It was above all the poverty of such a large segment of the Irish population that made the great famine so destructive of human life. People with the scantiest resources were the most likely to succumb to starvation or disease when the potato crop failed repeatedly in the late 1840s. The dimensions and regional distribution of poverty on the eve of the famine can be gauged in a variety of ways. Contemporaries considered those who were exclusively or heavily dependent on the potato for their food to be poor, and historians today would strongly agree. Such people constantly struggled to keep their heads barely above water and were plunged below it whenever bad weather or crop disease or their own personal misfortunes struck without warning. Nowhere else in Europe did so high a proportion of the population come to rely on the potato for its food. P.M.A. Bourke, who did more than any other recent scholar to enlighten us on the central role of the potato in pre-famine Ireland, estimated that in 1845 as many as 4.7 million people, out of a total of about 8.5 million, depended on this root as the predominant item in their diet. Of these 4.7 million, some 3.3 million had a diet consisting more or less exclusively of potatoes, with milk or buttermilk and fish as the only other important sources of nourishment.1 Dominating the ranks of the potato-eaters – and the poor – were landless agricultural labourers, cottiers (the smallest landholders), and other tenants with less than 20 acres of land. These groups made up that huge portion of the Irish population for whom the potato was either the very staff of life or, even in the northern ‘oatmeal zone’, still the predominant item in their diet. In those years before 1845 when the potato was in usual abundance, the average adult male of the labourer, cottier, or smallholder class consumed 12 to 14 lb of potatoes every day. This prodigious quantity of food, though stodgy and monotonous, generally maintained health when taken in conjunction with sufficient milk, since the milk supplied the nutriments missing in the potato. Though middling and larger farmers also included some potatoes with their more varied diets, their average daily consumption was only about one-half or one-quarter respectively of that of the poorest social groups.2 The poorest together consumed perhaps 75 per cent of all the potatoes eaten by humans in Ireland on the eve of the famine, and they fed their pigs on a large additional fraction of the animal portion of the crop.3 Pre-famine poverty was thus very much a matter of class, and famine mortality would be too.

Pre-famine poverty also exhibited strong regional dimensions, which can be seen in relation to the distinctly inferior quality of rural housing and the prevalence of illiteracy in the countryside. Though some observers maintained that farmers of real substance often disguised their wealth by living in houses of the meaner sort, this claim has been effectively refuted by recent research, and there is every reason to believe that the quality of housing occupied by different segments of the population is a reasonably good proxy for relative income and its regional distribution. The commissioners responsible for the 1841 census distinguished four different types of house. Those in the fourth or lowest class were ‘all mud cabins having only one room’, while those in the third class were ‘a better description of cottage, still built of mud, but varying from 2 to 4 rooms and windows’. In Ireland as a whole, more than three-quarters of all houses fell into one or the other of these two lowest categories, and nearly two-fifths consisted of one-room mud cabins. The south-western and western counties from Cork to Donegal had the highest concentrations of fourth-class housing. In virtually every barony west of a line drawn from Derry to Cork, at least 40 per cent of the houses were in this category, and in some western baronies the proportion exceeded 60 per cent. By contrast, counties in Leinster and Ulster generally had substantially lower concentrations of one-room mud cabins and higher proportions of better houses.4 A similar regional pattern emerges from an analysis of the 1841 data on literacy, which has commonly been employed as another proxy for poverty.5 Illiteracy was greatest along the western seaboard on the eve of the famine. Male illiteracy topped 60 per cent in 1841 in Mayo, Sligo, Galway, and Kerry, with Cork, Clare, Roscommon, and Donegal not far behind. Somewhat lower levels of male illiteracy prevailed in an intermediate zone comprising most of Munster and the north midlands, whereas male literacy was highest in the north-east and the south-east as well as in Dublin.6

Confirming this picture of regional variation in the extent of pre-famine poverty is a recently published analysis of data from the mid-1830s on the daily wages and annual income of male labourers. Landless agricultural labourers constituted a substantial fraction of the population on the eve of the great famine. Together with their dependants, they numbered nearly 2.3 million in 1841, or more than a quarter of the total.7 Many of them were ‘bound’ labourers, contracted to work for a particular farmer for a certain number of days per year in return for a cabin, a small plot of ground, and other ‘privileges’. Other agricultural workers were ‘unbound’ and took work where they could find it, earning a wage that often included their diet or food, but sometimes did not. Underemployment was an especially severe problem among unbound labourers, many of whom had to migrate seasonally to other parts of Ireland or even to Britain in order to eke out a meagre living. Taking these and other complexities into account, the authors of the aforementioned study have enhanced our understanding of pre-famine poverty by mapping the income of Irish male labourers by county in 1835. Their map of the mean daily wage makes it possible to distinguish three broad areas: an eastern seaboard region of relatively high wages, an intermediate area of lower wages extending down through the centre of the country from Donegal to Cork, and a western band of counties (Kerry, Clare, Galway, and Mayo) where daily wages were lowest. Their companion map and analysis of average annual income demonstrates that labourers in the west were the recipients of even lower annual incomes, as compared with their eastern counterparts, than suggested by the map of daily wages alone.8 Indeed, by another calculation the average yearly income of labouring families in Connacht in the mid-1830s was less than three-fifths of that in Leinster, the province with the highest wages.9 These figures are of the utmost significance for the catastrophe that was about to happen. Confronted by the failure of their potatoes in the late 1840s, western labouring families lacked the means to buy food. They ‘stood penniless in the face of doom’.10

POPULATION EXPLOSION

If poverty was widespread in pre-famine Ireland, and if it was especially acute in the west and much of the south, what had made it so, and was the problem actually worsening in the decades immediately before the famine? Pre-famine Ireland was notorious for the rapidity of its population growth, and in the absence of sufficient economic expansion (there was certainly expansion but not enough) the swift pace of demographic increase firmly depressed the general material welfare of at least half the population. The great spurt in the population of Ireland began in the mid-eighteenth century and continued strongly, though with substantial regional variations, until the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815. Only in the immediate aftermath of the wars did there finally occur a definite slackening in the national rate of growth, which persisted until the famine. Even so, the overall magnitude of the increase was enormous. Between 1750 and 1845 the total population of the country mushroomed from about 2.6 million to 8.5 million, or by some 225 per cent in a century.11 Ireland was hardly alone in experiencing rapid population growth in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. What was distinctive about the Irish case were two things: the rate of expansion, which was exceptional even by contemporary European standards (perhaps the fastest of ‘any society in Europe in the century before the famine’),12 and the relative weakness of the accompanying industrialisation. The initial spread of the domestic system of rural industry between 1750 and 1815 was reversed in the three decades before the famine, when much of the Irish countryside was deindustrialised under the impact of the industrial revolution in Britain and around Belfast.13

Historians are not in agreement on the reasons for the Irish population explosion, and there has been much debate about the exact role of the potato in the demographic upsurge. Some historians have assigned to the potato a primary role in initiating and sustaining the spurt, suggesting that it significantly lowered the age of marriage by making it much easier to establish new families on very small plots of often marginal land.14 Other scholars have been inclined to see the growing dominance of the potato in the Irish diet more as a relatively late response (mostly after 1800) to the pressures of an already rapidly expanding population on available resources of land and employment.15 Some fall in the death rate also contributed to the swelling population, though the extent of its contribution is disputed. Improved diet and better transport no doubt helped considerably and make much more comprehensible the almost century-long gap between the last major famine of 1740–1 and the great famine. But about the consequences of the population explosion there is considerably less disagreement. Greatly increased demand for land, especially during the long period of almost continuous warfare in Europe and further afield between the early 1790s and 1815, meant that tenants of all kinds had to pay much higher rents. Even when farm prices tumbled after 1815, landlords were slow to adjust rents, and population growth exerted upward pressure on all land values. This affected adversely not only farmers but also landless agricultural labourers, who were compelled to hire land on a seasonal basis, usually from farmers, in order to grow potatoes. Such was the keenness of the competition for this kind of potato ground (generally called conacre) that it was a leading cause of agrarian violence in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Besides pushing rents higher, the population explosion also helped materially to keep the average income of agricultural and rural textile workers at relatively low levels. Using the voluminous data collected by the poor inquiry commission in the mid-1830s, Joel Mokyr has estimated that the average annual income of Irish labourers and their dependants was only barely more than £13, a figure that includes their income from pigs as well as other sources. Though he places per capita income in Ireland in 1841 slightly higher than this, the figure for Ireland is only a little more than 60 per cent of the corresponding number for Britain.16

