CHAPTER THIRTEEN

‘I Would Have Gladly Welcomed a Shell to End Me’:

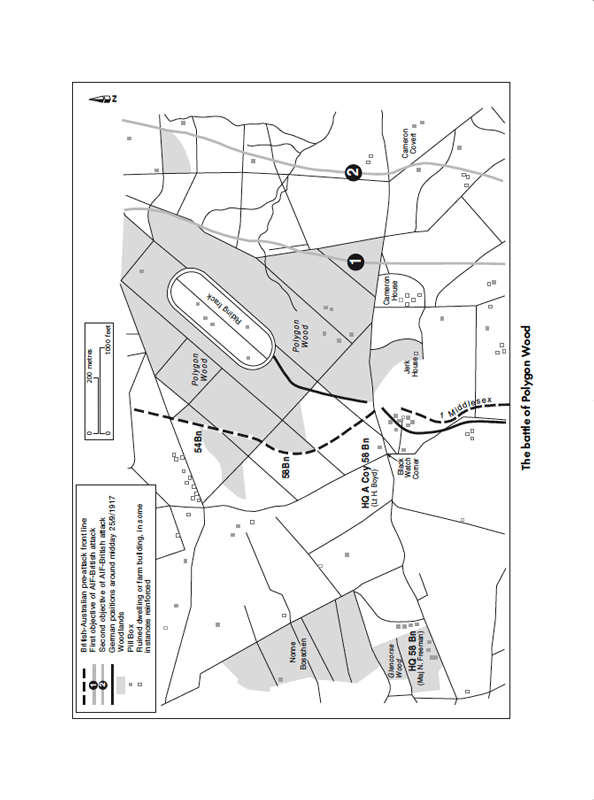

The battle of Polygon Wood

SEPTEMBER–NOVEMBER 1917

IT WAS HAIG’S keenness to launch an offensive in the north that resulted in the challenging task Elliott and his brigade were given in September 1917. Haig had long fancied the notion of a drive north-east from Ypres across the fields of Flanders to the Belgian coast. A successful onslaught there would not only begin the process of liberating Belgium from German occupation, the objective that had ultimately prompted Britain to enter the war. It would also dislodge the Germans from both the tactically important Belgian ports and the advantageous higher ground east of Ypres. But how likely was this ambitious Flanders venture to be successful? Haig’s detractors in British strategic circles were sceptical; previous offensives under his direction afforded little basis for optimism. But with the French and Russian armies in very ordinary shape in mid-1917, Haig felt that the onus was on Britain to do something. Eventually he was reluctantly authorised to proceed.

Pessimism was understandable after three years of stagnation. But there were lessons to be learnt at the Western Front, and some commanders were learning them. With the refinement of artillery techniques, the innovation of Stokes mortars and Lewis guns, and the adoption of the creeping barrage (a mobile curtain of shellfire moving forward at a pre-arranged pace just ahead of the advancing infantry it was protecting), a carefully planned attack on a limited portion of enemy trench now had a good chance of success. There had previously been a critical gap between the end of a set-piece preliminary bombardment and the arrival of an attacking force at its objective, but this window of opportunity for defenders was gradually closed by the increasing sophistication of the creeping barrage. Such innovations had impressed Elliott, and convinced him that with careful preparation fewer lives need be lost in making successful attacks. ‘Our Artillery and trench mortars are so perfect now’, he wrote in February 1917, ‘it is only very occasionally that one should have to charge in the old bull at a gate fashion’.

But these improvements did not pave the way for a decisive breakthrough. The ultimate war-winning stroke that Haig in particular hankered after remained as elusive as ever. Even a well-prepared and initially successful advance tended to run into trouble as attackers pushed forward beyond the range of their supporting artillery. The defenders could usually rush reinforcements (particularly by rail) to the threatened area more quickly than the over-extended attackers could get their guns forward.

The answer, some perceptive commanders began to realise, was to aim at a series of achievable step-by-step advances instead of an unrealistic big breakthrough. Under this ‘bite and hold’ approach the idea was to choose a feasible chunk of enemy-held territory; unleash an irresistible protective barrage; get the infantry forward close behind it; mop up any lingering resistance; consolidate the captured ground in order to ward off any hostile response; and then stay put for a few days while the guns were brought forward and thorough preparations were made for the next phase in the offensive.

In June 1917 General Monash’s Third AIF Division participated in a successful advance by General Plumer’s Second Army at Messines, five miles south of Ypres, that came to be hailed as a bite and hold classic. Before this battle, with his division about to participate in a major operation for the first time, Monash had nervously acknowledged that the cards seemed stacked against attackers at the Western Front, but success at Messines converted him into a bite and hold enthusiast: ‘I am the greatest possible believer in the theory of the limited objective’, he declared.

Was the Flanders campaign to be based on bite and hold techniques, or was it to be another bid for the big breakthrough? Haig was ambivalent, but made his preference clear by his choice of commander to direct it. Instead of Plumer, who was familiar with the area and had just supervised the Messines triumph, Haig put Gough in charge, influenced by his reputation for decisive dash and vigorous pursuit. After conspicuous preparations and a bombardment lasting more than a fortnight, the offensive began fairly well on 31 July, but ran into severe difficulties in August. Enemy resistance was effective, and the attackers’ problems were magnified by the impact of rain on a clay battlefield where the water level was high and the drainage ruined by shellfire. Haig responded by switching to an unambiguously bite and hold approach, relegating Gough to a subsidiary role and reinstating Plumer as commander. With the well-rested Australian divisions about to become involved in the offensive (which became known as the Third Battle of Ypres), this was a pleasing development in AIF circles. After Bullecourt the prospect of attacking under Gough was distinctly unpalatable.

About Plumer, on the other hand, there was no such concern. If there was one principle becoming ever-clearer at the Western Front, it was that careful preparation was essential if attackers were to have some chance of success, and no army commander heeded this lesson more effectively than Plumer. Methodical and painstaking, he and his first-rate chief-of-staff Major-General ‘Tim’ Harington managed to instil in the units fighting under them a well-founded confidence that they had attended to every possible organisational detail before committing men to confront the enemy. The talented Plumer–Harington partnership had already impressed Monash and other AIF leaders.

Elliott was soon singing the pair’s praises as well. With preparations for the next phase of ‘Third Ypres’ in full swing under their capable direction, Plumer scrutinised a simulated 15th Brigade attack on 8 September. ‘He is a funny little red faced man, very white hair and moustache’, Elliott reported, ‘but is a good General’. And of all the British staff officers Pompey encountered during the war, Harington was ‘the only one … who ever impressed me that he had a proper conception of his job’; this Pompey defined as the adoption of appropriate measures ‘to save the infantry casualties’.

That simulated attack on 8 September featured new methods introduced in response to the system of defence now being adopted by the Germans. In the continuing evolution of Western Front tactics the Germans had instituted a system of defence in depth, eschewing rigid lines of trenches in favour of a more fluid structure based on hundreds of mutually supporting concrete machine-gun nests. These blockhouses, shrewdly located and practically impervious to shellfire, became known to their assailants as pillboxes. A pillbox could be vacated when necessary much more quickly than a deep underground dug-out, and could also be used as an effective springboard for counter-attack. This was a crucial attribute: the German policy was now to occupy the front lightly in scattered posts, allow any advance towards them to penetrate so the attackers could become over-extended and vulnerable, and then hit back hard with a swift and sudden counter-thrust. The British had also come to favour defence in depth, but the main focus in the AIF’s training in the lead-up to Third Ypres was new offensive tactics, in particular how to deal with pillboxes and German counter-attacks. Platoons were now encouraged to see themselves as self-contained units, equipped with their own specialist sections (bombers, Lewis-gunners, scouts, snipers, moppers-up) to overcome pillboxes and other enemy strongpoints on their way forward, without being so held up in the process that they lost the protection of the creeping barrage.

During the long spell enjoyed by most of the Australians there were briefings and drills galore to familiarise them with these new methods. At the 15th Brigade Elliott supervised this training with characteristic robustness. During one exercise Lieutenant Charles Noad, a 15th Brigade newcomer who had just completed an officers’ course after being wounded at Pozières, became a target for the unmistakeable Pompey bellow:

‘Who’s in charge here?’

