The need for change is something on which Cuban citizens, dissidents, exiles and even the government agree. However, whatever form Cuban society takes in the future, the Millennium Goals (which have already been met in Cuba) should be protected as one of the greatest treasures of this nation.

—Fernando Ravsberg, BBC, Havana, April 4, 2013[1]

The insightful BBC correspondent in Cuba is right. Cuba’s protection of many of the Millennium Goals (education, health care, the role of women, access to food, and protection of culture among others) is exceptionally good. During Fidel Castro’s many years as president, these social human rights developed faster than in any developing nation. (This can be seen in data for a variety of aspects of health and education, points that are developed later). But Fidel has now left the political scene, and his brother is in charge of an economy that is still extremely inefficient and where many of the reforms introduced have resulted in significant inequality for those unable to adapt to the rigors and fast pace of change in the new Cuba. One of the key questions to be asked in any analysis of contemporary Cuba is therefore whether the scope of the changes in the social fabric is sufficient to maintain the revolutionary process itself. This section seeks to provide a variety of elements to assist in that investigation.

The starting point for this section is our finding that there have been remarkable changes in Cuba since Raúl Castro assumed the presidency—many of which would have been inconceivable just a few years ago. In the first edition of A Contemporary Cuba Reader, we examined the significant evolution during the early years of the “Special Period”—especially in the early years after the implosion of the Soviet Union—and the enormous impact of these reforms on the society. We concluded that Cuba had changed more in those first four years of the Special Period than it had in the previous quarter of a century.

The impact of many of those reforms diminished as the Special Period continued through the late 1990s and into the first decade of the new millennium as the economy gradually improved. Self-employment decreased noticeably as many Cubans returned to work in state-controlled industries (in particular, the increasingly important tourist sector). Yet largely as a result of the new government policies, social differences increased, in part because the social (and racial) polarization continued to increase with an ever-wider gap in incomes. At the same time, the government continued to demand greater efficiency from those employed in state-run industries, even when the salaries were barely able to keep pace with the cost of living—and often they did not. It was clear that a fresh approach was needed since the blend of outdated socialist measures (in particular, massive subsidies to unproductive industries) and an incipient private sector (both being often connected with ties of petty corruption) badly needed to be overhauled. The impact of this complex, disturbing situation on social institutions and personal relationships was clearly becoming both untenable and embarrassing—and the government of Raúl Castro therefore embarked on a series of far-reaching measures designed to provide equality of opportunities to Cubans—without ensuring basic equality. Analyzing those dramatic changes in Cuban society, this section provides a set of totally new chapters and insights into some of the principal societal changes and challenges that have resulted.

Raúl Castro has certainly introduced a fresh approach. Gone are the earlier massive public demonstrations in favor of the “Cuban Five,” the sweeping condemnations of U.S. policy, and frequent use of state-controlled media to emphasize government campaigns. Instead, a low-key business-like approach has been steadily implemented. The same emphasis on efficiency and saving, with demands for harder work from state employees, and at the same time the same appeal for popular support for the Revolution are still found. But the basic strategy has changed dramatically, as have the fundamental policies in many other areas, as this book attests.

In many ways, the social changes that have resulted in Cuba since Raúl Castro assumed the presidency have significantly reduced the unique aspects of the revolutionary approach to social development. Efficiency, massive layoffs of workers, and a decrease in subsidies for many former unproductive factories are now the new order of the day, and, as Raúl Castro often says, this is a process “without haste, but without pause.” Some of the most notable programs remain with generous subsidies, and Cuban medical care undoubtedly remains the best in the developing world. Indeed, in many ways, Cuba offers better health care than countries in the developed world—infant mortality rates are lower in Cuba than in the United States, for instance. The same can be said for many aspects of education. That said, the price paid for the (badly needed) reforms has often been high, and tears in the Cuban social fabric can be seen.

A warning note was sounded in April 2011 at the Sixth Congress of the Communist Party

when a series of guidelines were introduced. The document of guidelines that resulted

was introduced by a quotation from Fidel Castro: “The term ‘revolutionary’ reflects

the sense of the historical moment; it means changing everything that should be changed” (emphasis added). Armed with that general philosophy, the document provides 313

guidelines, a common theme of which is the need for the Cuban population to be more

efficient and productive, in essence, to do more with less—even in the traditionally

protected areas of health care and education. Article 143, for example, emphasizes

the need to “continue improving our services in education, healthcare, culture and

sports. In order to accomplish this it is absolutely necessary to reduce or eliminate

excessive costs in social matters, as well as generate new sources of income” (http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/secciones/6to-congreso-pcc/Folleto%20Lineami

entos%20VI%20Cong.pdf). From the government perspective, it is clearly a time for belt tightening and,

in some cases, a reduction of services. Social policy in Cuba is thus being amended

drastically to fit in with Cuba’s economic reality.

As a result, Cuban society has changed in many ways for better and worse. For example, the food covered by the ration book has been reduced significantly, the free lunches offered at the workplace have all but gone, and huge layoffs in the state employment sector have resulted. Subsidized water and power rates have also been reduced. Cubans can now stay at hotels previously reserved for tourists and have cell phones and computers, all of which are sensible changes. The age for retirement has been increased (to sixty for women and sixty-five for men). Bank credits have been provided to Cubans in order to increase food production, repair homes, and support self-employment. In recent times, sturdy Ladas and Moskavich cars, the mainstay of family transportation, are still on the streets of Havana, but increasingly Audis, BMWs, and Mercedes (bearing the conspicuous yellow license plates identifying private ownership) are seen (perhaps that is one of the reasons why a proposal has been introduced to standardize all license plates for cars). Beauty salons and (private) health clubs have now appeared, another novelty, as is Cuba’s answer to Craig’s List—Revolico.com.

Many of the changes are more dramatic, however, and respond to demands that Cubans have been making for years. For the first time in fully five decades, Cubans can now buy and sell houses and cars—a major breakthrough and one that is long overdue. While to people not familiar with Cuba this might appear remarkably normal, what needs to be remembered is that since 1959, Cuba has resolutely pursued a revolutionary socialist model designed to ensure a level playing field for all Cubans regardless of income, color, or geographical location. Prior to the Special Period, for example, Cuban law stipulated that the differential between the highest and lowest salaries in the country should be no more than five to one. That has long since disappeared, with social polarization now resulting from the reforms introduced first in the early 1990s and then strengthened under Raúl Castro. (An illustration of this is the salary of doctors—who earn approximately $30 monthly—compared with chefs in the burgeoning paladar industry who can now earn well over $1,000.) Despite government efforts to reverse the inverted social pyramid, this remains a major challenge. There is also an insidious racial element to the “new” Cuba since remesas, or family remittances (now an estimated $2 billion annually), come largely from white Cubans living abroad and go to their (mainly white) relatives, thus exacerbating socioeconomic differences based largely on race.

In many ways, we now encounter the “Latin Americanization” of Cuba. By that, we mean that Cuba is losing many of its unique characteristics as it assumes aspects of society typically found in all of Latin America. Signs of this are everywhere, from the vendors of pirated CDs and DVDs to the pregoneros who hawk their wares (from food and flowers to brushes and cleaning supplies) with gusto as they stroll down the streets. The large pre-1959 almendrones, private taxis steaming down the principal arteries packed with passengers, seem to have mushroomed overnight and for many are the principal form of transportation. Small mom-and-pop stores have sprung up all over the cities, as have the tiny snack bars (usually found in the doorways to homes). As Sinan Koont shows, there has been a major attempt to revive food production in Cuba (which still imports approximately 70–80 percent of food consumed), with land (up to sixty-seven hectares) being distributed in usufruct to 12,000 would-be small farmers by March 2013. So far, the results are mixed, but the government has clearly indicated that this is an economic priority.

