‘“We know your honour will help us again” is the consoling remark with which [the poor] wind up their tale of disappointment and prospective want, and this seems to them, after their late experience [of government intervention in the grain trade], a sufficient security against the risk of famine.’ So Charles Trevelyan was told on 18 August 1846 by Sir Edward Pine Coffin, the commissariat officer in charge of the Limerick depot. Coffin knew that the relief operations of 1846–7 would be conducted very differently from those of the current season, and as if to justify the change, he said of the attitude of the poor: ‘It is a characteristic feeling, but one replete with mischief to themselves and to the community. . . .’1 Before the new relief system could be installed, the old one needed to be terminated, and this could safely be done, it was felt, because the harvest season was about to start. Employment on the public works was gradually reduced beginning in the second week of August. By the end of that month the number of persons earning wages from the Board of Works had fallen to a daily average of 38,000, and it continued to decline for several weeks thereafter.2 (The corresponding figure for the week ending on 26 September was slightly below 15,000.) The food depots also reined back their sales, with a view to a complete cessation of operations at the close of August.

The relief policies of the new Whig administration had been disclosed to parliament by Lord John Russell, the prime minister, in mid-August, when all the available evidence already pointed to a calamitous failure of the potato crop. Russell announced that he and his colleagues were opposed to any general interference by the government with the grain trade. The primary emphasis in any new crisis would be placed less on the sale of food and more on the provision of employment through a revamped system of public works. In adopting these policies, the cabinet was basically accepting the proposals made by Charles Trevelyan. In an important memorandum submitted to the cabinet on 1 August, Trevelyan insisted that ‘the supply of the home market may safely be left to the foresight of private merchants’, and that if it became necessary for the government to interfere at all, its purchases should be restricted to the home market in order to encourage the private importation of food. As anxious as Trevelyan was to allow full scope to private enterprise, he recognised (though not sufficiently) that in parts of Ireland grain importers and retail traders either did not exist or were too few in number to provide adequate supplies in a period of extreme scarcity. Even so, he proposed minimal intervention: government food depots should be set up on the west coast alone, but not even there should they issue food while supplies could be purchased from dealers or obtained from other private sources. In essence, then, the government committed itself to acting as a supplier of last resort west of the Shannon. Everywhere else (around the north, east, and south coasts from Derry to Dublin and Cork, as well as east of the Shannon generally), ministers and relief officials considered themselves bound to a policy of non-intervention, and pledges to that effect were actually given to merchants.3

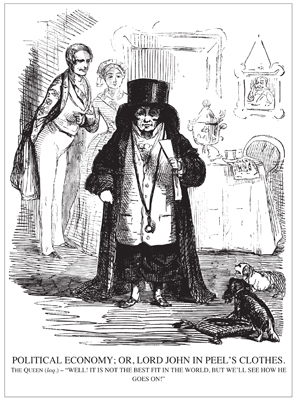

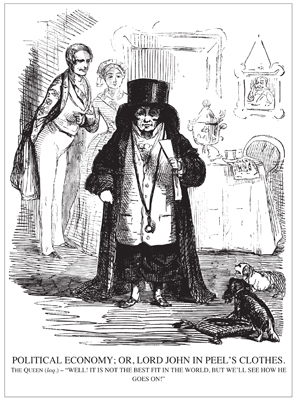

This Punch cartoon of July 1846 – ’Political economy; or, Lord John in Peel’s clothes’ – shows Queen Victoria whispering in the background, ‘Well! It is not the best fit in the world, but we’ll see how he goes on!’ While poking fun at Russell’s small physical stature as compared with Peel’s, the cartoonist was also expressing the widespread doubt that the new prime minister would be the political equal of his predecessor. This doubt was more than justified, especially in relation to Ireland. (Punch Archive)

