The Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan

Campaigns Against an Elusive Enemy

A U.S. Army soldier mans a .50 caliber machine gun above the town of Kamdesh in eastern Afghanistan in 2012. This remote area was an important strategic position for intercepting enemy fighters and weapons coming from neighboring Pakistan.

A Taliban fighter on patrol in November 2001, just weeks after U.S. special forces entered Afghanistan in an effort to remove the Taliban from power.

The United States went to war soon after the attacks of September 11, 2001 (see Surprise Attack). This was the most devastating surprise assault on the American homeland since Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese in 1941. But the enemy in this case was not another nation. Instead, it was an international group of terrorists known as al-Qaeda. Soon after the attacks, President George W. Bush said, “Our war on terror will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated.” The targets in this war included terror organizations as well as the nations that supported them and gave them refuge.

In October 2001, the United States sent special forces into Afghanistan. Osama bin Laden, head of al-Qaeda and mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, was living there under the protection of the Taliban, an extremist Islamic group that ruled Afghanistan. The Taliban refused to hand over bin Laden to the United States. In less than a month, American soldiers, supported by the armies of local warlords in the Northern Alliance, drove the Taliban from power. Many members of bin Laden’s group were killed in the first days of the U.S. assault, but bin Laden escaped. He became the subject of the most determined manhunt in American history, and he was finally discovered almost ten years later to be hiding in Pakistan. American SEAL Team 6 launched a raid on bin Laden’s walled compound and killed him on May 2, 2011.

The Search for Dangerous Weapons

The next front in this war on terror was Iraq, a country controlled by the dictator Saddam Hussein. Since 1990, the United States believed that the Hussein regime supported terrorism. Hussein had used chemical weapons against his own people more than once, and the United Nations had punished his regime by preventing other nations from trading with Iraq. In October 2002, a large majority in the U.S. Congress authorized the use of force against Iraq. This decision was based on intelligence information—later proved to be wrong—that the Hussein regime had a large supply of weapons of mass destruction, possibly including nuclear devices. The fear was that the regime could give these weapons to terror groups for use against the United States and its allies. The war began in March 2003, and Iraq’s capital city, Baghdad, fell to U.S. forces a month later.

Americans began to question the Iraq invasion when no weapons of mass destruction were discovered. Also, what appeared to be an easy victory soon became a prolonged struggle against an uprising by Iraqi extremist groups, as well as violent clashes among different factions. Over the next few years more than four thousand Americans were killed in the fighting.

In 2007, a surge of additional troops were sent to Iraq, which stabilized the situation. American combat soldiers were withdrawn from Iraq in 2011, although they continued to fight in Afghanistan, where, since the original 2001 invasion, the Taliban had regrouped and began waging a guerrilla campaign against the government throughout the country. The war in Afghanistan is already America’s longest in its history.

The Islamic State

Events in Iraq and Afghanistan have shown that it is far easier to start a war than end it. After the United States withdrew from Iraq, the terror group previously known as al-Qaeda in Iraq began to gain power there. Other fighters joined them, particularly Islamic extremists who were also fighting in the civil war in neighboring Syria, which began in 2011. Al-Qaeda in Iraq renamed itself the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS)—which it later shortened to the Islamic State (IS)—and began a terror campaign in Syria and especially in Iraq. Iraqi forces, no longer backed by American troops, were powerless to stop it.

The Islamic State doesn’t want only to wage a terror war; it wants to control territory and to set up a worldwide Islamic extremist government. By the middle of 2014, as its strength grew to an estimated 30,000 fighters, IS had conquered large portions of Iraq, including Mosul, the country’s second largest city. In the area it controlled, the Islamic State became notorious for genocidal attacks on Christians and members of other religions who refused to convert to radical Islam, and on the Kurds and other ethnic groups. IS was condemned as a terrorist organization by the United Nations, the European Union, the United States, and Japan after it beheaded Western prisoners and showed these executions on the Internet. As a result of these televised murders and the Islamic State’s territorial gains, in 2014 the United States, with a coalition of allied aircraft, began an air campaign against IS in Iraq and Syria. In addition, American specialists began training select rebel groups to fight IS in Syria and advising and training Iraqi forces to fight IS in Iraq.

The U.S. Navy launched its first drone from an aircraft carrier on May 14, 2013. These unmanned, armed aircraft are deployed for surveillance throughout the world wherever terrorist groups might be hiding.

Medal of Honor Recipient, Afghanistan

SALVATORE GIUNTA

Bringing a Buddy Home

Salvatore Giunta

· Born 1985, Clinton, Iowa

· Enlisted in U.S. Army, 2003

· Service in Korengal Valley, Afghanistan, 2007

· Rank: Specialist

· Unit: Company B, 2nd Battalion (Airborne) 503rd Infantry Regiment; 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team

· Received Medal of Honor, 2010

“This is my chance. I can make a difference.”

Salvatore Giunta was eighteen, a kid from middle America, just out of high school and working part time as a “sandwich artist” at Subway in late 2003. He had no idea what he was going to do with his life when he heard a radio commercial for the U.S. Army that would change everything.

It had been two years since the United States was attacked by Islamic terrorists on September 11, 2001. Sal’s chemistry teacher had rushed a television into the classroom the morning that hijackers crashed two jets into the World Trade Center in New York City just as the second plane hit the second tower. “It was our first view of evil,” Sal said.

Over the next couple of years, Sal couldn’t shake the image of New Yorkers running for their lives as the towers collapsed. It stayed with him as he graduated from high school with an undistinguished record, took the job at Subway, and tried to sort out what he’d do with his life. He made an appointment with an army recruiter, telling himself he was only interested in the free T-shirt offered on the radio. But by the time he arrived at the recruitment office, he had made up his mind. He volunteered on the spot. “Here’s my chance. I can make a difference,” he said to himself. “I’m going to do this.”

Sal’s story started in another country, as so many American stories do. His great-grandfather and great-grandmother on his father’s side were from Sicily; like millions of other immigrants, they came to America at the turn of the twentieth century looking for a better life. Over the next two generations, the Giuntas worked so hard at becoming American that when Sal was born in 1985, the family’s Italian roots were just a pleasant memory.

Growing up in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, in “a Midwest, middle-class, sunshine, rainbows, green grass, you-do-not-have-to-lock-your-door sort of neighborhood,” as Sal calls it, was everything a kid could want. Sal was popular and had many friends, but he admits that he was a mediocre student, not really interested in school and doing just well enough to get by: “I’d just sit there in class, half interested, half daydreaming—a kid who would rather have been somewhere else.”

