “liquids,” “environment,” and “parasitic.” A perfect example of parasitic vowel formation is the pronunciation “filum” for “film.” According to the theme of the film, in certain environments the imagination temporarily manifests itself. It is parasitic to the extent that it cannot invent images out of nothing, but shifts scale, takes the figurative literally, alters materials, condenses and displaces elements from its past experience.

The two earlier “autobiographies” of artistic incarnation, Institutional Quality and Remedial Reading Comprehension, postulated the moment of becoming a film-maker as the moment of recognizing the ontological instability of filmic representation. The converse moment would occur when the film-maker considers his images as if they had a life of their own: their status would be “improved.” That is what momentarily happens in the version of 1976.

Landow emphasizes the temporary, and therefore illusionary, quality of the imaginative environment. In this respect, with characteristically ambiguous irony, he has some fun with the conclusion to the first edition of Visionary Film. The opposition of imagination and time is fundamental to Landow’s criticism of cinematic imagery.

The films of artistic incarnation are all investigations of repetition. In Institutional Quality the very repetition of threading and projecting the film appears at almost the last moment to confound the pseudo-decisions about how to start to make films. The point of origin in Remedial Reading Comprehension is itself repeated and varied: a dream, a class, a film, an advertisement, the reading of a text. It is re-medial, and involved with a new origin and a new artist, to undo the patterns of aberration already inscribed in dreams, schools, films, advertisements, tests, and texts. New Improved Institutional Quality locates the moment of imagination in the momentary illusion that images are “things you would touch.” This is not an eternal realm; and unlike some of his fellow avant-garde film-makers Landow does not seem to believe that the artist has a privileged relationship with God. The realm depicted here is parasitic, continually shifting and displacing images taken from all that has already been made, including art, even the art of the “same” film-maker.

For Landow the problematics of time in the context of filmic imagery are at odds with both the eschatology and the temporal/eternal distinction in his Christian films. Wide Angle Saxon (1976) provides the occasion for Landow to demonstrate, albeit ironically, his view of the status of cinematic imagery in a Christian vision that acknowledges a rational historical order, taking its meaning from the historical drama of Christ as the fulfillment of ancient prophecies and the definition of the future of time. The film obliquely describes the conversion of a television worker, Earl Greaves, who hears but rejects the proselytizing of a Messianic rock group in the course of his work only to be convinced by it, suddenly, while politely clapping for an avant-garde film that has bored him. Interspersed throughout this narrative are found (ready-made) mistakes of a news item about the Panama Canal, culminating in the superimposition of the palindrome “A Man, A Plan, A Canal: Panama!,” mental images apparently from the fictional Earl Greaves’s dreams, and comments about the process by which this and other Landow films were made. A final shot puts the authority of the whole film in question: a woman awakes with a gasp and exclaims, “Oh, it was only a dream.” (Landow considered making a series of films which would end with this line.)

Within the various episodes representing mental imagery, the Freudian principles of condensation and displacement are demonstrated. Landow incorporates free play between the linguistic and visual aspects of the film in this process. The palindromes and the repetitions of shots constitute an arbitrary, cyclic, and reversible order in contradistinction to which he posited the Christian revelation and the decisive moment of conversion. While the film mocks itself, its maker, and, in the hilarious preaching of a rock singer, its religious theme, it slyly invites the viewer to actualize the conversion attributed to its fictional protagonist. The Duchampian vertigo of word and image, he proposes, can only be surmounted by a more radical “imaginative” and “eternally present” leap into faith.

The boring avant-grade film which provides Earl Greaves with an opportunity to reflect on a biblical passage that sticks in his mind is incorporated, as a negative moment, within Wide Angle Saxon. Its title, “Regrettable Redding Condescension,” is a parody of Remedial Reading Comprehension, but the film itself explicitly parodies Hollis Frampton’s (nostalgia). The imaginary film-maker to whom Landow attributes the film-within-his film is Al Rutcurts, an anagram for “structural,” a term I have used in this book to describe an aspect which Landow’s work shares with several of his contemporaries, who, by the way, share his objections to generic association.3

Frampton’s (nostalgia) is another autobiography of artistic incarnation; it retraces the artist’s evolution from a still photographer to a filmmaker. The film uses a series of systematic displacements between language and image, between flatness and depth, between stillness and motion. The most striking of these displacements is linguistic, which very obviously undermines the indexical unity of picture and sound. Such a unity was manifested in Jerome Hill’s Film Portrait (1971), the first major work in this genre, every time he used the word “this.” (“It would be nice if this would happen again,” he tells us, and we take the “this” to refer unproblematically to what we see, say, the presentation of an award.) Frampton does not respect this form of unity. He shows us a still photograph and while we are looking at it, he tells us about the next one we will see. Yet he does so without letting us in on the displacement. The present tense and the demonstrative pronouns are deliberately deceptive. In this way the correspondence between picture and description is postponed until the viewer makes the adjustment, which can be after several of the stills have gone by. This simple technique effectively unpacks the temporal category of the present in the film; the words anticipate the pictures, the pictures recall the words, so that as we look at the film we are induced to perform simultaneous acts: to imagine a photograph which would correspond to the description (and thereby to repeat again and again the recognition of the limitations of the pictorial imagination), to remember the earlier description and appreciate the irony with which it describes what we are seeing, and finally to experience, in the present, the disjunctive synchronicity.

But that is not all. The photographs rest, one at a time, on a hotplate. After some minutes the shape of the electric coils begins to burn its way through. The new, pristine photograph comes on only after the previous one has been reduced to a crisp. The metaphor of the consumption of memory turns into an ironic joke. Yet at the same time, without any visible cause, the still image has turned into a moving (burning) one; each time the fire comes as if from within the still. In this transformation we repeatedly recognize our disorientation; for we are looking down upon the horizontal hotplate although our tendency is to interpret the internal orientation of the photographic image as a vertical camera setup. Finally, the patently flat space of the still’s surface, with its illusionary mapping of depth, turns into the shallow depth of the space between the hotplate and the camera, or at least the illusionary mapping of that depth on the flatness of the film screen.

The anticipatory descriptions leave one image unaccounted for: the first, of the darkroom itself; and one left to the imagination: the last, which is said to be so horrifying that it terminated the artist’s will to be a still photographer. The temptation is set for us to interpret the film’s time as circular. This temptation is even greater the first time one sees the film when the image of the darkroom has so faded in the memory that it is all the more susceptible to the paranoid rhetoric of the final description, which I will quote in full:

Since 1966 I have made a few photographs. This has been partly through design, and partly through laziness. I think I expose fewer than fifty negatives a year now. Of course I work more deliberately than I once did, and that counts for something. But I must confess that I have largely given up still photography.