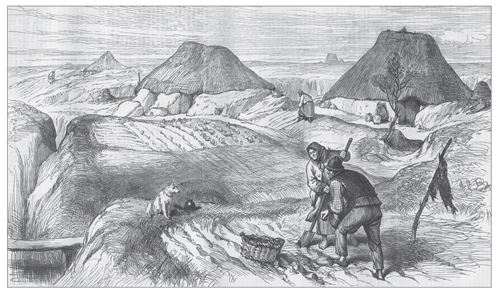

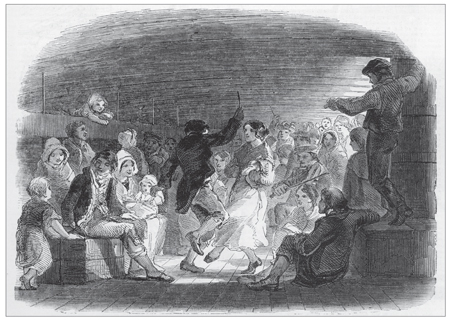

This ‘bog village’ in County Roscommon probably came into existence between 1780 and 1845, when land-hungry tenants invested extraordinary effort in reclaiming bogs, mountainsides, and other waste land. Much of this land was devoted to potato cultivation in ‘lazy beds’, as in this sketch of 1880. Access to waste land initially came cheaply, as landlords charged little or no rent at first in order to promote reclamation on their estates. The combination of an excess supply of labour, cheap and abundant waste land, and the nutritious potato stimulated rapid population growth – from an estimated 4.4 million in 1791 to 8.5 million in 1845. But by the 1840s this style of estate development was out of fashion with most landlords. (Illustrated London News)

The population explosion was also responsible for some of the already observed regional variations in the levels of wages and income, the quality of rural housing, and the degrees of literacy – in other words, for regional differences in poverty. The demographic upsurge was not evenly spread across the island. From the early 1750s to the early 1790s Ulster experienced the fastest demographic growth of the four provinces, a ranking consistent with the lusty development of rural textile industry and rising real wages for linen weavers and other workers in that province during the same period. The slowest growth was in Leinster, with Munster and Connacht occupying an intermediate position. But over the next thirty years (1791–1821) the rankings changed dramatically, with Ulster’s growth being even slower than that of third-place Leinster, and with Connacht and Munster moving into the first and second positions respectively. Ulster’s rate of expansion in this later period was curtailed by relatively heavy emigration and probably ‘the fact that earnings for most weavers in Ulster’s staple industry were no longer rising in real terms after the 1790s’.17 On the other hand, the wartime boom in farm prices brought unprecedented benefits not only to large dairy farmers and graziers but even to smallholders involved in tillage and pig production. It is difficult not to think that the unusually swift pace of population growth in Connacht and Munster in this period was mostly the result of the disproportionate effects of the wartime boom on small farmers and cottiers in these two provinces, though in the case of Connacht the expansion of the domestic system in textiles (especially among women) no doubt also played a role of some significance.18

As already mentioned, the end of the wartime boom initiated a general demographic adjustment in Ireland, with population growth slowing down quite sharply in the decades before the famine. All four provinces were affected by this deceleration in the rate of expansion. But as in the period 1791–1821, so now too in the years 1821–41 Connacht and Munster again headed the provincial list. In other words, population was still growing fastest in those regions – the west and the south-west – with the highest degrees of poverty. One way of interpreting this pattern, as Joel Mokyr indicates, is to say that ‘population grew unrestrained, continuously exacerbating poverty, thus making the resolution of the problem by a catastrophe ultimately inevitable’.19 But the matter is not so simple. As Cormac Ó Gráda has pointed out, the deceleration in the rate of growth seems to have been greater than average in the west and the south-west between 1821 and 1841, and ‘presumably, the adjustment would have continued in that might-have-been Ireland without the potato blight in the late 1840s’.20 But the general economic conditions of the three decades before the famine were not nearly as favourable to cottiers and smallholders as those which had prevailed during the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, and it is difficult to resist the conclusion that the exposure of the poor of the west and south-west in the event of some catastrophe was rising in tandem with increasing population. As Ó Gráda concedes, growth in these regions was still fairly vigorous, even if slower.

TOWARDS THE ABYSS?

Whether Ireland was sliding towards the abyss in the decades before the famine is a question on which historians’ views have shifted considerably over the last twenty or thirty years. Where once the tendency would have been to say that the condition of the great majority was clearly worsening, now the tendency is to say that the general lot of a large minority was improving, and that even the majority were not going downhill fast. It has long been firmly established that, considered as a national unit, the Irish economy was much larger, and Irish society much wealthier (or much less poor), on the eve of the great famine than it had been in 1750 or even in 1815. The decline of hand manufacture in the countryside and in many southern provincial towns after 1800, and even more rapidly after 1825, was counterbalanced by the vigorous growth of textile mills and factories in Belfast and the surrounding Lagan valley. Cotton was very important in this region throughout the first quarter of the nineteenth century, but in the second quarter it was overtaken and then completely eclipsed by the linen industry. By 1850 Belfast and the Lagan valley were well on the way towards seizing industrial leadership in linens among all urban centres of the industry in the United Kingdom.21 But if the rise of Belfast was hard to miss, perhaps even more noticeable were the adverse social consequences of progressive rural deindustrialisation between 1800 and 1845. Machine production in mills and factories hurt hand spinners first and handloom weavers eventually. Technological change of this kind heavily contributed to pre-famine rural impoverishment in certain regions of the country, especially west Ulster, north Leinster, and north Connacht. The counties worst affected were Mayo and Sligo in Connacht, Donegal and Tyrone in Ulster, and Longford and Louth in Leinster.22 Still, it would be misleading to connect this development too closely with suffering during the great famine, since of these six counties, only Mayo and Sligo were to experience very high levels of excess mortality in the late 1840s.23

More important than these industrial developments, however, were the changes working their way through the agricultural economy. Two-thirds of the population lived on the land, according to the 1841 census, and agriculture was by far the most important sector of the economy. Cormac Ó Gráda has estimated that on the eve of the famine the value of Irish agricultural output amounted to about £45 million. Given the impressive increases that had taken place in Irish exports of grain and pigmeat just since 1815, this figure must represent a very substantial increase over the corresponding number thirty years earlier. Admittedly, on the pastoral side after 1815 the weakness of demand in Britain for Irish meat (apart from bacon and ham) and for dairy products meant that output in these sectors was expanding only slowly in the three decades before the famine. But under the British protective umbrella provided by the corn laws, Irish grain production leaped upwards, partly on the strength of expanded acreage but also as a result of very respectable increases in crop yields. By the mid-1830s Ireland provided as much as 80 per cent of British corn imports, in contrast to less than 20 per cent in the mid-1790s.24 Farm prices were not at all buoyant during these decades, and there were several severe price depressions, but to a very considerable extent the lower prices were offset by rapidly rising tillage and pig production. Under almost any set of reasonable assumptions the bulk of middling and large farmers must have been at least mildly prospering if the period is considered as a whole.25