Sal Giunta stands beside a military jeep. Various guns are frequently mounted on jeeps and other vehicles to provide a quick means of defense from enemy fire.

Then came 9/11, which eventually led Sal to give up his comfortable midwestern life to serve his country. It was a decision he never regretted. “I learned twenty valuable lessons before seven o’clock every morning when I first got in the Army,” he says. A good football player in high school despite his average size, he added muscle during basic training and felt that he was ready for any challenge.

At Fort Benning, Georgia, Sal learned how to parachute out of planes as a member of the 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team—the Sky Soldiers—which had first distinguished itself in the Vietnam War. His first posting was at the American base in Vicenza, Italy, which gave him a chance to explore his Italian heritage during weekend leaves. While there, he also got to talk to some of the first U.S. soldiers who had fought in Iraq. The stories they told sharpened his appetite for combat. He was excited when his unit was deployed to Afghanistan in the spring of 2005; at last he’d have the chance to take revenge on the terrorists responsible for the attack on America.

The Truth About War

But Sal soon learned firsthand that while war might be about patriotic ideals, it was also about death and loss. In his first three months in Afghanistan, he saw four of his buddies killed by a roadside bomb that destroyed the truck they were riding in. “These were people in the prime of their life,” he says. “They were not people who ate too much greasy food and had a heart attack. They would never be stronger than they were on that day when suddenly they had no more tomorrows. These deaths affected me. I lost some of the excitement, but I wanted to get the job done more than ever.”

Sal’s first tour in Afghanistan lasted for a year. In the spring of 2007, his unit returned for a second tour. This time it was helicoptered into a place called Firebase Vegas in the remote Korengal Valley, near the border with Pakistan. “It was like nothing I had ever seen in Afghanistan before,” Sal recalls. “We were at the bottom of the valley, with mountains just straight up and down on every side. Every place you’re going to fight, you’re at the bottom and they are at the top. You’re in the open and they have cover.” The place was known as the Valley of Death, because so many American servicemen had died fighting there.

Over the next few months, the soldiers at Firebase Vegas helped build roads and completed other projects to improve the lives of the locals by day and hunted the “bad guys” in night raids. On October 23, 2007, his company was at the end of a five-day-long mission to clear out groups of Taliban fighters before winter arrived when the enemy overran one of the company’s reconnaissance patrols, killing a staff sergeant and wounding two other Americans. Sal and the others had heard it happen on their radios. “We were only a kilometer away,” he remembers. “We were listening to a million bad things happening to our brothers.”

Two days later, when word came that the Taliban were showing off the weapons and equipment they had taken during this firefight as “war trophies” in a local village, Sal’s company commander ordered two platoons to get them back. Sal’s platoon took a position on a mountain ridge overlooking the town to provide cover for this mission.

Ambush!

Shortly after nightfall, the U.S. equipment in the village had been recovered without incident, and Sal’s eight-man platoon was ordered to return to base. Their way lit by the full moon, they had walked for about five minutes and entered an open area when rocket-propelled grenades and machine-gun fire suddenly began to explode all around them. There were a few shrubs and bushes, but nothing that would stop a bullet. The platoon had walked into an L-shaped ambush, in which the enemy was along one side and ahead of them.

The gunfire was more intense than anything Sal had ever experienced. “There were more bullets in the air than stars in the sky,” he later said. “They’re above you, in front of you, behind you, below you. They’re hitting in the dirt; they’re going over your head. They were close—close as I’ve ever seen.” Apache helicopter gunships were circling above the action, but the Americans and Taliban were so close together that the aircraft couldn’t open fire for fear of hitting their own men.

Sergeant Joshua Brennan was leading the platoon when the firing erupted. He was hit several times and fell to the ground. Specialist Hugo Mendoza, the squad medic, rushed forward to help Brennan, but was himself shot and killed. Sal saw squad leader Erick Gallardo’s helmet jerk as he, too, went down. Fearing that Gallardo had been shot in the head, Sal ran through heavy fire to get to him. But the bullet had only bounced off Gallardo’s helmet. Sal pulled him back to a small depression in the ground, maybe six inches deep, where the two of them lay as flat as possible. An enemy round hit Sal in the chest, but his protective vest stopped it. Another bullet, that otherwise would have hit him in the neck, struck the rocket launcher he was carrying over his left shoulder and shattered it.

Realizing that the Taliban fighters were on the verge of overrunning the unit, Sal stood up and counterattacked. “I am throwing my grenades,” he recalls. “I only had three with me, and then there were no more grenades and I was running forward toward the shooting.”

Sal frantically looked for Sergeant Brennan as he charged ahead, not knowing how badly he was hurt but hoping to drag him back to safety. He and Josh Brennan were close friends. They had traveled through Italy on weekends when their unit was stationed at Vicenza and had served side by side on both tours in Afghanistan.

Sergeant Joshua Brennan was wounded when Taliban fighters ambushed his platoon in 2007. Sal rescued his friend from enemy hands and returned him to American lines.

Finding a Friend

But Joshua was not where he had fallen when hit by a volley of enemy bullets. Searching for his friend, Sal sprinted through some low shrubs and into a clearing he later described as a “scary, empty, flat space.” In the distance, he made out the forms of what he thought at first were three men running away. But then he realized that it was actually two Taliban fighters who were dragging a third man—Sergeant Brennan. “This part haunts my dreams,” Sal says. “Joshua is like a brother to me. He’s smarter than me and stronger than me, faster than me, and a better shot. But here, he’s the one getting carried away.”

Firing as he ran forward to get his friend, Sal killed one of the Taliban and wounded the other, who dropped Sergeant Brennan and limped off. Sal reached his buddy, picked him up, and carried him back to the open space where the other members of his squad had set up a defensive position. He quickly examined Joshua: “I think he was shot maybe seven times, and maybe a rocket-propelled grenade hit the ground nearby and shrapnel had taken off part of his jaw.” Sal called for Mendoza, the squad’s medic, not knowing that he’d already been killed. He tried to reassure Joshua that he’d make it, as he and the other GIs gave him medical aid. “You’ll get out and you’ll tell hero stories,” he yelled to his friend above the battlefield din. Joshua nodded weakly.

By the time the medevac helicopter arrived for Sergeant Brennan, the Taliban had melted away into the night. Sal and his unit walked two and a half hours back to the base. It was one o’clock in the morning and they were eating their first hot food in days when the company commander came into the mess hall. He told them that everyone else was going to be okay, but that Joshua Brennan had died. “That was my hell,” Sal remembers. “That was my bad day.”

In Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley, Sal Giunta’s platoon is in full desert camouflage. The men are carrying their personal weapons for rapid response against surprise attacks.

Singled Out for an Honor

A week or so later, Sal learned that he had been recommended for the Medal of Honor. At that time, six other U.S. servicemen had received the award for heroism in Iraq and Afghanistan, but all of them had been killed in action. Sal would be the first living recipient of the medal in forty years, since the last days of the war in Vietnam.

In the three years it took for the recommendation to be investigated and approved, Sal sometimes felt a kind of dread—not only because he knew that receiving the medal would change his life, but also because he believed that all the others involved in that fight in the Korengal Valley were as worthy of the honor as he was. He felt uncomfortable being singled out. “I got congratulated and patted on the back and kissed and loved,” he says. “But it hurt because I know that there are guys who will never get congratulations or thank-yous or see their family or their children.” The only consolation was that the last thing his friend Joshua Brennan had seen was Sal and his other buddies taking care of him. Brennan had not died in enemy hands.

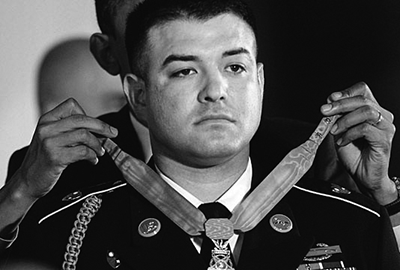

President Barack Obama fastened the medal around Sal’s neck at the White House on October 25, 2010. “I can say at the end of my life that I fought for this country the best I knew how, and the Medal of Honor represents that,” Sal said at the time. “It represents everyone who left their life behind wherever they were—in Iowa or New York or California or Florida—to do something not for themselves but for their country. It’s about people who did that yesterday, are doing it today, and will be doing it again tomorrow. No matter how bad things are, no matter how big their losses are, they will continue to do it because that’s what makes America great.”

In 2010 President Barack Obama awarded the Medal of Honor to Sal Giunta, who was the first living person since the Vietnam War to receive the U.S. military’s highest decoration for valor.

Who Are the Taliban?

The Taliban are a group of terrorists in Afghanistan who practice an extreme form of the Islamic religion that condones the killing of “infidels” (nonbelievers and Westerners). Every aspect of life under the Taliban is regulated. Men are forced to grow beards, and everything about women’s lives—from how they look to where they are allowed to go—is controlled by male authorities. Television, movies—even video games—are forbidden. Those who fail to obey are subject to severe punishments, from chopping off the hands of those accused of stealing to beheading those who question Islam.

The Taliban began as a group of a few dozen fanatical students in Afghanistan who fought the Soviet Union when it occupied their country from 1979 to 1989. After the Soviet Union withdrew, the Taliban continued to fight against other Afghan groups for control of the country, which it took in 1996.

Strict Rules for Daily Life

While in power, the Taliban enforced a rigid form of Sharia—Islamic law that governs every detail of daily social life. Under its brutal rule, harmless activities, such as listening to music, playing chess, and flying kites, were banned. Public executions of lawbreakers were held in sports arenas. Women were forced to wear full-length burkas—black garments covering them from head to toe, with only a slit for their eyes. If they left the house without a male escort, they were beaten by the religious police who patrolled the country’s streets. A woman caught wearing nail polish might have the tips of her fingers cut off.

Believing that Islam was in a war against the West and its democratic values, the Taliban allowed Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaeda, a terror group that had launched attacks against the United States around the world in the 1990s, to set up a headquarters in Afghanistan, where it planned the 9/11 attacks.

A month after those attacks, U.S. Special Forces moved into Afghanistan. Fighting alongside tribal groups who opposed the Taliban, they forced them out of power that same year. Most of the Taliban leaders hid in neighboring Pakistan and waited for an opportunity to resume their fight.

That opportunity came after the United States invaded Iraq in 2003. While America focused its attention there, the Taliban took up arms once again. In 2004, Afghanistan held its first democratic election (with women casting 40 percent of the ballots) even though the Taliban threatened to kill anyone who voted. The United States backed the newly elected central government, and the Taliban re-formed into a guerrilla force.

The Taliban has fought against the elected government of Afghanistan and U.S. forces for more than a decade. By 2014, an estimated thirty thousand Taliban had been killed, while twenty-three hundred Americans, along with nearly fifteen thousand Afghan government troops, had also died in this war, the longest in U.S. history.

A group of Taliban fighters. Many weapons used by the Taliban, such as the rocket-propelled grenade and the A-K 47, were developed in the Soviet Union and used against the Afghan population during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s.

Medal of Honor Recipient, Afghanistan

CLINTON ROMESHA

Born to Fight

CLINTON Romesha

· Born 1981, Lake City, California

· Enlisted in U.S. Army, 1999

· Rank: Staff Sergeant

· Unit: Bravo Troop, 3-61st Cavalry, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry

· Service at Outpost Keating, Nuristan Province, Afghanistan, 2009

· Separated from Army, 2011

· Received Medal of Honor, 2013

“Your actions are what make you.”

When Staff Sergeant Clint Romesha (pronounced Rome-uh-shay) arrived at Outpost Keating in Afghanistan in the summer of 2009, he felt that for the first time in nearly ten years in the Army, doing mostly noncombat jobs, he was in a place where anything could happen.

Clint and his men were now in the most dangerous spot in the most dangerous country for an American soldier, and they were badly outnumbered by the Taliban. The fight for Outpost Keating would be one of the most fearsome of the Afghan war, and Clint would be at the center of it. He seemed destined to be there.

Named for Benjamin Keating, an American officer who had been killed there in 2006, the outpost was near the town of Kamdesh in a remote and desolate province in eastern Afghanistan on the Pakistan border.

Clint was struck by how vulnerable the American position was—a few prefabricated buildings sitting in a bowl at the base of three steep mountains so dense with trees that they were perfect cover for snipers and staging areas for enemy attacks. The roads from the closest big city, Jalalabad, were narrow, poorly constructed, and filled with the carcasses of American trucks and Humvees ambushed there over the years. Taliban fighters hiding in the ridges above let loose rocket-propelled grenades and heavy machine-gun fire when the helicopters carrying most of the camp’s supplies appeared. The pilots had begun limiting their flights to moonless nights when the darkness offered at least a little protection.

The outpost was designed as a place where U.S. forces could intercept enemy fighters and weapons coming in from Pakistan. Another part of the mission there was “counterinsurgency”—an effort to improve the lives of local tribesmen and convince them that it was in their interests to oppose the Taliban. As part of this counterinsurgency effort in Kamdesh, the Army had spent millions building schools, electricity grids, water systems, and other improvements.

