L.M. Cullen has argued that the great famine ‘was less a national disaster than a social and regional one’.1 This provocative statement has the merit of drawing attention to the wide social and regional variations in the incidence of famine-related destitution, mortality, and emigration. But to hold that the famine had the character of a national calamity is a defensible position, especially if one considers the combined effects of both excess deaths and emigration on the population levels of individual counties. Only six of the thirty-two counties lost less than 15 per cent of their population between 1841 and 1851. In another six counties the population in 1851 was from 15 to 20 per cent lower than it had been a decade earlier. Of the remaining twenty counties, nine lost from 20 to 25 per cent of their population, while eleven lost over 25 per cent between 1841 and 1851.2

Since the intensity of excess mortality and levels of emigration often differed in individual counties, it will be best to consider these two matters separately. With respect to mortality, both the overall magnitude and the regional variations are now known with some statistical precision. The geographer S.H. Cousens did the pioneering work on this subject. Cousens based his calculations mainly on the deaths that were either recorded on census forms in 1851 or reported by institutions, though he had of course to derive estimates of ‘normal’ death rates before and during the famine. His calculations for each of the thirty-two counties yielded a country-wide total of excess mortality amounting to 800,645 persons for the years 1846–50. Cousens also suggested that the inclusion of the excess deaths that occurred in the first quarter of 1851 (census night was 31 March) would raise the total to approximately 860,000.3 For more than two decades historians were content to regard Cousens’s estimates as generally reliable.

More recently, however, Cousens’s dependence on the 1851 census data has been sharply and effectively criticised by the economic historian Joel Mokyr. His chief objection is to the serious undercounting of deaths in the census, a deficiency arising from the fact that when whole families were obliterated by mortality or emigration, there was no one to report the deaths in such families to the census takers. Cousens was in fact aware of this problem, but his attempt to offset it must now be regarded as insufficient. Adopting a different approach, Mokyr calculates excess death rates as a residual for each county (and for the country as a whole) by comparing the estimated population of 1846 with the officially reported population of 1851 after first accounting for births, emigration, and internal migration. As he frankly admits, the results of these elaborate calculations are not free from ambiguities and possible sources of error. The chief uncertainty is how steeply the birth rate fell during the famine years and whether or not to count averted births as a part of the excess mortality. This problem is sensibly resolved by the presentation of lower-bound and upper-bound estimates of excess deaths between 1846 and 1851. (Actually, Mokyr offers two slightly different versions of these sets of estimates and the discussion here relates to the second version in which the national totals are insignificantly higher.) According to these figures, overall excess mortality in the years 1846–51 amounted to 1,082,000 persons if averted births are not counted, and to 1,498,000 if they are. To count averted births among the casualties of the great famine is a thoroughly defensible procedure, though some might not wish to go so far.4

EPIDEMICS OF DISEASE

Of the more than one million who died, by far the greater number perished from disease rather than from sheer starvation. This was not so much because starvation was not rampant as because one or another of the many famine-related diseases killed them before prolonged nutrition deficiency did. In the absence of sufficient replacement foods, starvation on a massive scale became inevitable when the loss of the potato deprived the people of Ireland of the prolific root which before 1845 had provided an estimated 60 per cent of the national food supply.5 Even though food imports belatedly swelled beginning in the spring and summer of 1847, there remained a significant gap between food needs and available resources throughout the famine years, and besides the overall gap there were serious problems in ensuring that the food in the country reached those deprived of it. Recent research by Peter Solar has highlighted both the enormous food shortfall created by repeated epidemics of potato blight and the relative narrowness of the overall gap owing mostly to the major contribution to supply made eventually by food imports. According to Solar’s elaborate and painstaking calculations, total food consumption in the years 1846–50 was only about 12 per cent less than in the period 1840–5.6 This fact only reinforces the points made earlier about the catastrophically uneven distribution of the overall supply and the far greater importance of epidemic disease in producing unprecedented mass mortality.

The initially enormous food gap in the autumn of 1846 and the following winter (when the government refused to stop grain exports) gave epidemic diseases the opportunity to commence their ravages. It was during 1847 that the scourges of ‘famine fever’ and dysentery and diarrhoea wreaked their greatest havoc, as indicated by official statistics – part of three volumes of data on disease and death collected in conjunction with the 1851 census. These scourges persisted at extremely high levels through 1850. Only in 1851 did their incidence fall to about the rates of 1846.7 Moreover, the great killing diseases were joined in the late 1840s by a series of lesser ones which collectively took a tremendous additional toll. Piled on top of the multitude of infectious and nutrition-deficiency diseases of the famine years was a ferocious epidemic of ‘Asiatic cholera’ in 1849. ‘To the beleaguered Irish’, as the medical historian Laurence Geary has aptly said, ‘it must have seemed as if the hand of providence were raised against them.’8