Cuentapropistas, self-employed workers (almost 500,000 strong) who have started their small businesses in recent years, have their signs in front of their workshops and homes advertising their trades. By April 2013, the government had rented more than 2,000 small businesses (such as hairdressers, manicurists, and shoe and clock repair operations) to their employees, who have now started up their own operations. An amazing number of private restaurants, or paladares, have now been established, many of which are in exceptionally luxurious facilities offering high-quality meals. They have multiplied in the past two years, and an estimated 20 percent of self-employed are working in the food industry. Significantly, whereas they were initially limited to a maximum of twelve clients, it is now common to find larger ones catering to several dozen people. An infusion of capital from visiting Cuban American “refugees” (some 500,000 of whom returned in 2012) to family members has understandably fueled this expansion. In February 2013, I had supper at a paladar in the Vedado district of Havana—and was the only foreigner among over fifty clients, a telling illustration of how Cuba has changed in recent years. Likewise, in the spring of 2013, I was struck by the large number of Cuban Americans and their island-based relatives staying at five-star tourist hotels. This was inconceivable just five years ago.

Cuba under Raúl Castro is indeed changing rapidly and mainly (but not completely) for the better as the government seeks to revamp the system, injecting a greater efficiency and vitality. This process is not without major challenges, however. Prostitution, which had largely died down in recent years, has returned, largely as the result of tourism (3 million tourists are expected in 2014) and, to a lesser extent, higher salaries for some in Cuba. Fortunately, there is a limited narcotics problem. Another major challenge is represented by the aspirations of Cuban youth, many of whom were raised during the worst of the Special Period and see only a bleak future with limited prospects. María Isabel Domínguez provides some insightful research into this complex situation. Having seen their parents scrape by during this achingly difficult period, they want something better—and the new migration policy makes leaving an enticing prospect.

More serious is the potential challenge posed by racism, exacerbated by the fact that most of the capital being invested in Cuba comes from (mainly white) exiles, thereby increasing income disparities between white and black Cubans. While 37 percent of the members of the National Assembly in 2013 are black or mulatto, there is the clear need for greater transparency in an analysis of the socioeconomic reality lived by many black and mulatto Cubans, as Esteban Morales argues convincingly. And, of course, the polarization on the basis of income constitutes a major challenge to the revolutionary ethos. In the late nineteenth century, the great Cuban writer and revolutionary José Martí spoke of what he termed the “metalificación del hombre” (literally, the “metalification of people” and the weakening of spiritual values) during his stay in the United States. This referred to the fact that many American citizens cared little for their fellow human beings, instead focusing on the accumulation of wealth. It is a challenge that now needs to be faced in revolutionary Cuba, particularly among the nouveaux riches and also among younger Cubans brought up during the worst of the Special Period—since they know only the grind of the struggle to survive in those exceptionally difficult years. As Domínguez notes in her chapter, the government seeks to encourage Cuban youth to become involved in the process and not to lose themselves in technology and the search for the CUC (the hard currency employed in Cuba).

Access to technology remains a major challenge for the government and, in particular, the underwater cable that Venezuela has provided as a means of improving the connectivity of the island—which has been traditionally hindered by the need to use satellites for Internet access. The cable from Venezuela arrived in 2011, in theory allowing Cuba to overcome its status as the country in Latin America and the Caribbean with the lowest access to the Internet. It is still not being employed fully, with government officials claiming that in keeping with the goals of the Revolution, its priority should be for “social usage” (i.e., schools, hospitals, and so on). So, while access to cell phones has increased dramatically (1.8 million were in use by late 2012), Internet connectivity remains heavily limited. (Meanwhile, opponents of the government, with free access at the U.S. Interests Section and with support from foreign diplomats, have little difficulty blogging.)

In many ways, Cuba under the raúlista influence is taking a major risk, trusting that the population will maintain its support for the revolutionary process as a series of liberal reforms (many of which go directly against traditional government policy) is introduced. These reforms are significant, as this section illustrates, and in many ways represent a potential opening of Pandora’s box—in essence, allowing a minority of Cubans to become extremely wealthy while maintaining the goals of the Revolution writ large and official discourse about equality of opportunity. Perhaps the most important of these changes is the new immigration law allowing Cubans to come and go as they please, leaving the country for up to two years, a policy that has been decades in the making (and that is fraught with risks). This now means that Cubans have greater liberty to travel to the United States than most U.S. citizens do to travel in the opposite direction.

The key term to describe the “new” Cuba is pragmatism, the hallmark of Raúl Castro’s management style for decades in the armed forces, whose role in many areas of Cuba’s economic development—ranging from tourism to agricultural production and marketing to electronics to department stores—has been extremely important, particularly since the onset of the Special Period. It is this approach that has been well channeled into Cuban development since 2006. In addition to the reduction of free or heavily subsidized government services, taxes have also been introduced for the first time since the start of the Revolution. Cubans now pay 15 percent on income of more than 10,000 pesos annually (approximately $400), and this goes as high as 50 percent on incomes of over 50,000 pesos.

This overlying pragmatism is seen in the government’s approach to education and health care, the two jewels in the crown of social reforms in Cuba since 1959. But now there are new challenges facing both social programs, and radically new approaches are being used to make them more relevant to Cuba’s current needs and more efficient. The postsecondary education system is being revamped to encourage the development of graduates better able to contribute to Cuba’s economic development. A significantly reduced number of graduates in the humanities, social sciences, and law has resulted, while far greater attention is now being paid to the training of teachers, agronomists, and tradespeople, as Denise Blum illustrates. Teachers are in particularly short supply, with an estimated need of an additional 1,600. In spite of shortages, Cuba does extremely well in terms of the delivery of its education system. According to UNESCO’s “Índice de Desarrollo de la Educación,” it is the highest-ranking country in Latin America and the Caribbean (ranking nineteen positions above the United States). It also has the highest literacy rate in Latin America and the Caribbean and spends the highest proportion of its gross domestic product on education (13 percent). Yet Cuba is facing a major challenge as the inverted pyramid of income means that it has trouble retaining its teachers—and badly needs to train more.

Likewise in health care, while Cuba has not reduced the number of students of medicine, increasingly they are being encouraged to work abroad (thus bringing in significant funding to the government’s coffers, arguably the largest single source of hard currency). In addition, medical tourism continues to grow apace, and the company Servicios Médicos Cubanos S.A. has been tasked with generating income in Cuba and abroad by selling medical services in a way that has not been considered before. As Conner Gorry and William Keck indicate, this restructuring of the public health care system represents a major change for the body politic of Cuba. It is worth pointing out, however, that despite this process of rationalization, Cuba still enjoys an admirable health profile, exemplified by its infant mortality rate, exceptionally low rates of communicable diseases that are common in many other Latin American countries, and life expectancy that rivals those of the most advanced industrialized countries. The same approach in terms of using the export of professional services to help the national economy can be said, to a lesser degree, of the exportation of Cuban athletic services and indeed Cuban expertise and know-how in general.

