How Wrestling Got a Hold on My Uncle and the Nation

On the evening of Friday, November 22, 1963, Monsignor Louis Meyer of Epiphany of Our Lord Parish, director of the youth department for the Archdiocese of St. Louis, read a prayer in memory of President John F. Kennedy, who had died less than eight hours earlier in Dallas from an assassin’s bullets.

The 7,200 people filling two-thirds of the seats at Kiel Auditorium stood in respectful silence as the priest eulogized their martyred leader. When Monsignor Meyer was finished, everyone turned toward the American flag onstage while the U.S. Army Band Chorus recording of the national anthem blared tinnily over the public-address system. Then the crowd settled in for a night of professional wrestling, climaxed by National Wrestling Alliance heavyweight champion Lou Thesz’s title defense against the evil German, Fritz Von Erich.

Two days later, the commissioner of the National Football League, Pete Rozelle, would be excoriated for ordering NFL teams to play their full slate of games while the nation was still reeling from the death of the president. Yet in St. Louis there was no particular outcry when the NWA’S show went forward. If anything, the promoter won sympathy for his predicament — after all, most of the wrestlers had already arrived in town before news of the assassination — and praise for his ingenuity in arranging a prayerful preamble to the ritual of mayhem performed by assorted eccentric, underdressed circus athletes.

Why?

I believe I know some of the answers to that question — in part because I myself, at age nine, was in attendance at Kiel Auditorium that night. Also because the St. Louis promoter was my late uncle, Sam Muchnick.

A jagged line running from Sam Muchnick, the principal owner of the St. Louis Wrestling Club, to Vincent Kennedy McMahon, the flamboyant chairman of World Wrestling Entertainment, tells a good slice of what might be called the backstory of twentieth century popular culture.

McMahon turned wrestling into more than just a compelling metaphor for the mountebank inside all of us. For better or worse, the WWE is a powerful fact on the ground of our national life — providing the theme for a Times Square entertainment complex, churning out bestselling autobiographies, underpinning a huge public stock offering, helping elect a governor and manufacture one of the movie industry’s hottest action stars, and cheerfully exporting teen-male misogyny from cable fringe to network prime time.

American sports and society had an appointment with McMahon’s XFL football on NBC on Saturday nights in 2001. That that experiment would go down as one of the most spectacular failures in television history shouldn’t obscure the meaning of its having happened at all. The XFL was an all-too-glibly dismissed footprint of the mainstreaming of antisocial values. With or without the XFL, Vince McMahon became a showbiz baron, a Forbes 400 billionaire, and like his Connecticut forebear P.T. Barnum, an A-list exhibit to H.L. Mencken’s contention that no one ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the masses.

In the World According to Vince — that meta-reality with unassailable traction — the XFL story contained no moral, unless it was that his brilliance in one field didn’t necessarily translate into another. In truth, this was a lesson he’d learned well before he owned wrestling — as far back as 1974, when his promotion of a continent-wide live closed-circuit telecast of an Evel Knievel stunt event flopped worse than Knievel’s motorcycle sinking safely attached to a parachute down into Idaho’s Snake River Canyon gorge.

And it was a lesson McMahon saw reinforced at least three other times after he had become master of the wrestling universe — when his company, feeling its oats, made failed forays into the movie business, boxing, and bodybuilding. (One area’s genius, it seems, is another’s “mark.”) Asked by television interviewer Bob Costas, in the midst of the XFL debacle, what he would do if his dream of a football league died hard, as it would swiftly proceed to do, McMahon replied defiantly, and with a lack of sentimentality that you had to admire at some level. “I’ll get up off my kiester and try something else,” he snarled.

My Uncle Sam, too, was quite successful, on his own scale and his own terms. He preferred operating in the shadows instead of in the spotlight. For him, respectability was something to be finessed and molded, rather than just turned on its head and overwhelmed by capital, so he guarded exposure as zealously as McMahon would court it.

But in the final analysis, and like it or not, the two men of two generations were bonded by the gimmickry of their product, by their slippery quest for legitimacy, and by the even more disturbing sense that their authenticity revealed our dishonesty, rather than the other way around. Verisimilitude, not truth, was the coin of their realm.

Larry Matysik interviews Bruiser Brody

Like the early moguls of Hollywood — Louis B. Mayer, Jack Warner, Samuel Goldwyn — some of the impresarios most responsible for transforming wrestling from country carnival sideshow to urban arena spectacle happened to be Jews from Eastern Europe. Sam Muchnick was born in the Ukraine in 1905. Another wrestling promoter with roots in the Pale of Settlement was Jack Pfefer, a Russian whose thick Yiddish accent and stereotypical money manipulations were the stuff of legend — reviled legend.

