It was possible for Irish landowners who looked back upon the great famine from the vantage point of the mid-1850s to regard that cataclysmic event as advantageous on balance to their interests. A Kerry proprietor who dined with the visiting Sir John Benn-Walsh in October 1852 crudely went ‘the whole length of saying that the destruction of the potato is a blessing to Ireland’.1 But it was much more difficult for landowners to adopt such a view during the famine itself. Over much of the country the difficulties created by the famine seemed decidedly to outweigh the opportunities which it opened up. The two most serious problems facing landlords, especially in the west and the south, were those of collecting rents and finding the means, out of their diminished incomes, to discharge heavy poor rates and to provide additional employment. Though no landowner is known to have starved during the famine, a substantial number wound up in the special bankruptcy court established for insolvent Irish proprietors in 1849.

Because there were enormous variations, even within the same region, it is dangerous to generalise about the degree to which the rental incomes of landowners were reduced during the famine years. It is essential, however, to distinguish between the fortunes of the larger proprietors and the losses of small landlords, especially those who held only or mostly intermediate interests and were not owners in fee. Two highly important determinants of the rate of collection or default were of course the location of the property in relation to the varied geography of destitution and the distribution of holdings by size on the estate. Whereas many owners of overcrowded estates in the west and the south-west were threatened with ruin because of unpaid rents, their counterparts in the north-east, the east midlands, and the south-east often escaped with modest or light losses. In addition, a great deal depended on whether the proprietor generally let his land directly to the occupiers or to intermediate landlords, commonly called middlemen, who sublet their holdings to smaller tenants and cottiers. For a variety of reasons but especially because it entailed a loss of income and of control over tenant access to land, the middleman system had been under attack from proprietors and their agents since the late eighteenth century. But its eradication was a highly protracted process, lasting much longer on some estates than on others, and not completed in many districts until the famine or even later. A survey of the estates of Trinity College, Dublin, carried out in 1843, showed that there were 12,529 tenants on the 195,000 acres owned by the college in sixteen different counties, mostly in Kerry and Donegal. But less than 1 per cent of these 12,500-odd tenants ‘held directly from the college, while 45 per cent held from a college lessee, and 52 per cent held from still another middleman who was a tenant to a college lessee’.2

GETTING RID OF MIDDLEMEN

For perhaps a majority of the middlemen who had escaped eradication earlier, the famine and the agricultural depression of 1849–52 spelled the extinction of their position as intermediate landlords. They were ground into dust between the upper and nether millstones. Head landlords, having long wanted to oust them and to appropriate their profit rents, generally refused to grant them abatements. ‘I have never made an allowance to middlemen or tenants having beneficial interest [i.e., the benefit of a long lease]’, declared the agent of the Cork estates of Viscount Midleton in February 1852,3 and few agents or their employers departed from this rule: it was either pay up or leave. But to pay up was a tall order. In the typical case the minor gentleman or large farmer who assumed the role of middleman had as his tenants a horde of small farmers, cottiers, and sometimes labourers – the very classes which were reduced to destitution or worse by the famine. When his tenants defaulted in their payments, sometimes in spite of large abatements, the middleman’s profit rent sharply contracted or disappeared altogether, and he himself often fell into serious arrears in discharging the head rent owed to the proprietor. Some intermediate landlords whose profit rents were greatly reduced still managed to meet their obligations to the head landlord, but when they did not, proprietors were usually quick to oust them.

The liquidation of middlemen had been the consistent policy of Sir John Benn-Walsh ever since he succeeded to extensive estates of over 10,000 acres in Cork and Kerry in 1825, and the impact of the famine allowed him to bring the process almost to completion. At Grange near Cork city, as he noted in August 1850, the main middleman ‘got greatly into arrear and I brought an ejectment for £800’, a sum that represented more than twice the annual head rent.4 On Benn-Walsh’s much larger Kerry property three townlands near Listowel were in the hands of a middleman named Leake, whose doubtful legal title and financial embarrassment made him a tempting target for attack. By 1850 Leake ‘was getting into arrear, and in consequence of the distressed state of the country we understood that he had little or no profit out of the farm’, observed Benn-Walsh. ‘We accordingly brought an ejectment, to which Mr Leake took no defence, and entered into possession last July [1851].’5 Among the other middlemen remaining on his Kerry estate at the start of the famine, one was evicted in 1846, the lease of a second expired in 1849 and was not renewed, and a third, noted Benn-Walsh in 1850, ‘has fallen a victim to the times’.6

But while the impact of the famine enabled Benn-Walsh to oust nearly all the surviving middlemen on his estates, it also greatly reduced the income which he derived from his Irish properties. Because he had been methodically removing middlemen long before the famine, when that crisis arrived, he had to contend directly with a mass of defaulting smallholders. This problem was especially acute on his Kerry estate, which was entirely concentrated in the poor law union of Listowel. Destitution in Listowel union was not nearly as bad as in Kenmare or several of the unions in Connacht, but it was still severe. As Benn-Walsh recorded with alarm and dismay in mid-August 1849, ‘since last year the debts [under the poor law] have increased eightfold and the union owes about £40,000. There are now 22,000 paupers on outdoor relief out of a population by the last census of 78,000, now probably 10,000 less.’7 Even though destitution on Benn-Walsh’s own property was probably substantially less than in the rest of Listowel union, he could hardly expect well-paid rents. The combined annual rental of his Cork and Kerry estates in 1847 was £5,317, but, as Benn-Walsh later pointed out, during the famine years his rents were ‘merely nominal’.8 The surviving documentation does not permit any precise estimate of his losses, but to judge from a telling remark made in October 1852, they must have been enormous. The collection of the half-year’s rent then payable had netted only £1,200, and yet Benn-Walsh observed with some glee, ‘this is the best haul I have had since the famine’.9 Allowances to his tenants for agricultural improvements certainly contributed to his losses, and so too did the heavy burden of poor rates, both directly and indirectly. ‘The vice-guardians’, he fumed in mid-August 1849, ‘have already collected all the produce of the butter in rates, and they are prepared to strike another in September to secure the produce of the harvest. The fact is that the landed proprietors are now the mere nominal possessors of the soil. All the surplus produce is levied by the poor law commissioners.’10 The bitter experience of Sir John Benn-Walsh, whose rental income may have fallen by more than half between 1846 or 1847 and 1852, can probably be taken as representative of the fortunes of landowners with a multitude of small direct tenants in regions of acute destitution.

A strikingly more favourable situation existed for another and greater Kerry proprietor, the earl of Kenmare. His huge property in that county was concentrated in the poor law union of Killarney, where the degree of destitution was almost as severe as that in Listowel, and yet Lord Kenmare managed to collect as much as £69,500 out of £81,100, or 86 per cent of the rents due between 1846 and 1850. In his case the explanation is simple: of the twenty-three townlands on his estate in Killarney union, no fewer than nineteen were still in the hands of middlemen as late as 1850, and these middlemen neither defaulted heavily (a rare happening in this region during the famine) nor received any abatement from Lord Kenmare. On all of his property in Kerry in 1850, the earl had only 300 direct tenants – a tiny fraction of the total number of occupiers – and they paid an average rent of almost £56.11

Other proprietors did almost as well as Lord Kenmare and occasionally better, even when they were not so heavily shielded by rent-paying middlemen. On the duke of Devonshire’s great estates in the counties of Cork and Waterford, his agents were able to collect 84 per cent of the total of £359,200 due from the tenants between 1846 and 1853. But his properties, besides having been carefully managed for decades, were favourably situated – around Lismore in Waterford and Bandon in Cork – with respect to the geography of destitution. Even at their worst in 1850 his payments for poor rates and other taxes represented only about 9 per cent of his annual rental.12 A much smaller landowner, Sir Charles Denham Jephson-Norreys, whose estate was centred in and around the town of Mallow in Cork, received as much as 90 per cent of the rents owed by his tenants between 1846 and 1853. Well might his agent tell him in August 1850: ‘Taking everything into account, you have come off well with your tenants. Indeed, you are the only man I know who gets anything like his income.’13 Partly, the reason was that a relatively high proportion of the receipts came from town tenants and the holdings of the rural ones were apparently much larger than average in size. Moreover, the estate was again favourably situated. As measured by poor law expenditures in the year 1847–8 in relation to the property valuation, Mallow had less pauperism than any other union in the county.