‘I am, sir’ (from Noad).

‘What are those men doing there? A bloody lance-corporal wouldn’t have them doing that!’

Also influential was Wagstaff’s successor as Hobbs’s chief-of-staff, Lieutenant-Colonel J.H. Peck, who had demonstrated admirable bravery, skill, and humour in a variety of AIF appointments since 1914. Peck was able to pass on useful insights gleaned from the battle of Messines, where the AIF encountered the German defence in depth and implemented the new attack methods successfully. Pompey’s confidence that his men would be able to execute them proficiently was vindicated by their performance in the brigade exercise on 8 September, when Plumer ‘said he was pleased with my boys’. The following day the 15th Brigade was advised to get ready for an imminent move to Belgium.

So Elliott had to steel himself, together with thousands of veterans under his command, for a return to the slaughterhouse. They knew the horror awaiting them. They knew that their senses and sensibilities would be violated by deafening noise, hideous stench, appalling sights. They knew that the damage their nerves had sustained in previous exposure, unhealed even after such a prolonged rest, had left them less equipped than ever to cope with such an ordeal. Pompey in particular, whose temperamental endowment was hardly phlegmatic, had to muster tremendous willpower to maintain, in circumstances of paralysing stress, the distinguished leadership he had so far displayed.

Elliott arrived at Steenworde with his brigade on 17 September, aware the AIF was about to spearhead the step-by-step resumption of the Third Ypres offensive. The First and Second Divisions were to launch it on 20 September, with the Fourth and Fifth Divisions to undertake the second phase a few days later. ‘[From] what I can see it’s going to be “some” fight that we’re going into’, Elliott told Belle:

if my luck is out I know you’ll do your best to help [Katie] and the wee people over the stiles till they are able to look after you … The guns are booming like the waves on the shore again — drumming to call us to battle and for many of us beating our funeral marches at the same time. If I could leave [Katie] and the wee people a little more money I would go willingly since men must die that we may be quit of the old Kaiser and his soldiers, and it may as well be me as the next man … my poor boys have to face it all time after time, and it is up to the officers (even the highest) not to shrink from what their men have to face. But whether we shrink or whether we don’t, we must each and all go into it with what courage we can muster.

The first battle was an uplifting success. On 20 September the Australians advanced close behind an awesome barrage, their determination and confidence redoubled because two AIF divisions were attacking side by side for the first time. All objectives were taken, German morale was shaken, and the sadness over individual losses was countered by the elation in the AIF at such a comprehensive victory. Elliott was delighted:

Our boys particularly the old 7th have made a glorious advance and captured a whole lot of Bosches and driven [them] back a long way … That will be another feather in our boys’ caps for the British troops have been blocked along this line for about a month. I hope we will do as well when our turn comes, which will be very soon now.

It was not until later that he learned that Major Fred Tubb VC had been hit. Wounded by a sniper after gallantly leading his men towards a group of nine pillboxes (all eventually captured by his company), Tubb was being carried back on a stretcher when he was struck by a shell. He was rushed to a dressing station, but did not survive.

On 20 September the Australians had attacked on a 2,000-yard front and successfully advanced, in three stages, about a mile along the main ridge east of Ypres. The next step, once the guns were brought forward, involved a further advance of about three-quarters of a mile on a similar front. If this operation went according to plan, a third battle was envisaged: a drive to the crest of the ridge following its northward curve towards Broodseinde. In the second step two AIF divisions were once again to move forward side by side in the centre of the attack, while the British X Corps conforming on the right secured that flank and Gough’s Fifth Army carried out a similar task on the left.

Dominating the Australian sector of the advance was Polygon Wood. This formidable stumbling block comprised a tangle of shattered trees, obstructive undergrowth, shell craters, trenches, and pillboxes together with a creek, a riding track, and a prominent mound providing sweeping observation for the Germans. The western side of Polygon Wood had been the Australians’ final objective on 20 September. Their task in the second battle was to sweep through it and establish themselves beyond it. The Fifth AIF Division, being fresher than the Fourth, was given the harder task on the right. Two brigades from each division were to attack. Hobbs chose Elliott’s 15th and Brigadier-General C.J. Hobkirk’s 14th as the Fifth Division’s assaulting brigades, with the 15th in the more onerous position on the right of the divisional front, the 14th on its left and Tivey’s 8th behind in reserve. Pompey’s men, therefore, had been given the most demanding task of all the brigades involved in the battle.

The attack was to be undertaken in two distinct parts. First, an advance of half a mile would be made to the far (eastern) edge of Polygon Wood (the red line). After consolidation and reorganisation, the advance was to resume with a further drive east of about 350 yards by fresh units to the final objective (the blue line). Elliott allocated the first phase to the 60th Battalion, with the 57th and 59th to undertake the later advance to the blue line. The 58th would occupy the front line before the battle, and remain there as a garrison and brigade reserve after it started.

Elliott’s decision on the 58th’s role was perhaps influenced by the absence of its commander as well as the fact that it had suffered more than any other 15th Brigade battalion in its last engagement (Bullecourt). Denehy, increasingly troubled by the stress of command, was granted a fortnight’s leave in September. Returning shortly before the battle, he was placed in charge of the Fifth Division nucleus (the portion of each unit now customarily kept out of a major action to facilitate the restoration of morale and esprit de corps should heavy casualties be incurred). The 58th went into action under Major Neil Freeman, a 27-year-old solicitor and renowned footballer from Geelong, which had strong links to the 58th. Freeman lacked experience as a battalion commander, but Pompey was convinced he was a leader of abundant promise. He so distinguished himself at the Aldershot course for prospective colonels that he had been offered (but rejected) a position there as an instructor.

Two 58th companies filed smoothly into the 15th Brigade’s portion of the shell-cratered front in the south-west corner of Polygon Wood late on 23 September. The following night they watched a relief of the British troops on their right degenerate into confusion. What they saw did not inspire confidence in the 98th British Brigade, which was to make a complementary advance and secure their flank in the battle. Nor did the unwillingness of the 58th’s newly arrived front-line neighbours, the 1st Middlesex Regiment, to occupy the disturbing gap between them and the Australians; this task was, under the stipulated formation boundaries, unquestionably the 98th Brigade’s responsibility. The commander of the furthest right 58th company, Lieutenant Hugh Boyd, did his utmost to persuade the British to extend leftwards, but it was not until a squad under Sergeant Jack Colclough, a 33-year-old farmer, spent all night digging across towards the Middlesex that the gap was partly closed.

Meanwhile Pompey Elliott was being frustrated by several disruptions to the 15th Brigade’s preparations. Shortly before the battle Legge departed, having been promoted to brigade major in the 14th Brigade; he was replaced by Roy Gollan, a 25-year-old Geelong journalist. Elliott’s familiarity with his new staff captain was limited to the months Gollan had spent in the 58th Battalion in 1916. In this major operation, then, Pompey’s principal assistants would be a brigade major he lacked confidence in and a staff captain he hardly knew. Moreover, although he was well accustomed to improvising by now, the headquarters assigned to his brigade — a sizeable dug-out in a vast mine crater at Hooge (three miles east of Ypres) — was, he felt, demonstrably unsuitable. On his arrival there he found the dug-out very wet and already occupied by the headquarters of other units. He had to ‘reduce Brigade Staff to an absolute minimum, and even then it was absolutely impossible for them to gain any proper rest or to have proper organisation or to arrange for the record of events’.

Elliott was also perturbed by the late arrival of the operation order from Fifth Division. There was not enough time for the contents to be properly absorbed, passed on, and implemented. With his brigade scheduled to attack at dawn on 26 September, he organised a conference with his battalion commanders at Hooge crater on the evening of the 24th, primarily to discuss issues arising from the divisional order — which did not materialise until 10.30pm, after the conference had concluded.

One directive in the order particularly annoyed the brigadier. In his brigade’s extensive training for its next assignment it had practised attacking on a three-company frontage. According to Pompey, this method was adopted with Hobbs’s imprimatur, was practised ‘with great success’, and was eminently suited to his brigade’s task at Polygon Wood (advancing through woods had been a feature of the 15th Brigade’s training routine as long ago as June). When the Fifth Division operation order arrived, however, it prescribed a two-company frontage for the attack (and, because the advance to the blue line was to be undertaken by two battalions, each of them would have to adopt a one-company frontage). Elliott sought permission to use the method his men had practised, but Hobbs insisted that any such variation was out of the question. His order had been approved by White and could not be altered, he insisted with dubious justification. By then, however, the 15th Brigade’s preparations were being dislocated by the most serious disruption of all.

