Hulkster Vitamins Come in Two Forms — Orals and Injectables

People, March 23, 1992

He is pro wrestling’s first million-dollar man: a crossover star of pay-per-view, silver screen, and Madison Avenue whose glistening six-foot-six-inch, 290-pound physique, intense glare, thinning blond mane, and friendly growl have been used to endorse everything from an antiperspirant stick to kids’ vitamins.

But now — wham! thud! oof! — several of Hulk Hogan’s former ring cronies have delivered what, in wrestling terms, amounts to an off-the-turnbuckle clothesline: they claim Hulk, thirty-eight, bulked up for years on muscle-inflating steroids and abused other drugs.

Hogan has declined People’s repeated requests for an interview to address these charges, which threaten not only his good-guy image, but his King Kong–size earnings as well. (The three-time World Wrestling Federation champion grosses an estimated $5 million a year, much of it coming from such outside-the-arena enterprises as commercials, toys, and movies.)

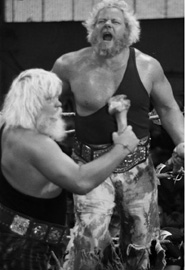

“Superstar” Billy Graham strikes a pose

Hogan’s headlock on the public’s affections actually began slipping last June, when Dr. George Zahorian III, the attending physician for pro wrestling bouts in south central Pennsylvania, was convicted under a 1988 federal law that outlaws the distribution of steroids for non-therapeutic purposes. Among the steroid abusers Zahorian named during his testimony was Hogan. Federal Express records produced by government officials show Zahorian sent packages to several dozen wrestlers, including Hogan. Four of them testified that the packages they received contained steroids.

Despite the testimony, Hogan’s lawyers managed to quash a subpoena for him to appear at Zahorian’s trial, arguing that it would have invaded their client’s privacy and threatened his livelihood. After the trial Hogan denied all, telling talk show host Arsenio Hall, “I am not a steroid abuser.” He did admit to injecting steroids briefly in 1983 while under a physician’s care for a torn bicep. Hogan gave the same account to People last October, but added, “It’s like putting poison in your body.”

Among Hogan’s fellow grunt-and-groaners, his public denials of steroid abuse were a stretch even by wrestling’s elastic standards. In January, two of his ex-colleagues, Superstar Billy Graham (real name: Eldridge Wayne Coleman), forty-eight, and David Shults, forty-two, whose wrestling moniker was Dr. D, began making the TV tabloid and radio talk show rounds. While admitting to being ex-steroid users themselves, they claim Hogan also had more than a passing acquaintance with the synthetic hormone.

Graham, a former WWF champ, remembered when Hogan, using his real name, Terry Bollea, was playing bass in a rock band in 1976 and trying, without success, to climb into the ring. At 230 pounds he was big — but not big enough. He befriended Graham and began asking about steroids. “I saw him a year or two later, and he’d gained at least eighty to ninety pounds,” said Graham, who claims Hogan spoke of tennis ball-size scar tissue on his hips, the result of repeated steroid injections.

“I injected him well over 100 times,” says Shults, now a New Haven, Connecticut–based bounty hunter for bail bondsmen, who maintains he was introduced to steroids in the late seventies by Hogan, then billed as Terry “The Hulk” Boulder. In exchange Shults would offer the rookie tips on such things as how to project his ring persona believably in public, while helping him take the drug, which is injected directly into whatever muscles require enlargement.

“I regularly gave him shots in the triceps [back of the arms], where he couldn’t reach himself, and also a few times in the butt,” says the former Dr. D. “Sometimes he took 12 cc’s three times a week.”

“Hulk always bragged about steroids,” says Joe Bednarski, who retired from his WWF career as Ivan Putski, the Polish Power, in 1986. “He’d say, ‘Shit, I don’t cycle [a practice in which users abstain for a while to let the body return to its normal state]. I don’t get off of them. That’s how I stay “over” [popular].’”

But his sympathizers think Hulk is being unfairly worked over for using a drug that, until recently, could be legally obtained by anyone.