So it is all the more surprising that I felt again, a few weeks ago, a vagrant urge that would have seemed familiar a few years ago: the urge to take my camera out of doors and make a photograph. It was a quite simple, obtrusive need. So I obeyed it.

I wandered around for hours, unsatisfied, and finally turned towards home in the afternoon. Half a block from my front door, the receding perspective of an alley caught my eye … a dark tunnel with the cross-street beyond brightly lit. As I focussed and composed the image, a truck turned into the alley. The driver stopped it, got out, and walked away. He left his cab door open.

My composition was spoiled, but I felt a perverse impulse to make the exposure anyway. I did so, and then went home to develop my single negative.

When I came to print the negative, an odd thing struck my eye. Something, standing in the cross-street and invisible to me, was reflected in a factory window, and then reflected once more in the rear-view mirror attached to the truck door. It was only a tiny detail.

Since then I have enlarged this small section of my negative enormously. The grain of the film all but obliterates the features of the image. It is obscure; by any possible reckoning, it is hopelessly ambiguous.

Nevertheless, what I believe I see recorded, in that speck of film, fills me with such fear, such utter dread and loathing, that I think I shall never dare to make another photograph again.

Here it is!

Look at it!

Do you see what I see?4

If the film describes a circle, then the horror is the terror of solipsism, of finding only the metonymies of one’s origins in the accidents of exterior vision. This may only be a deliberate attempt to make us consider the seductions of the myth of cyclical time, and again be confounded. There is still another obscure option. The one thing one does see after the question, “Do you see what I see?” is the film-maker’s monogram, the HF with which he signs his film. Yet this holds even less satisfaction than the circular form. The simple, unbearably ironic answer to the final question must be: “No. I do not see what you see.” The narrator is no longer listening, of course. But that seems to be much of the point—the fruitlessness of the entire subjectivist quest, so complexly articulated by Brakhage, of establishing a correspondence, or even a calculus of the limits of a correspondence, between the film-maker’s vision and his films. Frampton is having his cake and eating it too; but that indeed may be his definition of all autobiographical madness. The very wantonness of the pronoun “I” does not escape him. In “A Pentagram for Conjuring the Narrative,” he wrote:

“I” is the English familiar name by which an unspeakably intricate network of colloidal circuits—or, as some reason, the garrulous temporary inhabitant of the nexus—addresses itself; occasionally, etiquette permitting, it even calls itself that in public. How it came to be there (together with some odd bits of phantasmal rubbish) is a subject for virtually endless speculation: it is certainly alone; and in time it convinces itself, somewhat reluctantly, that it is waiting to die.5

In the film, Michael Snow reads the text Frampton wrote. The language of the various descriptions freely mixes a great number of deliberately veiled personal references to events unrelated to images on the screen, often of an erotic nature, with parodies of several kinds of art-historical discourse. There is a hilarious Panofskian interpretation of the religious iconography of two toilets. The formalistic language associated with the followers of Clement Greenberg is finely misappropriated for a foundobject image of a forlorn planter among his flooded grapefruits. Vasarian biography, technical shoptalk, and art gossip have their chances as well. We are left, especially after the quasi-apocalyptic tone of the final text, with a thorough suspicion of the relationship of word to image, which corresponds apparently for Frampton with the moment of his incarnation as a film-maker.

The second description (and the third photograph) of (nostalgia) reflects the autobiographical paradox. The text promises a self-portrait of the artist at twenty-three years old and exults in the complete physical renewal of his cells since that time. There is considerable humor in hearing Snow delight in not being Frampton, or Frampton in not being himself, depending upon where one locates the narrative voice. If we believe this witty text there is hardly anything which connects either Snow or Frampton with the picture of the young man of a dozen years earlier.

In Landow’s parody we see red paint poured over a hot plate as part of Rutcurts’ “artistic” gesture of covering things arbitrarily with this color. When the paint begins to bubble we hear the voice of Michael Snow asking, “Do you see what I see?” Yet in the context of Wide Angle Saxon conviction through imagery is as superficial as Rutcurts’s condescending art. There is, however, a technical, theological meaning to the word condescension: it is the act of God the Father manifesting himself among men as the Son. It is to this alternative sense that Greaves attends in the film.

(nostalgia) is the first of seven parts in Frampton’s serial film Hapax Legomena (1971–1972). The title, a term from classical philology, refers to those words whose sense is ambiguous because they only occur once in surviving texts; their meaning can only be determined from context. Frampton has described the entire enterprise as a stereoscopic “superimposition of a personal myth of the history of one’s art upon a factual account of one’s own persona.” The seven parts are not equally explicit about the artist’s history, but they do each isolate a fundamental aspect of the ontology of cinema. Just as (nostalgia) concerns the limits of photography and its illusions, Poetic Justice, the most Duchampian of the series, brings to the fore the concept of the film-script. The film must be read. On the screen remains a table with a small cactus and a cup of coffee to either side of a stack of papers. On the top paper we read sequentially the descriptions of two hundred and forty different shots, organized in four tableaux. At the end Frampton signs the work with an homage to Duchamp’s “sculpture” of 1944, “Pocket Chess with Rubber Glove,” by leaving a rubber glove on top of the now blank papers. Within the context of the film the glove not only represents the absence of the authorial hand; it suggests, as well, a gynecological instrument.

Between the blank page and the absent hand Frampton proposes a language, laden with indexical shifters (I, you, this), which illustrates the fragility (or anemia) of the cinematic experience. The hypnogogic phase of his verbal film alludes to the art of Brakhage. In an interview with Simon Field, Frampton acknowledged his debt to Brakhage but made the following distinction in their attitudes toward vision:

Suppose I just propose a model that could include both of us, rather than one or the other of us, and suggest that Stan has been concentrating for a long time on a different segment of the seeing or perceiving process than I have been concentrating on. There’s no question at all in my mind about the debt that I personally owe to Brakhage’s work.…But I remember very, very clearly having in my still photographs felt that I was being forced into film …And one of the deciding things was a suspicion that there were, after all, some films that Stan Brakhage had not made.…Well, there was nevertheless something, not that he avoided, but that had not at that time centered his own preoccupations, and that still had to do with seeing certainly … you know, that is the core doctrine, seeing with the eye is still the centre of the whole thing. OK. But there is also seeing that is done very far back in the centres of the brain. There other seeing gets done, like those blind people who can touch things and tell you what color they are, and so forth. We’re talking about a sense that’s not a sense at all but a cluster of senses.… Well, what Brakhage did distinctly suggest, and I think not only to me, was that seeing as a kind of total psycho-chemical, or psycho-physical phenomenon, was a continent, and not just a pipe that things ran in through.6

Poetic Justice represents an extreme limit of “seeing that gets done very far back in the brain.” It is also the farthest Frampton’s cinema has moved from the aesthetic of Brakhage. In what had been publicly exhibited of Frampton’s immense work-in-progress Clouds of Magellan—a composite film which he once estimated would run for twenty-four hours—the filmmaker seems to have been attempting to grapple with the stylistic and thematic priority of Brakhage’s art.

