Suroc rolled on to my block with all the fanfare of the ice cream truck. Kids ran off porches to meet him, but clutched in their hands were sketches, not money. He dissed every youth in a good natured way, letting just a tiny glimpse of encouragement sneak past his tough-kid facade. I couldn’t even bring my blackbook out of my jacket. I didn’t need to hear that I was wack, and he was mid-tirade any way. Some dissed toys were trying antagonize Suroc by pumping up a writer from the next neighborhood. Suroc wasn’t having it, “That guy is a bookworm, he doesn’t walk routes, he doesn’t have any roofs running, he’s only up on his refrigerator.” All the toys stifled themselves so Suroc spun and walked off the block. “Damn”, I thought, “that’s the way to handle it.” I told him what I wrote and I asked him, “What’s a good spot to hit?” He told me, “The waterfront, but it’s real hot right now.” He scratched himself through his Op shorts and said, “Whatchu write?” I stammered, not trying to tell him twice, “I’m gonna try to do something.” He shrugged his shoulders and kept stepping.

That whole scene was classic Suroc. The 6-4 Posse (this is a gang, and I’m in it) called him “Hollywood” because he was so good at being conceited. He had a great resume to back up all that snapping; 70-80 pieces, some roofs, some routes, and really dope black book pieces. He started writing at 12, and two years later in 1982, Print Magazine featured a spread on Henry Chalfant’s photographs. The pictures leapt off the page and into his imagination Graffiti was taking its first steps from localized to worldwide phenomenon, and Suroc was one of the first locals on the train. When I met him in 1985, the post-Style Wars / Subway Art explosion had taken hold, so everybody was down for a quick minute, and the 17-year old in the matching Guess jacket and jean set was the Krown Ruler. In Philly anyway. (Just like the Krown Rulers rap crew never blew up anywhere except Philly.)

The history of name murals in Philly can be summed up very quickly: It was mostly prints, that is stylized signatures, until the mid-70’s when John Ski, Pretty Boy, Kap, Mango, Billy Dab, and Sir Nose started painting what the print writers derisively called “New Yorkers”, on the El Trains and in the streets. These guys were bombers that would do the fancy stuff only when time permitted. Then Estro set a new standard. His joints were easy to read, but impeccably designed and beautifully colored. He would paint characters and drop a punch line next to it too. He was a complete original. He was also the first “art school” writer, attending classes in the day time, doing pieces at night. He was part of the era of Razz, Sub, Clyde, Mr. Blint, Pizazz, and Credit, who were all walking routes and painting pieces with equal fervor. In doing so won respect from the older writers.

MB took what they did and infused with contemporary NYC technique. MB was a political machine too. He had the city wired his way, and rained shit on the competiton for a while. Suroc broke through about the time MB had cemented his hold on the scene. First he mastered Dondi’s style, then just as quick flipped it into an original style based partially on Philly print letter forms, and partially on a rigid, yet flowing style he developed all by himself (well, maybe there was a little Flite TDS in there). By 1983, he was the style king of Philly. MB, however, not ready to relinquish the title, had about 20 of his pieces rubbed out, including one an hour after he finished it. By 1984 Suroc was an exile in his own town, and spent a good deal of his time painting the one thing that he knew wouldn’t get dissed – freights. He stopped because he thought it was like throwing a bottle into the ocean with no idea who, if anybody, would see it.

Of course, Lots of kids saw the future in painting freights, but we’re not here to dwell on that, it’s about how he put me on a good track that I’m rolling on to this day. The first thing he taught me was, “I’m not gonna show you anything.” At first I thought it was to discourage me from sweating him, but he thought graffiti is best learned by intuition and biting. I spent a long time copying pieces out of Subway Art until Suroc agreed to answer a few questions I had about letter structure. I wanted to know if the shape of a piece was more important than the actual letters. He didn’t answer, he drew an outline on a sheet of looseleaf and I can recall to this day how the letters erupted out of the pen to form a cohesive whole that looked like nothing I had seen before. “I don’t know,” he said finally, “if it looks right, you did it right.” After a few more weeks it was clear that I was going to get a rep with or without him, so Suroc started taking me to spots to paint. Our first stop was a rooftop facing the el that we accessed by scaling two walls, two stories high and 3 feet apart in a breeze-way. My debut piece with my local hero was pretty Sab-and-Kaze-like, but I flipped it enough that instead of a shark with a shotgun that their famous wholecar was adorned with, I rocked a fish with an uzi. I was learning another, much older lesson than me or Suroc: Bad artists copy, good artists steal. I was a klepto of a higher caliber than that gun that fish was holding, for sure.

After a few months of running with him, I had learned a lot of the rudiments of writing, but he also instilled a philosophy he called, “Graffiti Ergo Sum”. Loosely translated, it means, “I write, therefore I am”. It was the distillation of a lot of thought he put into this most infantile of mediums, researching modern art history thoroughly, and understood before he got out of high school why Duchamp and Heartsfield were important to his expression. With Duchamp it was the way he assumed alter egos to project his visions onto outraged critics. In doing so Duchamp upended the perception of what was considered art and who was considered an artist. With Heartsfeld it was the way he used photomontage and collage to criticize the Nazi regime of his native Germany eloquently and effectively. Somewhere between these twin towers he set up shop, and began to explore the distances graffiti could cover in his own world.

