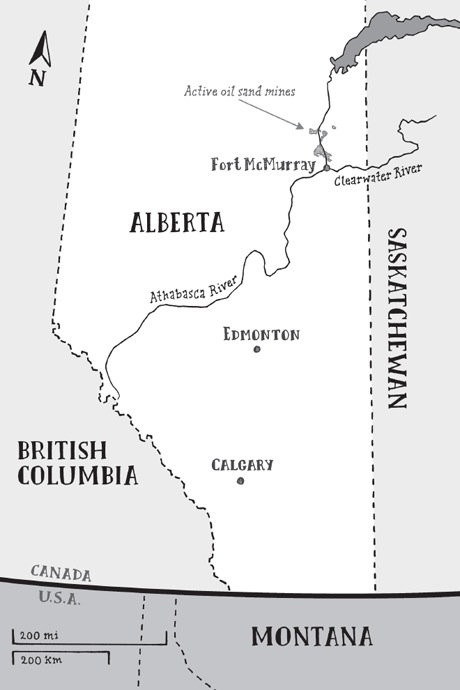

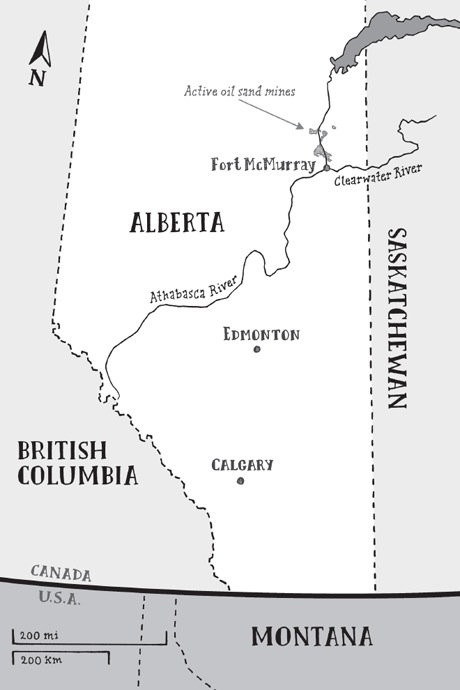

On April 28, 2008, a group of some sixteen hundred ducks landed on a lake near Fort McMurray, Canada. It was a warm day for early spring in northern Alberta, the temperature reaching into the mid-sixties. The ice on the water was still melting after the long winter. The ducks were heading for nesting grounds in the green expanse of Canada’s boreal forest—a vast band of coniferous trees and wetlands that stretches clear across Canada and that provides a summer home for half the birds in all North America.

Around these parts, though, a duck can’t safely assume that a lake is in fact a lake. This lake, for instance, was actually a huge tailings pond owned by the Syncrude corporation—“tailings pond” being a term of art in the mining industry for “waste reservoir.” As the birds touched down, they became coated with oily bitumen residue. Most of them sank. Others languished on the surface, waiting to be saved by human beings or videotaped by journalists. Of the sixteen hundred birds, fewer than half a dozen survived. Ducks of the world, beware of Alberta.

Syncrude had presumably hoped to keep its little duck holocaust private, but an anonymous tipster reported the incident and, before the day was out, the company had a full-blown public relations disaster on its hands. “Hundreds of Ducks Dead or Dying after Landing on Syncrude Tailings Pond,” reported the Western Star, while the Spectator ran the cheeky “Tar Pond Dooms Ducks to Death.” Within days, the scandal grew from mere corporate misfortune—“Syncrude in Hot Water over Duck Disaster” (Windsor Star)—to provincial government headache—“Duck Disaster Sinks Alberta Government’s Credibility” (Calgary Herald)—to a matter of national import that demanded the prime minister’s attention—“Harper Promises to Investigate Dead Ducks in Northern Alberta” (CBC).

This, then, is Canada—perhaps the only country where ducks have national, even geopolitical, significance.

But this isn’t because the Canadian character is somehow uniquely sensitive to the welfare of its waterfowl. It’s because the sixteen hundred—long may their memory live—had, with their deaths, scratched a festering sore on the Canadian national psyche. They had landed—and died—in something larger than a lake. Larger than a tailings pond. They had hit a grim bull’s-eye in the world’s largest and most controversial energy project, in the Middle East of the Great White North, in the cauldron of our energy future. They had landed in oil sands country.

Canada lives in the imagination of the United States as a benign, continent-size footnote, the brunt of conservative jokes about invasion and annexation, and the object of liberal daydreams about socialized medicine and sensible bank regulation. If there is an overarching consensus among Americans about their cousins to the north, it is that they are like Americans but nicer, probably smarter, and more loving of hockey.

Less well known is that Canada is a towering, earth-shaking, CO2-belching petroleum giant. Let us keep our stereotype that Canadians are mild-mannered, but in terms of oil there is nothing moderate about them. They have it. With something like 175 billion barrels’ worth hidden under the ground up there, the country is second in the world only to Saudi Arabia in proven petroleum reserves. The United States’ number-one single provider of foreign oil isn’t someplace in the Middle East. It’s Canada.

A secret joy must surge through the heart of the US economy at this fact. Here on our very doorstep is a Persian Gulf without the Persians. A Saudi Arabia without the Saudis—or the Arabians. And Canada literally advertises this fact. In 2010, the Alberta government bought time on the huge screens of Manhattan’s Times Square. “A good neighbour lends you a cup of sugar,” one ad read. “A great neighbour supplies you with 1.4 million barrels of oil per day.” It’s enough to make modest, climate-change-fearing Democrats want to build pipelines.

Those 175 million barrels, though, come with a 170-billion catch. Most of Canada’s oil—half of what it produces today and 97 percent of what it expects to produce in the future—isn’t in the form of liquid petroleum, ready to be pumped out. It’s oil sand, a thick, grimy sludge buried underground. And it takes more than sticking a straw in the ground to drink this particular kind of milkshake. It takes the world’s largest shovels, digging vast canyons out of what was once Alberta’s primeval forest; and the world’s largest trucks, delivering huge quantities of the sticky, black sand into massive separators that need insane amounts of heat and water to boil the sand until the oil floats out of it, leaving behind—not incidentally, if you’re a duck—unfathomable quantities of poisonous wastewater, which are then stored in tailings ponds of unusual size.

Got it? Environmentalists call it dirty oil, as if the stuff that comes out of the ground in Kuwait were somehow clean. But oil sands oil isn’t dirty just because it requires strip-mining on a terrifying scale, or because it generates entire lakes of waste. It’s also energy-intensive: you have to spend a lot of energy to separate and process the oil, much more than if you were simply pumping petroleum out of a well. So if you’re passionate about carbon dioxide emissions and climate change—passionate about avoiding them, that is—oil from oil sands should give you the creeps. When you burn it, you’re also burning all the energy that was used to produce it. The technical term is double whammy.