The partial potato failure of 1845 had allowed the government a period of six or seven months to prepare its relief machinery before having to set it in motion. But the new crisis was utterly different. The almost total failure of 1846 permitted virtually no breathing space before the destitute masses sought to throw themselves on government resources. With respect to food, those resources were shockingly inadequate, even for the west alone. By the end of August all but a few of the depots had closed, and the stocks remaining had dwindled to less than 2,100 tons of Indian meal and about 240 tons of oatmeal.4 When the prospect of a total potato failure became all but certain in August, Trevelyan scrambled to increase official stocks by employing as corn factor the London merchant Eric Erichsen. His initial purchases were quite small, and on 19 September Routh protested to Trevelyan: ‘It would require a thousand tons to make an impression, and that only a temporary one. Our salvation of the depot system is in the importation of a large supply. These small shipments are only drops in the ocean.’5 The problem, as Trevelyan explained a few days later, was that ‘the London and Liverpool markets are at present so completely bare of this article [i.e., maize] that we have been obliged to have recourse to the plan of purchasing supplies of Indian corn which had been already exported from London to neighbouring continental ports’.6 Partly through such expedients Erichsen was able during August and September to buy about 7,300 tons of maize, along with 200 tons of barley and 100 tons of Indian meal.7

These imports, however, did little to raise commissariat reserves because the depots could not be kept shut altogether. The largest issues were made from the store at Sligo, which served the north-west, where acute distress became evident as early as mid-August. Over 650 tons of maize meal and oatmeal were distributed from here alone between 10 August and 19 September. Heavy pressure persisted for many weeks thereafter, and it was not until early November, after the first local arrival of private imports, that relief officials were able to close the Sligo store.8 The combination of small government imports and unavoidable issues from some of the depots caused the total stocks in government stores to long remain well below the minimum level of 8,000 tons that Routh considered necessary before there could be any general opening of the depots in the west. Official stocks did not surpass 4,000 tons until the end of November, and a month later they barely exceeded 6,000 tons.9 Even so, at the end of December the treasury finally consented to throwing open the western depots ‘for the sale of food as far as may be prudent and necessary’.10

Could the government, by prompt action, have secured enough food from Britain or foreign countries to open its depots in the west of Ireland much sooner? It has been suggested that if Trevelyan had been willing to move decisively into the grain market as soon as he received the first reports of the reappearance of blight in mid-July, adequate supplies could have been accumulated. The late T.P. O’Neill pointed out that Trevelyan was urged by Assistant Commissary-General Hewetson in late July to purchase 4,500 tons of Indian meal immediately. ‘This warning had been ignored,’ O’Neill observed, ‘and purchases began too late in the season to ensure the arrival of sufficient quantities before Christmas.’11 But the matter is more complicated. Hewetson clearly did not anticipate issuing the meal until the spring of 1847.12 On the other hand, it is true that Erichsen’s purchases for the government did not begin until 26 August, and that of the 22,600 tons of maize bought through his agency up to mid-January 1847, only about 6,800 tons had actually arrived by that time in Ireland or Britain.13 The government, in fact, had to contend with two serious obstacles. The first was the unavoidable delay of one to three months between the date of purchase and the date of delivery, and the second was that after such heavy imports in the first six or seven months of 1846, Indian corn was in short supply in the London and Liverpool markets as well as on the continent. Trevelyan had ruled out direct government orders to the United States, but even if he had not done so, American maize was not quickly accessible. As Routh noted of the requests forwarded by Irish merchants to America in September, ‘These orders cannot be executed so as to arrive in the United Kingdom before the end of November, and then only the old corn of last year [1845], for the new corn of this year will not be ready for shipment before January.’14 This much may be conceded: if Erichsen had been authorised to begin his purchases in late July instead of late August, there would have been considerably more food in the western depots before the end of 1846; perhaps the stores would have opened a month or so earlier than they did. But this would not have been enough to avert the onset of famine and epidemic disease.