But winning the hearts and minds of the locals had been an uphill struggle. Most people around Kamdesh were illiterate, opposed to their country’s central government, and suspicious of all outsiders. And because the Taliban had murdered many of the tribal leaders who cooperated with U.S. reconstruction projects, local residents became afraid to continue to participate in the program. Soon after Clint arrived at Outpost Keating, an official army study concluded that because counterinsurgency efforts had failed, there were more enemy fighters in the area and the outpost was “indefensible.” A decision was made to close it.

Clint Romesha (center) with his men at Outpost Keating in eastern Afghanistan.

All in the Family

Clint understood the dangers he faced at Outpost Keating. But he also felt that he had been born to fight in such a difficult situation. His grandfather had been an army combat engineer in World War II and had distinguished himself in the Battle of the Bulge. His father had done two tours of duty in Vietnam. His two older brothers joined the military. As a kid in the tiny northern California town of Lake City (population 60)—a place so small, Clint liked to joke, that “it was hard to find a girl to date who wasn’t related to you”—he had thought of the military as a family business where he would someday have a job, too.

As a teenager, Clint longed to be a basketball player, but because he was short and wiry he became a soccer player instead. His friends saw him as someone with an edgy sense of humor who thought that actions were more important than words. “My granddaddy taught me that you tell someone you’re going to do something, you do it,” he liked to say. “Your actions are what make you.”

Clint joined the Army shortly after his eighteenth birthday in 1999. He trained as a gunner for the M1 Abrams tank and was sent to Germany. Two weeks later, his armored battalion was reassigned to Kosovo in the Balkans as part of a NATO peacekeeping force. (Their mission was to keep the war that Serbia had fought against the Albanian population of this area from resuming.) His unit was given the mission of protecting the mass graves of civilians killed by the Serbians. “The only shooting we did,” Clint recalled, “was of wild dogs that dug up these burial sites.”

Clint returned to Germany in 2000. It was there that he saw the attack on the World Trade Center on TV, and later watched U.S. Special Forces enter Afghanistan to root out the Taliban terrorists who had supported the attack. He wanted to get in the fight, but the mountains of Afghanistan were no place for tanks.

Instead, Clint was sent to South Korea for fifteen months, and then to Iraq in 2004. He came home to Fort Carson, Colorado, in 2008 and was retrained as a cavalry scout operating in hunter-killer teams to collect information on the enemy and engage it in small mobile units. As he put it, he learned “to get light and how to sneak around.”

Test of Bravery

When his commanders told Clint’s unit that it was being sent to Outpost Keating, they frankly admitted that it was a dangerous assignment. In the three years the outpost existed, many American soldiers had been killed. “We knew it was going to be hairy,” Clint later said. “But true-grit soldiers do what they have to do.”

Outpost Keating was manned by about fifty U.S. soldiers and another thirty-five or so Afghan government troops. Clint said, “We were getting hit at least once a day. Those were probably efforts to test our ability to react. When I was in Iraq, I hadn’t been impressed by the enemy. But these Taliban fighters were well trained. They knew how long they had to attack us before our air support arrived.”

Local Afghans had been telling the Americans for days that many more Taliban than usual had entered the area. But with no electronic intelligence to back up the warnings, the camp commanders ignored them. Then, at 6:00 a.m. on October 3, 2009, about three hundred enemy fighters launched a carefully coordinated attack that began with rocket-propelled grenades and heavy machine-gun fire.

“At the beginning it was the zip and ping of bullets and sudden destruction,” Clint recalls. He understood immediately that the enemy was probing for weak spots where it could break through the American defenses and enter the outpost. The Taliban began by destroying the American mortar position, which had the only weapons capable of firing effectively into the staging areas in the mountains. Small groups of heavily armed enemy fighters then rushed Outpost Keating’s defensive perimeter.

“In heavy contact!” the outpost’s command center radioed the U.S. base in Jalalabad, which radioed back that helicopter gunships had taken off but were at least forty minutes away.

Clint saw most of the Afghan government soldiers throw down their weapons and slink away as the fighting began, some hiding and others joining the Taliban. He heard over his radio that Americans were pinned down throughout the main compound, some wounded and some dead. As a staff sergeant, he was one of the most visible leaders at the outpost. Now, moving through the enemy fire, he tried to deploy his men at key positions to keep the post from being overrun.

Two Apache helicopter gunships finally arrived and began spraying the enemy with their machine guns. The Taliban opened fire on them with the heavy weapons they had hidden in the mountains. One of the Apaches was hit and forced to return to base. The pilot of the other one, seeing the Taliban advance as the outnumbered U.S. troops pulled back, radioed Jalalabad that the situation was “potentially catastrophic.”

About two hours after the battle began, the Taliban finally breached Outpost Keating’s defenses and set many of the buildings, constructed of flammable plywood, on fire. They were now coming through the compound’s front gate. Realizing that the situation was critical, Clint and his assistant gunner ran to the barracks, grabbed an MK 48 machine gun, and then headed for the camp’s generator to use it for cover. Clint destroyed a machine-gun position that had been cutting down U.S. troops. But a rocket-propelled grenade slammed into the generator, and shrapnel shredded his upper body.

Clint checked to make sure his gunner was okay and moved to another position. A soldier fighting beside him quickly put a bandage over the large hole in Clint’s arm to stop the bleeding. Disregarding his wounds, Clint thought to himself, “We need to retake this compound now!” Having left the machine gun back at the generator, he picked up a rifle he saw lying on the ground and opened fire on an enemy position on the hill above the compound. He destroyed it, then killed three enemy fighters running toward him.

Clint remembers feeling oddly focused in the confusion of the gunfight: “When things get chaotic, I’ve always been able to break them down into their basic elements instead of getting overwhelmed. The strange thing was that as this battle progressed, I felt I was finally doing my job. I was getting my ultimate manhood test. It was time for us to shine and show what we could do.”

A group of Taliban approached the ammunition depot, whose doors had been destroyed. Clint knew that if they took control of the building, it could mean that the badly outnumbered American force would be wiped out.

Clint ran inside one of the barracks being used as a defensive position and asked for volunteers to save the depot. Five men stood up, and one of them called out, “We’ll follow you anywhere.” With Clint leading the way, the small squad ran through heavy fire to the corner of the ammunition depot, mowing down several Taliban fighters coming at them.

Clint on leave with his infant son.

