INTRODUCTION

The Shoninki

Lay before you in these pages are the deepest secrets of the ninja. The ancient scroll translated here is the Shoninki (正忍記)—a true shinobi account and one of three ninja scrolls from a samurai warfare school known as Natori-Ryu (名取流). The term shinobi or shinobi no mono is the correct way of saying ninja in medieval Japanese. The scroll was written by the samurai Natori Sanjuro Masazumi (名取三十郎正澄), who was known to his peers as Issui Sensei and was a warrior who served Lord Tokugawa Yorinobu as a close retainer and warfare specialist in the city of Wakayama, Japan. The Shoninki is only one of approximately 30 manuals that make up the Natori School of samurai warfare, and is the final ninja scroll of the whole curriculum. A student of Natori-Ryu is expected to have studied the main scrolls before they arrive at the secret teachings of the shinobi, thus the Shoninki is written from the perspective that the student has a full knowledge of samurai warfare and the details of Natori-Ryu. Therefore, as a modern reader, understand that while this manual may seem vague in parts or lacking in specifics, it was written for warriors who could fill in the gaps though years of mastery in samurai ways. Therefore this scroll should be seen as a final “conversation” between Natori Masazumi himself and his students, giving them a full understanding of the ways of the ninja.

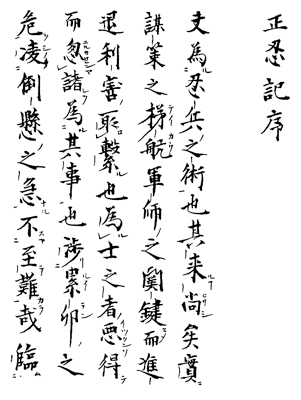

The first page of the Shoninki from the transcription in the National Diet Library

The Shoninki was written in 1681 and was kept as a secret document available only to the most ardent students—it was not meant for public dissemination and it was not until the early twentieth century that it was first published, at which point it formed the foundation for Japanese research into the lost identity of the shinobi warrior. Over the past century it has been hailed as one of, if not the finest examples of shinobi literature, because unlike the majority of ninja scrolls, it is fully explicit on the teachings. It does not aim to hide anything, nor is it simply a memorandum list—a common trait of shinobi manuals. Furthermore, it is considered as kuden (the full oral tradition) for the manuals that precede it, that is the scrolls named: Shinobi no Maki and Dakko Shinobi no Maki, all three together create the Natori-Ryu ninja arts. The original Shoninki is currently missing and only a few transcriptions exist. In the main, most people are aware of and use the Natori Hyozaemon transcription of 1743, which can be found in the Japanese National Diet Library (catalogue number: 214–9).

The shinobi of Japan are a worldwide icon, a household name and one of Japan’s most popular cultural assets, and the Shoninki is one of the premier representations of the historical ninja. The manual is deceptively deep and written so that with each reading, more lessons are found, and avenues that you did not see before open up. Thus, treasure this collection of ancient teachings and enjoy your journey into the world of the infamous ninja.

The Arts of the Ninja

The arts of the ninja are collectively known to the modern world as “ninjutsu” (忍術), but they should correctly be termed “shinobi no jutsu” (の術)—literally, “shinobi skills.” Shinobi no jutsu itself is not a complete system for a warrior; instead, it is an auxiliary art, a skill set that is attached to a warrior’s military training. Samurai and ashigaru (foot soldiers) would be trained in multiple aspects of warfare, including some or all of the following; armor and equipment, weapons handling, unarmed combat, horse riding, formations, troop maneuvres, military tactics, warfare skills, esoteric rituals, encampment rules, scouting, incendiary training and Chinese military classics, among others. It was here that a very select few—some of which came from the same families—would also study shinobi no jutsu, which can be considered as “black ops” and spying. It was through this speciality that the ninja were born.