The Germans, stunned by their defeat on 20 September and correctly sensing that another British attack was imminent, tried to thwart it with an assault of their own. At 5.15am on 25 September a ferocious bombardment suddenly descended on the 58th and 1st Middlesex, and immediately began to inflict sizeable casualties. Never before (as British intelligence later concluded) had German artillery concentration been greater. Never before had the 58th endured such intense shellfire. Germans in large numbers were spotted advancing behind this onslaught.

Lieutenant Boyd reacted decisively. Leaving his headquarters (a formidable pillbox near the crossroads at the south-western edge of Polygon Wood known as Black Watch Corner), Boyd fired the SOS signal, moved forward to the front line with his support platoons, and took control there. Major Freeman sent Boyd two further platoons from battalion reserve. The Middlesex, overwhelmed by this tremendous assault, fell back in disarray. The Germans made strenuous efforts to drive the 58th back in similar fashion, but did not succeed. A Prussian officer, leading his men from the front, materialised near the gap that Sergeant Colclough’s squad had attempted to occupy. Colclough, arriving seemingly from nowhere, bayonetted him, hit the ground again to evade enemy machine-gunners, and then shot the next two closest Germans. His resourcefulness deterred other attackers in the vicinity. They wavered, turned back, and sought cover in nearby shell holes.

Pompey’s men held on with superb tenacity. The alarming German penetration on the right enabled enemy machine-gunners to assail the 58th with oblique and enfilade fire. Boyd responded by swinging some of his men around to face the flank incursion, but they also had to contend with menacing machine-gun fire from low-flying German planes. When Boyd realised the Germans had reached the Middlesex support line he sought from Freeman, and was given, the two remaining platoons in battalion reserve. To reach the front line, these reinforcements had to go through an avalanche of German shells. Inevitably some men were hit, but the survivors persevered spiritedly and joined their beleaguered comrades. Boyd was proud of the 58th’s morale and skilful resistance in a very tight corner, but he felt that the situation ‘was becoming hourly more precarious’.

The shellfire was exceptionally intense, extensive, and prolonged. Pillboxes captured by the AIF five days earlier were particularly targeted. The Germans knew their precise location, and correctly presumed Australian commanders were occupying them. An evident priority was the redoubtable pillbox near the eastern edge of Glencorse Wood, 600 yards behind the support line, which was chosen by Freeman as his headquarters. Although its structure survived numerous direct hits, the concussion was so severe that pigeons inside it (used to carry messages) did not survive; outside, there were numerous casualties as runners and others in the immediate vicinity were hit. Similarly, Elliott’s headquarters at Hooge crater, two miles behind the front, was a ‘very unhealthy’ place that was ‘shelled all the time’ (Stewart later wrote).

Even further back the shellfire was also extraordinary. Hobbs was on his way to Elliott’s headquarters early that morning for a final discussion about the next day’s attack, but the barrage he encountered while proceeding east along the Menin Road to Hooge convinced him it would be suicidal to venture any further:

I stopped numerous convoys, cars and men from going to almost certain death. Dumps were going up in all directions. Motor lorries and cars burning along the Rd, broken down wagons, dead men and horses. I tried to get on but after going on for about 500 yds found the Road completely blocked. I hesitated and then decided to go back. 3 minutes after a lorry full of ammunition just ahead of where I stopped blew up with a tremendous explosion — a very narrow escape indeed.

It was obvious that this German onslaught would succeed in sabotaging the AIF’s Polygon Wood operation unless the disturbing situation on the right could be swiftly retrieved. Just before nine o’clock a message reached Elliott from Freeman requesting a company of reinforcements. Pompey immediately arranged for a 60th company to be sent forward. That battalion was supposed to be spearheading the attack in 20 hours’ time, but the brigadier had little alternative. There would clearly be no AIF attack at all unless this incursion was repulsed. He instructed Freeman to get in touch with the Middlesex and organise a combined thrust to eject the Germans and regain the front line; Freeman was to let him know when this counter-attack was to begin so he could co-ordinate a barrage to support it. Freeman did his utmost, but could find no Middlesex officer able to make the arrangements.

Hobbs could not get to Hooge, but Marshall, Stewart, and Mason managed to present themselves there for a ten o’clock conference at Elliott’s headquarters. The brigadier had summoned them for a briefing on the divisional order, particularly to clarify the unpalatable change in attack formation insisted on by Hobbs. There seems to be no record of Pompey’s mood at this stage, but it was presumably explosive. That his men had to discard a method repeatedly practised by them and suitable for their task was infuriating; discovering this change so late that he had to put his battalion commanders’ lives in great peril to tell them about it was intolerable. Visiting Hooge crater then was decidedly dangerous, as Mason testified:

The appearance of the place baffles description; the approaches were being heavily shelled and bombed, the dump was wrecked and ammunition and bombs were littered all round, and several motor lorries were wrecked and one blazed fiercely.

While Elliott was with his colonels they also discussed the situation on the right, and the possibility that further reinforcements might be required.

Their conference had just concluded when a message arrived from Brigadier-General J.D. Heriot-Maitland, commander of the 98th Brigade. This message stated that the 1st Middlesex would be counter-attacking at two o’clock to re-establish themselves in their front line. Heriot-Maitland had not formally taken over command of the sector when the Germans launched their assault, and remained unaware for some time that his brigade was being attacked. While considering his response he was told not to concern himself with the need to have fresh men for the following day’s operation; recapturing the front line had to be his main and immediate priority. This instruction came from Major-General P.R. Wood, who was commanding the 33rd British Division for a few months in the temporary absence of the unimpressive temperance zealot who led it for two years, Major-General R.J. Pinney.

Elliott had already sent a second 60th company into the fight, and now decided to send its last available company as well (the other being engaged, like two of the 57th, on carrying duties). About this time a concerned 58th officer, having made his way to Hooge crater to suggest that Freeman could do with a company of reinforcements, received instant reassurance when he approached the brigadier. ‘A company’, replied Pompey, ‘my boy, you shall have the whole of the 60th’. Elliott directed Marshall to accompany the last 60th company forward and take charge there when he arrived. Pompey then sent another message to Freeman, instructing him to support the 2.00pm British counter-attack with the 60th Battalion reinforcements he had been given. The brigadier also outlined the barrage organised for this advance, and advised that Marshall was moving forward to take over.

For Boyd and his weary 58th stalwarts hanging on resolutely, the news that Marshall was coming to their aid was heartening indeed. As Bean acknowledged, in a ‘tight corner the mere knowledge that Norman Marshall was in charge would give confidence to all Australians who were aware of the fact’. Boyd had already been buoyed during this most harrowing day of his life by an encouraging message from Marshall.

But relentless German shellfire continued to make it very difficult for reinforcements and carrying parties to get forward. A lieutenant supervising a 57th party lugging ammunition to a dump at Glencorse Wood was killed close to Pompey’s headquarters, and a number of his men were hit. The 60th company engaged in similar toil suffered so severely that Marshall had to send another lieutenant to reorganise it. For the other 60th companies, advancing to reinforce the 58th, the barrage deluging Glencorse Wood was a nightmare. As they gallantly proceeded in single file, a few yards apart, along the track that was the only way forward in the treacherous, shell-cratered wilderness, it seemed inconceivable that they could escape the thunderous missiles crashing all around them. The commander of B Company and over 20 of his men were hit, and A Company soon lost over 60, including two officers. These casualties seemed miraculously light, so devastating was the shellfire.

Boyd, in accordance with Elliott’s instructions (conveyed via Freeman), arranged for some of the 60th reinforcements to advance in support of the scheduled 2.00pm counter-attack by the 98th Brigade. However, there was no sign of the Middlesex. Two companies of Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders managed to establish a partial line in the 98th Brigade’s sector, but it was still well behind the previous front and 350 yards behind Boyd’s position. Boyd’s anxiety about the vulnerability of the exposed 60th men was accentuated by his glimpse of Germans massing ominously ahead near the pillbox-reinforced strongpoints known as Jerk House and Cameron House. Eventually, around five o’clock, Boyd decided to withdraw this 60th fragment.