“Who didn’t do steroids?” says Ken Patera, a former wrestling superstar and 1972 Olympic weightlifter. “The word came down from the promoters, especially [WWF owner Vince] McMahon, that you had to be bigger than life. The only way to do that was to take anabolic steroids.”

Moondog Spot and Randy Culley, Moondog Rex

McMahon, a bodybuilder who has acknowledged experimenting with the anabolic steroid Deca-Durabolin, retorts, “I’ve never encouraged anyone at any time to take steroids.”

But Hogan’s drug abuse went beyond steroids, according to David Shults. He says Hogan also used cocaine, marijuana, uppers, and downers. Shults’s friend Randy Culley, who wrestled under the names The Assassin and Moondog Rex, confirms: “Me and Hogan ran around together. He was real bold about steroid use. And he also did Placidyl [a sleeping capsule], Quaaludes, cocaine.” (So, reportedly, did a lot of others: at least five pro wrestlers have died of drug overdoses in the last decade.)

Billy Jack Haynes, a WWF performer from 1986 to 1988, recalls a harrowing car trip to Hogan’s Connecticut home with Hulk and two other wrestlers after a bout at Madison Square Garden in 1987. “There was pot, alcohol, pill-popping. Hulk was going 70 miles per hour on the freeway, stoned out of his gourd,” says Haynes. “I got mad at him for driving under the influence. We almost had a fight over it.”

The New York Times, Sunday Sports, July 7, 1991

With the recent conviction on drug-trafficking charges of Dr. George T. Zahorian III, the physician who supplied anabolic steroids to Hulk Hogan and other professional wrestling stars, the final stage in the life cycle of one of the signature pop-culture phenomena of our times has begun.

Wrestling, which emerged overnight from the carnival fringe to the show business mainstream, may be about to crawl back into the hole from whence it came.

Zahorian was found guilty by a jury in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in the first test case of a 1988 federal law that made illegal the distribution of steroids for non-therapeutic purposes. Steroids, which helped turned wrestlers like Hogan from pseudo-athletes into freakishly muscular cartoon action figures, fueled the estimated $150 million kiddie merchandising empire of Vince McMahon, the owner of the World Wrestling Federation.

Now McMahon (who was, according to court testimony in Harrisburg by Zahorian, one of the people who used drugs pushed by the doctor) is striving to preserve the image of whole-some family entertainment he so ingeniously cultivated over the last seven years.

In its Barnumesque excess and its relationship to larger currents in business, government, and society, McMahon’s rise has been prototypically American. The dull truth, cleverly concealed from his patrons in the East Coast media, was that wrestling actually peaked as a live-event spectacle in 1983 — this renaissance spearheaded by old-line promoters in Atlanta, Minneapolis, Charlotte, Dallas, and Tulsa, before McMahon was a major player.

But McMahon was the first to realize the potential of cable television to break the sport’s traditional territorial fiefdoms and make possible a truly national marketing base. By 1985 the WWF was on NBC and CBS; by 1987 it was filling the 90,000-seat Silverdome in suburban Detroit and pulling in record pay-per-view numbers for a grudge match between Hogan and Andre the Giant. Competitors like Ted Turner, the cable mogul who owns World Championship Wrestling, a much weaker rival group, continued to stalk McMahon, but he remained the master of kitsch and mock violence, with an ear for the campy underside of the Reagan-Rambo 1980s.

Around 1989, however, the wrestling economy soured. Over-exposure caused attendance to plummet, and the public was no longer as amused by McMahon’s propensity for tasteless shtick. Earlier this year, WrestleMania, the WWF’S biggest spectacular, had to be moved from the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum to the much smaller Los Angeles Sports Arena, in part because of negative reaction to the way the Hogan-Sergeant Slaughter “feud” exploited the Persian Gulf war.

Pay-per-view buy rates — the percentage of homes that were purchasing the shows — were down as well, according to Dave Meltzer, publisher of the Wrestling Observer, although the universe of wired homes continued to grow. And cable operators were having better luck with other kinds of events, notably boxing matches.