One area in which surprising (and very positive) changes have taken place in recent years and one where Cuba stands out as a positive example among its Latin American and Caribbean counterparts is in the area of LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) rights. The role of Mariela Castro, daughter of Raúl Castro and the late Vilma Espín, president for many years of the Federation of Cuban Women, has been crucially important in this campaign, as is indicated by Emily Kirk in her chapter on the contribution of CENESEX (Cuba’s National Center for Sex Education). In addition to Kirk’s chapter, the interview with Mariela Castro provides a useful insight into the goals of this important center as it seeks to turn back the tides of decades of homophobia. These changes and the proposal to change the Family Code (legislation in place since 1975 that outlines a series of progressive laws and responsibilities governing gender relations and issues such as marriage, divorce, and recognition of children) would have been unthinkable even five years ago and illustrate just how much Cuba has changed and is changing.

The status of women in Cuba also continues to develop, and, while the traditional “glass ceiling” preventing women from reaching the upper echelons of power still exists, it has slowly been chipped away at. As a result, it is worth noting that, in terms of political influence, 48 percent of the members of Cuba’s National Assembly are women, and twelve of the thirty-one members of the influential Council of State (including two of the vice presidents) are women. Perhaps most significant of all, fully ten of the fifteen leaders of provincial assemblies are women. Women also make up 65 percent of the professional and technical workforce and represent 72 percent of the workforce in education, 69 percent in health, and 53 percent in science and technology.

The promotion of a new generation of political leaders, the commitment of the president to step down as of 2018, and the appointment of Miguel Díaz-Canel as first vice president clearly illustrate the major changing of the revolutionary guard, as is commented on in the politics section of this volume. But political change among the leadership is irrelevant if the population is not buying in to the larger social project. This section provides some insights into the kind of changes that are being introduced, allowing the reader to appreciate the fast pace of change—for which, in some cases, people have been waiting a long time. These changes are needed since Cuba’s population is slowly shrinking—while its population is gradually aging (18 percent are over age sixty), and there is very little immigration.

In sum, some things in Cuba remain the same. There is the same emphasis on social networks and on access at a remarkably low cost to cultural and sports activities and at no cost to education and health care. High quality in those basic social services—fundamental human rights—remains. In its 2012 report Nutrition in the First 1,000 Days: State of the World’s Mothers, Save the Children placed Cuba in first place among eighty developing countries as the best place to be a mother (and a child). The analysis took into consideration a number of variables, including percentage of births attended by skilled health personnel, risk of maternal death, access to modern contraception, female life expectancy, formal female schooling, percentage of women in national government, under-five mortality rate, percentage of underweight children, and school enrollment. The 2013 report on the State of Mothers in the World placed Cuba thirty-third (of 176) countries—the highest in Latin America and the Caribbean.

There are many criticisms that can be leveled at Cuban society—housing needs are enormous, problems of racism are not being dealt with quickly enough, and machismo is still deeply rooted. Yet what is undoubtedly true is that Cuba is still the country throughout the region where inequality is lower than any other, where more social programs are accessible, where women have the most significant role, where children enjoy the widest range of programs to assist their development, and where greater equality of opportunity can be found. Sadly, this necessary comparative analysis is often lacking when criticisms of Cuba are leveled.

When we prepared the first edition of this book almost a decade ago, we did so because of the significant changes that had occurred, especially in the early 1990s. Now Cuban society has changed radically again, as this section tries to illustrate. As a result, we decided that much of the material found in the earlier edition needed to be updated—so fast has been the transformation since Raúl Castro took over. And, while political leaders in the United States commonly refer to the lack of significant developments in Cuba since that time, they are badly mistaken. It is still unclear where Cuba as a country is going as Raúl Castro seeks a major overhaul—of society, economic structure, and polity. What is absolutely obvious, however, is that change has come and will continue to do so—slowly for many and rapidly for others. The genie is indeed out of the lamp.

María Isabel Domínguez

From the “Special Period” to the “Updating” of the

Economic and Social Model

When we speak of the youth of Cuba, we refer to a segment of the population between fourteen and thirty years of age, according to the definition of the prevailing legislation, although within that definition we can distinguish three groups:

Early youth: between fourteen and seventeen years old

Middle youth: between eighteen and twenty-four years old (the majority in terms of numbers)

Mature or late youth: between twenty-five and thirty years old

In spite of the considerable reduction of youth resulting from the demographic transition that is taking place in Cuba and of the aging of the population, they still represent 20.4 percent of the total population (as of the end of 2011, that meant 2,297,428 young people) (Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información, or Office of National Statistics and Information [ONEI] 2012, 3.3). This situation is the result of increased life expectancy to 77.97 years (ONEI 2012); the sustained low birthrate over past decades, which has not changed since the end of the 1970s (the average number of live births per woman is 1.55 [ONEI 2009a, 67]); and a net negative emigration rate, which has remained between −3 and −3.5 in recent years) (ONEI 2012a, 3.21).

As is the case of the general population, youth are concentrated in urban areas but with a slightly lower ratio (74 percent for youth and 75.3 percent for the total population). In terms of gender, the ratio is 51.5 percent men and 48.5 percent women (ONEI 2012a, 3.3). These figures are important and not only in quantitative terms because of their significance for the present and the future of the nation.

This chapter seeks to analyze some of the main influences on Cuban youth as a result of the economic and social changes in recent years. The youth of today have been born or at least have been socialized during the 1990s in three basic periods, to be examined here:

The 1990s: the economic crisis and its aftermath, known as the “Special Period”

The first decade of the twenty-first century, with the influence of the “Battle of Ideas” and the “New Social Programs”

The current decade: the “updating” of the economic and social development model

Two major factors had a major impact on the life of Cuban youth. One was the intense economic and social transformation experienced by Cuban society in the last decade of the twentieth century as a result of the collapse of the socialist bloc. The other was the strengthening of the U.S. blockade against a society that had initiated a process of rectification of errors in economic management that had lasted over a decade. The economic crisis and recovery had a major impact on society as a whole. Yet these experiences had an even more intense influence on young Cubans at this important formative stage of their lives, especially given the impact it would have on their future development. The crisis itself and the socioeconomic policies designed to overcome it constituted a double-edged sword for the socialization and social integration for this generation of youth in the 1990s.

It is essential to emphasize that, despite the acute economic crisis and the need to rapidly implement measures to ensure an economic and social restructuring in multiple dimensions, even in the most difficult moments there remained a clear commitment to ensure significant social programs, particularly in public health and education. Primary schooling was provided for 99.7 percent of children between six and eleven years of age, while schooling was assured for 92.3 percent of middle school students between eleven and fourteen years of age (92.3 percent) (Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas, or National Office of Statistics [ONE] 1996, 305). Opportunities for free higher education for youth were also protected. That said, there was a decrease in the quality of education among some segments of youth. This was the result of several factors but mainly the devaluation of the national currency. Salaries did not satisfy material needs, making it less attractive for young people to continue their studies, when at the same time other ways of obtaining higher incomes and enjoying a better standard of living emerged. Money was suddenly available through work in the tourist sector, as a self-employed worker, or simply through remittances from relatives abroad.

That combination of factors reduced the proportion of youth studying at middle or higher levels, and this decrease in enrollment strengthened the overrepresentation of women students. For example, in the period 1990–1995, 57 percent of all university students in the country were women, including programs linked to technology (different engineering fields), agricultural sciences, and other specialties, such as physics and computer science. In the 1996–1997 school year, they made up 60.2 percent of students (ONE 1996, 298). The result of this process at the education level was reflected in the increasing feminization of professionals in the labor market. By 1996, women constituted 60 percent of the total number of technicians in the country (ONE 1996, 116).

High levels of vocational training for women also had implications for the family because, among other factors, this professionalization of women has resulted in higher demands in seeking a partner and in the sharing of family responsibilities. As a result, marriage is often postponed, and the number of single women has increased, with a corresponding decrease in the number of children born. All these processes produced changes in Cuban youth in terms of both their role in society and their personal interpretation of that role.