But even proprietors in districts with comparatively low levels of destitution could not expect to be as fortunate as Jephson-Norreys if their tenants were not large farmers. The experience of Robert Cole Bowen is instructive in this regard. From his tenants in the counties of Cork and Tipperary, Bowen managed to collect 81 per cent of the rents actually due from 1848 to 1853. But his income was not preserved even as well as this figure might suggest. Over the same period his yearly rental declined by about 14 per cent as tenants failed or were evicted without the prompt reletting of their farms. That numerous tenants disappeared from the rent roll is not at all surprising. On neither his Tipperary nor his Cork estate were the holdings large. On the Tipperary property the average yearly rent payable by the 144 tenants of 1848 was £19, and by the 111 tenants of 1853 it was £23. On the Cork estate the corresponding figure for the 37 tenants of 1848 was £27, and for the 28 tenants of 1853 it was £23.14 To have numerous small or middling tenants spelled substantial losses for proprietors even when, as in this case, their estates lay outside zones of heavy pauperism.

If many landowners in relatively advantaged regions lost between 15 and 25 per cent of their rents during the late 1840s and early 1850s, it is easy to appreciate how badly the proprietors of Mayo, west Galway, and much of Clare must have fared. There the appalling degree of destitution and the extremely small size of holdings combined in a doubly destructive assault on landlord incomes. This combination was at its worst in County Mayo. According to a parliamentary return of 1846, no fewer than 75 per cent of the agricultural holdings in that county were valued at £4 or less for poor law taxation.15 This meant, on the one hand, that the vast majority of tenants there quickly became unable to pay rent, and it also meant, on the other hand, that proprietors and other landlords were responsible for bearing nearly the whole burden of the poor rates. The marquis of Sligo, whose property was concentrated in Westport union, informed Lord Monteagle in October 1848 that for three years he had received no rent from his tenants. Though Lord Sligo undoubtedly obtained at least some money, it must have been only a small fraction of his nominal rental of about £7,200 a year, for in Westport union as many as 85 per cent of the occupiers had holdings valued at £4 or less. As early as March 1848 Lord Sligo owed almost £1,650 to the Westport board of guardians, a body that he served as chairman. This debt he was able to discharge only by borrowing £1,500, thus adding to his already heavy incumbrances, which reportedly cost him £6,000 annually. As he told Lord Monteagle, his dire financial condition placed him ‘under the necessity of ejecting or being ejected’.16

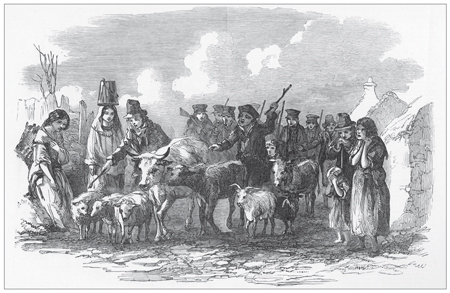

In an effort to collect arrears of rent from tenants unable – or sometimes unwilling – to pay, landlords and agents had long been accustomed to seize tenants’ livestock and to ‘drive’ the beasts to the local pound, where they were held until either redeemed by payment of the arrears or sold in satisfaction of the debt. The proper legal term for this procedure was distraint. This illustration shows the ‘driving’ or distraining of cattle and sheep for unpaid rent in County Galway in 1849. As the overall level of arrears increased enormously during the famine, so too did the practice of ‘driving’. But many tenants took care to sell their livestock or grain before it could be seized. The money thus raised often helped ‘runaway’ tenants to emigrate. (Illustrated London News)

THE CLEARANCES

Evict their debtors or be dispossessed by their creditors – this perceived choice provided a general rationalisation among landlords for the great clearances of defaulting or insolvent tenants that were carried out during the famine and its immediate aftermath. ‘The landlords are prevented from aiding or tolerating poor tenants’, declared the large Galway proprietor Lord Clanricarde at the end of 1848. ‘They are compelled to hunt out all such, to save their property from the £4 clause.’17 Time diminished only slightly the force and currency of this exculpation. In 1866 Jephson-Norreys, the owner of Mallow, was still insisting that the £4 rating clause had ‘almost forced the landlords to get rid of their poorer tenantry’.18 From his experience as a poor law inspector in Kilrush union, Captain Arthur Kennedy (later Sir Arthur) carried away a different perspective. Many years later, he bitterly recalled: ‘I can tell you . . . that there were days in that western county when I came back from some scene of eviction so maddened by the sights of hunger and misery I had seen in the day’s work that I felt disposed to take the gun from behind my door and shoot the first landlord I met.’19

Table 4 |

||||||

Evictions recorded by the constabulary, 1849–54 |

||||||

Year |

Evicted |

Readmitted |

Not Readmitted |

|||

Families |

Persons |

Families |

Persons |

Families |

Persons |

|

1849 |

16,686 |

90,440 |

3,302 |

18,375 |

13,384 |

72,065 |

1850 |

19,949 |

104,163 |

5,403 |

30,292 |

14,546 |

73,871 |

1851 |

13,197 |

68,023 |

4,382 |

24,574 |

8,815 |

43,449 |

1852 |

8,591 |

43,494 |

2,041 |

11,334 |

6,550 |

32,160 |

1853 |

4,833 |

24,589 |

1,213 |

6,721 |

3,620 |

17,868 |

1854 |

2,156 |

10,794 |

331 |

1,805 |

1,825 |

8,989 |

Total |

65,412 |

341,503 |

16,672 |

93,101 |

48,740 |

248,402 |

|

||||||

There was remarkably little resistance and still less shooting. Some large clearances occurred in 1846, but the great campaigns of what were soon branded ‘extermination’ got under way in 1847 as the quarter-acre clause, starvation, and disease loosened the grip of smallholders on their land, and as the mounting tide of poor rates and arrears of rent propelled landlords into frenzied destruction of cabins. The number of evictions for the years 1846–8 can only be estimated very roughly from the records of ejectments, but beginning in 1849 the constabulary kept count of the evictions that came to the knowledge of the local police. In the earliest years of this effort, when estates were being cleared wholesale as well as piecemeal, it is likely that the police figures considerably understated the real total of dispossessions. From the two sets of statistics it is clear that evictions soared in 1847 and increased every year until 1850, when they reached a peak; they remained high in 1851 and 1852 before tailing off to a much lower level by 1854. Altogether, as Table 4 shows, the police recorded the eviction of 65,412 families from 1849 to 1854, but of this number 16,672 families were readmitted to their holdings either as legal tenants (after paying rent) or as caretakers (without payment). Thus a minimum of 48,740 families were permanently dispossessed between 1849 and 1854. The average evicted family included about five members, and the total number of persons dispossessed amounted to almost a quarter of a million.20

This figure, however, does not take account of the ‘voluntary’ surrenders of possession by tenants headed for the workhouse or the emigrant ship, or simply reduced to begging along the roads and especially in the towns. Although such surrenders usually were not reckoned officially as evictions, they often amounted to virtually the same thing, and they were legion. The Kerry and Cork estates of Sir John Benn-Walsh, for example, were ‘very much weeded both of paupers and bad tenants during the famine’. This had been decorously managed by his agent, noted Benn-Walsh in September 1851, ‘without evictions, bringing in the sheriff, or any harsh measures. In fact, the paupers and little cottiers cannot keep their holdings without the potato, and for small sums of £1, £2, and £3 have given me peaceable possession in a great many cases, when the cabin is immediately levelled.’21

LANDLORD-ASSISTED EMIGRATION

Some of the clearances were associated with landlord-assisted emigration. One of the largest such schemes was carried out by Francis Spaight, a famine-enriched partner in the ‘great firm of merchants & corn dealers at Limerick’, after he bought the Derry Castle estate around Killaloe on the Clare–Tipperary border in 1844. Spaight told an obviously impressed Sir John Benn-Walsh in 1849 that he ‘had emigrated 1,400 persons, that this estate was now to be formed . . . into an electoral division to itself, and that he then anticipated that the poor rates would be within his controul [sic] and that the property would be a valuable and improving one’.22 Spaight reported elsewhere that he had spent £3 10s. per emigrant,23 so that the whole operation, which extended over several years, probably cost just under £5,000. An even more far-reaching scheme was undertaken for the marquis of Lansdowne by William Steuart Trench after he became the agent for Lansdowne’s congested estate in bankrupt Kenmare union in south Kerry during the winter of 1849/50. As Trench analysed the daunting situation, some 3,000 of the 10,000 paupers then receiving poor law relief in that union were chargeable to Lansdowne’s property. For the landlord to give employment to so many people, Trench rejected as thoroughly impractical after a short and partial experiment. To maintain them in the workhouse would, he claimed, cost a minimum of £5 per head a year, thus leaving Lansdowne with an annual bill for poor rates of £15,000 when the entire valuation of his property there barely reached £10,000 a year. He explained to Lansdowne that ‘it would be cheaper to him, and better for them [i.e., his pauper tenants], to pay for their emigration at once than to continue to support them at home’.24 Lansdowne concurred, and over the course of three or four years in the early 1850s, slightly more than 4,600 persons were shipped off to the United States or Canada. The total expense exceeded £17,000, and the average cost per emigrant (£3 14s.) was a few shillings more than that incurred by Francis Spaight.25