GRAIN EXPORTS ALLOWED

Since relief officials did not expect large supplies of foreign corn to begin to reach Irish ports before December, they were especially anxious to see the domestic harvest brought to market as rapidly as possible. One excuse offered for keeping the western depots generally closed and for not establishing stores outside the west was that this policy would accelerate the process of converting the grain harvest of 1846 into food. It soon became apparent, however, that in spite of steeply rising grain prices at home, exportation on a large, though diminished, scale was once again taking place. Routh was alarmed and more than once hinted at the desirability of stopping it. ‘The exports of oats have amounted since the harvest to 300,000 quarters’, he told Trevelyan at the end of September. ‘I know there is a great and serious objection to any interference with these exports, yet it is a most serious evil. . . .’15 As he remarked in another letter, ‘The people, deprived of this resource, call out on the government for Indian corn, which requires time for its importation.’16 But Trevelyan promptly and brusquely turned Routh’s suggestion aside. ‘We beg of you’, said Trevelyan, ‘not to countenance in any way the idea of prohibiting exportation. The discouragement and feeling of insecurity to the [grain] trade from such a proceeding would prevent its doing even any immediate good; and there cannot be a doubt that it would inflict a permanent injury on the country.’17 Trevelyan’s decision, never questioned by his political masters, seems to have been based more on his rigid adherence to laissez-faire economic doctrines than on a careful assessment of its practical short-term consequences. To have forbidden exports from the 1846 grain harvest might well have led to some reduction in food imports late in 1846 or early in 1847, but it would hardly have paralysed the trade, and it would have helped materially to fill the huge gap in domestic food supplies that persisted until long after the maize ordered from America began to reach Irish shores in December.18 Most scholars would agree that this refusal to prohibit exports, even for a limited period, was one of Trevelyan’s worst mistakes, although the blame was of course not his alone. More than any other single decision, it provided some substance to the later nationalist charge that the British government had been prepared to see a large proportion of the Irish people starve.

Allowing unhindered exportation certainly contributed significantly to the remorseless rise of Irish food prices between September and the end of the year. As long as the wholesale price of Indian meal remained at £10 or less per ton, as it did through August, there was little risk of famine, but as each succeeding month brought higher prices, malnourishment increased, eventually to the point of starvation, and along with it susceptibility to infectious diseases, the greatest scourge of all. At Cork the price of Indian meal rose from £11 a ton at the beginning of September to £16 in the first week of October, and before the end of that month it stood as high as £17 to £18; only slight reductions (to £16 or £17) were recorded in November and December.19 When food was sold from the depots, as happened periodically before late December, the prices were purposely regulated by those prevailing in the nearest market town or by the current trade prices. This was justified on the grounds that private traders had to be allowed to earn reasonable profits, and that if they were undersold, there would be such a rush to the depots that the limited supplies would quickly be exhausted.

The latter argument contained some truth, but the former displayed, to say the least, undue tenderness for grain importers and dealers, whose profits swelled. Even commissariat officers conceded the point. As Hewetson told Trevelyan in late October, ‘The corn dealers and millers are everywhere making large profits, but I trust [that] Christmas will see prices much lower.’20 Among the biggest beneficiaries were G.W. & J.N. Russell, ‘the great corn factors and millers of Limerick’, who at this time were grinding over 500 tons a week.21 Their prices tended to regulate the cost of food not only in Limerick but also in north Kerry, Clare, and Tipperary. In mid-November Hewetson pressed this firm to reduce its prices and extracted a promise that the charges for Indian meal and oatmeal would at once be lowered to £16 and £20 a ton respectively. Yet ‘even this is too high a figure for any length of time’, and though the firm deserved what Hewetson called encouragement, he feared that if the matter were ‘left altogether to the few houses in the city (theirs giving the tone), reductions will be very gradual in operation’.22 And so they were, without effective government intervention and with ever more doleful consequences. Indeed, the depots actually made substantial profits on their sales: in mid-January 1847 the commissariat was charging £19 a ton (as high as £22 or even £24 ‘in some situations’) for Indian meal that it had purchased a few months earlier for about £13.23 This situation reflected Trevelyan’s inflexible view that unless prices were allowed to attain the full market rate, Ireland would be even worse placed to attract foreign supplies to its ports and to retain within the country what food had been produced there. Or as he said in a little lecture to Routh late in September 1846, ‘Imports could not take place into a country where prices are artificially depressed, but, on the contrary, the food already in the country would be exported to quarters where a fair market price could be obtained.’24 This, needless to say, was to make a religion of the market and to herald its cruel dictates as blessings in disguise.