Engineers in the audience may argue that in terms of CO2 emissions, oil sands are at worst a 1.25 whammy, depending on how you run the numbers. Nevertheless, a movement has coalesced around the goal of stopping oil sands development, with environmentalists determined to make Canada stop digging new Grand Canyons in its backyard. Leave the sticky stuff in the ground, they say, reasoning that, with the world already suffering for our overuse of fossil fuels, this is no time to be developing a new source.

But it’s hard to hear that argument over the incredible grumbling sound coming from the collective stomach of the United States. It sees Canada’s oil as a possible route to so-called energy independence, which is another way of saying “oil without Muslims,” and it wants nothing more than for Canada to rip the green, boreal top right off the entire province of Alberta and shake all that black, sandy goodness directly into a refinery. And that drives environmentalists batshit crazy with rage.

Fort McMurray lies in a splendid isolation of forest and swamp, nearly three hundred miles north of Edmonton, the provincial capital and nearest major city. As with most boomtowns, it’s tempting to call Fort McMurray a shithole, but its attempt at wretchedness is halfhearted. For every corner of town that is dingy or low-rent, there is one that is tidy and clean. For example, Franklin Avenue: there is the Oil Sands Hotel, its yellow sign illustrated with large, orange oil drops. A narrow marquee boasts, CHEQUES CASHED, LOW RATES, RENOVATED ROOMS 99.00, ATM IN LOBBY, EXOTIC DANCERS MONDAY-SATURDAY 430-1AM. Across the way, as counterbalance, are the city hall and provincial buildings, a pair of sleek brick cubes that project an orderly municipal competence. At seven and nine stories, they are the tallest things in town. The next block down you’ll find the Boomtown Casino, busy even at midnight on a Tuesday, as the people of Fort McMurray feed their oil sands money into slot machines.

Downtown sits on the triangle of land where the Athabasca and Clear water Rivers converge and run north. But Fort McMurray is growing. Just across the Athabasca, a loop of fresh suburbs three times the size of downtown sprawls up the hill. In the eight years preceding the global economic slowdown of 2008, the city’s population nearly doubled, to about a hundred thousand people. Housing is therefore exceedingly tight in Fort McMurray, and prices are closer to what you might expect in Toronto than in some town a five-hour drive from anywhere. Places to live are in such short supply, and the population drawn by oil sands work so transient, that some twenty-five thousand people—nearly a quarter of all residents—live in work camps provided by the oil sands companies. Which is to say, they don’t really live here at all.

I arrived on a broad summer day, the sky smooth and bright and warm. I was staying with Don and Amy, an affable couple I had contacted through friends. Along with a teenage son, they lived in a two-story house in one of the recently built suburbs. Don was tall and thoughtful and wore socks with his shorts. Amy was small, dark-haired, and sprightly in a way that made her seem much younger than she was. They were in the full flower of middle age, spending their free time hiking and bicycling when the seasons allowed it. Hospitality seemed to come to them as a natural side effect of owning a house, and although they had no idea who I was or why I was there, they gave me my own bedroom upstairs and let me have the run of their fridge.

They both worked for oil sands companies: Amy for Suncor, Don for Syncrude. These are Canada’s two primary oil sands companies, and each reliably pulls in billions of dollars in annual profits. Amy did leadership training, while Don was an engineer.

What, they wondered, was I doing in Fort McMurray?

I didn’t want to say I had come to their town to see how the very two companies they worked for were ruining the world. It’s this phobia I have about not seeming like a total asshole. So I gave them the long, squirmy version, something about environment and industry and seeing for myself and—

“Well,” said Amy brightly. “We both work for the dark side.”

Don scratched his head. “I don’t know if you heard about our duck episode.”

The rivers and forests that cradle Fort McMurray offer plenty of invigorating outdoor activities to visitors looking for that sort of thing. By the looks of it, you could do some great hiking or buzz the river on a Jet Ski, and I’m sure there’s moose around that you could shoot. But the pollution tourist goes to Fort McMurray only for the mines.

It was a homecoming of sorts. I was born in Alberta (in Calgary), and although I left before I was two years old, it had always lingered in my imagination as that magical place—the place I’m from. This was my first time back in the province, and I intended to celebrate by seeing some torn-up planet.

I will admit to a certain excitement about it all, even though the responsible attitude, as a sensitive, eco-friendly liberal, would have been one of grave concern, or even horror. But I’m also the son and grandson of engineers: intelligent, bullshit-allergic men out of Alaska and South Dakota, men who lived by their knowledge of roads and of pipelines, and of rocks, and of how things get done. And though I inherited barely a trace of their common sense, I honor them how I can. How else to explain my almost sentimental enthusiasm for heavy infrastructure and industrial machines?

You could say, then, that I came to Fort McMurray with conflicted feelings about the oil sands, unsure of just how much filial gusto and faux-local pride were appropriate at the scene of a so-called climate crime. But this could be said about Canada in general. I was merely a walking example of the country’s love-hate relationship with its own resources. The modest northern country where Greenpeace was founded had been declared an “emerging energy superpower” by its own prime minister, and in a spasm of vehement ambivalence, Canada was both pioneering the era of dirty oil and leading the fight to stop it.

Suncor’s and Syncrude’s main operations are located a quick jaunt up Highway 63, which runs parallel to the Athabasca, past hummocks of evergreen. About twenty-five miles out of town, the air starts smelling like tar. Suncor’s business is hidden from the road, but Syncrude shows a little leg. As you get close, the trees disappear, and you pass a long sandy berm; one of Syncrude’s flagship tailings ponds sits on the other side, a shallow lake of glassy wastewater.

I rolled down the window to let in the breeze, tarry and warm. The cracking thuds of cannon fire punctuated the air. It was the bird-deterrent system, the one that Syncrude had been a little slow to deploy in the spring of the previous year.

Let us hope that ducks find these noises either helpful or terrifying. Personally, I found it hard to tell where they were coming from. Had I been a duck, I would have wanted to land, to get my bearings and figure out just what the hell was going on. This also would have afforded me a closer look at the other bird-deterrent: a sparse posse of small, flag-like scarecrows that decorated the shore. Several more of the ragged little figures floated on lonely buoys in the middle of the lake.

The mines themselves were nowhere visible, but at the north end of the lake rose the Syncrude upgrading plant, the flame-belching doppelgänger of Disney’s Enchanted Kingdom, built of steel towers and twisting pipes, crested with gas flares and plumes of steam. A hot, wavering stain of transparent yellow rose from one smokestack, drawing a narrow stripe across the sky.