Perhaps the most notorious episode of a clearance associated with landlord-assisted emigration occurred on the Roscommon estate of Major Denis Mahon and led to his murder in November 1847.26 It was later stated that Mahon, the only large landlord to suffer such a fate in all the famine years, had ejected over 3,000 persons (605 families) before he was slain.27 To a substantial portion of his tenants (more than a thousand), however, Mahon and his agent offered the opportunity of emigration to Canada. They aimed their scheme at ‘those [tenants] of the poorest and worst description, who would be a charge on us for the poor house or for outdoor relief’, and whose departure ‘would relieve the industrious tenant’.28 Ineffective efforts were made to screen out anyone with disease, and a sum of about £4,000 was expended on the passages and provisioning of his emigrants. But unfortunately for his reputation, as many as a quarter of his emigrants perished during the Atlantic crossing, and ‘the medical officer at Quebec reported that the survivors were the most wretched and diseased he had ever seen’.29 Thus the distressing tale of Major Mahon’s clearance became a conspicuous part of the much larger and more dreadful story of the ‘coffin ships’ and the horrors of Grosse Île, or as one contemporary called it, ‘the great charnel house of victimised humanity’.30

By an extraordinary turn of events this clearance and landlord murder became the focus of an extensive journalistic controversy that polarised political and cultural attitudes on both sides of the Irish Sea. In a public letter addressed to Archbishop John MacHale of Tuam and given wide publicity in the English and Irish press, the earl of Shrewsbury, a prominent English Catholic, accused Father Michael McDermott, the parish priest of Strokestown, of having denounced Major Mahon from the altar on the Sunday before he was shot. Shrewsbury demanded that the offending priest be disciplined for contributing to the landlord’s murder. Adding insult to injury, Shrewsbury also observed in his letter that English public opinion held the Irish Catholic church to be ‘a conniver at injustice, an accessory to crime, [and] a pestilent sore in the commonwealth’.31 Fr McDermott produced credible evidence that he had never publicly denounced Major Mahon at any time, but the furore soon broadened to embrace rival English and Irish religious and political stereotypes and clashing images of the Catholic clergy in general. The Nation newspaper in Ireland insisted early in January 1848 that ‘every line that has been written in the English papers for the last two months’ proved that ‘the English charge the whole priesthood with instigations to murder’. ‘Hang a priest or two and all will be right’ was claimed to be ‘the prevalent sentiment in England’.32 In response to Shrewsbury’s public letter MacHale produced one of his own, heaping bitter scorn on the calumniators of the Irish Catholic clergy, vehemently defending priests for their protests against mass evictions, and blasting the Whig government for doing nothing to check the clearances. Indeed, in his much-quoted response MacHale displayed his adherence to the genocidal view of the famine. ‘How ungrateful of the Catholics of Ireland’, he acidly remarked to Shrewsbury, ‘not to pour forth canticles of gratitude to the [Whig] ministers, who promised that none of them should perish and then suffered a million to starve.’33 From the dismal catalogue of tragedies, accusations, and wounds that surrounded the Mahon clearance, relations between the British government and the Irish Catholic church suffered a severe blow, as did landlord-assisted emigration.

Most proprietors who undertook such schemes did so, like Mahon and Spaight, in the years 1846–8, when landlord-assisted emigration was at its height. In contrast to Lansdowne, very few landowners engaged in the practice extensively after 1850. The schemes of these three men, however, were highly atypical in their scale. Oliver MacDonagh has concluded that landlord-assisted emigration from all of Ireland in the years 1846–52 ‘can scarcely have exceeded 50,000 in extent’.34 Since all of Spaight’s 1,400 tenants as well as about 3,500 of Lansdowne’s had departed before 1853, this would mean that these two proprietors alone were responsible for nearly 10 per cent of the estimated total. But like the usually much smaller emigration enterprises of other landlords, those of Spaight and Lansdowne were portrayed as entirely voluntary. Spaight insisted that his tenants left willingly and without rancour,35 and, according to Trench, Lansdowne’s paupers greeted the offer of free passage to any North American port as almost ‘too good news to be true’ and rushed to seize the unexpected opportunity.36 Everyone who accepted, Trench asserted, did so ‘without any ejectments having been brought against them to enforce it, or the slightest pressure put upon them to go’.37 Yet by no means all of those whom landowners assisted to leave were given a choice between staying and going. For a great many, the choice, sometimes implicit and at other times made quite explicit, lay between emigrating with modest assistance and being evicted. Moreover, as MacDonagh has argued, it was a pretence to say that a pauperised tenant without the ability to pay rent or to keep his family nourished had a ‘free’ choice in the matter.

MASS EVICTIONS IN KILRUSH UNION

Yet even if the choice was highly constrained, it was far less inhumane than the total absence of an alternative, which is what the vast majority of estate-clearing landlords offered. West Clare in particular presented in the years 1847–50 the appalling spectacle of landlords cruelly turning out thousands of tenants on to the roadside. This heartless practice first became intense in the winter of 1847/8 and the following spring, as one landlord after another joined the campaign. Furnishing a list of the many cabins unroofed or tumbled on six different properties in just two of the electoral divisions of Kilrush union, Captain Arthur Kennedy informed the poor law commissioners early in April 1848, ‘I calculate that 1,000 houses have been levelled since November and expect 500 more before July.’ Those dispossessed, he declared, ‘are all absolute and hopeless paupers; on the average six to each house! Enough to swamp any union or poor law machinery when simultaneously thrown upon it.’38 Deceit and small sums of money were used to bring about acquiescence: ‘The wretched and half-witted occupiers are too often deluded by the specious promises of under-agents and bailiffs, and induced to throw down their own cabins for a few shillings and an assurance of outdoor relief.’39 Many of the evicted

betake themselves to the ditches or the shelter of some bank, and there exist like animals till starvation or the inclemency of the weather drives them to the workhouse. There were three cartloads of these creatures, who could not walk, brought for admission yesterday, some in fever, some suffering from dysentery, and all from want of food.40

Other dispossessed families crowded into cabins left standing in neighbouring townlands ‘till disease is generated, and they are then thrown out, without consideration or mercy’.41 The larger farmers in the vicinity of these clearances took advantage of them by getting ‘their labour done in exchange for food alone to the member of the family [whom the farmer] employs, till absolute starvation brings the mother and helpless children to the workhouse; this is the history of hundreds’.42 (It is little wonder that Kennedy wanted to take his gun and shoot the first landlord he met.)