The gradual economic recovery of the country and a clear understanding of the causes of this intense crisis for both society and Cuban youth resulted in a new stage of social development from 2000 on. The objective was to increase opportunities for human potential, and as a result, strategic objectives, as well as social policies, designed to improve the quality of life for the Cuban population were implemented (Domínguez 2010). This gave rise to the New Social Programs, an important part of which sought to achieve the integrated general formation of new generations. They combined the acquisition of knowledge with a range of ethical, cultural, and political values, all of which depended on a revamped educational program.

The importance of this can be seen in the fact that education constituted the largest category of expenditures within the state budget (in 2005, it reached 25.7 percent of total expenditures) (ONE 2006, V.4), and in just five years (2001–2006), it grew by 2.5 times (ONE 2007, VI.4, 160). The main programs implemented in the education field include the following:

Massive training for emergency primary and middle school teachers to cover the deficit of teachers in these areas.

A reduction in the number of students per classroom, to twenty in primary education and fifteen in high school with the goal of providing more personalized attention.

Changes in curriculum, with the introduction of computer science and audiovisual programs at all levels of education and with a guarantee of technical support through the provision of televisions, computers, and video players to all schools.

The creation of courses to overcome youth’s alienation from study and work, with payment to the students and with the opportunity to continue their studies in higher education. This resulted in the graduation, in just the first two periods, of more than 100,000 young people. Of those, a third enrolled in higher education.

The distribution of higher education to all municipalities, with the creation of municipal or satellite university campuses. Together with seventeen universities and another fifty-eight colleges, there were also 3,150 university satellite campuses functioning (ONE 2007, XVIII.5, 351). This concept of universal higher education allowed, in just five years, university registration to grow by 3.8 times, giving rise to the largest number of university students in the country’s history (ONE 2007, XVIII.19, 365).

The creation of the municipal university campuses, as well as allowing expanded enrollment, which helped modify the social composition of the university student body, increasing educational opportunities for all sectors of society, especially for young people from social groups with limited possibilities. This was intended to counteract the reproduction of social inequalities that had been occurring in society as a result of insufficient university capacity and a lack of meritocratic mechanisms to provide access to higher education. The expansion of educational opportunities resulting from the creation of these municipal campuses permitted an increase in the number of university students who were children of laborers as well as a higher proportion of blacks and mestizos.

In addition to institutionalized education, other educational possibilities aimed at children and youth were strengthened, such as the following:

Two new educational television channels were created (“University for All”) to deliver specialized programs in different subjects, including foreign languages.

The Joven Club de Computación y Electrónica (Computer and Electronics) extended its programming to all localities to help provide a computer culture to the community, with priority given to children and young people. By 2005, there were approximately 600 of these clubs with an annual average growth of eighty-two centers since its creation in 2000, distributed in the 169 municipalities and with a graduation of more than 150,000 young people in their regular courses (ONE 2006, XIX.13).

Editorial production dedicated to children and young people increased. Between 2000 and 2005, the publication of children’s books grew ninefold and for youth eightfold (ONE 2006, XIX.2).

In general, this new stage meant the gradual recovery of the value of education and its centrality (understood as the degree of importance attached to it in a person’s life) for most Cuban youth. This was accompanied by the recognition of access to education as a great opportunity provided by society, and in terms of the aspirations of Cuban youth, it once again grew in importance.

As a result of the educational programs, the number of youth alienated from social activity was significantly reduced, and many rejoined the workforce. At the same time, massive access to higher education, along with its undeniable significance as an expansion of opportunities for different social sectors, also generated contradictions regarding the quality of education with certain inequalities between traditional educational spaces in regular courses and new areas of academic interest. In addition, course offerings at the municipal level were concentrated in the humanities and social sciences, with the highest enrollment in areas such as law, social communication, sociocultural studies, sociology, and psychology. The large number of young graduates in these disciplines did not find sufficient employment, so it has subsequently been necessary for them to specialize further.

Since 2010, Cuba has seen the modernization of the economic and social model, which has as its objectives “to guarantee the continuity and irreversibility of socialism, the economic development of the country and the improvement of the quality of life of the population, combined with the necessary development of ethical and political values of our citizens” (Partido Comunista de Cuba [Communist Party of Cuba] 2011, 10). The economic and social guidelines approved at the beginning of 2011 impact the life of society as a whole but have a particular impact on youth and without doubt will provide a challenge to society.

One of the most significant elements of the current process is the expansion of forms of nonstate management of the economy. In the 1990s, for example, the state sector dominated the employment scene. By contrast, in 2010, before the updating of the economic model began, the percentage of workers in the nonstate sector was over 16 percent of the national workforce but just a year later was over 22 percent. In less than a year, the number of self-employed workers grew by 2.7 times, while for women the rate was greater, increasing by 3.3 times (ONEI 2012, 7.2). This growth, which is expected to continue, implies a substantial modification of the occupational and social structure of the Cuban population, although this is not the same throughout the country. For example, 65 percent of self-employed workers are grouped in six of the fifteen provinces of the country—those with the largest cities, such as Havana, Matanzas, Villa Clara, Camagüey, Holguín, and Santiago de Cuba (Trabajadores 2012).

Another challenge for Cuban youth is that the available self-employment work opportunities often do not satisfy their professional expectations because they do not match their qualifications—and they are often overqualified. The recent economic changes introduced by the government thus imply the need for changes in the education system (particularly in terms of technical/professional training) and in particular with the need to restructure university enrollment in order to adapt it to the productive needs of the country. This implies the need for a reduction in enrollment in the humanities and social sciences and an increase in technical and agricultural sciences. For Cuban youth, the combination of these changes in educational opportunities, together with general changes in social dynamics and in economic reforms, may well mean that they will not pursue further education at the university level but instead will train for positions as skilled workers. It will be necessary to watch this process carefully since otherwise it could result in a situation similar to that of the 1990s, when there were divisions based on class and race.

Another important factor that is having a great impact on Cuban youth is the increasing role of socializing processes that occur outside the family and school environment. Among these, there is an important role played by mass media and new technologies of information communication, all of which are reference points for people to develop their concepts of the world. In Cuban society, the mass media belong to the state and are governed by a common communication policy. This makes clearly explicit all regulations over information provided to the people, according to the interests of society. As a result, they have clear guidelines for cultural and educational functions, supporting the set of values that they seek to support. For their part, these new technologies of information communication have entered Cuban social life rather late compared with other parts of the world, and their access has been designed mostly for collective, social uses. Recent studies show that while across Cuba people are in favor of access to these technologies through the technology available in work and educational centers, as well as through the Joven Club de Computación (to provide access to the majority who have no private access), there is a great difference in accessibility to this technology. There is also a digital gap between the capital and other areas of the country in young people being able to access equipment such as DVDs, personal computers, and cell phones.

A final point that is needed in order to have a general overview of Cuban youth today is an analysis of their participation in social activities. It is important to take into account that they are socialized individuals who live within a highly politicized society in which there is a strong network of social and political organizations and associations all of which have huge numbers involved. In other words, they live in a cultural matrix where the sociopolitical component has had a great impact on their worldview and on the way in which they interact within society. Currently, sociopolitical concerns continue to support organizations, preserve their role in terms of public authority and social regulation, and have high rates of participation, but younger generations have been losing interest in them. For example, in studies conducted early in the present century, youth groups identified a set of social opportunities in their lives in Cuba. Among these, sociopolitical participation was listed among the major opportunities offered by the model of society to youth but was not seen as being particularly important in both Havana and the country as a whole.

|

Cuba |

Havana |

|

1. Study 2. Work 3. Health 4. Tranquillity 5. Fun, participation in activities 6. Development of spiritual values 7. Sociopolitical participation 8. Lack of discrimination |

1. Study 2. Work 3. Tranquillity 4. Health access 5. Social justice 6. Sociopolitical participation 7. Recreation |

Source: Domínguez and Castilla (2011).