Shortly afterwards, having been delayed by a communication mix-up, Marshall and his intelligence officer, Lieutenant Stillman, arrived at Freeman’s headquarters. They quickly appraised the situation. Stillman felt ‘things were becoming very serious on the right’. Marshall sent Elliott a frank assessment:

Am at 58th Battalion headquarters. Position appears bad. Enemy reported by [Boyd] at 5pm to be again massing near Jerk House and Cameron House. Brigade on our right have not retaken their front line and can get nothing definite from them. Our right is still intact but line is now badly knocked about and would have very bad time if attacked in flank. Enemy aeroplanes flying very low and machine-gunning freely. Have formed the opinion that enemy intend counter-attacking at dusk. Enemy barrage very heavy on our support and reserve lines and it is almost impossible to get reserves [forward] until dusk … Consider you should insist on the British Brigade on our right retaking their front line at once and link up with us otherwise relief tonight must suffer very severely. Intend sending two companies into line at dusk or as soon as possible thereafter. Still suffering heavy casualties.

Marshall then proceeded further forward to confer with Boyd, who was delighted to see him. For twelve hours the 31-year-old Bendigo dentist had carried the harrowing front-line responsibility for a critical situation that was being followed with concern by all his direct superiors in the military hierarchy right up to the Commander-in-Chief himself. (Major-General Harington was to write in his biography of Plumer eighteen years later that it was a ‘very disconcerting’ time, ‘which I remember well’). Boyd had risen to the challenge superbly, but was glad to hand over at last to someone more credentialled. Marshall ‘at once grasped the situation tho he had not seen the front on any portion of this sector’, Boyd later noted admiringly, and directed the only 60th company not yet called into action to bolster the right flank straightaway. Its commander, 35-year-old Wilfred Beaver, had overlapped with Harold Elliott at Ormond College during a distinguished scholastic career before becoming a magistrate in Papua, where he collected material for a book later published with the title Unexplored New Guinea. The way Beaver led his company straight to the thinly held position it was to reinforce ‘was worthy of great praise’, Marshall considered, but just as Beaver arrived he was fatally wounded.

Back at Hooge crater Elliott received a message from the 98th Brigade shortly after Marshall’s front-line report arrived. Marshall had highlighted the plight on the right, urging Elliott to exert maximum pressure on the 98th Brigade to rectify the situation. Pompey had been sceptical of earlier British claims that the 98th had recaptured its front line, a recovery not verified by Freeman. The vague message from Heriot-Maitland that arrived within minutes of Marshall’s appraisal merely confirmed Pompey’s impression that the British had no idea about the state of affairs on their front or even where their units were. With minimal help to be expected from that quarter, and with Freeman describing the situation in similarly pessimistic and precarious terms as Marshall, Elliott reacted with characteristic decisiveness: he committed another of his battalions to the fray, Cam Stewart’s 57th.

Among the 57th’s men wondering what the next day’s battle might bring was its vivid chronicler ‘Jimmy’ Downing. ‘Despair, hope, despondency and resolution fought for the possession of each soul’, he observed, as shells ‘roared and moaned incessantly’ and ‘ragged iron whirled and burred’. Moving forward earlier than expected in response to Pompey’s urgent summons, Downing and his comrades sensed the shellfire intensifying. Then they reached Glencorse:

There was a crash close by, a red flame, flying sparks. Another — and two men in the flash, toppling stiffly sideways … one with a fore-arm partly raised, the other lifted a little from the ground, with legs and arms spread-eagled wide — all seen in an instant — then a second of darkness, then shells, big shells, flashing and crashing all around … we stumbled past the reeking bodies as nearly at a run as our exhaustion permitted — heads down as though it were a hurricane of rain, not ripping steel. By the red and flickering light of the shell-bursts men were seen running and staggering, bent low. They dropped into what had been a trench, … enduring with tautened faces, lying close to the ground, crouching as they burrowed for dear life with their entrenching tools, while the storm of steel wreaked its fury on tortured earth and tortured flesh. There were on all sides the groans and the wailing of mangled men … The smell of burnt explosive was thick and pungent. Bodies, living and dead, were buried, tossed up, and the torn fragments buried again.

Before the 57th Battalion began its approach to the front, Charles Noad, nervously preparing to go into action for the first time as an officer, was heartened by the philosophical fatalism of his experienced captain, Herb Dickinson. ‘Go for your life’, Dickinson advised Noad, ‘if your name’s on it you’ll get it and you can’t do much about it’. Noad’s platoon was practically decimated in Glencorse Wood. One of his worst moments occurred when the column led by Dickinson halted and Noad heard men calling for the captain. As Noad feared, one of the shells bombarding the wood had Dickinson’s name on it. After further casualties Noad found himself in charge of Dickinson’s shaken company. As well as Dickinson, two other company commanders were killed while the 57th proceeded through that dreadful place, Captain Aram and Lieutenant Gerald Joynt (whose brother was to win the VC with the 8th Battalion).

Elliott had directed Stewart to ‘re-establish any part of our right flank which is abandoned, and form a flank to connect up with the British’. Stewart coolly scrutinised the situation with his adjutant and Lieutenant Roy Doutreband, his intelligence officer. Their personal reconnaissance confirmed that the 98th Brigade, despite its claims to the contrary, had no men in its sector (though some had joined the Australians on the 15th Brigade’s right) forward of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, who were positioned well behind the AIF front. Stewart distributed his men for maximum flexibility. One company filled the gap on the right between these Highlanders and the existing 15th Brigade front (in accordance with Elliott’s instructions). The other three companies were positioned in reserve nearby, ready for use as and where needed.

It was now inconceivable to Elliott, as he told Hobbs in no uncertain terms, that his brigade could attack Polygon Wood the following morning. The 98th Brigade’s promise to regain its front line, virtually a prerequisite for the planned operation to succeed, had not been kept. In view of its performance so far, the likelihood that it would be able to fulfil its obligations if the attack went ahead as scheduled had to be slim. The consequences for Elliott’s men, vulnerable to flanking fire as they advanced, would be calamitous. Besides, his own brigade had already suffered acutely. The 58th had been severely mauled, and the 57th and 60th, two of the designated assault battalions in the operation, were in no shape for such a role. Moreover, the relentless German shellfire, as well as making it impossible for units to approach Polygon Wood without sustaining heavy casualties, had disrupted the attack preparations in other ways. Practically all the supply dumps accumulated for the operation had been destroyed. The important tape-laying to pinpoint assembly positions might well be detected by the Germans who had penetrated on the right. Tapes already positioned to mark forward approaches had been shot away. Nearly all the specially trained 58th guides had become casualties.

Elliott pointed all this out vigorously to Hobbs, who responded that the operation had to proceed nevertheless. This decision had been made, not without considerable anxiety, at a higher level; there would be significant modifications arising from Pompey’s forceful representations. Accepting that the 57th, 58th, and 60th were too shattered and shaken to participate as assault battalions, Hobbs directed that the advance to the red line would now be carried out by the 59th, and two battalions from Tivey’s brigade in divisional reserve would undertake the second phase. As for the all-important issue of the 98th Brigade’s capacity to get forward on the right, Hobbs assured Pompey that redoubled pressure was being applied to Heriot-Maitland by his superiors to ensure that this occurred, and at least the British commanders were now conceding that their earlier reports that their men had regained their front line were mistaken. As well, special counter-battery action would be taken to subdue the enemy artillery that had tormented Pompey’s men.

It was with ‘the utmost anxiety’ that Elliott rapidly overhauled the arrangements for the attack. The extra units he had been given would be operating in most unfamiliar territory: ‘not a single officer, NCO or man of the two 8th Brigade Battalions had ever been as far as Brigade HQ, and it was necessary for us to provide guides for them even to that place’. Pompey immediately notified Marshall — ‘Division insists carrying out plan’ — asking him to inform Freeman and Stewart of this decision, and to take responsibility for the front-line organisation of the attack (guiding the assault units to appropriate starting positions in particular) while Stewart took charge of the defence.