Pushing Back

As Clint directed his team’s fire and dodged sniper bullets all around him, the Americans slowly pushed the enemy away from the building. When he got to the depot doorway, he radioed the outpost’s command center to tell an approaching U.S. fighter-bomber to drop its load as close as possible, because the enemy was only a few yards away from his men. Clint’s actions allowed the Americans fighting from various positions in the compound to regroup and retake the initiative. As they began to move forward, he provided cover for three wounded Americans trying to get to the aid station. Then he rushed into heavy fire to recover the bodies of two of his fallen comrades, so that the Taliban couldn’t carry them away as trophies of war.

“I knew we had some momentum and had to keep pushing,” Clint explained. “We advanced on the enemy, using heavy fire to back them out of the front gate. We tossed smoke grenades and used the cover they provided to close the gate.”

By 6:00 p.m., after twelve hours of fighting, the Battle of Kamdesh, as it would become known, was over. Eight American soldiers were dead, making it one of the bloodiest battles of the war. The U.S. forces had killed an estimated 150 Taliban fighters.

Three days later, the entire U.S. force evacuated Outpost Keating by helicopter. “We had rigged all the buildings with explosives set to go off thirty minutes after we left,” Clint recalls. “But they didn’t go off. An Air Force B-1 bomber finished the job.” Afterward, aerial photographs showed only faint indentations in the ground where buildings had once stood.

U.S. soldiers fire a 120mm mortar at a Taliban position from a combat outpost in Kunar, in eastern Afghanistan. Mortar fire, often with helicopter backup, was one of several offensive tactics used against the enemy.

At the White House

A year and a half after the battle, Clint left the Army to spend more time with his wife and children. He settled in North Dakota and took a job in the oil industry. In October 2011, he received a call from Washington informing him that he was to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

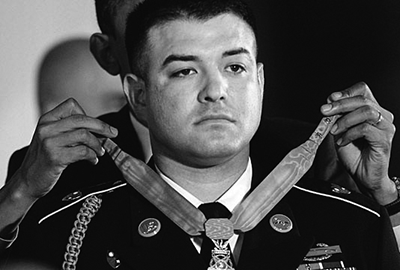

When Clint arrived at the White House for the medal ceremony on February 11, 2013, First Lady Michelle Obama asked him to be her guest at the State of the Union address scheduled for the following evening. He accepted the invitation, but after President Obama put the medal around his neck in front of a group that included not only his family but also many of the men he had served with at Outpost Keating and the wives and children of some who had died there, he whispered to the president that on second thought he’d rather spend the evening with the people who had stood with him on that day in Kamdesh.

For his actions in the twelve-hour battle of Kamdesh despite being badly wounded, Staff Sergeant Romesha received the Medal of Honor in 2013 from President Barack Obama.

Some of the details about the Battle of Kamdesh are from The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor, by Jake Tapper (Little, Brown and Co., 2012).

It happened on a routine mission in Iraq: A roadside bomb exploded and forever changed the lives of a soldier and her family. Mother and daughter both give their accounts, each from her own point of view.

War Wounds That Last a Lifetime

by Juanita Milligan

In the summer of 2005, I was an army platoon sergeant in the 465th Transportation Company in Balad, Iraq. Our job was hauling ammunition, food, and supplies to our troops all over Iraq. Our convoys consisted of twenty tractor-trailer trucks with civilian drivers protected by four heavily up-armored Humvees with three soldiers in each, including a gunner operating a large-caliber machine gun mounted on the roof. I was always concerned when we were on a mission, but there was some comfort in the layer of metal between us and the unseen bombs we knew were hidden along the roads we traveled.

On the morning of August 20, I had a momentary thought that something might go wrong. I quickly dismissed it, but sure enough, midway through our mission, one of these roadside bombs ripped through the passenger side of our vehicle where I was sitting. Everything turned to slow motion. I remember seeing the debris raining down on our windshield. Training kicked in, and I started looking out for my teammates and assessing our situation. Not realizing how bad my injuries were, I reached up for our gunner who was partially exposed to the fury of the blast, wanting to help him, unsure if he was alive. Thankfully he was okay, but I wasn’t. Shrapnel had severed two nerves in my upper arm, taking soft tissue with it. The explosion had blown more shrapnel through my seat, crushing my femur and taking a chunk out of my leg. Shock wore off and pain rushed in.

Master Sergeant Juanita Milligan.

In a past war, my life would have ended on the hot asphalt in Iraq. But improved medical technology—and the bravery of my three comrades, who drove me in another Humvee to the forward operating base—gave me a second chance. Thinking of my children kept me alive as we raced down that highway toward an aid station. The bumpy ride of recovery I took them on over the next few years would be filled with heartache and worry about the way their lives had been altered. They learned, as I did, that not all the wounds of war are visible from the outside. The majority of service members who come home with serious injuries are forever changed. I am no exception. What would be asked from those I love most was unimaginable.

Once I was loaded in the medevac helicopter, my mind went blank; to this day I have not fully recovered my memory of the two weeks post-blast. When I finally came to, I was on more narcotic pain-killers than my body could handle. I had extreme hallucinations, so intense that at times I could not be left alone. The constant hum and buzz of the lifesaving equipment I was hooked to seemed very loud and abstract. I couldn’t keep my mind from replaying the events of the explosion over and over. It was as if a twenty-four-hour news station were playing, so constant that at times I thought I was losing my mind.

Juanita was in a Humvee providing security for a convoy of supply trucks bringing ammunition and supplies to American troops in Iraq when a roadside bomb ripped through the side of the vehicle.

The doctors kept saying I looked great. I knew I didn’t. I was desperate for the truth—especially from someone who would not tell me how great I looked. Frustrated, I dragged myself to a deserted hallway to telephone a dear friend and found myself crying so hard I couldn’t speak.

Out of my four-wall cocoon, I finally realized many service members were worse off than I, but that did not stop the stages of grieving. I saw hundreds of soldiers during my recovery who were in the same boat: passing through the rotating door of pain and healing, searching for our new normal, constantly longing for our former selves while struggling with the uncertainty of the war, which the comrades we left behind are still fighting.

Many of the wounded warriors I have had the privilege to know at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and over the years had such courage and fighting spirit that they gave me strength. Seeing what some of them had to overcome made fighting my own battles seem like a cakewalk. Our battle motto is “leave no man behind,” but sometimes here at home our wounded feel they have to fight their personal war for recovery alone.

At last count, I have been rolled into the operating room twenty-seven different times and have had 102 medical procedures over a seven-year period. Like others who have been seriously wounded, I sometimes yearn for the person I once was. But I only have to look to the service member on my left or right to feel part of a very brave band of brothers and sisters.