My world was still in the street, where crack was making its presence felt on every front. One week the writers at the meeting were talking about who had more spots, the next week they were arguing over who pushed more rock. Suroc rolled his eyes and retreated for a time into the stronghold of imagination, an 8 and 1/2’’ X 11’’ fortress of attitude. The blackbook that used to just be a showroom now became a laboratory. Fully blended Design Marker masterpieces were now replaced with sketches, color studies, theories, plans, candy wrapper logos, and xeroxes of art texts with highlighted quotes. Conviced of the lack of worth in the turf the competition was fighting over, he set his sights on a new line to conquer; The blackbook became a battle plan for the takeover of popular culture.

Blackbooks have been around since leather trenchcoats and turtlenecks. In Philly they were happy with composition books, but with the advent of the style wars, everybody soon got with the now-familiar hard cover sketch books. In Philly they were always a fashion accessory more than anything else, but a few people had a reputation for using them correctly, including Spel, Share, Cee 67, Dazer, Lover, Skim, Prink, and Teaz. I’m sure there were others, but those were the ones I wanted to bless my book in 1986. At the time, they were simply doing standard pieces and characters. While Suroc was taking his blackbook in another direction entirely, trying to build a ramp from the low art back road of graffiti and the High Art highway that seemed to run parallel at points, yet never connected.

Suroc had a lot of great ideas about the directions graff could go, but before he could go far on that train of thought, he caught an 11,000 volt bad one on the tracks. Good luck and a good samaritan got him to the hospital in time to find out that he had burns over 30% of his body, 10% of them were 3rd degree, and he was lucky to be breathing. Suroc endured a long recuperation, made easier by the fact that he was in good physical shape when he got hurt. He never stopped writing graff, it just kept getting different as his life changed. He was true to the artist he wanted to be by having his graffiti keep reflecting his life. True writer that he was he did it with letters and colors. That blackbook stayed with him every step of the way reflecting his highs and lows as he regained his health. The first thing he did when he got better was go into the army. Somehow he bogarted his way into Special Forces, which anyone would expect from a hustler like himself. He jumped out of airplanes and shed the fear that had only hung around him since he got burned. In his free time, he painted pieces on tobacco sheds in the area around the base. He came home with a wife and a kid in tow and moved to Jersey. He was the first writer I saw successfully grow up, and that’s enough.

I was more than happy to push ahead and realize a lot of the ideas he had, to test the theories he proposed, and become a high art vandal in a way that responsibility and real-life would not let him. I went to New York and painted in ways that the graff mecca never saw before. I blended snaps and wisecracks with pop art. I paint intimate signs and booming blockbusters. I work as hard on tags and pieces as I do on paintings and studio works. Everything I do has a trace of Suroc in the mix. It’s hard to find any student of a good teacher in any field that doesn’t carry their influence into every work. I go home again and again, and show him the work I’m into. He takes as much pride and more than I do, and I’m happy that I don’t have to explain any of it.

Epilogue: That blackbook is still close to him, in it he draws pieces of his own life, seen through a pop kaleidoscope. In the margins he distills a philosophy of graffiti that goes far beyond the current semantics of fame all the way to a personal mode of expression. The book will keep mutating, reflecting the continual growth of his ideas through a medium he discovered almost 20 years ago, and made his own 12 years ago. Looking back, most of the class of ′80 got diverted into hard times, hard crime, or just flat lined. There’s just a few who stuck to it, and a fraction of those who use it to dialogue about who they are, where they are. It is a small school of thought, and he’s the dean of graffology, Philly campus. If you can stand it, a degree can be yours in just 144 short months.

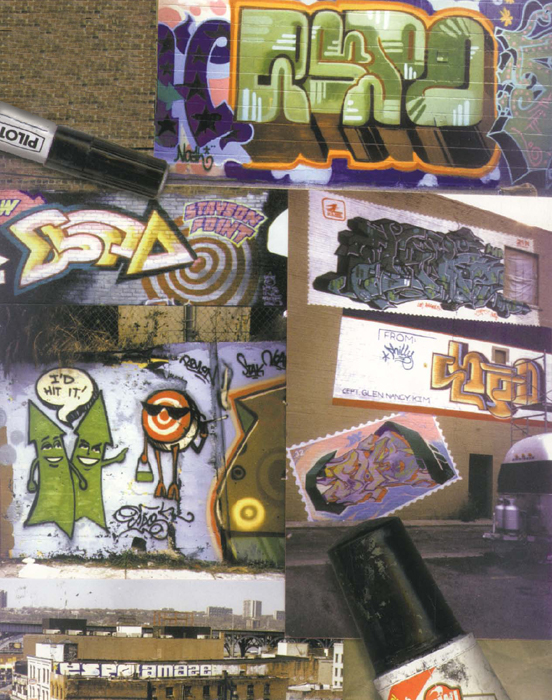

Fourteen years of evolution in three easy steps. 1) Reading from the NY script with a NOCing character, 1984 (upper left corner).