Elliott’s other battalion commander, Mason, was on his way forward with the 59th when he learned to his surprise that his men would be undertaking the advance to the red line instead of the second-phase task they had practised. But this last-minute switch affecting the 59th was the least of Elliott’s worries. Confident that Mason’s men were familiar enough with the whole operation to adjust to their changed role satisfactorily, he was far more concerned about Tivey’s battalions and the problem of getting supplies forward to replace the destroyed dumps. Frantically busy, Pompey did not waste words when Mason called at his headquarters. He quickly confirmed that the operation was on, and the 59th was to do the first part instead of half the second.

‘So do you know what to do?’

‘Yes’, replied Mason.

‘Well then, go and do it’.

Just after midnight the commanders of the 8th Brigade battalions assigned to the second phase, Lieutenant-Colonels Muir Purser (29th) and Fred Toll (31st), arrived at Hooge. Elliott gave them a hurried briefing in the limited time available.

During that tense, busy night Pompey’s men did him proud. Freeman’s weary 58th survivors were relieved in the front line by the 60th. Marshall, establishing his headquarters at Black Watch Corner, directed the preparations in the forward area. In allocating the vital tape-laying tasks, he shrewdly adhered to arrangements anticipated until the last-minute changes. His own intelligence officer, Stillman, set the tapes for the red line battalion, even though the 60th Battalion had been replaced in the attack; likewise, Doutreband did for the 31st Battalion what he had been expecting to do for the 57th, and Lieutenant J.W. Francis did the honours for the left blue line battalion even though his own 59th was attacking in the first phase. Guides from the 58th Battalion led the assault battalions forward from Hooge crater to Black Watch Corner. Sentries from the 57th and 58th were posted en route to prevent anyone missing his way in the dark. A 58th company formed a protective screen in front of the assembly positions. Two 57th companies (one without any officers after Glencorse Wood) and a 58th party made a sterling contribution carrying rations, water, Stokes mortars, grenades, and other ammunition to Black Watch Corner.

All these preparations benefited from the Germans’ understandable belief that they had succeeded in preventing the scheduled AIF operation. This conclusion prompted them to ease their shelling of AIF positions during the night (although Doutreband’s ten-man tape-laying party was caught by a sharp bombardment, and only one beside himself was not hit). Even so, it was an impressive display of brigade cohesion. Mason was full of praise for the assistance his men received as they proceeded smoothly forward and Stillman efficiently led them to their assembly positions. ‘Everything went without a hitch’, Mason enthused. There was the odd hitch affecting the movement of the 8th Brigade battalions, but they were correctly assembled in time. ‘The last man was accurately placed in his position exactly 20 minutes before zero’, Pompey declared proudly, ‘in spite of difficulties which at first appeared insurmountable’.

The men under his command had done superbly, but he was powerless to alleviate his greatest concern of all — the situation on the right. Heriot-Maitland had arranged for two battalions to move forward during the night and recapture the front-line sector yielded by the Middlesex. The battalions assigned to this task were the 98th Brigade’s reserve battalion, the 4th Suffolk Regiment, and a unit borrowed from the 19th British Brigade, the 5th Scottish Rifles. During that long and worrying day Birdwood and Hobbs had repeatedly urged Major-General Wood of the 33rd British Division to retrieve the situation on his front, reiterating their concerns in a visit to his headquarters. Responding to this pressure — instigated, of course, by Pompey’s incisive reports — Wood approved Heriot-Maitland’s arrangements and told him (at 7.30pm that night) that the reinforcement units should advance ‘as soon as possible as the Australians were hard pressed on their right’.

The Scottish and Suffolk battalions had a challenging task. They had to move forward very much in the dark. Not only was it well past nightfall; the area they were entering was unfamiliar to them, and the location of the British and Germans within it was unknown. All the same, their rescue effort was lamentably mismanaged. Guides from 98th Brigade headquarters led them forward. The Scottish men followed their guide for over an hour before realising he was obviously lost — he had led them back to their start-point. Accordingly, there was no sign of them when the 4th Suffolk arrived at the joint pre-attack assembly point. The Suffolk commander proposed to move on without them, but Heriot-Maitland instructed him to wait. Two hours later he was still waiting. Just when he learned that Heriot-Maitland had changed his mind and directed the Suffolks to proceed on their own, a Scottish company belatedly arrived. There were further delays, occasioned by a thick mist hampering visibility, a sharp German bombardment, and uncertainty about the whereabouts of some Scottish companies. At one stage the Suffolks were poised to advance, but their commander told them to take cover because of enemy shellfire. In the end neither battalion managed to get into position to follow the British barrage forward, and they ended up 800 yards short of their objective.

Elliott was unaware of this sequence of events until shortly before the attack was to be launched, when a runner arrived at Hooge crater and handed over a message from Keith McDonald, Pompey’s liaison officer at 98th Brigade headquarters. It was the ‘intention’ of the British ‘to push forward quickly at zero and to get into touch with the barrage as soon as possible after zero’, McDonald reported, but three companies of the 98th’s left attacking battalion (the unit advancing next to Pompey’s brigade) had ‘lost their way’; hopefully ‘at least one company … will try to get as close to the original front line as possible’ by the time the Australians began advancing. After the assurances about the strenuous endeavours the 98th would be making, Pompey understandably concluded that its effort had been demonstrably inadequate. Suspecting the worst, he had already instructed Stewart to ‘be prepared to protect right flank of our attacking waves should British Battalions not make good their old line during the night’. But he recognised that the 59th, 29th, and 31st would just have to do their best without proper support on the right.

The support they received from the artillery, on the other hand, was outstanding. According to Bean, the barrage descending

at 5.50 on September 26th, just as the Polygon plateau became visible, was the most perfect that ever protected Australian troops. It seemed to break out, as almost every report emphasises, with a single crash. The ground was dry, and the shell-bursts raised a wall of dust and smoke which appeared almost to be solid. So dense was the cloud that individual bursts, except the white puffs of shrapnel above its near edge, could not be distinguished. Roaring, deafening, it rolled ahead of the troops ‘like a Gippsland bushfire’.

However, as the 29th and 31st Battalions moved forward with the 59th behind this superb barrage, a problem arising from their late inclusion soon emerged. The 59th, manoeuvring in precise accord with Elliott’s intentions and its previous training — a thin screen in front, and the following waves at appropriate distances behind — was disorganised by the determination of some 8th Brigade men to get forward as quickly as possible in order to avoid being hit by the inevitable retaliatory bombardment. The 59th’s orderly progress, then, was soon disrupted by the unexpected tendency of the 29th and 31st to push through it. Mason’s men also had to contend with resolute resistance from German defenders in a number of pillboxes.

At one of these pillboxes there was a critical encounter involving one of Pompey’s 7th Battalion originals. John Turnour, a theological student at Bendigo, had just turned 21 when the war began. He enlisted straightaway and became a private in Herbert Hunter’s Bendigo company, along with Noel Edwards and numerous other now-fallen comrades. Throughout the war he had remained in, and very attached to, that same company, transferring with a number of its members to the 59th, while collecting numerous wounds along the way. Now a lieutenant, he was looking forward to the honour of commanding this company for the first time at Polygon Wood when Elliott, aware of his record and propensity for getting hit, nominated him for a role in the nucleus. But Turnour protested to Mason, and Pompey reluctantly allowed him to participate in the operation.

With the attack held up by machine-gunners in a large pillbox, Turnour organised his men into various shell holes forming an approximate arc facing the pillbox, and told them to be ready to rush it. He then placed himself directly opposite the front of the pillbox (and the forward loophole the machine-gunners were firing through), stood up, waved his men forward, and charged. Although repeatedly hit, his determination and forward momentum carried him on until he fell, riddled with bullets, in front of the pillbox. By monopolising the defenders’ attention with such selfless gallantry, he enabled his men to rush the pillbox successfully. The bombers did their deadly work, and within seconds all resistance from the score of Germans in the pillbox ceased. Pompey later claimed that its capture, by creating a gap in the structure of mutually supporting pillboxes, paved the way for the encirclement and capture of others, and thereby contributed substantially to the 59th’s progress.