In Cuba, young people are seen not only as the adults of tomorrow but also as important members of today’s society with their own characteristics: citizens of the present who have influence on others and in a natural, cultural context in which they develop. Therefore, their participation is promoted in and from their own scenarios of social inclusion, especially at school and in the community since it is felt that youth participation is an educational and development tool that will result in benefits not only for themselves but also for the broader context in which they participate. Through this participation, social networks, youth-society relations, and processes of inclusion are developed. This in turn strengthens the possibilities for social connection that participatory practices can create and that also acts as a space for the formulation of youth demands and the promotion of social change.

Youth participation goes beyond the individual level and is organized against the background of a collective society, as part of a whole in which they have roles and functions and a certain degree of commitment. It takes the form of a network of organizations in which social and political activity is carried on within the framework of daily living. The shared objectives are to contribute to an integrated development, a love of country and nature, and to promote participation in cultural movements, sports, recreation, the environment, social work, research, and vocational training and to contribute to economic and social development.

The main school organizations in which young people participate are the Federación de Estudiantes de la Enseñanza Media and the Federación Estudiantil Universitaria. The first includes high school students (grades 10 through 12) who apply to join as well as students in polytechnics and trade schools, so it covers a range of ages between about fifteen years and seventeen to eighteen years. The second includes young people in the university who usually enter at seventeen to eighteen years of age and during the course of their studies participate in activities with other youth with greater experience. This encourages a broad participatory process not only in student tasks but also in broader social and political tasks. In addition to participating in student organizations, from the age of fourteen years, young people participate in various organizations, along with adults, as is the case with the Comités de Defensa de la Revolución (CDR) and the Federación de Mujeres Cubanas (FMC) for females. The latter has played an important role both in educational tasks to support the involvement of adolescents and young people and in encouraging their participation in gender-related activities within the community.

For example, the FMC supported the creation of the Grupo de Educación Sexual (Sex Education Group), which in 1977 joined the Comisión Permanente para la Atención a la Infancia, la Juventud, and Igualdad de Derechos de la Mujer (Permanent Commission for Infancy, Youth, and Equal Rights for Women) of the National Assembly, which in 1989 became the Centro Nacional de Educación Sexual (National Center for Sex Education). They have been involved in matters of sex education, sexual health, and reproduction among Cuban youth (Trujillo 2010, 63) and in recent years have performed extensive work to promote respect for sexual diversity and to combat sexism and homophobia. In 1987, the FMC also supported the formation of the Comisión de Prevención y Atención Social (Commission to Ensure Attention to Social Problems) to provide specialized support for adolescents and young people living in poor social and family conditions as well as those responsible for antisocial behavior (Trujillo 2010, 64).

The experience of youth participation at the local level both in educational tasks and in significant tasks in their neighborhoods and communities has over the years proved to be a contribution to the social integration of their communities. Whereas interaction in student or youth organizations is limited to people of their own age, working in these other organizations encourages intergenerational relationships that extend opportunities for socializing or developing young people’s ways of thinking. In addition to participating in student and community organizations, Cuban youth also participate in a political organization, the Unión de Jóvenes Comunistas (Union of Young Communists [UJC]). Youth can join from the age of fifteen and participate until they are thirty-two. Membership is voluntary and selective. The projection of the work of the UJC goes beyond the interests of its members and focuses on the interests of all young people. Its main objective is the integral and multifaceted formation of the younger generations (Somos Jóvenes 2011) and the promotion of training for political participation.

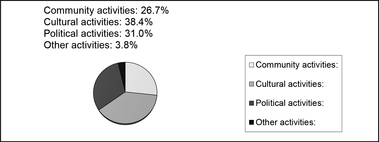

In addition to student and youth organizations that all young people can join, there are others with more specialized interests. Such is the case of cultural organizations such as the Asociación “Hermanos Saiz,” which is for young people with interests in cultural matters, and the Brigadas Técnicas Juveniles (Young Technical Brigades), which young technicians join in order to develop their creative and innovative capacities and promote their work. In a study conducted in 2009 (Domínguez and Castilla 2010) in four of the fifteen municipalities in Havana (Centro Habana, Plaza, Marianao, and Guanabacoa), all with different socioeconomic and sociocultural levels, 55 percent of those who were studying at various levels belonged to student organizations, and 27.2 percent overall belonged to the UJC. In addition, while most young people spent their time mainly in student and labor centers, most (64.6 percent) also participated in various activities in their communities. These activities are shown in figure 37.1.

Community activities mentioned included voluntary work to clean up the neighborhood and to participate in the meetings of neighborhood organizations (CDR and FMC), where topics of interest to residents are discussed. Cultural activities included a wide range of activities linked to music, festivals, dancing, street theater, folk music, and so on. Political activities included participation in marches, elections, commemorative events, discussions of current affairs, and other activities, mainly games and sporting events, carried out in the communities. The majority of young people identified the existence of opportunities for cultural and political participation in their communities, such as their own social and political organizations and the Casas de Cultura (cultural centers), which include places for amateur musicians to practice and workshops for artistic and literary creation and for improving the neighborhood in general (known in Spanish as talleres de transformación integral del barrio).

In summary, in the Cuban context, there is a dense network of formal organizations that encourage the participation of youth and favor their inclusion and contribution to social and political goals. However, the sociodemographic characteristics of the population and, in particular, the aging of society constitute one of the major challenges in terms of intergenerational relationships and continuity of the sociopolitical project. In addition, the economic changes that are taking place and the growth in communities of self-employed workers create a new scenario for youth participation at the local level and require changes in the organizations that operate there.

One of the major challenges facing Cuban society today—and one of the elements that should guide the design model for the future—is the need to continue to evaluate the impact of the recent changes on Cuban society. In particular, we need to analyze the repercussions of these changes on young people in key areas, such as education, the workplace, access to the new technologies, and participation in social and political matters. We also need to study the way in which this impacts them as individuals and as a generation both to understand the values they share and to guarantee the continuity of this commitment of young people with the construction of a better present and future for the country—including the necessary rupture with the past in order to adapt to the new circumstances.

Domínguez, María Isabel. 2010. “Juventud cubana: Procesos educativos e integración social.” In Cuadernos del CIPS 2009: Experiencias de investigación social en Cuba, edited by Claudia Castilla, Carmen L. Rodríguez, and Yuliet Cruz, 110–27. Havana: Editorial Acuario.

Domínguez, M. I., and Claudia Castilla. 2011. “Prácticas participativas en grupos juveniles de Ciudad de la Habana.” In Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud 1, no. 9. Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Niñez y Juventud (CINDE), Universidad de Manizales, Colombia.

Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas. 1996. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba. Havana: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas.

———. 2006. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba. Havana: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas.

———. 2007. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba. Havana: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas.

Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información. 2009a. Proyecciones de la Población Cubana 2010–2030. http://www.onei.cu.

———. 2009b. Informe de la Encuesta Nacional de Fecundidad. http://www.onei.cu.

———. 2012a. Anuario Demográfico de Cuba. http://www.onei.cu.

———. 2012b. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba. http://www.onei.cu.

Partido Comunista de Cuba. 2011. Lineamientos de la política económica y social del Partido y la Revolución. Havana: Partido Comunista de Cuba.