If pre-famine Irish agriculture was not nearly so backward as has often been claimed, it was still far behind the pace of improvement in England. Agriculture in England and large parts of Scotland was the most advanced in the world, and the educated élites on both sides of the Irish Sea were increasingly conscious of the disparities and increasingly anxious to see the gap reduced. At the top of almost every Irish landowner’s list of Irish agrarian problems was the fragmentation of holdings, and this view was also an integral part of the highly negative image of Irish rural society in Britain. Widely canvassed in Britain was the extreme idea of converting ‘the cottier, who is nicknamed a farmer and who starves on a cow’s grass, into a labourer subsisting on competent wages’.26 Under the acute pressure of the population explosion the subdivision of holdings had been carried to extraordinary lengths by the eve of the famine. Aside altogether from the 135,000 holdings of less than 1 acre in 1844, almost half of the other 770,000 holdings did not exceed 10 acres, while another quarter were between 10 and 20 acres. Barely more than a quarter of the total number of holdings above 1 acre exceeded 20 acres.27 As a result, labour productivity in Irish agriculture was very low by British standards. According to Ó Gráda, ‘the most generous comparison suggests that British output per worker [in agriculture] was about double that of the Irish’.28 Élite observers were quite convinced of the potential scope for large economies of scale within Irish agriculture, if only the ‘surplus population’ could somehow be removed, and there was also a growing desire to expand pastoral farming, perhaps encouraged by price trends that favoured pasture over tillage from the 1830s.29

But if labour productivity was low by hard-to-match British standards, output per acre was relatively high and ‘could well have reached British levels on the eve of the famine’.30 A large part of the reason was the potato, always a heavily manured crop, which replaced the need for fallow in preparation for the cultivation of oats, wheat, or barley, the cereals that usually followed it in rotation. The potato also furnished food for livestock and above all for pigs, and their manure, heaped in front of the dwellings of almost every landholder, was soon returned to the soil, along with enormous quantities of seaweed and sea sand in regions within reach of the coasts. Lastly, ‘as a sturdy pioneer for breaking new ground and clearing land, [the potato] was far more suited to Irish conditions than the less vigorous turnip, which needed a well prepared seed-bed’.31 Along with these inherent advantages of the potato in boosting yields went the intense labour associated with the sowing and management of the crop, a by-product of the abundance of the available work-force and the indispensability of the root. One contemporary observer testified to the unflagging energy which cultivators devoted to the potato:

I have never seen any field cultivation in England, except perhaps hops, where more diligence is discovered [than in growing potatoes in Ireland]. Every ounce of manure is carefully husbanded, and every weed is destroyed. The drainage is made complete; and the hoe, or rather the apology for that instrument [the spade], is constantly going.32

This lavish expenditure of labour power paid dividends in the relatively high nutritional levels and comparative health of the Irish population. Research into the height of Irishmen both before and after 1815 indicates that adult Irish males ‘were taller than their English peers and by implication [were] reared on a healthier diet’.33 These findings also point to the general reliability of the potato as a food source in the pre-famine period. There were undoubtedly some episodes of serious deficiency in the potato crop during the three decades before the famine, with the worst ones occurring in the years 1815–17, 1821–2, 1830–1, and 1839–40, but both the extent of these scarcities and the resulting excess mortality were limited and should not be viewed as the harbingers of an approaching doom. Some contemporary observers saw dietary deterioration in the rapidly spreading use of the ‘lumper’ variety of the potato following its introduction from Scotland soon after 1800. Though the lumper was deficient in taste (it was watery) and in keeping quality, the poor especially favoured it because of its suitability in inferior soils, its higher yields, and its general reliability. Until the appearance of phytophthora infestans in 1845 this preference seemed amply justified by results. Recent scientific research has also confirmed that while the lumper is inferior to premium varieties of the potato, it ranks well among modern supermarket varieties.34

Besides benefiting from relatively high nutritional levels, Irish society displayed definite signs of improvement in certain other areas of material welfare in the early nineteenth century. Consumption of tea, sugar, and tobacco was increasing between the end of the Napoleonic wars and the famine, a trend that could indicate at least some improvement in the average standard of living during that period. The limited number of studies of the cost of living between 1815 and 1845 also point emphatically in this direction. Admittedly, these studies indicate that the decline in living costs was concentrated in the years before 1830, with a sharp drop of perhaps as much as 25 to 30 per cent, but stability in subsistence costs apparently characterised the 1830s and early 1840s.35 Also militating against any notion of advancing immiseration before 1845 is the substantial evidence of improvement in rural literacy. School attendance was increasing modestly – according to one calculation, from 5.5 per thousand people in 1824 to 6.1 per thousand in 1841. Illiteracy was falling after 1815 in all four provinces, though the most impressive declines were concentrated in the wealthier provinces of Leinster and Ulster.36

Nevertheless, these signs of an improvement in average living standards almost certainly mask a deterioration in the position of the poor, who constituted at least half of the population on the eve of the famine. Many rural dwellers must have felt the pain of the ‘scissors effect’ of rising money rents and falling money wages between 1815 and 1845.37 Nutrition levels, though still making adult Irishmen taller than their English counterparts, seem to have been dropping, to judge from the narrowing of the gap in this period between Irish and English male height.38 Rural deindustrialisation, as previously noted, was greatly exacerbating the already severe problem of underemployment. Most telling of all perhaps, there were very few educated contemporaries who believed in the years before the famine that the preceding decades had witnessed improvement in the living conditions of the poor. A massive amount of impressionistic evidence was given on precisely this issue to the poor inquiry commission of the mid-1830s, and Joel Mokyr has systematically analysed the usable replies of the 1,590 witnesses from counties throughout Ireland. The rating of the thirty-two counties on a five-point scale from ‘much deteriorated’ to ‘much improved’ allows Mokyr to construct what has been called a ‘subjective impoverishment index’. In only two counties in the whole of Ireland – Wicklow and Wexford – ‘does the index take on a positive value’.39 Altogether, then, it seems reasonable to conclude that though Ireland was certainly not careering towards economic and social disaster in the decades before 1845, about half of the population were victims of some degree of immiseration and stood dangerously exposed to a foreign and devastating plant disease. The fact that the arrival of this fungus could not have been predicted only made matters worse.

HISTORIOGRAPHY

Long after historical writing about pre-famine Ireland had gathered pace in the 1960s and 1970s, writing about the great famine itself lagged badly behind. For decades, in fact, professional historians carried on the important task of revising our understanding of the Irish past without paying much heed to the most cataclysmic event in the modern history of the country. The professionalisation of Irish history in the twentieth century was closely identified with the journal Irish Historical Studies, founded in 1938. Little was heard of the famine in its pages. In the first half-century of its existence, through a hundred issues, this journal carried a scant five articles on topics related to the famine, and the record of Irish Economic and Social History, founded in 1974, was equally barren in this area.40 The scholars who established and supported Irish Historical Studies, and those who followed in their wake, came to be substantially concerned with debunking nationalist interpretations of the Irish past. Rightly for the most part, they busied themselves with correcting those often very simplistic and emotional accounts in which Ireland and the Catholic Irish were portrayed as victims of British imperialism or Protestant sectarianism, or both together. In general, what came to be called ‘revisionism’ had a triumphal march, slaying one dragon of nationalist historiography after another.

Eventually, however, there emerged such a discrepancy between what ‘revisionist’ historians professed and what many Irish people believed that in certain quarters the revisionist enterprise was subjected to ridicule. Some of this ridicule concerned treatment of the great famine and was directed at historians associated with Trinity College, Dublin, viewed by certain non-professional critics as a bastion of revisionism. In December 1984 a notorious and uproariously funny lampoon of revisionism, as allegedly practised by certain Trinity College historians, appeared in the satirical weekly magazine In Dublin. In what purported to be a flattering review of a supposedly new book entitled The famine revisited by one Roger Proctor, the reviewer, whose name is given as Professor Hugh T. Lyons, tells us with a straight face that Proctor has turned the accepted interpretation of the famine on its head:

Proctor produces an array of evidence to show that most of those who died in the famine years were neither small farmers nor cottiers, but were in fact landlords, their families, and their agents.

The details recounted are harrowing. Richard Mortimer, a landlord in east Kerry, kept a diary for the years 1846 to 1847. He records how, after giving away all his family goods to his tenants (whom he assumed to be starving), he watched powerlessly while his aged father, his wife, and seven children died, one by one, of hunger in the dark winter of 1847. What makes the Mortimer case particularly shocking is that it now emerges from a study of the London money market accounts that two of the Mortimer tenants, Tadhg O’Sullivan and Páidín Ferriter, actually invested considerable sums of money in London in those very years.41

But since such jibes generally came from beyond the redoubts of Irish historians, they could be largely ignored as uninformed or misguided or both.