Such was the scale and intensity of the clearances of 1847–50 within its bounds that Kilrush union eventually acquired a gruesome notoriety throughout Ireland and Britain that was similar to that held earlier by the charnel-house district of Skibbereen. Kennedy’s relentless drumbeat of criticism thoroughly antagonised the local landed gentry and their agents. Some of them vigorously contested the statements and eviction statistics presented in Kennedy’s reports to the poor law commissioners in Dublin, especially after portions of this information began appearing in newspapers and became the basis for highly critical parliamentary speeches. Kennedy fought back with a tenacity, resourcefulness, and effectiveness which local landlords and agents found galling. The bitter controversy led to the publication (in the British parliamentary papers) of a large sheaf of Kennedy’s reports and eviction lists, and it culminated in the appointment in 1850 of a select committee of the House of Commons under the spirited chairmanship of the independent Radical MP George Poulett Scrope, a rare and zealous champion of the Irish poor throughout the famine years.43

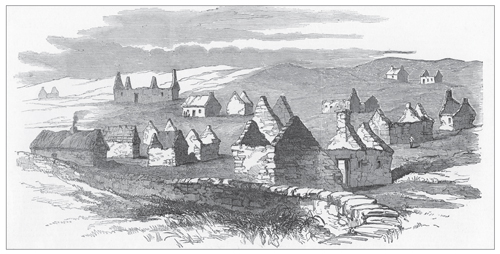

This sketch of 1849 shows the young daughter of the poor law official Captain Arthur Kennedy in ‘her daily occupation’ of distributing clothing to wretched children in the town of Kilrush. Kennedy became poor law inspector for Kilrush union in November 1847 and remained the chief administrative officer there until 1850. Unusually for such an official, he became an increasingly forceful and vocal opponent of the mass evictions carried out by local landlords. The biggest depopulator was Colonel Crofton M. Vandeleur, who evicted over 1,000 persons from his estate. Vandeleur was chairman of the Kilrush board of guardians for most of the late 1840s. He and other local landlords deeply resented and publicly rejected Kennedy’s fusillade of criticism. The controversy attracted much publicity to the Kilrush clearances. (Illustrated London News)

From this controversy a firm picture emerged of the enormity of the destruction wrought by the landlords and agents of Kilrush union. Relying on the notices served on relieving officers and their statements to him, Kennedy told Scrope’s select committee in July 1850 that the total number of evicted persons in Kilrush union since late 1847 amounted – ‘as accurately as I can ascertain it’ – to ‘between 16,000 and 19,000’.44 These figures were contested by Colonel Crofton M. Vandeleur, one of the two largest landowners in the union and for most of the late 1840s the chairman of the Kilrush board of guardians. In his testimony before Scrope’s committee Vandeleur declared that Kennedy’s figure of over 16,000 evicted persons should be reduced by as much as half.45 Also quarrelling with Kennedy’s statistics was Marcus Keane, a man whose enthusiasm for evictions prompted one unfriendly newspaper to say of him that he was ‘unhappy when not exterminating’.46 Though a modest landowner himself, Keane’s great importance derived from his extensive activities as land agent for some of the biggest proprietors in Kilrush union, including the Marquis Conyngham and Nicholas Westby. Altogether, by 1850 Keane exercised sway as agent over ‘about 60,000 acres’, equivalent to nearly 40 per cent of the land area of the union.47 Kennedy had claimed that in nine cases out of ten, when tenants were evicted, their houses were levelled. Yet Keane insisted that on the estates he managed in the union, ‘I have pulled down very few houses.’48 Neither Keane nor Vandeleur was telling the truth.

Their testimony was thoroughly shredded by the painstaking investigations of Francis Coffee, who presented his results to Scrope’s committee in mid-July 1850. Coffee had special and impressive credentials for the inquiry that he conducted. A land agent, civil engineer, and professional surveyor, he was exceptionally well acquainted with the whole area of Kilrush union, having previously revised the poor law valuation for the Kilrush guardians.49 But what made Coffee’s findings so conclusive and so difficult to controvert were his methods of work. His basic source was a set of Ordnance Survey maps showing the exact location of all houses existing in the union in 1841, supplemented by markings indicating all new houses built since that year. Proceeding townland by townland and taking information from relieving officers, land agents, bailiffs, and others, Coffee carefully checked the evidence of his maps against what he could see – or now could not see – on the ground.50 From his exhaustive work he was able to reproduce for the edification of the select committee a detailed Ordnance map, suitably coloured and marked, showing with ‘black spots’ the precise location of the 2,700 instances of eviction identified in Kilrush union. In addition, Coffee’s data distinguished three different degrees of eviction: first, cases in which the affected families had had their houses levelled; second, cases in which families were ‘unhoused’ from a dwelling that was left standing; and third, cases in which families were restored as caretakers. Accompanying this map was a comprehensive list of seventy-six proprietors and middlemen who had engaged in evictions in Kilrush union from November 1847 to 1 July 1850, along with details about the number of families and persons evicted by each, divided into the three aforementioned categories.51

EXPULSION OF 12,000 PEOPLE

Coffee’s cold statistics framed a local story of human distress that stood out boldly even in the endless sea of misery that was the great famine. He found that the houses of 1,951 families had been levelled and that a further 408 families had been displaced (or ‘unhoused’) from their dwellings. Calculating that there had been five people in each of the combined total of 2,359 dispossessed families, Coffee noted with appropriate emphasis that the expulsions amounted to some 12,000 people.52 In addition, another 341 families in a third category, though evicted, had been restored to their houses (if not to their lands) as caretakers. Coffee rightly regarded the caretakers’ position as highly precarious, for they held their houses merely ‘at the will of the proprietor or until their respective tenements were relet to other tenants’.53 Coffee’s data also clearly established the dimensions of the depopulation carried out by Vandeleur and Keane. Vandeleur had dispossessed from his estate as many as 180 families, including just over 1,000 persons – a greater number than any of his landlord peers in Kilrush union.54 Moreover, on the properties which Keane administered as agent, some 500 houses had been levelled. Another 50 families on Keane’s properties had been unhoused, while a third group of 67 families, though evicted, had been allowed to reoccupy their dwellings as caretakers. This was certainly a dramatic and appalling record of depopulation for a single agent. A total of about 2,800 persons had their houses levelled or were displaced from their dwellings on estates in Kilrush union where Keane was in charge.55 Yet in another self-deluded statement before Scrope’s committee in June 1850, Keane could declare, ‘I say that there was more consideration [shown] for the feelings and wants of the poor people who were removed than there was for an increase of [landlord] income.’56

One measure of the intensity of the clearances in Kilrush union is that 17 per cent of its 1841 population suffered some form of eviction between November 1847 and the end of June 1850.57 Clearance and depopulation were greatest in the extensive and once densely settled coastal areas of the union. Speaking of the small coastal holdings stretching from Miltown Malbay down to Kilkee, a distance of 14 miles, Francis Coffee remarked, ‘About three-fourths [of the population] along the coast have been evicted and unhoused.’58 Similar, if perhaps somewhat less savage, events took place in other coastal areas of the union, as on both sides of the peninsula running out to Loop Head.59 Indeed, the worst was over in Kilrush union by mid-1850 precisely because the clearances there had already been carried to such grotesque lengths. Francis Coffee told Scrope’s committee in mid-July of that year that the rate of eviction was likely to slow to less than half of its earlier pace because landlords were now finding that they had carried the clearances too far for their own good. Rates and taxes on evicted lands in the owners’ hands, as well as lost rents therefrom, would, he maintained, ‘reduce their gross income by a very considerable amount’.60

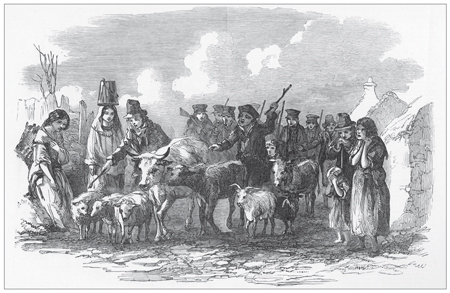

Among the thousands evicted in Kilrush union were Bridget O’Donnell and her children. Her destitution was mirrored in that of the union as a whole. The vast majority of its population were cottiers or landless labourers. Most of the smallholders so densely settled in the long coastal districts of Kilrush union had doubled as fishermen, but the impact of the famine quickly and thoroughly disrupted this customary resource. Fishermen almost universally pawned their nets and parted with their tackle in order to buy food. Unable to pay their rents and standing in the way of ‘agricultural improvement’, they were removed en masse from their little holdings of a few acres. (Illustrated London News)

PRESSURES AND MOTIVES

Who were these Kilrush landowners who executed such enormous clearances, and what were their economic circumstances and motives? It appears that the intensity of mass eviction in this region of Clare was a function, first of all, of the pervasiveness of the mania for clearances among its landlords, from the magnates down to the small fry. Admittedly, the mammoth clearances were the work of a very restricted group. A mere eight Kilrush landlords each dis-possessed more than 400 people and were collectively responsible for almost half of the total of 12,000 unhoused persons recorded by Francis Coffee. Five of these eight actually ousted more than 700 people apiece. Another small group of five landlords each evicted between 300 and 400 persons and collectively accounted for 15 per cent of those dispossessed. The rest of the evicted army (almost 4,600 persons) were the responsibility of the remaining sixty-three proprietors or middlemen on Coffee’s list of seventy-six evictors.61 In this general landlord mania for large-scale evictions in Kilrush union, imitation almost certainly played a significant role, in the sense that the evident ubiquity of evictions there allowed initially hesitant landlords to cast aside their inhibitions and join the common onslaught against small holdings and ‘cottierisation’. Colonel Vandeleur excused the mass evictions locally on the false plea in 1850 that ‘the clearances in our union have been nothing to what I have understood have been the clearances in other unions’ in the west of Ireland.62 Just as Vandeleur invoked the sanction of allegedly greater depopulators elsewhere, so too lesser Kilrush landowners could point to his example as a ready excuse for their own evictions.