As in every famine, the quest for food or the means to buy it uprooted large segments of the population and sent them streaming to places where they hoped to find what they so critically lacked. Vagrancy and mendicancy, already prominent features of Irish life before the famine, soared to record heights, and large crowds from the countryside congregated in cities and towns, where they besieged the sellers of provisions, the houses of the well-to-do, the gates of the workhouses, and the doors of food depots and soup kitchens. Similar crowds thronged the public works in the last quarter of 1846 and the first quarter of 1847. These were exactly the disrupted social conditions which promoted the spread of ‘famine fever’. There were actually two distinct types of fever that acted as grim reapers during the late 1840s – typhus and relapsing fever. Among the elements that these different epidemic diseases had in common was the same vector: the human body louse. The micro-organisms which are at the root of typhus fever, and which lice transmit, invade the body through skin lesions, at the eyes, and by inhalation. Relapsing fever usually gains entry by a similar process through scratches on the skin.9 Lice ‘feasted on the unwashed and susceptible skin of the hungry, multiplied in their filthy and tattered clothing, and went forth, carried the length and breadth of the country by a population who had taken to the roads, vagrants and beggars, as well as the evicted and those who had abandoned their homes voluntarily’ in the search for relief from their afflictions.10 Typhus fever was an age-old scourge among the poor in Ireland, especially in times of food scarcity, and as a result there was some natural immunity among them against this disease. The mortality rate from typhus was therefore greater among the better-off segments of the population, whereas relapsing fever made by far its heaviest inroads among the destitute.11

Next to typhus and relapsing fever, the worst killers during the great famine were dysentery and diarrhoea, infectious diseases which were the most widespread and lethal complications of their even more murderous cousins. Attacks of fever had the effects of increasing susceptibility to other infections, including bacillary dysentery, and of raising the risks of mortality when one of these other infections took hold after the body’s resistance had been lowered by the ravages of fever. Again, the radical disruption of normal social life by the famine, and especially the insanitary and crowded conditions found in or around workhouses, fever hospitals, gaols, relief centres, and emigrant ports, facilitated the dissemination of these diseases. The bacillus responsible for dysentery is spread by direct contact with an infected sufferer, through water polluted with the faeces of other victims, and by flies carrying the bacillus.12 The acute dietary deficiencies associated with the famine also inflated the death toll from dysentery and diarrhoea. Starving people will eat almost anything in their urge to assuage the sharp pangs of hunger. The green-smeared mouths of some of the famine dead indicated that they had been reduced to eating grass in their extremity. The famished eagerly sought ‘many curious substitutes for the potato’ – the leaves and barks of certain trees, the roots of fern and dandelion, the leaves of the dock and the sorrel, the berries of the mountains and the bogs, the nettles found in particular luxuriance in graveyards, the pickings of the seashore.13 Though some nourishment was often found in these acts of desperation, in many cases the strange, inedible, or uncooked nature of what was ingested left victims with agonising bowel complaints or fatally aggravated pre-existing dysentery and diarrhoea. In a special category of this kind was ‘Peel’s brimstone’ – the Indian corn so widely used as a substitute for the failed potato, and so much of which at first was poorly ground, poorly cooked (sometimes not cooked at all), or even unmerchantable altogether.14 Discharges of infected faeces, of course, frequently led to the intensification of dysentery and diarrhoea epidemics.

Among the lesser killing infections of the famine were measles, scarlatina, consumption, and smallpox. Mortality from measles increased nearly threefold between 1845 and 1849, while scarlatina deaths were more than twice as high by 1850 than in 1845. Claiming even more lives than either of these diseases in the late 1840s was consumption, the most common form of which was tuberculosis of the lung. Deaths from consumption more than doubled between 1846 and 1847 and remained extremely high in 1848 and 1849. For the three years 1847–9 mortality from consumption and measles closely paralleled one another, with each accounting for about 20,000 officially recorded deaths annually. Measles and scarlatina, as childhood diseases, carried off the very young in great numbers; measles could be especially devastating and was known in some cases ‘to wipe out the children of entire villages within days’. Consumption, on the other hand, was worst among adolescents and young adults. More than a third of all consumption deaths in the decade 1841–51 consisted of people between the ages of ten and twenty-five. As with fever, so too with measles, scarlatina, and consumption: attacks of these infections opened their victims to other diseases and raised the likelihood that they would be fatal.15

