CHAPTER SIX

‘Hardly Any Left of the Poor Old 7th Battalion’:

Initiation at Gallipoli

APRIL-MAY 1915

WHEN ELLIOTT AND his men received orders to leave Egypt they were not notified of their ultimate destination. They had still learned nothing definite about the whereabouts of the 3rd Brigade, which had left over a month earlier. The rumour mill, however, was in full swing. No-one in the 7th Battalion was surprised when confirmation came that it was to join the 3rd Brigade at the island of Lemnos prior to participating in a forced landing at the Dardanelles.

It would do so under reshuffled leaders. The internal structure of AIF battalions had been overhauled to conform to the system adopted in the British army. The eight companies of Elliott’s battalion were transformed into four ‘double companies’ comprising four platoons each. Elliott preserved the territorial basis of the battalion by combining what were formerly A and B Companies in the new A Company, the previous C and D Companies in the new B Company, and so on. Further changes became necessary when McNicoll was transferred, having been chosen to replace the ailing commander of the 6th Battalion. Elliott chose Blezard to succeed McNicoll as the 7th’s second-in-command. The company commanders became Mason, Rupert Henderson, Jackson, and McCrae. Elliott had a profound regard for McCrae, who had a charming, amiable, and upright personality; his only shortcoming as an officer, in his colonel’s opinion, was his reluctance to engage in the vigorous chastising that came so naturally to Pompey.

In fact Elliott was very satisfied with the officers he had selected eight months earlier: ‘All the officers have turned out very well indeed’, he wrote. ‘I would not change any of them in spite of the fact that I still rough them up occasionally’. At one stage his misgivings about Birdie Heron led to a stern reprimand for excessive drinking shortly after their arrival in Egypt, but Heron’s conduct was no longer causing concern. And Elliott’s threat to send Denehy home when momentarily displeased with him at Ismailia did not reflect the colonel’s real appreciation of a capable, conscientious, and considerate officer. Elliott was delighted with the continued development of officers who had served under him in the militia, notably Johnston, Layh, and the Henderson brothers. He was also impressed with those less familiar to him before the war. Blick, the shortish lieutenant from Footscray, had been ‘splendid’. So had Blezard. And they had all mixed in well — McKenna, for example, had become McCrae’s closest friend. Elliott felt they were ‘all such good pals that the loss of one will create a terrible blank for those that are left’.

This melancholy observation was triggered by Elliott’s perception of the task the AIF had been given. His battalion would be participating in an enterprise fraught with difficulty — a forced landing from the sea at a fortified coastline manned by enemy soldiers who would be defending their homeland and expecting an imminent attack. British and French forces were to undertake concurrent landings elsewhere on the Gallipoli Peninsula. The objective was to overcome Turkish resistance on the peninsula, allowing the fleet unimpeded passage through the Dardanelles to Constantinople, with the ultimate aim of knocking Turkey out of the war. The invading forces would be assisted by British and French ships, which had attempted unsuccessfully to silence the forts guarding the Dardanelles, initially by sporadic bombardment and then by a full-scale onslaught on 18 March. These purely naval assaults only alerted the enemy; the likelihood of another attempt by a combined naval and military force gave the Turks — and the Germans providing them with crucial guidance — time to prepare. There was now little scope for surprise, an asset of vital importance in any attack and especially crucial in a forced landing of this kind. Before the 7th Battalion even left Egypt, one of Pompey Elliott’s men, having a haircut in Cairo, was assured by his barber that the AIF would be going to the Dardanelles and would never succeed there.

The AIF was ill-served by the complacency and incompetent planning of the British strategists who conceived the Gallipoli venture. It is true that they were constrained by their obligations to the principal theatre of conflict, the Western Front. The clashes there between massive armies had produced not the short war that had been widely predicted but a stalemate, as both sides dug themselves into trenches snaking across France and Belgium. Attempts to break the deadlock had resulted in appalling casualties for the attackers. But even allowing for their inability to devote maximum resources to the Dardanelles, Winston Churchill, Kitchener, and their War Cabinet colleagues were culpably inept in their deliberations about Gallipoli. Their judgment was faulty, their reasoning unsound and at times contradictory, and they arrogantly underestimated the Turks’ fighting capacity. Less than a decade earlier an official appraisal of a notional British offensive at the Dardanelles had concluded that any such attack was doomed to fail; but this sober report was ignored as the Gallipoli concept generated a momentum all its own.

To make matters worse, the complex operation was prepared with extraordinary haste. After the gamble was authorised and General Hamilton was appointed to command it, he had to find his staff from officers not engaged at the Western Front, and he had to be on his way to the Dardanelles within 24 hours. He and his hastily assembled staff then had to formulate detailed plans for the assault and overcome a multitude of daunting tactical, logistical, and administrative problems, all in a few weeks. Inevitably, the organisation was inadequate. One English columnist wrote that Hamilton would have often made more extensive preparations for a recreational shooting trip than he was able to make for the Dardanelles. When Britain and its allies launched a comparable landing against the Germans during the Second World War they took over a year to plan it.

The AIF’s pre-eminent organiser, Brudenell White, was startled by his superiors’ overconfidence and complacency. General Walker, Birdwood’s chief staff officer, was so appalled by the proposed landing that he wanted to make a strong protest — apparently to the Australian government directly — in order to have the whole operation cancelled. However, Birdwood and Bridges felt differently, and their optimism prevailed. Elliott certainly had no illusions. ‘There is no disguising the fact that the enterprise contemplated may turn out to be exceedingly dangerous’, he admitted on 22 April.

Elliott and other battalion commanders, dressed like sailors, had scrutinised possible landing sites during reconnaissance cruises aboard British battleships. On their initial inspection they were conveyed by the Queen Elizabeth, then the most powerful ship afloat. In a brief address General Hamilton informed the assembled commanders that they were about to attempt a feat that had not been accomplished since William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066; if they succeeded, their achievement would be even greater than Wolfe’s victory at Quebec in 1759. ‘It was a wonderfully interesting trip’, enthused Elliott. ‘During the observation we were shelled by the enemy’, but fortunately the ‘closest shot was a full 400 yards away’. Intelligence reports based on aerial reconnaissance revealed that the enemy was busily fortifying the peninsula. Developments at the Western Front had confirmed that determined defenders able to utilise artillery, barbed wire, and machine-guns could make things very difficult for an attacking force. Clearly, Elliott and his battalion had an awesome challenge ahead of them.