Shinobi no mono were hired by a lord to act as covert agents and would accompany an army, or infiltrate a target enemy months or years before a campaign was initiated. In Japan’s Warring Period of the fifteenth and sixteenth century, the arts of the ninja were performed by warriors and soldiers of different social standing, meaning that many of the ninja agents were of the samurai class and an unknown percentage were foot soldiers. The position of ninja itself crossed social boundaries. From highly sophisticated and intellectual samurai who had to deal with high end intelligence gathering and operations to low level infiltration commandos, both of whom worked in unison to deceive and disrupt the strength of the enemy. The concept of ninja as a secret underclass or a collection of peasant families against the ruling samurai is a modern myth, and many ninja documents are written by the samurai, and therefore, ninjutsu is a samurai art and is a vital part of the Japanese military machine.

Natori Masazumi himself says that the ways of the ninja are hard to define and that such skills are like a void, there are no edges or boundaries in its description and that no clear line defines that which is a ninja skill and that which is not. Therefore, to understand the subject, consider that ninjutsu is in essence the intention to deceive the enemy or to engage in covert operations. Ninjutsu borrows from other areas; a grappling hook is by no means only used by the ninja, but when used to scale a castle wall by a single operative or small group, it becomes ninjutsu. Likewise, when performing arson, the concept of kajutsu (火術)—fire skills—comes into the realm of ninjutsu. However, the presence of deception does not always equate to ninjutsu; hiding a troop formation or an ambush is not ninjutsu—they are simply military deceptions, and so the lines become blurred on what is, and what is not classed as a shinobi skill. On the whole, a single operative or small group of operatives who actively devote themselves to the deception, infiltration and disruption of the enemy by using techniques which are collectively recorded by the ninja of history can be said to be performing shinobi no jutsu—the skills of the shinobi.

Shinobi no jutsu pertains to skills in the following areas:

• Infiltrating enemy camps, castles, compounds or houses

• Tools used for infiltration

• Spying and intelligence missions

• Battle camp defense responsibilities

• Night patrols

• The discovery of enemy shinobi attempting to infiltrate a camp or castle

• The discovery of enemy shinobi who are in disguise

• Disguise and impersonation

• Counterintelligence systems

• Methods of propaganda

• Close and deep scouting

• Enemy troop observation

• Arson and explosives

• Poisons and powders

• Esoteric magic

• Criminal capture missions

• The discovery of rebellions and plots, both internal and external

All of the above create a network of skills, some borrowed and some specific to the ninja, but all of which represent an auxiliary art used by specific agents known to us as the ninja. For a more detailed understanding of the shinobi see; In Search of the Ninja (The History Press).

Natori-Ryu

Natori-Ryu is the school of gungaku (軍学): military studies of the Natori family. It originated in the second half of the sixteenth century when the Natori clan served the famed warlord Takeda Shingen. The original founder is recorded as Natori Yoichinojo Masatoshi, who was a samurai in the vanguard of Takeda’s army. Initially, the school focused on military strategy and also formed a medical unit, being famous for their secret technique to cure sword wounds. After the defeat of the Takeda clan by the Tokugawa family, the retainers of Takeda Shingen—Natori included—signed oaths to join and fight for the Tokugawa Clan. From here the Natori split up into two main branches, the Edo-Natori line and the Kishu-Natori line.

The Tokugawa Family can be divided into four branches, the main line of the Shogun in Edo (modern day Tokyo) and the three great house of the Tokugawa family (gosanke) which was made up of the House of Owari, The House of Kii (Kishu) and the House of Mito. The former is the seat of the Shogun while the latter three are the lines in place when a male heir is not available from the main line.