MASSIVE PUBLIC WORKS

Against this pattern of non-intervention and general passivity with respect to the food supply in late 1846 must be set the burst of activity in the field of public works. It will be recalled that there had been intense dissatisfaction among relief officials with many aspects of the system of public works during the previous season of distress. The new system, devised mainly by Trevelyan in August 1846, was intended to avoid the inefficiency, waste, and extravagance which in the official view had characterised earlier operations. Instead of allowing the county grand juries to initiate and direct a significant proportion of the employment projects, it was decided that the Board of Works should assume complete responsibility for all public schemes. And rather than continue the practice under which the treasury paid half the cost of projects controlled by the Board of Works, it was ordained that in future all charges should ultimately be met out of local taxation. Though the treasury would advance the money for public works in the first instance, the proceeds of county cess were to be used to repay these loans in full. Irish property must support Irish poverty: much was to be heard of this maxim, a favourite of English politicians and civil servants, during the famine years. In sum, then, the government created a system that combined local financial responsibility with thoroughgoing centralised control of employment projects. By design the schemes were not to be ‘reproductive’, since Trevelyan wanted to restrict applications from landowners. This policy was soon modified under pressure from Irish landlords, but the practical results of the alteration were meagre and, in the new season of distress as in the old, the building or repair of roads and bridges was the most common activity. Cutting hills and filling hollows were the main tasks.25

With the assumption of complete control by the Board of Works came the imposition of time-consuming bureaucratic procedures. (The board itself was on the verge of becoming a mammoth bureaucracy, with 12,000 subordinate officials.) Only the viceroy himself could authorise the holding of an extraordinary presentment sessions, and the relief schemes proposed at the sessions had first to be scrutinised by the board’s officials, who then might request the treasury to sanction them. Adherence to these procedures caused agonising delays in starting public works, not only when the new system was inaugurated but also, to some degree, throughout its whole duration, since at any given time, while some works were being closed, others were being opened. Delays, however, were particularly numerous at the outset. The viceroy had ordered public works to be restarted early in September, but it was not until October that the new schemes began.

Even though the problem of delay was never eliminated, the sheer pace and scale of operations soon became quite extraordinary. Indeed, the extension of the bureaucratic apparatus could hardly keep pace with the headlong expansion of employment. Between the first and the last week of October the average daily number of persons employed by the Board of Works soared from 26,000 to 114,000; throughout November the figure climbed steadily, reaching 286,000 in the fourth week. Though the rate of increase slowed somewhat during December, 441,000 persons had crowded on to the public works by the end of the year. The peak was reached in March 1847, when during one week as many as 714,390 persons were employed daily. Naturally, the expenditure was great. By the time that the system of public works was terminated in the spring of 1847 and replaced by the distribution of free food (in a terribly belated confession of failure), the accumulated costs of these relief schemes amounted to the staggering sum of almost £4,850,000. It could now be said that Irish property was paying, or rather was beginning to pay, for Irish poverty.26

FATAL INADEQUACY OF WAGES

Enormous as the expenditures were, they had not been nearly sufficient to bring enough food within the financial reach of the rapidly increasing masses of destitute people. The fundamental problem was the inadequacy of the wages paid on the public works. Beginning in September 1846, the Board of Works tried to substitute a system of task labour for the daily wages that had prevailed previously. The main reason for this drastic change in policy was to eliminate or at least to reduce the general indolence that had allegedly prevailed among labourers during the past season of relief operations. The board instructed its officials that ‘the sum to be paid for each portion of [task] work should be sufficient to enable an ordinary labourer to earn from 10d. to 1s. per day, and a good labourer who exerted himself, from 1s. 4d. to 1s. 6d. per day’.27 As a punitive incentive designed to win acceptance for task work, those labourers who were unwilling (or unable) to do it were to be paid no more than 8d. per day.28 This was from one-fifth to one-third less than previous daily rates for customary unmeasured work, even though food prices were already rising when the reduction was ordered.

The introduction of task labour was fiercely resisted by the workers, often to the point of violence, and many projects had to be stopped, at least temporarily, before popular opposition could be overcome. Officials tended to attribute the resistance they encountered to the labourers’ unfamiliarity with task work or to their unreasonable fears of unfair treatment if they consented to do it. But there were serious practical problems, only too evident to the labourers, which the higher officers of the board were inclined to minimise or overlook. Any delay in the setting out of task work, and delays were unavoidable in view of the rapidly growing scale of operations, meant (or was supposed to mean) that wages had to be paid at the low daily rate of 8d. On the other hand, when task work was set out but not measured immediately, as was usually the case, the labourers were paid on account, the rule being that they were to receive three-quarters of the agreed value of the assigned work, for example 9d. on account for a task worth 1s. Delays in conducting measurements, occasioned by the shortage of qualified staff and by other factors, frequently caused severe hardship, and there were complaints that payments on account fell short of the stipulated three-quarters.29