Frampton succeeded Brakhage, however, as the principal voice of American avant-grade film theory. In his crucial essay, “A Pentagram for Conjuring the Narrative,” he attempted a definition of the fundamental characteristics of cinema. It is worth nothing that he introduced his own theoretical pronouncement with a reflection on the title of Marcel Duchamp’s final work, Étant Donnés: I La chute d’eau, 2 Le gaz d‘éclairage (1946–66).

Marcel Duchamp is speaking: “Given: 1. the waterfall; 2. the illuminating gas.” (Who listens and understands?)

A waterfall is not a “thing,” nor is a flame of burning gas. Both are, rather, stable patterns of energy determining the boundaries of a characteristic sensible “shape” in space and time. The waterfall is present to consciousness only so long as water flows through it, and the flame, only so long as the gas continues to burn.

You and I are semistable patterns of energy, maintaining in the very teeth of entropy a characteristic shape in space and time.

What are the irreducible axioms of that part of thought we call the art of film?

In other words, what stable patterns of energy limit the “shapes” generated, in space and in time, by all the celluloid that has ever cascaded through the projector’s gate? Rigor demands that we admit only characteristics that are “totally redundant,” that are to be found in “all” films.

Two such inevitable conditions of film art come immediately to mind. The first is the visible limit of the projected image itself—the frame—which has taken on, through the accumulation of illusions that have transpired within its rectangular boundary, the force of a metaphor for consciousness itself. The frame, dimensionless as a figure in Euclid’s “Elements,” partitions what is present to contemplation from what is absolutely elsewhere.

The second inevitable condition of film art is the plausibility of the photographic illusion. I do not refer to what is called “representation,” since the photographic record proves to be, on examination, an extreme abstraction from its pretext, arbitrarily mapping values from a long sensory spectrum on a nominal surface. I mean simply that the mind, by a kind of automatic reflex, invariably triangulates a precise “distance” between the image it sees projected and a “norm” held in the imagination. (This process depends from an ontogenetic assumption peculiar to photographic images, namely that every photograph implies a “real” concrete phenomenon (and “vice versa!”); since it is instantaneous and effortless, it must be “learned.”)

Recently, in conversation, Stan Brakhage (putting on, if you insist, the mask of an “advocatus diaboli”) proposed for film a third axiom, or inevitable condition: narrative.7

Hapax Legomena is a demonstration of these principles. The status of the photograph and the status of narrative are “issues” in the first two films of the series. The seventh or final segment, Special Effects, simply shows the filmic frame, depicted by a broken white line around a black rectangular void. Frampton filmed this static graphic design with a hand-held telephoto lens from a distance so that the nervous jittering of his body, as a ground or base for the camera, would be recorded simultaneously with the universal outline of the frame.

One might further note that the last segment he filmed for Hapax Legomena, even though it is sixth in the order of screening, was originally to have the Duchampian title Given:.… before he settled on Remote Control. This part and Travelling Matte are complementary meditations on the relationship of video to film: one from the point of view of a static observer, reconstructing the narrative of television shows through singleframe montage; the other stressing the moving body of the artist as he makes one long continuous take in which he masks the image with his hand.

The most comprehensive, and the most impressive, of the serial films of the seventies was Michael Snow’s Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen (1974), a 285-minute-long “encyclopaedia” of sound and image interaction, with numerous debts to the work of Duchamp. Passages of pure color alternation punctuate the twenty-four loosely interwoven episodes (Frampton was also fond of multiples of twenty-four; he called it cinema’s “magic number”) which are followed by an erratum and an addendum. The episodes are so varied in their different approaches to the possibilities of sound and picture fusion that the film challenges both description and analysis. Its maze-like system of internal cross-references and its disguised allusions to the contents and forms of Snow’s earlier films would require considerably more space just to be noted comprehensively than a survey chapter can allot.

Whereas the three earlier long films upon which Snow’s eminence as a film-maker rests—Wavelength, and La Région Centrale—propose modes of camera movement as models of cognition, Rameau’s Nephew … lacks a single defining gesture of the camera; it explores the whole human body as a field of epistemological inquiry. Speaking, focusing, singing, urinating, laughing, reading, whistling, flatulating, eating, hand tapping, and fornicating are chief among the types of bodily activity and noise heard and discussed in the film. The actual sounds are often rendered in a deliberately unnaturalistic manner through a series of self-conscious acts of recording and editing: proximity to the microphone, modulation during a take, superimposition of sounds, and substitution in editing. This rendering of sonic perspective, which is analogous to the camera movements of the earlier films, retards the immediate assimilation of the sounds as language or as natural background; thus the range of difficulty of recognition from raw noise to articulate speech (and music) enters as a thematic element in the film. The whole rambling film seems organized around a dizzying nexus of polarities which include picture/sound, script/performance, direction/acting, writing/speaking, and above all word/thing. The film opens with an image of the film-maker whistling into a microphone and ends with a brief shot of a snowdrift, so that the work is bracketed by a rebus for Mike … Snow. The elaborately twisting movement across episodes, inspired in part by Diderot’s eccentric dialogical novel, passes freely from one aspect of human sound-making to another, with the speech organs at one pole and written words at the other.

Early on, Snow has someone read a text on the power of language to shape our concept of reality; this he filmed on color videotape. The reader re-divides the letters of the text so that the new phonic combinations are barely intelligible (emphasizing the fragility of the written alphabet). Furthermore the electronic color pattern of the videotape erratically responds to the pitch or stress of his alexical words. Even the titles of the film provide the occasion for grotesquely enlarging the already immense cast by the insertion of a long series of anagrams for Michael Snow: Wilma Schoen, Naomi S. Welch, El Masochism, Noel W. I. Chasm, Lemon Coca Wish, Male Cow Shin, Nice Slow Ham, Malice Shown, etc., etc. He even invents a purely cinematic palindrome near the middle of the film by having a group of actors read the words of their script backward (e.g. “?Nushiv fuh trawf uth sith si”), and then, after showing the episode as it was shot, he prints it in reverse so that their conversation about flatuence approaches the threshold of conprehensibility. The example I quoted becomes a crude joke on Brakhage: “Is this the fart of vision?”