The relative poverty of Kilrush landowners was also an important factor in their heavy penchant for clearances. Along with the generality of Clare proprietors, those of Kilrush union must have belonged to the poorer section of the Irish landed élite at the time of the great famine. Admittedly, little of the land of Clare – surprisingly little – was sold during the 1850s in the Incumbered Estates Court, a fact which strongly suggests that crushing indebtedness was not the common condition of the generality of Clare’s proprietors before or during the famine.63 But the structure of landownership in Clare, as revealed by the well-known return of Irish landowners in 1876, giving the acreage and valuations of their estates, is suggestive of quite modest wealth at best. Only four proprietors then had estates in that county larger than 20,000 acres, and even the largest of them, Lord Leconfield’s estate of 39,000 acres, had a valuation of less than £16,600. Edmund Westby’s property of some 27,300 acres, perhaps the largest in Kilrush union, was valued at under £7,900, and in the hands of Nicholas Westby, its owner during the famine years, this estate had an annual rental of about £6,000. Even those Clare landowners with sizeable properties had unimpressive valuations.64 Among the telltale signs of the pinched circumstances of proprietors in Kilrush union during the famine was the extreme dearth of landlord-provided employment. Among the seventy-six landowners and middlemen named in his comprehensive list of Kilrush evictors, there were, remarked Francis Coffee in July 1850, only three ‘who afford what I would consider employment’, and a fourth who furnished some work, but not as much ‘as should be expected from his property’.65 Also conspicuous by its absence was landlord-assisted emigration. Coffee had a short and depressingly stark answer when asked before Scrope’s committee whether many of the 12,000 dispossessed persons in Kilrush union had emigrated: ‘I should say not one per cent.’66

Having in general only modest means to start with, and having in their view little or nothing to spare for such costly projects as employment schemes or assisted emigration, the landed proprietors of Clare and Kilrush union were deprived of much of their rents by the shattering impact of the famine on their tenants, the vast majority of whom were land-poor, with fewer than 15 acres.67 Where there were no middlemen in place to absorb some of the default below them, the losses could be dramatically large. Marcus Keane, whose land agency business covered as much as two-fifths of Kilrush union, told Scrope’s committee in June 1850 that of all the rents due from tenants, ‘I suppose the sum actually received by my employers was about half’. And he said the same thing about the usual experience of the owners of other estates in Kilrush union and Clare generally: ‘About one-half of the amount of the rental was received by the landlords.’68 If Keane was right, part of the reason may well have been that Kilrush proprietors had relatively few middlemen to buffer them against the insolvency and destitution of so many occupying tenants. Keane was adamant that the clearances there did not usually stem from the actions of middlemen or the non-payment of rents to them. On the contrary, he estimated that as many as five out of every six evictions noted in Captain Kennedy’s reports and returns concerned the direct tenants of head landlords, not middlemen.69

Among these direct tenants were swarms of smallholders, as befitted a county whose population had grown at double the national rate and more rapidly than that of any other Irish county between 1821 and 1841. It has been suggested that ‘on the eve of the famine landless or near-landless households accounted for two-thirds of the population of Clare’.70 Kilrush union was an exaggerated version of the county in this respect, as its devastating famine experience demonstrated. Cottier tenants holding fewer than 3 or 5 acres in the coastal district between Kilkee and Miltown Malbay were ‘immediately swept away’ by the successive potato failures of 1846 and 1847.71 Most of the smallholders so densely settled in the long coastal areas of Kilrush union doubled as fishermen, but the impact of the famine rapidly and almost completely sapped the foundations of this traditional resource. ‘Generally’, declared Coffee, ‘five-sixths of those who previously lived as fishermen were obliged to pawn their nets or part with their fishing tackle for their means of subsistence in 1847 and 1848.’72 From the masses of such tenants, landlords and agents could extract very little rental income, if indeed they got anything at all.

On the side of expenditure poor rates were a heavy charge. Admittedly, the rates struck and collected in Kilrush union between 1847 and 1850 were far less than those of many other distressed western unions. A general rate of almost 5s. in the pound (25 per cent of the valuation) was struck in August 1847, but the rates imposed in the following three years were all lower, and that of 1848 was only 3s. in the pound – certainly modest in relation to the extraordinary scale of destitution.73 But for landlords already squeezed by lost rents, the rate burden pinched hard enough, and it seems to have weighed even more heavily on their minds. Marcus Keane asserted that on Nicholas Westby’s estate, with a rental of about £6,000 a year, the rates paid in 1849 had amounted to between £1,800 and £1,900, or almost a third of rents due. Speaking more generally of Kilrush proprietors, Keane observed in June 1850, ‘Their incomes have been greatly reduced, and their charges are so heavy, and the rates so much, that it is with difficulty the proprietors can get money enough to live on.’74 Colonel Vandeleur echoed this gloomy assessment in the following month: ‘I may say that in many instances the landlords have only barely lived.’75

The £4 rating clause of the Irish poor law, which made landowners liable for paying all the rates for holdings on their estates valued at £4 or less, was a source of intense concern, and as elsewhere it impelled Kilrush landlords into mass evictions. The pressure created by the clause, said Colonel Vandeleur in July 1850, ‘has been particularly severe, especially in towns’ – and, he might have added, in the densely crowded rundale villages so common in Kilrush union and rural Clare generally. He cited the case of a street of boatmen, fishermen, and labourers in the town of Kilrush, which he owned. Their forty-nine houses owed a collective rent of £11 14s. a year, but the rates on those houses – all of which he apparently had to pay – amounted to £22 12s. Almost in the same breath Vandeleur pronounced the £4 rating clause ‘a great inducement to get rid of small tenants’ – a conviction which he practised with little restraint.76 In this instance his antagonist Captain Kennedy could not have agreed more with Vandeleur. The £4 rating clause, Kennedy insisted in June 1850, after the avalanche of local clearances had finally begun to abate, ‘induces excessive evictions. The landlord must do it as a measure of self-defence. . . . I think in both cases, whether the rent be paid or not, there is a great inclination to get rid of that class of occupiers.’77

Whatever the real rate burden, fears of being swamped by pauperism probably pushed the landlords and agents of Kilrush union towards clearances. A considerable number of them may have been panicked into starting mass evictions by the gigantic scale of relief in the spring of 1847: as many as 47,000 persons were then assisted under the soup kitchen scheme.78 This was much more than half the total population of the union. And as Captain Kennedy told the poor law commissioners in late February 1848, after the clearances had commenced locally, ‘All who received relief last year . . . naturally expected its continuance and still continue to importune and besiege the relieving officers.’79 Outdoor relief in Kilrush union under the poor law in 1848 and 1849 never attained the level of public assistance granted in 1847; it reached its peak of almost 31,000 people in the summer of 1849 before decreasing to about 9,000 or 10,000 during the winter of 1849/50.80 But in the initiation of clearances Kilrush proprietors were probably moved to such drastic action by the enormous wave of destitution that seemed ready to overwhelm their property in late 1847 and early 1848.