Like many of his men, Elliott found his thoughts turning to home and loved ones with growing intensity. ‘I want to come back and see you and my darling bairnies oh so much’, he assured Kate, yet his commitment to his command responsibilities was unwavering; besides, ‘I would love to do something great in the war’. How were these aspirations to be reconciled?

I want you to pray good and hard for me that on the day of trial I may shut out of my mind all thought of you and of my sweet ones and remember only my country and my duty. It will be hard for you to ask this my loved one but it is only by such sacrifices that our country can survive, and it would be better that you lose me and we win the war than that we should lose the war and you keep me. It is very very hard my love even to contemplate the thought of never seeing you again yet we both must pray that when the time comes I shall have no thought of self.

Elliott’s characteristic openness was consolidated by the no-secrets pact he and Kate had agreed to maintain in their wartime communications. Kate sometimes felt that her correspondence lacked content, but Harold treasured every snippet: ‘I read your letters over and over again for fear I miss a word of them’. News from home was precious, and it was wonderful ‘when you are far away to think that someone loves you so truly and well and is watching and waiting for news of you’.

However, with the Gallipoli venture about to be launched, unsettling news from home rocked him. A bombshell from Belle informed him that Kate was in hospital recovering from an operation; Belle had taken three months’ leave from work to look after the children during Kate’s recuperation. Understandably perturbed, he wrote home anxiously, wondering what the operation was for (apparently some problem affecting her teeth), but soon had to put it out of his mind. The landing, having been postponed for two days because of bad weather, was to take place at dawn on Sunday 25 April. Elliott left Lemnos on Saturday morning aboard the Galeka. With him was his battalion (less Mason’s A Company, which was travelling on the Clan Macgillivray) and the 6th Battalion under McNicoll.

Sleep was elusive on that last night before their appointment with destiny. The stakes, as well as the perils, everyone sensed, were substantial; exhilaration vied with nervousness as the dominant emotion. There was one universal preoccupation: how would they acquit themselves in the great test that was rapidly approaching? For most, it was the experience of being under fire for the first time, and how they would react to it, that was monopolising their thoughts. At least Elliott knew what it was like to be a target for real ammunition, but he was well aware that leading an infantry battalion into action in an operation of this magnitude and complexity — there had been no bigger amphibious assault in the entire history of warfare — would be a challenge. His misgivings about the enterprise only strengthened his resolve to do everything in his power to make his battalion’s contribution as successful as possible.

Surveying his men with a fatherly eye as they quietly prepared themselves, he felt proudly confident they would do well. However, like many others, he could not help wondering about casualties, and whether he would become one himself. Elliott’s friend Major Bennett was similarly reflective as he mingled with the 6th Battalion on the Galeka:

Moving among them, one could see a look of determination in every man’s face. They were very silent. Many were the prayers offered that night. All were anxious as to how they would behave under fire on the morrow … They knew that the reputation of Australia was in their hands … They knew of the great difficulty of their task and they knew that the operation was extremely hazardous. They knew, too, that casualties would be heavy. It was a solemn voyage.

Most of them were thinking of home; some were imagining their family’s reaction if the next day proved their last. Many Australian soldiers wrote to loved ones that night. A 7th Battalion officer, Alan Henderson, penned a letter to his parents:

At last we make our final move and very soon we will have started to do what we came away for and have waited so long to do. While you are in church tomorrow thinking of us, we may be needing all your prayers … but everything is ready and everyone quietly confident of success. It is going to be Australia’s chance and she makes a tradition out of this that she must always look back on. God grant it will be a great one. The importance of this alone seems stupendous to Australia while the effect of success on the war itself will be even greater.

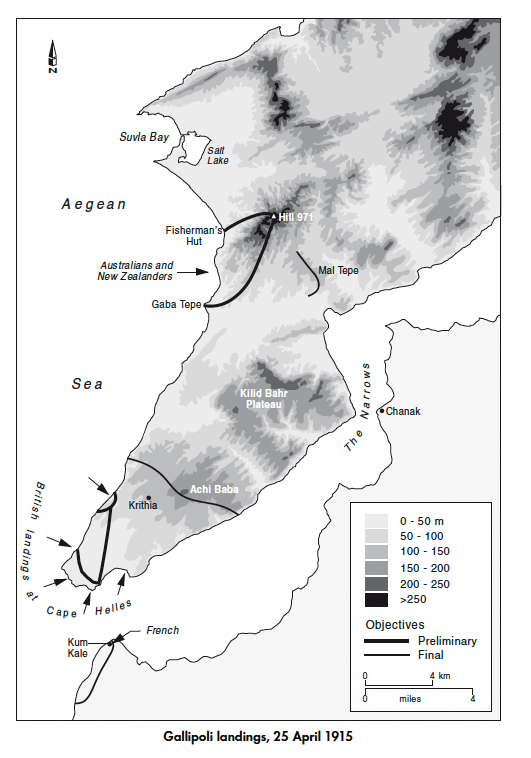

The landing was to be undertaken initially by the 3rd AIF Brigade, with the 2nd Brigade to follow. These units were to be later reinforced by the 1st and 4th AIF Brigades and a brigade of New Zealand infantry. The landing was to take place near a prominent promontory called Gaba Tepe, which jutted into the sea on the western side of the Gallipoli Peninsula. Gaba Tepe itself was strongly guarded by barbed wire and machine-guns, and an artillery battery was known to be located nearby, but there was no wire at the chosen landing site a mile to the north. The landing force was supposed to take control of the ridge rising from Gaba Tepe to the commanding height over four miles away known as Hill 971 (almost 1,000 feet above sea level), together with the extensive area of precipitous slopes and ravines situated between this ridge and the coast. The terrain was so extraordinarily rugged that it would have been a tall order in peacetime, but the attackers also had to contend with a tenacious enemy already alerted by the naval assaults to expect an imminent invasion; the Turks did not know, however, where the landing(s) would be attempted.

The task allotted to the battalions of the 2nd AIF Brigade was to establish themselves on the left of the 3rd Brigade, extending the area seized in a northerly direction and capturing the vital high ground at and around Hill 971. Elliott’s 7th Battalion was to be responsible for the left flank. If everything went according to plan, this would extend from the approach to 971 back to the beach near a point known as Fisherman’s Hut, over two miles away (the capture and retention of 971 itself was the 5th Battalion’s assignment). The 2nd Brigade was to be conveyed from its transports to shore in a number of ‘tows’, which consisted of a small steam pinnace towing three connected rowing-boats containing between 40 and 50 soldiers each. When the battalions of the 2nd Brigade landed, they would be guided to a particular rendezvous by staff officers, who would choose the most suitable location in the prevailing circumstances.