The epistemological dimensions of the film become more thematically explicit at its conclusion. A long episode in a hotel involves numerous allusions to the film we are watching (“This film looks like [pause] it was hewn with an axe.” “How can you say that [pause] if you’re in it?”) and its modes of construction (after musical notes are synchronized with a moving mouth someone observes, “I didn’t know you spoke trumpet”). The cliché “seeing is believing” generates a long series of variations beginning with “hearing is deceiving.” The inquiry into the conditions of empirical certainty, which this casual conversation initiates, climaxes in a hilarious debate about the reality of a table, a parody of Plato’s theory of forms in the Republic. After one character angrily demolishes it with an axe to prove his point, its purely verbal existence is momentarily asserted.

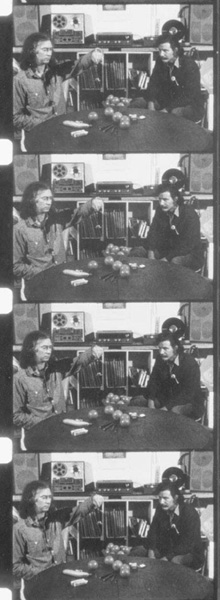

Michael Snow (left) in his Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen.

“Maybe it’s a multiplication table.” “If it is a vegetable we can prove that ‘eating is believing’ which is what I believe.” Then Snow brilliantly manifests the table again in superimposition, so that, even though we can “see” it, it cannot support the cups and saucers the actors try to place on it. Here the very insufficiency of film, as a representational system, to prove anything about the nature of representation, becomes the object of a demonstration. The debate shifts from metaphysical certainty to eroticism with equally comic and paradoxical dramatizations of the gulf between cinema and experience. In the final scene, before the addendum, Snow underlines the discrepancies between names and things which he had been enumerating in his film. Sitting at a table, he shows us three objects. For a pair of finger cymbals he makes the sound which can be written either “cymbal” or “symbol.” Holding up an orange, he says “orange”; then, finally, presenting a banana, he says “yellow.” This short episode intends to catch the viewer off guard and it illustrates his dependence on a simplified concept of language in which there is an adequation of things and names. Snow saves one interpretive ambiguity, worthy of Duchamp’s heritage, for the addendum, which is a dedication to Dennis Young who first suggested to the film-maker that he read Diderot as source-material for a new film. Elevator doors open and the dedicatee sticks out his tongue. An exhibition of the organ of speech or a message to the viewer? Both, of course. The presentation of the source of articulation coincides with a fully articulated gesture.

Within Rameau’s Nephew …, Michael Snow is a name, a configuration of letters, a rebus, an offscreen (directing) voice, and an image or visible body. Language, in the wide sense projected by the film, is the matrix of forces requiring us to see the signs as substitutions for things before the mystery of what a thing is can even become an issue. This stress on the prestructuring of language, on its priority to perception, accounts for the cinematic style of the film. It is particularly interesting that Snow, in forgoing his accustomed strategy of making the camera the center of cognition, and by coolly observing the body as the locus of information (even for himself, for there is no transcendental perspective reserved for the film-maker here), created a form which allows language to control an and organize his film: for long stretches the montage responds to shifts of syllable, word, phrase, sentence, or speaker. The underlying authority posited by the film resides neither in the filmic syntax nor in the body as the object of observation, but in the ambivalent interpretive contract between the two. Music represents the upper limit of this contract, the obscene gesture (sticking out the tongue, for instance) the lower; between them mediates the self-referentiality of speech, as in the riddles Snow repeats through his actors: “Why is black music so popular?” “Because you can’t see white music on the page”; or “Why does a hummingbird hum?” “Because it doesn’t know the words.”

The choreographer, Yvonne Rainer, began her film-making by exploring the parameters of narrative language in her three long films, Lives of Performers (1972), Film about a Woman Who … (1974), and Kristina Talking Pictures (1976). She has described the first of them in the following note:

Lives of Performers, the 16mm film I directed in the Spring of 1972 (Cinematographer—Babette Mangolte), unfolds in roughly fourteen episodes, each having a different cinematic approach toward integrating real and fictional aspects of my roles of director and choreographer and the performers’ real and fictional roles during the making of previous work and the film itself. The first section (and a later one) is edited footage of an actual rehearsal of Walk, She Said for a live performance (Performance at the Whitney Museum). The second shows photographs of Grand Union Dreams while the voice-over narration describes the content of the photos and the changing intimacies of these same performers—fictional in this instance. In other sections the narrative zigzags along as the performers talk and move about in a barren studio setting containing a couch and several chairs. A simultaneous voice-over commentary by the performers themselves—sometimes read, sometimes improvised from the scenario—alternating with inter-titles, constantly interprets the enigmatic sequences of unheard (seen) discussion and implied emotional complexities. The narration is further complicated by the fact that part of it was recorded during an actual performance, so that the laughter of the then-present audience is heard at various times. Valda Setterfield performs a solo dance at one point (which I had originally choreographed for Grand Union Dreams). It is not very well appreciated by Fernando Torm, her (presumed) lover. (“He has seen it a hundred times.”)

The film ends with a “real performance,” a series of imitations of stills from G. W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box or Lulu. The other performers are John Erdman, Shirley Soffer, Epp Kotkas, James Barth, Sarah Soffer, and myself as director.9

In the extraordinary series of dance concerts Rainer created and performed throughout the 1960s she often incorporated narrative texts, allusions to famous films, and even film clips. Her cinematic style originates with a network of gestures locating herself in intersecting traditions of cinema, fiction, and performance. In her first two films the fluid, sinuous and utterly distinctive camerawork of Babette Mangolte, who shot much of Rameau’s Nephew …, heightens the severe withdrawal from the conventions of fictional representation in the visual dimensions of her work. In Film about a Woman Who … the optical reconstruction of a psychological scenario is accompanied by a dispassionately delivered commentary in several voices which portrays the histories, memories, thoughts, and fears of the utterly unrealistic characters we see on the screen. The paradigmatic tension of text and image is visualized when Rainer’s face appears with paragraphs of printed prose stuck on her cheeks and forehead. Variations on this gesture occur in the form of silent title cards and superimposed subtitles throughout the film.