BRADSHAW’S ATTACK ON REVISIONISM

It proved much harder to ignore the far more serious challenge mounted to the whole revisionist enterprise by Brendan Bradshaw, a formidable and respected historian of early modern Ireland who, though born and bred in Ireland, had made his career in the University of Cambridge in England. In November 1989 Bradshaw published a now famous ‘anti-revisionist’ article in Irish Historical Studies, of all places. In this article, entitled ‘Nationalism and historical scholarship in modern Ireland’, he took the whole revisionist school to task for its pursuit of a kind of scientific, objective, value-free examination of the Irish past. In this approach, Bradshaw charged, the revisionists had employed a variety of interpretive strategies in order to filter out the trauma in the really catastrophic episodes of Irish history, such as the English conquest of the sixteenth century, the great rebellion of the 1640s, and the great famine itself.42 In fact, the famine provided Bradshaw with the best evidence for his case, revealing what he considered ‘perhaps more tellingly than any other episode of Irish history the inability of practitioners of value-free history to cope with the catastrophic dimensions of the Irish past’. In the fifty years since the emergence of their school of history in the mid-1930s, he asserted, they had managed to produce ‘only one academic study of the famine’, and when the revisionist Mary Daly published a brief but significant account in 1986, she too, according to Bradshaw, sought to distance herself and her readers ‘from the stark reality’. Seconding criticisms of Daly’s book made by Cormac Ó Gráda, Bradshaw asserted that she did this ‘by assuming an austerely clinical tone, and by resorting to sociological euphemism and cliometric excursi, thus cerebralising and thereby de-sensitising the trauma’.43

Bradshaw’s views aroused heated controversy, even ad hominem attacks, and spawned a lively and generally useful debate among scholars and a wider audience.44 The echoes of the early clashes can still be heard. It seemed to me at the time, in the early 1990s, as it still does now, that Bradshaw was largely correct in his insistence that professional historians of Ireland had often failed to confront squarely and honestly what he termed ‘the catastrophic dimensions of the Irish past’. His criticisms appeared to be especially relevant to the general scholarly approach to the great famine. That approach had long been almost entirely dismissive of the traditional nationalist interpretation, which laid responsibility for mass death and mass emigration at the door of the British government, accusing it of what amounted to genocide. The problem can be highlighted by considering briefly what were, until the mid-1990s, the only two major book-length studies of the famine – studies which differed markedly in character, interpretation, and audience.

For revisionists, the publication in 1962 of The great hunger: Ireland, 1845–1849 by Cecil Woodham-Smith was not an altogether welcome event.45 These academic historians no doubt envied the commercial success of the book. The great hunger was immediately a bestseller on two continents, and its premier status as the most widely read Irish history book of all time has only grown with the years. But far more troubling to the revisionists was the ‘ungoverned passion’ to which numerous reviewers of the book succumbed. Vigorously protesting against ‘this torrent of muddled thinking’, the late and great historian F.S.L. Lyons called attention in Irish Historical Studies to a striking aspect of the popular response:

Ugly words were used in many reviews – ‘race murder’ and ‘genocide’, for example – to describe the British government’s attitude to the Irish peasantry at the time of the famine, and Sir Charles Trevelyan’s handling of the situation was compared by some excited writers to Hitler’s ‘final solution’ for the Jewish problem. This response to Mrs Woodham-Smith’s work was not confined to Irish reviewers, nor even to imaginative authors like Mr Frank O’Connor, but cropped up repeatedly in English periodicals also, occasionally in articles by reputable historians.46

Among such reputable scholars, Lyons must have had in mind A.J.P. Taylor, the distinguished, if controversial, historian of modern Germany, whose review of The great hunger appeared in the New Statesman and was later reprinted under the title ‘Genocide’ in his Essays in English history. At times Taylor sounded just like the famous Irish revolutionary nationalist John Mitchel, whose genocide interpretation of the famine revisionists had long pointedly neglected. In the late 1840s, declared Taylor with a sweeping reference to the notorious German extermination camp, ‘all Ireland was a Belsen’. He then proceeded to insist that ‘the English governing class’ had the blood of ‘two million Irish people’ on its hands. That the death toll was not higher, Taylor savagely remarked, ‘was not from want of trying’. As evidence, he offered the recollection of Benjamin Jowett, the master of Balliol: ‘I have always felt a certain horror of political economists since I heard one of them say that the famine in Ireland would not kill more than a million people, and that would scarcely be enough to do much good.’47

Woodham-Smith herself was reasonably restrained in her conclusions, and Lyons absolved her of responsibility for what he saw as the emotionalism and the wholly inappropriate comparisons of the reviewers.48 But at the same time he accused her of other serious faults: vilifying Charles Trevelyan, the key administrator of famine relief, and exaggerating his importance; failing to place the economic doctrine of laissez-faire firmly in its contemporary context and glibly using it as an explanatory device without acknowledging the looseness of this body of ideas; and in general committing the cardinal sin of the populariser – choosing narrative and description over analysis. Admittedly, her merits as a populariser were great. ‘No one else’, conceded Lyons, ‘has conveyed so hauntingly the horrors of starvation and disease, of eviction, of the emigrant ships, of arrival in Canada or the United States, of the terrible slums on both sides of the Atlantic to which the survivors so often found themselves condemned.’ And if all that students wanted to know was ‘what happened in the starving time and how it happened’, then The great hunger would supply the answers. But they would simply have to turn elsewhere if they wanted ‘to know the reasons why’ – a rather unkind ironic word-play with the title of Woodham-Smith’s famous book about the British role in the Crimean war.49 Apparently, Lyons’s stinging criticisms of Woodham-Smith were widely shared by other members of the Dublin historical establishment. In University College, Dublin, in 1963 history students encountered as the essay topic of a final exam the dismissive proposition, ‘The great hunger is a great novel’.50

THE REVISIONIST CLASSIC

In saying that students of the famine who wanted to know the reason why would have to turn elsewhere, Lyons had in mind the academically acclaimed but much less famous book entitled The great famine: studies in Irish history, 1845–52. Edited by R. Dudley Edwards and T. Desmond Williams, two of the founding leaders of modern Irish historiography, this book was published in Dublin in 1956 (and in New York in 1957) after rather extraordinary editorial delays. Thanks to the detective work of Cormac Ó Gráda and the open-handedness of Ruth Dudley Edwards, the fascinating internal history of this collective and poorly managed but still highly important enterprise has recently been laid bare.51 Ironically, given the academic and revisionist halo that eventually came to surround it, this project had its origin in a suggestion made in the early 1940s by Eamon de Valera, then the taoiseach, to James Delargy (Séamus Ó Duilearga), the director of the Irish Folklore Commission. Offering modest government financial assistance, de Valera proposed the production of a commemorative volume in time for the centenary of the great famine in 1945 or 1946.52 If de Valera expected such a volume to have a nationalist and populist bias, he was to be sadly disappointed. It is not at all surprising to learn that de Valera, who liked to tax the British with seven or eight centuries of oppression, greatly preferred Woodham-Smith’s book, with its sustained attack on British policies and administrators, to the much more scholarly and restrained work edited by Edwards and Williams.53

The editors of and contributors to The great famine, whose work continues to be of lasting value in spite of its faults, could not be accused of emotionalism or of politicising their tragic subject. They appear to have been quite anxious to avoid reigniting old controversies or giving any countenance to the traditional nationalist-populist view of the famine. The overall tone was set in the foreword, where Kevin B. Nowlan soothingly observed:

In folklore and political writings the failure of the British government to act in a generous manner is quite understandably seen in a sinister light, but the private papers and the labours of genuinely good men tell an additional story. There was no conspiracy to destroy the Irish nation. The scale of the actual outlay to meet the famine and the expansion of the public relief system are in themselves impressive evidence that the state was by no means always indifferent to Irish needs. But the way in which Irish social problems so frequently overshadowed all else in the correspondence of statesmen testified in a still more striking manner to the extent to which the British government was preoccupied with the famine and distress in Ireland.54

The worst sins attributed by Nowlan to the British government were its ‘excessive tenderness’ for the rights of private property, its ‘different (and limited) view of its positive responsibilities to the community’, and its inevitable habit of acting ‘in conformity with the conventions of (the larger) society’.55 High politicians and administrators were not to be blamed; they were in fact innocent of any ‘great and deliberately imposed evil’. Instead, insisted Nowlan, ‘the really great evil lay in the totality of that social order which made such a famine possible and which could tolerate, to the extent it did, the sufferings and hardship caused by the failure of the potato crop’.56 In other words, no one was really to blame because everyone was.