Oil sands contain a heavy form of petroleum called bitumen, which must go through several stages of upgrading at a plant like this before it can enter a refinery. But before it can even be upgraded, it must be separated from the vast quantities of sand that are its host. This first step takes place mine-side, where the sand is mixed with water and then heated, separating out the layer of bitumen that clings to each grain of sand. You have here two issues: the use of massive amounts of water—in this case drawn from the Athabasca River—and the incredible volumes of natural gas required to heat it.

The separated bitumen is then piped to the upgrading plant, where—using yet another unimaginable amount of energy—it is put through a series of distillations and cracking processes to break it down into smaller, more manageable hydrocarbons. Only then can the result—called synthetic crude oil—be sent off to a refinery for the production of gasoline, jet fuel, and ziplock bags.

I hung a left, following the loop that would take me past the front gate, around the tailings pond, and back toward town. Just west of the plant was the sulfur storage area, though to call it a “sulfur storage area” is like calling the pyramids a “stone storage area.”

One byproduct of Syncrude’s industrial process is a monumental quantity of sulfur, for which it has neither a use nor a market. So it stores the stuff, pouring it into solid yellow slabs, one hulking yellow level on top of the last, building what is now a trio of vast, flat-topped ziggurats fifty or sixty feet tall and up to a quarter mile wide. Like everything else around here, they may be some of the largest man-made objects in history—but I had never heard of them before. A pyramid of sulfur just isn’t news, I guess. They are less scandalous than a city-size hole in the ground, and only a very determined duck could get itself killed by one.

One day, though, Syncrude or its successors will see these vast—huge, monumental, gargantuan, monolithic—objects for the opportunity they are. Tourists of the future will summit their grand steps, and stay in sulfur hotels carved out of their depths, and sip yellow cocktails, and attend championship tennis matches at the Syncrude Open, for which the players will use blue tennis balls, for visibility on the sulfur courts. Thousands of years later, explorers bushwhacking through the jungles of northern Cameximeriga will stumble onto them and be dazzled by the simplicity of our temple architecture, at once brutal and grand, and will speculate about what drove us to worship sulfur above all other elements, and will see that the pharaohs were nitwits.

Although the mines sit at a breezy remove, their presence is felt everywhere in Fort McMurray. The economy and community thrum in tune with the ceaseless project of ground-eating. As you meander the streets, you begin to feel that you are an iron filing oriented along the field lines emanating from an immense subterranean magnet, and that everything and everyone in town is pointed toward it: the new bridge over the Athabasca, built to withstand the load of heavy equipment being transported to the work site; traffic lights that can be swung sideways out of the roadway to let oversize loads pass unhindered; the local high school (mascot: the Miners; motto: “Miner Pride”); the old excavating machine sitting on the lawn of Heritage Park.

You feel it standing on a wooded bluff overlooking the river, where the air stinks of bitumen oozing naturally out of the hillside, and where nearly a century ago the first hopeful entrepreneur tried to boil money out of oil sands. And you feel it downtown at the Tim Hortons, where white pickup trucks line up around the corner to get their coffee and doughnuts. Each white pickup truck carries someone on his way to work at the mines, and each white pickup truck has a tall, whiplike antenna sprouting from its bed, and they are not antennas but safety flags. Without one, even a large pickup truck may go unnoticed by the behemoth sand haulers in the mine, and be crushed.

Even at leisure, people in Fort McMurray live out an echo of their industry, taking their minds off the noisy machines of the mines by churning through the countryside on other noisy machines, like all-terrain-vehicles and snowmobiles (known as sleds).

“Ninety percent of people who live here have at least one ATV or sled,” said Colleen, the young woman behind the counter at the off-roading store. She and her colleague Adam were Fort McMurray natives, rarities in a city overrun by outsiders coming for work, and they had a blasé defensiveness about their hometown. Colleen seemed almost to rue the economic boom that had transformed it. “The recession sucks and all, but in ways it’s amazing,” she said. “Now you can go to a restaurant and not wait three hours. You can get a doctor’s appointment. Before, if your car broke down, it would take nine weeks to get it fixed. The quality of life was getting really low before the recession happened. Everything was a struggle.”

But that didn’t mean they thought the oil sands themselves were a bad thing. “Fort McMurray is what’s powering all of Canada, and we don’t get the recognition,” Colleen said, picking up a tiny brown dog bouncing at her feet. “I think that whole ‘dirty oil’ thing comes from a lobbying group in Saudi.”

“The ducks,” Adam said, completing the conspiracy theory.

Colleen snorted. “Yeah, fuck! There’s so many more important things. Like consumer waste!”

Through Fort McMurray Tourism, anyone who signs up a day ahead and forks over forty bucks can take an oil sands bus tour. Oil sands bus tour—are there any four words more beautiful in the English language? Someone was finally seeing the light on this pollution tourism thing. I signed up.

The bus tour didn’t leave until the following morning, so I had a lonely afternoon to kill. I called my girlfriend. The Doctor. She always knows what to do in these situations. She has a peculiar kind of common sense that includes the possibility that spending your days roaming oil sands mines and nuclear disaster sites might be a good idea.

“Remember,” she said over the phone, “you’re supposed to be on vacation.”

Right! I was a tourist. And although the world’s industrial eyesores and ecological calamities generally languish unattended by gift shops and welcome centers, Fort McMurray is a forward-thinking town in this regard. I made for the Oil Sands Discovery Centre, a family-friendly museum for those interested in the local industry.

The OSDC represents some of the best industrial propaganda in the world. (Which I mean as a compliment. You try writing the brochure for Mordor.) Its gift shop is a gift shop among gift shops, an emporium thick with toy giant dump trucks, kid-size hard hats, watercolor prints of gigantic machines, and truck-themed socks. I grabbed an armful of goodies. At the register, I made the find of the day in a bin of impulse buys: a tiny, plush oil drop with yellow feet and googly eyes. Who knew petroleum could be so adorable?

Into the exhibits, where I spent the next several hours in a state of fizzing excitement over scale models of dragline shovels and bucket-wheel extractors, over containers holding liquid bitumen in different states—room temperature, heated, diluted—with rods to stir the stuff and feel the different viscosities. Not to mention the 150-ton oil sands truck parked inside the exhibit hall. I climbed two stories up, into its cab, and sat in the driver’s seat, wrenching the steering wheel back and forth.

And now let us praise the Dig and Sniff, in which a small mound of raw oil sand is displayed under a plastic dome. The Dig and Sniff invites you simply to dig, using the rod built into the display—and then, having dug, to sniff, through the small opening in the dome. Dig and Sniff! With a name of such economy and force, it commands you to action, granting you a direct experience—modestly tactile, safely olfactory—of the oil sands themselves.