The Germans resisted sternly. Of the six officers who accompanied the two leading 59th companies forward, Turnour was one of five to be hit. Nevertheless Mason was able to report at 6.45am that his men were consolidating at their objective. Pompey, waiting and wondering back at Hooge, was delighted. Mason’s other news — no sign of the British on the right — was much less encouraging, if hardly a surprise.

This British failure soon became a major problem to Elliott when he realised that because of it the 8th Brigade battalions he had been given were refusing to push forward to their objectives on the blue line. Toll of the 31st was unequivocal. ‘Troops on right have not advanced. Am not advancing further’, he declared in a message that reached Elliott at 8.26am. Half an hour later a runner panted in to Hooge crater with a note from Mason confirming Toll’s refusal. Elliott referred the situation to Hobbs, who insisted that Toll had to push on as planned, while a flank barrage would provide the protection not forthcoming from the 98th Brigade. Pompey immediately informed Toll. A later joint message from the 31st and 29th stated that they had sustained few casualties in reaching the red line, and were ‘losing heavily from machine gun fire’ while remaining there, but they would be staying where they were rather than pressing on to the blue line because of the unprotected right flank. ‘Whatever justification Col. Toll may have had for failing to push forward’, Pompey concluded, ‘Col. Purser of the 29th had none’.

Elliott urged both units to get moving, an exhortation he reinforced when word came that the 14th Brigade on the left had reached their final objective (an accomplishment hindered by Purser’s reluctance to advance). ‘14th Brigade have secured their part of the blue line’, Pompey affirmed. ‘Push on at once and report progress’. Two hours later he had still heard nothing from the 29th or 31st to indicate that they had moved at all. Thoroughly frustrated, and having more confidence in his own brigade’s officers (a view which the morning’s events, from his perspective, seemed to have vindicated), Pompey directed Mason to tell Toll and Purser that they either had to get the 31st and 29th to advance or he (Mason) would have to supersede them, by order of the brigadier, and take charge of their battalions himself.

The situation on the right flank, as far as Pompey was concerned, ‘continued for some time to remain very obscure’. Retaliatory German shellfire after the launch of the attack had been ferocious. Downing was there:

The barrage continued without intermission for twenty-four hours, and what the men endured could never be described, for the effect of shell fire is horrifying out of all proportion to the number it mangles and kills. Each inch of ground was tossed and churned … a thousand times … the mangling, ripping thunderbolts crashed rapidly as a roll of kettle-drums.

The 57th company directed to advance behind the assault battalions and protect the right flank had been unable to do so because of this shellfire. But Stewart and Marshall arranged for the 60th further forward to assume this responsibility instead. Although little information about developments on the right was filtering back to Elliott, it was clear enough that the German penetration there was proving a substantial hindrance.

The meagre news that Pompey did have was hardly reassuring. Stewart reported that the ‘whole area is still being intensely shelled and any movement is most difficult’. There were fewer than 100 men left in the 58th, and his reserve had been reduced to one small company (Noad’s). The various companies and platoons he had assigned to the fierce combat on the flank were all now ‘lost to me’. Numerous runners and officers ‘sent forward have disappeared’.

Meanwhile the situation was being reshaped by an initiative from the 33rd Division. Major-General Wood, evidently also impatient with the 98th Brigade’s lack of progress, decided to detach a fresh battalion, the 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers, from his divisional reserve and send it forward — through ground gained by the Australians rather than his division’s fenestrated front — to make an advance south-eastwards from the 15th Brigade’s right flank. This attempt was scheduled for midday.

The 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers became one of the best-known battalions in the entire British army by virtue of the post-war literary accomplishments of some of its soldiers. A regular battalion with a proud history, the Welch had been involved in almost every significant British military engagement since 1689. The battalion was in France within a week of the outbreak of war in August 1914, and suffered severely at the Somme in 1916. Among its officers were Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon, who were to become acclaimed as two of the finest memoirists of the Great War; both wrote vividly and at times controversially about their service with the Welch. In very different style was Old Soldiers Never Die by Frank Richards, a fine account from a rank-and-file perspective by a Welsh ex-miner who served with the battalion in India and Burma before 1914 and continuously at the Western Front.

But the most outstanding memoir of all, especially from a historical viewpoint, was Captain James Dunn’s The War the Infantry Knew. Dunn, just like Pompey, followed years of university study with enlistment as a trooper in the Boer War and was awarded the DCM for gallantry in South Africa. In the Great War Dunn was regimental medical officer of the Welch (equivalent to George Elliott’s position in the 56th AIF Battalion) from November 1915 until May 1918, but was, as Graves affirmed, ‘far more than a doctor’. Tactically astute as well as exceptionally courageous, Dunn was not only frequently to be found in the firing line; he would often go out on patrol with the Welch and, Graves wrote, ‘became the right-hand man of three or four colonels in succession’. Richards was another Dunn admirer:

he was the bravest and coolest man under fire that I ever saw in France … I always thought he was more cut out for a general than a doctor and that he certainly would have made a better one than most of those who were.

The Welch came up via a long detour through AIF-captured territory. With their colonel away on leave, the acting commander was Major R.A. Poore, a 47-year-old stutterer whose DSO in the Boer War testified to his bravery. Having arrived shortly before midday at Black Watch Corner with the outstanding young pianist (and friend of Sassoon’s) who was temporarily his assistant adjutant, Poore discussed the situation with the Australians and then supervised the deployment of his platoons. The widely admired Welch adjutant was soon fatally wounded, two company commanders were hit, and the Germans managed to land one of their heaviest shells in a deep trench then occupied by Poore, the pianist, and another Welch officer they were conferring with, killing all three. The command vacuum was spontaneously filled by Dunn himself (a development unmentioned by the modest medico in his book). The Welch advanced valiantly, but encountered a hail of intense machine-gun fire that prevented them from reaching their objective — a cluster of pillboxes beyond Cameron House (and some 1400 yards east of Black Watch Corner) known as Cameron Covert. They managed to establish themselves at Jerk House but not Cameron House, which was ‘desperately defended’, Elliott pointed out, and ‘a formidable obstacle to the advance’:

It was on a slight eminence giving excellent fire command in all directions and although at times our men and the Royal Welsh Fusiliers were on three sides of it, it could neither be approached or silenced owing to the fact that the “Pill Boxes” in Cameron Covert effectively protected its flanks and rear.

Frank Richards, stationed for most of the afternoon near Black Watch Corner, was well and truly back in what he called ‘the blood tub’:

The ground rocked and heaved with the bursting shells. The enemy were doing their best to obliterate the strong point that they had lost … a dud shell landed clean in the trench, killing the man behind me, and burying itself in the side of the trench by me … It was … the first time I had been in action with the Australians and I found them very brave men. There was also an excellent spirit of comradeship between officers and men.

Richards knew he was fortunate to have survived such a fierce and prolonged bombardment:

Not one of us had hardly moved a yard for some hours, but we had been lucky in our part of the trench, having only two casualties. In two other parts of the strong point every man had been killed or wounded.

Not far away Dunn was trying to compile a brief report for Heriot-Maitland, but the ‘writing was interrupted several times by the quantity of soil that was thrown about us’.

Information from a prisoner indicating that an enemy attack was imminent seemed confirmed when hundreds of advancing Germans came into view beyond Cameron Covert. Seeking a stronger defensive position in response, the acting commander of the most advanced Welch company authorised his men to fall back to Jerk House. Many withdrew further. Onlooking Australians, angered by this excessive voluntary retirement, remonstrated vehemently with the back-pedallers; some even halted retiring Welch parties by threatening to shoot them. A 59th lieutenant who did so was later thanked by two apologetic British captains who were embarrassed about this unforced withdrawal. (One of them might have been Dunn; Richards saw him stop some Welch who were falling back.) In fact, this German attack foundered before it really began, thanks to timely artillery intervention.

But General Wood, the British divisional commander, was increasingly frustrated by the lack of progress on his front and its impact on the whole operation. Striving once again to invigorate the 98th Brigade, Wood directed Heriot-Maitland to ‘make every endeavour to advance to the blue line’; it was ‘of utmost importance that right flank of Australians should be covered by you’. But Plumer had already given up on the 33rd Division. The Commander-in-Chief approved his proposal that a fresh division should be transferred to his army ‘in order to complete the work which the 33rd Division had not been able to carry out’.