Somos Jóvenes. 2011. “Unión de Jóvenes Comunistas (UJC). Semana 28 julio al 4 de agosto.” July 29. http://www.somosjovenes.cu.

Trabajadores. 2012. “Ejercen trabajo por cuenta propia más de 387 mil 200 cubanos.” June 28.

Trujillo, Ligia. 2010. Vilma Espín: La flor más universal de la Revolución Cubana. Coyoacán, Mexico: Ocean Sur.

Esteban Morales

In Cuba today, people often think about the question of race. Unfortunately, it is a fact of life. The two issues—both reflecting about race and the very reality of the situation—feed on each other. As a result, it is absolutely necessary to work on these two levels—to understand them and then eliminate racism. Eliminating the physical reality of racism will of course always be easier than uprooting it from people’s thoughts.

This is complicated by the fact that since 1959 the reality we have lived has not contributed to the development of racial stereotypes, discrimination, and racism. The predominant social climate was one in which our society exhibited the characteristics of a society with a new form of production and, along with this new model, different ways of social cooperation. The social project, together with a profound sense of justice, contributed to the development of a national identity that we had recovered, as well as a revitalized cultural identity, strengthened and inclusive. This brought educational and cultural attainments to levels that we had never thought possible. And it succeeded in making us believe that the sins of the past would disappear.

The social impact of the crisis [following the implosion of the Soviet Union] helped us to realize that we are like any other country. Social differences were accentuated, prostitution reappeared, some drugs also appeared, corruption and delinquency grew, the standard of living dropped—and in that context black and mulatto [note that the Spanish original used the term “mestizos”] Cubans began to realize that, even though they had made significant progress, they had not managed to build a society that was sustainable and balanced. Racism reemerged. It had never fully disappeared, nor was it disappearing at the rate that we thought it was. Rather, it had gone into hiding, waiting for the right circumstances to reappear—just like other challenges that occurred with the economic crisis.

In terms of the race question, Cuba had been developing into a model for the world. No other country in the hemisphere had changed as much as Cuba had since the Revolution. In no other place like Cuba had such a policy of social justice developed, nor had racism been dealt with so harshly as was the case in revolutionary Cuba. And yet it now became abundantly clear that it had not been sufficient.

Today all Cubans are equal before the law, but in terms of race we continue to live in conditions that are not equal, unable to take advantage of the opportunities that social policy puts at our disposal. Blacks and mulattoes live in worse conditions, receive the least in terms of remittances from abroad, are the most represented in prison, and have the least opportunities in the new economy and, until recently, were least represented in the political structures of the country.

Some ideas to improve this situation, especially affecting young Cubans, are the following:

Racism and racial discrimination are the result of the limited attention paid to these problems for many years. It was only in the mid-1980s that our leadership realized that we had to make significant changes to the social policies that we had followed until then. It was now important to consider the color of one’s skin and to see it for what it was—a key social variable.

It is necessary to strengthen the cultural and racial identity of the Cuban people, within our national identity.

It is necessary to make changes in our education system at all levels and to strengthen the teaching of history. Education has to be all-encompassing and not just limited to school. In addition, it has to permeate all our media, the family, and indeed all forms of cultural expression.

The study of racial issues should be taught at all levels in our schools. We also need to strengthen the teaching of ethnoracial studies at our universities. In this way we will be able to deal critically with the negative aspects, which continue to encourage racism, as well as racial stereotyping, the “whitening” tendency in our society, and the existing racial discrimination in our country. It is not just a case of providing our students with cultural training; instead, we need to give them cultural training that combats discrimination and racism.

Our system of gathering statistics should be considerably improved so that the color of one’s skin can be taken into account in the socioeconomic data collected. It is not sufficient for us to merely count our population. We also need to register all aspects about their role since one’s color is a significant social variable in a country like Cuba. If we do not take into account this variable, we ignore an important series of indicators that are necessary to provide a true portrait of socioeconomic conditions of Cuba.

Taking into account the color of the respondents’ skin, we need to gather data on matters such as the level of unemployment, the type of employment, income levels, salary, condition of housing, level of marginality, history of family violence, remittance income, access to higher education, internal and external migration, life expectancy, infant and maternal mortality, as well as general mortality rates, retirement rates, access to recreation facilities, domestic facilities, and so on.

Not all Cubans enjoy to the same degree the advantages that are available through the social policy of our system. This can be seen with great clarity in terms of education since it is not the same to come from a family of university graduates as it is from a family of workers or peasants who have no experience with intellectual pursuits. Unfortunately, it is not the same to live in [the pleasant suburbs of] Nuevo Vedado as it is Párraga or Pogolotti [suburbs of Havana with large Afro-Cuban populations].

The idea that “we are all equal” was a slogan used by republican politicians. No, all of us Cubans are not equal. We need to recognize that even though we are all—white, mulatto, black—equal before the law and with the same opportunities in an extraordinarily humanitarian system, we all come from very different historical contexts. These are passed along from generation to generation since in many ways we still are influenced by a colonial and neocolonial history of 500 years. As a result, the only way of eradicating this complex reality is to base our social and political reality on an acknowledgment of the lack of equality that still is found here. As a result, we need to characterize, locate, and provide quantitative data for these inequalities. In this way we will be able to attack them at their very roots.

Cuba is not Sweden or Holland. We are a nation of the Caribbean and with a very particular history. This analysis is not based on a simple desire. Rather, the point to be remembered is that, when we do not faithfully analyze the question of color and racial identity, we are throwing into the wastepaper basket centuries of history. In this way we are in effect ignoring the (ongoing) heritage of colonialism, the effect of which all of us still suffer from.

(Taken from the blog entry by Esteban Morales of September 18, 2011, “Notas sobre el tema racial en la realidad cubana de hoy,” http://www.estebanmoralesdominguez.blogspot.ca/search?updated-min=2011-01-01T00:0... [accessed November 7, 2012].)

In a blog entry found the same month, “Cuba: Raza después de 1959,” Esteban Morales noted, “The principal challenge is to eliminate the ignorance that still exists about racism in Cuba: it is necessary to include more black leaders in our history books, to emphasize the role of key black figures, and to study in depth the history of Africa, Asia and the Middle East. . . . We need to deepen the racial awareness, which is still badly lacking in Cuban society, to stimulate the self-respect of black Cubans, and to ensure that the topic of race occupies the place it rightfully deserves in all levels of Cuban education” (http://www.estebanmoralesdominguez.blogspot.ca [accessed November 7, 2012]).

Previously published in TEMAS 56 (2008). Reprinted by permission of the author.

Tracey Eaton

When Agusto González didn’t have money to buy a television antenna, he improvised, making one out of sticks, a tree branch, a rubber tube, aluminum, and wire. “It may not look like much, but it works,” said González, forty-eight, a coffee grower in Santo Domingo, a village at the foot of the Sierra Maestra, Cuba’s largest mountain range.

Fidel Castro hid out in the Sierra Maestra in the 1950s while planning his revolt against then dictator Fulgencio Batista. I hiked through the same rugged hills to reach La Plata, Castro’s once-secret command post, hidden in the forest. I met González along the way.

His ranch was filled with Robinson Crusoe–style devices. One contraption—made with a bicycle rim, a pulley, nylon string, and a bucket—fetched water from the river, down an embankment about twenty yards away.

“You need something, you invent it,” González said. “That’s how we do things.”

I lived in Cuba from 2000 to early 2005 while working as a correspondent for the Dallas Morning News. And when I think back to those years, it’s the remarkable people I remember the most, not the politics or anything else.