A young boy worked the scraper. “This thing is cool!” he cried, sticking his nose into the dome. “Dad, come smell the oil sand! The Discover Center’s fun.” We were living inside a commercial for the OSDC. I took my turn at the stand, ready to get down to business.

I dug. I sniffed.

Frankly, it didn’t smell like much. Maybe it needed a fresh batch of sand. But had I not already learned something? That oil sand may sometimes lose its aroma?

You could be forgiven for assuming—it would be weird if you didn’t—that the OSDC was created by the oil sands companies themselves, as a temple to their own name. But among its many triumphs in industrial propaganda, surely the greatest is that it is actually a government facility, operated and administered by the province of Alberta itself. You can draw your own conclusions about what this seamless collaboration says about the relationship between oil and government around these parts.

Underneath all the excitement, though, there was a sour note—a defensive, self-conscious tone that sometimes crept into the wall copy. I could feel the exhibit designers grudgingly trying to account for that one spoilsport in each group, the one who would be asking over and over about the trees, and the rivers, and the ducks.

Toward the end of the galleries, past a backwater of displays about environmental responsibility and the future of clean energy and other boring crap, I found the Play Lab, a colorful area partially screened off from the rest of the hall by a metal space-frame. Child-size tables and chairs sat in the center of the room, attended by a wardrobe of hard hats and jumpsuits available on loan to the tiny oil sands engineers of tomorrow.

Ignoring the cues that I fell somewhat outside the Play Lab’s target demographic, I charged in, blazing my way through the PUMP IT exhibit—a wall of clear plastic pipes with valves to twist and a crank to turn—before settling in for a spell at DIG IT, which featured a pair of toy backhoe shovels and a trough filled with fake oil sand.

Neeeat!

The last section of the Play Lab was GUESS IT, a large grid of spinning panels printed with questions on one side and answers on the other. Somewhere an exhibit designer, worried about how much fun the rest of the Play Lab was, had caved in to the didactic urge. I read the first panel.

Bitumen is a very simple molecule. True or false?

Duh! We’re talking about hydrocarbons, here. False. Next question.

Oil sand is like the filling in a sandwich. True or false?

Uh, true?

True. The top slice is overburden, oil sand is the gooey filling, and the bottom slice is limestone. Yummy!

I no longer had the lab to myself. An elderly couple had entered and, after a cursory look at the shovels, were now having a go at PUMP IT. I turned back to GUESS IT.

Who is responsible for protecting the environment? a) the government, b) the oil sands companies, c) everyone.

It was that defensive tone. I didn’t need to turn the panel to know what GUESS IT wanted me to say. The only question was whether children were really the Play Lab’s target audience after all.

The highway north of Fort McMurray is so small, relative to the thousands of workers who need to get to the work sites every day, that traffic can be terrible, especially during shift changes. So the oil sands companies hire buses to ferry workers to and from town. Ubiquitous red and white Diversified Transportation coaches ply the highway in pods. That an industry partly responsible for Canada blowing its emission-reduction goals has a thriving rideshare program is just one of the tidy, spring-loaded ironies that jump out at you here.

The Suncor bus tour leaves from in front of the OSDC—I stole in for a quick taste of the Dig and Sniff—and it employs one of those same Diversified buses, re-tasked for our touristic needs. Mindy, our perky young tour guide, popped up in front and asked us to buckle our seat belts. “Safety,” she said, “is one of our number-one priorities.” The driver gunned the engine and we were off, about to be taken, Universal Studios-style, through an open wound on the world’s single largest deposit of petroleum. What soaring cliffs and hulking machinery did the day hold for us?

The bus was nearly full, mostly with families and seniors—people who looked like they had seen the inside of a few tour buses. A quartet of old ladies giggled like they were on a Saturday-night joyride. Sitting next to me was a Mr. Ganapathi, an old Indian man with a single, twisting tooth jutting from his lower jaw.

“You are married?” he asked.

I wasn’t, I said. But I thought of the Doctor. It wasn’t a bad idea.

By now we were passing along the eastern edge of the large tailings pond in front of Syncrude.

“Is this where all those ducks got killed?” a man asked his wife.

“Oh, we’ve had more fuss over those ducks!” she said.

There had indeed been more fuss. The governments of Canada and Alberta had decided to prosecute Syncrude for failing to repulse the ducks from the tailings pond. There would be a not-guilty plea, and complaints from Syncrude that it was being unfairly prosecuted for what amounted to a mistake but not a crime, and counter-complaints from environmentalists that Syncrude was getting off easy. In the end, Syncrude would be found guilty and fined $3 million—$1,868 Canadian for each duck. And if those sound like expensive ducks, keep in mind that in 2009 Syncrude made $3 million in profit every single day.

We stepped down from the bus near the Syncrude plant—it hissed in the distance—to visit a pair of retired mining machines. You needn’t take the bus tour to see them, though, as they are probably visible from space. I had never seen such machines. A dragline excavator stood on the right; on the left, a bucket-wheel reclaimer.

These days, oil sands mining uses shovels and trucks in a setup that has a nice scoop-and-haul simplicity to it. But this system is relatively recent. Previously, companies used a system of draglines, bucket wheels, and conveyor belts. With a dragline excavator (a machine probably bigger than your house), a bucket-like shovel hanging on cables from a soaring steel boom would gather up a bucketful of sand—and we’re talking about a bucketful the size of…the size of…hell, I don’t know. What’s bigger than an Escalade but smaller than a bungalow? Big, okay? The dragline would swing around, using the huge reach of the boom, and drop the sand behind it. It would then inch along the face of the mine, walking—actually walking—on gigantic, skid-like feet, repeating the process over and over, leaving behind it a line of excavated sand called a windrow.

Then the reclaimer would come in, turning its bucket wheel through the sand in the windrow, lifting it onto a conveyor belt on its back, which fed another conveyor belt, and another, transporting the sand great distances out of the pit. There were once thirty kilometers’ worth of conveyor belts operating in Syncrude’s mine, and if you’ve ever tried to keep a conveyor belt running during a harsh northern winter—who hasn’t?—you’ve got an idea of why they finally opted for the shovel-and-truck method.

To approach the bucket-wheel reclaimer was to slide into a gravity well of disbelief. It was difficult even to understand its shape. It was longer than a football field, battleship gray, its conveyor belt spine running aft on a bridge large enough to carry traffic. The machine’s shoulders were an irregular metal building several stories tall, overgrown with struts and gangways and ductwork, hunched over a colossal set of tank treads. A vast, counterweighted trunk soared over it all, thrusting forward a fat tunnel of trusses that finally blossomed into the great steel sun of the bucket wheel.