In the early hours of 25 April 1915 the Galeka quietly made its way towards Gallipoli in total darkness. The moon set shortly before three o’clock, leaving only the stars to dilute ever so faintly the enveloping blackness. The three companies of Elliott’s battalion (who were to depart from the Galeka first, followed by the men of the 6th) had already had a hot breakfast of stew and tea. They were lined up on deck, their equipment checked, ready to disembark. Sharp stabs of apprehension surged from tightly knotted stomachs. Visibility was minimal, but all eyes were fixed on the distant, just-discernible coastline. They could not see the tows ferrying the first wave of the landing force, but knew their 3rd Brigade comrades were silently approaching the beach. The strain was immense as they waited and waited, wondering when the landing force would be detected and how vigorously it would be opposed — factors which would, of course, crucially influence their own fortunes when their turn came.

At last, just before 4.30am, the yellow flare of a beacon suddenly penetrated the darkness, and the crackling sound of shooting —initially sporadic, then continuous — became clearly audible. For another quarter of an hour, as the night sky began to pale with the approach of dawn, the Galeka steamed towards the coast, reaching its designated position punctually at 4.45. But there was no sign of the tows supposed to be meeting the Galeka to convey its men to the shore. The captain of the Galeka reacted boldly, moving his ship 600 yards closer to the beach, but the tows that should have arrived after depositing their quota of the 3rd Brigade ashore still failed to appear.

An artillery battery at Gaba Tepe now took aim at the Galeka. Menacing projectiles roared towards Elliott and his men with a fearsome screech, burst with a sudden thunderclap and dispersed their lethal shrapnel ominously close. This salvo, a novel experience for nearly everyone aboard, prompted plenty of deep breaths and surreptitious wiping of clammy hands on thighs.

Colonel Elliott joined other senior officers at a hastily convened conference. The naval commander, who had ultimate responsibility for the ship and the men, said the shelling was too dangerous to wait any longer for the tows, and the men would have to row themselves ashore immediately in the Galeka’s own lifeboats. Elliott objected. He was well aware that even the most carefully made plans often come unstuck in the chaotic turmoil of battle; he knew that in such situations the ability to react resourcefully and devise feasible alternatives was one of the attributes of a competent commander. But this change to his battalion’s role could have disastrous consequences. The disembarkation arrangements would be thrown into disarray because they had been based on the carrying capacity of the rowing-boats in the tows, and the Galeka’s lifeboats were much smaller. Furthermore, few of the men were used to rowing. They would be more vulnerable on their way to the beach without the protective machine-guns mounted in each of the steam pinnaces. And, crucially, it was the naval personnel in the pinnaces who were to guide them to the appropriate place on the beach. Because of inadequate precision in the planning of the operation, and excessively restricted circulation of vital information about it, all Elliott knew about his battalion’s intended landing position was that it was towards the left of wherever the 3rd Brigade had managed to get ashore. Nevertheless, having made these objections, Elliott deferred to the naval commander. ‘You are in charge’, he acknowledged. ‘If you give me a direct order I will obey it’. The naval commander reiterated that the Galeka was in real danger of being sunk by enemy shelling and the soldiers would have to disembark immediately.

Elliott ordered B Company to get into the lifeboats. Although the advent of dawn was gradually increasing visibility, it was still not clear precisely where the first wave had landed. He was acutely conscious that his instructions, through no fault of his own, were inadequate: ‘All the direction I could give them as to the landing place was to keep to the left of the 3rd Brigade’. Into the first boat clambered B Company’s commander, Major Jackson, and about 35 men. Three more boatloads soon followed. These four boats headed off close together, containing most of the initial D Company men from Essendon. Observing them intently, Elliott noticed Captain Layh perched awkwardly. ‘Keep your bum down Bertie’, he called out. The remainder of B Company accompanied Lieutenant Swift into the fifth boat. Elliott decided it was now time for him to go, and he climbed into the sixth boat with Lieutenant Grills and the first portion of C Company.

Being towed in by steam pinnace, as arranged in the operation plan, would have required the men to row only the last fraction of the distance from ship to shore after being released from the pinnace. Rowing all the way in, under fire, was a very different proposition: although the Galeka’s captain had brought his ship closer to the shore than any other transport, the beach was still some 1,200 yards away. But everyone was keyed up, and the oars were wielded to good effect. When the fifth and sixth Galeka boats were 400 yards from the beach, a pinnace materialised at last and towed them the rest of the way.

The closer they came to the shore, the louder the noise of gunfire grew. A shot from a Turkish rifle resembled the sharp crack of a cricket ball hit powerfully by a bat; machine-gun fire ‘was an altogether more intense sound, like pneumatic riveters on a boiler plate’. Intermittently obliterating all other noise was the crescendo of shellfire. Shrapnel shells were rocketing from Gaba Tepe towards the defenceless boats with an unnerving shriek — like the roar of several trains hurtling through a tunnel together at top speed — before exploding with a loud bang and scattering their deadly contents, which spattered into the water or thudded into Australian flesh. British warships retaliated with a thunderous bombardment of powerful high-explosive shells. Although no-one in Elliott’s boat was caught by shrapnel, the near-misses led to quickened pulses and churned stomachs. Elliott did what he could to steady the men with him, and puzzled about the irreconcilable difference between the looming cliffs in front of them and the less forbidding coastline they were supposed to be approaching.

As they neared the shore the men became anxious to get out of the boats as soon as possible. There was a discernible bank on the far side of the narrow beach; after feeling vulnerable and unable to retaliate for what seemed like ages, they were keen to get themselves ashore and utilise whatever cover the beach afforded. They were weighed down by waterlogged clothing and equipment, slippery stones gave them an awkward underwater footing, and some were disconcerted by the dead bodies and blood-red tinge in the water; but they were all desperate to escape the menacing fire aimed at them. (In other boats some were too eager: underestimating the water depth and encumbered by their heavy equipment, they drowned.) A few minutes’ strenuous wading brought them ashore, and Elliott, Grills, and Swift shepherded their group towards some temporary cover. Elliott told them to wait there while he ascertained where they were to go next. It was now almost 5.30am.

Ahead of them was supposed to be an open plain which they were to cross before climbing a low hill. Instead they found themselves confronted by utterly different country — rugged ridges and ravines covered by obstructive, waist-high undergrowth. From the little stony cove where they had landed, the most prominent feature was an exceedingly steep hill some 300 feet high rising directly above them. Elliott realised that the AIF had been put ashore at the wrong place. (The traditional explanation of an unexpectedly strong current has been increasingly discredited. It is more probable that the mistake occurred simply because — as Elliott concluded at the time — naval personnel could not distinguish the coast clearly enough in the darkness.)