Sam’s model was different, smoother, more assimilated. I always thought of Sammy Glick, the fast-talking deal-maker of Budd Shulberg’s novel What Makes Sammy Run?, though the Sammy I knew exuded less hyperkinetic insecurity and more sedentary mystique. My father’s father was a man of religion who had a hard time holding down a job in America because he refused to work on the Sabbath. Uncle Sam, like Sammy Glick, would have none of that, and quickly jettisoned religion, accent, and other old-world baggage.

But unlike Jack Pfefer, or for that matter, just about any wrestling promoter of any era or ethnicity, Sam was known to be scrupulously, almost fetishistically, honest in his business dealings. His last aide de camp, Larry Matysik, had a strict routine after every show, which involved breaking down 32 percent of the house gate receipts into cash envelopes, scaled from the main-eventers (who shared a full half of the 32 percent) on down to the “job boy” in the first preliminary match. Often the distribution was completed before the wrestlers had finished showering. In 1953 an electricians’ union strike forced the late cancellation of a St. Louis wrestling show. Sam gathered the talent and explained what had happened before proceeding to pay each man a generous estimate of what might have been his share of the house that never was. The wrestlers, led by a guy named Hans Schmidt, caucused, and Schmidt soon returned, handing every dime back to Sam.

“We decided we don’t even want trans,” Schmidt said. “You’ve always treated us fair and square, and the electricians’ strike isn’t your fault.” Fortunately for Hans Schmidt’s reputation as a German heel, this anecdote didn’t leak to the public.

Upon graduation from Central High School in St. Louis, Sam helped support his immigrant family with a job at the post office. In 1926 he got his first big break, joining the sports department of the St. Louis Times. Sam lacked the writing polish of his Cardinals baseball beat colleague, Notre Dame-educated Walter W. (Red) Smith of the St. Louis Star, later a Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist in New York. But in a time of Prohibition and of baseball idol Babe Ruth’s discreetly unreported debaucheries, no journalist could schmooze better or hold secrets closer than the man known affectionately as “Thammy” (a reference to his signature lisp). Along the way, Sam befriended Jack Dempsey, Mae West, and Al Capone. Among the guys and dolls, Sam Muchnick was a guy’s guy. His crowd specialized in practical jokes that in the abstract were funny, but in the retelling sound creepily sadistic — such as the time he lent his car to his best friend, wrestler Ray Steele, and then arranged to have Steele thrown in the pokey overnight for stealing it.

A facility at these kinds of head games would come in handy after the Times went under in 1932 and Sam landed as the publicist and right-hand man for Tom Packs, a St. Louis-based circus entrepreneur who was also one of a handful of promoters running the nascent national pro-wrestling “syndicate.” Eventually the two had a falling out and Sam started his own promotion.

The golden age of wrestling, coinciding with the advent of television and the formation of a consortium of promoters called the National Wrestling Alliance, followed Sam’s service during World War II in the Panama Canal Zone. An Army buddy, Mel Price, also a former sportswriter, who had been elected to Congress from the East St. Louis, Illinois, district, proved an invaluable ally when the NWA, your basic cartel, got investigated by the Justice Department.

Promoter potentates at a National Wrestling Alliance convention

Price — who would go on to become the longtime chairman of the House Armed Services Committee — helped negotiate a consent decree whereby the NWA continued to operate despite few if any changes to its anti-competitive practices.

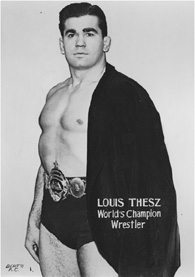

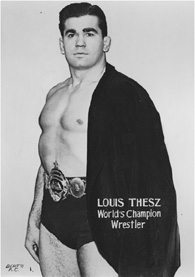

The wrestling nation was thus safely divided into Mafia-like fiefdoms, with each promoter running things pretty much his own way. The only unifying principle was the touring NWA champion, who through much of that period was another St. Louis product, Lou Thesz, the son of a Hungarian shoemaker. (When Thesz died in 2002, his obituary made The New York Times.) Sam Muchnick was a founder of the NWA and, with only a couple of brief interregnums, the organization’s president for a quarter of a century.

Vince McMahon’s WWE sells real theater. Sam Muchnick’s NWA sold fake sport. While there’s no accounting for taste, aficionados swear that this is a distinction with a difference.