The wheel itself was more than forty feet tall, with two dozen steel mouths gaping from its rim, each worthy of a tyrannosaur, with teeth as large as human forearms. I stared up at it, nursing a euphoric terror, imagining how it once churned through the earth, lifting ton after ton of oily sand as it went. There was something wonderful about the fearsome improbability of the reclaimer’s existence. It was the bastard offspring of the Eiffel Tower and the Queensboro Bridge, abandoned by its parents, raised by feral tanks.

As my tourmates took pictures of one another standing in front of the behemoth, I walked back to the bus, where the driver was standing with his hands in his pockets. His name was Mohammed. The Suncor bus tour was only a minor part of his job. He spent most of his days ferrying workers to and from the mines. When I asked why he didn’t choose to drive one of the big trucks instead of a bus, he told me he wasn’t interested.

“But you could make a lot of money,” I said. The salary for driving a heavy hauler started at about a hundred thousand dollars—more if you worked a shovel.

He smiled. “The pollution. Especially at the live sites, Suncor and Syncrude.” He thought the air coming off the upgrading plants was bad for your health.

“But you breathe that air anyway,” I pointed out. “You drive onto those sites all the time!”

He laughed. “Yeah!”

The supposed centerpiece of the Suncor bus tour is of course Suncor itself. We entered from the highway, the air sweet with tar, and drove toward the Athabasca River into an area invisible from the road. My oil sands fever was reaching its crisis. The upgrading plant slid into view, a forest of pipes and towers similar to the Syncrude plant, but nestled next to the river in a shallow, wooded valley.

It was getting hard to pay proper attention to the scenery. Mindy had been keeping up an unrelenting stream of patter, a barrage of factoids that, despite its volume, managed to be completely uninformative. I found it difficult to follow her, even with my inborn enthusiasm for pipes and conveyor belts and giant cauldrons of boiling oil.

The green building houses the fart matrix. It uses 1.21 gigawatts of electricity every femtosecond.

The what matrix? Wait, which tower was—

…three identical towers of different sizes on the far side of the plant—can everybody see?

No, wait, which?

Good. Those are where the natural solids ascend and descend twenty-one times per cycle, each cycle producing ten metric tons of nougat, which is sold to China, because it can’t be stored so close to the river. The interiors of the towers have to be cleaned every two weeks using high-pressure ejaculators. Wow!

As we passed over the river—the river from which Suncor extracts about 180 million gallons of water per week—Mindy threw us a few bones of actual information. One point five million barrels of bitumen come out of the oil sands every day, she said, and Suncor had four thousand employees working on the project, which ran twenty-four hours a day, 365 days a year.

Underneath the avalanche of information, we were becoming dissatisfied. When would the drive-by of the upgrading plant and the mine’s logistical centers end and the actual oil sands tour start?

“Are we going to get close to one of these trucks?” growled a man in the back.

Mindy smiled. “I’m going to try!” she said. But of what her trying consisted, we will never know.

The bus continued down the road, past a few nice pools of sludge, the occasional electric shovel dabbling in the muck, and a couple of flares. In a bid to drown our curiosity before we mutinied, Mindy had begun a spree of pre-emptive greenwashing. Suncor was required by law, she told us, to “reclaim” all the land it used, meaning it was supposed to restore it, magically, to its state before the top two hundred feet of soil was stripped off and the underlying oil sands pulled out. As for the Athabasca River, if we were worrying about whatever it was that everyone was worrying about, we shouldn’t.

“We’re very limited in terms of what we can take during times of low flow in the river,” she said.

Thank goodness. And had we noticed all the trees? Suncor had already planted three and a half million trees, she chirped. There were Canadian toads, Bufo hemiophrys, living fulfilling lives on this very land.

We had reached the far outside edge of the mine—a dark rampart of earth. A huge chute was built into the embankment—it was the hopper that fed the oil sands into the crusher. It sat distant and lonely, unvisited. Mindy checked her boxes as we passed: hopper, crusher, building, pipe, and we left it behind. The bus parked and we were allowed to descend, for the inspection of a large tire sitting in the parking lot of the mine’s logistical headquarters.

We weren’t going to get the merest peek into the mine. Here on the oil sands bus tour, we weren’t going to see any trucks in action, any shovels, any actual oil sands. Here I was, ready to embrace some corporate PR with open arms, and even I thought it sucked.

The air reeked of tar. I had a headache. We got back on the bus. Mindy had some more information for us, something about how every ton of oil sand saves a puppy. She did not seem to have any realistic enthusiasm for oil sands mining, only a plastic version of the touchy, defensive pride endemic to the entire venture of oil sands PR. It’s just distasteful to watch an oil company try to prove that it is not only environmentally friendly but also somehow actually in the environmental business. Instead of straight talk from a man with a pipe wrench, we have to tolerate oil company logos that look like sunflowers, and websites invaded by butterflies and ivy. (As of this writing, www.suncor.com presents the image of an evergreen sapling bursting through a lush tangle of grass.) Who are they trying to convince? Themselves?

On the way back to the upgrading plant, I noticed some activity next to the hopper, on the high rampart above the extraction facility. There were a pair of haulers backing toward the chute, each piled high with oil sand.

I clambered over Sri Ganapathi, straining for a clear view through the far side of the bus, snapping pictures as one of the dump trucks began to raise its bed to drop its cargo into the chute. But as it did, we passed behind a building and the scene disappeared. Mindy was going for the green jugular, telling us how Suncor had planted so much vegetation on its land that deer came to live there.

“There’s no hunting allowed,” she said. “So they’re pretty happy.” Suncor, you see, is not a multibillion-dollar petroleum company, but a haven in which deer and toads can live in peace. I wanted to spit.

The view came clear and I saw the second truck. Four hundred tons of sticky, black earth—a solid mass as large as a two-story building, and enough to make two hundred barrels of oil—slid smoothly off its upturned bed and down the maw of the hopper. I had the sensation of having seen an actual physical organ of the animal otherwise known as our voracious appetite for fossil fuels. The appetite belongs to a body—a body with many mouths, some of them built into the sides of open pits in Alberta.

The trucks lowered their beds, heading out for the next load, and the next. I had seen the human race take a tiny bite out of the world. The bus drove on. Nobody was watching.

“So, are we raping the planet?” asked Don.

We were sitting in the living room.

Based on the morning’s utter bust of an oil sands bus tour, I said it was hard to declare with any certainty whether he and Amy were in fact raping the planet. I did hint, though, that there was room for competition in the oil sands bus tour niche.