Brakhage was responding to Frampton’s Zorns Lemma when he made The Riddle of Lumen (1972), but he could equally have addressed his note on the film to the recent work of Landow or Snow. He wrote:

The classical riddle was meant to be heard, of course, its answers are contained within its questions; and on the smallest piece of itself this possibility depends upon SOUND —“utterly,” like they say …the pun its pivot. Therefore, THE RIDDLE Of LUMEN depends upon qualities of LIGHT. All films do, of course. But with THE RIDDLE OF LUMEN, “the hero” of the film is light/itself. It is a film I’d long wanted to make—inspired by the sense, and specific formal possibilities, of the classical Eng. lang. riddle … only one appropriate to film, and thus, as distinct from language as I could make it.10

The Riddle of Lumen presents an evenly paced sequence of images, which seem to follow an elusive logic. As in Zorns Lemma the viewer is called upon to recognize or invent a principle of association linking each shot with its predecessor. However, here the connection is nonverbal. A similarity, or an antithesis, of color, shape, saturation, movement, composition, or depth links one shot to another. A telling negative moment occurs in the film when we see a child studying a didactic reader in which simply represented objects are coupled with their monosyllabic names in alphabetical order.

Brakhage released more than fifty films in the seventies. Although the anxieties about the natural world which had generated so many of his early masterpieces seem to have diminished in the later films, the horrors of solipsism continue to plague him. In fact, several quasi-documentary films from this period—eyes (1970), Deus ex (1971), more problematically The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes (1971), and The Governor (1977)—constitute attempts to ground his perception in a firmly established exterior reality (the police, a hospital, a morgue, the official life of a politician) as a brake to his excessive and frightening tendency to interiorize all that he sees. However, they are far less significant than his prolonged autobiographical enterprise “The Book of the Film” or his tourde-force The Text of Light (1974).

For years he had been haunted by an empty boast made during his adolescence that he could shoot a feature film in a wastepaper basket. He finally satisfied himself by making The Text of Light in (through) a large crystal ashtray. This magnificent film—a slow montage of iridescent splays of light and shifting landscapes of sheer color, which acknowledges debts to Turner and American Romantic landscape painters as well as to James Davis, the pioneer film-maker of light projections—is the culmination of Brakhage’s exploration of anamorphosis. The Text of Light never explicitly presents the ashtray as an object; it is instead an extension of the lens, and a considerable amount of the film’s power derives from the recognition that it is a film created within the optics of the lens itself and its crystal extension. In blanking out the spatial configurations of the natural world, which he does more dramatically in this film than in any earlier work, Brakhage projects, in response, an optical nature that is fully his own.

Scenes from Under Childhood (1967–1970), a four-part film, is itself the first chapter of a projected giant work, “The Book of the Film.” Another chapter in three parts, The Weir-Falcon Saga, has also been completed. When Brakhage calls this work “an autobiography in the Proustian sense,” he means that the film makes no claims to represent the facts of his life; instead it reproduces the structures of his experience as he remembers them. The distinction Brakhage makes is between classical autobiography and the autobiographical novel. A more useful distinction can be drawn within the strict autobiographical tradition: Augustine in his Confessions presents himself as a typical man, in all else but the very fact that he writes. Rousseau, in his Confessions, portrays the extraordinary individual, an absolutely unique case. Brakhage has operated in both autobiographical modes. Scenes from Under Childhood and The Weir-Falcon Saga participate in the Augustinian manner. Their “fictional” principle is that the film-maker allows his observation of the events of his children’s lives to stand for his own life. But insofar as this substitution is overtly declared as such, and the distance between the film-maker and the children is inscribed in the structure of the films, the fiction dissolves. In its place there emerges the suggestion that the activities of children can reveal a universal model for psycho-history. Brakhage’s Rousseauistic confession, Sincerity (reel one) describes the events leading from his own childhood to the making of his first film.

The opening section of Scenes describes two contradictory movements: on the one hand we witness the emergence of consciousness from a red “pre-natal” field. Images of the child gradually come into focus; perspectives eventually stabilize into the synthetic unity of objects. Much of the film is a prolonged and wonderfully precise dramatization of the origins of sense certainty, something that Jerome Hill rapidly described in a recollection of his bedside clock but did not illustrate in Film Portrait. On the other hand, the forward movement of the film can be understood as the quest of memory: out of the red haze of the autobiographer’s closed eyes, memories come to the fore and slip away. The entire section, then, describes the difficult attempt to establish a cinematic transcription of memory.

In Scenes, and even more explicitly in Sincerity, Brakhage uses the photograph album as the external scaffolding of memory. In one way the film represents the impossible effort of the autobiographer to evoke memories from the photographs he finds in the snapshot albums of his and his wife’s childhood. The simultaneity of these several lines of development (the birth of consciousness, the will to remember, the reading of the album) determines the film’s skepticism. For Brakhage any genealogy of the mind must be a fiction; the autobiographer interprets the sequence of his coming to remember as the sequence of his life; and even that ordering needs the support of a conventional model, the snapshot album.

For the most part, the second section of the film explores the nature of play and imitation among the Brakhage children and introduces an analysis of their affections. An opening montage of rhythmic physical games, such as swinging and whirling, is soon superseded by a cluster of shots of the different children, at widely different ages, crying. Throughout this part the montage is exceptionally fluid, with the superimposition of phosphene imagery reinforcing the elisions. These impart to the thematic components (games, toys, imitation, emotions, and the parents’ sexuality) a sense of interlocking association. He cuts in an image from the photograph album only once here: the image of a boy, perhaps Brakhage himself, on a bicycle appears over the children riding their various vehicles. Perhaps more significantly there is a shot of Jane looking through the album itself in a context that suggests that even her nostalgic attraction to these past images constitutes a form-of, or an outgrowth of, play.

In the broad movement of the section there is a shift from physicalrhythmic games (the swing) to the use of vehicles and ultimately to mimetic toys. A transition that links images of a primal scene of the parents’ intercourse to the toys occurs when shots of the mother’s nude body and of the father urinating precede the image of an unclothed doll. Dollhouse play follows, and even the dressing of one doll in a wedding gown.