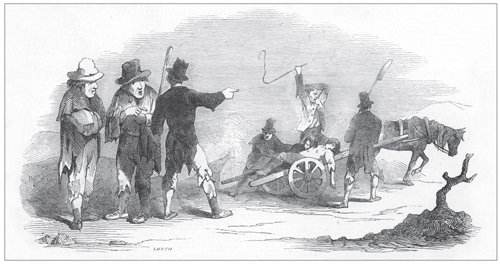

How different were most famine funerals! In the workhouses deaths were so numerous that the authorities resorted to coffins with hinged bottoms so that they could be reused after the bodies had been dumped in mass graves or pits. This sketch of January 1847 depicts a funeral near Skibbereen, Co. Cork, a district just then becoming notorious throughout the United Kingdom for its unspeakable horrors. To be buried in this way, without the presence of family, friends, or neighbours, and without the traditional wake and funeral, was perceived as one of the grossest indignities of the famine. (Illustrated London News)

Most often lethal were two other diseases less closely linked to famine conditions but very much part of this dismal catalogue of destructive epidemics. The first was smallpox, an acute viral disease which seemed largely oblivious of class distinctions, affecting the wealthy as well as the destitute. The mortality rate from smallpox had tripled by 1849 in comparison with the immediate pre-famine years, and the disease was especially virulent in the western coastal counties from Cork to Mayo as well as in Dublin and its rural environs. Those who survived smallpox were invariably disfigured with pock marks on their faces for life, but they were fortunate to be alive at all, as this disease usually killed its victims quickly. Dreaded even more for the same reason was ‘Asiatic’ cholera, the last of the scourges of the famine era. Its appearance in Ireland (first in Belfast) at the end of 1848 was essentially unrelated to food scarcity or the prevailing syndrome of other infectious diseases. But cholera cut a wide swathe of death across much of the country, terrifying all segments of Irish society by the quickness with which it extinguished life (three or four days was usual, and sometimes death occurred within hours) and by its tendency to bypass class boundaries. Before cholera finally subsided in the summer of 1850, after about twenty months of carnage, the authorities had officially recorded nearly 46,000 cases of the disease, and 42 per cent of them – probably an underestimate – were listed as fatal.16

THE GEOGRAPHY OF EXCESS MORTALITY

How were the excess deaths distributed geographically? Excluding averted births, the provincial breakdown is as follows: Connacht accounted for 40.4 per cent of the total, Munster for 30.3 per cent, Ulster for 20.7 per cent, and Leinster for 8.6 per cent. With even relatively prosperous Leinster and Ulster recording 93,000 and 224,000 excess deaths respectively, it could be argued that although its geographical incidence was heavily skewed towards Connacht and Munster, the famine still had the dimensions of a national disaster. It is useful and instructive to disaggregate the provincial statistics since these mask significant intraprovincial variations. Mokyr’s lower-bound estimates of excess mortality by county are set out in Table 6.17

Table 6 |

||||

Average annual rates of excess mortality by county, 1846–51 (per thousand) |

||||

County |

Rate |

County |

Rate |

|

Mayo |

58.4 |

King’s |

18.0 |

|

Sligo |

52.1 |

Meath |

15.8 |

|

Roscommon |

49.5 |

Armagh |

15.3 |

|

Galway |

46.1 |

Tyrone |

15.2 |

|

Leitrim |

42.9 |

Antrim |

15.0 |

|

Cavan |

42.7 |

Kilkenny |

12.5 |

|

Cork |

32.0 |

Wicklow |

10.8 |

|

Clare |

31.5 |

Donegal |

10.7 |

|

Fermanagh |

29.2 |

Limerick |

10.0 |

|

Monaghan |

28.6 |

Louth |

8.2 |

|

Tipperary |

23.8 |

Kildare |

7.3 |

|

Kerry |

22.4 |

Down |

6.7 |

|

Queen’s |

21.6 |

Londonderry |

5.7 |

|

Waterford |

20.8 |

Carlow |

2.7 |

|

Longford |

20.2 |

Wexford |

1.7 |

|

Westmeath |

20.0 |

Dublin |

–2.1 |

|

|

||||

Even within Connacht the difference between Mayo and Leitrim was substantial, though the most noteworthy fact is that all five counties in that province registered higher rates of excess deaths than any county elsewhere in Ireland. In a second group of counties covering most of Munster and the southern portion of Ulster, excess mortality was also fearfully high. On the other hand, the rate of excess deaths was comparatively moderate in mid-Ulster (Tyrone and Armagh) and in west Leinster, while a low rate was characteristic of east Leinster and the northern portion of Ulster. Given what is known of their social structures, it is somewhat surprising that Limerick in the south-west and Donegal in the north-west escaped the brutal rates of excess mortality suffered by the rest of the west of Ireland.