So I was very honored to represent all of our country’s wounded warriors when the Congressional Medal of Honor Society presented me with the Courageous Spirit Award in 2008. It can take years to recover, but the real heroes are those who made the ultimate sacrifice for our nation and the families they left behind.

The Congressional Medal of Honor Society presented Juanita Milligan with their Courageous Spirit Award in 2008.

A Daughter’s Story

A Daughter’s Story

by MattieMae Milligan

Let me start by saying that I love my mother very much. What I am about to reveal is truthful, although sometimes it is not pretty.

Being a teenager is hard enough, but my experience was also marked by the news that my mother’s convoy had been hit by a roadside bomb in Iraq. When the family friend serving as one of our guardians woke me early one Saturday morning, I naturally assumed I was in trouble. As I walked up the stairs to our living room with my older brother, Scott, seventeen, an unspoken knowledge was in the air: Something was up. We met my younger brother, Sammy, twelve, in the hallway. As we made our way to the couch, both my guardians sat in front of us, their faces pale. When they began to tell us what had happened, my mind went numb.

Scott was moving into his life as an adult. Sammy had been diagnosed with autism when we were only toddlers. So when I heard the news about my mother, I knew that most of the responsibility of caring for our mother would fall on me. We had an enormous amount of help at the beginning. Getting things ready for my mother to come home required financial support as well as manual labor. I will be eternally grateful to every person who helped our family. But slowly that support faded, and even though I was just fourteen I became the “head” of our household. My new roles were nurse, cook, maid, counselor. Going to school every day caused me anxiety because I didn’t know if my mother was safe at home, not from others but from herself. I wasn’t old enough for a driver’s license and made illegal trips in the car to various places, like the grocery store, at least twice a week. The weight of the responsibility I was given would make me feel resentful toward my mother. My definition of a normal life had been altered forever.

Juanita’s daughter, MattieMae, was just a teenager when she became her mother’s chief caretaker and best friend. This photo was taken before Juanita was deployed to Iraq and subsequently injured.

The Long Wait for News

During the time between when we found out about the injury and when my mother returned to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Washington, DC, the only people able to communicate with the Army were my grandparents. The information we received about my mother was vague. We were unsure of how severe her injuries really were or when we would even be able to see her.

I traveled to visit my mother at Walter Reed several times after she came home. I will never forget the first time I saw her. She was lying there with a tangle of tubes connected to her. Bandages covered all of one side of her body. As we spoke to her, we realized it was going to be a long road back to her normal self. Now I know we were entirely too hopeful. Once, when she asked for some apple juice, I went out to the fridge to get her some. When I came back into her room, she looked at me and got so excited. She had forgotten that I had been there just minutes before. We had to start our conversation over again. She couldn’t understand why I began to cry a little when we were talking. Finally, I told her that I had been there for hours, and then she began to cry, too.

A Healthy Outlet

Coping was extremely difficult. As my mother healed, knowing which role I was playing, caretaker or daughter, involved a constant struggle between us. Each day I did what I had to do to get to the next day. I searched for activities that I could pursue given my new responsibilities. The only one that seemed to work was the sport of softball. I buried myself in it. Any spare time I could find, I would practice. I used this outlet to get away from my mother and my responsibilities. Eventually I would play in college.

If I have learned anything, it is that people do not change; life changes them. My mother will never be the woman who left home in 2004 to fight a war in a foreign country. For the longest time, I wrestled with this concept. Years passed before I could truly say that I understood and accepted that fact. Every once in a while, a glimmer of the woman I used to know comes back to life. I am grateful for every one of those instances, and I hope for them every day.

Many people call my mother a hero. But my heroes will forever be the men that saved her life on that fateful day, the men who risked their lives to save just one person. They will always have a special place in my heart.

Juanita endured multiple surgeries and years of physical therapy to treat the severed nerves in her arm, side, and leg.

Medal of Honor Recipient, Afghanistan

LEROY PETRY

A Ranger Leads the Way

Leroy Petry

· Born, 1979, Santa Fe, New Mexico

· Enlisted in U.S. Army, 1999

· Rank: Sergeant First Class

· Unit: Company D, 2nd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment

· Service in Afghanistan, 2008

· Redeployed to Afghanistan, 2011

· Received Medal of Honor, 2011

“Those were my guys. I regarded them no differently than I would my children or my brothers.”

“Never shall I fail my comrades.” Those words are part of the creed of the 75th Ranger Regiment, one of the U.S. Army’s most highly trained units, and the one given some of the most dangerous missions. Leroy Petry more than lived up to these words in the heat of battle in a remote village in Afghanistan.

Right before he began his senior year in high school in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Leroy Petry saw that he was headed toward a dead end. Because his parents worked such long hours to support the family—his father as a bus driver and his mother as a clerk at Walmart—he and his four brothers, all physical and competitive, spent a lot of time on their own. Leroy frequently got into fights in high school, trying to establish a reputation with his fists. He was a poor student, skipping school whenever he could. He got Ds and Fs and always raced to the mailbox when he knew his report card was about to arrive so that he’d get it before his parents did.

Realizing that he would soon graduate, Leroy took a look at his life, and he decided he didn’t much like the person he was becoming. “If I want my future to be good,” he realized, “I’ve got to start pushing myself.”

Leroy changed schools to leave his old habits and reputation behind and start with a clean slate. He began studying and working for good grades, surprising himself with what he was able to accomplish when he concentrated. When he graduated, the local chamber of commerce awarded him its Bootstrap Award, given to the student who had worked hardest during the year to pull himself up from failure.

One reason Leroy worked to turn his life around was that he’d dreamed of joining the Army since he was a boy and knew that “the military doesn’t take losers.” Both his grandfathers had fought in World War II, an uncle had served in Vietnam, and a cousin had fought with the Rangers in Operation Desert Storm in 1991. The walls of his home were decorated with photos of these men in their uniforms. His family talked about their military achievements around the dinner table. Leroy wanted people to talk about him someday with the same respect.

In 1999, after trying college for a year to please his parents, Leroy, then twenty, enlisted in the Army. He joined the Rangers, which the Army calls its “premier direct action force,” because he was so impressed with the slogan of this elite unit: Rangers lead the way.

Leroy enjoyed the hands-on activities of basic training, especially the days on the rifle range. He often stayed behind after the other recruits had finished shooting, continuing to practice his marksmanship. One day when he asked for more ammunition, his drill sergeant said to him, “You’re going to be a Ranger, right?” Leroy replied that he was. The sergeant said, “Don’t worry. You’re going to be doing more shooting than you ever wanted to.”