That their collective volume essentially failed to answer the basic question of British responsibility was recognised by at least one of the editors at that time. Very soon after the book was published at the end of 1956, Dudley Edwards confided to his diary, ‘If it is [called] studies in the history of the famine, it is because they [the contributors?] are not sure all questions are answered. There are still the fundamental matters whether its occurrence was not due to the failure of the sophisticated to be alert.’57 By ‘the sophisticated’ I assume that at a minimum he means the political élite in Britain. Indeed, Edwards was aware much earlier, in 1952, that a merely mechanical yoking together of a series of specialist contributions on such subjects as politics, relief, agriculture, emigration, and folklore would ‘fail to convey the unity of what was clearly a cataclysm in the Butterfield sense’. The need to comprehend and to portray the disaster as a whole was, he felt, inescapable. If this were done, it would ‘also answer the question of responsibility, so unhesitatingly laid at England’s door by John Mitchel’.58 But in the end, when the book was published, no comprehensive narrative was provided, and partly as a result the powerful Mitchel’s most fully developed indictment – The last conquest of Ireland (perhaps), first published in 1860 – does not even appear in the bibliography. Given the bias already discussed, this omission was entirely appropriate.

MITCHEL’S CASE

Clearly, one reason why Mitchel repels modern revisionist historians is that his language in Last conquest is so vehement in tone and so extreme in the substance of its accusations. Occasionally, these accusations were personalised, as against Trevelyan. The famished children whom Mitchel viewed as he travelled from Dublin across the midlands to Galway in the winter of 1847 prompted the vitriolic remark: ‘I saw Trevelyan’s claw in the vitals of those children; his red tape would draw them to death; in his government laboratory he had prepared for them the typhus poison.’59 But usually Mitchel cast blame much more widely over British politicians and officials, employing bitterly ironic language that swept aside all restraint.60 In his view the aim and result of British ‘relief’ measures (‘contrivances for slaughter’, he called them) was really nothing else but mass death: ‘A million and a half of men, women, and children were carefully, prudently, and peacefully slain by the English government. They died of hunger in the midst of abundance which their own hands created. . . .’61 Mitchel was incensed by the government’s refusal to close the ports to the outward shipment of grain and livestock, and he skilfully exploited the issue – so skilfully that, as the last chapter of this book will show, he did more than any other nationalist writer to make the notion of an artificial famine a central part of the public memory of the disaster in Ireland and the Irish diaspora.62

Understandably, modern professional historians of Ireland have invariably found this aspect of the nationalist interpretation to be almost completely without merit, though at the popular level it has long persisted as an article of faith with a multitude of people. But the force of Mitchel’s case against the British government was (and remains) much stronger when he turned to consider the cost and character of those relief measures that he branded ‘contrivances for slaughter’. Repeatedly, he condemned the utter inadequacy of the government’s financial contribution and the gross unfairness in a supposedly ‘United Kingdom’ of throwing nearly the entire fiscal burden (after mid-1847) on Ireland alone. ‘Instead of ten millions in three years [1845–8], if twenty millions’, insisted Mitchel, ‘had been advanced in the first year and expended on useful labour . . . , the whole famine slaughter might have been averted, and the whole advance would have been easily repaid to the treasury.’63 Mitchel detected the genocidal intent of the British government not only in its refusal to accept the essential degree of fiscal responsibility but also in the relief machinery itself and in the way in which it was calculated to work. In his view the bureaucratic structures of ‘relief’ were murderous above all because of the goals they were intended to serve. Whatever relief was made available to the hungry and the starving, whether in the form of employment or of soup or of a place in the workhouses, was ultimately designed to break the grip of the Irish small farmer and cottier on his house and land, as a prelude to death at home or emigration and exile abroad. Mitchel was perfectly convinced – and convinced many others – that the consequences of British policy were not unintended but rather deliberately pursued, and he said so forcefully and repeatedly.64

Even though some of Mitchel’s accusations were far-fetched or wildly erroneous, others contained a core of truth or an important aspect of the truth. In this category, as later chapters of this book will demonstrate, were the murderous effects of allowing the grain harvest of 1846 to be exported, the refusal to make the cost of fighting the famine a United Kingdom charge, and the legislative decree of June 1847 that Irish ratepayers (landlords and tenants) must bear all the expense of relieving the destitute. The harsh words which Mitchel had for Charles Trevelyan, who effectively headed the treasury in London, do not seem – to me, at any rate – to have been undeserved, even if the professional historian would choose different language.65 After all, in the closing paragraph of his book The Irish crisis (1848), Trevelyan was so insensitive as to describe the famine as ‘a direct stroke of an all-wise and all-merciful Providence’, one which laid bare ‘the deep and inveterate root of social evil’. The famine, he declared, was ‘the sharp but effectual remedy by which the cure is likely to be effected. . . . God grant that the generation to which this opportunity has been offered may rightly perform its part. . . ’.66 These were hardly isolated musings. Thanks to the research of Peter Gray, we now appreciate how pervasive providentialist thinking was among the British political élite at the time of the famine, and how closely it was linked to central aspects of government policy towards Ireland during the crisis.67 According to the strand of providentialism espoused by Trevelyan and other British policy-makers of the time, the workings of divine providence were disclosed in the unfettered operations of the market economy, and it was therefore positively evil to interfere with its proper functioning.

The suggestion has often been made by revisionist historians that Trevelyan’s importance has been vastly exaggerated. This notion, however, is itself wide of the mark. Rarely has treasury influence and control been in greater ascendancy.68 As Gray observes, Trevelyan’s ‘control over Irish policy grew as the famine continued, and he imposed his own rigid moralistic agenda with ruthless enthusiasm’.69 What is true is that Trevelyan had a great deal of ideological company. As Gray hints here, Trevelyan was identified not only with providentialism and laissez-faire but also with what has come to be called ‘moralism’ – the set of ideas in which Irish problems were seen to arise mainly from moral defects in the Irish character. When many Britons of the middle and upper classes tried to take the measure of what was fundamentally wrong with Ireland before and during the famine, they strongly tended to ascribe to most Irish people flaws that they regularly attributed to the poor in Britain. In the case of the Irish, however, the intensity and scope of these flaws appeared to amount to national traits. Thus, notoriously, The Times of London was to declare early in 1847 that Britain faced in Ireland ‘a nation of beggars’, and that among their leading defects were ‘indolence, improvidence, disorder, and consequent destitution’.70 Trevelyan and other ‘moralists’, who were legion, believed passionately that slavish dependence on others was a striking feature of the Irish national character, and that British policy during the famine must aim at educating the Irish people in sturdy self-reliance.