In seeking to explain these wide geographical variations, Mokyr used regression analysis to test the potency of an assortment of independent variables. The results of the regressions indicate that neither the pre-famine acreage of potatoes nor rent per capita was related to the differing geographical incidence of the famine. The factors that correlate most strongly with excess mortality are income per capita and the literacy rate. The counties with the lowest incomes per capita and the highest rates of illiteracy were also the counties with the greatest excess mortality, and vice versa. In addition, the proportion of farms above and below 20 acres correlates positively with excess death rates. As the proportion below 20 acres increases, the excess mortality becomes progressively worse, and as the proportion above 20 acres rises, the excess deaths progressively fall. The grim reality was that poverty, whether measured by dependence on wage labour or by reliance on inadequate landholdings, greatly increased vulnerability to the mortality of the famine. This was true even in regions of the country usually regarded as relatively prosperous. Sheer location offered little protection to labourers and smallholders cursed with inadequate personal resources. Ultimately, the successive failures of the potato claimed as many victims as it did in Ireland because so high a proportion of the population had come to live in a degree of poverty that exposed them fully to a horrendous accident of nature from which it was difficult to escape.18

EMIGRATION MEASURED AND DISSECTED

Emigration, of course, did offer the chance of escape, and that chance was seized by no fewer than 2.1 million Irish adults and children between 1845 and 1855. Of this horde, ‘almost 1.5 million sailed to the United States; another 340,000 embarked for British North America; 200,000–300,000 settled permanently in Great Britain; and several thousand more went to Australia and elsewhere’. As Kerby Miller has observed in his monumental study of 1985, ‘more people left Ireland in just eleven years than during the preceding two and one-half centuries’.19 A significant portion of those who departed in these eleven years would undoubtedly have left even if there had been no famine, for the emigrant stream had been swelling in the decade immediately before 1845. As many as 351,000 had sailed from Ireland to North America alone between 1838 and 1844 – an average of slightly more than 50,000 a year, as compared with an annual average of about 40,000 from 1828 to 1837. If the rate of increase recorded between these two periods had simply been maintained in the years 1845–51, then 437,500 people would probably have journeyed to North America anyway. But the actual number of Irish emigrants who went overseas in those years amounted to more than a million. Departures during the immediate aftermath of the famine were almost as enormous as during the famine years themselves. Of the total of 2.1 million who left between 1845 and 1855, 1.2 million fled before 1851 but as many as 900,000 departed over the next five years.20

THE ‘COFFIN SHIPS’

The mass emigration of the famine era has been associated ever since in the popular mind with the horrors of the ‘coffin ships’ and Grosse Île. And no serious account of the enormous exodus of those years can overlook these tragic events, their causes, and the deep imprint that they have left on the public memory of the famine. It should be stressed, however, that this disastrous episode was confined to 1847. The panic quality of so much of the emigration in that year meant, among other things, that many of the emigrants were already sick or infected with disease when they embarked, that both the cross-channel steamers and the transatlantic ships were more than usually overcrowded, and that passengers had often made too little preparation for the long journey of six or even seven weeks. Those who arrived in Liverpool in a healthy condition frequently went down with disease when they had to seek temporary shelter in the overcrowded, insanitary, and foul-smelling lodging-houses and cellars of that city while awaiting passage to the new world. Liverpool was so overwhelmed by the Irish inundation of 1847, and so ravaged by epidemics of disease, that thousands of would-be emigrants either perished there or were deprived of the financial means to go overseas.21 The panic quality of the exodus of 1847 also swept up a disproportionate number of the poorer members of Irish society (with a greater susceptibility to disease), and Canada was therefore the destination of an unusually high proportion of the emigrants of that year (about 45 per cent), for the simple reason that steerage fares to British North America might be as little as half of those on the now heavily trafficked routes to United States ports. But there was a steep price to be paid for cheapness. At this stage the passage to Canada was very loosely regulated, with the greatest overcrowding and the least adequate provision for food, water, sanitation, and medical facilities. The traffic also took place characteristically in the ‘timber ships’ whose normal load on the journey over to Europe consisted of the products of the great Canadian forests. Not only were such ships unsuitable in various ways for heavy passenger traffic on the return journey, but many of them were also in poor seafaring condition.22

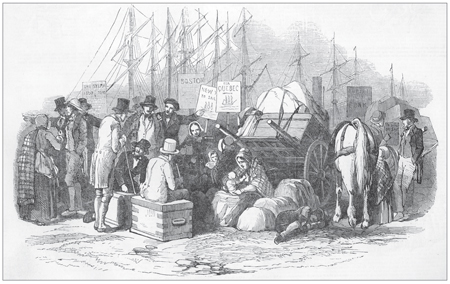

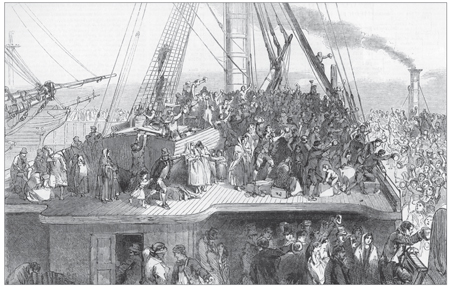

By the spring of 1851, when this sketch of emigrants on the quay at Cork first appeared, the enormous wave of famine emigration was cresting. In that year alone, almost 250,000 persons departed the country. Altogether, between 1845 and 1855 some 2.1 million people – an astounding number – left Ireland, with 1.5 million sailing to the United States. In the earliest years of the famine a high proportion of all Irish emigrants (45 per cent in 1847) went to Canada, and many did so under appalling conditions at sea and upon landing at Grosse Île. But the horrors of the ‘coffin ships’ of 1847 did not persist, and emigration to Canada slackened to only 10 or 15 per cent of the total after 1848. Like their counterparts elsewhere, these Cork emigrants of 1851 faced a long journey – the Atlantic crossing then lasted about six weeks. (Illustrated London News)