LAW: THE EVICTING LANDLORD’S FRIEND

To expel tenants and level houses on the massive and perhaps unprecedented scale of the Kilrush clearances required landlords and agents to bring to bear a whole complex battery of legal, administrative, physical, and psychological resources before they could accomplish the immense task to which they had committed themselves. Simplifying their task was the fact that clearances could usually be executed with little cost or legal trouble. Where the landowner or his agent aimed to evict any large number of tenants, the cheapest and easiest legal course was to sue for an ejectment on the title in one of the superior courts and to avoid as much as possible the facilities offered by the lower courts – the assistant barrister’s court or the quarter sessions court. The reason was quite simple. In these lower courts each tenant had to be sued separately and at considerable cost – £5 or £6 for the solicitor acting on behalf of the landlord and lessor, according to Marcus Keane, whose vast experience made him an expert in such matters.81 In the superior courts, on the other hand, a landlord could take aim with one ejectment against the tenants of an entire townland, a whole district, or even (in theory) all his property in a given county. As the matter was expressed by Colonel Vandeleur, the biggest of the Kilrush evictors, ‘by civil bill ejectment [in the lower courts] only one party could be included, but by the superior court ejectment you may include as many different parties as you please’.82 Marcus Keane made the same point even more succinctly: ‘You must sue each [tenant] separately in the sessions court, whereas you may sue a whole county in the superior court.’ Every tenant served with a copy of a superior court ejectment who did not resist the proceeding by taking formal defence was ‘liable to be turned out on the issuing of the habere’ [i.e., a decree for possession]. Indeed, as long as the habere was in force, every occupier on the lands could be removed at an hour’s notice.83 This was Keane’s standard procedure, and apparently that of Colonel Vandeleur and most of the other Kilrush evictors as well. ‘I have not resorted’, said Keane in June 1850, ‘to the quarter sessions court in any case [of ejectment], except on one property; I always proceed in the superior court.’84

Among the advantages of the superior court ejectment was the way in which it allowed landowners and agents to weed out those considered bad tenants and to rearrange the farms among the remaining occupiers. ‘What I generally did’, explained Marcus Keane, was to bring the ejectment against all the tenants of a given townland, ‘then take the land from the bad and enlarge the holdings of the good. I had, besides turning out the bad tenants, to remodel the farms and allot to the good tenant the portion it was desirable he should have.’85 What made this practice so attractive to Keane and others like him in Kilrush union was the great prevalence there of the rundale system, with its inefficient scattering of small bits of land belonging to the same tenant in different locations.86 It should be noted that the widespread use of the superior court ejectment as a tool of estate management during the famine years makes it highly problematic to take such ejectments as a measure of evictions, as historians have sometimes done for the years 1846–8, prior to the start of the constabulary returns in 1849.87 Marcus Keane offered a hypothetical example in 1850 in which he said that, using a superior court ejectment, he might evict ten tenants from lands once in the hands of thirty, and then rearrange the holdings among the remaining twenty. In this case what would appear in the records as thirty tenants ejected should really have been only ten.88

UNROOFING AND LEVELLING HOUSES

The wholesale demolition of houses was obviously a special preoccupation of the evicting landlords and perhaps the supreme defining feature of the Kilrush clearances. Marcus Keane, who might be called the greatest of the house levellers, was not bashful about explaining why he and others pursued the practice with such enthusiasm. Partly, it was a device to obviate an immediate risk and its serious financial ramifications. If cabins were not levelled, he told Scrope’s committee in June 1850, ‘you would have the family return again in six hours after they were put out’. And if they did return, ‘you would be obliged to resort to a new ejectment, and in the most expensive court, for you must go into the superior court to prove title in order to expel a pauper who returns and locates himself upon the property’. Such a suit, he claimed, might cost as much as 150 guineas, and he grimly recalled that the large Clare landowner Colonel George Wyndham had been put to the outrageous expense of £200 ‘to get that pauper out of a shed in which he had located himself’.89 But there were other important considerations behind the mania for levelling, tumbling, and knocking down houses. The bigger, solvent tenants – of the kind associated with the much-desired restructuring of the whole agrarian order in Clare and elsewhere in Ireland – were constantly subject to the depredations of the acutely distressed and starving people around them. As Captain Kennedy told the poor law commissioners in February 1848, ‘The farmers complain loudly of the universal pilfering and theft by widows and their children, of which class there is an immense proportion along the coast. A haggard [stack-yard] or garden cannot be left without a night guard.’90 The attitudes of the bigger farmers and their perceived needs heavily influenced the way in which land agents like Marcus Keane approached the conduct of clearances. He made the farmers’ viewpoint his own. ‘Every respectable farmer in the country’, he declared in June 1850, ‘is obliged to keep watch over his effects at night; that is the case throughout the whole of the county Clare.’91 Unless such farmers were protected from these constant depredations, they would abandon their lands and leave the country. To guard against that calamity, the houses of a great many paupers simply had to be levelled. Though he claimed to have avoided knocking down houses wherever he could, ‘there are districts where, if the houses were not levelled, the produce of the whole farm would go to the paupers. When people become poor, they very often become dishonest, to supply the very calls of nature; and when they are scattered about upon the townlands, they have more opportunities of exercising their propensities.’92 Keane asserted that he worked in accordance with certain rules or principles in deciding whether or not to level paupers’ houses. If the continued presence of the paupers would have prevented the land from being ‘occupied by anyone else . . . , as a matter of course, I removed the paupers [and their houses]; but where I thought the presence of the poorer people would not prevent the profitable use of the land by others, or prevent others from taking it, I left them in their houses’.93 To judge from the total of some 500 houses reportedly levelled on estates which he managed, as against fewer than eighty evicted tenants restored as caretakers, Keane’s application of these rules can only be described as draconian.

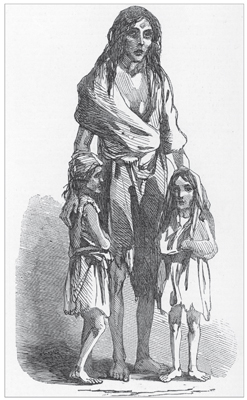

The mass evictions in the poor law union of Kilrush in County Clare were probably unprecedented in their scale and intensity. Belatedly, they were brought to the notice of the British reading public. Just as Skibbereen became horribly familiar through a series of never-to-be-forgotten sketches early in 1847 in the Illustrated London News, so too the Kilrush region commanded similar attention in 1849–50 when the same periodical published numerous haunting images relating to the clearances and their lethal effects there. A careful investigation disclosed in mid-1850 that since November 1847 alone, over 14,000 persons (from 2,700 families) had been evicted from their holdings in Kilrush union. Whole villages were cleared, including that of Moveen, depicted in this illustration. (Illustrated London News)

Those evicted tenants who did not seek or gain the shelter of the workhouse lived precariously. Many reportedly crowded into inhabited dwellings on the same property from which they had been dispossessed. But landlords and agents usually took stern measures to discourage the provision of long-term shelter by occupying tenants. Marcus Keane was said to have given orders that any occupier on the Marquis Conyngham’s estate who gave shelter to an evicted tenant and his family should at once be distrained for the ‘hanging gale’, that is, the half-year’s rent that was commonly allowed to stand in arrears. Moreover, Captain Kennedy asserted that it was ‘usual throughout the union [of Kilrush] to do that’.94 And it is highly probable that in this regard Colonel Vandeleur’s attitudes and conduct were also typical of Kilrush landlords and agents. In a printed notice sent in April 1850 to the ratepayers of Kilrush electoral division, Vandeleur warned ‘all persons holding small tenements under me’ to harbour no vagrants or pauper families in their houses under pain of the penalties specified in their agreements. He observed in the notice that every pauper allowed to settle in Kilrush electoral division might add £4 a year ‘to your rates’.95

Chased in this way from their old estates, perhaps most evicted tenants erected makeshift accommodation for themselves and their families by the roadside, in the bogs, or on pieces of waste ground where they hoped to be left unmolested – a vain hope in numerous instances. Scrope summarised the position well in the draft report of his select committee. Evicted families, he observed, ‘perhaps linger about the spot and frame some temporary shelter out of the materials of their old homes against a broken wall, or behind a ditch or fence, or in a boghole (scalps as they are called), places totally unfit for human habitations . . . ’.96 Against severe cold or heavy rains scalps and similar ramshackle dwellings obviously provided little protection, and such inclement weather, often combined with disease and the denial of outdoor relief, would eventually drive the dispossessed (if they had not died first) to the workhouse as a last resort, in spite of their detestation of the place.97 But squatters in such temporary dwellings might also simply become the targets of a new round of burnings, tumblings, or levellings engineered by remorseless landlords or agents. Under all these circumstances eviction in Kilrush union was very often a death-dealing instrument. Captain Kennedy gave the only truthful answer when he was asked in July 1850 if house levellings had been ‘greatly destructive to life’ during the past three winters. His firm answer: ‘It greatly induced disease and death. I think that cannot be doubted.’98

But dedicated evictors like Marcus Keane and Colonel Vandeleur could not bring themselves to see or speak the truth. Vandeleur was asked in July 1850, ‘Was there much sickness and mortality amongst the class of persons who were ejected?’ Deflecting responsibility, he responded: ‘Not that I am aware of.’99 Questioned as to the fate of evicted tenants, Vandeleur gave a less than truthful reply to Scrope’s committee. ‘They have’, he averred, ‘generally obtained relief from the board of guardians.’100 Marcus Keane also shielded himself from the excruciating reality. When pressed by Scrope to say what became of evicted tenants, he answered: ‘I do not know of any great change having taken place in them since their eviction.’ Destitute before being ousted, they were destitute still, he declared.101 What presumably made it much easier for Keane and Vandeleur to hold such views about the almost ‘benign’ human consequences of mass evictions was their deep conviction that the clearances were absolutely essential to both the economic improvement of the country and their own financial well-being. ‘It would have been utterly impossible’, insisted Vandeleur in July 1850, ‘that the country could have progressed, or that improvements could have been carried out, or that either rates or rent could have been paid in the union if ejectments had not taken place.’102 Keane put this economistic doctrine even more succinctly: ‘In fact, I think the evictions, and driving paupers off [the] land, were absolutely necessary to the welfare of the country.’103 This was exactly the kind of justification, self-evident to its exponents, that allowed most of the depopulators of Ireland to conceal from themselves the enormity of their crimes.