After so much mealymouthed blather on the tour and at the OSDC, it was refreshing to talk to Don. But even he seemed fundamentally ambivalent. Don was an oil sands engineer, but he also had a degree in environmental science. He had begun his career on the reclamation side, and he talked eagerly about what was possible with a former mine site—even if his own company had only begun to reclaim the areas it had dug up.

“You can put overburden back in the mine at the end,” he said. Overburden is the word used to describe the earth that is stripped off to reveal the resources underneath. (It’s tempting to draw conclusions based on this word—that strip-miners see the landscape and forests only as “burdens.”) In the reclamation process, the overburden, now free of vegetation, can be tossed back in the hole to help patch it up.

“Then you do replanting,” Don continued. “Get the hill made, get it sculpted, build little lakes and marshes.” He described the sequence of plantings that would follow, slowly restoring the land to something like what had been there before. And just like that, as if icing a cake, you could have your environment back.

But Don said he was better as a geologist than as an environmental scientist. So now his job was to build Syncrude’s geological model, based on test data from areas to be mined in the coming years and decades. Bitumen richness, water content, grain size, rock types—there were dozens of measurements. Don integrated it all into a database that would allow the company to decide exactly where to mine, where to set its pits and its benches, where to put the shovels.

“I’m in awe of that,” he said. He was in charge of the mining database of one of Canada’s most profitable companies.

But there was an undercurrent to his enthusiasm. “I’m part of the mining process instead of part of the solution to fix it up afterwards,” he said. “The budget for reclamation is so small compared with the profits they make.” He shook his head. “They should be dishing out more.” And indeed, only a microscopic portion of oil sands land has ever been certified by the government as reclaimed.

The answer, he thought, was stronger environmental regulation. But the Alberta government would never make it happen.

“They’re getting zillions of dollars of royalties,” he said of the province. “If you’ve got land, the government of Alberta will let you go in and take the oil out. They’re interested in profits.”

The late northern dusk had finally descended. The living room was getting dark.

“Do you think you’re raping the planet?” I asked.

Don exhaled. “In terms of pollution, no, we’re not,” he said. “There’s people downstream who say they’re getting cancer from the oil sands operations, but we’re not even putting anything in the water.” But although he didn’t buy claims of carcinogens in the Athabasca River, Don was no climate change skeptic. A huge amount of fuel was being burned to mine oil sands, and to extract and upgrade the bitumen—which meant a huge amount of carbon emissions. And those carbon emissions worried him.

“I once saw a map of CO2 emissions in North America,” he said. “There was a big fuzz up around Fort McMurray. The CO2 from Fort McMurray is probably the same as from all of Los Angeles.”

It seemed impossible. Could Fort McMurray really have carbon emissions similar to those of a city literally a hundred times its size?

Don had a way of saying things I might expect from an environmental activist—yet he was a man who spent his days helping the pit get wider. He embodied, far more than I did, Canada’s contradictory feelings toward the oil sands and the consequences of their extraction.

But we all share in the paradox. Anyone does who both takes part in civilization and cares about the environment. Civilization sustains and protects us as individuals and communities, but it is more than a mere system for shelter and sustenance and order. It is what we are. The unit of the human organism is not the individual but the society. For better or worse, isolated individuals cannot sustain or further the human race. Only in society does it survive.

Today that society is an industrial one, resource-hungry and planet-spanning, growing so inefficiently large, we believe, that it is disrupting its own host. It is not strange, then, that some individuals of that society should question its integrity. They wonder whether the very thing that allows them to exist—the thing that they are—is not somehow rotten at its core.

This is the love-hate relationship in which we are all now engaged, and it is the basis for the entire spectrum of our individual decisions as they relate to the environment. Whether we’re talking about recycling, or voting, or consumer choices, or political agitation, or radical efforts to live off the grid, these are all attempts to square the circle, to mitigate—or, more often, to atone for—our individual role in the disquietingly unsustainable system that keeps us alive. It’s not just about living sustainably. It’s about being able to live with ourselves.

As for Los Angeles, Don had his numbers wrong. Fort McMurray does not emit the same amount of carbon as LA. It emits twice as much.

With the bus tour such a bust, I turned to finding a scenic overlook. I headed for Crane Lake, a Suncor reclamation site that seemed like a good starting point for some creative sneaking.

The word reclamation gets tossed around a lot in these parts, and not only in Don’s living room. It is an important concept for anyone who doesn’t want to feel too bad about strip-mining. Reclamation requirements use the vague guideline of “equivalent land capability,” which means, according to the Alberta government, that reclaimed land has to be “able to support a range of activities similar to its previous use.”

And that’s the key here—its previous use. What, previously, was the use of an undisturbed boreal forest? What if its main use was to remain undisturbed?

I drove. I was in my little rental car, underneath a thick sunshine that was pushing back the afternoon’s storm clouds. The highway was slick with rain and heavy with traffic. It was the beginning of the evening shift change. Work in the mines is divided into two shifts per day, and every twelve hours fresh battalions of truck drivers, shovel operators, plant workers, and engineers come hurtling up Highway 63. The road is long and straight, and the waves of pickup trucks and red and white buses had worked up to an insistent, humming speed. It was at that moment—as I approached the turnoff for Crane Lake, followed by a speeding phalanx of cars and buses—that I saw the ducks.

They came waddling onto the highway from the right shoulder, from the direction of Crane Lake. A mother and six ducklings.

A black sports car had just zipped past me and slotted back into the right lane. I was certain it was going to tear right through them, leaving them in twisted pieces; and that I, unable to stop, would mow through the survivors; and that if by a miracle there were still survivors after that, they would surely be obliterated by the wall of chartered coaches breathing down my neck. After so much talk of ducks and duck deterrents, of duck death and duck lawsuits, I was now about to help write the next chapter of Syncrude’s environmental record, and that chapter was going to be written in blood, the blood of ducks, here on Highway 63, during the shift change.

It was over in seconds. The driver of the sports car braked and veered left, clearing the ducks by a few feet. Spooked, they turned and waddled back the other way, directly into my path. I found my moral sense neatly congruent, if only for a moment, with the needs of Syncrude PR. I swerved onto the shoulder, also missing the ducks, but spooking them again as I blew by and sending them back into the middle of the highway in disarray.

In the rearview mirror, I saw ducklings turning in every direction as their doom approached at seventy-five miles an hour in the form of a looming passenger bus—possibly driven by a man named Mohammed—riding abreast with a big white pickup truck and followed by more traffic behind. There was no leeway, no room for them to swerve. With horror, I imagined the bus careening into the ditch, rolling onto its side.