The suffering associated with the ‘coffin ships’ need not only be imagined, for the Limerick landlord, philanthropist, and social reformer Stephen de Vere penned a vivid account after travelling as a steerage passenger to Canada in the late spring of 1847:

Before the emigrant is a week at sea, he is an altered man. . . . How can it be otherwise? Hundreds of poor people, men, women, and children, of all ages, from the drivelling idiot of ninety to the babe just born; huddled together without light, without air, wallowing in filth and breathing a fetid atmosphere, sick in body, dispirited in heart . . . ; the fevered patients lying between the sound in sleeping places so narrow as almost to deny them the power of indulging, by a change of position, the natural restlessness of the diseased; by their agonised ravings disturbing those around them and predisposing them, through the effects of the imagination, to imbibe the contagion; living without food or medicine except as administered by the hand of casual charity; dying without the voice of spiritual consolation, and buried in the deep without the rites of the church.23

De Vere assured civil servants at the Colonial Office in London that the conditions on this particular ship, though wretched enough, were actually ‘more comfortable than many’.24 In retrospect, the multiple elements that contributed to the catastrophe at Grosse Île and further afield can be clearly delineated.

Already by the end of May 1847 there were forty vessels in the vicinity of Grosse Île, with as many as 13,000 emigrants under quarantine, stretching in an unbroken line two miles down the St Lawrence. Another report only a week later put the number of refugees on the island at 21,000.25 The situation remained beyond control for months. Even in early September, with the shipping season drawing to an end, no fewer than 14,000 emigrants were still aboard ships in the river and being held in quarantine.26 The death toll at sea had been extremely high on many of these ships, and disease of course continued its ravages as the surviving passengers were prevented from coming ashore for long periods. The dead lay among the living – or the barely alive – for days without removal or burial, and it was only with difficulty that bodies could be cleared from the holds. The quarantine authorities at Grosse Île were limited in what they could do to speed the release of such a horde of refugees, even when they recognised that keeping them on the ships was a death sentence from contagion. Frenzied efforts were made to expand the hospital and other medical facilities on the island, but as late as August accommodation still fell far short of needs. At that point the hospital sheds and tents could cater for about 2,000 sick and 300 convalescents, along with another 3,500 regarded as healthy but not yet qualified for release.27

Under these appalling conditions the death toll was extraordinary. Shortly after the arrival of the first ship, deaths numbered 50 a day, and as many as 150 people were buried on 5 June. The monument that was eventually erected over the mass grave at Grosse Île – located at the western end of the island and covering six acres – proclaims that 5,424 persons lie entombed there. This huge burial-ground is the largest of the mass graves of the great famine, in or out of Ireland. But the more than 5,000 dead lying there are only a fraction of those thought to have died on the coffin ships at Grosse Île, on the island itself, or elsewhere in Canada soon after their arrival. One careful recent scholar has estimated that a minimum of 20,000 persons perished on the island or on the ships around it, and he has emphasised that ‘this number does not include the thousands of others who, having survived Grosse Île, reached Quebec city, Montreal, Kingston, Toronto, and Hamilton, only to die there in fever hospitals and emigrant sheds’.28 Another expert, Kerby Miller, has calculated that the death toll among the almost 100,000 emigrants to British North America in 1847 reached at least 30 per cent of the total. To this minimum of 30,000 deaths on the Canadian route or in Canada itself are to be added another 10,500 people who perished on their way to the United States or shortly after arriving there in the same year (about 9 per cent of the total of more than 117,000).29 In short, the combined mortality associated with the phenomenon of the ‘coffin ships’ was not far short of 50,000 persons.