Another reason for popular opposition to task work was that the scarcity of implements had the effect of seriously reducing wages. Many labourers assigned to task work in the closing months of 1846 were unable to earn even half the ‘ordinary’ rate of 10d. to 1s. because they lacked the proper tools. Among one gang of seventy-five men in the Cong district of Mayo there were only two wheelbarrows, two crowbars, and a wooden lever. The few possessing these implements received up to 10d. a day while the rest earned as little as 31⁄2d. to 4d. Labourers whose task work once entitled them to 1s. a day but whose health declined were later unable to claim more than 6d. while toiling at the same job.30 Indeed, the system of task labour operated to the general detriment not only of the sick or infirm but also of the old, women, and adolescents. Some labour gangs excluded individuals in these categories from their ranks because the presence of such people would have lowered the rates of wages that physically strong and healthy adult males could earn.

To judge from the reports of the inspecting officers of the Board of Works, however, a majority of workers in many districts eventually came to accept and even to approve of task labour. To many, it offered or seemed to offer the possibility of adjusting their wages to keep pace with the rapid advance of food prices; it was particularly attractive to younger adult males in sound health, who could thrive under this system or at least avoid being engulfed in the rising sea of misery around them. Another reason for acceptance or approval was that workers were often able to turn the system more to their advantage. Local overseers of the public schemes in numerous districts were subjected to great pressure by the labourers to exact less work for a given rate of wages than the application of strict standards would have required. Harsh overseers risked being beaten, and the fear of assault (along with humanitarian feeling, in many cases) inclined overseers to leniency in enforcing standards. Higher officials of the Board of Works complained that there was widespread collusion to raise wages between their subordinates and workers engaged in task labour. Early in December the head of the Board of Works, Lieutenant-Colonel Harry David Jones, told Trevelyan: ‘I am quite convinced from reading our last week’s reports and from other sources that our task system is not working as it ought to do; the men are receiving much larger sums than they ought to do. . . . I believe everybody considers the government fair game to pluck as much as they can.’31

Yet the sad truth was not that too many earned too much, but that too many earned too little to enable them to ward off starvation and disease. A signal defect of the task work regime was the growing physical debility of many labourers suffering from malnutrition, a condition which made it impossible for them to earn the sums of which ‘ordinary’ workers were considered capable. In west Clare, for example, debilitated labourers were seen to stagger on the public works at the outset of 1847, and ‘the stewards state that hundreds of them are never seen to taste food from the time they come upon the works in the morning until they depart at nightfall . . .’.32 Barely more than a month after telling Trevelyan that task work wages were too high, Lieutenant-Colonel Jones had to admit that the opposite was often true: ‘In some districts the men who come to the works are so reduced in their physical powers as to be unable to earn above 4d. or 5d. per diem.’33

In many parts of the country where public works had been opened, task labour had not been introduced at all, or had been only partially adopted, or had been abandoned after a period of trial. In numerous instances the nature of the work to be performed or the character of the terrain was considered unsuitable for the adoption of task labour. In other cases the subordinate officials of the Board of Works were incapable of shouldering the additional technical and supervisory burdens associated with task labour. ‘It is extremely difficult to carry out the board’s wish respecting task work,’ remarked the inspecting officer for north Kilkenny in late December, ‘the nature of the soil being so different in various places that nothing like a fixed list of prices can be established, and the overseers are not capable, in most instances, of measuring and valuing excavations, &c., were the staff of the engineers sufficient to overlook the works properly.’34 The board itself pointed out in mid-January 1847 ‘the impossibility of finding overseers qualified to estimate and measure tasks for 10,000 separate working parties’.35 In the many localities where day labour remained the dominant or exclusive form of public employment, wages were even more likely to be inadequate to sustain health than in areas where task work prevailed. It is true that the rule limiting payment by the day to 8d. was not always scrupulously observed, but the wage for this type of work rarely exceeded 10d., and such sums condemned the recipients and their families to malnutrition and disease.