And then, somehow—it didn’t happen.

The bus leaned forward, lumbering to its knee as it slowed. The pickup truck made a languid weave halfway out of its lane. And the rest of the oncoming column seized up and stopped. As the scene dwindled in my mirror, I saw the mechanized army of the Syncrude evening shift pause, like Godzilla offering Bambi a bouquet of daisies. And there they waited, patiently, as the ducks reformed their little rank and waddled off the highway back into the woods.

Crane Lake is a nice spot, enclosed by a belt of young forest, with reeds clustering along its swampy shores and a nature trail running a mile circuit around the lake, through tall grass and wildflowers. The only footnote to the idyll is that the entire place stinks of oil sand, the same heady aroma that you would smell at a restaurant if the waiter set a bowl of bubbling tar on your table. The trick to experiencing Crane Lake, then, is to appreciate this smell as part of the environment, to remember that it’s coming off of oil sand that God himself put in the ground—even if it’s humankind that decided to rip it open and expose it to the air. As for the constant, popping reports of nearby bird-deterrent cannons, if they weren’t enough to bother the birds that had come to take the waters at Crane Lake, then why should they bother me?

Forget that Crane Lake is called Crane Lake, though. It should be called Duck Lake—or maybe something punchier, like Suncor Ducktasia Lake. It is nothing less than Suncor’s duck showcase. No nature area has ever been so completely tricked out with signs calling attention to what a lovely little nature area it is. There are duck blinds, and a duck-identification chart from an organization called Ducks Unlimited, and a good number of actual ducks present on the lake, possibly including several I had recently failed to murder.

So ducktastic was it that I began to wonder whether Suncor was trying to stick it to poor old Syncrude, with all its duck problems, just up the road. Surely some Suncor PR rep had hoped for a newspaper headline proclaiming, “Suncor, Neighbor to Duck-Destroyer Syncrude, Offers Clean Water, Reeds, at Waterfowl Haven.”

I set out on my hike, keeping the lake on my right, ambling through a spray of purple wildflowers. There were dragonflies, again, and mosquitoes, too—snarling, clannish mosquitoes of the Albertan variety, with thick forearms and tribal tattoos. But I was ready. Don had lent me a bug jacket—a nylon shirt with a small tent for your head and face—and I had armed myself with enough spray-on DEET to poison a whole village. That is to say, I was happy, and ready to bypass all this man-made nature and find my scenic mine-overlook.

Making my way over a small wooden footbridge that spanned a swampy inlet, I was steered southward along the east shore of the lake by a thick forest of young trees on the left. A wooden bench, with grass growing up between the boards of its seat, faced the water. Silence reigned, except for the gentle rustle of the breeze and the constant sound of cannons. I had the place to myself.

But the farther I went down the path, the more the Crane Lake experience started to chafe. All this had been put here on purpose—sculpted, as Don had said. It was too neat. Too self-contained. Halfway down the east side of the lake, I turned to face the dense thicket of young trees that hemmed in the path. From a conspiracy-theory point of view, I reasoned, the very impenetrability of the forest here made it all the more likely that there was something interesting on the other side, perhaps something spectacular, or even hellish.

Ten seconds in, I had lost sight of the lake and the path, crashing through the trees, pushing branches out of the way, plowing through thick spiderwebs that collected on my face-tent. After a few more minutes of bushwhacking, I began to doubt that this was such a good idea. Everywhere I looked, the world looked the same: crowded stands of tall young trees closing in. I wasn’t even sure which direction I had come from. I concentrated on the fantasy of breaking through the trees at the top of a magnificent cliff, looking out over the mine, trucks rumbling to and fro.

I saw light in the distance, through the trees, and went toward it, crossing a small clearing, then plunging back into thick overgrowth and more trees. I jumped a small ditch or stream, heading toward what seemed like a large, open area. It was close. I climbed a small rise of high ground, and it gave way like mud, my foot sinking down into it. I hopped forward, pulling my foot out, and saw sky ahead. Readying a mental fanfare, I broke through the tree line.

There was no vista. No overlook. No oil sands. Instead, I found myself standing on the edge of a cozy little wetland, swampy water winking in the sun.

Crap!

The way was utterly blocked by this revolting picture of nature in repose. I turned back in disgust. It was the sinister hand of Suncor at work, several moves ahead of me, drawing me in with the siren song of bird-deterrent cannons—and the drone of distant machinery, if I wasn’t imagining it—only to throw wetlands in my path.

And now I was lost. Half-blind and overheating inside the face-tent, I walked in what I hoped was the direction of the lake, branches tearing at me. The mosquitoes circled, cracking their knuckles and waiting for that moment when the human, undone by panic and claustrophobia, tears off his bug jacket.

Finally, I saw the muddy rise I had sunk my foot into on the way over—a single landmark in a leafy wasteland—and staggered back toward it. About to cross over it again, I stopped short.

I could see my footprint from before, right in the center of the mound. It was swarming and alive. The small ridge was actually a great anthill. I bent over and looked into my footprint. Ants poured through it in chaos, frenetic in their attention to the fat, wriggling grubs, tumbling over them, picking them up, extricating them from the crater, the giant breach in their city wall. Sorry, guys.

Crane Lake was pleasant in its way, but it was the merest green speck on a huge landscape of unreclaimed and active mine sites. Nor was it even a true test case. I later talked to Mike Hudema, of Greenpeace Canada, and he scoffed at the very notion of reclamation.

“When we destroy an area, we can’t put it back,” he told me over the phone. “We don’t know how to do it. We can create something…but it’s not what was there. It’s not the same, and the way that life in the area reacts to it is also not the same.”

That a guy from Greenpeace would be skeptical of mine reclamation was no surprise. More interesting was his contention that Crane Lake was never a mine site in the first place.

“It’s basically reclaiming the area where they piled the dirt,” Hudema said. “So it’s not actually reclaiming a mine site. It’s not reclaiming a tailings lake.”

Hudema was that rare person who had been camping in the oil sands mines. One sunny autumn day, not long after my visit, Hudema and several of his colleagues had gone for a walk through Albian Sands, an oil sands mine owned by Shell.

Of course, no group of Greenpeace activists can go strolling through a mine without chaining themselves to something. In this case, they attached themselves to an excavator and a pair of sand haulers and rolled out a large banner reading TAR SANDS—CLIMATE CRIME. The entire mine was shut down for the better part of a shift, and Hudema and company spent thirty-some hours camping out on the machinery before agreeing to leave. (Later Greenpeace oil sands protesters met with arrests and prosecution.) The protesters’ purpose—what other could there be—was to make the news, to raise awareness, to convince the world that there was something at stake worth getting arrested for. In them, Canada’s love-hate relationship with the oil sands had most fully flowered into hatred.