A few months after the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Leroy’s Ranger unit headed for Afghanistan. Images of the smoldering rubble of the Trade Center’s Twin Towers were still fresh in his mind. “It was aimed at innocent civilians just going on with their everyday lives,” Leroy says of the attack. “All these people who didn’t ever find their family members . . . Knowing that we were going after the group that supported this mission was a big factor for me. It wasn’t only revenge. It was a desire to stop this from ever happening again on American soil. If they want to shoot at us when we’re over there, fine. But don’t ever let this happen again to anybody back home.”

Sergeant Leroy Petry on leave with his young son.

Special Mission

On May 26, 2008, Leroy, now a staff sergeant, was in the middle of his first tour in Afghanistan when his platoon was helicoptered to a remote area in the eastern part of the country to try to capture a “high-value target”—a Taliban leader thought to be hiding in a walled compound there. He knew that the mission had to be really important because the Rangers almost never undertook daylight actions. They preferred to operate in the dark, when night-vision goggles and other technology gave them an advantage. He knew that there would probably be a tough fight ahead because Taliban commanders were usually protected by well-armed, battle-hardened security teams.

As they approached the compound, Leroy made a mental map of the adobe-like buildings nestled in a desolate hilly area, noting the places where enemy fighters might be hiding. Almost as soon as they jumped out of their helicopter, the Rangers came under fire. Leroy was moving forward with his platoon leader when he saw another squad entering one of the smaller buildings in the compound. Because that squad’s leader was inexperienced, Leroy yelled that he was going to help. The officer gave him a thumbs-up.

After clearing the building with the squad, Leroy ran toward a chicken coop in the courtyard with another Ranger, Private First Class Lucas Robinson, to make sure enemy forces weren’t hiding there. What happened next remained engraved in his memory: “Out of the corner of my eye I see two Taliban stand up with AK-47s and start spraying from the hip. I was hit in the thigh. It felt like a sledgehammer pounding my leg. I put it out of my mind and kept moving. I saw Robinson get hit just below the left armpit.”

“You Saved Us!”

The two men reached the shed and used it to shield themselves from enemy fire. Robinson had been saved from certain death by the side plate of his body armor. Leroy felt the blood from his leg wound trickling into his boot. He tossed a smoke grenade toward the Taliban as another Ranger, Sergeant Daniel Higgins, ran through the courtyard to support them. All three Americans were knocked down by a grenade, which sprayed them with shrapnel. Leroy had begun firing again when he saw another grenade land a few feet away from Robinson and Higgins. For a moment, time stopped: “I looked at the grenade and I looked at the guys behind me. Those were my guys—guys I was responsible for. I regarded them no differently than I would my children or my brothers.”

Leroy quickly picked the grenade up to throw it around the corner of the shed away from Robinson and Higgins. But as he opened his hand to release it, the grenade exploded. Blood sprayed Leroy’s protective glasses. When he took them off with his left hand, he saw that his right hand had been cleanly severed at the wrist. He studied the wound for a second, looking at the small pieces of shrapnel in the stump and smelling the burning flesh. Then he refocused: He applied a tourniquet from his pack and called his commanding officer to report that three Rangers were down. As an afterthought, he added, “Oh, and my hand is gone.”

Leroy switched his rifle to his left hand and continued firing. Other Rangers arrived to help, but he refused to be evacuated until the enemy fighters outside the shed were killed. Then he allowed himself to be taken to a casualty collection area, where medics worked on his arm. Noticing the blood spilling out of his boots, they cut off his pants and discovered that the bullet that hit him in the thigh had gone through both legs.

As the medics put Leroy on a stretcher and carried him to an evacuation helicopter, the other Americans firing from the rooftops of the buildings in the compound looked down and shouted encouragement. Sergeant Higgins rushed up and put a hand on Leroy’s shoulder, yelling over the deafening noise of gunfire, “You saved us, man! You saved us!”

Leroy Petry greets a young fan, showing him the marvel of his prosthetic hand.

Never Forget

During his nine months of care and rehabilitation at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas, Leroy was fitted with a state-of-the-art artificial arm and hand. He immediately requested a small plaque made of plastic listing the names of the Rangers in his regiment who had been killed and had it bonded to his new prosthetic. “I see it every morning when I put it on and every afternoon when I take it off,” he says. “That way I never lose sight of those who made the ultimate sacrifice.”

Leroy planned to retire from the Army at the end of 2009 when his wounds were fully healed, but the day before he was scheduled to leave he decided to reenlist to work with injured Rangers. He was redeployed to Afghanistan, the only American soldier there serving with a prosthetic arm.

Leroy was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Barack Obama on July 12, 2011. As the president signed his citation, Leroy, noticing that he was left-handed, bent over and whispered, “Mr. President, now I’m left-handed, too. Any tips on how I can keep from smudging my handwriting?”

In 2011 President Barack Obama awarded fellow left-hander Leroy Petry the Medal of Honor “for conspicuous gallantry.”

artificial Limbs: The Gifts of Science and Technology

Leroy’s prosthetic hand can do many of the things a normal limb can do, including clutching a baseball and pledging allegiance.

Because of better body armor and advances in battlefield medicine, fewer soldiers are dying of their wounds than ever before. But that also means that more of them are coming home with very serious injuries—especially lost limbs.

Because of the IEDs (improvised explosive devices) planted along roads and hidden in cities that are the enemy’s weapons of choice, more than seventeen hundred U.S. servicemen and women have lost limbs since the beginning of combat in Afghanistan in 2001. Recovery is physically and psychologically painful, but the chances of living a more normal life with these injuries have greatly improved as a result of advances in prosthetics, artificial arms and legs that function more and more like real limbs.

Artificial legs now mimic a regular walking gait thanks to microchip gyroscopes implanted under the skin.

High-Tech Materials

Prosthetics are being made out of better materials than in the past—lighter, stronger plastics and carbon fiber. At one time artificial hands were merely hooks; now sensors the size of a grain of rice implanted in the patient’s arm can detect nerve signals from undamaged muscles that allow a prosthetic hand to open and close and rotate 180 degrees. Artificial legs that once had to be “swung” from one step to another with difficulty now walk gracefully as a result of microchip gyroscopes implanted under the skin. Some amputees now have different artificial legs for different activities: cycling, hiking, dancing, martial arts, and ice-skating.

But while advances in prosthetics have meant a better quality of life for wounded servicemen and women, they don’t answer the question many of these patients anxiously ask themselves when they return to civilian life: What will people see when they look at me?