But the tragic story of the ‘coffin ships’ and the appalling scenes at Grosse Île in 1847 must not be allowed to obscure the larger reality that the vast majority of the two million Irish emigrants of the period 1845–55 survived their arduous journey and began to carve out new lives for themselves in the United States, Canada, and Australia. From what social groups were the emigrants of these years drawn? We are better informed about the emigrants of the early 1850s than about those of the late 1840s. It would appear that in the years 1851–5 between 80 and 90 per cent of all Irish emigrants consisted of common or farm labourers and servants. Skilled workers never constituted more than 11 per cent of the total in the early 1850s (the unweighted average was about 9 per cent), and farmers never accounted for more than 8 per cent (the unweighted average in their case was less than 5 per cent). In the late 1840s the lower-class composition of emigrants was less pronounced but not markedly so. According to manifests of vessels sailing to New York City in 1846, three-quarters of the Irish passengers were either labourers or servants; artisans made up 12 per cent and farmers only 9.5 per cent of the remainder.30 Admittedly, it was notorious that Irish emigrants disembarking at United States ports were much superior in condition to those arriving in British North America. But the exodus to Canada, though favoured by the poorest because of the lower fares, was also much smaller in scale and could not have changed the picture greatly. The conclusion is inescapable that in both the late 1840s and early 1850s the overwhelming majority of emigrants were drawn from the lowest classes of Irish society. Compared with pre-famine emigrants, they were less likely to be skilled or to have been farmers. And as Kerby Miller has emphasised, they were more likely to be Catholic, Irish-speaking, and illiterate.31

From which parts of Ireland was the exodus heaviest? Three areas stand out as having experienced high or very high rates of emigration: south Ulster, north Connacht, and much of the Leinster midlands. The same areas had been notable for a heavy stream of departures in the years 1815–45, and thus the famine period saw the continuation of the pre-famine trends in this respect. As Cousens showed, the prominence of these regions in the pre-famine exodus was mostly the result of the contraction and virtual collapse of the domestic textile industry, especially the home spinning and weaving of linens, under the withering impact of the industrial revolution in Britain and the north-eastern corner of Ireland. Although the decline of cottage industry was already far advanced by the late 1830s, with hand spinning having become altogether obsolete, the ruin of the handloom weavers was delayed until the 1840s, when many of them joined the famine exodus.32

But high rates of emigration during the famine years were usually the result of a combination of factors. According to Cousens, the extensive movement from Leitrim and Roscommon as well as from Longford and Queen’s County was mainly owing to the coincidence of a heavy preponderance of small holdings with high rates of eviction. In addition, the pressure of heavy poor rates was a factor of considerable importance in promoting emigration from Cavan, Monaghan, Leitrim, and Longford, where not only were the rates high but a relatively large proportion of the ratepayers also occupied holdings valued at £4 to £5, or just above the threshold of liability to rates.

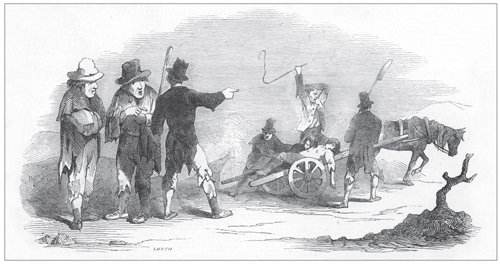

These two sketches of July 1850 show emigrants departing from Liverpool for America. Many intending Irish emigrants never got beyond Liverpool. In the first surge of departures in 1847, many of the fleeing were already infected with fever and died or suffered long agonies in Liverpool, which was overwhelmed by the Irish inundation in that year. Even if they arrived at Liverpool in sound health, Irish emigrants initially ran a high risk of contracting disease in the noisome lodging-houses and stinking cellars of the city. Long delays in departure owing to disease could strip would-be emigrants of their passage money. But by the early 1850s the Liverpool authorities had brought the health crisis well under control. (Illustrated London News)

On the other hand, relatively low emigration was characteristic of most of Ulster, the south-west, and the south-east. Flight was reduced in most of the northern counties by the moderate level of destitution, the correspondingly low poor rates, the scarcity of evictions, landlord paternalism, and the availability of internal migration and factory employment as alternatives to emigration. By contrast, the high levels of destitution that prevailed throughout most of the south and in the far west operated to restrict departures among smallholders, agricultural labourers, and farm servants. Even though labourers and farm servants constituted the most numerous category of emigrants during the famine, they were also the groups who least possessed the resources needed to depart. This difficulty seems to have been most acute in the Munster counties, four of which (Clare, Cork, Kerry, and Tipperary) actually experienced an increase in the ratio of farm workers to farmers between 1841 and 1851. In Waterford there was a substantial decline, but the ratio there was still higher in 1851 than in any other Irish county (Dublin excepted), and not surprisingly, Waterford’s rate of emigration was one of the lowest in the country.33

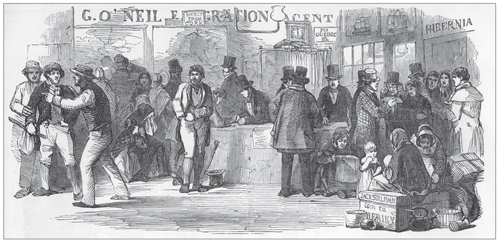

Departing emigrants usually arranged the details of their sea journeys at the office of an emigration agent, as depicted in this sketch of 1851. Fares were probably somewhat higher by the early 1850s than before 1845. Even the cheapest steerage passage to New York at the end of the famine period was usually at least 75s., or not far short of £20 for a family of five. Perhaps only about 5 per cent of all emigration during the famine was assisted, since neither the landlords nor the government gave much aid. Many emigrating farmers paid for their passage from sales of their crops and livestock, but an increasing proportion of emigrants in the early 1850s benefited from the flood of remittances sent home by relatives who had left earlier. (Illustrated London News)