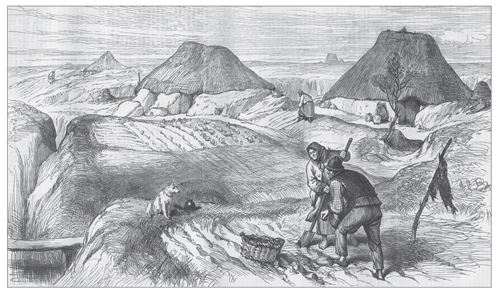

In this Punch cartoon of October 1846 entitled ‘Union is strength’, John Bull offers food and a spade to a distressed Irish labouring family and promises to put them soon ‘in a way to earn your own living’. Generosity and sympathy did mark the response of British public opinion at first, but there was a gradual shift towards tightfistedness and hardheartedness as the famine persisted, in spite of what was regarded in Britain as lavish public and private expenditure on relief. The cartoon title came to mock the bitter reality: Ireland from late 1847 was left to fend for itself financially in spite of the 1800 act of union between the two countries. (Punch Archive)

Even John Mitchel’s insistence on the perpetration of genocide becomes more understandable when certain crucial facts and their interrelationship are kept in mind. Among the lessons that ‘the most frightful calamities’ of 1846–7 had driven home, according to the incorrigibly blinkered Trevelyan, was that ‘the proper business of a government is to enable private individuals of every rank and profession in life to carry on their several occupations with freedom and safety, and not itself to undertake the business of the landowner, merchant, money-lender, or any other function of social life’.71 Admittedly, the massive public works and the ubiquitous government-sponsored soup kitchens had violated the doctrinaire laissez-faire views thus espoused by Trevelyan, but that is precisely the point: they were gross violations which very recent experience, as interpreted by Trevelyan (and Whig ministers) in late 1847, had shown should never be repeated. And of course they weren’t, even though the greater part of famine mortality was yet to come.72

THE AMENDED POOR LAW

As if to atone for its misguided profligacy through the summer of 1847, Russell’s Whig government then moved to fix almost the entire fiscal burden on Ireland by amending the poor law in June 1847. The 130 poor law unions into which Ireland was divided were each self-contained raisers and spenders of their own tax revenue; the poorest unions in the country were to go it alone, even though their ratepayers might well sink under the accumulating weight of the levies needed to support a growing mass of pauperism. It mattered not in the eyes of the British government whether this weak fiscal structure was really capable of keeping mass death at bay. What mattered was the supposedly universal and timeless validity of a then cherished economic doctrine. ‘There is’, declared Trevelyan in late 1847, ‘only one way in which the relief of the destitute ever has been or ever will be conducted consistently with the general welfare, and that is by making it a local charge.’73 It was on this principle that British policy rested from mid-1847 onwards, with the result that, as Trevelyan himself said (and said proudly), ‘The struggle now is to keep the poor off the rates’.74

Mitchel correctly emphasised the connections between the workings of the Irish poor law (as amended in June 1847) and the mass evictions, mass death, and mass emigration that marked the famine. Those connections will be thoroughly explored in a later chapter of this book. Here only a few points need be made. The amended poor law, the centrepiece of government ‘relief’ policy from September 1847 onwards, encouraged and facilitated wholesale clearances of tenants from many estates and greatly raised mortality rates in those districts of the south and west where mass evictions were concentrated. Numerous contemporaries drew attention to the ways in which clearances contributed materially to mass death. The prime minister himself, Lord John Russell, was in no doubt about at least some of the links between clearances and death.75 In fact, many educated people in Britain became aware, in varying degrees, of the pitiless severities in the working of the poor law system. But British cabinet ministers, politicians, and officials, along with Irish landlords, mentally insulated themselves against the gross inhumanity and often murderous consequences of evictions by taking the view that clearances were now inevitable, and that they were essential to Irish economic progress.76 The failure of the potato had simply deprived conacre tenants and cottiers of any future in their current status. ‘The position occupied by these classes’, proclaimed Trevelyan in The Irish crisis, ‘is no longer tenable, and it is necessary for them to become substantial farmers or to live by the wages of their labour.’77 But what if they could do neither?

Although a towering mass of human misery lay behind the twin processes of clearance and consolidation, Trevelyan (and many others) could minimise the human tragedy and concentrate on what they regarded as the economic miracle in the making. Among the signs that ‘we are advancing by sure steps towards the desired end’, remarked Trevelyan laconically in The Irish crisis, was the prominent fact that ‘the small holdings, which have become deserted owing to death or emigration or the mere inability of the holders to obtain a subsistence from them in the absence of the potato, have, to a considerable extent, been consolidated with the adjoining farms; and the middlemen, whose occupation depends on the existence of a numerous small tenantry, have begun to disappear’.78 Is it not remarkable that in this passage describing the huge disruption of clearance and consolidation, the whole question of agency is pleasantly evaded? Tenants are not dispossessed by anyone; rather, small holdings ‘become deserted’, and the reasons assigned for that do not include eviction. But whatever the reasons, the transformation is warmly applauded.

Thus there is no cause to think that Trevelyan would have disagreed with the Kerry landlord who affirmed privately in October 1852 that the destruction of the potato was ‘a blessing to Ireland’.79 This was by then the common view among the landed élite. Lord Lansdowne’s agent William Steuart Trench put the same point somewhat differently in September of the same year: ‘Nothing but the successive failures of the potato . . . could have produced the emigration which will, I trust, give us room to become civilised.’80 But the connecting line that ran from the blight to mass eviction, mass death, and mass emigration embraced the poor law system imposed by Britain. This is not to say that the amended poor law did not save many lives; it is to say that it caused many deaths, incalculable suffering, and a substantial part of the huge exodus. As the economist Nassau Senior was told in 1852 by his brother, himself an Irish poor law commissioner, ‘The great instrument which is clearing Ireland is the poor law. It supplies both the motive and the means. . . .’81 From the vantage point of the early 1850s, then, the famine experience and the British response seemed to make accusations of genocide rather plausible among many Irish nationalists, and the next half-century was to witness the consolidation and elaboration of the Mitchelite case.

PUBLISHING BOOM

If Mitchel’s full-blown genocide accusation is unsustainable, variants of what might fairly be called a nationalist or anti-revisionist interpretation have experienced a revival at the hands of professional historians during the unprecedented surge of research and writing about the great famine over the last decade. This surge has stemmed mostly from the official sesquicentennial commemoration of the famine which began in 1995 and concluded in 1997 – to make way for another commemoration of an earlier seismic episode in Irish history, the bicentenary of the 1798 rebellion. Academics have joined lustily in a variety of historical commemorations in recent decades, holding conferences and symposia, venturing into the public arena as lecturers and advisers to governments and private bodies, and publishing sudden torrents of books and articles. The sesquicentennial commemoration of the famine exhibited all the usual features of such clusters of events and some new ones besides (‘famine walks’, the rediscovery of famine graveyards, memorial plaques, pop concerts, and even a campaign for the beatification of the ‘famine martyrs’).82 The outpouring of publications was especially remarkable in contrast to the extraordinary paucity of professional writing on the famine since the 1930s, to go back no earlier. As one of the principal contributors to this great flurry of academic publication has rightly said, ‘more has been written to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the great famine than was written in the whole period since 1850’.83 And the river is still in flood, with some of the most significant contributions appearing well after the close of the commemoration, including Peter Gray’s Famine, land, and politics, Cormac Ó Gráda’s Black ’47 and beyond, and the multi-authored Mapping the great Irish famine, all published in 1999. The select bibliography at the end of this book emphasises the massive amount of historical writing about the famine during the past decade.

In passing from neglect to what some have seen as overweening attention, scholars of the great famine have frequently found merit in significant aspects of the nationalist interpretation. Admittedly, genocide allegedly arising from the ‘forced exportation’ of Irish food is not one of them. Christine Kinealy’s anti-revisionist efforts to breathe some life into this particular Mitchelite and nationalist view have not been seconded by other historians.84 Mary Daly, who still harbours certain definite ‘revisionist’ inclinations, was no doubt quite correct to insist in 1996: ‘Many facts are clear: the Irish famine was real, not artificial, food was extremely scarce; it could not have been solved by closing the ports; the charges of genocide cannot be sustained.’85 But this, of course, is hardly the end of the discussion, only a beginning. The very same research which has established the full dimensions of the great famine as an extraordinary subsistence crisis, with a colossal initial gap in the food supply beyond redemption by closing the ports to the export of Irish grain, has also established that heavy grain and meal imports went far towards closing that gap after 1847. According to Peter Solar’s laborious and invaluable calculations, overall Irish food consumption between 1846 and 1850 was only about 12 per cent less than in the years 1840–5.86