The orders for the landing had specified that after reaching the beach the battalions of the 2nd Brigade would be guided forward by one of two designated staff officers. Elliott went looking for them. He was told that neither had landed. McCay had not yet arrived either; Elliott was in fact the first senior officer of the 2nd Brigade ashore. He then asked for the whereabouts of the 3rd Brigade’s Scottish-born commander, Colonel E.G. Sinclair-Maclagan, an experienced and capable leader. Told that Sinclair-Maclagan had established his headquarters near the top of the precipitous hill towering over the landing site, Elliott hurried away in that direction.

As his powerful frame scrambled up the incline, retracing the footsteps of the 3rd Brigade first wave who had charged straight up in the dark, he experienced the same difficulties with the terrain as they had. Besides having to contend with the slope itself — steep enough to be challenging for anyone — he found that the tangled, prickly scrub was sometimes too dense to penetrate and forced frequent changes of direction. The rough, gravelly soil made it hard to keep a foothold. Whenever he lost his balance and clutched around for support, a wrong choice could have painful consequences — barbed bushes ripped through clothing and scarred the skin underneath. Plenty of bullets were flying about, but at least the trench at the top of the hill was no longer occupied by the Turks who had been shooting down from there when the AIF began climbing up towards them.

During Elliott’s ascent the wounded Australians passing him on their way back to the beach indicated the fierceness of the fighting up ahead, and the piteous cries he heard from dying soldiers were heart-rending. But the little that could be done for those poor souls was a task for others, and he had steeled himself not to allow such distractions to affect his main task — ensuring the correct decisions and actions were taken to enable the 7th Battalion to play its part as effectively as possible. Moreover, at this early stage any avoidable delays in sending AIF units where they were most needed could affect the outcome of the battle. So he pressed on determinedly until he found Sinclair-Maclagan. By the time he did, after a quarter of an hour’s arduous climbing, his cheeks were red and he was puffing hard.

His conversation with the brigadier was brief. Sinclair-Maclagan, as the most senior commander ashore, was endeavouring to retain control of an operation that had gone so astray he had already decided, on his own initiative, to amend it drastically. He had in fact been pessimistic about it all along. During a reconnaissance cruise on 14 April he had observed that if the coast was ‘strongly held with guns’ it would be ‘almost impregnable’, and before leaving Lemnos he told General Bridges that ‘if we find the Turks holding these ridges in any strength I honestly don’t think you’ll ever see the 3rd Brigade again’. Now, to Elliott, he quickly confirmed that the AIF had been put ashore about a mile north of the intended landing place; because of this, he added, the original plan could not be implemented. Having concluded that the most appropriate course in these circumstances would be for the 2nd Brigade to come in on the right of the 3rd Brigade rather than on its left as planned, he ordered Elliott to collect his men on the right of the AIF’s position. Elliott returned to the beach as quickly as he could. Both the operation plan and Elliott’s preparatory visualisation about how his role might unfold had been based upon the assumption that his battalion would have responsibility for the extreme left; yet within minutes of his arrival ashore he had been directed to place it on the far right.

Arriving back at the beach, he relocated the fifth and sixth Galeka boatloads under Swift and Grills. He panted up to them, told them to proceed to the southern end of the cove in accordance with Sinclair-Maclagan’s instructions, and began looking for other 7th platoons to send there also. Before long he had collected D Company and part of C Company, but was unable to find the rest of C Company, his machine-gun section or any of Jackson’s B Company who had filled the first four Galeka boatloads. He discovered that A Company had landed from the Clan Macgillivray and been directed to a relatively protected forming-up area about 400 yards inland. Elliott then sent all the 7th men he had assembled on the beach to this spot, which became known as the Rendezvous. From there some of them were immediately ordered forward to the fighting taking place on the 400 Plateau, a prominent feature adjoining and overlooking the Rendezvous.

Elliott was busy reorganising the 7th men at the Rendezvous when McCay arrived. The brigadier told him that because the 5th Battalion had been delayed the 7th would have to take over its task of capturing the all-important Hill 971 almost three miles away. Elliott concluded that Sinclair-Maclagan’s switch of the 7th to the south had been a temporary manoeuvre to shore up the right flank until other units became available, and its ultimate role was still on the left as originally planned. He accordingly ordered all 7th platoons left at the Rendezvous to follow the portion of his battalion that had already gone forward to the 400 Plateau, with a view to beginning an advance in a north-easterly direction towards 971. Still puzzled and increasingly concerned about the whereabouts of B Company, half of C Company and his machine-gun section, he positioned himself at the entry to the Rendezvous, where detachments of the 2nd Brigade were continually arriving, and acted as a general directing post while looking anxiously for the missing 7th cohorts. After a while he lifted his gaze to the slope leading up to the plateau where he had sent his battalion, and saw the last company disappearing from view; on the crest, supervising this movement, he recognised the stalwart figure of Captain Hunter. Elliott decided it was time to join them.

He was about to hasten forward when McCay reappeared. Following his brief conversation with Elliott, McCay had chanced upon Sinclair-Maclagan, who told McCay he wanted the whole of the 2nd Brigade inserted on the right of his brigade instead of on its left. McCay was understandably taken aback to discover that the operation, especially his brigade’s part in it, had been so radically altered. Sinclair-Maclagan assured him it was essential, and there was no time to lose; McCay acquiesced grudgingly. It was in order to notify Elliott of this fundamental switch that McCay caught up with him at the Rendezvous. The brigadier said he now wanted the 7th to be inserted into a gap in the AIF front line between two 3rd Brigade battalions on the 400 Plateau. Adjusting quickly to this unexpected change, Elliott sent the necessary messages to his company commanders on the plateau. He subsequently received a message from one of them, Rupert Henderson: ‘Have been ordered to advance 300 yards beyond the position you have assigned to me’. (McCay had given this order to Henderson, Elliott noted afterwards, ‘without reference to me’.) Although Henderson sent further messages back to him, Elliott was having trouble maintaining contact with his other companies on the plateau; his second-in-command, Blezard, had been severely wounded in the chest, picked off by a sniper after waving his men into position.

Sensing that the situation up ahead was fluid and precarious, Elliott felt even more torn between his desire to be with the men he had sent forward and his growing concern about the others he had been unable to find. He still hoped to find traces of them as 2nd Brigade detachments kept arriving at the Rendezvous, and he was reluctant to leave his directing post; but when he received word from Henderson that a large force of Turks was advancing, he decided that he ought to climb up to the plateau and ascertain what was happening there. As before, he took no notice of the enemy projectiles flying around, until a sharp jolt to his right ankle followed by acute discomfort confirmed that this was one bullet he would be unable to ignore. It quickly became clear that he was significantly disabled and unable to carry on.