Destitution, however, did not always act as a sharp brake on emigration. In fact, four of the five counties with the highest rates of excess mortality during the famine years (Leitrim, Mayo, Roscommon, and Sligo) also ranked among the counties with the heaviest rates of emigration. Perhaps the likeliest explanation for this apparent anomaly is that north Connacht, as noted earlier, had been a centre of emigration before 1845, and that remittances from previous emigrants relieved their relatives and friends who now followed them from having to depend exclusively or largely on their own resources. In south Ulster as well, emigration was not checked by destitution. The exodus from Cavan, Monaghan, and Fermanagh was extraordinarily heavy, even though in all three counties the rate of excess mortality was considerably above the average. This region too had been remarkable as a centre of emigration in the pre-famine years, and presumably remittances again allowed many of its poor to escape abroad.

Apart from south Ulster and north Connacht, however, the relationship between emigration and excess mortality was usually inverse, as Kerby Miller has observed. This pattern was perhaps clearest in the mid-west and the south-west. In Galway, Clare, and west Cork, where excess deaths were high, emigration was relatively low. Conversely, in Donegal and Limerick, where excess mortality was quite low, emigration was either very heavy (Donegal) or moderately high (Limerick). An inverse relationship similar to that prevailing in Limerick and Donegal was also strikingly evident among certain of the Leinster counties. Carlow, for example, ranked very low in the scale of excess deaths but very high in the scale of emigration, and the same was true of Kildare, Kilkenny, and especially Louth. To be sure, the inverse relationship was often less pronounced, but it was rare for a low level of excess mortality to be associated with anything less than a moderate level of emigration. Even Wexford and Dublin, which ranked lowest in the excess mortality scale, experienced moderate rates of emigration.34

Even though emigration was already a normal occurrence in certain regions of the country before 1845, its acceptability increased enormously throughout most of Ireland in the late 1840s and early 1850s. The exodus of the late 1840s, and especially that of 1847, was characterised by an often panic-driven desperation to escape that swept aside the prudential considerations and customary restraints of former years. Neither reports of adverse conditions abroad, nor lack of adequate sea stores and landing money, nor the absence of safe vessels could check the lemming-like march to the ports. Most of those who left embraced emigration as their best – or their only – means of survival, even if it entailed, as it did for thousands, the perilous crossing of the North Atlantic in the middle of winter.35 Inevitably, departures under such conditions produced disasters at sea or upon landing, as on the ‘coffin ships’ and at Grosse Île in 1847. Fortunately, the vast majority of emigrants escaped such depths of suffering. In 1848 the death rate among passengers to Canada fell to barely more than one per cent, and voyages to the United States throughout the famine years were much less dangerous to the health and safety of Irish emigrants, largely because of stricter regulation of passenger ships.36

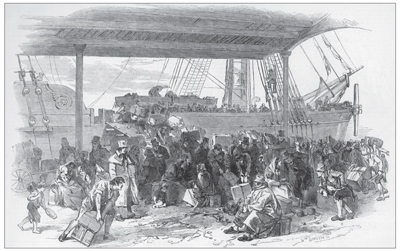

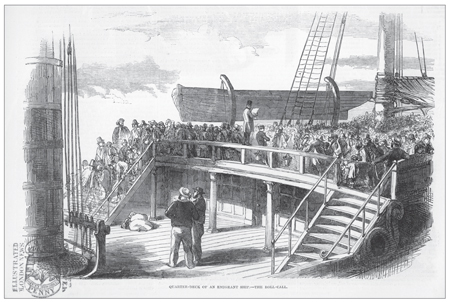

The practice of calling the roll on the quarter-deck of an emigrant ship, depicted in this illustration of July 1850, may be taken to signify some tightening in the regulation and management of ships carrying transatlantic passengers after the horrors of 1847. But throughout the late 1840s and early 1850s there was considerable variability in the quality of the ships involved in the trade, and conditions below decks were far from satisfactory. American ships were much preferred to British because they were generally less crowded and had the advantage in design, accommodation, and speed. But whether the ships were American or British, emigrants invariably suffered from overcrowding in steerage, fetid quarters, poor food and sanitation, and a seemingly endless journey. (Illustrated London News)