González and his neighbors lived off the land. They cooked over open fires. They farmed their land with oxen because they didn’t have fuel for tractors. They used sticks and branches to make pigpens. They turned old coffee bags into curtains.

Stories of González and other characters endure even as Cuba evolves and changes, moving into the post-Castro era. Some of the people I met while covering Cuba are described below.

Sergio García Macías runs one of Cuba’s most popular eateries, featuring roast chicken that has drawn the likes of Hollywood star Jack Nicholson and former president Jimmy Carter.

In the capitalist world, García would probably be a millionaire, maybe even chicken czar of the Caribbean. But he shrugs at the thought and says he isn’t bitter that the socialist government nationalized his family business decades ago.

“My biggest satisfaction isn’t money. It’s seeing that a customer is satisfied,” he said from his restaurant, El Aljibe, in Havana’s Miramar neighborhood. El Aljibe is among the many Cuban institutions that faded away soon after the Revolution, only to be rescued years later to help prop up the ailing economy. A chicken meal when I met García fetched $12, then the monthly wage for the average Cuban.

García, seventy-three, said he never dreamed his roast chicken would become such a smash. He and his older brother, Pepe, eighty-two, opened their first restaurant, El Aljibe’s predecessor, in 1947. Located in the countryside west of Havana, it was called Rancho Luna.

Their late mother, Toña Macías, came up with the chicken recipe, still secret after all these years. García revealed just two of the ingredients: garlic and bitter orange, which softens the meat. “We started with nothing and did no advertising,” he said. “I was just seventeen. We were very poor. But clients came and the business grew and grew.” Customers soon included Hollywood stars Errol Flynn and Ava Gardner, undefeated boxer Rocky Marciano, and baseball great Stan Musial.

The original Rancho Luna closed in 1961. The elder García went from job to job in the government, handling administrative duties for state-run restaurants. In 1993, a government restaurant chain asked if he would help revive Rancho Luna. He agreed, and it opened as El Aljibe. Word of the famed roast chicken spread, and soon El Aljibe was again drawing crowds, including everyone from director Steven Spielberg to actor Danny Glover. Said García, “This restaurant is my life.”

Baseball is played in 104 countries on six continents, but Cuba is probably the most baseball-crazed nation on the planet. More than a national sport, baseball—or pelota, as it is called—is a religion on the island, and just about everyone is a believer.

To better understand the phenomenon, I went to Havana’s Latinoamericano Stadium.

One of the first people I noticed was a thin, twenty-something woman wearing jeans.

Mileisi Esquijarosa was on the edge of her seat. Then suddenly she stood, and it happened.

She started crowing like a rooster.

“Kikiri ki! Kikiri ki!” she cried as her favorite baseball team, the Sancti Spíritus Roosters, scored against the home team, the Industriales. Esquijarosa wasn’t just a fan. She was a baseball fanatic who took voice lessons to master her ear-piercing call.

I realized it was going to take some time to understand this religion known as baseball. The people at Cuba’s National Institute of Sport, Physical Education, and Recreation hadn’t been much help. Baseball was a delicate topic. Dozens of players had defected to the United States, among them a top-ranked pitching ace, lured by the promise of lucrative contracts. Cuban baseball was slipping into decline, some fans complained. Players endured grueling schedules, crushing economic deprivation, and isolation from the rest of the baseball-playing world.

“The lack of international competition has caused our players’ development to stall,” said Ismael Sené, seventy-three, a former Cuban diplomat and one of the island’s top baseball authorities.

I worried I wouldn’t be able to find players willing to talk to me. Then I found Carlos Tabares, a gregarious, five-foot-seven outfielder. He was captain of the Industriales. He introduced me to other players and invited me to their homes, where I met their mothers, wives, and girlfriends. Tabares told me that players who defected were the exception, not the rule. “We play because we love the sport. We have nothing to do with ‘rented baseball,’ playing just for money. Besides, the government gives us everything we need—a salary, bats, gloves, lodging while we’re on the road, meals. A full buffet.”

Rodolfo Frómeta, head of a militant anti-Castro group in Miami, boasted that would-be assassins shot a former Cuban spy during a 2:00 a.m. gun battle.

I tracked down the ex-spy in Havana to find out if it was true. Juan Pablo Roque showed no signs of injury when I talked to him outside his home in 2003. I asked if he’d been attacked.

“I’m fine,” he said. “Can’t you see?”

That made me suspect the assassination attempt never occurred. But there certainly were people who wanted to do harm to Roque. He had been a spy in Miami and was a key figure in the Cuban military’s shoot-down of two civilian aircraft in 1996. Roque declined to talk about any of that in 2003. He said he didn’t want to somehow hurt the case of five Cuban spies who had been jailed in the United States on espionage-related charges.

I caught up with Roque again in 2012. This time he agreed to an interview.

Roque, a former fighter pilot with Hollywood good looks, didn’t appear desperate but conceded he needed money. He said he was selling his house and a prized possession, a GMT Master II Rolex he bought with money the Federal Bureau of Investigation gave him while he was an informant in Florida.

Roque had staged his defection from Cuba in 1992, swimming to the U.S. naval base at Guantánamo Bay and declaring opposition to Fidel Castro. He became a pilot for Brothers to the Rescue, a group dedicated to searching for rafters in the Florida Straits. But then he stunned everyone in 1996, slipping back into Cuba the day before Cuban MiGs shot down two civilian aircraft flown by members of the exile group.

Now fifty-seven and living with his girlfriend in a cramped Havana apartment, Roque said he was sorry four people were killed in the February 24, 1996, incident. “If I could travel in a time machine,” he said, “I’d get those boys off the planes that were shot down.” The four dead were Carlos Costa, Mario de la Peña, Pablo Morales, and Armando Alejandre Jr.

Alejandre’s sister, Maggie Khuly, said justice was never done. “Speaking for the families, my family in particular, we’re looking forward to the day when Roque faces U.S. courts on his outstanding indictment,” said Khuly, a Miami architect.

A federal indictment charged Roque with failing to register as a foreign agent and conspiring to defraud the United States in May 1999.

Asked about the charges, Roque sighed. He said he believes that the Cuban government was justified in defending its airspace but that he should not be held responsible for the deaths. “I am not to blame. I didn’t do anything wrong. I didn’t order anyone killed. The decision to shoot down the planes was a decision of the sovereign Cuban government. The decision to shoot down the planes was taken because of the constant air incursions, violating airspace.”

Asked if he had any regrets, Roque said he wishes he had done more to stop the shoot-down. “Perhaps now . . . I’d try to play a much stronger role in the things that happened. I’d try to play a better role. If I played it bad or good, let the people decide. Let those who want to judge me, judge me.”

Ana del Rosario Pérez was suddenly in trouble. Her friends had asked her to feed an entire beach party, but she had little more than two eggs and some puffed wheat. So she got creative. “I stirred up the eggs and added salt. I put oil in a pan and started to cook the eggs. Then I started tossing in the puffed wheat. When that was all done . . . I added garlic, peppers, onion, and tomato paste.”

Result: Enough scrambled eggs for eighteen people. And no one knew that wheat was the key to stretching the two eggs, the forty-year-old homemaker said.

Across the island, Cubans routinely whip up culinary concoctions to ward off hunger and make ends meet. They turn potatoes into mayonnaise, peas into desserts, and green plantains into casseroles. “We don’t eat meat every day in Cuba, but no one goes to bed without something to eat,” said Juan José León, a spokesman for Cuba’s Ministry of Agriculture.