But I also think of them as a breed of adventure travelers, and I thought Hudema might be able to share some tips for future visitors to Fort McMurray. Should hikers pack their bolt cutters?

“Well, unfortunately that’s the part I can’t talk about at all,” he said. “It’s sort of a general rule at Greenpeace that we never talk about how we get onto premises, because the question of why we go is much more important.”

What a disappointment. I had expected pointers, even war stories. Weren’t we colleagues of a sort? Didn’t we share a profound fascination with the destroyed landscape of the oil sands mines—even though his fascination was politically engaged and mine was mainly witless?

Think, I thought. Think of some question that will really capture his experience inside the mine.

“What did you eat?”

“We brought all our own food in with us,” he said, “and so we ate a variety of different things.”

A variety of different things? It seemed like an evasion. I closed in for the kill.

“Does that mean sandwiches?” I asked.

“I don’t really want to comment in terms of exactly what we ate,” he said.

Although he refused to talk about access, or sandwiches, Hudema was willing to give me his impressions of the mine itself. “A barren moonscape,” he said. “There is nothing but death. There’s nothing living. All of the trees, all of the brush, everything above the earth’s surface has simply been pushed away. All of the rivers have been diverted, all the wetlands completely drained. You just have these machines, larger than any on the planet, that just carve into the earth, three hundred and sixty-five days a year, twenty-four hours a day. And so from a visceral point of view, it’s a horrific experience.”

“Was there a sense in which you found it perversely beautiful?” I asked.

“Um, no,” he said. “I would never use that word to describe it. It’s just a place that is devoid of all life. A barren, barren moonscape. And you’re constantly reminded of what used to be there. Or what should still be there.”

What should still be there. That was the crux of it, I thought. The beauty or ugliness of a place didn’t have that much to do with what it looked like. Even a moonscape could be beautiful—if it were on the moon. And who would deny the beauty of a desert, no matter how barren or harsh? Beauty depends on what we think is right. How else could we have come to think that unnatural objects like cities or farms or open roads were beautiful? That’s what I wanted to see. The rind of beauty that must exist in every uncared-for corner of the world.

Elevation. That’s what you need. I hired a plane.

We took off straight into the sun, riding a little four-seat Cessna, and arced north, bringing downtown Fort McMurray under our right wing, and then its suburbs, newly carved out of the forest—Don and Amy’s neighborhood. A clean boundary defined the edge of development, beyond which evergreen trees and muskeg swamp stretched out to the sky.

Terris was my pilot. Boyish and friendly, with broad, angular features and a strong Canadian accent, he had been in Fort McMurray for only a few months and earned his living by giving flying lessons and the occasional tour. During the boom of the previous decade, he had flown charters out of Edmonton. It had all been oil business, he told me, carrying executives and engineers up to private airstrips that the oil companies maintained on their lands. “The runways at Firebag and Albian are nicer than the Fort McMurray airport,” he said. Engineers would come from as far away as Toronto and stay for a two-week shift before flying home to take a week or two off duty. It is a common cycle in Fort McMurray, except that most workers do it by car, driving back and forth to Edmonton along Highway 63.

Oil prices had fallen with the recession, though, and the oil sands business had entered another of its cyclical downturns. Terris’s corporate work had dried up.

“So now I’m back in the bush,” he said.

Fort McMurray dwindled behind us. The sun was low, behind a curtain of haze, the earth dusky. Sliding toward us were the sulfur pyramids of Syncrude, their full dimensions even more impressive from the air, a footprint five city blocks to a side.

“I have one flying student who’s a Suncor engineer,” came Terris’s voice over the headset. “He was complaining about how people give the oil sand companies a hard time about polluting the Clearwater River. He said, ‘The Clearwater River is one of the most naturally polluted rivers around.’” Terris was smiling. “The guy said, ‘It’s been leeching bitumen into the water for three million years. We’re just doing the same thing!’”

We all have our ways of feeling like part of the natural order, I guess.

I could now see a low mountain of dry tailings that Don had told me to look out for, a huge heap of sandy mine waste that, like everything else around here, was one of the largest man-made objects in the world. It was so large that it was hard to tell where the tailings ended and the non-tailings landscape began. Beside it was a graphite-colored tailings pond, a mile and a half long, with a single boat floating motionless on its surface.

“People have really different reactions to seeing the mines,” Terris said. “One group I had said it was the most horrible thing they had ever seen. And then you’ll get engineers up here, and they just say it looks like a mine.”

As we considered circling back for another look, the radio crackled to life.

Private aircraft, maintain minimum distance and altitude from Syncrude plant operation.

It was Syncrude security. The company had its own aircraft control. Terris grimaced. “I was hoping nobody would be home.” But it didn’t matter. Already we could see Suncor.

It loomed in the distance. Rather, it did the thing that is like looming but is actually its opposite. It did the thing the Grand Canyon does when you first catch sight of it from the window of a passenger jet. It’s not like a mountain, or a mountain range. Even the Rockies only modulate the landscape—they don’t interrupt it.

Now we saw that interruption, where the flat of the world fell away from the horizon. Where a crater had been punched through the face of the earth.

Terris swung us toward it. He circled, he rolled to one side, and we looked straight down onto the mine, onto its dozens of tiny yellow dump trucks. They drove along a curving network of dirt roads, through a mosaic of craters. Here they sped back to the hoppers, fully loaded and surprisingly fast, kicking up trails of dirt and dust. There, in the intimate cataclysm of a smaller pit, they waited in a group of two or three for their turn to approach a shovel, workers to their queen. And then away again, urgently, to deliver the next load.

The window pressed against my forehead. To the east and the south, I saw forest. But to the north, there was only the mine.

I wasn’t horrified. But I had a funny feeling. Some kind of problem with scale. The trucks and the shovels looked so tiny—such toys and yet so huge. I had spent all week thinking about bigness, about weight, running through the synonyms for huge, and running through them again. The biggest machines in the world, they towered over a person with such magnitude and force. Now they were earnest beetles in a sandbox, themselves dwarfed by the vast footprint they were hollowing out.

“They look like ants!” Terris was shouting over the headset.

But they did not look like ants. They were too big to be ants. And somehow their very failure to be mere specks made them grow ever larger, and part of this growing was how much they seemed to shrink.

Vertigo rushed into the eye that tried to see it. And with the horizon circling around us, I knew that the mine itself, the panorama-swallowing mine, was barely a pinprick on the spinning body of the globe, and the globe itself a mote in the void, and the void itself a mote in another void, and I sat with my head pressed against the window—and felt, just a little, like puking.