At first, the mass exodus aroused little hostile comment in Ireland. Landlords who encouraged departures were not initially condemned, provided that they gave some modest assistance towards the emigration of their tenants; instead, such landlords were frequently praised for their generosity. For a time after 1845 Catholic priests generally accepted and often even promoted emigration, and nationalist newspapers and politicians usually acquiesced in it. But by late 1847 and early 1848 the whole tone of public discussion on the subject had changed drastically. Priests, editors of popular newspapers, and nationalist politicians of all factions were joining in a loud chorus of denunciation, stigmatising emigration as forced exile. This radical shift in opinion coincided with, and was largely prompted by, the bitter realisation that the British government had laid aside any conception of the famine as an imperial responsibility and had terminated all major schemes of direct relief funded by the treasury. The hypercriticism of emigration evident among clerics and nationalists by 1848 did nothing to stem departures. But along with other factors, it helped to undermine earlier popular conceptions of the famine as divine punishment for sin or as the will of an inscrutable providence.37 Increasingly after 1847, blame for emigration and indeed for the famine itself was laid at Britain’s door, and political events, to be discussed in the next chapter, had much to do with this fundamental and long-lasting development.

Notes

1. L.M. Cullen, An economic history of Ireland since 1660 (London, 1972), p. 132.

2. Vaughan and Fitzpatrick, Irish historical statistics, pp. 5–15.

3. S.H. Cousens, ‘Regional death rates in Ireland during the great famine, from 1846 to 1851’, Population Studies, xiv, no. 1 (July 1960), pp. 55–74.

4. Mokyr, Why Ireland starved, pp. 263–8.

5. Bourke, ‘Visitation of God’, p. 52.

6. Solar, ‘No ordinary subsistence crisis’, p. 123.

7. Kennedy et al., Mapping, p. 105.

8. L.M. Geary, ‘What people died of during the famine’ in Ó Gráda, Famine 150, p. 101.

9. Ibid., p. 102.

10. Ibid., pp. 103–4.

11. L.M. Geary, ‘ Famine, fever, and the bloody flux’ in Póirtéir, Great Irish famine, p. 83.

12. Geary, ‘What people died of’, p. 106.

13. McHugh, ‘Famine in Irish oral tradition’, pp. 399–400.

14. Geary, ‘Famine’, pp. 84–5; McHugh, ‘Famine in Irish oral tradition’, pp. 407–9.

15. Kennedy et al., Mapping, pp. 112–16.

16. Geary, ‘What people died of’, pp. 107–8; Kennedy et al., Mapping, pp. 121–4.

17. Mokyr, Why Ireland starved, p. 267.

18. Ibid., pp. 268–75.

19. Miller, Emigrants and exiles, p. 291.

20. Ibid., pp. 199, 569.

21. For the Irish inundation of Liverpool in 1847 and its effects, see Neal, ‘Lancashire’, pp. 26–48; idem, Black ’47, passim. Pauper burials, mostly of Catholics, increased by almost 5,000 in Liverpool in 1847, and Ó Gráda concludes that ‘some tens of thousands of famine refugees perished’ in Britain as a whole during the late 1840s. See Ó Gráda, Black ’47 and beyond, pp. 111–13.

22. Miller, Emigrants and exiles, p. 292; Quigley, ‘Grosse Île’, pp. 20–40.

23. Quoted in Brendan Ó Cathaoir, Famine diary (Dublin and Portland, Oregon, 1999), p. 120. See also Woodham-Smith, Great hunger, p. 226; Quigley, ‘Grosse Île’, pp. 25–6.

24. Quoted in Quigley, ‘Grosse Île’, p. 25.

25. Ó Cathaoir, Famine diary, pp. 120–1; Quigley, ‘Grosse Île’, pp. 24, 27.

26. Quigley, ‘Grosse Île’ in Crawford, Hungry stream, p. 32.

27. Ibid., p. 31.

28. Ibid., p. 36.

29. Miller, Emigrants and exiles, p. 292.

30. Ibid., pp. 295, 582. The low percentages of farmers among the emigrants of both the late 1840s and the early 1850s are undoubtedly a reflection of the youthfulness of a large proportion of those who went overseas. Many of those recorded as farm labourers and servants were the sons and daughters of farmers.

31. Ibid., pp. 293–8.

32. Cousens, ‘Regional variation in emigration, 1821–41’, pp. 15–30; Miller, Emigrants and exiles, p. 293.

33. David Fitzpatrick, ‘The disappearance of the Irish agricultural labourer, 1841–1912’, Ir. Econ. & Soc. Hist., vii (1980), p. 88.

34. My discussion of variations in the rate of emigration at the county level is based on an elaborate set of statistical calculations made by Joel Mokyr and not published in his book Why Ireland starved. I am deeply grateful to him for placing these data at my disposal.

35. Miller, Emigrants and exiles, pp. 298–300.

36. Mokyr, Why Ireland starved, pp. 267–8.

37. Miller, Emigrants and exiles, pp. 301–7.