As with the original wrestling resurgence in the late 1940s, the sport’s larger historical role seemed to be to provide cheap, easy programming for a new medium, popularizing it for the delivery of more respectable forms of entertainment.

Like Elvis, McMahon was living off the residuals, as his parent company TitanSports generated more revenue from the licensing of dolls, video games, T-shirts, and ice cream bars than it did from the sale of tickets. He built a $9 million office complex in Stamford, Connecticut, to house a sparkling new television studio and post-production facility, but soon reached a dead end with what wrestling alone could deliver. Ever desperate for new product lines, he made unsuccessful forays into movie production and boxing promotion, and most recently started a professional bodybuilding circuit.

If indeed the Zahorian scandal finally puts the wrestling resurgence down for the count, the footprints the sport left were remarkable. More or less serious public affairs programming like The McLaughlin Group, a political talk show with John McLaughlin as host, owe their stentorian style of discourse to wrestling interview technique.

With regard to steroids, they can be found in legitimate sports, too, as Brian Bosworth, Ben Johnson, and Lyle Alzado have demonstrated. Bodybuilding, a junk sport in which steroid abuse is even more pervasive than in wrestling, produced Arnold Schwarzenegger — an even bigger celebrity than Hulk Hogan — whose appointment as chairman of the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports seems to be a classic case of the fox guarding the chicken coop.

Like Vince McMahon, they’re all part of a world where appearance and hype are the undisputed tag-team champions. There’s something comforting, and something disturbing, about the process by which wrestling manifests our worst instincts, then implodes and allows us to go guiltlessly about our lives. In the end, intelligent observers are threatened not by what’s fake about it, but by what’s real.

“Hogan isn’t a bad guy,” says Dave Meltzer, publisher of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter. “He works tirelessly for charities, [even] when the cameras aren’t around.” But by failing to fess up to past steroid use, Meltzer believes, “he revealed himself to be just another carny con man.”

It’s an image of Hogan sharply at odds with that of the loving family man (he and his wife Linda, thirty-two, have a daughter, Brooke, four, and son, Nicholas, two) whose name is licensed to sell a popular brand of kids’ vitamins. As a result of the steroids scandal, the joke heard in hard-core bodybuilding gyms these days is: “Hulk Hogan Vitamins come in two forms — orals and injectables.”

Yet Solaris Marketing Group president Barry Ross, whose company distributes the vitamins, rejects any slurs on Hulk’s good name, adding, “We stand by him 100 percent.” Although a spokesman for Hasbro (which offers a line of Hulk action toys) would not return People’s phone calls, the scent of scandal has not persuaded Gillette to cancel Hulk’s Right Guard deodorant spots.

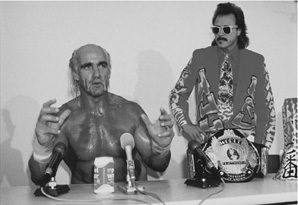

Hulk Hogan with Jimmy “The Mouth of the South” Hart

Still, the accusations of drug abuse may have already accomplished what WWF opponents Sergeant Slaughter and Andre the Giant could never do: toss the Hulkster out of the ring — permanently. As if sensing his superstar’s career is kaput, McMahon is pumping up Hogan’s WrestleMania VIII bout against Sid Justice in the Indianapolis Hoosier Dome on April 5 as Hulk’s last match before a “hiatus” that McMahon says “could be six months or six years, or forever, I don’t know.”

It is doubtful, though, that any such hiatus will be the end of Hulk’s career. He has a standing offer to wrestle in Japan, where he can take home a six-figure payout for just a few bouts (and where steroid use by wrestlers is relatively uncommon). Still, the price of any such banishment will be felt not so much by the Big Guy as by the little guys — the legions of Hulkamaniacs not yet ten years old.

Sayonara, Hulk? Say it ain’t so.

Randy “Macho Man” Savage and Jake “The Snake” Roberts