However, the crucial moment in the analysis of mimesis takes place earlier in the section. Brakhage establishes a metaphor for cinema, its framing process and illusory depth and movement, by superimposing very quickly several shots of a large window, filmed at varying distances. The frame rapidly contracts and expands, recedes and emerges, as the short views of the same “thing” are manipulated. This self-conscious figure of a film within the film is immediately followed by a clip from a televised Shirley Temple movie. The antithesis of the myth of happy childhood and the cinematic analysis of children could not be more bluntly articulated. Brakhage also shows us the enthralled and nervous expressions of his children as they watch the movie on the TV screen. He wants to underline the way in which mimetic representations of childhood help to form the children’s affective patterns and inculcate the mythology of childhood in them. The closing of this mimetic circuit is an important moment in Scenes, and reflects its circularity, which is indeed the basic circularity of serious autobiographical enterprises.

Many of Brakhage’s earlier films, and especially Dog Star Man, were eschatologically structured, moving from a pristine moment of origin to a totalizing end. All of his autobiographical works deny this eschatology, and, as I shall try to show, the theory of metaphor that attends it. In his autobiographical reflections, there can be no true beginning, no immanent structure, no totalizing end. As an autobiographer, he discovers that even his memory has been influenced by the scrapbook his mother structured, his emotional patterns trained by movies that pass on absurd myths of childhood.

In the fourth and final section of the film, this repetitive, circular genealogy of the psyche is re-articulated from a different perspective. Brakhage may be taking the liberty Gertrude Stein, one of his central sources, took when she wrote The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and Everybody’s Autobiography: for this part is centered on Jane. As she cries, apparently in prolonged grief, photographs of her mother and of herself as a child appear. These in turn are superimposed over her daughters. For the first time in the film a continuity is suggested in which the children repeat the patterns which they learned from their parents, while the parents can see their own patterns only as reflected in the children. Early in the film a cheerful snapshot of two children, presumably Jane and her brother, is superimposed over a fight among her children. Much later in the film her eldest daughter is isolated in tears, corresponding to the opening grief of the mother.

Near the end of the film we can catch the reflection of Brakhage filming the eyes of Jane and the children, his “eye” being the mechanical view-finder with its three lens sights. After this, he makes a disturbing appearance. Obviously in a foul humor he growls, “I’m hungry” (the phrase is easily read from his lips) and angrily shakes his finger at the camera. At the end of a sequence in which adolescent boys fly a remote-control model airplane, one of the boys twice describes the arc of the plane’s flight with a graceful arm and wrist gesture. Brakhage’s finger and the boy’s arm rhyme at the point in the film (the end) where Brakhage’s aggression is associated with a montage of youthful sports events. These events, intercut with a photograph of some institution, possibly a high school, represent a stage at which gesture and play become social aggregates.

The Animals of Eden and After (1970) portrays the process of convalescence as a normalization or accommodation to socially dictated patterns of perception and thought. According to the implicit scheme of the three films of The Weir-Falcon Saga, fever and illness so jar the perceptual patterns that a re-experiencing and a re-mythologizing of the world have to occur. The first part of the film is a metonymic series of shots of Brakhage’s home, interior and exterior, apparently from the point of view of the child. The surrounding landscape during different seasons, details of furniture, hearth-fire, children playing, and above all the numerous animals of the ménage (goats, birds, dogs, an ass) appear in a montage of wanton lushness. The motive for joining one shot to another is primarily optical as in The Riddle of Lumen, not conceptual; something in the texture, color, saturation, or rhythm of one shot calls for a complement in the next. Among the most characteristic images of this first part is one of the mother sunbathing, with a child at one side and a goat at the other. For Brakhage this metonymic sensual vision represents Edenic consciousness. He recognizes it not as an aboriginal state but as a moment situated between the fevered aberrations of intense illness and the conceptual and socially determined vision of the fully “recovered” child.

The turning point of the film follows the birth of a goat. Brakhage cuts from the color image of the animal’s labor to a black and white image of a crying baby. The shift in film stocks emphasizes the decisiveness of this moment. In the narrative of the film, this is the point at which the child, witnessing the birth of the animal, imagines his own birth. Since animals are so born, he must once have been. The actual birth is of course not within his conscious memory. Thus metaphor enters the scheme. It is an act of interpretation which brings the self of the observer into a regulatory relationship with what he sees. Metaphor is an act of identification, yet the act is predicated upon the difference of the elements which are to be equated. Every metaphor postulates a coherence where it first recognizes a disparity.

The child in Brakhage’s film takes the newborn goat as a type for his own invisible past; through metaphor he enters into the first and simplest autobiographical reflection; for it is with the introduction of this metaphoric montage that a linear operation of time enters the film. His recovery begins. He can play outside. There we see him recapitulating the primitive history of the species. He points his toy rifle at the dog, miming the primeval hunter. Mime itself is a further aspect of metaphor. At the moment when the child realizes he is like the goat, he realizes he is not precisely the same. Through metaphor he invents himself as human and reduces goats, dogs, etc. to the role of “animals.” Then they can be hunted, domesticated, even bottle-fed with a metaphoric rubber nipple.

The subsequent development of the film traces the amplifications of metaphor through play. With the initial recognition of the difference between animals and men comes a large increase in human power and authority, culminating in the eating of the animals who were bred and raised for that purpose. At the same time the animals are seen to have something that is lacking in man. To recover this loss the human resorts to sympathetic magic. We now see the child wearing various halloween masks and aping animal gestures. Shortly afterwards the canary we saw before in close-up, reappears, now clearly imprisoned in a cage. Two different metaphoric developments of the bird follow. First, continuing the postulate of the film-maker that the games of children recapitulate the origins of human religion, the canary is followed by the image of the child wearing a dimestore “Indian” headdress, which reminds us that these feathered chapelets gave their wearers the attributes of birds. Another sequence intercuts the caged bird with the crying child. Here is an elaboration of the initial man/animal comparison. The trapped bird now stands for the feelings of the weeping child. Metaphor comes to be the exterior representation of an invisible interiority. (In the portrait of his daughter Crystal in 15 Song Traits Brakhage earlier explored the cliché of representing a child’s sadness by a caged bird.)

The curtain of a stage and the edge of an American flag appear in the penultimate montage. The very fragmentation, the effectiveness of synecdoche at this point, is a formal demonstration of the triumph of conceptual montage. The curtain alludes to the prehistorical transition from sympathetic magic to religious, ritual theatre. The flag is the incarnation of the inflated symbol. Since the landscapes of the film represent the immediate environs of the Brakhage house in all the seasons, the vision of home is determined by the horizon. The idea of a nation is a succession of horizons, which can only be symbolically or metaphorically represented. The flag is the nation, visually. It is the largest and the most powerful of the film’s metaphorical movements away from the immediate and the optical.