This became a common complaint in the weekly reports of the inspecting officers beginning in December 1846, though other commentators had called attention to the general insufficiency of earnings much earlier. From one inspecting officer in County Leitrim came the report that ‘the miserable condition of the half-famished people is greatly increased by the exorbitant . . . price of meal and provisions, insomuch that the wages gained by them on the works are quite inadequate to purchase a sufficiency to feed many large families’.36 Another inspector in County Limerick declared, ‘I greatly fear that unless some fall shortly takes place in the rate of provisions, a great proportion of the families now receiving relief on the public works will require additional support, and that without it they will not long exist.’37 Because the retail price of meal in County Limerick was as high as 2s. 8d. per stone, one labourer from a family of six or more could no longer furnish himself and them with enough food, obliging the inspecting officer to allow a second member of such families to be placed on the public works. (From other counties there were reports at this time of even higher retail prices for maize meal: 2s. 10d. per stone in Galway, 3s. in Meath, and up to 3s. 4d. in Roscommon.)38 A month earlier (at the end of November), the inspector of north Tipperary, where Indian meal was much cheaper (2s. 2d. a stone), remarked, ‘The country people are generally in the greatest distress. Tenpence a day will, I believe, only give one meal a day to a family of six persons. . . .’39 A west Cork observer made a similar calculation early in January 1847: ‘Indian and wheaten meal are both selling at 2s. 6d. per 14 lb; at this rate a family consisting of five persons cannot, out of the wages of one person, say 6s. per week, have even two meals per diem for more than four days in the week.’40 Almost everywhere 8d. a day was literally a starvation wage for the typical labouring family, and so too, in most places, was 10d. Yet a high proportion of the labourers on the public works throughout the country earned no more than these sums, and many earned less. No wonder, then, that work gangs so often engaged in strikes, demanding at least 1s. a day, that overseers and check clerks were so frequently threatened or assaulted, and that in the winter of 1846/7 labourers on the works commonly collapsed from exhaustion.

Two other serious deficiencies exacerbated the general inadequacy of wage rates. One was frequent delay in the payment of wages. To this chronic problem several factors contributed: dishonesty or lack of zeal on the part of the pay clerks, who numbered 548 at the beginning of March 1847 (some of them were also robbed); shortages of silver; breakdowns in the elaborate system of paperwork; and the failure or inability of the overseers to measure task work promptly. Delays of one to two weeks were not unusual, and in some districts interruptions lasting as long as five weeks occurred occasionally. When in late October 1846 a labourer named Denis McKennedy dropped dead by the roadside in the Skibbereen district of Cork, with his wages two weeks in arrears, a coroner’s jury declared that he had ‘died of starvation due to the gross negligence of the Board of Works’.41 This was the first in a string of similar verdicts, though not all of them involved alleged interruptions in the payment of wages. Persistent efforts were made to overcome this problem, and delays were reduced in duration, but they could not be eliminated altogether.

The other serious defect was the government’s unwillingness to pay normal wages whenever work had to be curtailed because of bad weather during the winter of 1846/7. When the issue was first discussed in September 1846, the viceroy directed that if labourers were prevented from working by inclement weather, they should be ‘sent home and paid [for] half-a-day’s work’.42 After frost arrived in early December, Trevelyan observed to Lieutenant-Colonel Jones: ‘Now that the hard weather is come, you will, I presume, act upon the rule long ago settled by you with the lord lieutenant, that on days when the weather will not permit the people to work, they will receive a proportion of what they would otherwise earn; this is clearly the right way of meeting the exigency.’43 To pay only half of what was already in many cases a starvation wage was scarcely right, but at least it was straightforward. Yet the Board of Works apparently never gave a clear instruction in this matter to its local officials. Some of them adopted a half-pay standard, but others – indeed, the vast majority – simply allowed the works to proceed. For obvious reasons, labourers in general did not wish to stop working if it meant the interruption of their pay. But in bad weather they were rarely able to earn much. When heavy snow fell in County Donegal in mid-December, ‘the people continued work during the whole time, but could do nothing but break stones’ for low wages.44 At the same stage in King’s County an inspecting officer declared that ‘earnings this week, after measurement, are much reduced owing to the frost’.45 Extremely bad weather in the second week of February 1847 brought about the first reduction in public works employment since the previous October. Because of a heavy snowfall, the number at work fell from a daily average of 615,000 to slightly less than 608,000. But in the third and fourth weeks of that month alone another 100,000 persons crowded on to the works in spite of the cold and the inadequate wages.46