Sometime in the first half of the seventeenth century, Natori Sanjuro Masazumi was born into the Kishu-Natori line, the fourth son of Natori Yajiemon Masatoyo. Natori Masazumi—the author of the Shoninki—was to become the chuko no so for Natori-Ryu, meaning “grandmaster of redefinition,” as it was this Natori member who became the core grandmaster of the school. He studied Kusunoki-Ryu from the lineage of Kusunoki Fuden, and along with other schools such as Koshu-Ryu, he greatly expanded the scope of Natori-Ryu and recorded the school’s vast teachings in a collection of scrolls, the Shoninki being one of many. The school curriculum was expansive and reached into all areas of Japanese warfare, from those skills needed to be a samurai of the day to Chinese formations, from the various positions within an army and their given tasks to esoteric cosmology, from weapon and tool terminology and use to the philosophy of the mind and of course, the arts of the shinobi among many, many others.

Sometime in the seventeenth century—according to the Natori Family traditions—Lord Tokugawa Yorinobu instructed Natori Masazumi that he should change the school name from Natori-Ryu to Shin-Kusunoki-Ryu, meaning the new school of Kusunoki. Due to this, various Natori manuals are labeled as both Kusunoki-Ryu and Shin-Kusunoki-Ryu. The general rule of thumb is that anything Natori-Ryu or Shin-Kusunoki-Ryu is the writing of Natori Masazumi, while Kusunoki-Ryu proper have multiple different branches. The original name of Natori-Ryu has been readopted for two reasons; firstly to avoid confusion, and secondly because official Tokugawa Clan records show the school recorded as Natori-Ryu by the nineteenth century.

The school continued in the form Natori Masazumi created until its closure with the Meiji Restoration. The school passed from the Natori family into other hands and back to the Natori family only to be passed on again during its career.

Natori-Ryu Grandmasters

The following is a current list of the Natori-Ryu grandmasters, this list was compiled from records in the Wakayama Prefectural Library in Wakayama city.

1. Natori Yoichinojo Masatoshi (founder)

2. Natori Yajiemon Masatoyo

3. Natori Sanjuro Masazumi (grandmaster of redefinition)

4. Natori Hyozaemon Kuninori

5. Natori (Unobe) Matasaburo (adopted and given twenty koku salary)

6. Ohata Kihachiro (passed it back to the Natori family)

7. Natori Kusujuro

8. Yabutani Yoichi

9. Tomiyama Umon

10. Yabutani Yoichiro

With the close of the samurai age and the Meiji Restoration, the final grandmaster, Yabutani Yoichiro, closed the school due to the modernization of Japan. The old ways of war were being superseded by the modern military. While the main branch closed, at least one line of Natori-Ryu continued to exist on the island of Shikoku, but in the twentieth century that too closed down, making Natori-Ryu an extinct school.

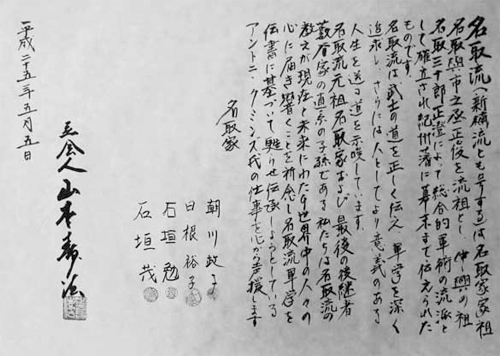

Antony Cummins with Yabutani Itaru, the grandson of the last Natori-Ryu grandmaster

A Biography of Natori Sanjuro Masazumi

The Japanese family crest used by Natori Sanjuro Masazumi

Natori Sanjuro Masazumi was born at some point in the first half of the seventeenth century and was most likely a child of the first or second generation after the great wars. Hence, most older people around him were veterans of the great wars of Japan and that Natori would have been surrounded by battle-tested elders and the sons of those who directly fought in the wars. It is known that his elder brother, Natori Yajiemon Masakatsu, was a retainer to Lord Tokugawa Yorinobu, and that in 1654 Natori Masazumi himself was brought to service as a chukosho—a form squire. Natori appears to have closely served the Tokugawa family for life, holding the following positions:

• chukosho —squire-page

• goshoinban —warrior in service in the castle

• gokinjuzume —close retainer to the lord

• ogoban —military officer

• daikosho —personal attendant to the lord

This means that Natori’s life would have been one of a castle samurai, serving his duties around the Kishu branch of the Tokugawa family, tending to the Lord’s needs and requirements and ensuring his safety as one of his personal guard. When Lord Tokugawa Yorinobu retired Natori Masazumi continued to serve him at his residence until the lord’s death. Outside of those services, he was a dedicated student of war and clearly worried for the future of samurai skills. In his writings he hints that the samurai of his time are starting to forget the old ways of battle and that a new era of peaceful samurai with no experience are rising. For this reason he devoted himself to studying and collecting the secrets of the old ways which are dying around him, and to record them for prosperity. From his teachings he produced a collection of writings that survive to this day:

• A ten volume collection of gungaku military studies manuals

• A single volume containing eighteen short scrolls on warfare

• Three scrolls dedicated to the arts of the shinobi

• A ten volume encyclopedia of samurai equipment and ways

• Nine inherited scrolls of deeper secrets

His collected works are vast and expansive, crossing all realms of samurai life. The Shoninki is only a single work, having its own place within the full catalogue of Natori-Ryu.

In 1685 Natori Masazumi retired to the village of Ono at the foot of Mt. Koya—the holy mountain of the Shingon faith—where it is presumed he taught his grandson, Natori Hyozaemon, the ways of Natori-Ryu after the death of his own son. Natori Masazumi—or Issui sensei as he is known to others—died at an unknown age on the 5th of May, 1708. His death certificate and grave can be seen on pages 103 and 104. His nom de plume was Toissui (藤一水), and his Buddhist death name was Kyugenin Tekigan Ryosuikoji (窮源院滴岩了水居士). His remains were interred at Eunji Temple (恵運寺) in the city of Wakayama. His grave can be seen today, and all visitors are welcome.

Eunji Temple

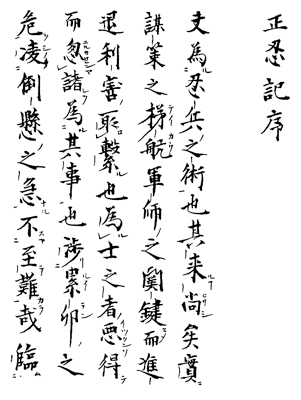

Eunji Temple is the home of one branch of the decedents of the famous warrior Yamamoto Kansuke, and it remains under the care of the Yamamoto Family with the current keeper, Yamamoto Jyuho.

The temple appears to have been a place of worship of decedents for those samurai who served Takeda Shingen and who had moved to Kishu together. The Kishu-Natori branch are interred here, from the beginning of their move to Wakayama up until today. The last male member of the Natori Clan to bear the name Natori was Natori Tetsuo who died in 1949 with no children. His brother, Natori Takao, had already adopted the different surname of Kano and could not return to Natori after the death of his brother. Therefore, the last Natori was Natori Yukiko, but being female, her name changed when she married into the Ishigaki family and she died in 1995. The Natori Clan graves are now under the care of her children—the last true descendants to be born from a named Natori member.

Monk Yamamoto and the temple take a proactive approach to the Shoninki and the skills of Natori-Ryu. The monk has formed a reading study group called “Shoninki wo Yomu Kai” (正忍記を読む会) and hold events and workshops on the study of the text and the promotion of Wakayama. Again, readers are welcome to visit the temple.