All three films in The Weir-Falcon Saga end with a shot of the moon. In The Animals of Eden and After, that shot is immediately preceded by a shot of a Christmas-like decoration, a gilded tinsel in the shape of a fivepointed star. Here the difference between the popularized and secularized vestige of a religious ornament and a visible heavenly body (of which the ornament is an abstracted, formalized representation) is cumulatively illustrated. Not only is the difference perceptual; it is also historical, for the ornament not only represents a star, but also Christmas and the more ancient fertility festivals of which it is a survival.

Brakhage’s point is that we are always surrounded by a world of metaphors, overlaid like a palimpsest, conventionalized traces of once powerful perceptions, which induce us to see the world as reflections of ourselves. The child of his film, and the film-maker himself, for whom the son stands as an autobiographical metaphor, were born into and are part of such a world of symbolical meanings. His illness created a temporary disengagement from this world of symbolical meanings. His readjustment to the normal world takes the form of a myth of creation (The Machine of Eden,[1970]) followed by a myth of evolution. The key word in the title of the last film was “After.” Eden comes into existence only after it disappears. Any version of innocence is a negative metaphor, something unlike the present.

If The Animals of Eden and After explores the fact of cinematic succession as a model for autobiography, Sincerity (reel one) (1973) treats the autobiographical moment in terms of the encounter of camera and object. Just as the aftering of frames and shots is an a priori condition of all films, the stare of the camera at something is not the only, but certainly the overwhelmingly dominant, way of producing images on those frames. The theme of Sincerity (reel one) is Brakhage’s incarnation as an artist. Here he quests impossibly to represent the moment he became a film-maker. The time-span runs from his birth to the making of his first film, Interim.

The grandmother’s eyes and the mother’s face are the first images in Sincerity. The entire film might be seen as an elaboration on that moment, as if all that occurs, between the opening encounter of the camera with an old photograph and the final scene of the mature Brakhage staring into the camera, takes place during the moment of the film-maker’s meditation on the static image of his mother.

The photograph album is central to Sincerity. The film’s opening shots follow a pattern. The camera shifts from the young Brakhage in the pictures to some detail, for example, a trellis, part of a roof, in the background. Then in color, and with a moving camera, the film-maker seeks out that site today. The autobiographical dilemma of this film is the failure of a site to recover the plenitude of past experience. This is why so much of the film is a study of the campus of Dartmouth College, where he went for a semester before he quit while “faking” a nervous breakdown. Quitting college coincided with the decision to make films.

Isolated images which had been used metaphorically earlier in the film, such as some broken glass or a distorted reflecting surface, are encountered in the college episode as metonymic details of the environment. This strategy diffuses the earlier metaphors and puts into question the temporal organization of the whole film. However, the crucial metaphoric substitution is of a different order in this film from the comparable moment in The Animals of Eden and After. Brakhage is filming the view from the window of a college room when the scene cuts to himself in an expressionistic avant-garde film of the 1950s. He throws a cup of water against the wall of his room and, in frustration, moves to the window. This sequence is matched with the position of the window in the color sequence of the college. Here the implication is that the emotional tone which he cannot recover at present-day Dartmouth is preserved in the “fictional” film in which he acted soon after leaving the college.

After this turn, the film shifts to the site of his own first film, Interim. Fortunately for Sincerity, Stan Phillips, Brakhage’s cameraman for that initial venture, would take shots of the crew with the bits of film left near the ends of the reels. The young Brakhage seems to have deplored this playfulness; for he appears ordering the cameraman to stop. In any case, one has, for the moment of making Interim, what was lacking in the other moments of the autobiography, a filmic record. At least apparently so.

It is remarkable that none of the crew, nor the actors when they are not performing, can stand the gaze of the camera. They clown, grimace, turn away, blush, or order the shot stopped. The entire film, Sincerity, is directed toward this scene of recovered representation, which itself turns out to be camera shy.

Among the production clips from Interim is a long shot of the protagonist’s eyes. Brakhage quickly intercuts that youthful stare with his own eyes. The alternating montage creates an impossible mutual stare over more than twenty years. Of course, the displacement is not only temporal. Any encounter represented by the intercutting of two sets of eyes or two faces in cinema is mediated by the unseen presence of the camera. In this case, the actor looked into a camera in 1953 and Brakhage looked into one sometime in the 1970s. The alternating montage fictionally erased the presence of the camera and aligned the eyes. This substitution of another image for the presence of the camera is as important in defining the cinematic limitation of autobiography as is the more dramatic and obvious trope of the stare across time. For the one demarcation here of the present is the presence of the camera, but that present is always a past, or an absent, moment at the time of editing. The alternations of montage are tropes to recover the presence of the moment of filming. Again the encounter of self with self as dramatized in Sincerity becomes a study of the artificial temporality of all cinema. The moment of artistic incarnation is represented not as a moment within the film, but in a recognition of the status of cinema as demonstrated by the form of the film.

Stan Brakhage’s Sincerity (reel one). Two sequential images: Brakhage from Larry Jordan’s 1956 psychodrama, The One Romantic Venture of Edward (black and white), fused to a view of the Dartmouth campus from a window (color).

James Broughton’s Testament (1974) is the purest and to my mind the most powerful of the film autobiographies of the seventies. In style and in technique it is quite eclectic; its most moving sequence comes right out of Hill’s Film Portrait, a sequence of photographs in reverse chronological order. Yet an extreme and profound transformation of the strategies of autobiography is the result of Broughton’s art.

The opening trope brings together an allusion to Maya Deren (the reversed sea from At Land), who was one of the major inspirations of Broughton’s early cinema, and a recollection of “the aging balletomane” (the rocking chair), the icon of retrospective fancy in Broughton’s Four in the Afternoon. In this shot, the film-maker himself sits in a rocking chair on a beach. His rocking movement indicates a sympathetic union with the sea he contemplates. This image, with its several variations, including one using reverse photography (where Broughton walks backward out of the backward-rolling waves to reoccupy the empty chair), presents the constitutive moment of the film: everything occurs as if recalled from this extended rhythmic figure. The empty chair is one of the strong substitutions for the moment of death in Testament. When the film-maker comes back into it, he acknowledges the ad hoc cinematic illusion of autobiographical continuity. This metaphorical use of reverse motion also occured in Film Portrait. Broughton’s choice of imagery, his superb timing, and the quality of the verbal text which accompanies the images raise this figure to a power unanticipated by the self-irony of Hill’s film.