CONFESSION OF FAILURE

Already, however, those responsible for relief policy had reluctantly concluded that the mammoth system of public works must soon cease to be the centrepiece of the battered strategy for warding off starvation and disease. By January 1847 mass death had begun in some localities, and inspecting officers of the Board of Works anticipated heavy mortality ‘within a very short period’ in the counties of Clare, Cork, Galway, Kerry, Leitrim, Mayo, Roscommon, Tipperary, and Wicklow.47 In mid-January the board confessed itself to be near the end of its powers and resources. Its officers, having already fought a losing battle to keep off the works small farmers with holdings valued at £6 or more, could now do almost nothing to limit the constantly swelling mass of claimants for employment. For their inability they castigated the local relief committees, whose only object, declared Lieutenant-Colonel Jones, echoing innumerable complaints by his subordinates, ‘is to get as many persons employed as possible, instead of anxiously endeavouring to keep the numbers as low as the existing calamity will permit’. In rejecting ‘undeserving’ applicants designated as destitute by the committees, the inspecting officers drew ‘down upon themselves and the board all the odium and vindictive feelings of the poorer classes’.48 It was not unknown for inspectors to be denounced to their faces as the authors of starvation.

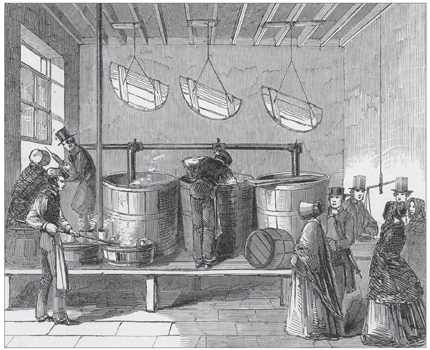

With a long tradition of practical philanthropy behind them, Quakers in England and Ireland responded quickly to the need for direct food relief. The fifty giant soup boilers donated at the outset of 1847 by the famous Quaker ironmasters Abraham and Albert Darby of Coalbrookdale, along with boilers from other sources, allowed the Society of Friends to establish numerous soup houses, such as the one in Cork city depicted in this sketch of January 1847. Altogether, the Friends distributed almost 300 boilers during the famine. Quakers shared many of the reigning economic ideas of the day but were much less likely than others to cling to them in the face of crying human needs. (Illustrated London News)

Even if those deemed undeserving could have been thrown back on their own resources, supposing they had some, the undeniably destitute would more than have filled their places. ‘The number employed is nearly 500,000’, Jones and his colleagues told the viceroy on 17 January, ‘and 300,000 or 400,000 in addition will shortly require it.’49 As many as one-third of those listed as destitute by the local relief committees were still not on the public labour rolls. Even for those currently employed, work to do on the roads was almost exhausted. Indeed, the main roads had been made much worse, not better. Landed proprietors, who had ‘voted thousands and thousands of pounds’ for such schemes, ‘cry out that the great communications of the country are destroyed’, Jones acidly remarked, ‘and I have no doubt that for this season they are all more or less severely injured and many nearly impassable, but whose fault is that? Not ours.’50 His board, he insisted to Trevelyan, could not possibly accommodate the additional multitudes likely to be driven to the public schemes in the coming months by want of food: ‘We have neither staff nor work upon which we can employ them.’51 Even if there were scope for a wide extension of the road projects, the system of task labour could not be retained. ‘The fact is’, Jones finally admitted, ‘that the system . . . is no longer beneficial employment to many; their bodily strength being gone, and spirits depressed, they have not power to exert themselves sufficiently to earn the ordinary day’s wages.’52 Task labour had lost its original purpose, he and his colleagues declared, because ‘the idleness of the idle’ could no longer ‘be distinguished from the feebleness of the weak and infirm’.53 Taking all these circumstances into account, Jones was led to what for him was the distasteful conclusion that ‘it would be better in many cases to give food than to be paying money away, as we are now obliged to do’. Like many others, he had been deeply impressed by the results of the distribution of soup to the starving by private groups such as the Quakers. ‘You will perceive the great benefits derived from the soup establishments,’ he told Trevelyan, ‘and how very cheap is the preparation.’54 Economy in public expenditure being one of the gods that Trevelyan worshipped, the head of the treasury had not missed the significance of soup. Indeed, he was even ready to displace temporarily another of his idols – the general sanctity of the private food market – to exploit its enormous potential. The distribution of free food by agencies of government in virtually all parts of the country was soon to begin. Needless to say, it was too long in coming, and for thousands too late.