But let’s dispense with the sentimental notion that what McMahon corrupted was anything other than a conceit, with the emphasis on the “con.” Pro wrestling has been fixed since the earliest days of Strangler Lewis, Farmer Burns, and Frank Gotch, and for the simplest possible reason: While the amateur version of the sport appeals to something primal in us, it achieves critical market mass only when wed to a storyline. Wrestlers used to weave their narrative strictly between the ropes via a lowbrow performance art known as “working.” The “spots,” whether high-wire maneuvers like flying dropkicks, or pulled punches or more basic mat moves, were communicated by whispers and body language. If a worker got out of line and attempted a “double-cross,” his opponent was expected to “shoot” or “hook” to bring about the intended result. (However, such a breach of etiquette was rare.) Up and down the “rasslers” would go, suspending the breath, emotions, and disbelief of the spectators of a slower-paced era.

McMahon merely took wrestling apocrypha to a heady new level, much the way Michael Milken shook the financial world with the invention of junk bonds. The fact that there are now re-takes of botched interviews before live audiences who are instantly let in on the joke is essentially an esthetic evolution. McMahon is a postmodernist whose historical role, more than anything else, is to put pretense in its place, for fans and non-fans alike. As he has proven, the carny code of “kayfabe” — whereby even the most sophisticated observers might not catch on to the broad outlines of the charade — was more about the psychological needs of the workers than about the business fallout of disillusioning the “marks.”

Still, one conclusion is inescapable. Wrestlers from the old school, who had their hands full with their campy struggle to maintain credibility before camp was cool, took care of each other in the ring. They suffered from ordinary sports injuries and cauliflower ears, but they also by and large led long and productive, if somewhat crusty and Runyonesque, lives. A few even had crossover careers — and I’m not just talking about Gorgeous George. Check out Mike Mazurki in the 1949 Richard

New Jack: as hard-core as it gets

Widmark–Gene Tierney noir classic Night and the City, one of Mazurki’s numerous character roles in the forties and fifties. Contemporary wrestlers might snicker at the hokum, but their ironic distance from the art of the work exacts a considerable physical and psychic cost. As the tortured comparisons to the Greco-Roman tradition have declined, so the ante for hard-core realism has been upped. Today, wrestlers bash each other over the head with chairs or ram each other into cars offstage, crash onto thumbtacks from ladders or steel cages, pump themselves with steroids and human growth hormone, snort cocaine, pop uppers and downers, and, not incidentally, drop dead before their time in alarming numbers. As my friend Phil Mushnick of the New York Post once wrote, you won’t find a lot of Old Timers’ Days in pro wrestling.

Vince McMahon’s special genius as a businessman is his ability to generate multiple revenue streams; on the financial news circuit, his wife and CEO Linda McMahon assures New York Stock Exchange investors that the company is always looking for “new ways to monetize our resources.” The XFL was just one of the more audacious examples. Sam Muchnick helped promote the last world heavyweight championship boxing match in St. Louis — Joe Louis vs. Tony Musto, 1941 — and in later years served as the Harlem Globetrotters’ local sub-agent; but his business was maximizing fannies in the seats at twice-monthly wrestling shows, period. Even his folio newsletter, mailed to subscribers and hawked at the arena, was at best a break-even proposition.

St. Louis Wrestling Club events were promoted via Wrestling at the Chase on KPLR-TV, Channel 11, whose first announcer was Joe Garagiola (before he left to become host of the NBC Today show) and whose original venue was the ornately chandeliered Khorassan Room of the exclusive Chase-Park Plaza Hotel. Businessmen in suits and their wives in evening dresses tried not to spill wine on the tablecloths while they watched Dick the Bruiser use his Atomic Drop on Pat O’Connor. The formula was tight and, by wrestling standards, dignified: perhaps one Texas Death Match per year, a couple of masked men per decade, a finish involving a referee “bump” once in a blue moon. German and Japanese bad guys marked the xenophobic limit. Extracurricular TV skits, known as “angles,” were eschewed. “Juice,” or blood, was virtually nonexistent. Somewhere in the course of the season Sam would mix in a midget tag match and a women’s special attraction.

Vince McMahon picks gleefully at race-baiting or any other market-tested social scab (recently the latent tension between wrestling’s homophobia and homoeroticism has become explicit). Sam Muchnick’s racism was more genteel, but of course it also had the effect of stifling opportunity. St. Louis remained a de facto Jim Crow town long after the 1954 Supreme Court decision, and Sam knew nothing if not how to get along. In the mid-sixties he finally brought in his first black wrestler, football star Ernie (The Cat) Ladd, and the African Americans from the North Side popped huge for him. Perhaps unsettled by the possibilities, Sam kept Ladd buried in the undercards. (Ladd would go on to become one of the highest-profile black supporters of the presidential candidacy of George W. Bush.) It would be several more years before a black wrestler actually got a championship shot in St. Louis — and that would be a far inferior performer, Rufus R. Jones, whose hard head and soft belly conformed to the conventional view of a black male cartoon character.