He felt annoyance and frustration more than anything. To be knocked out of the fighting at a critical time when his men needed his guidance (and without having seen a single Turk) was intensely galling; more excruciating, in fact, than the pain in his foot. He refused to be evacuated immediately. Not until he had arranged for ammunition to be brought forward and for messages confirming his disablement to be sent to McCay and Mason (who, with Blezard wounded and Jackson missing, was now in command of the battalion) did he reluctantly agree to be carried away on a stretcher. After his wound was patched up he was helped down to the beach. He had to lie there for hours.

The haste, complacency, and contempt for Turkish military prowess that had infected preparations for the landing were particularly evident in the arrangements made to care for the wounded. According to a senior AIF medical officer, Colonel Neville Howse VC, the extent of the neglect ‘amounted to criminal negligence’. Some of his colleagues accused the responsible British authorities of ‘murder’. For an operation of this scale the provision of medical facilities was scandalously deficient. There was only one hospital ship, the Gascon; there were nowhere near enough doctors and other medical staff; their supplies, from bandages and dressings to stretchers and surgical instruments, were woefully inadequate; and, when predictable problems ensued, attempts to rectify the shambles were hampered by culpably defective communication links with the top-level medical administrators.

There were inordinate delays. Despite desperate efforts by overwhelmed doctors and orderlies, thousands of wounded soldiers endured monstrously prolonged suffering. Small boats carrying dozens of stricken men — who were wet, hungry, and seasick as well as injured — approached the Galeka and several other transports which had been urgently utilised to take the wounded away from Gallipoli (though they had little or no medical staff or facilities on board), only to learn that each had no room for more. Some men with grievous wounds received no proper treatment for days. Many preventable deaths occurred and numerous avoidable amputations eventually had to be performed. Alan Henderson, the 20-year-old 7th Battalion lieutenant who wrote such a stirring letter on the eve of the landing, died at sea after being placed aboard one of these transports.

Morning became afternoon, and still Harold Elliott lay waiting on the stony beach as the battle raged above and around him. His foot was throbbing and he was uncomfortable in his wet clothes, which had been saturated when he waded ashore and further moistened by the sweat generated by his purposeful exertions during the battle. But he could tell he was in better shape than many others around him. His long wait on the exposed beach ended at last when he was carried aboard the Gascon, which departed for Lemnos at 9.00pm. From there he was transported to Alexandria, arriving on the morning of 29 April. The following day he was admitted to the Australian hospital near Cairo at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel.

Recovery was slow. The wound itself did not heal quickly. It took weeks longer for his foot to regain enough strength for him to get about. He also suffered a severe bout of bronchitis. Triggered, he was convinced, by the hours he had to wait lying in damp clothing after being shot, his illness threatened to develop into pneumonia, and for a while caused the hospital staff acute concern: it ‘really troubled me more than the wound, I think’.

While regaining his strength he had plenty of time for reflection. In pre-war days he had advised would-be officers that if you do everything possible as a commander yet your unit sustains severe casualties, then ‘your conscience at least will be easy, however heavy your heart’. As Elliott reviewed the landing, his heart was heavy indeed, but his conscience was clear. Many a commander could have been bewildered or rattled by the varied instructions Elliott received, but he had responded readily and decisively. His bravery and selflessness set a fine example to his men, increasing their regard for him. Clarrie Wignell, one of the Euroa lads recruited by Lieutenant Tubb, sent a letter home about the landing:

The poor old Colonel got shot in the leg and had to leave, and when they attempted to carry him to the boat he said, ‘No, there are plenty worse than I to go first’. The men love him.

Not all the AIF commanders distinguished themselves. Shortly after General Bridges landed with Brudenell White around 7.30am on 25 April, they were puzzled to find a 3rd Brigade colonel still on the beach with his head pressed into the bank. When they saw his terrified face they understood. Bridges later found McCay similarly unhinged by the stress and turmoil of the battle. According to White, McCay

was completely lost and his grip on things seemed gone. He could not orient himself. Bridges came along with his yard and a half stride and wanted to know what the hell he was doing … As Bridges grew more and more angry I saw McCay’s face change. He began to get a grip on himself and before long he was in complete control.

Courage and capacity in battle can fluctuate. Some soldiers manage to be consistently outstanding, but the performance of others can differ significantly from one engagement to the next or — as with McCay at the landing — can even vary considerably during a battle.

Both Bridges, one rung above McCay in the military hierarchy, and Elliott, one rung below, had similar views about McCay: his intellect commanded respect, but his pedantic argumentativeness could be annoying. At the landing, at a stage when Elliott was closer to the action than McCay, he had suggested that it was time to consider an order to dig in; the brigadier responded that he was running the fight, not Elliott. McCay’s abrasive manner made him unpopular with the rank and file, as did his tendency to assume the worst of them in battle. Soldiers who were keen and brave but not sure exactly where to go — because their platoon commander and senior NCO had been killed, or for other plausible reasons — took understandable umbrage when McCay swore at them, accused them of cowardliness and threatened them with his revolver. Elliott was unenthusiastic about McCay’s performance at the landing:

Brigadier McCay, although he deservedly gained considerable fame as a brave man, was far from being an ideal commander. He had little faith in anyone’s ability save his own and constantly interfered with the arrangements properly belonging to his Battalion commanders … which completely deprived them of any initiative and any responsibility.

Elliott’s misgivings before the landing were vindicated by what occurred on 25 April. Because the terrain was so ‘rugged, broken and trackless’, he concluded afterwards, the area to be seized by the landing force was ‘far too extensive’. He was appalled by the level of casualties his battalion seemed to have sustained, but felt ‘very proud’ of his ‘magnificent’ men who had done ‘wonderfully well’. Elliott was keen to hear the experiences of every member of the 7th he encountered during the ensuing weeks. He had talked with some while waiting on the beach; he also had 80 wounded 7ths with him on the Gascon, while others from his battalion were admitted to hospital at Heliopolis. He was soon able to piece together a reasonably accurate picture of what had happened.