Could government action have closed this gap? The shortfall was admittedly much greater in 1846 and 1847 than it was later. Ó Gráda has estimated that the retention of all the grain exported in 1846 and 1847 ‘would still have filled only about one-seventh of the gap left by [the loss of] the potatoes in Ireland in these two crucial years’. But he also acknowledges that ‘a temporary embargo on grain exports coupled with restrictions or prohibitions on brewing and distilling – a time-honoured stratagem – or else a more vigorous public commitment to buying up and redistributing Irish and foreign grain in late 1846 and early 1847, might have alleviated starvation in these critical months’. Ó Gráda seriously doubts that a simple export embargo would have been politically feasible for several years in succession in the face of the likely resistance from Irish middling and large farmers who, riding above the disaster, were after all the ultimate exporters of the great bulk of the grain that left the country during the famine years. But this view, while reasonable enough, assumes what was undeniably the source of the problem: the refusal of the British government to treat Ireland as part of the United Kingdom and its famine as an imperial responsibility. After 1847 it would not even have required an embargo for the government to address the continuing crisis effectively, for that crisis was now not the outcome of an absolute shortage of food but a matter of mal-distribution, or (in the language of the distinguished economist Amartya Sen) of the weak ‘entitlements’ of the destitute to the greatly increased availability of Indian corn and meal. Thus Ó Gráda is surely right to conclude that ‘the persistence of destitution and famine throughout much of the west of Ireland during 1849 and 1850, despite plentiful supplies of food, would seem to fit the entitlements approach well enough’.87

The research of Christine Kinealy and others on the administration of relief, and especially on the operation of the amended poor law, has also helped to rehabilitate important parts of the nationalist interpretation. Her overall assessment at the conclusion of The great calamity (1994) amounts to a fairly scathing indictment of the whole approach of the British government to the Irish famine:

By implementing a policy which insisted that local resources must be exhausted before an external agency would intervene, and [by] pursuing this policy vigorously despite local advice to the contrary, the government made suffering an unavoidable consequence of the various relief systems which it introduced. The suffering was exacerbated by the frequent delays in the provision of relief even after it had been granted, and by the small quantity of relief provided, which was also of low nutritional value. By treating the famine as in essence a local problem requiring a local response, the government was in fact penalising those areas which had the fewest resources to meet the distress.88

This summation, quite consistent with the wealth of detail provided earlier in the volume, makes rather inexplicable the assertion of Mary Daly about the poor law in her 1996 examination of ‘revisionism’ in relation to the great famine: ‘Kinealy’s work does much to rehabilitate its overall reputation given the strictures of Woodham-Smith and others.’89 If Kinealy can be embraced as a revisionist, then the nationalist interpretation has really triumphed! What Kinealy’s book does bring out clearly is that some British poor law officials in Ireland, both in Dublin and at the local level, became increasingly critical of the policies pursued by civil servants (Trevelyan above all), cabinet ministers, and other politicians in London.90 Though they dissented, few of these officials resigned, but one who did – Edward Twistleton, the chief Irish poor law commissioner – left a searing record of the depth of his revulsion. He maintained in 1849 that though many were then ‘dying or wasting away’ in the acutely distressed western districts, ‘it is quite possible for this country [Britain] to prevent the occurrence there of any death from starvation by the advance of a few hundred pounds, say a small part of the expense of the Coffre war’.91 His resignation in March of that year was based on the grounds that ‘the destitution here [in Ireland] is so horrible, and the indifference of the House of Commons to it so manifest, that he is an unfit agent of a policy that must be one of extermination’.92

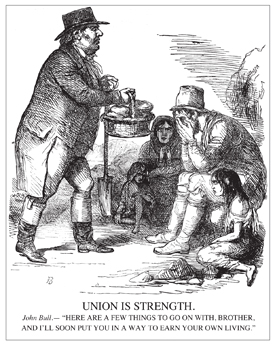

Evictions occurred on a massive scale during the famine and in the early 1850s, with the formal dispossession of some 250,000 persons from 1849 to 1854 alone. The rate of eviction varied greatly from one part of the country to another, with the western counties in the van. Clare and Mayo had the highest rates. Because the famine undermined or shattered the usual networks of community action and bonds of social solidarity, there was little violent resistance. This illustration of a single tenant vainly pleading against eviction in late 1848 may stand for the fate of hundreds of thousands. The sketch shows the tenant, his wife, and his daughter begging the landlord or agent for a reprieve, while bailiffs seize the tenant’s goods and soldiers overawe possible resisters. (Illustrated London News)

Also helping to rehabilitate central features of the nationalist interpretation has been the re-examination of the whole issue of the mass evictions, or clearances, at the centre of the famine experience. The clearances in two of the worst-affected counties – Clare and Mayo – have been the subjects of studies by Donald Jordan, Ignatius Murphy, Ciarán Ó Murchadha, and Tom Yager, though more research is still needed on these and other counties.93 In his magisterial account of landlord–tenant relations between the famine and the land war, William Vaughan emphasises how uniquely intense was the soaring rate of evictions in the late 1840s and early 1850s. He estimates that 70,000 evictions (of families) occurred between 1846 and 1853, and that almost half of these consisted of large clearances of tenants (over 400 clearances altogether), with ‘each one on average involving the removal of eighty families’. This enumeration, however, deals only with formal evictions and makes no allowance for the extraordinary number of informal evictions and involuntary surrenders which, as shown in Chapters 5 and 6 of this book, also marked these years, and it probably underestimates even the formal evictions of 1846–8 (before statistics began to be kept). Vaughan is right to stress that the incidence of dispossession was very uneven geographically, with formal evictions in Tipperary being almost twenty times more numerous in 1849–53 than in Fermanagh, the county with the fewest removals. But it does seem a little bloodless to conclude, as he does, that the estimated 70,000 formal evictions of 1846–53 ‘would not have threatened or even seriously modified the structure of rural society if they had been evenly spread throughout the whole country’.94

What is now clear is that extraordinary rates of eviction – formal and informal – in a few counties, and high rates in a half-dozen more, helped to solidify the idea of genocide in the Irish popular consciousness and especially among active, vocal nationalists. Voices of opposition to the clearances were not lacking in Ireland. In fact, what made it all the more necessary for landlords and government ministers to excuse, rationalise, or justify clearances were the persistent linkages made in the Irish press between mass evictions and mass death. Typical of many such comments was the Limerick and Clare Examiner, whose special correspondent was chronicling the depopulation in that part of the country. In May 1848 the paper protested vehemently that ‘nothing, absolutely nothing, is done to save the lives of the people – they are swept out of their holdings, swept out of life, without an effort on the part of our rulers to stay the violent progress of human destruction’. Significantly, the most active members of the anti-clearance lobby were Catholic priests and prelates. When their own parishioners were being evicted in droves, it is scarcely surprising that local priests felt compelled to denounce the ‘exterminating’ landlords whom they held responsible. A great deal of what we know about clearances in particular localities comes to us from the often detailed lists of evicted persons and accompanying commentaries supplied to the national or provincial press by parish priests and curates.95

It is also clear that in numerous cases evictions stimulated or strengthened specifically nationalist responses from the Catholic clergy. This tendency was generalised in a rather spectacular way by the British political reaction to the notorious assassination of the estate-clearing Roscommon landowner Major Denis Mahon in late 1847. As Donal Kerr has demonstrated in ‘A nation of beggars’? (1994), one of the most important books to be published on the famine in the past decade, this highly charged political episode was of great significance in the growing alienation of the Catholic priesthood and hierarchy from the British government and the British political world in general in the late 1840s and early 1850s. Charges in England following Mahon’s murder that Irish Catholic priests were conniving at assassination prompted seventeen of the bishops to protest with a ‘fierce anger’ against the absurdity and iniquity of these accusations in a common statement to Pope Pius IX in March 1848. ‘So bitter was the resentment revealed in the bishops’ protest’, declares Kerr, ‘that it was difficult to see how trust could be restored between them and the British governing class.’96 Priests throughout Ireland, regardless of their political hue, were equally appalled at this reaction in Britain to the clerical denunciation of evictions.