The eviction mania so evident in Kilrush union from 1847 to 1850 was prevalent throughout most of Clare during and immediately after the famine, even if not on quite the same scale. A greater number of permanent evictions occurred in Clare in the period 1849–54, relative to the size of its population in 1851, than in any other county in Ireland. For that period as a whole its eviction rate was 97.1 persons per thousand. Altogether, nearly 21,000 people were permanently dispossessed in Clare from 1849 to 1854, according to the constabulary returns. Thus a county that comprised only 3.2 per cent of the population of Ireland in 1851 experienced 8.3 per cent of the total number of officially recorded evictions between 1849 and 1854. The eviction rate for Clare was even much higher than that for nearly all the other western counties. The corresponding rates for Kerry and Galway were 58.4 and 65.3 per thousand respectively, although for west Galway alone the rate of dispossession was much closer to that for Clare.104

CLEARANCES IN MAYO

Only in Mayo were evictions almost as numerous, relative to population, as those in Clare. From 1849 to 1854 over 26,000 Mayo tenants were permanently dispossessed, a figure which represented a rate of 94.8 persons per thousand of the 1851 population. With only 4.2 per cent of the inhabitants of the country, Mayo was the scene of no less than 10.5 per cent of all evictions in Ireland during the years 1849–54. But the temporal pattern of the clearances in Mayo was strikingly different from that in Clare, the rest of Connacht, or indeed the rest of Ireland. Whereas the total number of evictions in Ireland declined sharply after 1850, the toll in Mayo remained remarkably high during the early 1850s. Permanent dispossessions were more numerous there throughout the years 1851–3 than in 1849 and dropped below the level of 1849 only in 1854.105 Part of the reason for this difference between Mayo and the rest of Ireland, it has been argued, is that Mayo landlords had less cause to engage in clearances before 1850 because a much higher proportion of the tenants there, 75 per cent of whom occupied holdings valued at £4 or less, surrendered their tiny plots to the landlords in order to qualify themselves for poor law assistance.106 In addition, Mayo provided a much higher than average share of insolvent proprietors to the Incumbered Estates Court, and there is an abundance of evidence that the new purchasers of these properties actively engaged in extensive evictions during the early 1850s.107

But even by long-established proprietors, and before 1850, there were some enormous clearances in Mayo, with entire villages of smallholders being erased from the map. Among the greatest of these depopulating landlords was the earl of Lucan, who owned over 60,000 acres. Having once said that he ‘would not breed paupers to pay priests’, Lord Lucan was as good as his word. In the parish of Ballinrobe, most of which was highly suitable for grazing sheep and cattle, he demolished over 300 cabins and evicted some 2,000 people between 1846 and 1849. Some of those dispossessed here may have been included among the almost 430 families (perhaps 2,200 persons) who, as Lucan’s surviving but incomplete rent ledgers show, were ‘removed’ between 1848 and 1851. In this campaign whole townlands were cleared of their occupiers. The depopulated holdings, after being consolidated, were sometimes retained and stocked by Lord Lucan himself as grazing farms, and in other cases were leased as ranches to wealthy graziers.108

Also belonging to the ‘old stock’ of Mayo proprietors who cleared away many tenants was the marquis of Sligo. His policy, he claimed in 1852, was rigorously selective. Though ‘large evictions were carried out’, only ‘the really idle and dishonest’ were dispossessed, while ‘honest’ tenants were ‘freed from all [arrears] and given [land] at a new, fairly valued rent’. Once he had finished implementing this policy, he thought that perhaps one-quarter of his tenants would be forced to leave. Despite his earlier assertion that his was a case of ‘eject or be ejected’, Lord Sligo had a troubled conscience about his evictions. He despised more indulgent landowners, such as Sir Samuel O’Malley and his own cousin G.H. Moore. He professed to be convinced that by refusing to evict for non-payment of rent, they were pursuing a course that would ultimately make necessary clearances far greater in scope than his own. To prove his point, he cited the fact that the indulgent O’Malley was eventually forced to evict on a large scale: on O’Malley’s property in the parish of Kilmeena near Westport ‘the houses are being levelled till at least half [the tenants] are evicted and legally removed’. He severely upbraided Moore, saying that he would become ‘a second Sir Samuel’. In concluding his shrill, self-exculpatory letter to Moore, Lord Sligo declared, ‘In my heart’s belief you and Sir Samuel do more [to] ruin and injure and persecute and exterminate your tenants than any [other] man in Mayo.’109

But while the old stock of Mayo proprietors did a fair share of the ‘extermination’ for which landlords were assailed in the national and local press, they received a strong helping hand in the early 1850s from the numerous new purchasers under the incumbered estates act. Quite a few of the new owners had in fact invested their money in the west of Ireland on the explicit understanding that the property which they were buying had already been or was in the process of being cleared of superfluous tenants. As the prospectus for the sale of the Martin estate in the Ballinahinch district of Galway delicately put the matter,

The number of tenants on each townland and the amount of their rents have been taken from a survey and ascertained rental in the year 1847; but it is believed many changes advantageous to a purchaser have since taken place, and that the same tenants by name and in number will not be found on the land.110

When new owners discovered that the contrary was true, they secured special court injunctions for the removal of such tenants, or they simply proceeded to oust the unwanted occupiers themselves, sometimes avoiding formal evictions by persuading the tenants to accept small sums as inducements to depart. Among the numerous new Mayo purchasers who behaved in one or another of these ways were Edward Baxter at Knockalassa near Cong, Captain Harvey de Montmorency at Cloongowla near Ballinrobe, Joseph Blake on the Abbey Knockmoy estate, and Lord Erne at Barna near Ballinrobe. Similar scenes – the succession of new landlords followed by the eviction of the old tenants and the consolidation of their holdings into much larger units – were occurring during the early 1850s in west Galway and parts of adjacent counties, where among the clearance-minded new owners were John Gerrard at Kilcoosh near Mount Bellew, Francis Twinings at Cleggan near Clifden, and James Thorngate on the Castlefrench estate.111 ‘In the revolution of property changes’, observed the Roscommon Journal in July 1854, ‘the new purchaser accelerates the departure of the aborigines of the country, by which he seems to imagine he has not only rid himself of their burden but enhanced the value of his property.’112

These clearances in Mayo and west Galway set the stage for a considerable expansion of the grazing or ranch system there during the 1850s. Both the old proprietors who escaped the Incumbered Estates Court and the new owners avidly promoted the grazing system. Many of them retained at least part of the depopulated holdings in their own hands and, like Lord Lucan, stocked the land with cattle and sheep. But they also leased recently cleared tracts to new settlers, a substantial number of whom were of Scottish or English origin and set themselves up as graziers on a large scale. The land agent Thomas Miller estimated in 1858 that as many as 800 English and Scottish farmers had secured leases of large holdings in Mayo and Galway, which were almost exclusively devoted to the raising of livestock. Miller indicated that there were particularly heavy concentrations of new settlers in the districts of Hollymount, Newport, and Westport in Mayo as well as around Ballinasloe and Tuam in Galway.113 In a few cases the new settlers were the victims of agrarian violence, but the vast majority escaped any immediate retribution, as did the proprietors who facilitated their entry into the western countryside. Yet the local resentment against these intruders from England and Scotland remained strong for decades and would eventually erupt into violence during the various phases of the land war in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Like the clearances themselves, their beneficiaries were remembered with a poisonous, ineradicable hatred.