The 7th was not the only AIF battalion to lose its cohesion after landing at such an unexpected place and then complying with emphatic instructions to push forward rapidly. It was not surprising that companies, platoons, and smaller groups became detached and intermingled with other units. Both the missing half of C Company and the machine-gun section, Elliott learned, had climbed the steep hill overlooking the beach (as he did when looking for Sinclair-Maclagan) and involved themselves in the desperate fighting beyond. The officers leading those C Company men (who included McKenna and Conder) were severely wounded; the machine-gunners suffered such heavy casualties that 21-year-old Lance-Corporal Harold Barker found himself in charge (and rose to the occasion superbly). Elliott also heard disturbing reports of casualties in the fighting on 400 Plateau, which he had been about to scrutinise when he was wounded.

What he discovered about the missing men of B Company moved him profoundly. Whereas the fifth and sixth boats (the latter containing Elliott) had been collected by a pinnace and guided to the shore, the first four boatloads had rowed themselves all the way from the Galeka to the beach without any assistance. All they knew about where they were supposed to be going was that they had to aim to the left of wherever the 3rd Brigade had landed. They accordingly headed towards the northern-most flashes of fire they could discern ashore in the emerging dawn. Shrapnel was bursting over other boats away to the south, but their main concern was the volume of rifle and machine-gun fire aimed at them from the shore; they could see the bullets cutting into the water ahead of them. They realised they would be sitting ducks, but they did not hesitate.

Time seemed to stand still while they rowed steadily towards the danger zone. Jackson, Layh, and Heighway were in the leading boat; Ken Walker’s fellow ‘musketeers’ from Essendon, Ellis ‘Teena’ Stones and Bill Elliott, were among the rowers, feeling acutely vulnerable, expecting a bullet in the back at any moment. But at no stage did they waver. Having rowed about three-quarters of a mile since leaving the Galeka, they encountered the gunfire in earnest about 50 yards from the beach. It was a hail of bullets. One by one the rowers were hit, and slumped down. Others immediately seized their oars. Another of the rowers from Essendon, Harold Elliott later wrote,

[a] little red-headed laddie named McArthur, scarcely more than eighteen, was shot through the femoral artery and the blood spurted from his thigh as the water squirted into the boat … A sergeant attempted to bind it up. ‘It’s no use, Sergeant’, he cried, ‘I’m done’, yet he rowed on until he swooned from loss of blood, and a comrade took his place.

Teena Stones was hit by a bullet that rebounded from his oar and scythed its way through the bones and flesh in and around his left knee; he ‘tried to keep rowing but it was no good’. Of the original rowers in the leading boat, only Bill Elliott was not hit. Heighway, at the tiller, was hit through the chest. The impact nearly knocked him into the water. Layh saw him slide into the bottom of the boat, where he began to twitch and kick disconcertingly before he stopped quivering and attempted to operate the tiller with his foot.

At last the boat scraped the shore, and those able to get out lost no time in doing so. In the process more were hit, including Layh (ironically, in view of his colonel’s last words to him, in the left buttock). He managed, however, to scramble across the beach with other survivors, all of them desperate to reach the flimsy sanctuary afforded at this part of the coast by grass-tufted sand hummocks. They tried their utmost to return the enemy’s fire, but the fusillade aimed at them seemed, if anything, to intensify. Alongside Layh (who had collected another wound in the calf) a man was hit three times. In agony, he begged Layh to finish him off; another Turkish bullet made his request redundant. To find out how many from the leading boat were still going, Layh called out to the men around him. Only six answered. Bill Elliott was among the silent. Layh thought he and the rest would soon be history, too, sensing that the Turks in the vicinity were about to come down from their strongpoint and rout his outnumbered remnant. In an attempt to deter these Turks, he ordered his men to make their bayonets visible above the sand hummocks to indicate they were about to charge.

To the great relief of Layh and his comrades, the torrent of enemy fire tormenting them suddenly ceased. They were soon joined by survivors from the other three B Company boatloads. Casualties in these boats had also been severe. About 140 men had left the Galeka in those first four boats, but only around 35 mustered on the beach with Jackson (who had been wounded three times), Layh and Scanlan. They had arrived directly opposite the 7th Battalion’s original objective, almost a mile north of the cove where Colonel Elliott and the rest of the battalion had landed; the withering fire aimed at them had come, in fact, primarily from the direction of Fisherman’s Hut. Jackson hurried away to get help for the wounded. Layh and the others eventually decided to make their way along the beach towards the main AIF position. Variable cover and menacing Turkish fire made this a difficult task; one machine-gun held them up for hours. By the time Layh arrived at the cove it was nightfall, and he had only eighteen of the initial 140 men still with him.

Harold Elliott was particularly stirred by the plight of his wounded men in front of Fisherman’s Hut. The Turks had maintained a concentrated fire on the leading boat, even after it was clear that everyone in it was either dead or gravely wounded. As bullets ripped into the boat — Heighway ‘could smell the burning paint’ — it became so riddled with holes that it began to fill with water, compounding the fear and misery of the men trapped inside. Pinned down by the bodies of their comrades as well as by merciless enemy fire, they became aware that liquid of a gruesome crimson hue was swishing ominously around them. Teena Stones was desperate to staunch the blood pouring from his and others’ wounds, but he had a dying mate lying across him and ‘it was impossible to get him to move’.

They stayed there in this pitiful state for well over an hour before assistance from the hard-pressed medical units to the south materialised. Stretcher-bearers carried Stones ashore, checked the flow of blood from his wound by wedging his camera into the hole where the back of his knee used to be, and transferred him a mile along the beach to the cove where most of the AIF had landed. Like his colonel, he had to lie there for hours. Shrapnel burst intermittently above, inflicting a further wound on the man alongside him. When he was at last taken off the beach, his was one of the batches of unfortunates who were ferried from ship to ship before being placed on a crowded transport for an agonising journey to Alexandria. He then joined his colonel at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel, where amputation of his leg was only narrowly averted.

Like Teena Stones and Alex McArthur, many of the B Company men who suffered terribly in front of Fisherman’s Hut were young Essendon lads who had served under Elliott’s command before the war. Elliott was greatly affected by their ordeal. He often referred to it in subsequent years, sometimes with graphic, lyrical intensity:

The water gained in the boat and flowed around them, its blue turning a ghastly red with the blood of the wounded and dying. Still the hellish hail of fire continued, it did not cease when the boat grounded but swept over them, still piercing the writhing bodies through and through … Oh those leaden minutes of agony, how slowly, how dreadfully they passed by.

‘I wonder’, Elliott reflected, ‘what people in Australia thought of that dreadful slaughter’.