Progress was much more satisfactory on the left of the 15th Brigade front. Stan Neale, an ex-7th Battalion veteran now a captain in the 59th, was particularly prominent, rallying the retiring Welch and ensuring that his battalion reached the correct objective (some Australians had halted prematurely, believing they were on the red line). Shortly afterwards a spontaneous manoeuvre by 59th men dealing with counter-attacking Germans brought them forward almost to the final objective, an advance which made the 29th’s task of consolidation on the blue line relatively straightforward.

Pompey, then, was free to concentrate on expediting progress on the right. It was time, he decided, to use Marshall in a more offensive capacity. The 60th colonel had been busy supporting the 59th and 31st Battalions: he had been supervising the provision of reinforcements and supplies, the care of the wounded, and the safeguarding as much as possible of the right flank as the advance progressed. Liberating Marshall from these responsibilities at dusk on 26 September, Elliott directed him to organise an attack towards the main stumbling block on the right, Cameron House. With units considerably scattered and intermixed, Marshall initiated reorganisation and patrolling. About midnight he and Stillman inspected an advanced position held by Australians in the British sector. From there Marshall decided to reconnoitre further forward with Stillman and a small party. After venturing over 100 yards, they discerned a pillbox up ahead. Marshall proposed a raid. His companions agreed to give it a fly. They succeeded — the pillbox and those of its occupants who survived the skirmish were captured. Marshall arranged for the Australian line to be brought forward to this strongpoint, then led his party on further.

For some time Marshall remained unaware that the pillbox he had just acquired and failed to recognise in the dark was the very heart of Cameron House. He informed Elliott merely that he had captured a pillbox and a few prisoners, adding that he was still probably hundreds of yards short of Cameron House. Of Marshall’s subsequent adventures as he proceeded towards Cameron Covert, Pompey knew nothing. A separate patrol was sent out to clarify the situation on the right; its report that Cameron House was in Australian hands left Pompey puzzled. When the sketchy information reaching Hooge crater (as Street noted) ‘continued to be somewhat contradictory’, Pompey decided at dawn on 27 September to resolve the uncertainty by going forward to see for himself. Peck, alarmed by the risks involved, tried to dissuade him, but Pompey was insistent.

Grimly purposeful, he was accompanied on this front-line visit (as in similar circumstances at Fromelles) by Schroder. On their way forward they came across an unwounded 15th Brigade officer in what Pompey concluded were suspicious circumstances. ‘Your men are up there fighting for their lives — what are you doing?’ he challenged accusingly, threatening to shoot this officer for dereliction of duty, before allowing himself to be persuaded by Schroder that such on-the-spot punishment might be a trifle hasty. They pressed on, passing Stewart’s headquarters pillbox (and presumably startling the occupants) about seven o’clock. Fortunately the German shellfire had died down and things were relatively quiet by the time Elliott reached the front line and began an extensive inspection. Schroder remembered it well:

with mud and slush up to our knees, Pomp took short cuts and missed nothing. The boys who looked abjectly miserable when we arrived at the various pillboxes and shell holes managed to raise a grin when the old man spoke to them.

Elliott’s appearance so far forward amazed the Welch. ‘It was the only time during the whole of the war that I saw a brigadier with the first line of attacking troops’, marvelled Richards. Dunn was stunned. Having lamented earlier in his book that it was ‘rare for anyone who combines authority and nous to be on the spot’, he described a brief conversation ‘the Australian Brigadier … called “Pompey” by his men’ had with two Welch officers: ‘He told them that there were few, if any, Germans in front of our position, he had “been to look”’. That a general would undertake such intrepid personal reconnaissance was a revelation to Dunn, who was also impressed to find the AIF colonel in charge of medical arrangements well forward: ‘Was one of ours ever within the shelled zone when there was the greatest need for him to know how things were being done, and what might be needed?’

Pompey’s comprehensive front-line inspection was crucial to the outcome of the battle. The morale-boosting, invigorating effects of his visit were considerable, but the tactical initiatives arising from it were even more significant. His first impressions were dominated by the chaos of the battlefield. ‘I never saw such a scene of confusion, men of all regiments mixed up all over the place, dead of all regiments lay aside the enemy everywhere’. But he quickly discerned that a sweeping success was within reach, and some well-placed pressure could achieve it.

I arranged with Marshall to consolidate Cameron House and the wood called Cameron Covert … Urged on the Welsh officers who still survived to reorganise their men. Ordered Mason to push forward to the junction of Cameron Covert and Polygon Wood and consolidate along the eastern edge of the Polygon Wood which runs northwards from there. I found Col. Toll of the 31st and Col. Purser of the 29th Bn in a dugout. The former I sent to reorganise his Bn which was much disorganised in Polygon Wood and to lead them forward to the blue line. Col. Purser I sent to establish a HQs with his Battn in their area and to make a report on the situation there. I then returned to [my] HQs and made a full report to Division. Shortly afterwards received the gratifying intelligence that Toll had made good the blue line and Marshall strongly established in Cameron Covert. In the afternoon we further got word that the British had now pushed right in and got the remainder of the blue line. This was in consequence of my report on the situation.

Essentially, Marshall and his men (assisted by the 15th Brigade’s Stokes mortars) had pushed forward on the morning of 27 September in the British sector in and around Cameron Covert until they were beyond the final objective. This assisted the 31st Battalion to advance on Marshall’s left in order to link up on the blue line with the 29th; it also facilitated an afternoon advance by the Welch and other British units to plug the gap on Marshall’s right. The Germans unleashed a furious retaliatory bombardment — ‘the heaviest I have ever known’, wrote a 58th lieutenant — but it eventually eased, and the 15th Brigade was withdrawn that night. Marshall handed over a frontage of 250 yards in the 98th Brigade’s area.

It was an outstanding achievement by Elliott and his men. All objectives were attained, and the victory was won in circumstances of the gravest adversity. Despite the units engaged becoming unusually intermixed, the 15th Brigade had demonstrated admirable cohesion. Among the participants in Marshall’s exploits at and beyond Cameron House were lieutenants from the 57th and 58th as well as his own officers. At one stage Noad was in charge of a party comprising men of the 57th, 59th, 60th, 31st, and Welch Battalions. And Mason’s glowing praise for the officers from other units, who enabled the 59th to move into position so smoothly before the attack, was matched by his commendation of the assistance he was given during the battle by the 58th’s leaders, notably Majors Freeman and de Ravin (another original 7th officer to join Pompey’s brigade). The victory was also a personal triumph for Elliott. Under his leadership, Bean concluded,

the 15th Brigade and the troops reinforcing it snatched complete success from an almost desperate situation on the right … His staunchness and vehemence, and power of instilling those qualities into his troops, had turned his brigade into a magnificently effective instrument; and the driving force of this stout-hearted leader in his inferno at Hooge throughout the two critical days was in a large measure responsible for this victory.

Elliott’s leadership was all the more outstanding in the circumstances, because he had to cope with devastating news unrelated to his command while the battle was raging. During the advance by the 14th Brigade on his left, as he learned at around 3.00pm on 26 September, his brother George had been mortally wounded. George was in Chateau Wood, only a few hundred yards from Hooge crater, waiting to go forward with the 56th Battalion when

a fragment of a shell struck him on the back of the head crushing his skull and he died a few hours later without regaining consciousness at all. They brought the news to me when I was tied to my office directing the fight and I could not go to him though they said he was dying. I hope never to have such an experience again. The effort to concentrate my thoughts on the task of defeating the enemy as the messages came through revealing each move and the changing phases of the battle to me seemed as time went on to turn me into stone and half the time I was like a man sleepwalking, yet I do not think I made a single error that I would not have made at [training] manoeuvres under similar circumstances.