Corporal Jason L. Dunham covered a grenade that was about to explode, putting his comrades before his own safety. A mother writes about what is left behind when a marine doesn’t come home.

The Loss of a Son

by Deb Dunham

Deb Dunham hugs her oldest son, Jason, in an undated photograph,

“Medal of Honor Recipient Corporal Jason L. Dunham, United States Marine Corps, 2007, deceased.” This is how history records the memory of this warrior and what people read when searching for information about this decorated marine. To us, our son represented so much more.

April 14, 2004, was the middle of school spring break and the Easter holiday for us in Scio, in the southern tier of New York State. My husband, Dan, was in bed, as were our two youngest children, Katie, eleven, and Kyle, fifteen. I was in the living room reading a novel, enjoying the few moments of peace and quiet every working mother craves.

The phone rang at 11:45 p.m. When the phone rings at that hour of the night, the sound is shrill and distinct; every nerve in your body jumps, and your gut hits the floor. Whoever is on the other end of the line probably does not have good news. I did a quick inventory: Katie and Kyle were asleep in their rooms; Justin, twenty-one, was living and working in Butler, Pennsylvania, just north of Pittsburgh, about three hours away; and Jason, twenty-two, our oldest son, was a marine deployed in Iraq. Instead of just picking up the phone, as I normally would have done, I found myself near the doorway of our bedroom calling my husband’s name. He told me to answer.

On the other end of the line was a man calling from the marine base in Twentynine Palms, California. He said that Jason had been injured and was in critical condition. The information we received was brief and concise in the military way. It left us with countless questions and the dread that the worst could yet happen. But the phone call was and still is a blessing compared to a knock on the door, which is how the military normally contacts the family about a killed-in-combat death. We had the comfort of knowing that Jason was still alive.

Before he went overseas, or was deployed, several months earlier, Jason had spent his leave with us over the Christmas holiday. One evening during that visit, Dan and I sat curled together on the couch while all the kids were horsing around in one of the back bedrooms. Dan wanted to know how I felt about Jason being deployed. I told him I did not feel good about it. From his childhood, Jason had always looked out for the underdog. He had grown into a six-foot-one man, all muscle, and he could handle himself. Most of the time, when called on to settle a dispute, he would turn up the charm and was able to talk the situation toward an amicable result. But if called on to resolve something physically, he never hesitated. I knew that if something went wrong, Jason would be in the middle trying to protect those who needed help—and this was what made me uneasy.

That was exactly what had happened. Jason was serving as the squad leader of a marine platoon near the town of Al Karabilah, about seventy miles south of Baghdad, in Iraq. On the day we were told, he and his men had been called in because insurgents had attacked the battalion commander’s convoy. Traffic was snarled, so they got out of their Humvee and began to search all vehicles for weapons. When they came to a white Land Rover, Jason ordered the driver to get out; instead, the driver jumped out of the vehicle, reaching for Jason’s throat. Jason grabbed him, wrestling him to the ground, but the insurgent managed to drop a live grenade. Without hesitation, Jason covered the grenade with his helmet and body to shield his friends. It exploded, and some of the shrapnel lodged in his brain.

Jason was in a coma and not expected to recover when he was flown home to Bethesda Naval Hospital in Maryland. There, we were able to spend a brief but precious time with him. Dan sat on one side of his bed holding one of his hands; I sat on the other side holding his other. We linked our free hands over the bed. Medical staff, marines, and sailors, all there to honor a fellow warrior, filled the room. As Dan and I sat watching our child leave us, our hearts broke, never to mend in our lifetimes.

As excruciating as that moment was to live through, it was a second blessing that both Dan and I cherish to this day. We understand the gift that we had been given—having this brief time with Jason before he left us for his next journey. We had a chance to say good-bye.

Within three to four months’ time, we learned that Jason had been nominated for the Medal of Honor by the men he had served with. Dan had been in the Air Force and understood immediately what this honor meant. It took me a little longer. When you lose a child, you never “get over it.” You find a “new normal,” getting up each day to do the best you can.

Jason Dunham, shown here in Iraq, was a twenty-two-year-old corporal when he covered an insurgent’s grenade to save the lives of three other marines, an action for which he lost his life.

When we finally learned that Jason was actually going to receive the Medal of Honor, we felt a host of emotions all at once: pride that our nation recognized the qualities we had always seen in our son as he grew up and that it was now validating his heroic act of selflessness with its highest award for valor; sadness that Jason was not here to accept this prestigious honor himself; and awkwardness in that people were congratulating us for his achievement. We hold fast to the fact Jason did the right thing. He probably would have been embarrassed by all the praise he received for doing what he would have perceived as his duty in saving the lives of his men.

The ceremonies that followed were a whirlwind—from the medal ceremony at the White House, to the induction into the Hall of Heroes in the Pentagon, to all the meetings with people who were incredibly kind to us. By the time we attended the closing ceremonies at the Marine Corps museum, it was all a blur. Since that day we have fielded thousands of invitations to attend military and civic events that want to honor Jason. We have learned to sort out the most important events to attend. But whenever possible, we try to honor Jason by helping others remember that our military, his brothers, continue to fight for and guard our freedoms.

Jason was the kid I constantly had to remind to take out the garbage, the one whose name I had to write in his clothes because he would leave them at his friends’ homes. This is the son who would stop by my classroom to see how I was and if I had any extra food. This is the kid who, on leave, would gather up his three younger siblings from their classes, take them to lunch in the cafeteria, and charge “his” lunch to my account, knowing that it would be covered since I work in the same pre-K to 12 building my children attended. This is the boy who had no problem yelling down the hall in front of his friends, “Yo, Mama, I love you.” I am so proud that he became part of a group that strives to protect and care for those who are not able to fend for themselves.

Every day, we feel a part of our hearts and lives are missing. The comfort in our loss is knowing that Jason chose to do the right thing. Three men are alive today because he acted boldly in the space of an instant to cover a grenade that might have killed them. They all have families today because of his actions. And who knows, God may have a plan that one of them or one of their children will do something great that benefits humanity, something that would not have been possible without Jason’s courage.

Jason received the Medal of Honor for going above and beyond. For his father and me, he was merely doing something that day in Iraq that he had done in all the years that he was with us. What he did was who he was. We miss him dearly.

President George W. Bush presents Deb Dunham with the Medal of Honor awarded posthumously to her son Jason. To Deb’s right is her husband, Dan. Partially hidden are their three children (from left), Kyle, Justin, and Katie.

A Daughter’s Story

A Daughter’s Story