On 28 April the Melbourne Herald published in its final edition a brief official announcement that the AIF had participated in a landing at Gallipoli. Despite fervent yearning in thousands of Australian homes for more detailed news, only the most meagre information filtered through for several days while more and more Australians were notified (prior to soldiers’ names being publicly announced) that their relatives in the AIF had become casualties. The full gravity of the situation swept through Essendon on Saturday 1 May, when the clergymen — who had been given the sombre task of informing soldiers’ next-of-kin that their loved ones had died at the Dardanelles — were busy dealing with the consequences of the fighting in front of Fisherman’s Hut. With rumours circulating wildly, many Essendon families waited in dread to see if they would be approached by these messengers. Among them was the Stones household; Bill Elliott had been boarding with them for some years. Confirmation of his death came in a poignant cable from Teena: ‘Wounded leg Bill gone Ellis’. Many families were similarly grief-stricken in Bendigo, Footscray, and other areas that had given their sons so willingly to the 7th Battalion. With all regions of Australia represented in the landing force, there was anxiety and gloom throughout the nation.

Kate was notified on 30 April by the Defence Department that her husband had been ‘slightly wounded’. Elliott himself arranged for a cable to be sent to his partner Roberts: ‘Walker and I wounded neither seriously advise wife Elliott’. His first letter home was to Kate on 3 May. ‘I hope you are not worrying too much’, he wrote, concerned about her health in the wake of her operation. He then turned to his news:

Well now last Saturday morning before daylight we Australians started to land about halfway along the Gallipoli peninsula … The formation was like Sandringham at home. A narrow strip of beach with high cliffs above rising in successive ridges to 400 feet or more. Such a scramble it was to get to the top and we were weighed down with three days rations and packs. We threw the packs off on the beach and left them. The enemy’s guns a couple of miles south shelled our boats as they approached the beach … Of course, we suffered heavily.

Elliott was far from well when he wrote. The landing actually occurred on a Sunday. He admitted in his next letter he had no idea what he had written in its predecessor.

In Australia the heavy burden of AIF casualties was known several days before any detailed account of the landing was published. It was not until 8 May that a dramatic dispatch by an acclaimed English war correspondent describing the AIF’s landing reached Australians, who reacted with exaltation and relief that their countrymen had displayed such courage and dash in undertaking their difficult task. As they read with pride that there had been ‘no finer feat in this war than this sudden landing in the dark and storming the heights’, emotions already churned up by the casualty lists were further stirred by the realisation that Australia had made a spectacular impression in an international setting.

Events at Gallipoli that same day were guaranteeing that many more homes throughout Victoria would be plunged into misery. The British landings at the southern tip of the peninsula had also resulted in severe casualties and limited progress for the invaders. Reluctant to concede that the foothold established at Helles represented the limit of the British advance there, General Hamilton felt that another thrust towards the village of Krithia was justified before the conflict in this sector stagnated, like the Western Front had, into static warfare from entrenched positions. Together with the New Zealand brigade, a brigade from the AIF Division was to be detached to assist with the assault: Bridges decided on McCay’s 2nd Brigade. In Elliott’s absence his battalion was under the temporary command of Lieutenant-Colonel Gartside, a senior 8th Battalion officer with Boer War experience.

Having been conveyed by trawler to Helles, Pompey’s men had the distinct misfortune to come within the orbit of Major-General A.G. Hunter-Weston, a British divisional commander. It was the performance of commanders like Hunter-Weston that endowed British generals in this war with a notorious collective reputation for blinkered incompetence (monstrously unjust though it was, of course, to many of them). Hunter-Weston was bombastic and gruff, ‘self-important and vain’. Inflexible and reckless, he had an obscenely cheery indifference to the casualties his men endured as a result of his ill-considered offensives. Obsessed with hygiene, he ‘inspected the latrines whenever he visited a unit’. Having commanded a brigade in the early fighting at the Western Front, he had been withdrawn after reputedly going ‘off his head’.

Hunter-Weston directed a series of abortive attacks towards Krithia beginning on 6 May. Each was hampered by British artillery shortages, confusion about the location of the Turkish positions being attacked and, above all, Hunter-Weston’s ineptitude. Apart from three roughly parallel ravines and a gentle slope towards the Turkish positions, the terrain was relatively flat and open, providing minimal cover (altogether different from the sector the 2nd AIF Brigade had just left). Hamilton suggested that a night advance might be appropriate. Hunter-Weston, however, rejected his chief’s sensible advice, and proceeded to launch a number of unimaginative, repetitive set-piece thrusts in quick succession. In each instance he ordered an advance a long way uphill in broad daylight towards Turkish machine-gunners and sharpshooters who had uninterrupted visibility. On each occasion the British, French, and New Zealand soldiers who had to attempt the impossible were given preposterously little time to prepare themselves for it. All these attacks failed comprehensively.

Unfazed by these developments, ebullient as ever, Hunter-Weston was eager to oblige when Hamilton indicated he was keen to persevere. The conspicuous failure of Hunter-Weston’s approach had reinforced Hamilton’s preference for a night advance, but Hunter-Weston was still opposed to this method. Hamilton was intelligent, cultured, and courageous, but his sensitive temperament did not possess the forceful driving power (which Pompey Elliott had in abundance) to impose his will on subordinates. Again he declined to overrule his divisional commander; once more there were fatal consequences. On 8 May, after another predictable attack had predictably failed — launched by Hunter-Weston in mid-morning, as usual, after the Turks had breakfasted and been alerted by a brief preliminary bombardment — Hunter-Weston ordered the devastated New Zealanders to repeat the exercise in the afternoon. Hamilton decided to cancel this renewed attempt and, in a desperate gamble, ordered instead an ambitious general assault involving other units in the vicinity as well as the New Zealanders.

Late in the afternoon of 8 May the men of the 2nd AIF Brigade, so far mercifully spared from Hunter-Weston’s fiascos, were settling into new surroundings well behind the front, cooking their evening meal and preparing rudimentary shelters for the night. Out of the blue McCay received a message ordering his brigade to advance towards Krithia and beyond. There was, absurdly, only half an hour to attend to all the organisational arrangements and move up to the front line to begin the attack. After being hastily alerted by brigade headquarters, Gartside felt able to give the 7th companies (who were to comprise the right half of the leading waves, though they were then three-quarters of a mile behind the existing front) only two minutes to get ready. In effect, the brigade had been directed to advance along an exposed spur for three miles although they would encounter the same Turkish fire that had demolished a series of similar attacks before any of these advances had managed to progress a sixth of that distance. A 7th private, having just returned after delivering a message to a British unit up ahead, was amazed to learn that such a suicidal manoeuvre had been ordered. He wanted to guide the battalion forward along a protected route that he had discovered via one of the ravines, but there was no time to reconnoitre or to consider such alternatives.