George’s death was bad enough, but during the battle Pompey also received appalling news from home. A letter arrived from his friend Charles Lowe, a barrister who had been a university contemporary and was to become one of Victoria’s longest-serving and most respected judges. This letter informed Elliott that his legal partner since 1909, Glen Roberts, had involved their firm in dubious speculations and amassed huge losses in his absence, with the result that Elliott had become, he learned, liable for debts amounting to thousands of pounds. This was a disastrous turn of events, all the more devastating because Elliott was committed to an upright code of honour and morality, and struggled to suppress a sense of personal financial insecurity (although he had less need than most to worry, thanks to his father’s estate). Moreover, his absolute adherence to financial probity was reinforced by his perception that spotless integrity was essential to his future as a solicitor. Now more than ever he had to summon all his willpower to maintain his focus on the unfolding battle. The unpalatable task of telling him the facts had evidently not been rushed; Lieutenant Len Stillman had known of his uncle’s financial disgrace for at least a month.

After the exhausted remnants of his brigade were replaced in the line, Elliott had one last task to supervise before he could begin to unwind:

I had made arrangements for the removal of my brother’s body, and at noon or shortly after we buried him with military honours in the little military cemetery to the west of Dickebusch. And so our battle came to an end. I was so utterly weary of body and soul at this time that neither shells, bombs or gas had the slightest terrors for me. In fact I was more like a man in a trance whose power of sensation had for the time being [been] removed. After a sleep I felt better.

During the next few days his headquarters was inundated with congratulations for his brigade’s outstanding feat. Birdwood and Hobbs both called to offer theirs personally. Plumer went so far as to thank Elliott for saving the British army from disaster. Prouder of his men than ever, Pompey described the 58th as his ‘Stonewall Battalion’, and assured its survivors that their stand on 25 September would become a military history classic. Reviewing the battle with his officers and men, he emphasised the importance of compiling detailed accounts of the fighting in order to produce an incontrovertible record of what the brigade had accomplished.

Not surprisingly, his men were more intent on resting and counting their blessings to have survived. Keith Doig, writing to his fiancée on the day his friend George Elliott was buried, admitted he ‘had never been nearer death’:

crouched in a shell hole with the big shells dropping all around me, I felt quite resigned and just wondered where the shell would hit me … I was blown off my feet three or four times, I was covered with earth thrown up by the shells, I was hit with small fragments, yet marvellous to say I came out unscathed.

‘The Somme was bad, Bullecourt was worse, but this place beats all’, Doig concluded. Brigade casualties (around 1200, with another 720 in the 8th Brigade units) proved to be ‘heavy’, Street noted, ‘but not greatly so when the fierce nature of the fighting is taken into consideration’.

One particular casualty was preoccupying Pompey when he began his first letter to his family five days after the battle. ‘I am very sad still’, he told Kate:

Poor old Geordie, I saw him dead so white and rigid and still and his loved ones left behind him. And we have buried him so far from home amongst strangers to him. I am so glad I was able to bring his body back from the shell torn zone to a little cemetery where the grass was smooth and green and we fired the volley over his head and laid him in the grave with the Union Jack flying over him and our great guns still roaring in the distance. Poor Lyn and poor little darling Jacquelyn. You must tell our bairnies to love them both well. Tell the little people that the horrid old Germans came on in thousands to kill Dida and his soldiers because we broke their wall down and tried to catch them all, and … near Dida the Germans hit poor old Uncle Geordie with a shell and he died and has gone away to Heaven and we will not see him any more until we die too and go to Heaven and dear little Jacquelyn will never see her very own Dida at all … then Dida’s own soldiers got up and they chased those nasty old Germans back for a long way through the bush that is called woods here and they caught and killed such a lot of them and those that weren’t killed … have been sent away to jail again.

The stirring account of the battle that followed underlined his pride in his brigade. ‘We have had a wonderful battle and a wonderful victory’, he wrote. ‘My boys have simply covered themselves with glory’. He was frank about his reaction when his forceful recommendation to postpone the operation was rejected, and he then had to reorganise the attack with most of the ammunition stockpiled for it unavailable, the newly allocated 8th Brigade battalions unfamiliar with the ground, the enemy barrage still unimaginably severe, and the neighbouring British unable to deal with the enemy incursion on their front. ‘I felt appalled at the task’, he admitted, but his officers and men had responded superbly:

Many many have fallen but we have in the fight stamped our fame on a higher pinnacle than ever … It is wonderful the loyalty and bravery that is shown — their absolute confidence in me is touching — I can order them to take on the most hopeless looking jobs, and they throw their hearts and souls not to speak of their lives and bodies into the job without thought.

Then there was the Roberts business. ‘Oh Katie’, he added, ‘as if my other troubles were not enough’. He described how he had been grappling with the complexities of the battle when a letter arrived with shattering news of his partner’s debts.

I am sorry for poor Mrs Roberts. God help her. Try not to worry darling. It is a bitter blow to me as I fear the money coming from my father’s estate at mother’s death, which I was hoping would provide for the children should anything happen to me, will be taken from me for the creditors. I can conceive no more mean trick than this played on a man in my position. I think I could have the villain put in jail but it would only cause a scandal and probably ruin the business without releasing me from debt in the slightest.

He explained that he had arranged for Lowe and J.W. Begg, a lawyer from Moule’s (where Elliott had done his articles a decade earlier), to extricate him from the mess on the least disadvantageous terms they could manage.

Elliott did not conceal from Kate that the combined impact of these two blows while he was already under immense strain was almost unbearable:

I cannot tell you what I went through that night … After I knew Geordie had died I would have gladly welcomed a shell to end me. I walked twice from end to end of our zone and along the front line in front of the enemy’s machine guns and never a shot came near me. It may be your prayers that protected me.

Also shaping this reaction was a ‘feeling now amongst some of us that we have so many friends true and tried on yonder shore awaiting us that we should be more at home there than here’, as he told George McCrae (whose son he had very much in mind when writing this). Pompey ‘felt almost guilty of disloyalty to them in being still alive and not accompanying them to the unknown’.

He wrote again to Kate the following day.

I got today from the Ambulance people poor Geordie’s watch, cigarette case and a few things he carried on his body, also the shoulder straps with the stars from his coat which I had cut off as a last memento for poor Lyn … I feel still very sad and depressed. It is terrible to think of him dead, poor boy, one can hardly believe it. If I had not seen him dead and helped bury him I doubt if I could have realised it … It is very bitter too to think of what Mr Roberts has done to us … I think this is just about all for the present. I am too heartsore to write much.

Although he did not feel like writing amid all this torment, he was sufficiently perturbed by something Kate mentioned to scrawl a hasty separate note to Neil:

My dear little laddie, Mum has been telling me that you were so sorry for being naughty that you wished you were a little girl like [Violet]. But if you ever changed to a little girl Dida and Mum would not have any little boy at all. And Mum and Dida would be dreadfully sad if they had no dear wee mischiefy thing like our laddie. Dear little chap, Mum and Dida love you so much that they don’t mind very much when you are naughty. Of course Mum has to [scold] you because if she didn’t you wouldn’t know what was naughty and wrong to do … Dida was sad when he heard that the little lad wanted to be changed to a girl. He loves his little laddie so much that he was sorry the poor little chap was not happy. So don’t you worry a bit old chap. You just try your best to be good and if you forget sometimes and Mum has to spank you, just be a soldier and try not to cry very much and you will know that Mum and Dida love you just the same even when they spank you. Spanking isn’t so bad if you feel quite sure that dear old Mum loves you just the same. Dear little laddie, I wish I was with you now to take you up on my knee and comfort you and tell you Mum and Dida will always love you. You must be very good and loving now to dear Lyn and dear little Jacquelyn because dear Uncle Geordie their Dida was killed by the beastly old Kaiser’s soldiers … You must love and help dear old Mum and Belle and Nana very much too and cheer them such a lot. If you love them a lot that will cheer them.

The third battle in the AIF’s step-by-step operations east of Ypres, the advance to Broodseinde Ridge on 4 October, was another decisive victory. The bite and hold approach was clearly proving successful, but Haig’s keenness to pursue it even after the weather deteriorated led to the ill-advised assaults that made Passchendaele notorious. The turnaround was attributable to ‘the vile weather and the awful mud and the over optimistic opinions of our Higher Command who thought the Bosche were on the run’, explained Pompey, relieved that his brigade was uninvolved in such dreadful enterprises. He was appalled to hear of attacks so ill-conceived that heavy losses ensued ‘simply because the men got stuck in the mud and the Germans picked them off at their leisure’.