So much of what happened in Ireland in the late 1840s was the result of policy failures in London that the nationalist interpretation was bound to benefit from close study both of high politics there and of the general British political context. Indeed, for many years this was one of the most glaring lacunae in the entire historiography of the famine. Though Woodham-Smith had paid some attention to policy-making at the highest levels, the narrowness of her preoccupation with Trevelyan cast doubt over the general applicability of her conclusions and the validity of her severe strictures. Even as late as 1994 Christine Kinealy, a scholar who is not in any sense an apologist for British policies in famine Ireland, could suggest that there was almost a conspiracy organised by Trevelyan and a handful of other British civil servants – ‘a group of officials and their non-elected advisors. This relatively small group of people, taking advantage of a passive establishment, and public opinion which was opposed to further financial aid for Ireland, were able to manipulate a theory of free enterprise, thus allowing a massive social injustice to be perpetrated within a part of the United Kingdom.’97 In fact, as Peter Gray has shown in his magnificent recent book Famine, land, and politics and in a series of important recent articles, the views of Trevelyan and other leading civil servants in London were widely shared, and his domination of policy was the outcome partly of divisions within the cabinet and partly of the congruence of many of his attitudes with those of both some key cabinet ministers and a wide section of the educated British public.

BRITISH POLITICS AND THE FAMINE

Gray’s main achievement in Famine, land, and politics is to uncover as never before the workings of the British political system at its different levels, the interrelationships and frictions between the levels, and the attitudes that prompted action and inaction in the mid- and late 1840s. He shows that Trevelyan was allied with other ‘moralists’ within the cabinet, including Sir Charles Wood, the chancellor of the exchequer, and Sir George Grey, the home secretary, but that this faction was sometimes at odds with the ‘moderate liberals’ and the ‘Foxites’, with Lord John Russell, the prime minister, belonging to this last group.98 The ‘moderate liberals’, however, included the marquises of Clanricarde and Lansdowne and Viscount Palmerston, all three being great Irish landowners with hard-line views on the need for drastic consolidation of holdings. Even though Russell denounced clearances and supported various proposals for government intervention in Ireland, cabinet divisions often thwarted him and made a shambles of his ineffective attempts at leadership. Given the comprehensiveness and carefulness of his whole approach, Gray’s overall judgement on the Whigs’ stewardship from the autumn of 1847 through the end of the famine carries all the more authority:

The charge of culpable neglect of the consequences of policies leading to mass starvation is indisputable. That a conscious choice to pursue moral or economic objectives at the expense of human life was made by several ministers is also demonstrable. Russell’s government can thus be held responsible for the failure to honour its own pledge to use ‘the whole credit of the treasury and the means of the country . . . , as is our bounden duty to use them . . . , to avert famine and to maintain the people of Ireland’.99

Besides disclosing the inner workings of Russell’s government, Gray’s other principal achievement is to explore the main currents of public opinion in Britain in the late 1840s and to show how these currents constrained or forwarded the Irish policy prescriptions of ministers, civil servants, and politicians in general. He lays particular emphasis on the outcome of the general election of July 1847, which greatly increased the number of independently inclined radical MPs (to a total of eighty or ninety) in the House of Commons, giving them, at least potentially, the balance of power there. The radicals’ success in this election largely reflected middle-class industrial and commercial hostility towards large government expenditures on Irish relief and perceived government favouritism towards Irish landowners.100 The conclusion drawn by Russell from this electoral result spelled retrenchment in government outlays for relief: ‘We have in the opinion of Great Britain done too much for Ireland and have lost elections for doing so. In Ireland the reverse [i.e., losses there too, but for doing too little].’101 Gray also stresses the dampening effects on British generosity of both the British economic downturn of 1847–8 and the abortive Irish ‘rebellion’ of July 1848.102 But it is in his close examination of the ideological underpinnings of British politics that Gray is most original. He finds that ‘the ideas of moralism’ (which located the source of Irish problems in the moral deficiencies of the Irish character), ‘supported by providentialism and a Manchester-school reading of classical economics, proved the most potent of British interpretations of the Irish famine’. ‘What these ideas led to’, Gray forcefully concludes,

was not a policy of deliberate genocide, but a dogmatic refusal to recognise that measures intended ‘to encourage industry, to do battle with sloth and despair, to awake a manly feeling of inward confidence and reliance on the justice of heaven’, were based on false premises, and in the Irish conditions of the later 1840s amounted to a sentence of death on many thousands.103

British ‘moralism’ was deadly in another way. The strenuous objections of ‘moralists’ within and without Russell’s cabinet explain in part why the enthusiasm of some Whig ministers and many Tory protectionists for state-assisted emigration on a large scale was never translated into action in the late 1840s.104 ‘Moralists’ stoutly resisted public funding of emigration because, as Trevelyan put it in August 1849, ‘it would do much real mischief by encouraging the Irish to rely upon the government for emigration which is now going on at a great rate from private funds’.105 Here resided another grievous misfortune for famine Ireland. The study of Irish emigration has been one of the great ‘growth industries’ of recent Irish historical scholarship, and though the expansion was already much in evidence before the 1990s (the prize-winning Emigrants and exiles of 1985 by Kerby Miller was a special landmark), growth has continued at an impressive rate in the past decade, as many of the titles in the select bibliography at the end of this book testify. Much of this scholarship has been concerned in whole or substantial part with the famine period. Although the traditional nationalist interpretation of the famine depicted emigration as a plot concocted by Ireland’s ‘hereditary oppressors . . . who have made the most beautiful island under the sun a land of skulls or of ghastly spectres’,106 some recent students of both emigration and the famine have rightly emphasised that it was a reasonably effective form of disaster relief, and that if the government and Irish landlords had both made it financially possible for many more to leave Ireland for foreign shores, the famine death toll might have been very considerably reduced.107

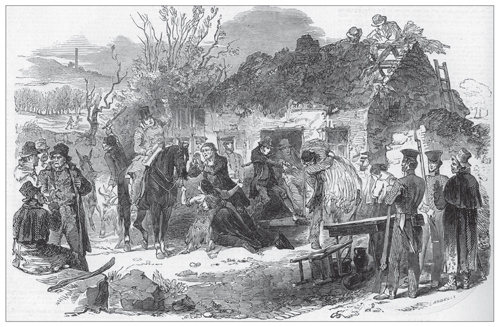

This sketch of a priest giving his blessing to a group of departing emigrants in 1851 should not be considered universally valid. At first, the greatly increased scale of emigration during the famine was accepted by the Catholic clergy, but gradually nationalist attitudes, clerical and lay, began to shift. The initial acceptance gave way to reservations, then to strong criticism of government policy and landlord action, and finally to full-blown condemnation of emigration as ‘forced exile’. By the early 1850s there were relatively few priests who would have challenged the assertion that emigration was ‘a devilish plot to exile the bone and sinew of the country’. (Illustrated London News)

EMIGRATION: NOT ENOUGH?

Though more than a million people emigrated during the famine itself, the problem was that an extremely high proportion of those at greatest risk – labourers, smallholders, and their families – lacked the means to emigrate on their own. This was recognised at the time even by some government ministers, such as the Irish viceroy Lord Clarendon, who wanted to ‘sweep Connaught clean’ of the smallest tenants (he mentioned a figure of 400,000 people) in the late 1840s through state-aided emigration, knowing that most of them could not depart on their own.108 Some proponents of assisted emigration pointed to what they regarded as the success of one government body – the commissioners of woods and forests – in sending about 225 people from a crown estate at Ballykilcline, County Roscommon, to New York in 1847–8.109 This case has been the focus of one of the best known emigration studies of recent years – Robert Scally’s The end of hidden Ireland (1995). Tracking these emigrants as closely as possible, Scally found that a substantial number of the 400 persons on the estate at last count fell victim to death, sickness, or other serious misadventure before ever setting foot on the emigrant ship in Liverpool, in spite of above-average expenditure per capita and much planning.110 But some readers of Scally’s fine study have objected that on the whole these emigrants were better off than many of those financed at lower rates by landlords, and that in any case assisted emigration on a much larger and well-financed scale, such as that which occurred in the Scottish Highlands in the 1840s with wealthy landlord backing, offered the possibility, never actualised, of escape for tens of thousands from the mass death imposed by the poverty trap.111