The food situation has been critical in Cuba since the fall of the island’s chief sponsor, the former Soviet Union. But many Cubans can’t afford to shop in the stores, where a box of cereal fetches as much as $9.65 and a can of Pringle’s potato chips goes for $3.50. So they work their magic in the kitchen, inventing recipes and turning leftovers into meals.

Variety is the key, said Cristina Ortega, a fifty-two-year-old retiree. “I can’t stand eating the same thing every day.” Among her favorite inventions: cupcake-size casseroles made from plantains. “You peel a green plantain and slice it. Then you fry it, mash it with a glass, and mold it into a little cup with your hands.” She said she fills the cups with whatever she has—ground meat or canned ham, if possible—and tops them with grated cheese. Then she heats them for five minutes, and presto—they’re done.

When Yanet Vázquez finally decided to end her marriage, she and her soon-to-be ex-husband strolled into a notary public’s office, plunked down $4, and were blissfully divorced in twenty minutes. “It was quick and easy,” said Vázquez, thirty-one, a cashier.

Indeed, getting unhitched in Cuba is about as cheap and effortless as it gets. The country’s liberal divorce laws also fuel one of the world’s highest divorce rates. “For every 100 marriages in Cuba, there are almost seventy divorces. It’s alarming,” said María Benítez, a demographics specialist and author of the book The Cuban Family.

The island’s severe housing shortage forces many people to live with their in-laws and other relatives, straining even the best of marriages. Economic conditions also create tension that drives many couples apart, Benítez said. “We have First World health and schooling levels but seventeenth- and eighteenth-century marriage habits,” she said. Some Cubans change spouses every few years. “I’ve split up three times already,” said José Rivero, forty, a musician. “I spent seven years with the first woman, five with the second, and eight with the third.”

Cuba legalized divorce in 1869 and introduced divorces by notary public in 1994. “No other country in the world has this kind of divorce,” said Ayiadna María Verrier, a notary public in Old Havana. Many divorces are not only quick but remarkably civilized. Maricel Acebo, thirty-nine, and her ex-husband, Wilfrido, continued living under the same roof despite their divorce less than a year earlier. “I’m not going to tell him, ‘I want you living out on the street,’” she said. “That wouldn’t be fair.”

One day I decided to write a story about Cuban names. The idea occurred to me while having lunch with Cuban writer Senel Paz and a few other friends. Paz wrote the screenplay for the acclaimed movie Fresa y Chocolate (Strawberry and Chocolate). Over rice, shrimp, and salad, we somehow got onto the topic of names. Paz said his own name is an invention of sorts. His mother named him Senel but probably meant Senen, an established name. But like a lot of Cubans who automatically replace the letter “n” with “l” in their rapid-fire Caribbean speech, she made it Senel. “I don’t know of any other Senels except some of my relatives—and they’re named after me,” Paz said.

“We invent names because we’re looking for originality. I think some Cubans started inventing names to imitate the sound of Russian. People are drawn to exotic sounds.” Indeed, I found Cubans named everything from Yusimi and Yanko to Yusmeli and Yasnara. One Cuban mother named her boy Yesdasi—Yes-da-si—yes in English, Russian, and Spanish. Another came up with Yotuiel. That translates roughly from Spanish as “me, you, and him.”

Cubans sometimes pick names simply because they like the look of them. Scores of children living near Guantánamo, an American military base on the eastern tip of Cuba, are named Usnavy, taken from U.S. Navy. Others are Usmail, from U.S. Mail.

One woman named her son William Guillermo over the protests of her relatives. In English, that’s William William.

Given such combinations, the Cuban government sometimes refuses to allow certain names. But meddling can have unintended consequences, as it did in the case of the mother who wanted to call her daughter María José. María is fine, Cuban officials said, but not José because that’s a boy’s name. Okay, said the mother, who finally opted for Esoj Airam—María José spelled backward. Officials accepted that.

Taking ordinary names and spelling them backward isn’t uncommon in Cuba. Examples include Odraude, from Eduardo; Orgen, from Negro; Leinad, from Daniel; and Susej, from Jesus. One mother toyed with calling her daughter Vivian, but that had no pizazz, no imagination. So she settled on her own creation: Naiviv. “It’s Vivian in reverse,” said Naiviv Trasancos, a travel agent. “I like it. It’s different, distinctive.”

Some parents choose names with a revolutionary flair. “I was named in honor of Fidel,” said Ana Fidelia Quirot, a Cuban track star and Olympic athlete. “I’m very proud of it.” Other Cubans name their children after esoteric military institutions. One couple named their son Dampar, which stands for Defensa Anti-Aerea de las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias (Anti-Air Defense of the Revolutionary Armed Forces). Evidently caught up in revolutionary fervor, the same couple named their daughter Sempi, for Sociedad de Educación Patriótico-Militar (Society of Patrotic Military Education).

Other Cubans have such names as Inra, for the Instituto Nacional de la Reforma Agraria (National Institute of Agrarian Reform); Init, for the Instituto Nacional de la Industria Turística (National Institute of the Tourist Industry); and Pursia, for the Partido Unido de la Revolución Socialista (United Party of the Socialist Revolution).

Devout Catholics sometimes name their children after saints. A calendar showing the saint of the day helps them pick. But things don’t always go right. Some Cuban children, with humble parents still trying to figure out which side of the paper holds the saint’s name, have actually been named Santoral al Dorso: “Saint on Reverse.”

Félix Savón, Cuba’s two-time Olympic heavyweight boxing champion, ultimately went with something safe: He named four of his five children after himself. His two sets of twins are named Félix Mario and María Félix and Félix Félix and Félix Ignacio.

Still other Cubans insist on the unusual. Take the case of Cuban actor Jorge Perugorría and his wife, Elsa. He had always wanted a daughter but got three sons instead. He persuaded her to try one last time, and she had yet another son. Thankful that childbearing was over, she named him Amén.

Sinan Koont

Urban and Suburban Agriculture

One of the most interesting and important developments in Cuba in the past two decades has occurred in its food production and distribution systems. The results of this development include one of the world’s shortest producer-to-consumer chains in fresh produce and the general introduction of agroecological production technologies throughout the island. (Among other characteristics, agroecological practices attempt to minimize the use of fossil fuels, including petroleum, and their derivatives, such as chemical pesticides and fertilizers, in production and transportation.)

Before discussing the reasons for this remarkable and far-reaching transformation and its evolution and consequences, it makes sense to place it in its historical and geographical context. Cuba is an island (albeit the largest) in the Caribbean region and was colonized by the Spanish Empire beginning in the early sixteenth century. After 1958, the new revolutionary government of Cuba, with the help of two Agrarian Reform Laws of 1959 and 1963, nationalized most of the cultivable land in Cuba, until then mainly in the hands of large landowners, both Cuban and foreign. Cuba eventually established an industrial agricultural system based on extremely large state farms active, among other lines, in cattle raising, sugarcane, rice, and citric crops production. The export crop production model was modified but not abandoned.

The state farms were generally unproductive, however. The monoculture cultivation in these large state farms led (as in the Soviet Union) to reduced efficiency and productivity, resulting in smaller outputs and lessened returns on agricultural investment. It was also causing increasing damage to the soil as well as to the environment in general. In addition, industrial agriculture in Cuba was completely dependent on the importation of petroleum (and machinery) from the Soviet Union and socialist Eastern Europe. And since the 1960s, the island had been caught in the cross fire of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. Cuba’s national defense and security organizations could not ignore the possibility of the complete cutoff of the imports of petroleum, machinery, and petroleum derivatives, such as chemical fertilizers and pesticides, making industrial agriculture impossible.