Notes

1. Quoted in Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (commissariat series), p. 15.

2. Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 relating to the measures adopted for the relief of the distress in Ireland, with maps, plans, and appendices (Board of Works series), pt i, p. 76 [764], H.C. 1847, 1, 96.

3. O’Neill, ‘Administration of relief’, pp. 223–4.

4. Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (commissariat series), p. 31.

5. Quoted ibid., p. 80.

6. Trevelyan to Routh, 22 Sept. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 83.

7. Ibid., p. 103.

8. Ibid., pp. 93–6, 265.

9. Ibid., pp. 318, 428.

10. Trevelyan to Routh, 28 Dec. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 425.

11. O’Neill, ‘Administration of relief’, p. 225.

12. Correspondence explanatory of measures adopted, p. 215.

13. Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (commissariat series), pp. 22, 506–7.

14. Routh to Trevelyan, 22 Sept. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 84.

15. Routh to Trevelyan, 29 Sept. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 97.

16. Routh to Trevelyan, 30 Sept. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 104.

17. Trevelyan to Routh, 1 Oct. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 106.

18. Bourke, ‘Irish grain trade’, p. 165.

19. Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (commissariat series), pp. 48, 128, 199, 304, 313, 326, 335, 366.

20. Hewetson to Trevelyan, 23 Oct. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 185.

21. Hewetson to Trevelyan, 20 Oct. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 181.

22. Hewetson to Trevelyan, 18 Nov. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 278.

23. Ibid., pp. 479–82, 506.

24. Trevelyan to Routh, 30 Sept. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 101.

25. This and the next two paragraphs draw heavily on O’Neill, ‘Administration of relief’, pp. 227–34.

26. Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (Board of Works series), pp. 195, 344, 486; O’Neill, ‘Administration of relief’, pp. 232, 234.

27. Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (Board of Works series), pt i, p. 140.

28. Ibid., pp. 68, 150–1.

29. Ibid., pp. 152, 230, 346.

30. O’Neill, ‘Administration of relief’, p. 228.

31. Jones to Trevelyan, 10 Dec. 1846, quoted in Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (Board of Works series), p. 334.

32. Clare Journal, 7 Jan. 1847, quoted in Correspondence from January to March 1847 relative to the measures adopted for the relief of the distress in Ireland (Board of Works series), pt ii, p. 3 [797 ], H.C. 1847, lii, 13.

33. Jones to Trevelyan, 18 Jan. 1847, quoted ibid., p. 17.

34. Quoted in Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (Board of Works series), pt i, p. 442.

35. Commissioners of public works to viceroy, 17 Jan. 1847, quoted in Correspondence from January to March 1847 (Board of Works series), pt ii, p. 14.

36. Quoted in Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (Board of Works series), pt i, p. 445.

37. Quoted ibid., p. 448.

38. Ibid., pp. 441, 444, 446.

39. Quoted ibid., p. 285.

40. Quoted in Correspondence from January to March 1847 (Board of Works series), pt ii, p. 5.

41. O’Neill, ‘Administration of relief’, p. 229.

42. Jones to Trevelyan, 12 Sept. 1846, quoted in Correspondence from July 1846 to January 1847 (Board of Works series), pt i, p. 89.

43. Trevelyan to Jones, 5 Dec. 1846, quoted ibid., p. 299.

44. Quoted ibid., p. 414.

45. Quoted ibid., p. 413.

46. Correspondence from January to March 1847 (Board of Works series), pt ii, p. 189.

47. Jones to Trevelyan, 13 Jan. 1847, quoted ibid., p. 8.

48. Ibid., p. 7.

49. Commissioners of public works to viceroy, 17 Jan. 1847, quoted ibid., p. 14.

50. Jones to Trevelyan, 13 Jan. 1847, quoted ibid., pp. 7–8.

51. Jones to Trevelyan, 16 Jan. 1847, quoted ibid., p. 13.

52. Jones to Trevelyan, 19 Jan. 1847, quoted ibid., p. 18.

53. Commissioners to viceroy, 17 Jan. 1847, quoted ibid., p. 14.

54. Jones to Trevelyan, 19 Jan. 1847, quoted ibid., p. 18.