If you’ve ever walked down the street, seen a name, and wondered what that marking meant, I’ll tell you: It means somebody is telling you a story about who they are and what they are prepared to do to make you aware of it. Every time a name is written, a story gets told. It’s a short story: “I was here.” Who is telling it and where they are telling it will determine how the story ends. Some stories will be adventures, some tragedies, and some courtroom depositions. But every single one has a star, a stage, and an audience, and that’s all a growing youth needs to have fun.

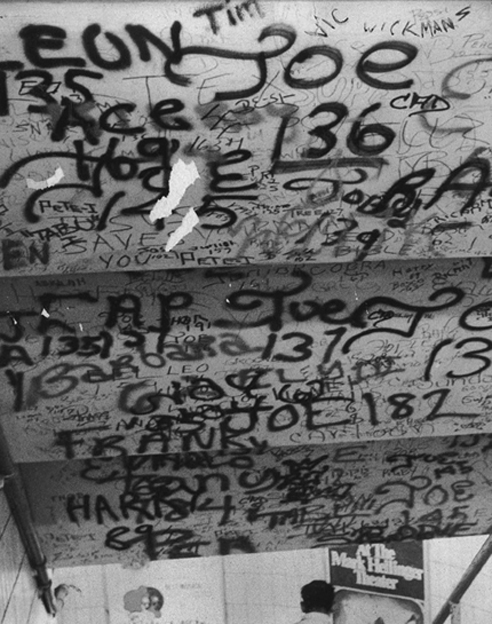

Graffiti is about thirty years old, give or take a year. It’s impossible to pinpoint because, in spite of its detractors’ fury, spray paint is hardly a permanent medium. Thanks to a dedicated sun, most graffiti fades over time. What the sun misses, a vigilant brush gets, so graffiti lives on in only two ways; the photo and the story. Both of these methods, are, in their own way, imperfect. That’s what makes the story of this expression so difficult to tell, and so compelling to hear. Photos are typically snapped, developed, divided up, and traded with others. What remains is stored in a shoe box. It seems every writer has one, and they all have a complete disregard for organization. There’s something very fresh about that, though. Graffiti is about doing it, being it, and getting it. Proper documentation has, until recently, been the furthest thing from the writers’ minds. And ironically, the most dedicated archivists of the expression are not even writers. So true graffiti lives in the moment, and while every mark a writer makes will probably get buffed or fall into the hands of someone who’s missing a lot of details, at least we’ve got the stories.

Stories are the most permanent medium for storing and sharing the graffiti experience. While photos are hidden and only brought out to show a few intimates, stories are readily exchanged, embroidered upon, and passed on again. The real story of graffiti is necessarily an oral history. Good stories go across the world in minutes and last forever. It’s not just the writers, it’s the cops and the anti-grafftiti activists too. Everybody loves to tell you a good graffiti story. The story gets darker and more visible with each retelling and it can’t be painted over.

No one person better illustrates this than KAP. He was a Philadelphia writer who constructed his own myth. He called himself “the Bicentennial Kid,” and in 1976 set out on a course to ensure his name would be remembered. He wrote on everything, but it was a print on the Liberty Bell two weeks before the big Fourth of July celebration that ensured his immortality. Mayor Rizzo personally offered to break his fingers, which, as any Philly writer will tell you, was a gold-medal moment. KAP died of leukemia in November of that year. But then he’s still here, isn’t he?

This book is for everyone with a good story. This book is for the ones that I didn’t get to tell. This book is for the ones with no story of their own yet. I hope everyone gets heard, word.