The other intimation of death, juxtaposed in the editing with the sequence of the empty chair, is the montage of photographs to which I referred. There are several interludes of still photographs, showing Broughton’s parents, his collaborators on the sets of his various films, and his home life. The most dramatic, however, occurs at the end of a processional march, in which the poet, in an elaborate feathered costume, is carried on a litter through the streets of Modesto, California, his birthplace, on a day when he was publicly honored by the town’s library. Parading with him, under the banner “In memory of James Broughton,” are many of his students costumed as totemic animals. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this procession is the inclusion of the faces of the puzzled and amused bystanders. Where Hill told of his family, “These people to whom I belonged, did not belong to me,” Broughton vividly demonstrates the isolation and the strangeness of his poetic vocation in this marvelous parade. The procession brings him to a graveyard. A shot of his fascinating, wrinkled face dissolves into the sequence of photographs in anti-chronological order. As the images rush toward infancy one sees the unmasking of the mature features as a movement towards an essence. It is as if after the earliest picture we should expect some image of primal nonexistence. Instead the montage cuts powerfully from the baby’s face to a still image of the aged poet under a weblike veil, which emphasizes both the lines of his face and the birdlike nature of his costume. In his text for the presentation of the Twelfth Independent Film Award, Ken Kelman described Testament as “a ritual mask with sardonic bite which opens to giddy depths and lets out the roar of good old animal spirits.”11 The whole processional sequence is the giddiest of those depths and one of the sublime moments of the cinema of the seventies.

The text of the film is an anthology of passages from A Long Undressing, Broughton’s collected poems, carefully excerpted and intoned as if they constituted a single autobiographical poem. Early in the film when a voice (presumably that of one of the townspeople watching the procession which is seen much later) asks, “Who is James Broughton?”, the citation is in fact from the poem “I Am a Medium,” the autobiographical forward to the collection:

I am a third generation Californian …

My grandfathers were bankers, and so was my father.

But my mother wanted me to become a surgeon.

However, one night when I was 3 years old

I was awakened by a glittering stranger

who told me I was a poet and always would be

and never to fear being alone or being laughed at.

That was my first meeting with my angel

who is the most interesting poet I have ever met.

The indifference to being alone or being laughed at is illustrated by the outrageous procession through Modesto, later in the film. But the moment of poetic incarnation is illustrated at this point by the dance of a nearly naked youth, in silver body-paint, with a long goatlike phallus, which he rubs against an immense egg, representing the poet. A motherly figure hovers over it too. Even Christ makes a brief appearance, to bless it.

The issue of artistic incarnation is fundamentally different in Testament from the variations we have observed in other film-makers. There is no question of psychological development, dramatic reorientation, or the patterning of aberrant responses. The story that Broughton tells us is of a calling, pure and simple. Perhaps not so simple. For it is a fusion of erotic and religious origins. The mythic representation of the angel poet, as well as of the Great Mother and Christ in this Orphic trinity, looks forward to another scene of incarnation, as a film-maker per se, a little later in the film. But before we can come to that point, a more detailed look at the modes of representation throughout the film must be taken.

Broughton represents his filmable life in terms of his actual films. Starting with a parody of the compositions and foreshortenings of Mother’s Day, with his son, Orion, standing in for the young poet, the sequence proceeds through a re-montage of The Adventures of Jimmy in which Broughton played the main role, Loony Tom, The Golden Positions, Nuptiae, This Is It and The Bed. Autobiography becomes, then, for Broughton, a particular (linear) mode of interpreting his works, both cinematic and verbal.

Into this matrix of poetic origins, as an interlude in the parody of Mother’s Day, Broughton inserts the fictitious projection, by the boy for himself, of The Follies of Dr. Magic. He introduces the film by saying, “To amuse myself I made my first movie,” and concludes bitterly, “I thought it showed great promise. Unfortunately no one else thought so.” The context might seduce us into assuming that the two sentences refer to The Follies of Dr. Magic, itself a parody of very early fantasy films, as Pathé or even Méliès made them. The title is an allusion to Gance’s early anamorphic film, The Folly of Dr. Tube, which is conventionally chronicled as the first avant-garde film. The statement, “To amuse myself I made my first movie,” however, might refer to either The Potted Psalm, which Broughton made with Sidney Peterson, or Mother’s Day, his first solo film. The latter reference is more likely, although the mention of negative critical reception is applicable to both. (Here the film-maker is taking some license; for all of his early films were well received, but only within the vary narrow circle of people who knew and cared about advanced cinema.)

It would seem that Broughton is not very interested in isolating the moment or the process of artistic incarnation, but in defining the way it sustains itself. The long hiatus in his film-making, from The Pleasure Garden to The Bed, 1953–1968, does not become an issue in this cinematic autobiography. The poems of those fifteen years represent the continuity that is dominant here. In fact, “I Asked The Sea,” the opening poem of Tidings (1964), provides the text for the opening and closing of the film:

I asked the Sea how deep things are.

O, said She, that depends upon

how far you want to go.

Well, I have a sea in me, said I, do you have a me in you?

As he rocks sympathetically by the shore Broughton is able to ventriloquize the ocean. But their “dialogue” gently touches upon the disharmony between the mortal self and the endlessly repeating sea. The initial appearance of the empty chair suggests that indeed the “me” of the film has entered the sea forever. But after the autobiographer returns, backwards, to his seat, the sea in the final passage wants to open up the theme of death:

Let’s talk of my dead,

the Sea said.

Let’s not, said I

I’m dry on my dune …

Then, said the Sea,

When I wash up the dead

will you wade in?

I’ll swim, I said.

Broughton rocking by the sea recalls a commonplace in American poetry initiated by Walt Whitman’s great poems of poetic incarnation: “A Word out of the Sea” (first titled “A Child’s Reminiscence” and from which the image of the ocean as “Out of the rocked cradle” comes), and “As I ebbed with an ebb of the ocean of life.” The Pacific is gentler to Broughton than the Atlantic was to the suffering Whitman in delivering the same deadly message. “I’ll swim” is a heroic taunt at the limitation of this metaphoric ocean, and it touches us precisely because it evokes the temporal advantage of the sea over the swimmer.

Song of the Godbody (1977) is another instance of Broughton’s homage to Walt Whitman. As the poet chants seventy-six verses of a paratactic poem celebrating the body, the camera lovingly explores his body in detail. In the course of its movement the camera startlingly encounters semen on the flesh. In almost every line the poem articulates an “I” and a “You”; these two verbal “persons” acknowledge the subject/object relationship of the visible body to the camera, as the voice calls to and interiorizes the intense gaze of the cameraman.