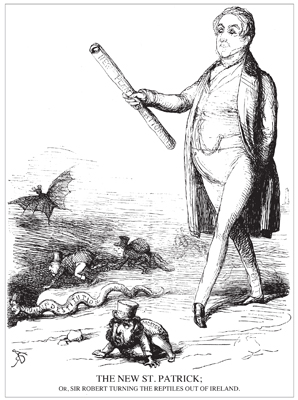

The extreme destitution of the west became a much-discussed political topic in Britain early in 1849, when there were calls for a ‘new plantation of Connaught’, championed especially by the Conservative leader Peel. Radical structural change under government auspices, with new landlords and tenant farmers from England and Scotland introducing large-scale capitalist agriculture on the British model, was seen by some as the only, or the best, permanent answer. Not everyone agreed, as suggested by this Punch cartoon of 17 March 1849 entitled ‘The new St. Patrick; or, Sir Robert [Peel] turning the reptiles out of Ireland’, which ridiculed the notion of a ‘new plantation’. Whigs objected not to the desired outcome but rather to the implied costs and scale of such government-led social engineering. (Punch Archive)

CONSOLIDATION OF HOLDINGS

Through the great clearances of the late 1840s and early 1850s, as well as through mass emigration and mass death, Irish landowners were able to achieve their long-desired objective of the consolidation of holdings on a large scale. The painstaking work of P.M.A. Bourke convincingly demonstrated that the statistics on farm size appearing in the 1841 census cannot be used to gauge the degree of consolidation that took place between 1841 and 1851. The two most serious flaws of those statistics for comparative purposes are that in 1841 farm size was overwhelmingly expressed in terms of the larger, Irish acre (the equivalent of 1.62 statute acres), and that in the computation of farm size waste land was excluded in 1841. ‘Together’, declared Bourke, ‘the two factors led to a reduction of about one-half in the apparent farm size’, in contrast to the real picture that would have emerged if, as in 1847 and later, the statute acre had been taken as the invariable unit of measurement and waste land had been included along with pasture and arable.114 Though it is possible to reconstruct the 1841 figures by applying some rough corrections to those data, Bourke found it preferable to use in a modified form the returns on farm size compiled in 1844 or 1845 by the poor law commissioners. These returns are not fully comparable in all respects with the figures which appear in the annual series of agricultural statistics beginning in 1847, but the discrepancies are relatively minor. The results of Bourke’s reworking of the poor law returns, together with the official statistics for 1847 and 1851, are presented in Table 5.115

Table 5 |

||||||||

Changes in the distribution of holdings by size in Ireland, 1845-51 |

||||||||

Year |

1 acre or less |

1-5 acres |

5-15 acres |

Over 15 acres |

||||

(no.) |

(%) |

(no.) |

(%) |

(no.) |

(%) |

(no.) |

(%) |

|

1845 |

135,314 |

14.9 |

181,950 |

20.1 |

311,133 |

34.4 |

276,618 |

30.6 |

1847 |

73,016 |

9.1 |

139,041 |

17.3 |

269,534 |

33.6 |

321,434 |

40.0 |

1851 |

37,728 |

6.2 |

88,083 |

14.5 |

191,854 |

31.5 |

290,404 |

47.8 |

% change, |

||||||||

1845-51 |

-72.1 |

-51.6 |

-38.3 |

+5.0 |

||||

|

||||||||

The discarding of the 1841 census data on farm size results in making the change effected by the events of the famine ‘less sensational’ but nevertheless quite striking. The number of holdings in the two smallest categories of size declined between 1845 and 1851 by almost three-quarters and by slightly over one-half respectively, and even holdings of 5 to 15 acres fell in number by nearly two-fifths. Farms above 15 acres increased modestly in number between 1845 and 1851, and rather dramatically in proportional terms – from less than a third of all holdings in 1845 to almost a half by 1851. There was never again so sudden and drastic a change in the structure of landholding in Ireland as that which occurred during and immediately after the famine. Though consolidation continued in the post-famine generations, it was usually a very gradual and piecemeal process. Furthermore, for the 50 per cent of Irish tenants whose holdings did not exceed 15 acres, there were severe limits to the gains that could be conferred even by a long period of agricultural prosperity like that of 1853–76, and such tenants of course remained highly vulnerable to the effects of economic downturns on their precarious condition.

INDEBTED LANDLORDS AND THE LAND MARKET

In undertaking clearances of pauper tenants, landlords proved to be pitiless creditors, but they too had creditors who became equally remorseless in pressing their claims during the famine. A lavish style of living assumed before 1815 and not easily supportable under the conditions of depressed markets and lagging rents in peacetime, together with defective laws which permitted the accumulation of debts far beyond the value of the security, meant that even before the famine a substantial section of the Irish landed élite was in a precarious financial condition. In fact, a significant number of heavily indebted landowners were past rescue. In 1844 receivers appointed by the Court of Chancery were administering as many as 874 Irish estates with a combined annual rental of almost £750,000.116 The owners of some of these properties were simply minors or mentally incompetent, but most of them were bankrupts. Under different circumstances these insolvent proprietors might have satisfied their creditors by selling all or part of their estates. But because of further defects in the law, especially the great difficulty and cost of tracing the incumbrances in separate registers in different courts and in the Registry Office of Deeds, prospective purchasers were extremely wary of buying Irish property. Many estates of bankrupts continued under chancery administration for years (some for decades), and thus the backlog of insolvent landowners was very slow to be cleared. From such proprietors tenants obviously received little or no assistance during the famine.

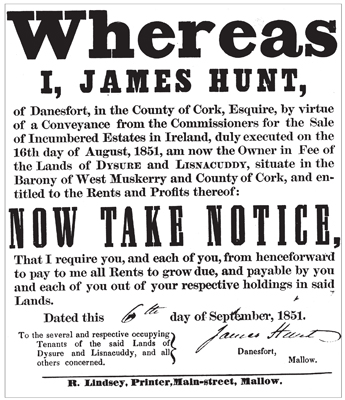

The famine deflated Irish land values, and the passage of the incumbered estates act in 1849 made the decline even steeper, creating an unprecedented buyers’ market. Like most new buyers, James Hunt already belonged to the Irish landed gentry. By paying only 11 years’ purchase (i.e., 11 times the annual rental), he got a great bargain when he bought these 530 acres in the Mallow district of Cork. He issued this notice in September 1851 so that his new tenants would be in no doubt about where to pay their rents. The avalanche of land sales in the early 1850s was concentrated in the west and the south, generally matching the incidence of distress, but sales were relatively rare in Kerry, Clare, and Leitrim, all of which acutely felt the impact of the famine. (Author’s collection)

The great famine had the short-term effect of exacerbating the extreme sluggishness of the land market. On the one hand, it added substantially to the number of bankrupt and acutely embarrassed proprietors. Lost rents, heavy poor rates, and (in some cases) significant expenditures for employment erased what was for many a narrow margin of safety between income and outgoings even before 1845. Foreclosure notices and execution warrants soon began to rain down upon the heads of landowners unable to discharge the claims of mortgagees, bond holders, annuitants, and other creditors. As early as December 1846 one newspaper reported that ‘within the last two months twelve hundred notices have been lodged in the Four Courts to foreclose mortgages on Irish estates’.117 Certain proprietors known to be embarrassed were hounded from pillar to post. Against Earl Mountcashell ‘execution upon execution was issued . . . until in December 1849 there were in the sheriff’s hands executions to the amount of £15,000’, and others in 1850 soon brought the total to about £20,000.118 The earl derived some temporary relief from the fact that his son Lord Kilworth was then the high sheriff of County Cork, and the agent of his estates there was the sub-sheriff, but other landowners in similar straits were not even that lucky.

On the other hand, the famine and the agricultural depression of 1849–52 had the result of greatly lowering the value of Irish land. According to one reliable report, the average rate of sale had fallen from 25 years’ purchase of the annual rental before 1845 to only 15 years’ purchase by the spring of 1849.119 Even though financially embarrassed proprietors needed to sell at least some property to stay afloat, they were generally unwilling to let it go at so great a sacrifice, and therefore they themselves were not about to initiate such ruinous transactions. Even creditors might not wish to force sales in cases where there was reason to fear that the proceeds would not be sufficient to discharge their claims in full because of a low sale price. Yet unless prices were low, and unless secure titles could be obtained, it was difficult to imagine that purchasers would be forthcoming, since the immediate prospects for reasonable returns on their investments were anything but attractive.

THE INCUMBERED ESTATES COURT