2) Above the crowd with his own style, April 1987 (middle left).

3) Good tidings from the pop life, 1995 (lower left corner).

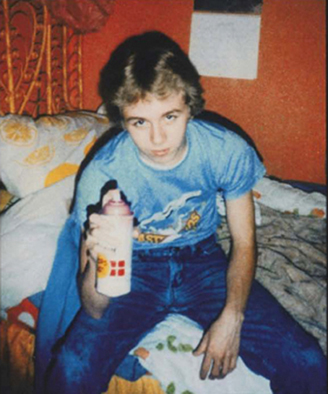

The father of Freights? Well, BRAZE can pass out cigars too. Up top, Suroc with AB 63. ICY KINGS by MAT, STEVE, SUROC and METRO aka DAZER. SUROC lamping. SUROC laughing, possibly at the tight shorts he’s wearing. All four from September, 1984 (from upper right to lower right).

MB, half-hero, half tragedy, all city king. He was a master of pieces, handstyles, and competition. He was completely dedicated to both destruction and design. By walking routes endlessly and painting the best pieces in the city, he was impossible to beat on any level, and he relished winning. In the end, the only writer that beat him was him, getting distracted by the dumb shit for damn near a decade. Today he’s reportedly saved and happy, and I’m not mad at that. Even as a wild juvenile, he knew Rusto had the gusto.

A Passion for fashion in Frankford gets a thumbs up.

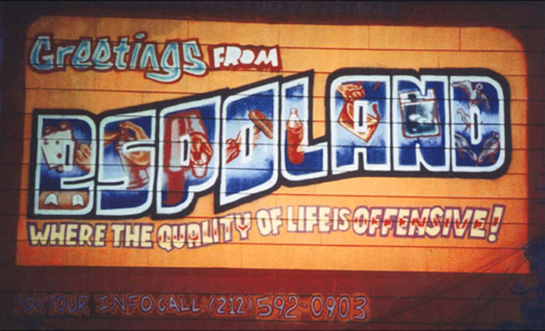

West Side Highway Story: I’m in the home stretch with no hassles, when I hear a police radio squawk. I nearly fall off the ladder, but keep composed when the cop on the beat asks, “What do you get paid for this?” I said, “$17.50 an hour, plus overtime”. He nodded and walked on. The check is still in the mail. Dec. 20-23, 1997.

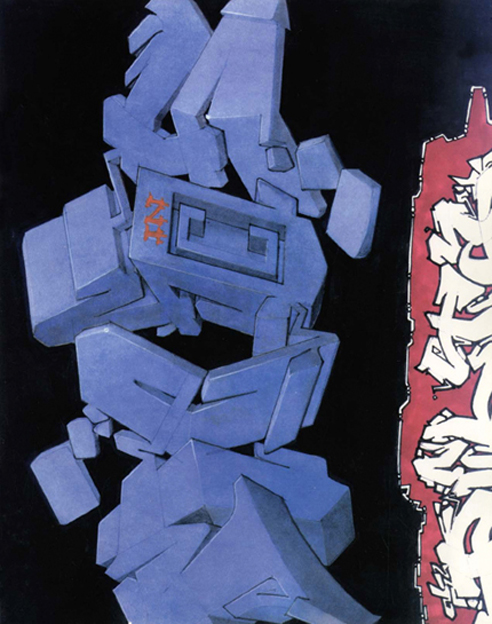

This piece was drawn from the FBI sketch of the UNABOMBER a week before he was captured and revealed to barely resemble the rendering. Ironically, it’s in the FREEDOM tunnel, 1996.

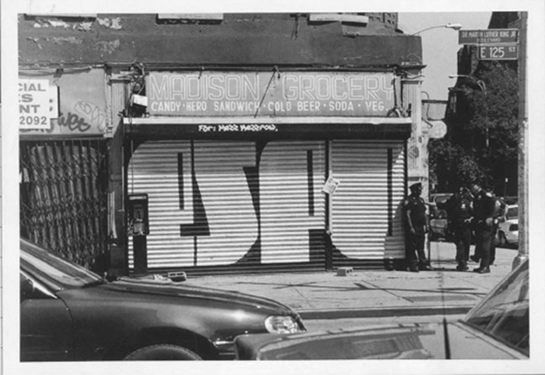

THE LEGAL EAGLE HAS LANDED: Clockwise from right: Philly 1998, Toronto with Tyke and sub 1997, San Francisco 1998, 125th and Broadway 1996, and BOSE’s backyard 1995. Can I kick it? “Yes you sprayCAN”.

FLATBUSH. 1995 The piece flipped and ratted out the sketch. The sketch pled guilty, got probation and later his record was erased.

SMITH: “You know you can fill in a piece with bucket paint.” ME: “Oh wooorrrdd?” 22nd and JFK 1990.

Queens, AOK after-effect. Crazy shout out to Rick Griffin.

See you at Scribble Jam! Cincinatti Ohio, 1997.