Monk Yamamoto Jyuho—gravekeeper to the Natori Family

The Translation

The Shoninki is unlike other ninja manuals. Many shinobi scrolls are simply memorandum lists where the original skill is not described and only a guess can be made regarding its specifics. Others have vast detail, explaining the ways of the shinobi in all aspects, but they are simple in their instruction, and their translation is relatively easy with the only real difficulty being lost vocabulary or poor transcriptions. The Shoninki stands alone from the others because of its style. It assumes that the reader has read and been trained in the ways of all the other Natori scrolls, and therefore a sentence in the Shoninki can be loaded with stacks of required background reading, experience and cultural knowledge. Furthermore, many of the sentences are subjective, other manuals tend to be firmly objective—“do X, move to Y and carry out Z”—but the Shoninki is built on a foundation where such instructional learning has previously been achieved by the student and moves into the realm of a “conversation,” where meaning can be interpreted by the reader. This is clear when read alongside the scroll Dakko Shinobi no Maki as the Shoninki is clearly an extension of that. While the majority of the text is identifiable between different translations, there are aspects where interpretation is required, and no matter who the translator is, personal opinion on meaning has to take place. Our team holds the special position of being the only team to have used the collection of the Natori scrolls to validate our translation of the text and therefore this translation is the only one supported by actual Natori teachings. That being said, at the request of the publisher we took the original translation and spliced the footnotes in for an easier read and also removed all macron markings (ō & ū). Thus, in this version, added information from our background reading is included in the text to ensure a smoother experience for the reader. When reading this version, understand that some of the supplementary information is a combination of information from the other Natori scrolls, academic research and grammatical points to give flow. No matter who translates this text, each person has to step into the realm of interpretation due to its very nature. Of all the manuals left to the world, the Shoninki is the most enigmatic.

It is my pleasure to introduce the second edition of this translation. We have attempted to correct any clear mistakes we made in the first edition and to bring into focus any aspects that were too obscure in our first version. For any differences in text, this edition takes precedence. Since its first publication, our understanding of Natori and his works has grown exponentially, and we can now minimize those areas of subjective interpretation, bringing us closer to Natori Masazumi’s original vision.

Natori-Ryu Reborn

The final days of Natori-Ryu were played out in the twentieth century as the last known branch closed its doors, and the manuals were placed on shelves to wait for a new surge of life. The wonderful aspect of Natori-Ryu is that the scrolls are filled with detail, the prime example being the Shoninki. The other Natori-Ryu scrolls possess equally detailed information, each one working together to form a collective set of teachings. In the instances where the text is vague, fortune has provided multiple transcriptions, each one with additional commentaries. These commentaries are the oral traditions which accompany the scrolls but which were written down at a later stage, providing the hidden details and leaving only a very few unanswered questions. Such favorable circumstances has left a window for the school to be resurrected and re-established as one of the premier war schools of samurai arts.

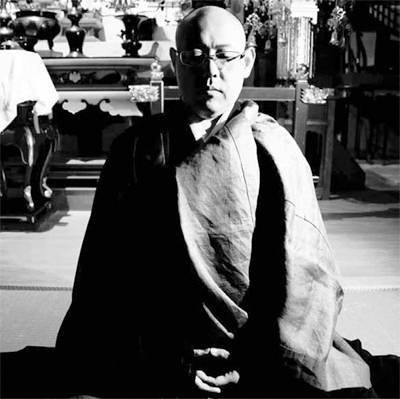

The blessing given by the Natori Family on the 5th of May, 2013

On May 5th, 2013, the remaining Natori Family members in the presence of Monk Yamamoto at Eunji Temple gave their blessings for Natori-Ryu to be resurrected under my guidance. With the support of both the Natori Family and the temple, the school has enjoyed a successful rebirth and is currently active.

Alongside this volume of the Shoninki, Natori-Ryu’s teachings are also given in full in The Book of Samurai series

The resurrected Natori-Ryu is comprised of groups who dedicate themselves to the teachings of Natori Masazumi and who communicate with other members around the world. The school is active on most social media platforms and we encourage people to get involved with the school’s ancient teachings. All members come together in the spirit of research and development with the aim to help one another understand the benefits of old Japanese ways. Currently the focal point for all students of Natori is the Facebook group “Natori Ryu Hub,” and I invite you to explore and discover our school. Further information can be found at our website: www.natori.co.uk. All that remains is to encourage you to study this manual instead of simply reading it, and enjoy these teachings while you find a place for the principles within your lives.

— AntonyCummins