Ernie “The Cat” Ladd administers his trademark thumb to the throat

There are other instructive contrasts between McMahon and Muchnick — notably the way the former places himself at the center of his on-camera cast, and even pushes his son Shane and daughter Stephanie into television stardom. Like the Godfather, Sam Muchnick preferred to shield his family.

His was a modest milieu bounded by sports-world cronies and local cops and pols. He spread a few nickels around, making sure that the state athletic commission was stocked with friendly faces and that the Friday night match results ran in the Saturday morning St. Louis Globe-Democrat (but little more — the best PR can be the kind that keeps your name out of the newspapers).

Sam Muchnick’s St. Louis farewell — January 1, 1982: with Gene Kiniski, Joe Garagiola and Larry Matysik

Through such minimalism he cultivated a nice-guy image. Few doubted, however, that someone could survive so long in such a seedy business without a certain knack for intimidation. An otherwise unremarkable dresser, Sam always sported a sinister black homburg which, St. Louis Post-Dispatch sports editor Bob Broeg liked to joke, gave him “the appearance of a member of the Soviet secret police.”

Sam’s last show was on New Year’s Day 1982. Later the same year, Vince bought Capital Wrestling Corporation, the company controlling the Northeast territory, which was owned by his father, Vincent J. McMahon, and his partners Gorilla Monsoon, Phil Zacko, and Arnold Skaaland. In 1963 the senior McMahon’s group, which then included Toots Mondt and Willie Gilzenberg, had broken off from Sam’s National Wrestling Alliance, started something called the World Wide Wrestling Federation, and crowned its own New York–based “world champion,” Bruno Sammartino. But by the seventies there was again peace between the NWA and the folks of what had now been shortened to the World Wrestling Federation (WWF). On the East Coast they were even allowed to continue billing their guy as the champion. Wrestling promoters are smart enough to know that title changes are like election results: if they’re not reported on TV they never happened.

But now it was a new world, a world of cable and deregulation, of snarky young promoters and multimedia marketing. Even junk culture had become something to be branded instead of closeted. Old-style wrestling was dead. The king was a high-low concept called “sports entertainment,” and Vince McMahon was its pioneer and foremost practitioner. Simultaneously and magically, sports entertainment moves the carnival into the mainstream, infects the latter with the values of the former, and packages the merchandise to prove it.

Capital investment had been transformed since the night Lou Thesz escaped Fritz Von Erich’s Iron Claw hours after the Kennedy assassination. So had the human stakes. In October 1997, WWF wrestler Brian Pillman was found dead in Minnesota of a heart attack — almost certainly brought on by his use of steroids, human growth hormone, and painkillers — just hours before the start of the Badd Blood pay-per-view from the new Kiel Center in St. Louis. Pillman had been scheduled for matches on the show against Dude Love and Goldust. McMahon taped a cut-in explaining the circumstances and ordered the show to go on. The next night, McMahon ran a tribute to Pillman, which included an appearance by his tearful widow, on Raw, the flagship USA cable network wrestling show.

In May 1999, WWF wrestler Owen Hart was killed when a high-wire stunt went awry shortly after the start of the Over the Edge pay-per-view from the Kemper Arena in Kansas City. McMahon ordered the show to go on. The next night he turned Raw into a tribute to Hart. That night’s edition of Raw emanated from the Kiel Center in St. Louis.

In between, on December 30, 1998, Sam Muchnick died at age ninety-three. The funeral was held three days later at the chapel of Memorial Park Cemetery in suburban St. Louis. Probably the only figure in attendance even remotely recognizable to contemporary wrestling fans was the legendary former NWA champion, 81-year-old Lou Thesz, who arrived late after cracking up his car while driving straight through on ice-slick roads from his home in Virginia. Sitting alongside my father, my sister, and my cousins, I could make out people like Moose Mueller, the off-duty cop who used to moonlight as a Wrestling at the Chase security guard. I felt like I was trapped on the set of the Woody Allen movie Broadway Danny Rose.

On Sam’s instructions the funeral was co-officiated by a rabbi and Monsignor Meyer. In his eulogy, the priest tenderly remembered the evening thirty-five years earlier when he was summoned to deliver a prayer before wrestling fans grieving for their assassinated president. He remarked on how classy it all was.

“Who besides Sam Muchnick,” Monsignor Meyer asked rhetorically, “would have thought of something like that?”

OK, enough Muchnick family history. On with the show. As both Sam and Vince would have agreed, it’s the American way.

On with the show