As soon as they emerged into the open they were shelled by Turkish shrapnel. Rifle and machine-gun bullets buzzed around them with growing intensity. ‘Come on, Australians’, McCay repeatedly called, and others took up the cry:

The fire of small arms increased but the heavily loaded brigade hurried straight on, heads down, as if into fierce rain, some men holding their shovels before their faces like umbrellas in a thunderstorm.

Inevitably they lost heavily, but the survivors kept going until their numbers were too thin to go further. They dug in where they were, 400 yards short of the Turkish trenches, still over a mile from the village of Krithia. It was a marvellous display of heroic courage. Onlookers likened it to the charge of the Light Brigade.

It was also a product of murderous and futile folly. Gartside and many others were killed, and the agonies of the wounded were heart-rending. Later that month, after the shattered remnants of the 2nd Brigade had rejoined the AIF, British units at Helles successfully advanced towards the Turkish trenches at night — the penny having dropped at last — with minimal casualties. These manoeuvres were a prelude to another attack on Krithia; this was better planned than its predecessors and began auspiciously before withering, owing to a crucial tactical error by Hunter-Weston, who, astonishingly, had recently been promoted to corps commander. In July he was evacuated from Gallipoli suffering from sunstroke. He ‘should surely have been shot’, concluded one of Pompey Elliott’s men, ‘as he was equal to at least a division of Turks against us’.

News of the 2nd Brigade’s exceptional charge soon reached Elliott. He was delighted to learn that onlookers from other countries ‘were astonished at the reckless daring of our men’, but appalled by the magnitude of the casualties: ‘They tell me there is hardly any left of the poor old 7th Battalion’. By 30 April, in fact, the 7th had suffered more casualties than any other AIF battalion. The Krithia losses completed a devastating initiation for Elliott’s unit.

There were hardly any of the original officers left. Two had been retained offshore on other duties — Tubb, as battalion transport officer in charge of the horses, and McCrae, on a temporary secondment to an engineers’ unit. Of the remaining 29, only two combatant officers were still going strong, Grills and Weddell. Both knew they had been very lucky. ‘A man never realizes … what a terrible thing war is until he has been through it’, wrote Grills after Krithia. ‘Anyone fortunate enough to get off with his life in this Bloody Struggle … ought to thank God’. Jackson, Layh, and Heighway were away undergoing treatment for wounds received near Fisherman’s Hut; Chapman, also hit during the fighting there, died, as Alan Henderson did, on the way to Alexandria. Killed during the battle further south on 25 April were McKenna (who bled to death after his leg was blown off), Blick, and Davey. The severely wounded included Blezard, Conder, Connelly, Denehy, Mason, and Swift. Scanlan had emerged unscathed from the ordeal in front of Fisherman’s Hut, but received a bullet in the chest at Krithia and was sent home to Australia.

De Ravin had a lucky escape. Having offered his men a final cigarette before the landing, he had pocketed the emptied container, joking that bibles and packs of cards had saved soldiers’ lives before and a cigarette case might prove just as handy; after he waded ashore that case actually proved his salvation, deflecting a bullet that struck him over the heart. But he was not so lucky at Krithia, where an enemy projectile smashed his big toe. Birdie Heron emerged from the landing with two head wounds from shrapnel, but rejoined the battalion in time to collect another in the charge at Krithia; this third one proved more serious, resulting in the loss of an eye. Jimmy Johnston, having missed the landing because of an infected throat, lived up to his colonel’s high expectations by his conduct at Krithia, but was gravely wounded in the charge when several bullets hit him in the stomach. The adjutant, Captain Finlayson, whose wedding was a social highlight of the training period at Broadmeadows, sustained multiple fractures in his right leg, which eventually had to be amputated. Also hit at Krithia was Captain Hunter, the famous athlete–footballer who had assured the people of Bendigo on behalf of that city’s original enlisters that ‘there would be no beg pardons’, and ‘while all could not expect to return they were prepared to take a sporting chance’. Wounded in the foot, he was taken to the rear; he was lying on a stretcher having his wound dressed when a stray bullet happened to strike him, with fatal consequences.

That was not all. Elliott was dismayed to hear that Rupert Henderson had been killed at Krithia. ‘It is dreadful for the Hendersons to have lost both their boys like this’, he wrote, ‘they were so splendid and brave all through’. McCrae, having ‘passed through a most awful week of mental stress’ aboard a ‘luxurious’ ship while his ‘men and brother officers were short of rest, food and water and fighting for their very existence’, felt ‘awfully sorry for the Hendersons, it must be a terrible blow losing two sons like that’. The elder brother of Rupert and Alan, a teacher, was interrupted in the classroom one morning and handed a message. ‘When Henderson read the telegram’, one of his students later wrote, ‘he turned white and rushed from the room’. The mother of these sons, an indefatigable volunteer for many years in a host of social service activities, had a nervous breakdown in 1915. The Bishop of Bathurst, headmaster of Trinity Grammar School during the Hendersons’ years there, described Rupert in May 1915 as the finest individual he had ever had in his charge.

About a week after Pompey Elliott heard about Rupert Henderson’s death, he also learned that Jimmy Johnston had succumbed to his wounds and that General Bridges had been fatally wounded. ‘What will be the end I wonder’, he mused. His feelings about the decimation of his battalion and the loss of officers he particularly admired were candidly expressed in a letter he sent to the Henderson family with his ‘deepest sympathy’. Alan, he wrote,

was in the firing line the whole time from the landing, encouraging the men to advance and holding them to it when their losses counselled retreat … Rupert first learned of his death just before leaving the Gaba Tepe landing place for Cape Helles. He was informed of Allan’s death by Lieut Johnston, who had not landed in the first instance here owing to illness but had gone to Alexandria with wounded and returned in time to take part in the great charge near Krithia, which has rendered the name of the Victorian Brigade and in particular the 6th and 7th Battalions famous throughout the Army here, in which both Rupert and he fell. I have felt the death of these two more than all the others and they are many, for the 7th Battalion at present is little more than a name. Both Johnston and Rupert came in a peculiar degree under my instruction in the 5th AIR and both had they been spared would have earned a great name. I asked both personally to join me in the 7th before they had decided to volunteer and I never had the slightest reason to doubt my judgment, but every day confirmed it more and more. No one could have been more loyal and trustworthy than they, and indeed all my officers, proved. But I feel peculiarly responsible for their deaths and though there is no doubt that they would have come in any case, I cannot forget the fact that it was by my invitation they came … I enclose a scrap of paper which you may treasure. It is the last message I received from Rupert. I was wounded a few minutes afterwards.